"Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends

in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand"

CORAL REEFS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

UNEP/GEF

Regional Working Group on Coral Reefs

First published in Bangkok, Thailand in 2004 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

Copyright © 2004, United Nations Environment Programme

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without

special permiss ion from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate

receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.

No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose without prior permission in writing

from the United Nations Environment Programme.

UNEP/GEF Project Co-ordinating Unit, United Nations Environment Programme,

UN Building, 9th Floor Block A, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand.

Tel.

+66 2 288 1886

Fax.

+66 2 288 1094

http://www.unepscs.org

DISCLAIMER:

The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of UNEP or the GEF. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP, of the GEF,

or of any cooperating organisation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, of its authorities, or of

the delineation of its territories or boundaries.

Cover Photo:

Coral Reefs in Ambon, Indonesia - Dr. John W. McManus.

Photo credits:

Page 5

Hill cutting and construction activities degraded the coral reefs near this site - Ridzwan Abdul Rahman

Page 6

Bomb fishing - George Woodman

Page 7

Inexperienced divers descending to a coral reef - Yihang Jiang

Authors:

Dr. Chou Loke Ming, Dr. Ridzwan Abdul Rahman, Mr. Kim Sour, Dr. Suharsono, Mr. Abdul Khalil bin Abdul Karim,

Dr. Porfirio M. Aliño, Dr. Thamasak Yeemin, Dr. Vo Si Tuan, and Mr. Yihang Jiang.

For citation purposes this document may be cited as:

UNEP. 2004. Coral Reefs in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 2.

CORAL REEFS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

1

FOREWORD

The rich biodiversity makes the reefs here valuable in

Covering three million square kilometres of sea surface,

terms of ecotourism and in the potential for natural

the South China Sea forms a major large marine

bioactive compounds. The great variety of reef species

ecosystem bordered by nine coastal states. Located

provides a great source for research into natural

within the global centre of marine biodiversity, the

product chemistry. Novel bioactive compounds with

South China Sea supports immensely rich species

biomedical and agricultural applications can generate

diversity. Coastlines of the states bordering the sea are

huge economic benefits. The high degree of endemism

liberally endowed with coral reefs, a unique and

makes it imperative to maintain this resource.

certainly the most colourful of all marine ecosystems. In

the deeper part of the South China Sea, numerous

While the economic benefits of coral reefs are known,

island groups also support coral reefs. Fringing reefs

little is done to protect this ecosystem. Again, there are

and atolls occur throughout this marine basin forming

numerous reports pointing to reef degradation and

an effective network for larval connectivity and

destruction in the South China Sea. The ecosystem

migratory species.

deserves better protec tion so that its full economic

value can be realized. Coastal development and

The reef ecosystem is known to provide ecological

economic expansion together with population growth

goods and services. Numerous studies and reports

place extreme pressure on reef systems particularly

repeatedly emphasise the important benefits that

along coastlines. Much of the degradation can be

societies obtain from coral reefs. Reefs support i n-situ

minimized with effective integrated coastal

and ex-situ fisheries, are extremely productive, and

management. It is therefore important to implement

protect shores against strong wave action. Reefs of the

action-oriented programmes to halt such degradation

South China Sea contribute to the economic livelihood

and help reefs to recover so that society can continue

of many coastal communities. Reef-related fisheries

to reap the benefits of coral reefs in a more sustainable

form a significant part of fish landings, particularly in the

fashion.

South China Sea where more than 70% of the

population live in the coastal area, and where fish is the

major protein source.

Dr. Chou Loke Ming & Dr. Ridzwan Abdul Rahman

Bangkok, Thailand

January 2004

Reversing Environmental Degradation in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand.

Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Viet Nam

In 1996, the countries bordering the South China Sea requested assistance from UNEP and the GEF in

addressing the issues and problems facing them in the sustainable management of their shared marine

environment. From 1996 to 1998 initial country reports were prepared that formed the basis for the

development of a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, which identified the major water related

environmental issues and problems of the South China Sea. Of the wide range of issues identified the

loss and degradation of coastal habitats, including mangrove, coral reefs, seagrass and coastal

wetlands were seen as the most immediate problem. Over-exploitation of fisheries resources and land-

based sources of pollution were also considered significant issues requiring action.

In 1999 the governments, through the Co-ordinating Body for the Seas of East Asia endorsed a

framework Strategic Action Programme that established targets and timeframes for action. In

December 2000, the GEF Council approved this project with UNEP as the sole Implementing Agency

operating through the Environmental Ministries in the seven participating countries and with over forty

specialised Executing Agencies at national level directly engaged in the project activities.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

2

DISTRIBUTION AND DIVERSITY OF CORAL REEFS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

INTRODUCTION

The southwestern half of the South China Sea lies

over the Sunda shelf at less than 200 m depth,

Global Distribution. Coral reefs thrive best in warm

while the northeastern sector drops to oceanic

tropical waters but extend beyond the tropics in

depths of more than 5,000 m. Coral reefs are

situations where warm currents push through the

liberally distributed along most of the coastlines

tropical belt into the higher latitudes. Southeast Asia

bordering this large marine ecosystem particularly

is recognized as the global centre of coral reefs,

below the Tropic of Cancer (Figure 1.). Major island

both in terms of extent and species diversity. An

groups dot the South China Sea and support

estimated 34% of the earth's coral reefs are located

extensive oceanic reef systems. Approximately 20%

in the seas of Southeast Asia (Burke et al., 2002)

of Southeast Asia's reefs occur in the South China

which occupies only 2.5% of the total sea surface.

Sea. Fringing reefs dominate the near shore waters,

while atoll formations are common in the deeper

areas. Talaue-McManus (2000) highlighted the

ecological and economic importance of the coral

reefs of the South China Sea in the Transboundary

Diagnostic Analysis completed during the

preparatory phase of this project.

Biological Diversity. The Indo-West Pacific marine

biogeographic province has long been recognized

as the global center of marine tropical biodiversity.

Fifty of a global total of seventy coral genera occur

in this marine basin (Tomascik et al., 1997) and 7 of

the 9 giant clam species are found in the nearshore

areas of the South China Sea.

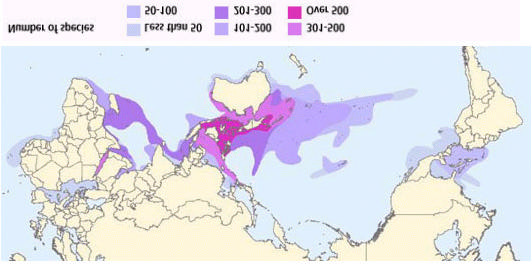

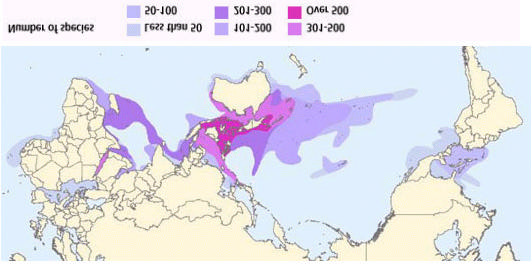

Compared to the Atlantic, the tropical Indo-West

Pacific is very diverse (Figure 2). Only some 35

coral species are found in the Atlantic compared

with over 450 coral species recorded from the

Philippines, 200 from the Red Sea, 117 from South

East India and 57 from the Persian Gulf. The

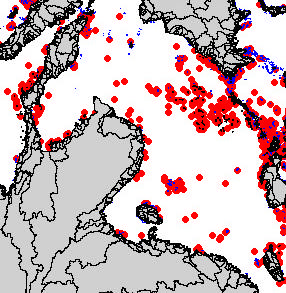

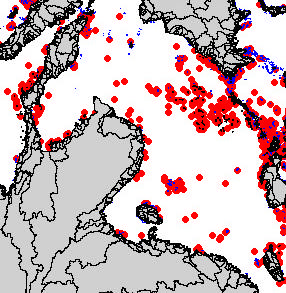

Figure 1 Coral reef distribution in the South China Sea.

location of the South China Sea at the junction

(Sources: UNEP/GEF SCS & Reef at Risk in Southeast

between the Pacific and Indian Ocean basins, has

Asia)

resulted in it becoming a centre of aggregation of

The South China Sea is the largest sea in

species from both Oceans.

Southeast Asia. Bordered by Cambodia, the

People's Republic of China, Brunei, Indonesia,

Coral species. More than half of Southeast Asia's

Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and

hard coral species diversity is found in the South

Vietnam, it forms a semi-enclosed large marine

China Sea. Current information available for sites

ecosystem. Circulation in the South China Sea is

around the South China Sea (Table 1) indicates a

influenced by the twice-annual monsoons. The

wide variation in coral species diversity at different

northeast monsoon towards the end of the year

sites, ranging from between 12 and 351, reflecting

forces surface currents north to south, while the

the influence of physical parameters and human

southwest monsoon that occurs mid year, drives

activity.

currents in the reverse direction. There is also a flow

of Pacific water into the basin interacting with water

from the Indian Ocean.

Figure 2

Distribution and diversity of coral reef species world-wide.

Source: J.E.N. Veron and Mary Stafford-Smith Corals of the World (Cape Ferguson: AIMS, 2000)

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

CORAL REEFS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

3

Hotspots of Biological Diversity. Hotspots of coral

species concerned. The high species richness of

species diversity occur at Nha Trang (Vietnam) with

corals and reef-associated fauna and flora in the

351 species and El Nido (Palawan, Philippines) with

South China Sea also makes this region a valuable

305 species. Records of more than 200 coral

source of genetic and biochemical material.

species occur for a number of sites in Vietnam,

Indonesia and the Philippines. In general, the data

Pharmaceutical products. Coral reefs are a

indicate higher species diversity at the deeper

treasure house of many important biochemical

offshore reefs.

compounds contained within the rich diversity of

reef organisms. Some of these compounds have

Diversity of other marine organisms. The marine

anti-cancer, anti-biotic, anti-viral and anti-oxidation

biological diversity of the South China Sea is

properties. These compounds have great potential

immensely rich. A preliminary assessment of the

in the development of new pharmaceutical,

sea's biological diversity, which is not confined to

cosmetic, and health products.

coral reefs, indicates more than 8,600 species of

plants and animals (Ng & Tan, 2000). Fish alone

One spec ies of cone shell for example that is found

contribute 3,365 species (Randall & Lim, 2000).

in coral reefs has been reported to produce a

This preliminary listing however, excludes many

potentially important drug that can replace

important groups, which are less well studied. Even

morphine. The market value of such a drug is

for those groups, which have been assessed, it was

several billions of dollars and the same species has

noted that many more species remain to be

over a hundred neuro-active compounds. With over

documented.

50 species of cone shells present in coral reefs, the

economic potential of this rich biodiversity is

It is important to note that the South China Sea

enormous. Considering the potential new drugs for

supports a significant number of endemic species.

other biomedical applications, the economic spin-

For example, only 5% of the 1,500 species of

offs are indeed staggering.

sponges in the South China Sea are distributed

throughout the Indo-West Pacific (Hooper et al.,

Coral reefs as nursery areas. Ecologically, coral

2000), and 12% of the 982 species of echinoderms

reefs of the South China Sea are sources of brood

in the South China Sea are endemic (Lane et al.,

stock for many commercially important reef fish and

2000).

invertebrate species. In addition, coral reefs are

important breeding and nursery grounds for many

Global significance of Coral Reefs in the South

pelagic and demersal fish species found in the open

China Sea. If coral reefs are the most diverse

sea. These reefs provide the source of larvae and

tropical marine ecosystems on earth, then the Indo-

juveniles of fish and invertebrates that support the

west Pacific in general and the South China Sea in

capture fisheries in the surrounding ocean. In fact,

particular are home to the most diverse coral reef

the future of the coral live-fish trade in the region is

systems. Marine endemism makes this system all

still dependent on wild brood stock from the reefs.

the more valuable as species loss in this region

translates into total extinction for many of the

Table 1

Numbers of coral genera and species at coral reef locations in the South China Sea.

Site Name

Genera Species

Site Name

Genera Species

Site Name

Genera Species

Cu Lao Cham

39

131 Mu Koh Ang

Thong

38

110 Natuna

63

182

Nha Trang bay

64

351 Mu Koh Samui

45

140 Senayang Lingga

64

217

Con Dao

55

250 Mu Koh Samet

20

41 Batu Malang, Pulau

41

96

Tioman

Phu Quoc

37

89 Sichang Group

38

90 Batu Tikus, Pulau Tinggi

41

79

Ninh Hai

49

197 Sattaheep Group

38

90 Pulau Lang Tengah

39

86

Ca Na bay

48

134 Lan and Phai

20

72 Pulau Lima, Pulau Redang

50

96

Group

Ha Long - Cat Ba

48

170 Chao Lao

41

80 Teluk Jawa, Palau Dayang

35

80

Hai Van - Son Tra

49

129 Prachuab

35

74 Silam,Pulau Baik, Sabah

67

n/a

Bach Long Vi

31

99 Koh Tao Group

41

79 Pulau Linggisan, Pulau

Banggi, Sabah

50

96

Batanes, Basco

16

n/a Song Khla

8

12 Koh Kong

n/a

67

Bolinao/Lingayen Gulf

57

199 Koh Kra

35

80 Koh Sdach group

n/a

67

Masinloc, Zambales

24

n/a Losin

40

90 Koh Rong group

n/a

34

Batangas bay/Maricaban

74

290 Anambas

62

206 Koh Takiev Group

n/a

23

Puerto Galera, Mindoro

62

267 Bangka

37

126 Koh Tang Group

33

70

El Nido, Palawan

74

305 Barelagn-Bintan

62

169 Kompot

n/a

67

Mu Koh Chumporn

31

120 Belitung

55

164 Koh Tunsay Group

n/a

67

Mu Koh Chang

42

130 Karimata

42

192

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

4

CORAL REEF PRODUCTIVITY AND PRESENT STATE

Coral Reef Productivity. A coral reefs' very high

Table 2

List of Major Threats identified at sites

productivity is derived from its structural complexity;

bordering the South China Sea.

its efficient turnover of nutrients; and the high

primary production from unicellular symbiotic algal

Country

Major Threats

in the coral tissues. The evolutionary and ecological

development of this complex system results in a

Cambodia

Over fishing, blast fishing, poison fishing.

series of synergistic and symbiotic processes

Indonesia

Over fishing, blast fishing, sand mining.

manifested at different spatial and time scales in the

Over fishing, blast fishing, poison fishing,

ecosystem. These processes are the key to the reef

Malaysia

trawling.

Over fishing, blast fishing, poison fishing,

systems' transboundary significance, and its

Philippines siltation.

resilience in the face of natural and human induced

stress. The evolution of the reef community is

Thailand

Over fishing, coastal tourism, siltation

reflected in the trophic relationships among reef

Vietnam

Over fishing, poison fishing.

organisms and their complex inter-related life history

strategies. Social and economic benefits are

dependent upon these processes, which provide

Although the impacts of human use, both direct and

essential goods and services to the majority of the

indirect, are generally more severe than impacts

human population in the region.

resulting from natural events, this is not the case

with switches in the El Nino pattern of ocean

Importance of reefs to pelagic species. Food

circulation, which result in warming of the sea

derived from reef fisheries remains one of the most

surface within the Indo-west Pacific in general and

basic and essential commodities to the

the South China Sea in particular.

impoverished but growing coastal populations. In

addition, about a quarter of the diet of pelagic and

Global warming of the sea surface could cause

transboundary migratory fish like the yellowfin tuna

widespread coral mortality at alarming levels as

comes from reef-associated organisms (Grandperrin

illustrated by the consequences of the 1998 El Nino

et al.1978). In addition to trophic dependence on

event when mean sea surface temperature was the

reef-associated organisms, other pelagic species

highest ever recorded.

are dependent on the reef habitat to complete their

life cycle, visiting and using coral reefs as spawning,

Thermal tolerance of corals. Corals in a particular

breeding and nursery grounds.

area are known to tolerate quite narrow ranges of

temperature al though on a global scale different

Threats and Rates of loss of coral reefs. The

populations are able to withstand different

South China Sea has one of the largest areas of

temperature ranges. Those in the Red Sea for

coral reefs of any tropical sea. While natural

example, occur normally in waters that would cause

disturbances such as storms and El Nino related

bleaching of corals in colder water areas. A slight

bleaching events (exacerbated by global changes

shift in temperature of 1-2oC above or below the

brought about by human activities) have an impact

normal threshold level for a period of a few weeks

on reef systems, human activities are currently

may cause corals to bleach. When such

resulting in widespread loss of reef habitats (Arceo

temperature anomalies are prolonged, corals may

et al. 2001).

die. The sea surface temperature rise experienced

during the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

Over the last century, many countries in the region

event between 1997 and 1998 caused mass coral

have undergone rapid economic development and

bleaching worldwide, including in the South China

population growth, particularly in coastal areas.

Sea.

Consequently, human pressures on coral reefs have

increased. Coastal Infrastructure development to

Coral Bleaching. Starting in late 1997 and

support economic growth and the accompanying

continuing through to late 1998, sea temperature

pollution of the marine environment associated with

increased sequentially around the world. Sea

growing human activities have caused degradation

surface temperat ure in most parts of the South

of reefs close to major population centres. Resource

China Sea was raised 2 30 Celsius above the

exploitation has led to extensive coastal degradation

normal seasonal maximum (Wilkinson, C.R. 1998).

and watershed deforestation and erosion have

By April 1998, anomalous hot water temperatures

resulted in increased sedimentation on coral reefs.

appeared in the South China Sea. Heating

All these stresses affect the overall health of the

intensified in May and July, and coral bleaching was

reef systems.

reported from Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand,

Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. This coral

The rates of loss of coral reefs are not precisely

bleaching was followed by mass mortality of

known due to a lack of detailed data and information

scleractinian coral and other zooxanthellae-bearing

on the status of coral reefs over the last few

reef organisms. Coral mortality reached 70 90 %

decades. Threats to coral reefs in Southeast Asia,

extending from the reef flat down to a depth of 15

have been estimated by Burke et al (2002) (Table

meters. Recovery rates varied throughout the

2), who consider that over 80% of Southeast Asia's

region, from full and fast recovery in some reefs of

coral reefs are under threat.

Vietnam located in upwelling areas, to slow, partial

recovery in other countries (Chou, 2000).

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

CORAL REEFS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

5

CORAL REEFS: A DEGRADING HABITAT

techniques such as blast fishing and poisons, to

capture fish on reefs further adds to the loss of coral

Coral reef degradation. Over the past 10 -15

habitat in many countries surroun ding the South

years, progressive degradation of coral reefs in

China Sea.

several locations of the South China Sea has been

noted. Many reefs, which used to be rich and

It has been suggested that despite the long history

pristine now have less live coral cover, and smaller-

of over fishing in the South China Sea, the lag time

sized fish in response particularly to anthropogenic

in ecosystem response, such as the phase shifts

activities. Rapid population growth, land-based

seen in the early 1990's in the Caribbean, may be

pollution, and over-fishing all contribute to this

due to the greater resilience of the reefs in this

decline. In general, coastal resources located near

region as a consequence of their high species

large human population centres have suffered the

diversity (Jackson et al. 2001). Based on recent

most serious degradation.

simulation models (Alino and Dantis 1999) it is

believed that the most immediate threats of

This decline in the health of coral reefs has grave

ecological disaster stem from human actions

detrimental consequences to the social and

including pollution and sedimentation.

economic well-being of the coastal communities that

are directly dependent on reef resources and to the

Most reefs in the South China Sea appear to have

countries concerned through loss of tourism and

reached maximum harvestable potentials around

other reef dependent sources of revenue.

the mid-1970's, (Alino et al., 1996) although in the

case of turtles this level may have been reached

Causes of reef degradation. Rapid population

even earlier. Recent observations in the Turtle

growth along the coast of most countries has

Islands fringing reefs, suggest that mass slaughter

resulted in increasing stress on coral reef resources,

of turtles during World War II caused a reduction of

particularly for food. Many coastal communities are

turtle nesting incidence near these areas that is still

poor and have no means to fish in the open sea or

observable today.

offshore areas, hence, fishing and collecting of

marine organisms from the coral reefs take place

DESTRUCTIVE FISHING.

close to their villages or homes.

As exploitation level increases and fish resources

become depleted, some fishermen choose

destructive techniques to catch fish. The use of

explosives and poisons for fishing is widespread in

many parts of the South China Sea. Burke et al.

(2002) indicated that 50-60% of Southeast Asia's

reefs are threatened by destructive fishing. The

prevalence of destructive fishing such as blast and

poison fishing will exacerbate Malthusian over

fishing (Pauly et al. 1989; Russ 1991) under the

present situation of increased human population

and reduced resource productivity.

Use of Poison. Poison fishing, commonly using

cyanide, to capture food fish live, targets high value

species, which are among the top predators. These

include the Napoleon wrasse, barramundi cod, coral

Hill cutting and construction activities degraded the coral

trout and large groupers. The poison is squirted

reefs near this site

from plastic bottles by divers commonly into reef

Coastal development. Coastal development is

crevices where the fish take refuge. The effects of

recognized as a growing threat throughout the

poison fishing are multiple. Corals are broken to

South China Sea. In most countries, decline in live

retrieve the stunned fish and a wide range of larvae

coral cover is closely associated with coastal

and small fish are killed by the low concentrations.

development that involve activities such as land

Corals are also bleached by the poison at

reclamation, land-clearing, dredging, and sand-

concentrations far below those used by the fishers.

mining, which very often, result in terrestrial soil and

nutrient run-off at the development sites and

Accurate figures for the live food fish trade are

sedimentation on adjacent coral reefs. Many of the

difficult to obtain as official records are for gross

coastal communities and high population density

weights, which include the water in which the fish

urban centres have inadequate sewage treatment

are transported. Poison fishing will continue in the

systems resulting in the release of high levels of

future since the incentives are high. Prices in Hong

nutrients onto reefs that subsequently trigger shifts

Kong for live Napoleon wrasse reach US$ 60-80 per

in reef community structure.

kg. The economic loss to the region from reef

damage is high, estimated at US$ 46 million with

Overfishing.

Overfishing and unmanaged

the industry collapsing within 4 years at current

exploitation of natural resources have resulted in

catch levels. Alternatively, a sustainable hook and

widespread damage to coral reefs in the South

line fisheries option could create net benefit of US$

China Sea. The use of destructive fishing

321.8 million (Llewellyn, G. 1999).

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

6

IMPACTS USE AND VALUE

Bomb fishing. Away from major population centres,

consumption. This is particularly significant for

destructive fishing practices are the greatest threats.

island populations living in remote areas such as the

Explosives are easily made from artificial fertilizer.

Palawan islands (Philippines), islands of Sabah

Schooling reef fish such as, groupers, fusiliers,

(Malaysia), Koh Samui (Thailand). Coastal

surgeon fish, rabbit fish and snappers are targeted

communities also benefit from the collection of

and the explosives are thrown from only 5 meters

ornamental items such as mollusc shells to be sold

distance. Dead and stunned fish are collected by,

as souvenirs.

divers using "hookah" equipment.

The health of the coral reef ecosystem of the South

Damage to the reef is catastrophic as a single beer

China Sea is clearly related to fisheries production

bottle bomb can destroy a reef area of 5 m2, while a

since coral reefs provide habitats for about 80% of

larger gallon container destroys up to 20 m2. On

the fish caught by coastal subsistence and small-

regular bombed reefs, coral mortality may be 50-

scale fishers. The health of the reef system is

80%. The economic loss over the next 20 years is

therefore crucial to the welfare of these communities

conservatively estimated at US$ 3 billion in remote

and degradation and loss can have severe social

areas and US$ 60,800 per km2 in reefs within areas

and economic consequences.

of high tourism potential (Caesar, 1996).

Coral reefs also provide services such as beach and

coastal protection and their aesthetic appeal

provides the basis for the international tourism

market. In areas where storms abound, reefs

provide the first buffer protection to the coastal

habitats against the destructive effects of storm

surges, and against the normal erosion effects of

tidal and long-shore current movements during the

monsoon periods.

Aquarium Trade. The aquarium fish trade

continues to fuel demand for marine ornamentals

with significant exports from the Philippines,

Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam to North America

and Europe. Live corals are also exported mainly to

Bomb fishing

Oriental and European markets. Living "rocks" and

dead corals are also exported as part of the marine

USE AND VALUE

ornamental trade.

About 75% of the population in the nine countries

Aquaculture. Marine aquaculture of coral reef fish

bordering the South China Sea is resident in the

and shellfish is a growing ac tivity in the region as an

coastal zone. The sea and coastal habitats including

increasing number of farms are established to

coral reefs, provide the main source of livelihood for

culture spiny lobsters and groupers in particular.

most of these communities. Reefs support coastal

Juveniles are caught from the reefs and kept in such

fisheries and provide a variety of harvestable marine

farms, while reef benthic invertebrates such as sea

products. For example, coastal fisheries contributed

urchins and mollusks are collected to feed the

1,079,953 tonnes to the total fish production in

cultured species. Overharvesting of wild individuals

Malaysia in 1998, (Dept of Fisheries Malaysia,

to stock such "farms" not only results in changes to

1999). In the Philippines alone, around 10-30% of

the wild population and community of food species

total fisheries production is derived directly from reef

but also reduces the long-term economic viability of

fisheries. Fishery products from reef areas provide

the farms themselves.

the major source of dietary protein and a substantial

proportion is utilised directly through local

Table 3

Aquarium Trade in coral reef organisms.

(Wabnitz, et al., 2003)

No. of invertebrates

No. of invertebrates

Origin

% of total no.

% of total no.

imported

imported

(exporters/ data)

traded

Origin

(importers/ data)

traded

Indonesia

561,506

44

Unknown

2,441,742

80

Philippines

460,817

36

Mexico

246,458

8

Sri Lanka

100,309

8

Indonesia

104,282

3

Solomon Islands

75,305

6

Singapore

68,190

2

Fiji

53,823

4

Fiji

48,358

2

Palau

10,315

1

Sri Lanka

33,782

1

Philippines

29,440

1

Vanuatu

15,904

1

Total

1,262,075

99

Total

2,988,183

98

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

CORAL REEFS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

7

Coral mining Coral mining for lime production is a

anchor dropping at dive sites (as mooring facilities

traditional activity, still practiced in some coastal

are not normally installed), breakage of live corals

villages of Vietnam. Some cement factories use

by inexperienced divers, and from trampling on the

coral rock as a limestone source, and coral rock is

reef flat or gleaning of reefs.

also used for shrimp pond construction in Vietnam.

Coastal Tourism. Many of the South China Sea

countries have developed marine tourism based on

coral reefs. The reefs support the scuba diving

industry and attract divers world-wide. Marine

tourism supports other economic activities such as

the production of handicrafts, food, beverage and

other local cultural products that provide extra

income to local communities and contribute

significantly to the hard currency earnings of the

countries concerned.

The high species diversity of coral reefs, their easy

accessibility and low cost of living make the South

China Sea an attractive destination for marine

tourism. The coral reefs of the countries bordering

Inexperienced divers descending to a coral reef.

the South China Sea should be considered an

Reefs are also significant for recreational

important resource for economic development as

photography and many universities and research

they attract divers and fishing enthusiasts.

institutes in the region focus on reefs for education

and research, contributing to a growing awareness

Reef-based Tourism. The importance of reefs in

of their ecological and economic value.

affecting tourist arrivals is illustrated by the

experience of Peninsular Malaysia. The East coast

Coastal Protection. Coral reefs are important in

islands have more extensive and more diverse reefs

ter ms of coastal protection in many locations

than on the west coast (Wells, 1988). The reefs of

exposed to strong conditions such as in central

the east coast have 55 70% live coral cover

Vietnam, Sabah and Palawan. Reefs are used as

(Wilkinson, 1998) and this has contributed to the

natural harbours for small fishing boats.

high number of tourist arrivals on this side of the

peninsula. Destinations growing in popularity

Economic Value. Assessments of the economic

include El Nido (Philippines), Mu Koh Chang

value of coral reefs take into account both, the direct

(Thailand), Nha Trang (Vietnam), Pulau

and indirect values, and also non-use values.

(Philippines), Layang-Layang (Malaysia) and Sanya

Preliminary data from the Apo Islands (Philippines)

(China). Coastal tourism in the region has increased

indicate the total economic benefit at US$ 400,000

remarkably in the last 15 years but popular

in 2000, when the reefs are well protected.

destinations suffer from an over-burdening of the

Degradation of reefs results in loss of benefits.

ecological carrying capacity.

Cesar et al., (2001) estimated the economic impact

of coral bleaching to fisheries and tourism at El

Tourism Impacts. The tourism industry contributes

Nido, Palawan (Philippines), where a large

to degradation of coral reefs both during the

percentage of corals bleached during the second

development of resorts and from their subsequent

half of 1998. Significant economic losses to tourism

operation. The early construction phase may involve

due to the coral bleaching event at El Nido was

damaging practices of land clearance and even

estimated at US$ 30 million based on the

quarrying of the reef for materials used in resort

assumption that these losses were permanent at a

construction. When the resort is operational,

9% discount rate.

damage may result from improper sewage disposal,

Table 4 Total Number of Visitors to the Malaysian Marine Park Islands.

Year

East Coast

West Coast (Tioman,

(Pulau Payar)

Redang, Mersing)

Total

Local

Foreign

Local

Foreign

Local

Foreign

1999

16,557

66,689

157,289

136,935

173,846

203,624

2000

19,944

68,836

189,914

169,164

209,858

238,000

2001

38,027

89,514

221,256

135,436

259,283

224,950

2002

56,259

77,516

118,864

34,392

175,123

111,908

Total

130,787

302,555

687,323

475,927

818,110

778,482

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

8

DEMONSTRATION SITES

PURPOSE OF THE DEMONSTRATION SITES

CHARACTERISING POTENTIAL DEMONSTRATION SITES

The primary purpose of the demonstration sites

At its first meeting the Regional Working Group on

selected under this project is to demonstrate

Coral Reefs (RWG-CR) discussed and agreed upon

actions, which either "reverse" environmental

an ideal list of data and informa tion, which should

degradation or will demonstrate methods of

be assembled for all potential demonstration sites

reducing degradation trends if adopted and applied

(UNEP, 2002a). National Committees or sub-

at a wider scale. In the case of coral reefs in the

committees working under the direction of the

South China Sea marine basin, the major cause of

national focal point then proceeded to identify

the degradation is destructive use of coral reef

potential sites, and to assemble the required data

resources. Therefore the demonstration activities

and information. It soon became apparent that an

will focus on proper management of coral reef

ideal listing of data that could be used as the basis

resources at specific sites, with the aim of

for criteria and indicators to prioritise sites could not

transfering successful practices and experiences to

be assembled for all potential demonstration sites

other, similar sites.

due to the unavailability of data sets from certain

locations or for certain parameters. The finally

The types of demonstration sites selected within the

agreed set of data and information which the

coral reef sub-component of the project will be

regional working group agreed to use in the

designed to illustrate sustainable use of coral reefs

subsequent selection procedures represent a

in the region, in particular in the priority areas

compromise between available data sets and the

identified during the preparatory phase (first 2

ideal set (UNEP, 2002b).

years) of the project. To date seventeen

demonstration site proposals have been prepared

A first step in comparing data and information on a

by the national coral reef committees (or working

regional basis involved the use of a cluster analysis

groups) encompassing a wide range of different

to determine the relationships, in terms of the

demonstration activities, including:

similarity and difference between all sites. Whilst all

countries have determined national priorities for

·

Enhancing capacity for monitoring and

conservation and sustainable use of their coral reef

research, at Phu Quoc islands, Nihn Hai,

systems these priorities have been, determined

and Koh Tunsay;

independently, within each country resulting in

·

Community-based management , at

priorities, which do not necessarily reflect regional

Belitung, Mu Koh Samui, Mu Koh

priorities, nor do they necessarily include

Angthong;

consideration of transboundary issues, nor regional

·

Establishing marine protected areas or

and global significance. By conducting a cluster

sanctuaries, at Batangas Bay, Calamianes

analysis using an identical set of data and

Island Group;

information from all countries (Table 5) regional

·

Sustainable tourism, at Mu Koh Angthong,

comparability in the subsequent prioritisation

Mu Koh Chang,

process is assured.

·

Sustainable financing/alternative livelihood,

at Masinloc, Zambales, Anda-Bolinao-

COMPARING SIMILARITY AND DIFFERENCE.

Bani-Alaminos,

·

Legal instrument and law enforcement, at

The Regional Scientific and Technical Committee

Belitung, Mu Koh Angthong,

considered the process of determining regional

·

Pilot activities on restoration of coral reefs,

priorities for action and recommended a three step

at Koh Tunsay, Mu Koh Samui

process (UNEP, 2002c) as follows:

·

Data and information for the site to be

The proposed demonstration activities involve

assembled by the national committees, (or

different organisations and different groups of

working groups) from the participating

people, including government agencies, local

countries, based on the regionally agreed

governments and organisations, non-governmental

format;

organisations, local communities, media, and civil

·

Conduct a cluster analysis to determine

society, in designing and executing the proposed

similarity and difference between all

activities.

potential sites;

·

Determine regional priority on the basis of

Building on the networks of individuals and

a rank score according to a prior agreed,

institutions developed during the preparatory phase

sets of criteria and indicators.

of the project (2002 - 2003) regional mechanisms

will be established to ensure sharing of experiences

In deciding upon the use of a cluster analysis to

and exchange of kn owledge regarding "good

group similar sites the RSTC recognised that the

practices" between sites and between countries.

available funds were unlikely to be sufficient to

The Regional Working Group on Coral Reefs will

support interventions at all sites identified by the

continue to provide advice and guidance regarding

National Committees and Sub-committees. By

the establishment and operation of the

grouping sites with similar characteristics and

demonstration sites once selected and to manage

selecting sites from the groups the interventions

the regional co-ordination and exchange between

could be chosen to maximise the range of biological

sites in different countries.

diversity represented around the margins of the

South China Sea.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

CORAL REEFS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

9

Table 5

Uniform data set for coral reef potential demonstration sites used in determining similarity and

difference between sites.

No. of

Hard

live

No. of

No. of

No. of

No. of

endangered

Site Name

coral

coral

algae crustacean echinoderm coral

Other

and

species cover

reef fish ecosystem

(%)

spp.

species

species

species

threatened

species

Viet Nam

Cu Lao Cham

131

33.9

122

84

4

178

1

4

Nha Trang bay

351

26.4

55

69

27

222

2

3

Con Dao

250

23.3

84

110

44

202

2

4

Phu Quoc

89

42.2

98

9

32

135

2

3

Ninh Hai

197

36.9

190

24

13

147

1

4

Ca Na bay

134

40.5

163

46

26

211

1

3

Ha Long - Cat Ba

170

43

94

25

7

34

2

4

Hai Van - Son Tra

129

50.5

103

60

12

132

1

4

Bach Long Vi

99

21.7

46

16

8

46

M

2

Philippines

Batanes, Basco

M

55.00

41

M

M

86

1

3

Bolinao/Lingayen Gulf

199

40.00

224

M

M

328

2

4

Masinloc, Zambales

M

33.00

57

M

M

249

2

4

Batangas bay/Maricaban

290

48.00

141

M

M

155

2

4

Puerto Galera, Mindoro

267

33.00

75

M

M

333

2

5

El Nido, Palawan

305

40.00

129

M

M

480

2

5

Thailand

Mu Koh Chumporn

120

55

M

304

21

106

4

5

Mu Koh Chang

130

40

43

250

20

113

4

6

Mu Koh Ang Thong

110

55

7

136

21

106

4

1

Mu Koh Samui

140

40

7

136

21

106

4

5

Mu Koh Samet

41

35

38

134

11

74

4

5

Sichang Group

90

20

40

304

11

86

4

2

Sattaheep Group

90

33

40

304

15

75

4

2

Lan and Phai Group

72

18

40

304

15

75

2

2

Chao Lao

80

30

33

123

12

105

2

3

Prachuab

74

40

18

106

16

162

2

4

Koh Tao Group

79

45

7

136

21

106

2

4

Song Khla

12

20

2

M

M

30

2

2

Koh Kra

80

40

M

M

M

80

1

2

Losin

90

40

M

M

M

90

1

2

Indonesia

Anambas

206

M

26

24

25

128

3

2

Bangka

126

M

M

25

23

169

3

2

Belitung

164

38.46

M

10

35

170

3

2

Karimata

192

M

M

15

15

200

3

2

Malaysia

Batu Malang, Pulau

96

62.6

3.8

Tioman

M

M

123

1

4

Pulau Lang Tengah

86

41.3

3.1

M

M

117

2

4

Pulau Lima, Pulau Redang

96

46.3

10

M

M

113

1

4

Teluk Jawa, Palau Dayang

80

38.4

11.9

M

M

156

1

4

Tun Mustapha, Sabah

252

M

69

M

45

375

4

4

Cambodia

KKCR2

67

29.3

M

M

1

51

2

M

SHVCR1

34

23.1

M

M

14

6

3

M

SHVCR2

23

58.1

3

M

M

51

3

M

SHVCR3

70

M

M

M

14

42

3

M

KEPCR1

67

41

M

M

14

51

3

M

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

10

GROUPING AND PRIORITISING DEMONSTRATION SITES

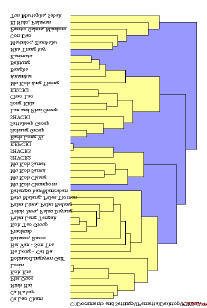

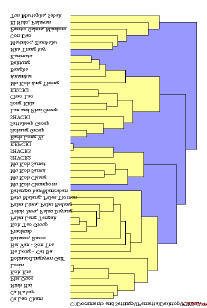

Clustering sites. Figure 3 presents the dendrogram

FINALISATION OF RANK SCORES AND INDICATORS

resulting from a cluster analysis of the data

presented in Table 5 using the Clustan6 software.

Biological Indicators. At the same time that the

Four clusters of sites are apparent, the lower cluster

group agreed on the data and information required

consisting of a grouping of outlying sites that for

to characterise the sites an initial discussion

various reasons are somewhat distinct from the

regarding the criteria and indicators that could be

remainder of the set. The proposed demonstrations

used as a mechanism for scaling transboundary,

sites were divided by the RWG-CR into 3 groups.

national, regional, and global significance was

undertaken. Criteria and indicators were initially

Figure 3

Graphic result of cluster analysis.

identified for the criteria covering indicators of

environmental and biological diversity and

agreement reached regarding the application of

rank scores that could be applied objectively to the

data from each site. The outcome of this process is

presented in Table 6 in which the original 43

potential demonstration sites have been aggregated

into groups and ranked in descending order of

priority based on the rank score for environmental

and biological diversity indicators.

Rank Scores. Social and economic criteria and

indicators were also reviewed and discussed, and

the rank scores agreed, covering such elements as

the reversibility of current threats, national priority,

level of direct stakeholder involvement in the current

management regime, soco-economic values, and

potential for co-financing support. The RGW-CR

recognised that many of these parameters could not

be measured objectively without the detailed

investigations and consultations required to prepare

a full proposal hence scoring based on this set of

parameters was only conducted for those sites for

which demonstration site proposals had been

prepared and discussed with local stakeholders. In

deciding upon the proportion of the final score that

Table 6 Rank scores of coral reef potential demonstration

should be assigned to an individual proposal the

sites based on agreed environmental and

RWG-CR agreed that since the environmental and

biological diversity criteria and indicators.

biological parameters were more objective and

easily verifiable, greater weight should be assigned

Site Name

Rank

Site Name

Rank

scores

scores

to this category of criteria and indicators than to the

social and economic criteria. It was agreed that the

First Group

Second Group

Ninh Hai

80 Mu Koh Ang

64

two groups of scores should be combined in the

Mu Koh Chang

76 Thong

ratio 70:30 respectively and the final rank score is

Mu Koh Chumporn

71 Belitung

55.5

presented in Table 7.

Mu Koh Samui

71 Anambas

52.5

Table 7 Rank scores for demonstration site proposals.

Ca Na bay

61 Karimata

51.5

Batangas

59 Chao Lao

50

Environ.

Socio-

Total

Cu Lao Cham

57.5 Sichang Group

48

Site Name

rank

econ.

score

Koh Tao Group

57 SHVCR1

46.5

Score

Score

Mu Koh Samet

56 Sattaheep Group

45

First Group

Phu Quoc

55.5 KKCR2

45

Ninh Hai

80

55

72.5

Prachuab

55 Bangka

43.5

Mu Koh Chang

76

69

73.9

Ha Long - Cat Ba

54 Lan and Phai

40

Mu Koh Chumporn

71

52

65.3

Bolinao/Lingayan

52 Group

Mu Koh Samui

71

50

64.7

Hai Van - Son Tra

51.5 Song Khla

28

Batangas

59

44

54.5

Batu Malang, Pulau

Phu Quoc

55.5

57 55.95

Tioman

51.5 Bach Long Vi

27

Bolinao/Lingayan

52

48

50.8

Pulau Lang Tengah

47

Batu Malang, Pulau Tioman

51.5

39 47.75

Teluk Jawa, Palau

Pulau Lang Tengah

47

50

47.9

Dayang

46.5

Third Group

KEPCR1

35.5

57 41.95

SHVCR2

46.5 El Nido, Palawan

80.5

Second Cluster

Pulau Lima, Pulau

Mu Koh Ang Thong

64

48

59.2

Redang

43.5 Tun Mustapha

Sabah

69.5

Belitung

55.5

47 52.95

Losin

41.5 Nha Trang bay

67.5

KKCR2

45

52

47.1

Batanes, Basco

40.5 Con Dao

66

Third Cluster

Koh Kra

39.5 Puerto Galera

61.5

Tun Mustapha, Sabah

69.5

70 69.65

KEPCR1

35.5 Macinloc

50

Macinloc

50

57

52.1

SHVCR3

28.5

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

CORAL REEFS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A 11

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aliño, P.M., C.L. Nanola, Jr., D.G. Ochavillo and M.C. Ranola. 1996. The fisheries potential of the Kalayaan

Island Group, South China Sea. Proc. 1st International Conf. Marine Biology of Hong Kong and the South

China Se a.

Aliño, P.M. and A. Dantis. 1999. Lessons from the biodiversity studies of reefs: Going beyond quantities and

qualities of marine life. Proceedings of the Symposium on Marine Biodiversity in the Visayas and

Mindanao. University of the Philippines in the Visayas, Miag-ao. Iloilo. Pp. 78-85.

Annual Fisheries Statistics 1999, Vol 1. Dept of Fisheries Malaysia, 1999. p. 21.

Arceo, H., M. Quibilan, P. Aliño, G. Lim and W. Licuanan. 2001. Coral bleaching in Philippine reefs: Coincident

evidences with mesoscale thermal anomalies. Bull. Mar. Sci. 69(2):579-593.

Burke, L., Selig, E. and M. Spalding. 2002. Reefs at Risk in Southeast Asia. World Resources Institute,

Washington, DC.

Caesar, H. 1996. Economic analysis of Indonesian coral reefs. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Cesar, H., Pet-Soede, L., Quibilan, M.C.C., Aliño, P.M., Arceo, H.O., Bacudo, I.V., and Francisco, H. 2001. First

Evaluation of the Impacts of the 1988 Coral Bleaching Event to Fisheries and Tourism in the Philippines.

Chou, L.M. 2000. Southeast Asian reefs - status update: Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore,

Thailand, Vietnam. In Wilkinson, C.R. (Ed.) Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2000. p. 117-129.

Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville.

Colette Wabnitz, Michelle Taylor, Edmund Green and Tries Razak. 2003 From Ocean to Aquarium: The Global

Trade in marine Ornamental Species. UNEP-WCMC Biodiversity series No. 17.

Grandperrin, R. 1978. Importance of reefs to ocean production. In: Crossland, J. and Grandperrin, R. South

Pacific Commission (Noumea, New Caledonia) Fisheries Newsletter 15: 11-13.

Hooper, J.N.A., Kennedy, J.A. and R.W.N. van Soest. 2000. Annotated checklist of sponges (Porifera) of the

South China Sea region. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. Supplement 8: 125-207.

Jackson, J.B.C., M.X. Kriby, W.H. Berger, K.A. Bjorndal, L.W. Botsford, B.J. Bourque, R.H. Bradbury, R. Cooke,

J. Erlandson, J.A. Estes, T.P. Hughes, S. Kidwell, C.B. Lange, H.S. Lenihan, J.M. Pandolfi, C.H. Peterson,

R.S. Steneck, M.J. Tegner and R.R. Warner. 2001. Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal

ecosystems. Science 293: 629-638.

Lane, D.J.W., Marsh, L.M., Vanden Spiegel, D., and F.W.E. Rowe. 2000. Echinoderm fauna of the South China

Sea: An inventory and analysis of distribution patterns. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. Supplement 8: 459-493.

Llewellyn, G. 1999. Review of existing laws and policies relating to migratory marine species conservation and

commercial and coastal fisheries. Unpubl. m.s.

Ng, P.K.L. and K.S. Tan. 2000. The state of marine biodiversity in the South China Sea. Raffles Bulletin of

Zoology. Supplement N. 8: 3-7.

Pauly, D., G. Silvestre and I.R. Smith. 1989. On development, fisheries and dynamite: A brief review of tropical

fisheries management. Nat. Resour. Modelling 3: 307-329.

Randall, J.E. and K.K.P. Lim (Eds.). 2000. A checklist of the fishes of the South China Sea. Raffles Bulletin of

Zoology. Supplement 8: 569-667.

Roberts, C.M., C.J. McClean, J.E.N. Veron, J.P. Hawkins, G.R. Allen, D.E. McAllister, C.G. Mittermeier, F.W.

Schueler, M. Spalding, F. Wells, C. Vynne and T.B. Werner. 2002. Marine biodiversity hotspots and

conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 295: 1280-1284.

Russ, G.R. 1991. Coral Reef Fisheries: Effects and Yields, p. 601-635. In P.F. Sale. (ed.) The ecology of fishes

on coral reefs. Acade mic Press, Inc., New York, 754p.

Talaue-McManus, L. 2000. Transboundary diagnostic analysis for the South China Sea. EAS/RCU Technical

Report Series No. 14. UNEP, Bangkok. Thailand.

Westmacott, S., Teleki, K. Wells, S, and West, J.M., (2000). Management of bleached and severely damaged

coral reefs. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, U.K. vii + 36 pp.

Wilkinson, C.R. (Ed.) 1998. Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 1998. Australian Institute of Marine Science,

Townsville.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MEMBERS OF THE REGIONAL WORKING GROUP ON CORAL REEFS

Mr. Abdul Khalil bin Abdul Karim, Marine Parks Branch, Department of Fisheries, Malaysia, Jalan Sultan

Salahuddin, 50628 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia, Tel: (60 3) 2698 2500; DL: 26982700, Mobile: (60) 19

330 4142, Fax: (60 3) 2691 3199, E-mail: abkhalil@hotmail.com; abkhalil@yahoo.com

Dr. Ridzwan Abdul Rahman, Borneo Marine Research Institute, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Sepangar Bay,

Locked Bag 2073, 88999 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia, Tel: (60 88) 320 266; 320 121, Mobile: (60)

13 864 4011, Fax: (60 88) 320 261, E-mail: ridzwan@ums.edu.my

Dr. Porfirio M. Aliño, Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City 1101,

Philippines, Tel: (63 2) 922 3949; 922 3921, Mobile: (63) 917 838 7042, Fax: (63 2) 924 7678, E-mail:

pmalino@upmsi.ph

Dr. Chou Loke Ming, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, National University of Singapore,

14 Science Drive 4, Singapore, Tel: (65) 6874 2696, Mobile: (65) 9 734 9863, Fax: (65) 6779 2486,

E-mail: dbsclm@nus.edu.sg

Mr. Yihang Jiang, Senior Expert, UNEP/GEF Project Co-ordinating Unit, United Nations Environment

Programme, 9th Floor, Block A, United Nations Building, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand,

Tel: (66 2) 288 2084, Fax: (66 2) 288 1094; 281 2428, E-mail: jiang.unescap@un.org

Mr. Kim Sour, Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, 186 Norodom Boulevard,

PO Box 582, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Tel: (855 23) 210 565, Mobile: (855) 12 942 640, Fax: (855 23)

216 829, E-mail: sourkim@hotmail.com; catfish@camnet.com.kh

Dr. Suharsono, Research Center for Oceanography LIPI, Puslit OSEANOGRAFI - LIPI, Pasir Putih 1 Ancol

Timur, Jakarta UTARA, Indonesia, Tel: (62 21) 64713850 ext 202; 3143080: 102, Mobile: (62) 816 721

387, Fax: (62 21) 64711948; 327 958, E-mail: shar@indo.net.id; harsono@coremap. or.id

Dr. Vo Si Tuan, Institute of Oceanography, 01 Cau Da Street, Nha Trang City, Vietnam, Tel: (84 58) 590 205;

871134, Mobile: (84) 91 4017 058, Fax: (84 58) 590 034, E-mail: thuysinh@dng.vnn.vn

Dr. Thamasak Yeemin, Marine Biodiversity Research Group, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science,

Ramkhamhaeng University, Huamark, Bangkok 10240, Thailand, Tel: (66 2) 319 5219 ext. 240, 3108415,

Mobile: (66) 1 842 3056, Fax: (66 2) 310 8415, E-mail: thamsakyeemin@yahoo.com

UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project Co-ordinating Unit

United Nations Building

Rajadamnoern Nok

Bangkok 10200

Thailand

Department of Fisheries

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries

186 Norodom Boulevard

Phnom Penh

Cambodia

Research Center for Oceanography LIPI

Puslit OSEANOGRAFI - LIPI

Pasir Putih 1 Ancol Timur

Jakarta UTARA

Indonesia

Marine Parks Branch

Department of Fisheries, Malaysia

Jalan Sultan Salahuddin

50628 Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia

Marine Science Institute

University of the Philippines

Diliman, Quezon City 1101

Philippines

Marine Biodiversity Research Group

Department of Biology, Faculty of Science

Ramkhamhaeng University

Bangkok 10240

Thailand

Institute of Oceanography

01 Cau Da Street

Nha Trang City

Viet Nam