United Nations

UNEP/GEF South China Sea

Global Environment

Environment Programme

Project

Facility

"Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends

in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand"

National Reports

on the

Fish Stocks and Habitats of Regional, Global

and Transboundary Significance

in the South China Sea

First published in Thailand in 2007 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

Copyright © 2007, United Nations Environment Programme

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit

purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the

source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication

as a source.

No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose without prior

permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme.

UNEP/GEF

Project Co-ordinating Unit,

United Nations Environment Programme,

UN Building, 2nd Floor Block B, Rajdamnern Avenue,

Bangkok 10200, Thailand.

Tel.

+66 2 288 1886

Fax.

+66 2 288 1094

http://www.unepscs.org

DISCLAIMER:

The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of UNEP or the GEF. The

designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever

on the part of UNEP, of the GEF, or of any cooperating organisation concerning the legal status of

any country, territory, city or area, of its authorities, or of the delineation of its territories or boundaries.

Cover Photo: Coastal fishing village of Phu Quoc Island, Viet Nam by Mr. Christopher Paterson.

For citation purposes this document may be cited as:

UNEP, 2007. National Reports on the Fish Stocks and Habitats of Regional, Global, and

Transboundary Significance in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 15.

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES

INTRODUCTION

The South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand is a global centre of shallow water marine biological

diversity, supporting a significant world fishery that is important to the food security of, and as a

source of export income for, Southeast Asian countries. Landings from this area contribute

approximately 10 percent of reported global fisheries production per annum and make significant

contributions to the economies, of countries bordering the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea.

The majority of fisheries are small-scale in nature, and fish are landed in a large number of

decentralised locations for distribution through complex marketing networks at the community level.

As a consequence estimates of fisheries production are considered to be gross underestimates and

do not adequately reflect the importance of the artisanal or subsistence production to the fisheries

sector as a whole.

The majority of Southeast Asian countries are among the top 20 capture fisheries producing countries

in the world, with some experiencing annual increases in production of up to 5 percent. Pelagic fishes

dominate landings by volume and value, as most demersal fisheries are over-exploited. It is well

accepted, however, that regional fisheries statistics rarely reflect: (a) production from small-scale

coastal fisheries, (b) the high level participation of coastal communities in fishing, or (c) the social and

economic importance of artisanal and subsistence fishing to coastal communities.

Fish stocks in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand are subject to high levels of fishing effort,

such that stocks of most economically important species are considered to be fully fished or

overexploited. Increasing global demand for fisheries products, and the dependence of coastal

communities on fish for food and income results in a continued increase in fishing effort. This has led

to "fishing down the marine food chain in the region", coupled with an increasing dependence of the

artisanal sector on small pelagic species due to declining availability of demersal species.

The fisheries and habitat components of the UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project focus on the critical

role that habitats such as mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass, and wetlands play in sustaining fisheries

production in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand. These habitats are known to act as refuges

for most economically important fish species during critical stages of their life-cycles including as

larvae, for spawning, and for feeding. These habitats therefore play an important role in recruitment

and maintenance of fish stocks.

Declining fish availability, coupled with over-capacity and the dependence of the small-scale sector on

coastal fisheries for income generation, has led to the adoption of destructive fishing practices by

some fishers in order to maintain incomes and food production in the short-term. Fisheries trends

suggest that production from capture fisheries will decline over coming years unless total fishing effort

and capacity are reduced. The obvious problem in the reduction of fishing capacity is that most

fisheries are small-scale with the majority of participants (and their families) being highly dependent

on fisheries for income, food and well-being.

Whilst actions aimed at reducing the rate of loss of coastal habitats of significance to fisheries have

been implemented by the countries bordering the South China Sea, the decadal rates of loss of such

habitats remain high: seagrass (30%); mangroves (16%); and coral reefs (16%) (UNEP, 2007a).

Increasing levels of fishing effort, coupled with continued decline in the total area of habitats critical to

the life-cycles of most species, have raised serious concerns for the long-term sustainability of

artisanal fisheries in the region.

The dilemma for the fisheries and environment sectors is that conservation of habitat does not

necessarily result in increased fish stocks and lowering of fishing effort does not necessarily result in

improved habitat condition. Although fish production is intrinsically linked to the quality and extent of

habitats; and although the dependence of coastal communities on fish for food and income is high;

understanding of this linkage is limited, such that intensive fishing in inshore areas has been identified

as the key factor contributing to the continued loss of habitats and biodiversity in the region (UNEP,

2006a). The use of inappropriate and destructive gear and practices, such as the use of demersal

trawls and push nets in seagrass areas, and the use of poisons and explosives to catch fish in coral

reef areas, is of continuing concern with respect to the degradation and loss of habitats and

biodiversity.

i

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES

The expert members of the regional working groups on fisheries and coastal habitats of the South

China Sea Project have agreed that intensive, inshore fishing presents numerous threats to coastal

habitats and biodiversity in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand including:

· Degradation and loss of habitats and biodiversity caused by intensive use of inappropriate

and destructive fishing gear and practices in sensitive habitat areas;

· Reduced biomass of fish species of transboundary significance caused by growth and

recruitment over-fishing resulting from the targeting and capture of juvenile fish, fish in

spawning aggregations, and pre-recruits;

· Changes in marine community structure caused by direct reductions of populations

representing specific trophic levels of the community; and

· Decreased abundance and geographical range of rare and endangered species caused by

fishing activities conducted in critical habitat areas.

These threats coupled with the fact that many marine fisheries in Southeast Asia are over-capitalised,

unregulated, and subjected to illegal fishing have provided the impetus for the development of

innovative approaches to the management of fisheries in the region. Significant efforts are being

made in most countries to decentralise the responsibility for fisheries management to the local level

with the aim of establishing co-management particularly of demersal fish stocks. However, the

intrinsic relationship between fish stocks and their habitats necessitates that fisheries management

involving decentralised and rights-based systems will need to incorporate strategies that foster the

improved management of fish life-cycle and critical habitat linkages.

The key focus of the fisheries component of the UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project has been to

develop a mechanism to facilitate improved management of the critical linkages between fish stocks

and their habitats in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand. In this connection the UNEP/GEF

Regional Working Group on Fisheries has collaborated with SEAFDEC to establish a system of

fisheries refugia in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand that focuses on the critical links between

fish stocks and their habitats.

The "National Reports on the Fish Stocks and Habitats of Regional, Global, and Transboundary

Significance in the South China Sea" contained in this publication were prepared during the

preparatory phase of the South China Sea project by the government designated focal points for

fisheries from Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam. Each focal point for

fisheries has compiled in their respective National Reports, available information relating to: the status

and threats of important fish stocks; habitats and areas of importance in the maintenance of exploited

fish stocks; and existing management regimes. The reports were utilised during the operational phase

of the project as an important information resource in the identification of fisheries refugia sites and

development of a regional strategy for the establishment and management of fisheries refugia.

Christopher Paterson, Fisheries Expert

UNEP/GEF Project Co-ordinating Unit

United Nations Environment Programme

ii

United Nations

UNEP/GEF South China Sea

Global Environment

Environment Programme

Project

Facility

NATIONAL REPORT

on

The Fish Stocks and Habitats of Regional, Global, and

Transboundary Significance

in the South China Sea

CAMBODIA

Mr. Ing Try

Focal Point for Fisheries

Fisheries Administration, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

186 Norodom Blvd.

P.O. Box 582, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES - CAMBODIA

Table of Contents

1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1

1.1 OVERVIEW OF CAMBODIA'S FISHERIES SECTOR ......................................................................1

1.1.1 Total catch by fishing area, port of landing or province (by species/species

group, 1990 onwards)................................................................................................1

1.1.2 Fishing effort by gear (number of fishing days/number of boats) ..............................4

1.1.2.1 Trawl (Khmer name Uon Ohs)...................................................................... 5

1.1.2.2 Purse seine/ring net (Khmer name Uon Tith) ............................................... 6

1.1.2.3 Gill net (Khmer name Mong Paehk) ............................................................. 7

1.1.2.4 Other (push nets, trolling, hand line, long line, trap)................................... 10

1.1.3 Economic value of catch (estimated or actual)........................................................12

1.1.4 Importance of the fisheries sector in terms of employment and dependence.........13

2.

SPECIES OF REGIONAL, GLOBAL AND/OR TRANSBOUNDARY SIGNIFICANCE.............14

2.1 RANKING OF IMPORTANCE IN TERMS OF LANDINGS, VALUE, STATUS AND FOOD SECURITY ......14

2.1.1 Landings ..................................................................................................................14

2.1.2 Local Market Value (local currency, year) ...............................................................14

2.1.3 Status.......................................................................................................................17

2.1.4 Food security (locally)..............................................................................................18

2.2 BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY OF THE PRIORITY SPECIES...............................................................18

2.2.1 Pelagic species........................................................................................................20

2.2.2 Demersal species ....................................................................................................22

2.2.3 Commercially exploited invertebrates......................................................................22

3. CURRENT

STATUS & THREATS..............................................................................................22

3.1 STATUS OF THE FISHERY IN TERMS OF CPUE.......................................................................22

3.2 STATUS OF FISH STOCKS BASED ON HISTORICAL REVIEW OF LANDINGS AND CPUE...............23

3.3 THREATS.............................................................................................................................24

3.3.1 Current .....................................................................................................................24

3.3.2 Potential ...................................................................................................................26

4.

HABITATS & AREAS OF IMPORTANCE IN THE MAINTENANCE OF EXPLOITED FISH

STOCKS......................................................................................................................................27

4.1 DESCRIPTION OF THE PHYSICAL, CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF KNOWN

SPAWNING, NURSERY, FEEDING, AND FISHING GROUNDS ........................................................27

4.2 UNKOWN ISSUES SUCH AS STOCKS WITH UNDEFINED SPAWNING GROUNDS .............................30

4.3 THREATS, CURRENT AND POTENTIAL .....................................................................................31

4.4 RANKING OF HABITATS.........................................................................................................31

4.4.1 Ranking for association with species of importance to food security ......................31

4.4.2 Ranking for species of high value............................................................................32

4.4.3 Ranking for endangered, rare and threatened species ...........................................32

5. CURRENT

MANAGEMENT REGIMES......................................................................................32

5.1 LEGAL INSTRUMENTS ...........................................................................................................32

5.2 INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS (RESEARCH, MONITORING, CONTROL & ENFORCEMENT) .........33

5.3 OVERVIEW OF PATTERNS OF RESOURCE OWNERSHIP AND TRADITIONAL UTILISATION ...............33

5.4 HUMAN AND INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITY ..................................................................................33

5.5 REVIEW OF STAKEHOLDERS..................................................................................................34

6. RECOMMENDED ACTIONS ......................................................................................................34

REFERENCES......................................................................................................................................35

ii

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA 1

1. BACKGROUND

1.1

Overview of Cambodia's Fisheries Sector

Cambodia's fisheries and aquaculture play an important role in the national economy and contribute to

food security. The sector provides employment and economic benefits to Cambodians involved in its

activities. The Ministry of Planning estimated in 2002 that Cambodia derives 16% of its GDP from the

fisheries sector.

During recent decades, the productivity of Cambodia's fisheries resources, including fishes,

crustaceans, and molluscs, has declined significantly. This is largely due to increased pressures on fish

stocks and their habitats associated with burgeoning coastal populations in Cambodia. Increased

demand for fisheries products, and the associated improvements in fishing technology, have

contributed to this problem. Cambodia is an ASEAN country bordering the Gulf of Thailand, with a

coastline of 435km extending from the Thai border in the north to the border with Viet Nam in the south.

Cambodia's fisheries are divided into inland and marine capture fisheries. Inland capture fisheries are

significantly more important to Cambodians than marine fisheries, accounting for more than 70% of

Cambodia's total volume of fish production. In terms of value, however, marine fisheries account for

nearly 40% of the country's fisheries production (Try, 2001).

A few comments regarding the accuracy of Cambodian fisheries statistics are necessary. The statistics

presented in this report are the most accurate available to the Department of Fisheries (DoF), however,

a reliable system for the systematic collection of fisheries information and data has not yet been

established in Cambodia. The fact that fish are not landed at central locations, together with direct

exports by foreign vessels and other factors, contribute to inaccuracies. Fish caught by subsistence

fishers are often not included in the official statistics, and as such, the statistics do not adequately

reflect the importance of fisheries to small-scale subsistence fishers in Cambodia.

1.1.1 Total catch by fishing area, port of landing or province (by species/species group, 1990

onwards)

The coastal area of Cambodia is divided into two provinces, Koh Kong in the north and Kampot in the

south, and two municipalities, Sihanoukville and Kep (Figure 1). Cambodia's marine capture fisheries

are characterised by a multitude of species and the use of a range of fishing gears. Reference to DoF

fisheries statistics (Table 1) indicates that fisheries production in Cambodia has developed considerably

since 1988 when changes to government policy created free market and free election systems.

Marine fisheries production as recorded by DoF has not yet shown a decrease by species and landing

place, although anecdotal infromations suggests that the average size of many economically important

fish species traded in domestic markets is declining. The records of production from marine capture

fisheries have been irregular in some periods (Table 1).

Table 1 indicates that total fisheries production increased significantly after 1999. This is a result of

modifications to the DoF's system for the collection of inland fisheries statistics made through the

Freshwater Capture Fisheries Management Project. A corresponding system for the collection of

marine capture fisheries statistics does not exist. The DoF is seeking assistance from NGOs and

regional and international organisations in resolving this problem.

Marine fisheries production by province and municipality from 1992 to 2001 is shown in Tables 2 to 5.

These statistics are not at the species level, but grouped according to higher taxa and commercial or

market names. The data in these tables do not include catches made by local and foreign fleets

operating legally or illegally in Cambodia and then landed in ports of other countries such as Thailand

or Viet Nam. The DoF estimates that fish caught outside Cambodian waters constitute around one

quarter of the recorded production. For Kep municipality there are no data from 1980 to 1996, due to

the institution of the administrative structure for this municipality only occurring in 1996.

The aquaculture of shrimp was introduced to Cambodia in 1993, however, this business collapsed in

1998. At present, all shrimp farms are closed. The culture of seaweed began in 2001.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

2 NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA

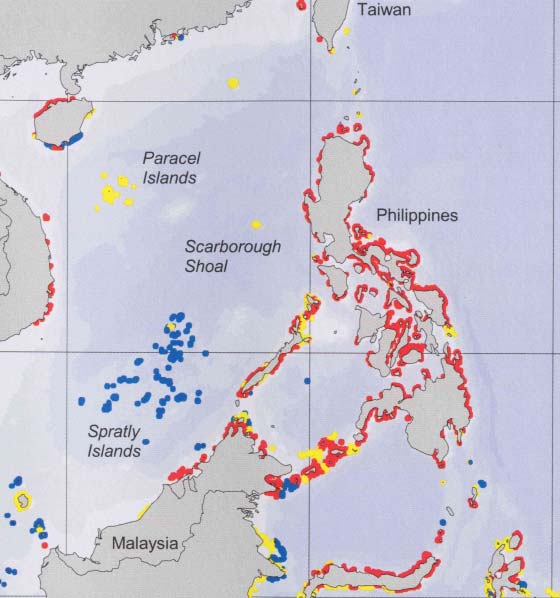

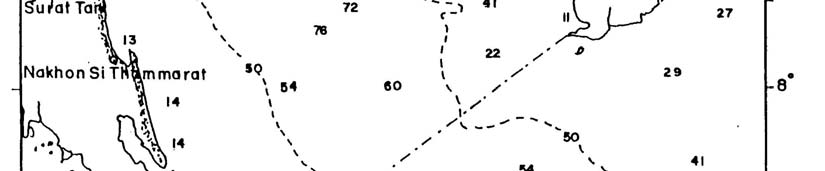

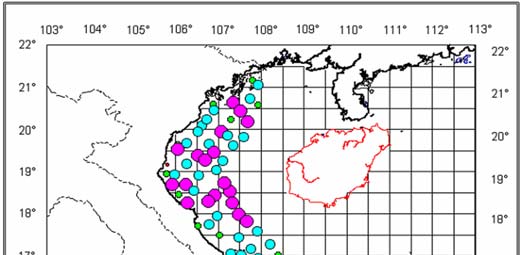

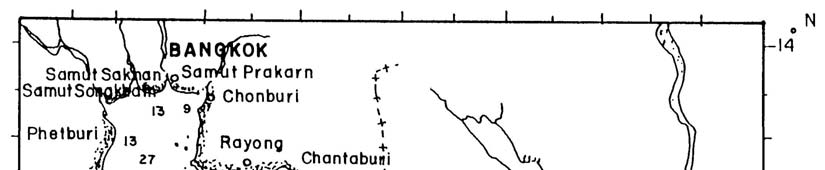

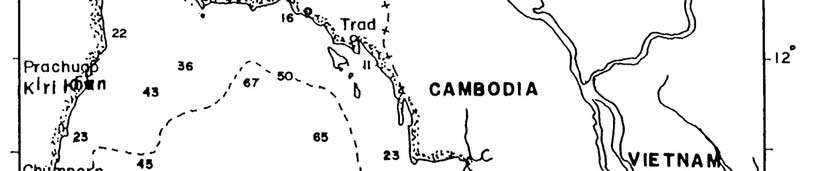

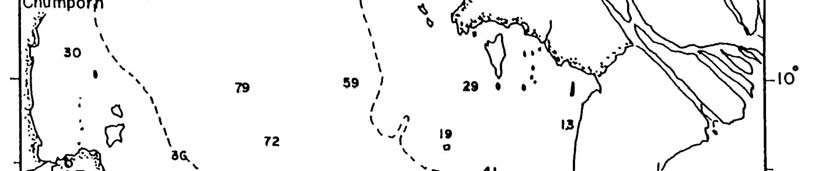

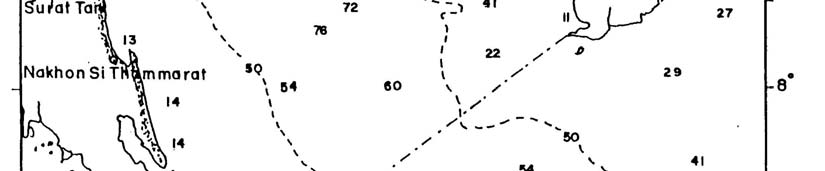

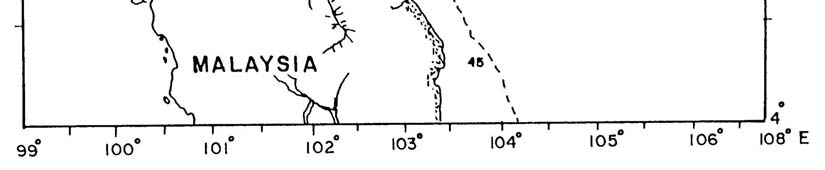

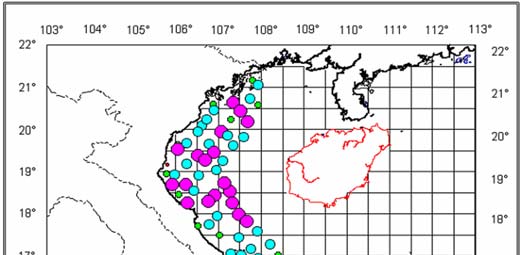

Figure 1

Map of Cambodia's Coastal Waters.

Table 1

Cambodia's fisheries production from 1990 to 2001.

(fish and shrimp unit = tonnes; and crocodile unit = heads).

Total

Inland

Marine

Aquaculture Production

Years

Production

Fisheries

Fisheries

Fishes Shrimp

Crocodile

1990 111,400 65,100 39,900 6,400

5,654

1991 117,800 74,700 36,400 6,700

6,100

1992 111,150 68,900 33,700 8,550

3,664

1993 108,900 67,900 33,100 7,400 500 4,816

1994 103,200 65,000 30,000 7,640 560 6,194

1995 112,510 72,500 30,500 8,779 731

14,691

1996 104,310 63,510 31,200 9,000 600

20,200

1997 114,600 73,000 29,800 11,534 266 17,000

1998 122,000 75,700 32,200 13,903 197 40,700

1999 284,100 231,000 38,100 14,938 62 25,380

2000 296,030 245,600 36,000 14,410 20 26,300

2001 444,500 385,000 42,000 13,682 143 36,000

(Source: DoF 2002)

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA 3

Table 2

Marine capture fisheries production in Kampot province from 1992 to 2001 (tonnes).

Low

Cepha - Slipper

Blood

Sea

Fresh-

Year Fishes Value

Shrimp Ray

Crabs Snails

Krill

Total

lopod lobster

cockle

cucum

water

Fishes

-ber

Fish

1992 1,064 1,058 993 669 296 162 1,040 1,346 1,472

- -

- 8,100

1993

654

1,134

229

678

236

156

1,020

1,465

1,507

-

861

-

7,940

1994

2,148

1,430

529

427

418

89

1,531

450

423

132

23

-

7,600

1995

2,895

2,000

625

176

310

36

900

118

180

60

-

-

7,300

1996

3,020

2,125

538

181

284

26

992

104

179

51

-

-

7,500

1997

2,974

2,045

591

167

320

28

1,120

138

172

45

-

-

7,600

1998

2,610

1,620

501

184

291

22

992

144

208

63

15

100

6,750

1999

2,720

3,025

340

135

199

7

801

104

135

34

-

-

7,500

2000

2,600

1,755

402

176

284

-

1,077

129

166

11

-

100

6,700

2001

2,703

1,786

284

165

247

-

870

176

199

-

-

100

8,100

(Source: DoF 2002)

Table 3

Marine capture fisheries production in Sihanoukville municipality from 1992 to 2001

(tonnes).

Low

Sea

Cepha

Slipper

Blood

Fresh

Year Fishes

Value Shrimp Ray

Crabs Snails

Krill

cucum-

Total

-lopod

lobster

cockle

water fish

Fishes

ber

1992

6,132

1,117

600

-

173

-

430

-

48

-

-

100

8,600

1993

6,090

1,004

641

-

146

-

428

-

56

-

-

195

8,560

1994

6,162

999

682

-

161

-

504

-

7

-

-

185

8,700

1995

5,675

1,600

820

50

225

-

610

-

38

-

-

182

9,200

1996

5,780

1,920

1,100

-

290

-

590

-

60

-

200

160

10,100

1997

4,345

3,155

1,150

-

476

-

592

-

54

-

68

160

10,000

1998

6,510

4,840

1,300

-

719

6

719

5

61

60

-

180

14,400

1999

7,295

4,455

1,570

-

1,800

40

1,080

80

150

70

-

260

16,800

2000

6,850

4,690

1,580

-

1,830

45

1,000

120

35

50

-

300

16,500

2001

6,943

4,287

1,730

-

1,496

40

897

1,236

226

210

-

535

17,600

(Source: DoF 2002)

Table 4

Marine capture fisheries production in Koh Kong province from 1992 to 2001 (tonnes).

Low

Fresh-

Cepha-

Slipper

Blood

Mantis

Year Fishes Value

Shrimp Ray

Crabs Snails

water

Total

lopod

lobster

cockle

shrimp

Fishes

fish

1992

5,560 6,485

3,000

318

791

-

700

-

146

-

-

17,000

1993

6,094 6,346

2,368

146

601

925

-

120

-

-

16,600

1994

5,093 4,845

2,395

133

487

-

612

-

135

-

-

13,700

1995

5,230 5,700

2,000

120

450

-

300

-

200

-

-

14,000

1996

5,185 4,997

2,064

110

390

-

644

-

110

-

-

13,500

1997

4,966 3,403

2,380

108

445

-

574

-

194

-

-

12,070

1998

4,020 3,600

1,840

30

510

-

520

-

180

-

-

10,700

1999

7,206 3,317

1,115

40

480

-

458

696

82

-

6

13,400

2000

5,938 3,307

815

69

498

4

1,348

26

325

10

10

12,350

2001

7,104 4,764

1,606

42

604

-

1,410

1,082

762

-

26

17,400

(Source: DoF 2002)

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

4 NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA

Table 5

Marine capture fisheries production in Kep municipality from 1996 to 2001

(tonnes).

Low

Cepha-

Slipper

Fresh-

Year Fishes Value

Shrimp Ray

Crabs

Krill

Total

lopod

lobster

water

Fishes

Fish

1996

20 - 5

- 5

-

70 -

- 100

1997

43

5

23

1

5 -

53

- -

130

1998 62 100

30 -

10

- 146 2

-

350

1999 150 70

30 -

6

- 140

-

4

400

2000

138

81

50

-

15 -

168

8 -

460

2001

123

10

42

2

8 -

285

- -

470

(Source: DoF 2002)

1.1.2 Fishing effort by gear (number of fishing days/number of boats)

Fishing Gear

Many types of small-scale or artisanal, middle-scale, and large-scale fishing gear are used in

Cambodia. According to a proclamation made by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries,

small-scale or artisanal and middle-scale fishing gears are distinguished by the capacity of boat

engines and fishing gear size. The term commercial fishery is used only for inland fisheries and is rarely

used in relation to Cambodia's marine fisheries.

Marine capture fisheries in Cambodia are divided into two categories, namely middle-scale fisheries

and small-scale or artisanal fisheries. Middle-scale fisheries are those utilising highly efficient fishing

gear and vessels with capacity to fish both offshore and inshore using a variety of gear types, with the

exception of trawling in inshore waters (Table 6). These fisheries are required to pay tax to the

government. After the government declared a reform of the fisheries sector in October 2000, middle-

scale inland fishers do not have to pay tax. However, fishers operating middle-scale fishing gears in

marine waters are required to pay tax as usual, albeit at rates lower than those prior to the government

reform.

Table 6

Commercial fishing gears used in the coastal waters of Cambodia.

Type of Fishing Gear

Type of Fishing Gear

No.

No.

English Name

Khmer name

English Name

Khmer name

1 Trawl

Uon

Ohs

7 Scomberomorus gill net

Mong Trey Beka

2

Purse seine/Ring net

Uon Tith

8

Mackerel gill net

Mong Trey Kamong

Shrimp gill net

3

Anchovy encircling seine

Uon Ka Koeum

9

Mong Bang Kear

or Trammel net

4

Beach seine

Uon Khow

10

Crab gill net

Mong Kdam

5

Encircling seine

Uon Houm

11

Horizontal longline

Santouch Ro Noung

6

Gill net

Mong Paehk

12

Clupea gill net

Mong Trey Kbork

(Source: DoF 2002)

The number of fishing gear units used in any given area varies according to the distribution and

abundance of natural resources, as well as socioeconomic and market conditions. For example,

dredging for short-neck clam began in Cambodia at the end of 1999 following identification of a market

for this species in Thailand. Similarly, the intensity of small trawl fisheries increased in 1997, leading to

serious concern for the longer-term sustainability of marine fish stocks and conflicts over resource use

between small-scale and middle-scale fishers.

The use of trawl nets, mackerel encircling seines, and short-neck clam dredges is most common in

Sihanoukville and Koh Kong as these areas have deep-water areas suitable for the use of these gear

types. In Kep and Kampot, traditional fishing gear, including gill nets, crab nets, and longlines, are more

commonly used.

Small-scale fisheries are those utilising traditional and/or passive fishing gear (Table 7), non-power

boats, or power boats with a capacity lower than 5 HP. Generally, these fisheries operate in inshore

waters up to 3 nautical miles from the shore and small-scale fishers are not required to pay tax.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA 5

Table 7

Small-scale or artisanal fishing gears used in the coastal waters of Cambodia.

No.

English Name

Khmer name

No.

English Name

Khmer name

Gill net (Mong Paehk)

1

Crab gill net

Mong Kdam

3

Fish gill net

Mong Paehk

2

Shrimp gill net

Mong Bang Kear

4

Seabass gill net

Mong Trey Spong

Stationary Gear

5

Squid trap

Lop Meuk

8

Bamboo crab trap

Lop Kdam Roeusey

6

Fish trap

Lop Trey

9

Small winged set bag

Pong Pang

7

Crab trap

Lop Kdam

10

Circular net crab trap

Lop Mong Kdam

Mobile gear

11

Push net

Thnorng Os Ky

13

Drift gill net

Mong Bandet

12 Hook

Santouch

(Source: DoF 2002)

The total number of units for all types of gear commonly used in coastal Cambodia for each year from

1992 to 2001 is shown in Table 8.

Table 8

Number of units of fishing gears used in all coastal provinces and municipalities of

Cambodia combined from 1992 to 2001.

Nº Fishing

gears

Unit 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

1

Trawl

net

Set 422 442 549 634 560 460 545 654

1,516

1,310

2

Purse

seine Set 13 14 15 16 16 15 15 8 10 10

Anchovy

3

Set 13

13 9

15

10 2 - 3 5 3

encircling seine

4

Beach

seine Set 18 19 6 6 1 26 7 20 26 21

5

Encircling

seine

Set 15 - - 6 1 26 7 7 7 2

6 Gill

net

m

65,180

8,940

6,730 29,991 31,491 13,779 6,200 190,730 231,835 325,500

7

Mackerel gill net

m

3,700

9,800

36,050 12,050 15,550 131,220 140,500 198,200 178,300 64,700

Scomberomorus

8

m 31,403

31,202

59,595 7,000 51,300 66,800 85,000 140,100 148,000 184,000

gill net

9

Shrimp gill net

m

114,705

93,450

110,950 161,486 694,563 469,100 469,050 996,055 653,890 323,200

10

Crab gill net

m

43,852

32,100

37,450

95,728 580,439 393,200 426,000 538,545 961,370 635,200

11

Clupea gill net

m

500

1,200

3,000

8,850 10,250 23,900 23,900 33,600 38,000 27,500

No.

12 Trap

60 637

2,277

1,902

26,761

23,200 23,242 33,960 51,249 66,255

trap

Horizontal

No.

13

16,000 760 920

1,950

14,620

4,750 4,750 8,600

15,360

15,600

longlines

hook

(Source: DoF 2002)

1.1.2.1 Trawl (Khmer name Uon Ohs)

Two types of trawl fishing is conducted in Cambodian waters, namely demersal otter board trawling and

pair trawling. Trawl fishing was introduced to Cambodia in 1960 and was used to target a multitude of

pelagic and demersal species (MoE 1998). Non-commercial species were usually discarded, although

following the establishment of a fishmeal factory in 1993, trawl operators have begun targeting low

value fish for use in the production of fishmeal. Low-value fish is composed of small-size fish that

previously had no value in the market, non-edible species, and juveniles of economically important

species that are unacceptable in the market. During the 1980s, catches of fish in Cambodia's trawl

fisheries contained about 30 to 40% low value fish, although low value fish now represents about 60 to

65% of the total catch.

Approximately 95% of trawl fishing vessels are single trawlers. They typically only spend one or two

days fishing inshore or offshore waters during each fishing trip. Catches of target species are typically

preserved with ice. Some commercial species are kept alive. Trawl fishing is more common in

Sihanoukville (Table 9) as this municipality has a good road (national road number 4) connection with

Phnom Penh. Furthermore, it has tourist facilities, electricity and many fish processing factories,

including the fishmeal factory discussed above. Pair-trawling has been conducted illegally in

Cambodian waters by both local and foreign fishers.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

6 NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA

Table 9

Number of trawl nets used in the coastal provinces and municipalities of

Cambodia from 1992 to 2001 (set).

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - - - - - 5 7 52

52

Kampot

31 16 5 186 186 20 30 22 89 89

Sihanoukville 227 242 276 262 244 226 296 283 656 756

Koh

Kong

164 184 268 186 130 214 214 342 719 413

Total

422 442 549 634 560 460 545 654 1,516

1,310

(Source: DoF 2002)

1.1.2.2 Purse seine/ring net (Khmer name Uon Tith)

Two types of purse seine are used in Cambodian waters. Purse seining without the use of lights is a

legal fishing method. Cambodian coastal fishers have used this gear for many years, in both shallow

water and offshore areas. The use of light luring purse seines is illegal in Cambodian waters, although

is a method used in offshore water areas of Cambodia largely by fishers from neighbouring countries.

The use of light luring purse seines in Cambodian waters is very difficult to control as fishers typically

use high-powered vessels that can easily leave Cambodian waters upon sighting Cambodian fisheries

inspection vessels. This fishing practice is legal in Thailand and Viet Nam.

Purse seines used in Cambodian waters typically have a mesh size of 1 cm. The main species caught

using this gear type are pelagic fishes such as mackerel (i.e. Rastrelliger spp.), sardines, and other

small fishes, although mackerel comprises around 80 to 90% of the total catch. Purse seines and

anchovy encircling seines are operated in the same manner but differ in mesh size.

Cambodia's purse seine fleet is based in Sihanoukville. The number of units of this gear in use has

decreased (Table 10) due to overexploitation of the target species, and the increased use of pair trawls

and light luring purse seines in the offshore waters of Cambodia. This gear type is now most commonly

used at night, and most fishers using purse seines also use other fishing gear such as trawl or gill nets.

Table 10

Number of purse seine/ring nets used in the coastal provinces and municipalities

of Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (set)

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - - - - - - - - -

Kampot

- - - - - - - - - -

Sihanoukvill

13 14 15 16 16 15 15 8 10 10

e

Koh

Kong - - - - - - - - - -

Total

13 14 15 16 16 15 15 8 10 10

(Source: DoF 2002)

Other types of seine used in Cambodian waters are listed below.

Anchovy encircling seine (Khmer name Uon Ka Koeum)

The use of anchovy encircling seines began in Cambodia during the 1960s. This gear type is used to

catch anchovy during the daytime. This gear type is mostly used by fishers based in Sihanoukville and

Koh Kong (Table 11), and is constructed using meshing similar to that of a mosquito net. Anchovy

encircling seines are now rarely used due to the declining availability of target species, and increased

prevalence of pair trawling and light luring purse seines.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA 7

Table 11

Number of anchovy encircling seine nets used in the coastal provinces and

municipalities of Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (set)

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - - - - - - - - -

Kampot

- - - 7 7 - - - - -

Sihanoukville 1 - 1 1 1 1 - 1 3 3

Koh

Kong

12 13 8 7 2 1 - 2 2 -

Total

13 13 9 15 10 2 - 3 5 3

(Source: DoF 2002)

Beach seine (Khmer name Uon Khow)

Beach seines are widely used in shallow water or along beaches. Fishers operate this gear with non-

motorised boats or pull them along sandy beaches without the assistance of hauling devices. All beach

seines used in coastal areas of Cambodia have the same design and are effective in capturing small

fishes, including anchovy, sardine, and shrimp inhabiting shallow water areas with sandy substrate.

This fishing gear is most commonly used by fishers based in Kampot province and Kep municipality

(Table 12).

Table 12

Number of beach seines used in the coastal provinces and municipalities of

Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (set)

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - - - - - 3 3 3 2

Kampot

3 19 6 - - 22 - 13 19 19

Sihanoukville

14 - - 6 1 4 - - - -

Koh

Kong

1 - - - - - 4 4 4 -

Total

18 19 6 6 1 26 7 20 26 21

(Source: DoF 2002)

Encircling seine (Khmer name Uon Houm)

Fishers use encircling seines to capture a variety of fish species. The use of this gear relies on the

deployment of an anchor lure, or a branch of a tree, to aggregate schools of fish. This fishing gear is

used infrequently in Cambodian waters and only 2 units were recorded to be in use during 2001 (Table

13).

Table 13

Number of units of encircling seine used in coastal provinces and municipalities of

Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (set)

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - - - - - 3 3 3 2

Kampot

- - - - - 22 - - - -

Sihanoukville 14 - - 6 1 4 - - - -

Koh

Kong

1 - - - - - 4 4 4 -

Total

15 - - 6 1 26 7 7 7 2

(Source: DoF 2002)

1.1.2.3 Gill net (Khmer name Mong Paehk)

Many types of gill net with various mesh sizes are used in Cambodian waters. The use of gillnets in

Cambodia is common and they are typically used in inshore water areas to target a multitude of

species. For example, drift gill nets are set just below the surface to target and catch various pelagic

species, including mackerel, barracuda, shark, and trevally. Most gill nets are set on the bottom using

anchors or heavily ballasted leadlines to target and catch a variety of demersal species. These fishing

gears are used during the night and day, largely depending on the availability of target resources.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

8 NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA

Table 14

Number of units of gill net used in the coastal provinces and municipalities of

Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (metres)

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - -

- 500 700 800 1,000 1,000 4,200

Kampot

61,055 3,940 2,780 27,091 27,091 9,479 1,800 1,800 1,800 20,900

Sihanoukville 4,125 3,200

3,950 2,900 3,900 3,600 3,600 49,100 41,900 50,400

Koh

Kong

- 1,800

-

-

-

-

- 138,830 187,135 250,000

Total

65,180 8,940 6,730 29,991 31,491 13,779 6,200 190,730 231,835 325,500

(Source: DoF 2002)

Species-specific gill nets are also used in Cambodian waters. These fishing gear are typically named

according to the species they are used to target.

Mackerel gill net (Khmer name Mong Trey Kamong)

This fishing gear is designed to catch pelagic species, including mackerel, which represents more than

80 to 90% of the total catch in this gear. Article 27 of Cambodia's Fisheries Law (in Khmer called Kret

Chhbab Lek 33 Kra. Chor), enacted on 9 March 1987, prohibits the fishing for mackerel from 15

January to 31 March each year, as it is believed this is the period in which mackerel spawn. Most

fishers use more than one gear type, enabling them to target other species during the closed season for

mackerel. Mackerel gill nets are mainly used by fishers based in Sihanoukville municipality and Koh

Kong province (Table 15).

Table 15

Number of units of mackerel gill net used in coastal provinces and municipalities

of Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (metres)

Province/

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

-

-

-

-

- - - - -

-

Kampot

-

-

9,450

-

- - - - -

-

Sihanoukville 3,700

9,800

26,600

12,050

15,550 17,620 26,900 84,600 64,700

64,700

Koh

Kong

-

-

-

-

- 113,600 113,600 113,600 113,600

-

Total

3,700 9,800 36,050 12,050 15,550 131,220 140,500 198,200 178,300 64,700

(Source: DoF 2002)

Scomberomorus gill net (Khmer name Mong Trey Beka )

This type of gill net is widely used in Sihanoukville municipality and Koh Kong province (Table 16).

Single fishing boats use between 1 to 10km of net, depending on the size of the boat. The nets used by

smaller vessels (10-90 HP) are approximately 9 m in depth, whilst those used by larger vessels (>90

HP) range between 9 and 18 m in depth. Scomberomorus gill nets are set on the seafloor to target and

catch various pelagic fish species. The main species caught by this gill net type are Scomberomorus

spp., scads, and sharks.

Table 16

Number of units of Scomberomorus gill net used in the coastal provinces and

municipalities of Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (metres)

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - - - - - -

-

- -

Kampot

-

-

- 1,200 1,200

- 8,700

-

-

-

Sihanoukville

29,600 30,000 44,700 46,600 50,100 43,800 45,800

86,600 100,000 100,000

Koh

Kong

1,800 1,200 14,895 1,200 32,100 23,000 30,500

53,500

48,000 84,000

Total

31,400 31,200 59,595 7,000 83,400 66,800 85,000 140,100 148,000 184,000

(Source: DoF 2002)

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA 9

Shrimp gill net or Trammel net (Khmer name Mong Bang Kear)

Trammel nets are widely used throughout Cambodian waters and most commonly in Sihanoukville and

Koh Kong province (Table 17). This gear type consists of two or three panels of netting of different

mesh sizes. In a trammel net with three panels, the two outer panels typically have a mesh size of 8 to

10 cm, whilst the inner panel has a 3.8 to 4.2cm mesh size. Fishers use trammel nets to target and

catch a variety of demersal species of all shapes and sizes, as this gear type is most often set on the

seafloor and is not selective for fish size or shape. Trammel nets are considered highly effective fishing

gear for shrimp, catfish, and silver and black pomfrets.

Table 17

Number of units of shrimp gill net or trammel net used in the coastal provinces and

municipalities of Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (metres)

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995

1996

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

200

300

1,000

1,000

2,000

1,200

Kampot

9,775 4,050 1,600 13,143

13,143

10,500

9,750 4,100

4,100 27,100

Sihanoukville

102,905 86,800 109,350 135,200

168,700

145,700

145,700

121,900

104,900 104,900

Koh Kong

2,025 2,600

13,143

512,520

312,600

312,600 869,055

542,890 190,000

Total

114,705 93,450 110,950 161,486

694,563

469,100

469,050 996,055

653,890 323,200

(Source: DoF 2002)

Crab gill net (Khmer name Mong Kdam)

This is another type of gill net constructed with various mesh sizes and sufficient ballast to enable it to

be set on the seafloor of inshore water areas. Mesh sizes used range from 4 to 10cm depending on

water depth or fishing area. Nets used in shallow water areas have mesh sizes from 4 to 8 cm and 80%

of the nets have a mesh size of 6cm. Approximately 80 to 95% of total catches in this net type is

swimming crab (Portunis pelagicus). For deeper inshore waters, a mesh size of 8-10 cm is used and 80

to 90% of the catch is crab. The length of crab gill nets used in coastal areas is shown in Table 18.

Table 18

Number of units of crab net used in coastal provinces and municipalities of

Cambodia from 1992 to 2001. (metres)

Province/

1992

1993

1994

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

300

500 20,000 10,000 10,000 10,000

Kampot

34,042

11,500

21,450 30,364 30,364 10,900 24,200 40,755 27,600 27,600

Sihanoukville

7,450

18,000

16,000 35,000 38,500 87,500 87,500 219,500 204,000 225,000

Koh

Kong

2,360 2,600

30,364 511,275 294,300 294,300 268,290 719,770 372,600

Total

43,852

32,100

37,450 95,728 580,439 393,200 426,000 538,545 961,370 635,200

(Source: DoF 2002)

Clupea gill net (Khmer name Mong Trey Kbork)

This is yet another type of gill net constructed with various mesh sizes for use in shallow or inshore

waters. It has a mesh size of 3.5cm and is used to capture demersal and pelagic fishes, especially

Clupea spp.. Single small-scale fishing boats carry 150 to 200m of this gill net and it is used throughout

the year, mainly by fishers based in Sihanoukville municipality (Table 19).

Table 19 Number of units of Clupea gill net used in coastal provinces and municipalities of

Cambodia from 1992 to 2001 (metres).

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

2,500

Kampot

5,700

7,600

7,600

Sihanoukville

400 1,200 3,000 8,850 10,250 15,900 15,900 19,900 19,900

19,900

Koh

Kong 100

8,000

8,000

8,000

8,000

Total

500 1,200

3,000

8,850

10,250

23,900

23,900

33,600 38,000

27,500

(Source: DoF 2002)

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

10 NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA

1.1.2.4 Other (push nets, trolling, hand line, long line, trap)

Push nets (Khmer name Chhep Yun)

Push nets are recognised as a destructive fishing gear and it is prohibited to deploy this gear using an

engine-powered vessel in Cambodia. Despite this, the illegal use of push nets is widespread. Push nets

usually have a mesh size smaller than 1 cm, and are unselective in terms of the size and species of fish

caught. The use of push nets in areas of sensitive habitat areas is thought to be a key contributing

factor to seagrass loss in Cambodia.

Traps (Khmer name Lop)

There are many types of traps used in Cambodian waters. They are constructed from different types of

material. For example, crab traps (Khmer name Lop Kdarm), previously made from bamboo and very

big, are now made from netting and are collapsible. This enables a single fisher to use more than 100

traps. Bamboo fish traps (Khmer name Lop Trey) are also commonly used. This gear type is

constructed in a variety of sizes and is used in conjunction with a bamboo-fender.

Octopus and squid traps (Khmer name Lop Meuk) are used widely in Cambodia, and bamboo framed

octopus and squid traps are common small-scale fishing gear. In some areas fishers have begun

covering trap frames with netting in order to catch fish. The data recorded by the DoF does not

differentiate between trap types (Table 20).

Table 20

The number of traps (crab trap, squid trap and fish trap combined) used in the

coastal provinces and municipalities of Cambodia from 1992 to 2001.

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - -

- 100 200

1,000 500

11,550

10,000

Kampot

-

- 997 151 151 2,303 1,745 1,745 1,745 6,175

Sihanoukville

- 320 1,280 1,600 1,450 1,620 1,420 2,300 2,080 2,080

Koh

Kong

60 317

151 25,060 19,077 19,077 29,415 35,874 48,000

Total

60

637

2,277

1,902

26,761

23,200

23,242

33,960 51,249 66,255

(Source: DoF 2002)

Horizontal longlines (Khmer name Santouch Ro Noung)

This is the simplest of fishing gear and requires only a line and a baited hook. The line is equipped with

hooks, which may be single or multiple, big or small, depending on the species desired. Horizontal

longlines are commonly used in Sihanoukville and Koh Kong (Table 21).

Table 21

Number of units of horizontal longlines used in the coastal provinces and

municipalities of Cambodia from 1992 to 2001 (hooks).

Province/

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Municipality

Kep

- - - - - - - - - -

Kampot

- - - - - - - - - -

Sihanoukville

- 750 590 1,950 1,650 1,450 1,450 7,500 14,150 14,300

Koh

Kong

16,000

10 330

12,970 3,300 3,300 1,100 1,210 1,300

Total

16,000

760

920

1,950

14,620

4,750

4,750

8,600 15,360 15,600

(Source: DoF 2002)

Ranking by type of fishing gear

The relative importance of fishing gear types to fishing communities and fish production has not been

investigated in Cambodia. The Coastal Zone Management Project ranked major species by specific

fishing gears (Table 22).

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA 11

Table 22

The species targeted by different fishing gears in Cambodia.

Fishing gear

Target group

Secondary group

English Name

Khmer Name

Rastrelliger kanagurta,

Mong Trey

Mackerel gill net

Rastrelliger brachysoma

Megalaspis cordyla, Thunnus

Kamong

tonggol

Anchovy encircling

Uon Ka Koeum

Stolephorus indicus

seine

Shrimp gill net

Mong Bang Kear

Penaeus merguiensis

Scomberomorus guttatus, Thannus

Serranidae, Lutjajisdae,

thannus, Ariidae thalassinus,

Nemipteridae, Sciaenidae,

Eleuteronema tetradactilum, Liza

Drepanidae, Siganidae,

Fish gill net

Mong Trey

argentea, Valamugil ceheli, Rastrelliger

Trichiuridae, Stromatoidae,

brachysoma, Rastrelliger kanagurta,

Chirocentridae and

Megalaspis cordyla, Formio niger, Lates

Synodontidae.

calcarifer, Dasyatidae

Crab gill net

Mong Kdam

Portunus spp., Scylla serrata

Crab trap

LopKdam

Portunus spp., Scylla serrata

Squid trap

Lop Meuk

Sepioteuthis lessoniana, Loligo spp.

Fish stake trap

Mixed fish species

Santouch Ro

Orectolobidae, Carcharinidae,

Horizontal longline

Noung

Dasyatidae, Serranidae, Lutjanidae

Mixed fish, Metapenaeus spp.

Push net

Chhep Yun

Sepiolidae, Octopus spp.

Chhneang os

Shellfish dredge

Arcidae, Veneridae

khchorng

Beach seine net

Uon Khow

Mixed fish, Sepiolidae, Loligo spp.

Note: For common names of the species mentioned in Table 22 see Table 28.

(Source: MoE 1996)

Fishing vessel effort

The number of fishing vessels in Cambodian waters fluctuates according to the distribution and

abundance of natural resources and broader socioeconomic, market and political conditions.

Unfortunately, existing data does not enable the estimation of the number of fishing vessels by the

different types of fishing gears used. This is because each fishing vessel may operate more than one

type of fishing gear and they change the type of gear used according to the season. The number of

fishing vessels by coastal province and municipality is summarised in Tables 23 to 26.

Table 23

Number of marine fishing vessels in Kampot province, Cambodia.

Boats without

Boats with engines

engines and

Year

less than 5T

<10 HP

10-30 HP

30-50 HP

>50 HP

Total

Number Stock Unit

HP Unit HP Unit

HP

Unit HP Unit HP

1992 200 - - -

227

-

-

-

-

-

227 -

1993 100

0.2-0.5 64 227

35

560

-

-

2

460 101

1,247

1994 110 -

60 -

23

-

-

-

-

-

83 -

1995 - - - -

-

-

-

-

-

- - -

1996 100 -

50 -

30

-

25

-

-

-

105 -

1997 110

50 -

30

-

25

-

-

-

105 -

1998 110 110 119 810

102

1,408

-

-

-

- 221

2,218

1999 120

- 67 392

111

1,471

-

-

-

- 178

1,863

2000 136

- 67 392

111

1,471

-

-

-

- 178

1,863

2001 133 66 151 823

252

3,379

1

40

12

1,154 416

5,396

(Source: DoF 2002)

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

12 NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA

Table 24

Number of marine fishing vessels in Sihanoukville municipality, Cambodia.

Boats without

Marine boats with engines

engines and

Year

less than 5T

<10 HP

10-30 HP

30-50 HP

>50 HP

Total

Number

Stock

Unit HP Unit HP Unit HP Unit HP Unit HP

1992 432 - - -

720

-

187

-

- -

907

-

1993 452

0.2-0.5 - -

552

52,274

163

25,273

- -

715

77,547

1994 391 - - -

656

-

177

-

- -

833

-

1995 423 - - -

646

5,900

174

27,580

- -

820

33,480

1996 180 - - -

692

6,720

167

26,211

- -

859

32,931

1997 310 - - -

654

7,265

150

24,249

- -

804

31,514

1998

237 47 198

1,208 467

6,043

23

875

162

26,630 850

34,756

1999

- - - -

855

10,736

245

34,928

- -

1,100

45,664

2000

-

- 144 894 727

10,111

33

1,223

266

37,417

1,170

49,645

2001

286 57 167

1,054 809

11,503

33

1,223

269

37,415

1,278

51,195

(Source: DoF 2002)

Table 25

Number of marine fishing vessels in Koh Kong province, Cambodia.

Boats without

Marine boats with engines

engines

Year

and less than 5T

<10 HP

10-30 HP

30-50 HP

>50 HP

Total

Number

Stock

Unit HP Unit HP

Unit

HP Unit HP Unit HP

1992

- -

- -

215

1,076

-

-

178

27,765

393 28,841

1993 330

0.2-0.5

1,018

4,120

14

348

87

6,142

111

24,551

1,230 35,161

1994 245 -

1,207 -

26

-

96

-

182

60,200

1,511 60,200

1995 -

-

260

1,820

12

237

71

5,567

138

29,752

481 37,376

1996 2,932 -

282

2,138

132

3,460

8

356

156

26,158

578 32,112

1997 71

-

2,110

22,495

311

6,097

31

1,275

140

18,855

2,592 48,722

1998 71 -

2,110 -

311

-

31

-

140

-

2,592 -

1999 -

-

1,622

9,759

562

7,921

34

1,240

225

35,972

2,443 54,892

2000 19

-

2,787

17,902

406

5,658

32

1,410

271

31,390

3,496 56,360

2001 71

-

2,518

14,723

597

8,446

93

2,920

217

25,861

3,425 51,950

(Source: DoF 2002)

Table 26

Number of marine fishing vessels in Kep municipality, Cambodia.

Boats without

Marine boats with engines

engines and

Year

less than 5T

<10 HP

10-30 HP

30-50 HP

>50 HP

Total

Number Stock Unit HP Unit HP Unit HP Unit HP Unit HP

1996 100 -

60

320

-

-

-

-

-

-

60 320

1997 110 -

60

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

60 -

1998 110

110

61

305

8

116

-

-

-

-

69 421

1999 120 -

60

300

4

60

-

-

-

-

64 360

2000 136 -

135

675

58

870

-

-

-

-

193 1,545

2001 133

66

140

700

52

780

-

-

-

-

192 1,480

(Source: DoF 2002)

1.1.3 Economic value of catch (estimated or actual)

According to the marine fisheries statistics in Table 1, as well as a survey by Tana and Todd (2002), it

can be estimated that the total volume of marine capture fisheries production in Cambodia is between

30,000 to 50,000 tonnes per year.

Seafood from Cambodia is exported to several countries in South-east Asia, including China, Thailand,

Viet Nam, and Singapore. Thus far, many kinds of seafood have been exported (Table 27).

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA 13

Approximately 15 to 25% of the total marine catch is exported annually. It should be noted that these

exports are almost exclusively unprocessed (live or chilled) products.

Table 27

Volume and values of marine fishery product exports from Cambodia in 2000.

Export

Items

volume

Total cost (US$)

Total export value (US$)

Value added (US$)

(tonnes)

Chilled shrimp meat

500

625,000

875,000 - 1,000,000

250,000 - 375,000

Chilled crab meat

500

1,500,000

2,250,000

750,000

Frozen pealed shrimp

320

2,400,000

3,000,000

600,000

Frozen squid/octopus

140

140,000

250,000

110,000

Live ornamental fish

10

19,000 - 20,000

29,000 - 31,200

10,000 - 11,200

Live mantis shrimp

10

44,000

66,000

22,000

Live short neck clam

5,000

1,250,000 - 1,500,000

2,500,000 - 2,750,000

1,000,000 - 1,250,000

Live blood cockle spat

500

220,000

475,000

255,000

Dried seaweed

120

50,000

72,000

22,000

Total

7,100

6,250,000 - 6,500,000

9,500,000 - 9,900,000

4,770,000 - 5,420,000

Note: Export values expressed as Free on Board (F.O.B.).

(Source: Tana and Todd 2002)

1.1.4 Importance of the fisheries sector in terms of employment and dependence

The coastal population of Cambodia is approximately 1 million people. Estimates of the number of

people involved in coastal and marine fisheries differ widely. One estimate is that about 40% of the

coastal population are full-time fishers and 30% are part-time fishers. Another estimate is that only 10%

of the coastal population is involved in fisheries, including processing and marketing. The majority of

fishers are operating on the small-scale or subsistence level, and these fishers do not need to be

licensed. Moreover, the majority of fisher households also have small farming plots. The civil war and

the Khmer Rouge regime severely disrupted the traditional fishing community system in Cambodia.

During this period, coastal and marine fisheries were almost completely abandoned and only rice

farming was encouraged. In recent years, there has been a significant migration of poor people from

inland rural areas to the coast. These people mostly engage in fisheries because it requires little

investment and is open access, although they typically have no experience in marine fisheries.

Information regarding the socioeconomic dependence of Cambodians on marine fisheries is scarce. In

terms of income, people in the coastal provinces have average per capita incomes slightly below the

national average of US$21 per month and somewhat above the average for the rural population

(Ministry of Planning 1999). Most households obtain income from more than one occupation, and there

are no estimates of the number of households with fishing as their main source of income.

Cambodian people traditionally prefer freshwater fish to seafood. This is true even in the coastal areas.

It has been estimated that only about 20% of products from marine capture fisheries are used for local

consumption. The shrimp fishery developed rapidly after 1981, but declined dramatically during the

1990s. Most shrimp fishers changed from using trawl nets to gill nets, although catches are continuing

to decline. Due to a lack of infrastructure and the taxation system, a large part of the marine catch in

Koh Kong province is (illegally, and hence unrecorded) exported directly to Thailand. There are very

few facilities for processing of seafood and, with the exception of a Hong Kong based company

operating a factory in Sihanoukville for production and export of frozen shrimp, most are operating on a

small scale. The shrimp factory only operates during the shrimp season. It has about 100 local

employees, mostly women. Other industries include fish-sauce production and processing of steamed

mackerels. There is also a fishmeal factory in Sihanoukville, which produces fishmeal from dried trash

fish, and most of the employees are women.

The Cambodian fishing fleet is generally low technology, and most vessels operate only in inshore

waters on one-day trips. In addition, they use only ice for storing the catch. Interest from foreign and

local private investors in Cambodia's fisheries has mostly focused on freshwater fisheries, due to the

importance and value assigned to this sector. There is very little private sector investment in

Cambodia's marine fisheries, with most vessels operated by the owner and a hired crew.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

14 NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA

A social survey in Kampot province found that from among 26 fishing communities, 70% of 7,001

households were involved in marine fishing. Those families could earn an average monthly income of

US$25 to 30 from fishing, and a maximum of US$64, depending on their ability, capacity, and financial

resources. Incomes are better for fishing communities in Sihanoukville and Koh Kong than those of the

Kampot social survey group, due to the availability of wider and more productive fishing grounds (Tana

and Todd 2002).

2.

SPECIES OF REGIONAL, GLOBAL AND/OR TRANSBOUNDARY SIGNIFICANCE

According to the fisheries statistics collected from provincial and municipal Fisheries Offices and the

DoF, catches are not sorted by species, although some species are sorted by higher taxon. Therefore,

it is difficult to identify trends relating to species of transboundary significance and effects of exploitation

and management. Based on existing data and information collected by the DoF, it may be concluded

that Cambodian waters are characterised by high levels of species diversity, and that this diversity is

similar to that observed for marine areas of other regional countries.

According to Tana (1999), Cambodia's commercially important fish species include about 30 species

from the Mackerel, Scad, Anchovy and Snapper groups. Those species are abundant from September

to January, whereas the peak period for Penaeus and Metapenaeus shrimps is May-August. Blue

swimming crab, squid and cuttlefish are available throughout the year. There is a diverse range of

important mollusc species in Cambodia, and the most important commercial species, such as green

mussel and oysters are mainly found in the Koh Kong estuary. Blood cockle is abundant in Thmar Sar

of Kampong Som Bay and Trapeang Ropov of Kampot Bay. Marine mammals and reptiles, including

dugong, sea turtles and dolphins, also inhabit Cambodian waters. Dugong is usually found in sea grass

beds of Kampot bay from November to December, whilst a variety of dolphin species are present

throughout the year within the region. Sea turtles, especially Hawksbill, Green, and Loggerhead turtles

are observed in inshore waters adjacent to nesting beaches.

2.1

Ranking of Importance in Terms of Landings, Value, Status and Food Security

2.1.1 Landings

As mentioned previously, data on landings is not broken down by species or species group. The total

catch has been broken down by province as shown in Tables 2 to 5. It is very difficult to make any

inferences from these data as the changes may reflect changes in effort and market demand, rather

than changes in stock availability. For example, catch of low value fish in Koh Kong province decreased

drastically in the 1990s, whereas it increased in the other provinces. This probably coincided with the

collapse of shrimp farming in Koh Kong and the declining catches may not be indicative of localised

depletion of finfish stocks in Koh Kong. Overall, finfish rank highest, followed by low-value fish, shrimps,

cephalopods, and crabs.

2.1.2 Local Market Value (local currency, year)

Informal surveys of market prices for marine fishes, crustaceans and molluscs (Table 28) have provided

values in the range of 1,000-28,000 Riels per kg for fish species, and 500-50,000 Riels per kg for

invertebrates (3,800 Riels = 1 US$). These prices only cover species used for human consumption.

Given that up to 60% of the catch is low-value fish, and further assuming an average price for edible

species of US$1 per kg, the total value of the annual marine catch is estimated at US$15 to 30 million.

This value does not include the returns for fisheries products landed outside the country (illegally) nor

the value to the subsistence or artisanal sector.

Only a few species of fish, molluscs, and crustaceans have high value in the domestic market. The

domestic market for reef fish, especially groupers, is very strong. Reef fish are also an important export

commodity. As such, reef fish catches have grown rapidly in Cambodia. Price for reef fish in

Cambodia's domestic markets is responsive to market conditions in Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand,

Taiwan, and Japan, as these countries represent the major export markets for Cambodian seafood.

Field studies conducted in Sihanoukville municipality by Jensen & Try (2002) found over 21 fish

species, 12 bivalve species, 7 gastropod species, 10 crab species, and 1 horseshoe crab species with

high value in the domestic market (Table 28). Among the molluscs and crustaceans, cephalopods,

short-neck clam, shrimp, mantis shrimp, mud crab and swimming crab are the most valuable products

domestically, as local price is responsive to price for these products in international markets.

International demand and price for these products continues to grow.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

NATIONAL REPORT ON FISHERIES CAMBODIA 15

Table 28 The marine fishery resources of high value in the Psar Loeur Market, Sihanoukville,

Cambodia in 2002. (Approximate Exchange Rate: 3850 Riel/USD)

Fishes

Price

No.

Scientific name

Common name

Khmer name

(Riel/Kg)

1

Cromileptes altivelis (Valenciennes, 1828)

Humphack grouper

Trey Tok Ke Chrouk

24,000-28,000

2

Pomacanthus annularis (Bloch, 1787)

Bluering angelfish

Trey Me Ham Boa

23,000-25,000

3

Epinephelus coioides (Hamilton, 1822)

Orangespotted grouper

Trey Tok Ke Koa

22,000-28,000

4

Pampus argenteus (Euphrasen, 1788)

Silver pomfret

Trey Chab Sor

20,000-26,000

5

Epinephelus faciatus (Forsskål, 1775)

Blacktip grouper

Trey Tok Ke Kra horm

18,000-20,000

6

Plectropomus oligocanthus (Bleeker, 1854)

Highfin grouper

Trey Tok Ke Uch Kiev

18,000-25,000

7

Epinephelus quoyanus (Valenciennes, 1830)

Longfin grouper

Trey Tok Ke Para

11,000-16,000

8

Diagramma pictum (Thumberg, 1792)

Yellowdot sweetlips

Trey Ka chii

10,000-15,000

9

Pampus chinensis (Euphrasen, 1788)

Chinese silver pomfret

Trey Chab Khmao

4,000-6,000

10

Atelomycterus marmotatus (Bennett, 1830)

Coral catshark

Trey Chhlam Khla

2,000-3,000

11

Chiloscyllium punetatum Müller & Henle, 1838

Brown-banded catshark

Trey Chham Chhmar

2,000-3,000

12

Scarus quoyi Valenciennes, 1840

Quoy's parrotfish

Trey Sek Khiev

2,000-2,500

13

Himantura imbricata (Bloch & Schneider, 1801)

Scaly whipray

Trey Bor Bel

1,500-2,000

14

Sargocentron rubrum (Forsskål, 1775)

Redcoat

Trey Kror horm sraka tom

1,500-2,000

15

Strabozebrians cancellatus (McCulloch, 1916)

Harrowed Sole

Trey An Dat Chhek

1,500-2,500

16

Siganus virgatus (Valenciennes,)

Doublebarred spinefoot

Trey Korn Taing Tmor

1,500-2,200

17

Cephalopholis formosa (Shaw & Nodder, 1812)

Bluefined grouper

Trey Tok Ke Kroeum

1,300-1,800

18

Diploprion bifaciatum Kuhl & Van Hasselt, 1828

Yellow emperor

Trey Sek Loeung

1,100-1,500

19

Siganus argenteus (Quoy & Gaimard, 1825)

Silver spinefoot

Trey Korn Tang Pe

1,100-1,500

20

Siganus canaliculatus (Park, 1797)

Whitespotted spinefoot

Trey Korn Tang Kro Ub

1,100-1,500

21

Siganus guttatus (Bloch, 1727)

Goldenspotted spinefoot

Trey Korn Tang Phoeung

1,100-1,500

(Source: Jensen and Try 2002)

Bivalves

Price

No.

Scientific name

Common name

Khmer name

(Riel/Kg)

1

Anadara nodifera (Martens, 1860)

Nodular ark

Kreng Chhiem

1,800-3,000

2

Amusium pleuronectes (Linnaeus, 1758)

Asian moon scallop

Khchorng plate

1,800-2,500

3

Meretrix lyrata (Sowerby, 1851)

Lyrate hard clam

Kreng Sor

1,500-2,500

4

Paphia undulata (Born, 1778)

Undulate venus

Krum Kror Lar Hol

1,500-2,500

5

Scapharca inaequivalvis (Bruquière, 1789) Inequivalve ark

Kreng Chheim Meat Viech

1,500-2,500

6

Anadara binakayanensis (Faustino, 1932)

Globose ark

Kreng Chheim Mor Mis

1,500-2,500

7

Pteria penguin (Röding, 1798)

Penguin wing oyster

Krum se

1,500-2,000

8

Pinna bicolor Gmelin, 1791

Bicolor pen shell

Krum Chorb Chik

1,500-2,000

9

Meretrix lusoria (Röding, 1798)

Poker-chip venus

Ngeiv Hol

1,000-2,000

10

Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Green mussel

Krum Cham Puch Tea

500-1,000

11

Donax cuneatus Linnaeus, 1758

Cradle or cuneate donax

Ngeav Sor

500-1,500

12

Polymesoda erosa (Solander, 1786)

Common geloina

Ngeav Puok

500-1,500

(Source: Jensen and Try 2002)

Gastropods

Price

No.

Scientific name

Common name

Khmer name

(Riel/individual)

1

Turbo marmoratus Linnaeus, 1758

Green Turbo or Green snail

Khchorng Prak

15,000-30,000

2

Haliotis asinina Linnaeus, 1758

Donkey's ear abalone

Khchorng Pav Hoeur Vieng

7,000-10,000

3

Haliotis ovina Gmelin, 1791

Oval abalone

Khchorng Pav Joeur Khey

7,000-10,000

4

Turbo petholatus Linnaeus, 1758

Tapestry turban

Khchorng Kror La Proum

3,000-6,000

5

Strombus canarium Linnaeus, 1758 Dog conch

Khchorng Choeung Muoy

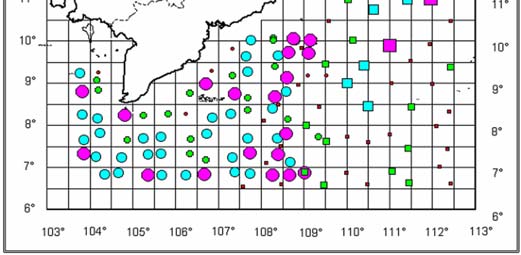

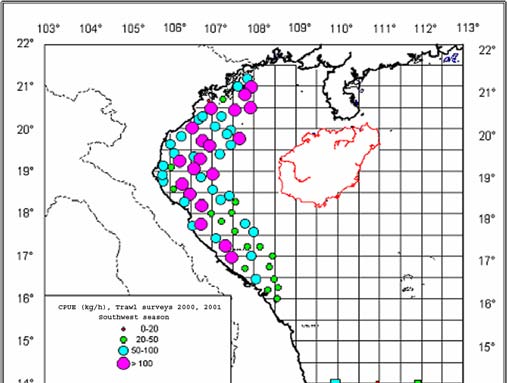

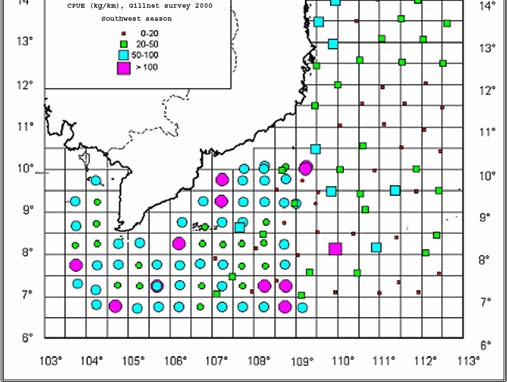

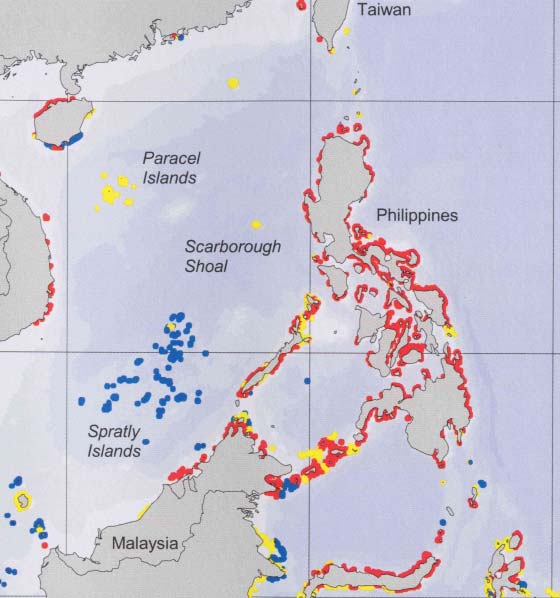

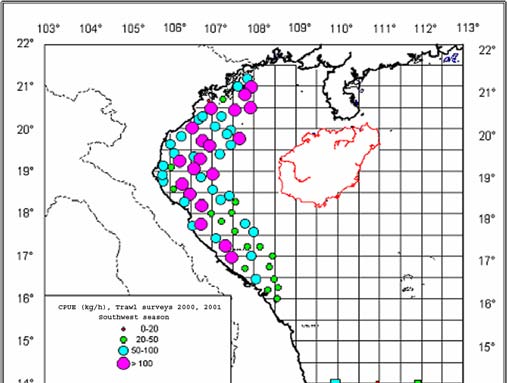

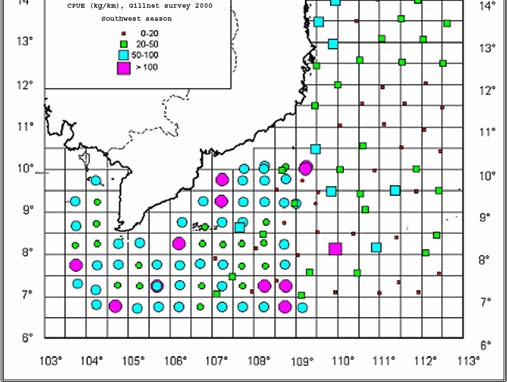

2,000-4,000