"Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends

in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand"

MANGROVES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

UNEP/GEF

Regional Working Group on Mangroves

First published in Bangkok, Thailand in 2004 by the United Nations Environment Programme.

Copyright © 2004, United Nations Environment Programme

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes

without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP

would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.

No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose without prior permission in

writing from the United Nations Environment Programme.

UNEP/GEF Project Co-ordinating Unit, United Nations Environment Programme,

UN Building, 9th Floor Block A, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand.

Tel.

+66 2 288 1886

Fax.

+66 2 288 1094

http://www.unepscs.org

DISCLAIMER:

The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of UNEP or the GEF. The

designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part

of UNEP, of the GEF, or of any cooperating organisation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city

or area, of its authorities, or of the delineation of its territories or boundaries .

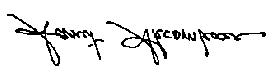

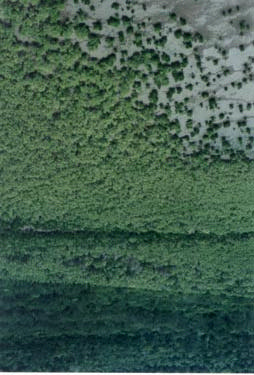

Cover Photo:

Mangroves in Xhan Thuy, Ramsar site, Viet Nam - Professor Nguyen Hoang Tri.

Photo credits:

Page 4

Prop Roots of Rhizophera - Ke Vongwattana & Sok Vong

Pneumatophores of Sonneratia. Propagules of Rhizophore Mucronata - Sonjai Havanond

Page 6

Mangrove zonation at Teluk Bintuni, Papua, Indonesia - Nyoto Santoso

Page 7

Molluscs from mangrove and tidal flats on sale in South Viet Nam - Unchalee Kattachan

Page 8

Oyster culture in front of mangroves Fanchenggang, China, & Pearl farming in Southern China -

Hangqing Fan

Page 9

Replanted Mangrove, Trad Province, Thailand - John Pernetta

Page 10

Community managed mangroves, Trad Province, Thailand - John Pernetta

Page 11

Mangrove propagules prepared for planting, Trad Province, Thailand - John Pernetta

Authors:

Professor Gong Wooi Khoon, Professor Sanit Aksornkoae, Professor Nguyen Hoang Tri, Mr. Ke Vongwattana,

Dr. Hangqing Fan, Mr. Nyoto Santoso, Mr. Florendo Barangan, Dr. Sonjai Havanond, Dr. Do Dinh Sam, and

Dr. John Pernetta.

This publication has been compiled as a collaborative document of the Regional Working Group on Mangroves of

the UNEP/GEF Project entitled "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of

Thailand."

For citation purposes this document may be cited as:

UNEP. 2004. Mangroves in the South China Sea. UNEP/GEF/SCS Technical Publication No. 1.

MANGROVES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A 1

FOREWORD

The characteristic vegetation of tropical shorelines

is mangrove, a habitat, which has been under-

valued in the past and consequently has been

subject to extensive removal and degradation in the

Southeast Asian Region.

The extensive conversion of mangrove in the

countries bordering the South China Sea during the

sixties and seventies often reflected short term

economic opportunities that benefited a few

individuals and neglected the longer term and more

widely felt, but poorly understood benefits derived

from mangrove services such as coastal protection.

Awareness of the importance of mangroves in

Southeast Asia was increased during the 1980s by

the UNESCO supported COMAR programme that

mobilised and enhanced national capacity to

undertake scientific studies of the mangrove habitat.

This programme significantly increased not only our

scientific understanding of this important habitat but

also increased both public and decision makers

awareness of the goods and services provided by

mangrove vegetation and the animals that depend

upon them.

Emeritus Professor Sanit Aksornkoae

One outcome of this UNESCO Programme was the

formation of the International Society for Ma ngrove

One such cause is our inability to value adequately

Ecosystems (ISME), which supports and promotes

in economic terms the goods and services provided

international networking and activities designed to

by mangroves. Since we cannot place a dollar value

promote the study and understanding of mangrove

on the resources we are unable to provide adequate

systems.

economic arguments to convince planners and

developers that the longer term economic benefits

The UNEP/GEF project "Reversing Environmental

of sustainably using our mangrove systems

Degradation of the South China Sea and Gulf of

outweigh the short term economic benefit of their

Thailand builds upon this foundation of regional

removal. The challenge for this project is to address

capacity in attempting to address the continuing

this scientific and information failure.

trends of degradation of mangrove systems. This

project builds not only on the existing knowledge

I am pleased to have been asked to write the

base but also on the human capacity in the

foreword to this booklet which represents the first

countries of the region. Most of the members of the

collective output from the Regional Working Group

Regional Working Group on mangroves received

on Mangroves, and which has been compiled as

training and experience through this UNESCO

background to next phase of project implementation

Programme.

when demonstration activities will be undertaken. As

such it puts into a wider, global perspective the

The support of the United Nations Environment

importance of the mangroves of this region and

Programme and the Global Environment Facility to

hence the need for concrete action. Determining the

this project is timely. Even with an increased

priority that individual national actions have from a

understanding of the importance of mangrove goods

regional perspective has been a significant task for

and services we have been unable to reverse the

the Regional Working Group on mangroves and

trend of loss and degradation at a regional scale.

one, which has served to strengthen collaboration

Although the rate of loss has declined in some

between the focal points from each country. I look

countries around the South China Sea it remains

forward to seeing the outcomes of this initial

alarmingly high given the global significance of this

collaboration.

region for the diversity of plants and animals that

mangroves support.

The UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project is unique,

firstly in being the first programme to which all the

countries bordering the South China Sea have

Professor Sanit Aksornkoae, President

agreed to implement co-operatively. Secondly this

Thailand Environment Institute

project it places a strong emphasis on practical and

Bangkok, Thailand

pragmatic ways to address the root causes of

January 2004

priority problems in the coastal zones.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

2

WORLD-W IDE DISTRIBUTION AND EXTENT OF MANGROVE

INTRODUCTION

Global distribution. Mangroves occupy the humid

Loss of Mangrove, world-wide. FAO estimates

tropical belt 30° North and South of the equator,

that a quarter of the world's mangrove has been lost

with extensions beyond these latitudes in certain

over the last twenty years although the rate of loss

areas (Spalding et al., 1997). Two main centres of

during the 1990's (1 percent per annum) is down

diversity have been identified. The eastern area is

from the 1980's rate of 2 percent per annum. This

centred on the Indo-Pacific with its eastern limits in

reflects the fact that many countries have now

the central Pacific, and the western limits, along the

banned the conversion of mangrove for aquaculture,

easter n seaboard of Africa. The western centre

and require environmental impact assessments

includes mangroves found along the African and

prior to large-scale conversion of mangrove lands.

American coasts of the Atlantic Ocean, the

Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, and the Pacific

The total area of mangrove lost in the seven

coastal areas of the Americas. The eastern group

participating countries over different time spans (70

has about five times the species diversity recorded

years for the Philippines) was estimated in 1998 at

in the western region.

4.2 million ha suggesting that over half of the

original mangrove had been lost during the last

Recent estimates (FAO, 2003) suggest that Asia

century. It should be noted that, estimates of both

supports around 39% of the world's total of 14.6

original and present mangrove area vary greatly in

million hectares of mangrove, down from 42% a

the literature, reflecting differences in definition and

decade ago. The bulk of this, 28% of the world's

modes of assessment. The figures in Table 1 are

remaining mangroves, are found in the seven

considered by FAO as the most reliable estimates,

countries participating in this project.

while the estimates for 2000 are considered

indicative only, given the length of time that has

Biological Diversity. Some 41 genera of true

elapsed since the last reliable assessment.

mangrove species are found in the Indo-west Pacific

compared with only 5 genera in the Atlantic and

The causes of mangrove destruction along the

Pacific seaboard of the Americas. The most diverse

coastlines bordering the South China Sea, include

mangrove stands occur in Southeast Asia with up to

conversion to pond aquaculture, particularly of

42 species occurring in a single location. The

shrimp, clear felling of timber for woodchip and pulp

diversity of plant species, is reflected in the diversity

production, land clearance for urban and port

of the animals, both aquatic and terrestrial that are

development and human settlements, and harvest

resident in these communities. In addition to the

of timber products for domestic use. The national

resident plants and animals, mangrove habitats are

impact of each economic activity is difficult to

important staging posts for migratory species

quantify, nonetheless, shrimp culture would seem to

including many shore birds that move seasonally

be the most pervasive economic imperative for

from the northern to the southern hemispheres.

mangrove conversion.

Reversing Environmental Degradation in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand.

Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Viet Nam

In 1996, the countries bordering the South China Sea requested assistance from UNEP and the GEF in

addressing the issues and problems facing them in the sustainable management of their shared marine

environment. From 1996 to 1998 initial country reports were prepared that formed the basis for the

development of a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, which identified the major water related

environmental issues and problems of the South China Sea. Of the wide range of issues identified the

loss and degradation of coastal habitats, including mangrove, coral reefs, seagrass and coastal

wetlands were seen as the most immediate problem. Over-exploitation of fisheries resources and land-

based sources of pollution were also considered significant issues requiring action.

In 1999 the governments, through the Co-ordinating Body for the Seas of East Asia endorsed a

framework Strategic Action Programme that established targets and timeframes for action. In

December 2000, the GEF Council approved this project with UNEP as the sole Implementing Agency

operating through the Environmental Ministries in the seven participating countries and with over forty

specialised Executing Agencies at national level directly engaged in the project activities.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MANGROVES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A 3

Table 1

Estimates of area (Ha) and rates of loss of mangrove habitat in seven countries bordering the South

China Sea, compared with the world totals. [Data from FAO, 2003]

Estimates of mangrove area in Ha

Rates of loss

Most recent Date

1980

1990

2000

1980 - 1990 1990-2000

Cambodia

72,835 1997

83,000

74,600

63,700

-1.1

-1.6

China

36,882 1994

65,900

44,800

23,700

-3.8

-6.2

Indonesia

3,493,110 1988

4,254,000

3,530,700

2,930,000

-1.8

-1.8

Malaysia

587,269 1995

669,000

620,500

572,100

-0.7

-0.8

Philippines

127,610 1990

206,500

123,400

109,700

-5

-1.2

Thailand

244,085 2000

285,500

262,000

244,000

-0.9

-0.7

Viet Nam

252,500 1983

227,000

165,000

104,000

-3.1

-4.5

Total

4,814,291

5,790,900

4,821,000

4,047,200 average -1.8 average -1.7

World

15,763,000 1992

19,809,000 16,361,000 14,653,000

-1.9

-1.1

% world total

30.5

29.2

29.5

27.6

Shrimp farming. A recent centre-page spread in

feed and mature, before moving off-shore in later

the Jakarta Post described the world's largest

phases of their life-cycle.

shrimp farm of 80,000 ha constructed on land re-

claimed from mangrove at Bumi Dipasena.

A different form of transboundary influence is seen

Integrated into the farm was a shrimp feed mill

through the operation of the world markets and

producing 220 tonnes of feed per year and a

global trade in shrimp. The high level of demand for

hatchery producing 8 billion fry/year on a 220 ha

shrimp in Japan, North America and Europe sets

site. Production of shrimp was estimated at 50,000

the world price such that, economic incentives for

tonnes/year and 200 tonnes/day could be stored in

conversion of "non-productive" mangrove habitats

a cold storage facility. Infrastructure included a 160

operate at both the individual and national levels in

megawatt power plant, waste water treatment plant,

producing countries. Hard currency income and

a port, a housing estate for 110,000 people and

economic development fuel the motives at the

2,500 Km of canals.

national level whilst individual producers, at least in

the short-term derive considerable cash income

Unlike such large-scale production the major cause

from cutting their mangrove and converting to

of mangrove loss is conversion to small-scale

shrimp ponds. It is recognised in countries such as

extensive shrimp ponds. Systems that are

Thailand that these short-term benefits result in

unsustainable in the longer term since problems of

longer-term costs that have often to be met from

water quality and disease, result in many extensive

public funds.

low technology, shrimp cultivation ponds being

abandoned after three to four years of operation.

On a smaller scale trade in charcoal derived from

They become unproductive without capital and

mangrove in Cambodia to Thailand was a major

technical investment in maintaining water quality.

cause of mangrove loss in the rec ent past, in the

areas of Cambodia close to the Thai border.

Transboundary issues. From a global perspective

the major transboundary issues surrounding the

Loss of biodiversity. Whilst the inventory of the

loss of mangrove habitats include the loss of unique

flora and fauna associated with mangrove areas in

biological diversity that cannot be replaced, and the

the South China Sea region is far from complete, it

loss of mangrove services. Many off-shore fisheries

is nevertheless obvious that loss of these important

resources such as shrimp and demersal fish breed

habitats has resulted in loss and/or decline in

in mangrove areas and are fished off-shore by more

associated species many of which are now

than one nation's fishing fleet.

considered endangered or threatened. Endangered

species found in mangrove in the region include the

From a regional perspective the loss of off-shore

proboscis monkey, Nasalia larvatus, which eats

fisheries production, both shrimp and demersal fish

young shoots and growing tips of Sonneratia and

may have transboundary implications since the off-

Avicennia trees, the crocodile Crocodilus porosus

shore fishing fleets may not come from the country

and swamp birds including Ardea and Egretta (Low

in which the mangrove habitats occurs. Thus cutting

et al., 1994).

mangroves in one country may impact the fishing

community in a neighbouring country.

Around 30% of the world's remaining mangrove,

occurs in this region but the annual rate of loss is

It has been known for many decades that the off-

55% greater than the world average. Such losses

shore shrimp catch is directly proportional to the

represent a loss of global biological diversity that

area of in-shore mangroves since these provide the

must be a matter of global concern.

habitats within which the juvenile penaeid shrimp

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

4

MANGROVE ECOLOGY AND DIVERSITY

MANGROVE DISTRIBUTION AND DIVERSITY IN THE SOUTH

Animals burrowing in mangrove soils must ventilate

CHINA SEA

their burrows and do so through rythmic movements

of their bodies, producing currents that draw oxygen

Geographic and abiotic limits to mangrove

rich water below the surface. Mangrove trees such

habitats. Mangroves are restricted in their world-

as Avicennia and Sonneratia spp. have

wide distribution by the 240C seawater isotherm

pneumatophores, or breathing roots, that stick up

(Hutchings & Saenger, 1987), thus they form one of

through the surface of the mud, whilst the roots of

the dominant habitats along tropical and sub-tropical

Bruguiera spp. have "knees" above the surface for

coastlines such as those bordering the South China

respiration. These breathing roots have lenticels,

Sea. Mangroves occur on coasts with low wave

which are also found on the bark of Bruguiera and

energy, where land-based sediments carried by

through which oxygen passes into the plant.

rivers, or off-shore marine sediments are deposited

in the inter-tidal and sub-tidal zones.

Unlike coral reefs, mangroves are found in areas

with a wide range of salinities from 0 to 35 psu.

Individual trees may be subjected to varying salinity

regimes depending upon the state of the tide and

the inputs of freshwater from the landward

catchments. Different mangrove species tolerate

different levels of salinity with species such as

Sonneratia ovata preferring the inland more

freshwater environments and S. caseolaris and

Avicennia marina capable of withstanding high

salinity and wave action on the seaward fringe.

Avicennia spp. are also found towards the back of

some mangrove stands where high evapouration

Pneumatophores of Sonneratia sp., Thailand

and low freshwater inputs result in high salinity soils.

In many areas, a distinct zonation in the distribution

Vivipary. Young seedlings of any plant require lots

of plant species can be seen, reflecting the diurnal

of freshwater during their early stages of growth and

patterns of tidal inundation.

the saline environment in which mangroves occur is

not suitable for young seedlings. To overcome this

Ecology of mangroves. Mangrove trees have

problem, species of mangrove trees including those

special adaptations to enable them to live under

in the family Rhizophoraceae are viviparous. The

conditions where the substrate is soft and wave

seeds germinate while still attached to the parent

action threatens to dislodge them. Rhizophora

plant. The long radicle, which enables the propagule

species have stilt roots for support, whilst Avicennia

to penetrate and establish itself in the soft substrate,

and Sonneratia have cable roots.

also serves as a food store once the young plant

becomes separated from its parent.

Prop roots of Rhizophora sp.

Propagules of Rhizophora mucronata

Adaptations to living in a saline environment include

partial exclusion of salt at the root level (as in

Mangrove species and community structure.

Rhizophora) or the presence of salt extruding

The diversity of tree species in the mangroves of the

glands on the leaves (as in Acanthus ). Not only is

South China Sea is the highest in the world. More

salinity high, but oxygen is low in the soils in which

that 30 species of true mangroves are known to

mangroves grow. Just a centimetre or so below the

occur in single locations and some 46 species are

surface of the substrate, the mud is black and

recorded from the region as a whole. Of these

oxygen levels are low. Bacteria that use sulphur to

Brownlowia tersa and Bruguiera hainesii are listed

produce energy thrive in this environment and when

in the IUCN plant red data book, as being

stirred the mud may produce a strong smell of

endangered. Table 2 shows the occurrence of true

hydrogen sulphide.

mangroves in seven countries bordering the South

China Sea.

Reversing Environmental De gradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MANGROVES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

5

Animal diversity is also high, the average number of

Productivity, turnover and carbon storage .

species of macro-crustaceans recorded from 26

Whilst there have been a number of studies on the

sites was 27, with 67 species being found in

abov e-ground biomass and productivity of

Fangchenggang, China. The number of fish species

mangroves, there have been only a few below -

reaches 103 in Can Gio, Vietnam; and the number

ground studies (see Ong et al., 2003).

of resident birds averages 46 species with 98

species occurring in Trad Province, Thailand. These

In terms of sequestering carbon, roots are perhaps

numbers represent minima since the fauna at most

the most important plant component. The annual

locations has not been fully described.

increment of root biomass is 0.42 t C ha-1 in a 20

year-old stand of Rhizophora apiculata, for example

The vertical structure of mangroves in the SCS is

(Ong et al.,1995) which is comparable to the 0.52 t

less complex than that of the lowland terrestrial

C ha-1 annual increment of canopy biomass. Annual

forests in the same area. The number of tree

turnover of small litter (flowers, fruits leaves, twigs,

canopy layers is normally one or two, as compared

and small branches,) accounts for 5.1 t C ha-1.

to the 4 or 5 in terrestrial forests. The height and

diameter of these trees range from over 30 m and

Although, the annual turnover of Rhizophora

100 cm respectively in the case of big Rhizophora

apiculata roots is not available, Ong et al. (1995)

apiculata trees in pristine forests in Indonesia to 2 m

argued that this might be at least in the same order

and 10 cm respectively for small Kandelia candel

as that for leaf turnover. Since this turnover occurs

trees in China. Tree density also varies, ranging

below ground, more of this component will be buried

from around five to six hundred trees per hectare for

than the above-ground small litter (much of which is

mature stands of Bruguiera to around 12,000 trees

exported with the tides or consumed by detritivorous

per hectare of rather stunted trees in

crabs). A significant amount of root organic matter is

Fangchenggang, China. Dominant elements of

leached from roots but the proportion that is

Chinese mangrove forest include the smaller

sequestered in soil is not known.

species such as Avicennia marina and Kandelia

candel.

Table 2

"True" mangrove species recorded from the countries bordering the South China Sea.

Cambodia

China

Indonesia

Malaysia

Philippines

Thailand

Vietnam

Acanthus ebracteatus

X

X

X

X

X

X

Acanthus ilicifolius

X

X

X

X

X

X

Acanthus xiamenensis

X

Acrostichum aureum

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Acrostichum Speciosum

X

X

X

X

X

X

Aegialitis rotundifolia

X

?

Aegiceras corniculatum

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Aegiceras floridum

X

X

?

X

--

X

Avicennia alba

X

X

X

X

X

X

Avicennia eucalyptifolia

X

--

Avicennia marina

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Avicennia marina var rumphiana

X

X

--

Avicennia officinalis

X

X

X

X

X

X

Brownlowia tersa

X

X

X

Bruguiera cylindrical

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Bruguiera gymnorrhiza

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Bruguiera hainesii

?

X

Bruguiera parviflora

X

X

X

X

Bruguiera sexangula

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Bruguiera sexangula Var Rhyncopetala

X

--

Camptostemon philippinense

X

X

--

Ceriops decandra

X

X

?

X

X

X

Ceriops tagal

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Excoecaria agallocha

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Heritiera littoralis

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Kandelia candel

X

X

X

X

X

X

Lumnitzera littorea

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Lumnitzera racemosa

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Nypa fruticans

X

N

X

X

X

X

X

Osbornia octodonta

X

?

X

--

Pemphis acidula

X

X

?

X

Peltophorum pterocarpum

?

X

Phoenix paludosa

X

X

X

X

Rhizophora apiculata

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Rhizophora mucronata

X

X

X

X

X

X

Phizophora stylosa

X

X

?

X

--

X

Scyphiphora hydrophyllacea

X

X

X

X

X

X

Sonneratia alba

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Sonneratia caseolaris

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Sonneratia griffithi

X

X

X1

X

Sonneratia hainanensis

X

--

--

Sonneratia ovata

X

X

XX

X

X

X

Sueda maritime

?

X

Xylocarpus granatum

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Xylocarpus moluccensis

X

X

X

X

X

X

Xylocarpus corniculatum

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

6

FACTORS LIMITING MANGROVES

Limits to mangrove distribution. The seaward

The genera Avicennia and Sonneratia can withstand

extension of mangroves is limited by inundation,

daily inundation and tidal frequencies of between

since no mangrove can survive continual or

700 and 730 per year, but they cannot withstand

repeated inundation of its crown. The landward

permanent inundation of their pneumatophores,

extent appears to be limited indirectly by saline

which must be exposed to the atmosphere for

influences since outside the zones of saline water

several hours a day if the plants are to survive.

penetration the terrestrial halophilic plants are more

successful than mangroves. Species such as

Hypersaline conditions. Occasionally in flatter

Exocoecaria agallocha are quite capable of growing

coastal areas where evaporation rates are high and

and surviving in freshwater environments but their

freshwater inputs low, such as Kampot Province

rare occurrence in such locations in nature suggests

Cambodia, the mangroves are backed by, areas of

that their landward extent is limited by competition.

very high salinity, salt flats. The trees in such areas

tend to have stunted growth due to physiological

Mangrove zonation. Since mangroves occur as a

stress from infertile saline soils, fine sand

fringe of vegetation bordering the boundary between

accumulation and high evaporation rates due to

the land and sea it is not surprising that

wind exposure. The scrubby mangrove growth is

recognizable zones may be distinguished from

backed on the landward side by halophilic salt

seaward to landward side. At the seaward margins

marsh communities.

smaller species such as Avicennia marina, and

Sonneratia alba that can withstand high salinities

and inundation by the tide for long periods,

predominate. In a typical mangrove stand this

seaward fringe is backed by stands of taller

Rhizophera, which in turn give way to Bruguiera, a

genus that is less tolerant of inundation than the

species of the seaward margin.

Similarly along the sides of estuaries, rivers and

creeks draining the mangroves, zones of different

species occur with mangroves giving way to

terrestrial vegetation inland. In Koh Kong Cambodia,

the margins of the estuaries and canals are

dominated by Rhizophora apiculata and R.

mucronata. Further inland are found Avicennia and

Bruguiera followed by Xylocarpus, Ceriops and

Lumnitzera. Nypa fruticans occurs as extensive

stands in the transitional zone between true

mangrove and terrestrial forests. The mangrove

system is often backed by freshwater swamp forest

of Melalueca or peat swamp forest, habitats which

have been largely destroyed on this region.

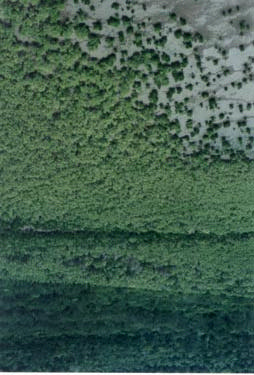

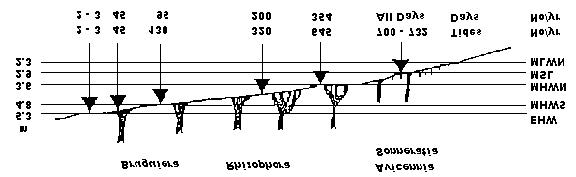

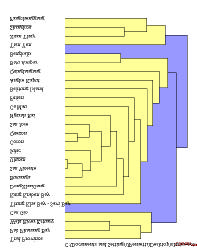

Inundation regimes. Typical inundation regimes

that the dominant mangrove genera of Bruguiera,

Rhizophora, Avicennia and Sonneratia can

withstand are illustrated in Figure 1. Where the

frequency of tidal penetration reaches 200 days and

320 tides per year, Rhizophora is replaced by,

Bruguiera as the dominant genus.

Mangrove zonation at Teluk Bintuni, Papua, Indonesia

Figure 1 Zonation of dominant mangrove genera in relation to annual inundation patterns at Port Klang,

Malaysia. Numbers indicate the number of tides per year and the number of days per year during

which the tide reaches each point in the system.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MANGROVES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

7

DIRECT USE OF MANGROVE RESOURCES

SERVICES PROVIDED BY MANGROVES

Mangrove trees. The direct uses of mangrove

In addition to the direct uses of mangrove trees for

resources are many and varied including

timber, charcoal, thatching, and use of animals such

subsistence use by local communities, and

as fish, crustaceans, and molluscs for food,

commercial, both small and large scale depending

mangroves also provide many important

upon the extent of the system, and the nature of the

environmental services (see Ewel et al., 1998).

resources. The mangrove trees themselves provide

construction timber used for house piles, wharfs and

Coastal protection. In areas of high sediment input

jetties, poles for charcoal making and light

and low wave action the root structure of the

construction. Trees such as Nypa palm provide

mangrove forest traps sediment resulting in upward

fronds used extensively in thatch whilst traditional

accretion of the soil surface, and seaward

communities use the spiny mid-rib to construct thorn

progression of the mangrove fringe. A well-

lined fish traps. Small-scale commercial exploitation

established mangrove forest system not only

of the mangrove trees frequently involves charcoal

provides significant protection to the coastline

production producing fuel for household use whilst

against erosion from the diurnal tidal cycle but also

in contrast, large scale commercial exploitation has

affords some protection against damage from storm

involved clear felling trees for wood chips used to

surges. Because of their shallow root system

produce of rayon.

isolated individual mangrove trees do not withstand

strong winds, and where significant removal of trees

Animal and plant resources. Not only are the

has occurred, the remaining individuals are highly

trees themselves a valuable resource but the

susceptible to wind throw. In a mature mangrove

aquatic animals found in mangrove systems are

stand the inter-locked root systems of neighbouring

used for food and are again exploited at both a

trees provide greater support and hence the habitat

subsistence and a small scale commercial level,

as a whole provides protection to inland areas

often to supply local markets. Frequently the level of

against tropical storm winds.

exploitation reflects not merely the density of people

subsisting directly on the mangroves but also on

Carbon sequestration. Mangroves are also

their proximity to urban centres and the ease with

important as they fix a significant amount of carbon,

which crustaceans, molluscs and fish can be

some 10 tonnes per hectare per year, in the plant

transported to local markets. The mud crab, Scylla

biomass through net primary production. What is

serrata, is a familiar item of cuisine throughout the

more important is the fact that some 1.5 tonnes of

region although pond-culture has now replaced wild

this are sequestered in the mangrove soil for a long

caught animals in many areas. The ponds

period of time (Ong, 1995, 1993). Total root

themselves are often constructed in former

biomass measured in mangroves in Thailand at

mangrove areas contributing to degradation of the

between 138 and 437 tonnes per hectare is

habitat and loss of natural production.

significantly greater than root biomass in temperate

mangroves and tropical rainforest. This particular

Minor uses. A wide variety of minor uses are found

service function may significantly impact the

in different locations throughout the region.

perceived economic value of mangroves in the

Mangrove fruits for example particularly those of

future if trading in carbon credits under the Kyoto

Avicennia, along with sipunculid worms form

Protocol becomes a reality.

distinctive elements of local dishes in southern

China. In Indonesia, Nypa sap is used for alcohol

Biological Diversity Services. In addition to the

production on both a small and large scale, whilst in

intrinsic biological diversity, which mangrove

the Philippines mangrove bark is used as a source

systems support in terms of species restricted to

of Tannin for tanning leather. A widespread but

such ecosystems, mangroves also support both

small scale resource which has potential for larger

migratory and endangered species. Migratory bird

scale production is honey from wild bees, living in

species particularly coastal waders and water fowl

the mangrove habitat.

utilise the mangrove habitats during their seasonal

migrations which may extend from the far North

through the South China Sea to Australia.

Mangroves and associated mud-flats form rich

feeding grounds for such species and breeding

populations of such migratory species may be

dependent upon the continued existence of

mangrove habitats, which are used only for a short

period annually.

Although the number of endangered species, whose

continued existence is dependent upon the

mangrove habitat is small there are nevertheless

several such species in the mangroves bordering

the South China Sea including the estuarine or

saltwater crocodile, the proboscis monkey and two

Molluscs from mangroves and tidal flats on sale in South

species of swamp bird.

Viet Nam

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

8

MANGROVE SERVICES

Nursery areas. MacNae (1974) demonstrated the

Coastal water quality. Mangroves also contribute

relationship between mangrove area and yield of

significantly to maintaining the quality of the nearby

penaeid shrimp from off-shore trawling grounds off

coastal waters. They act as a "sink" not only for

the East coast of Africa. A general relationship is

sediments, but also for nutrients like nitrogen and

apparent between the size of the mangrove nursery

phosphorus, and contaminants such as heavy

area and the resultant fishery, suggesting that

metals (e,g, Tam & Wong, 1995) which are carried

factors regulating the survival of juveniles in the

seawards from sources in the inland areas.

mangroves are important in determining the size of

Quantifying the economic value of such services is

the adolescent and breeding populations

difficult, frequently resulting in an under-valuation of

(Robertson, 1988). The physical complexity of the

the total economic benefits derived from mangrove

habitat provides juvenile shrimps with refuges from

services. In some areas bordering the South China

the high predation rates characteristic of more open

Sea the capacity of natural mangrove systems to

waters. Penaeid shrimp juveniles feed and grow in

absorb additional nutrient inputs from human and

the mangroves before migrating off-shore to

agricultural wastes is being tested, and could

complete their growth.

potentially increase the total economic value of such

systems.

Mud crabs, Scylla serrata undergo a similar life

cycle, the adults undertaking a seaward migration

Without a mangrove fringe to act as a filter

after mating in the mangroves. Berried females can

contaminants and pollutants pass directly to the

be found off-shore at depths of 7 to 70 metres and

coastal waters impacting natural fish production and

the eggs are carried for around 17 days before

aquaculture. The impact of loss of mangroves on

hatching as larvae that use the ocean currents to

pearl production in Guangxi Province China

return to the estuarine environment.

illustrates the importance of this mangrove service

(see box below ).

There is no doubt whatsoever that mangroves are

very important nursery grounds for off-shore

commercial prawn and demersal fish species. The

mangrove national park at Ca Mau in Viet Nam has

been specifically established as a reserve to

enhance and maintain the productivity of off-shore

fisheries.

In addition, since the 1970s, mangroves have been

viewed as providing important sources of food to

coastal fisheries. Recent studies (e.g. Loneragan et

al., 1997 and Chong et al., 2001) using stable

isotopes suggest that this role may in fact be

restricted to areas within the mangrove estuary and

a few kilometers off-shore.

Oyster culture in front of mangroves, Fanchenggang,

China

WATER QUALITY AND PEARL FARMING IN SOUTHERN CHINA

Historically, mangrove thrived along the coastline of Hepu, Guangxi, China, where pearl culture (Pinctada

martensi) has been practiced for nearly 2000 years, mainly in seven areas in the proximity of mangroves,

referred to locally as "pearl pools". By 1995 up to 70% of the mangroves were removed due to coastal

reclamation, and production of good quality pearls declined, suggesting a close link between pearl growth and

mangroves. In Bailong Town of Hepu County, for example, 333 ha of mangroves had been destroyed by 1974.

Before 1974, production was at a level of 1.25 kg of pearls per

10,000 shells, which had dropped to 0.175 kg/10,000 shells by

1999. Over the same period pearl quality declined and the price

also declined to such a low level (5,000 Yuan/kg) that this once

profitable industry was nearly destroyed. Most of the pearl farmers

in Bailong, who had been engaged in pearl production for many

generations, had to choose an alternative job or move to Zhenzhu

Bay in Fangchenggang City of Guangxi to continue their traditional

pearl farming. In 1999, there were still 1030 ha of mangroves in

Zhenzhu Bay where pearl farming is extensively practiced. In 1999

in Zhenzhu Bay , pearl production rate was on average

1.0kg/10,000 shells, and pearl price was 12,000 Yuan/kg. This

suggests that profit from pearl farming in mangrove areas was 13.7

times higher than in areas where no mangrove grows.

Reversing Environmental De gradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MANGROVES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

9

VALUING MANGROVE GOODS AND SERVICES

M ANGROVE DEMONSTRATION SITES

Our current inability to value, in economic terms, the

Goal and Purpose. The primary goal of the

goods and services provided by mangroves stems

demonstration sites is to "test" and "demonstrate"

in part from a lack of agreement concerning the

actions, which either "reverse" environmental

techniques by which value should be determined

degradation or will demonstrate methods of

and in part the lack of comparability between values

reducing degradation trends if adopted and applied

across spatial boundaries.

at a wider scale. In the context of mangrove

ecosystems, environmental degradation results

The total economic value of a natural system

largely from the total or partial conversion of natural

reflects both use and non-use values and whilst it is

habitats to alternative uses, or negative impacts on

possible to value many direct and indirect uses

the biological community structure, productivity or

through market pricing the resulting total value does

species diversity of the habitats, through non-

not reflect the non-use values. Non-use values,

sustainable patterns of resource extraction (over-

such as the value of an endangered species, or the

exploitation). The demonstration sites therefore

aesthetic value of a landscape are difficult to

focus on sustaining biological diversity at the

determine in a manner that allows comparison of

species and habitat levels rather than on the

the results across different social and economic

population or genetic level of biodiversity.

boundaries.

More specifically, demonstration sites are directed

Even the value for direct uses such as the market

to objectives such as: maintaining existing

value of mud crabs collected from mangrove areas

biodiversity; restoring degraded biodiversity;

is highly variable across the region being

attempting to remove or reduce the cause, of

determined by the proximity of the area to markets

degradation; or attempting preventive actions that

and the local economic conditions. Values, where

prevent adoption of unsustainable patterns of use.

they have been determined are therefore highly

specific, relating to a particular area of mangrove at

Maintaining existing biological diversity. Within

a specific point in time.

the region there exist many parks and protected

areas, which with varying degrees of success, are

CONSEQUENCES OF LOSING MANGROVE HABITATS

attempting to maintain the biodiversity that exists

within the park or protected area. Such actions do

When mangrove forests are destroyed and replaced

not address the trend in degradation since they

by alternative land use not only are the species of

effectively establish "refuges" or enclaves of

plants and animals lost but the many services

biodiversity with no, or reduced use. Such

provided by mangrove systems are lost as well.

management regimes can be replicated only by

Since the valuation of such service functions is

extending the total area under this type of

difficult, total economic values of mangroves are

management, and there are severe limitations to

rarely considered in the development decision-

such an expansion, in all countries, which reflect

making process.

land and sea tenure, and current use regimes.

When mangroves are destroyed for shrimp farms

Restoring degraded systems. There are areas in

and other purposes, the decisions are often based

almost all countries of the region where activities

on a consideration of the direct economic returns

involving re-planting and re-forestation, of degraded

from shrimp farming without consideration of the

mangrove are undertaken. Again this type of

total economic value of direct and indirect uses of

potential demonstration activity does not really

mangrove goods and the value of services that are

address the primary objective of the project in that

renewable and sustainable. Mangrove degradation

such actions can only be under-taken once the

causes losses in direct and indirect economic

degradation has occurred.

values that support socio-economic development at

both local and national scales.

Once lost, the productivity of the mangroves that

contributes to wild shrimp and fish production is lost

and whole coastal communities may loose their

means of livelihood. In Viet Nam recognition of the

value of mangrove for coastal protection from storm

surges has led to changes in government policy that

result in the protection and non-use of seaward

mangrove fringes which are seen as protective

barriers for the economic activities taking place

immediately inland.

Replanted mangrove, Trad Province, Thailand.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

10

DEMONSTRATION SITES

Changing patterns of use. There are, few activities

in Thailand are all examples of this type of site.

in the region designed to attempt to reduce the rate

Such sites must have demonstrated successful

of degradation through halting or changing patterns

sustainable use, for a specific purpose, preferably

of unsustainable use, yet it is these forms of action,

over a long period. Demonstration potential is higher

which if successful, and if replicated, will reverse the

for sites where th e techniques used are not

regional trends in environmental degradation. The

widespread throughout the region. It is likely that

value of such demonstration sites appears obvious,

external grant funding requirements for many such

such actions if successful, can be replicated and

sites would be small.

adopted in areas, which are not under conservation

or protection regimes. Sinc e "use" rather than "non-

Process related sites. Again such sites might

use" is the norm for coastal habitats in this region

include existing sites that demonstrate innovative

the potential opportunities for actions of this type are

management processes that are not widespread in

correspondingly greater.

the region. Some examples might include:

community based, local interventions for sustainable

Reducing the causes of degradation. As noted in

use; transboundary sites demonstrating cross-

the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis the major

border collaboration in management of single

cause of mangrove loss and degradation in the

ecosystems; management of habitats by one

region is their conversion to shrimp culture. Where

country with benefits to a second; public private

conversion to extensive shrimps ponds is

partnerships; and, application of new modes of

continuing, actions that result in improved efficiency

organisation and/or management, such as the

of pond culture for longer periods of time, whilst at

current decentralisation of responsibilities to

the same time generating the same level of income,

Provincial and local government in Indonesia).

would reduce the trend of continuing loss of habitat.

Identification of alternative livelihoods that generate

comparable income but have a lower impact on the

state of the habitat, and demonstration of their

utility, transferability, and replicability, would ideally

serve the goal and objectives of the project.

Preventing future degradation. Actions that halt

the adoption of unsustainable patterns of use before

they commence are perhaps, the most difficult

demonstration projects to design, since they involve

not only identifying and demonstrating the

alternatives, but also identifying specific areas

where the threats are most imminent and at the

same time can be potentially altered in advance. For

example one might identify in a national forestry

plan a planned development of large-scale

commercial timber exploitation, which could be

Community managed mangroves, Trad Province, Thailand

implemented using a more sustainable approach. In

the case of commercial timber extraction from

Such sites would be chosen on the basis that they

mangrove systems, rather than clear felling the

have, demonstrated already, or potentially could

entire area, adoption of a rotational pattern of

demonstrate in future, new and innovative modes of

extraction, might result in lower economic returns in

managing the resources and the env ironment. This

the short term, but sustainable economic returns

region is particularly rich in examples of community -

over the longer term.

based and local government management of

coastal areas some of which have proven

What is being demonstrated? The term

successful in the longer term, and some of which

"demonstration site", can be interpreted by different

are less successful. Some successful examples of

individuals, to mean quite different things. In the

community-based management have been

context of this project one needs to examine not

identified as models for use as demonstration sites

only the goals and purpose for the sites, but also:

within the region.

"what" is being demonstrated; to "whom" is it being

demonstrated; and, "how" is it being demonstrated.

Problem related sites. Sites could be chosen to

In considering "what" is to be demonstrated one

demonstrate innovative ways of addressing specific

can identify at least three types of potential

environmental problems such as the management

demonstration site, namely; function related sites;

of sewage pollution via non-water treatment

process related sites; and problem related sites.

methods, using mangrove systems as buffer

habitats. Areas in which over-exploitation is

Function related sites. Existing sites that

occurring could be chosen to demonstrate

demonstrate sustainable use of mangroves for

sustainable extractive use of timber or regulation of

timber production, such as the Matang Mangroves

fishing gear and fishing pressure. This type of

in Malaysia, with over 100 years of sustainable

demonstration site could potentially provide models

forestry use of the area; or demonstrate use for eco-

that would be of wider regional and international

tourism such as Can Gio in Viet Nam; or for

significance.

environmental services such as Pak Phanang Bay

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MANGROVES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A 11

Transboundary management. At present there is

Considerable experience exists in a number of

no area of mangrove habitat under collaborative

countries in the region, including Thailand and

management, involving more than one country, and

Indonesia in the establishment of public awareness

no identified management regime in one country

and extension centres in mangrove areas. Such

that can be shown to provide quantifiable benefits to

centres are designed to enhance public awareness

a second. Identification of such sites and their

of the biology and significance of mangroves and to

adoption as demonstration sites in the framework of

serve as seedling production and training centres

this project provides an innovative demonstration

for mangrove reforestation programmes, operated

site for the region and could serve as a potential

on a community basis.

model for other regions. The mangrove

demonstration proposal in Trad Province, Thailand

is being formulated in collaboration with Cambodian

authorities as one such collaborative management

regime.

In terms of the target audiences and how the

demonstration site is to be operated, the two

questions are clearly related. If one wishes to

transfer a model of successful community based

management from one area to another, or from one

country to another, then the appropriate methods

will differ significantly from those that are applicable

in terms of transferring techniques and experience

at higher organisational levels. Management, at the

level of fisheries extension officers, or management

Mangrove propagules prepared for planting, Trad

at the level of government planners and forestry

Province, Thailand

managers, require quite different mechanisms.

Whilst such centres provide in-country support

Regional Co-ordination. To maximise the potential

through training and public awareness few

benefits of the demonstration site interventions a

mechanisms exist at a regional level for the transfer

regionally co-ordinated framework of structured

of experience between countries. A major role for

visits, study tours an d mechanisms for the transfer

the Regional Working Group on Mangroves lies in

of experiences and good practices must be

providing such mechanisms. Composed of

implemented at the outset. A co-ordinated

government nominated, expert national focal points

programme of exchange visits between

and three regional experts this group represents a

demonstration sites is envisaged that will permit

considerable pool of expertise available in support

individuals from one site to spend extended periods

of the operation and management of the

of on-site training at sites in other countries where

demonstration sites. Each focal point chairs a

appropriate solutions to specific problems are being

national group of institutions with capacity and

applied. Without such a regionally co-ordinated

expertise in all aspects of mangrove research and

programme of training and exchange the lessons

management. This network will serve as the

learned at one site cannot be easily transferred to

mechanism for dissemination , in national

others and the possibilities of self-funded replication

languages , of the experiences and practices

of successful interventions will be reduced.

developed during the execution of the

demonstration site activities.

Table 3

Rank scores for, and primary purpose of, potential mangrove demonstration site proposals.

Total Score Overall rank

Demonstration purpose

Cluster 1

Trad Province

162

1

Community based- management for restoration

Welu River Estuary

133

5

Reversing degradation

Can Gio

120

7

Management for eco-tourism

Pak Phanang Bay

115

9

Management for coastline protection

Cluster 2

Batu Ampar

151

2

Management for multiple uses

Busuanga

135

4

Multiple management through tenurial instruments

Ca Mau

132

6

Management for ecological services

Quinglangang

117

8

Protection of endangered species

Bengkalis

111

10

Management for charcoal production and restoration

Quezon

108

12

Participatory management for aqua-silviculture

Ngurah Rai

108

12

Management for training and public awareness

Angke Kaput

87

14

Management for environmental education

Cluster 3

Fangchenggang

137

3

Cross-sectoral management

Xuan Thuy

109

11

Management for biodiversity conservation

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

12

DETERMINING REGIONAL PRIORITY

DETERMINING REGIONAL PRIORITY OF POTENTIAL

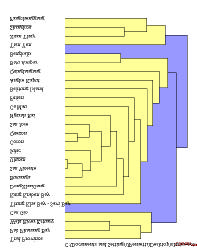

Figure 1 Cluster diagram of twenty-six mangrove sites

DEMONSTRATION SITES

bordering the South China Sea based on

Euclidean distance and mean proximity.

National and Regional Priority. Whilst most

countries have determined national priorities for

intervention including conservation, and sustaining

coastal biodiversity, such priorities have generally

been determined and agreed independently of one

another. The determination of national priority may

not necessarily include consideration of the regional

and or global significance of a particular site or

species. Hence the top priority mangrove site in one

country may fall far below the lower priority sites

from a second country, when both sets are

compared. One major challenge faced by the South

China Sea Project was the determination of the

comparative significance of different national areas

of mangrove habitat that included consideration of

transboundary, regional and global factors.

To initiate the process of determining the

comparative regional importance of national sites it

was agreed by, the Regional Working Group on

Mangroves (UNEP, 2002a; 2002b) that a uniform

set of environmental data would be assembled for

Ranking sites. To arrive at a regional consensus

as many sites as possible bordering the South

regarding the priorities within each cluster the

China Sea. Data were initially assembled for forty-

Regional Working Group initially reviewed the data

four mangrove sites, of which twenty-six data sets

available for all potential sites and developed a set

were judged by, the Regional Working Group, to be

of environmental criteria and indicators reflecting the

sufficiently well documented, to merit inclusion in a

biological diversity, transboundary and regional

regional comparison (UNEP, in press).

significance of each site. A similar system of criteria

and indicators was also developed for the social and

Similarity between sites. Recognising that there

economic characteristics of the sites. Both sets of

exist sub-regional differences in the biological

criteria and indicators were reviewed by, the

diversity contained in mangrove habitats bordering

Regional Scientific and Technical Committee

the South China Sea it was agreed that, a statistical

(UNEP, 2002c; 2003b) prior to being applied to data

comparison of all sites be undertaken in order to

from each site, to derive a score representing a

determine the relative similarity (and difference)

regional view of priority. The system has been

between the sites. These data are presented in

developed in an open and transparent manner

Table 3, where it can be seen that a total of

through the process of consensus such that all

seventeen cells (5.4%) lack entries. This data set

parties understand and accept the final outcome.

represents a compromise between a fully

comprehensive and descriptive set of parameters

Priority sites for intervention. Having agreed the

and what was available for all sites.

criteria, indicators and scoring system and

conducted an independent cluster analysis to group

A cluster analysis was performed using the Clustan

similar sites the rank order within each cluster has

Graphic6 software programme and the resulting

been determined and a set of demonstration

dendrogram is presented in Figure 1. It can be seen

proposals prepared for consideration by the

that the sites fall into three clusters, two of which are

Regional Scientific and Technical Committee and

comparatively small (four sites each). These two

the Project Steering Committee (UNEP, 2003;

small clusters encompass sites in China, Thailand

UNEP, in press).

and Viet Nam representing the northern and north-

western, margins of the South China Sea. The

It can be seen from Table 3 that proposals have not

larger central cluster of 18 sites, is more

yet been developed for all top priority sites within

heterogenous, encompassing both insular and

each cluster, although it is envisaged that this will

mainland sites generally lying in the Southern and

be done at a later date. By focussing on sites for

Eastern portions of the region.

which regional priority is high the project aims to

meet the double objective of conserving globally

The purpose of performing such an analysis was to

significant biological diversity whilst at the same

identify groups of similar sites and ultimately to

time developing, testing, and refining interventions

spread the interventions across different groups

and management actions that can be applied more

thus maximising the between site variation covered

widely throughout the region.

by the selected interventions.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MANGROVES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SE A

13

Table 4

Selected physical and biological data set for mangrove potential demonstration sites bordering the South China Sea.

Zones

True

Density

No.

No.

No

Site

Present

% change

% cover

No

No Fish No Bird

Area

spp

in area mangrove

>1.5m

Crustacean. Bivalve Gastropod Spp

Spp

migratory

assoc

Spp.

high /Ha

Spp.

Spp.

bird Spp.

Trad Province

7,031

5

2

33

1,100

90

32

M

M

55

98

24

Thung Kha Bay - Savi Bay

3,543

4

34

23

1,628

90

58

M

M

36

13

8

Pak Phanang Bay

8,832

3

2

25

1,282

56

36

M

M

85

72

45

Kung Kraben Bay

640

2

0

27

6,100

80

19

M

M

35

75

16

Welu River Estuary

5,478

3

31

33

1,400

60

25

M

M

52

69

15

Tien Yen

2,537

2

-25

13

7,000

60

51

M

M

79

M

M

Xuan Thuy

1,775

3

98

11

9,500

75

61

25

30

90

31

62

Can Gio

8,958

3

100

32

6,000

80

28

17

32

103

96

34

Ca Mau

5,239

3

60

30

7,500

85

12

6

15

36

18

53

Shangkou

812

4

11

9

11,980

90

65

40

33

95

28

76

Quinglangang

1,189

6

-56

25

10,183

80

60

50

62

90

39

32

DongXhaiGang

1,513

5

-14

16

8,433

80

32

24

27

84

43

35

Futien

82

3

-26

7

10,233

80

29

16

21

11

58

99

Fangchenggang

1,415

4

-10

10

12,300

90

67

62

40

71

42

145

Busuanga

1,298

5

-5

24

7,550

90

6

15

36

9

45

27

Coron

1,296

5

-50

26

7,080

M

7

15

37

13

42

34

San Vicente

133

5

-15

14

3,780

80

6

15

36

13

36

40

Ulugan

790

4

-10

16

5,100

85

8

15

36

13

42

39

San Jose

483

4

-80

25

3,180

60

7

13

34

7

48

37

Subic

148

3

-20

23

1,420

90

8

14

35

16

44

57

Quezon

1,939

5

-40

32

4,000

80

5

14

37

11

44

37

Belitung Island

22,457

5

0

8

467

100

5

26

43

71

M

M

Angke Kaput

328

9

-2

12

569

70

29

21

4

22

40

4

Batu Ampar

65,585

5

0

21

2,391

100

11

15

17

51

19

27

Ngurah Rai

1,374

6

27

25

660

100

38

10

32

34

38

42

Bengkalis

42,459

7

-15

18

490

99

12

8

9

3

16

15

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

14

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chong, V.C. Low, C.B. & Ichikawa, T. (2001). Contribution of mangrove detritus to juvenile prawn nutrition: a dual

stable isotope study in a Malaysian mangrove forest. Mar. Biol. 138:77-86.

Hutchings, P. and P. Saengar 1987. Ecology of mangroves. University of Queensland Press. St. Lucia, Australia.

388 pages.

Ewel, K.C., Twilley, R.R. & Ong, J.E. (1998). Different kinds of mangrove forests provide different goods and

services. Global Ecology an Biogeography Letters 7: 83-94.

FAO. 2003. http://www.fao.org/forestry/foris/webview/forestry2

Loneregan, N.R., Bunn, S.E., & Kellaway, D.M. (1997). Are mangroves and seagrasses sources of organic

carbon for penaeid prawns in a tropical Australian estuary? A multiple stable-isotope study. Marine Biology

130:289-300.

MacNae, W., 1974. Mangrove Forests and fisheries. UNDP/FAO, IOFC/DEV/74/34. pp 1-35.

Ong, J.E. (1993). Mangroves - a carbon source and sink. Chemosphere 27:1097-1107.

Ong, J.E. & Gong,W.K. (2002). Vegetated Intertidal : Mangroves & Salt Marshes, in the UNESCO Encyclopaedia

of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), EOLSS Publishers, Oxford, UK. [only in digital format,

http://www.eolss.net].

Ong, J. E., Gong, W. K. & Clough, B. (1995). Structure and productivity of a 20 year-old stand of Rhizophora

apiculata mangrove forest. J . Biogeography 22: 417-424.

Ong, J.E., Gong, W.K. & Wong, C.H. (2003). Allometry and partitioning of the mangrove, Rhizophora apiculata.

Forest Ecology and Management in press.

Talaue-McManus, L. 2000 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis for the South China Sea. EAS/RCU Technical

Report Series No. 14, 108p p. UNEP Bangkok, Thailand.

Tam, N.F.Y., Wong, Y.S. 1995. Mangrove soils as sinks for wastewater-borne pollutants. Hydrobiologia

295: 231-241.

UNEP, 2002a. First Meeting of the Regional Working Group for the Mangrove Sub-Component of the UNEP/GEF

Project "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand".

UNEP/GEF/SCS/RWG-M.1/3. 44 pp In: UNEP, "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South

China Sea and Gulf of Thailand", report of the First Meetings of the Regional Working Groups on Marine

Habitats. 179 pp. UNEP, Bangkok, Thailand.

UNEP, 2002b. Second Meeting of the Regional Working Group for the Mangrove Sub-Component of the

UNEP/GEF Project "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of

Thailand". Report of the meeting, UNEP/GEF/SCS/RWG-M.2/3. 45 pp. In: UNEP, Report of the Second

Meetings of the Regional Working Groups on Mangrove & Wetlands. UNEP, Bangkok, Thailand.

UNEP, 2002c. Second Meeting of the Regional Scientific and Technical Committee for the UNEP/GEF Project

"Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand". Report of the

meeting, UNEP/GEF/SCS/RSTC.1/3. 72 pp. UNEP, Bangkok, Thailand.

UNEP, 2003. Third Meeting of the Regional Working Group for the Mangrove Sub-Component of the UNEP/GEF

Project "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand". Report

of the meeting, UNEP/GEF/SCS/RWG-M.3/3. 50 pp.

UNEP, In press. Fourth Meeting of the Regional Working Group for the Mangrove Sub-Component of the

UNEP/GEF Project "Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of

Thailand". Report of the meeting, UNEP/GEF/SCS/RWG-M.4/3.

Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand

MEMBERS OF THE REGIONAL WORKING GROUP ON MANGROVES

Dr. Sanit Aksornkoae, President, Thailand Environment Institute, 16/151-154 Muangtongthanee, Bond Street

Rd., Bangput, Pakred, Nonthaburi 11120 , Thailand, Tel: (66 2) 503 3333 ext. 401; Fax: (66 2) 504 4826-8,

E-mail: sanit@tei.or.th

Mr. Florendo Barangan, Executive Director, Coastal & Marine Management Office, Department of Environment

and Natural Resources (CMMO/DENR), DENR Compound Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City,

Philippines, Tel: (632) 926 1004, Mobile: (63) 917 873 3558, Fax: (632) 926 1004; 426 3851,

E-mail: cmmo26@yahoo.com

Dr. Hangqing Fan, Professor, Guangxi Mangrove Research Centre, 92 East Changqing Road, Beihai City

536000, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China, Tel: (86 779) 205 5294; 206 5609,

Mobile: (86) 13 367798181, Fax: (86 779) 205 8417; 206 5609, E-mail: fanhq@ppp.nn.gx.cn

Dr. Gong Wooi Khoon, Centre for Marine and Coastal Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Penang,

Malaysia, Tel: (604) 653 2371, Fax: (604) 657 2960; 656 5125, E-mail: wkgong@usm.my;

gongwk@yahoo.com

Dr. Sonjai Havanond, Expert, Marine and Coastal Resources Division, 92 Pollution Control Building,

Phaholyothin 7 (Soi Aree), Phayathai 10400, Thailand, Tel: (66 2) 298 2591; 298 2058,

Mobile: (66) 1 8114917; 661 1731161, Fax: (66 2) 298 2591; 298 2592; 298 2166,

Email: sonjai_h@hotmail.com; sonjai_h@yahoo.com

Dr. John C. Pernetta, Project, UNEP/GEF Project Co-ordinating Unit, United Nations Environment Programme,

9th Floor, Block A, United Nations Building, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand,

Tel: (66 2) 288 1886, Fax: (66 2) 288 1094; 281 2428, E-mail: pernetta@un.org

Dr. Do Din h Sam, Professor, Forest Science Institute of Vietnam, Dong Ngac, Tu Liem, Hanoi, Vietnam,

Tel: (844) 838 9815, Fax: (844) 838 9722, E-mail: ddsam@netnam.vn

Mr. Nyoto Santoso, Lembaga Pengkajian dan Pengembangan Mangrove, (Institute of Mangrove Research &

Development), Multi Piranti Graha It 3 JL. Radin Inten II No. 2, Jakarta 13440, Indonesia,

Tel: (62 21) 861 1710; (62 251) 621 672, Mobile: (62) 81 1110 764, Fax: (62 21) 861 1710;

(62 251) 621 672, E-mail: imred@indo.net.id; puryanti@indo.net.id

Dr. Nguyen Hoang Tri, Director, Center for Environmental Research and Education (CERE), Hanoi University of

Education, 136 Xuan Thuy, Quan Hoa, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Vietnam, Tel: (844) 733 5625; 768 3502,

Mobile: (84) 9 13527629, Fax: (844) 733 5624; 762 7908, E-mail: CERE@hn.vnn.vn

Mr. Ke Vongwattana, Assistant to Minister in charge of Mangrove, Department of Nature Conservation &

Protection, Ministry of Environment, 48 Samdech Preah Sihanouk, Tonle Bassac, Chamkarmon,

Cambodia, Tel: (855 23) 213908, Mobile: (855) 12 855 990; 16 703030, Fax: (855 23) 212540, 215925,

E-mail: vongwattana@camintel.com; kewattana@yahoo.com

UNEP/GEF South China Sea Project Co-ordinating Unit

United Nations Building

Rajadamnoern Nok

Bangkok 10200

Thailand

Department of Nature Conservation and Protection

Ministry of Environment

48 Samdech Preah Sihanouk

Tonle Bassac, Chamkarmon

Cambodia

Guangxi Mangrove Research Centre

92 East Changqing Road

Beihai City 536000

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region

People's Republic of China

Lembaga Pengkajian dan Pengembangan Mangrove

(Institute of Mangrove Research & Development)

Multi Piranti Graha It 3 JL. Radin Inten II No. 2

Jakarta 13440

Indonesia

Coastal & Marine Management Office

Department of Environment and Natural Resources, (CMMO-DENR)

DENR Compound Visayas Avenue

Diliman, Quezon City

Philippines

Marine and Coastal Resources Division

Ministry of Natural Resources & Environment

92 Pollution Control Building

Phaholyothin 7 (Soi Aree)

Phayathai 10400

Thailand

Forest Science Institute of Vietnam

Dong Ngac, Tu Liem

Hanoi

Viet Nam