Physical path

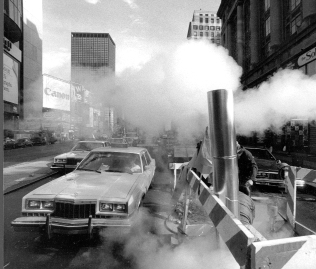

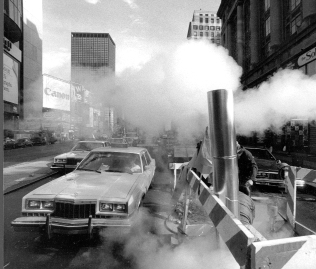

POLFOTO

t

hways of contaminant transpor

IDSTRAND

W

STAFFAN

In the mid-1950 s, airplane pilots flying in the North American Arctic saw a strange, discolored haze

on the horizon. It was thick enough to obscure visibility and different than any flying conditions

they had come across before. In the 1980s, the haze was identified as aerosols of sulfate and soot,

along with some soil particles, which were carried by winds from heavily industrialized areas in

Europe.

This Arctic haze was the first sign that the northern polar environment is closely connected to

activities in other parts of the world. Other observations have added to this insight. Around Sval-

bard, Norway, and in Canada, measurements of toxic organic compounds in polar bears have

shown unexpectedly high levels. Svalbard had been chosen as a background station for environmen-

tal monitoring and was thought to be an example of a clean, undisturbed environment. Where did

the pollution come from? Local sources could not explain the high levels.

A third example made the issue of long-range transport of contaminants into the Arctic even

more acute. A study of traditional foods from the sea showed that some people in native communi-

ties in Canada ingested high levels of the environmental contaminant PCB in their diet. Could the

nourishing food, so essential for health and culture, also be a threat? Again, local sources of PCB

could not explain the high levels. It must have been transported from regions outside the Arctic.

High levels of contaminants in Arctic environments that had been thought pristine led to intensi-

fied research into the pathways by which pollutants reach the Arctic the air and water that enter

the region from industrialized areas of the world. As it turns out, its geographical characteristics

and cold climate make the Arctic a sink for many contaminants that are spread around the globe.

This chapter describes the pathways involved in transferring contaminants from one place to

another and the physical processes that determine their fate in the Arctic.

22

The atmosphere

help break down some contaminants, explains

why sulfates and soot from Eurasia can con-

Physical pathways

The atmosphere contains relatively small

tribute to haze throughout the lower layer of

amounts of contaminants compared with the

the Arctic atmosphere in winter and spring. It

total load in polar soil, sediments, and water.

takes 13 to 16 days for contaminants in the

However, the rapid movement of air makes it

lower atmosphere to travel from Europe to

an important pathway for delivering contami-

Alaska during the winter.

nants to the Arctic. Any chemically stable,

North America and East Asia only rarely

wind-borne material will follow winds and

contribute to Arctic haze since air masses from

weather patterns into and within the Arctic

these areas move over huge ocean distances

region. The atmosphere is the fastest and most

before reaching the Arctic, where low pressure

direct route from the source of pollution:

systems give rain and snow a chance to clean

transport from the sources to the Arctic occurs

the air. They may, however, be important

in a matter of days or weeks.

source areas for occasional bursts of high lev-

els of contaminants that are not efficiently

removed by rain and snow.

Winter and spring winds carry dirty air

In summer, the continental high-pressure

Air-transport patterns are highly dependent on

systems break up, and the low-pressure sys-

season and on the position of major weather

tems over the oceans become weaker. There-

systems. In winter and spring, an intense high-

fore, the transport of air and contaminants

pressure system over Siberia pushes the Arctic

from mid-latitudes becomes much less impor-

front far to the south, so that important pol-

tant in summer than in winter. Summer is also

luted areas of Eurasia are actually within the

warmer, allowing for cloud formation and for

Arctic air mass, the lower one-to-two kilome-

drizzling rain that can remove contaminants

ters of which can move contaminants across

from the air before they are carried far. More-

the pole. Winds that can carry contaminants to

over, sunlight during the summer months al-

the Arctic are therefore more frequent in win-

lows for photochemical degradation of some

ter and spring than in summer and autumn.

contaminants.

The transport of contaminants during the

The position of the

Arctic winter is made even more effective by

Particles take one hop from source to site

Arctic front influences

the lack of clouds and precipitation over the

contaminant transport

areas dominated by high-pressure systems.

Contaminants that are in the form of minute

in the atmosphere. The

Low wind speeds and temperature inversions,

particles, or aerosols, are relatively easy to

figure shows the mean

position of Arctic air

caused by the cold winter weather, allow con-

track. This is also true for gases that transform

mass in January and

taminants to accumulate in the atmosphere.

into particles, such as sulfur dioxide. These

July and the winter and

Rather than falling to the ground in the vicin-

contaminants start their journey with a ride on

summer frequencies of

ity of the source, they follow the large-scale

northflowing winds from the source. Once

winds driving the major

patterns of atmospheric circulation. This,

they land, they usually stay on the ground.

south-to-north transport

routes.

together with the lack of light, which would

They are often labeled one-hop contaminants.

Acids carried as sulfates, non-volatile metals,

and radionuclides are some examples. Non-

Wind frequencies

volatile organic compounds behave the same

Winter: 25%

Summer: 5%

way. One-hop contaminants follow the same

route as Arctic haze, from mid-latitude

sources, mainly in Eurasia, to the Arctic.

The distances over which one-hop contami-

nants travel is determined by the location of

their sources in relation to the Arctic airmass,

er

m

precipitation patterns, and how far the airmass

Arctic front, winter

moves during the atmospheric lifetime of the

front, sum

particles. In the Arctic winter, particles can

tic

rc

stay in the air as long as 20 to 30 days, creat-

A

ing conditions for long-range transport and

accumulation of contaminants in the polar

Wind frequencies

region. In summer, the contaminants usually

Winter: 15%

stay in the air for only 2 to 5 days.

Summer: 5%

Volatile substances

gain global distribution

Some contaminants are transported as gases.

Wind frequencies

Winter: 40%

This is true for volatile and semi-volatile

Summer: 10%

organic compounds. Their behavior is differ-

ent from particle-bound contaminants and

aerosols in that their journey consists of sev-

Modeling the fate of contaminants

A t m o s p h e r e

Where do contaminants come from? How do they get

from one point to the other? Much of what is known

about contaminant transport comes from computer

models that mathematically simulate pathways. The

input to the models are data on emissions, information

Snowpack, river ice,

River ice,

about meteorological conditions such as winds and pre-

Sea ice

lake ice, glacial

shore ice

cipitation, and equations describing processes that

change the chemical and physical characteristics of the

compounds or that remove them from the air.

Single-hop compounds, such as radionuclides and sul-

fate aerosols, can be modeled in the same way as weather

Terrestrial, freshwater

Delta, estuary, fjord

Surface ocean

parameters in computer-based weather forecasts. Winds,

precipitation, temperature, humidity, clouds, and deposi-

Shelf

Central

tion to Earth's surface are the major factors that deter-

mine the pathway from source to deposition site. Such

models have been used to describe the fallout from

Chernobyl, the fate of pollution from the Kuwaiti oil

Sediments

Sediments

Sediments

fires, and the impact of acid rain in Europe, eastern

North America, and southeast Asia.

Models for multi-hop compounds are much more

complex. In addition to the meteorology, a model has to

describe how the contaminant moves between different

environmental compartments, such as the atmosphere,

Deep

the land, and the ocean. To get a more accurate picture,

ocean

the compartments are often subdivided: Will the contam-

inant enter the surface of the ocean and remain there or

will it also reach the deep layers? Will it adhere to parti-

cles and end up in soil or sediments, or will it dissolve in

water and follow land runoff to a river? Often, the same

contaminant will be present in several compartments, and

there is an exchange between them that depends on the

A multi-compartment representation of the major pathways

Bottom

temperature and on the total mass of the compound pre-

water

of contaminants to and within the Arctic environment.

sent in each compartment. The model should, for exam-

ple, be able to describe how a decrease in the load of

contaminants in the atmosphere can turn a sink, such as

the oceans, into a source. Similar models exist for marine

Sediments

environments. An illustrative example of this phenome-

non is how the pesticide hexachlorocyclohexane spreads

around the globe by moving in and out of the ocean.

eral hops. The compounds are first picked up

air, which eventually land on the ground. They

by the winds as gases. They can then land on

can also condense directly onto the Earth's sur-

the ground, on ice, or in the oceans by adher-

face. At the low temperatures typical of the

ing to particles or organic films, as well as by

Arctic, they are not as likely to revolatilize as

dissolving in water. But this is not necessarily

in warmer climates. Another explanation is

the end of their journey. When summer brings

that gases dissolve in water more readily at

higher temperatures, the compounds can vol-

low Arctic temperatures than in warmer envi-

atilize again, re-enter the atmosphere, and con-

ronments.

tinue their journey as gases. If the contami-

nants do not break down, as is the case for

The breathing oceans

persistent organic pollutants and mercury, and

if the temperature conditions are right, the

For multi-hop contaminants, it is difficult to

process can repeat itself a number of times.

pinpoint the sources of the high levels that

Eventually, the compounds might break down

have been detected in the Arctic. Some of these

to less harmful chemicals or be deposited in

contaminants have been used for decades, dur-

bottom sediment in oceans and lakes.

ing which time a portion of the chemicals has

Multi-hop compounds can travel great dis-

ended up in the world's oceans or in soils. For

tances and become truly global in distribution.

some compounds, the concentration in the

At some point in their journey, the winds are

oceans can be thousands of times higher than

likely to carry them into the Arctic, which

in the air. This capacity to hold on to contami-

explains why chemicals that have never been

nants is especially pronounced when the water

used in the Arctic can still be found in the tis-

is cold, as it is in the Arctic Ocean. When the

sues of people and wildlife in the region.

temperature increases, the capacity of the

For some compounds, the levels are higher

water to retain the contaminants decreases,

in the Arctic than one would expect, even tak-

and the oceans `breathe out'. Because the mass

ing transport into account. Why? One expla-

of contaminants is higher in the water than in

nation lies in the cold climate. As the tempera-

the air, the ocean can be expected to have `bad

ture drops, the compounds condense out of the

breath' for a long time, at least ten years for

gas phase onto particles or snowflakes in the

the Arctic Ocean. For contaminants that

adhere to particles, soil can serve as a similar

condense on the cold ground where they

24

reservoir.

adhere to soil particles or plants. For many

Physical pathways

To understand the levels of multi-hop conta-

contaminants in the Arctic, wet and dry depo-

minants in the air, one has to know the condi-

sition from the atmosphere is the major pollu-

tions under which the oceans and the land

tion source.

breathe out. First, there is a seasonal pattern.

For example, an increase in water temperature

may lead to a release of contaminants. The

The land and rivers

breakup of ice in spring and the fall break-

down of water stratification can also turn the

The Arctic landmass receives contaminants

ocean into an important seasonal source to the

from the atmosphere. Contaminants are also

air. Contaminants captured in snow or soil

transported to the Arctic by large rivers that

behave in a similar manner and can also be

can move material from polluted areas farther

released to the atmosphere when temperatures

south along the river. Mines, metal processing

rise in summer.

facilities, factories, oil and gas drilling, waste

Over the long term, the concentration of

dumps, and settlements can add to the local

contaminants in the air will determine the role

load. The diagram opposite gives a conceptual

of oceans and soils as sources. If air concentra-

picture of some different pathways.

tions drop, as they would if we were to place

The fate of contaminants in the terrestrial

restrictions on use, the oceans and the land

environment depends on the landscape as well

may release more of their loads.

as on the physical and chemical characteristics

of each compound. Water-soluble compounds

will be carried by snow-melt, surface water,

Rain, snow, fog, and rime clean the air

groundwater, and rivers. Unless they degrade,

Contaminants are cleaned out from the air by

they tend eventually to end up in the ocean.

several processes. They can be caught when

Contaminants with low water solubility nor-

raindrops or snow crystals form in a cloud or

mally adsorb onto particles in the soil or sedi-

when the rain or snow is actually falling. Fog

ment. Their fates depend on whether erosion

can scavenge contaminants and deposit them

will wash the soil into waterways and, if so, on

when it condenses onto surfaces. Rime ice,

what happens to the particles during a river's

journey to the ocean.

137

Radioactive rain

Cesium deposition, kBq

Precipitation, mm,

May-June 1986

28-30 April,

Precipitation was important

1986

in washing wind-borne ra-

Snowmelt creates a chemical surge

dionuclides from the Cher-

Melting snow plays an important role in trans-

nobyl accident out of the air

2

and onto the ground.

porting contaminants in the terrestrial envi-

In Scandinavia, the de-

ronment. By spring, the snow has had a whole

position of radionuclides

2

winter to accumulate contaminants from the

15

was very similar to the pat-

0

30

air. A deep snow pack can even retain volatile

tern of local rain showers.

9

5

5

2

9

5

contaminants, which shallow snow packs

The areas that had rain the

15

10

20

days after the accident were

20

would release back to the air.

30

those with the highest levels

50

When the temperature rises, water-soluble

0

of cesium-137 in the ground.

30

chemicals concentrate in the melt-water, and

25

For example, the city of

30

25

85

the initial 20 to 30 percent of the meltwater

Gävle

20

Gävle, where it rained the

2

15

can remove 40 to 80 percent of the total mass

day after the accident, re-

95

0

ceived substantial deposi-

of pre-melt contaminants. Most of the meltwa-

5

tion, as did the reindeer

ter flows over frozen ground directly into

herding grounds in the mid-

streams and lakes. The chapter on acidification

9

dle parts of northern

9

provides an example of the effect this chemical

Sweden. The Saami reindeer

9

surge can have on the water quality of small

herders farther north were

0

much less affected by the

5

streams.

fall-out.

5

Meltwater can also be a powerful erosive

5

force. In areas where the ground cover has

been disturbed, the rushing water easily forms

which forms when supercooled cloud droplets

erosion gullies and washes away soil. Over-

freeze on contact with snow crystals or sur-

grazing, seen in Scandinavia, Russia, and

faces, is also an important scavenger of conta-

North America, can thus affect water quality.

minants from the air. In Greenland, rime ice

Construction work is another potentially dam-

has been estimated to contribute about 5 per-

aging activity, especially if the permafrost is

cent of the annual snow load, while account-

disturbed.

ing for approximately 30 percent of the annual

Erosion also introduces suspended particles,

deposition of contaminants.

which provide surfaces to which contaminants

An additional route from the air is dry

can attach. Therefore, erosion can increase

deposition. Particles can land by themselves

contaminant transport in a river.

and semi-volatile, gaseous contaminants can

Revolatilization

25

W e t a n d d r y a t m o s p h e r i c d e p o s i t i o n

Revolatilization

Physical pathways

Revolatilization

Wetland

(bog /swamp)

Coastal

runoff

Transformation

Lake

Watershed

Ocean

Transformation

Resuspension

Groundwater

drainage Runoff

Wetland outflow

Sedimentation

Water +

particulate matter

Sedimentation +

transformation in

transport

Resuspension

delta/estuarine zone

Industrial

Municipal

Sedimentation

Riverine transport

Mining

Transformation

Different pathways of

contaminant transport

in the terrestrial and

Agriculture

freshwater environ-

ments.

water from the ground, most of it in late sum-

mer. Only during this short period can the

chemical and biological composition of the

active layer affect the contaminant load

Permafrost makes surface water

brought by precipitation. In spring and early

vulnerable

summer, the lake gets its water directly from

Even when the ground is not completely

surface runoff, and the active layer plays no

frozen, the shallow active layer of Arctic soils

role. Farther south, groundwater becomes pro-

makes patterns of water transport over and

gressively more important as the active layer

through the ground very different than in

becomes thicker.

warmer areas. Specifically, there is a greater

risk of surface water contamination, whereas

Rivers are key pathways

the groundwater is relatively more protected.

For example, a small lake in a permafrost area

Rivers are central to many Arctic settlements,

might only receive slightly more than half its

providing drinking water and fish for food.

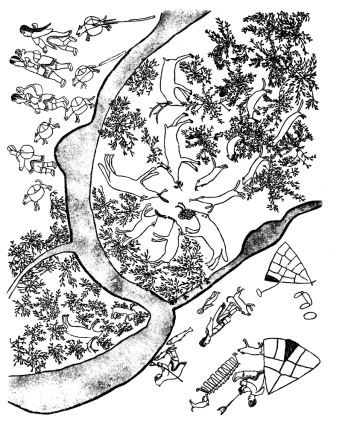

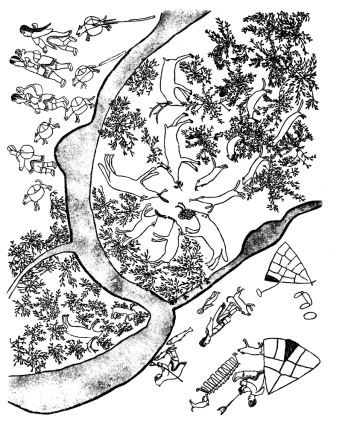

Tundra with River.

Drawing: Ruth Qual-

luaryuk.

They are also important pathways for conta-

of the Kola Peninsula was treated according to

26

minants.

specified purification standards. In general,

Physical pathways

Rivers are also key pathways for long-range

however, the main watersheds in both Russia

transport. They can gather water and particu-

and North America are relatively clean, and

late matter from huge catchment areas and

they have many lakes and reservoirs that act as

transport them over long distances. The major

traps for contaminated sediment.

inflow of freshwater to the Arctic Ocean comes

from rivers that originate outside the Arctic.

Early summer brings peak input

The catchment areas of large rivers often

and floods

include many diffuse sources of contaminants,

such as agricultural runoff loaded with pesti-

The flow in Arctic rivers is highly seasonal,

cides. Discharges of municipal and industrial

especially in those unregulated by dams and

sewage from heavily populated and industrial-

reservoirs; see the graphs opposite. In winter,

ized areas south of the Arctic also contribute

water flow is very low, and some rivers even

to the contaminant load. Other polluting activ-

freeze to the bottom. Peak flow usually comes

ities are mining and oil and gas exploitation.

in June and July, and this is when one would

In Russia, some rivers are used as roads and

expect the largest input of contaminants to

for dumping dirty snow in winter. Contami-

the Arctic Ocean.

nants from vehicles and from materials gath-

The peak flow in the rivers coincides with

ered in the snow will also be carried by the

the greatest transport of river ice, and in some

water or by the ice during spring melt.

rivers the combination of high flow and ice

Some of the Arctic rivers have polluting

jams leads to flooding. If the landscape is flat,

activities in their catchment areas. The major

as is the case in many parts of the Russian tun-

Russian rivers, in particular the Yenisey and

dra, the water can cover vast areas. Floods can

the Ob, have their upstream basins in heavily

leave contaminant-laden sediments on the

developed areas with industries, urban centers,

flood plain, temporarily removing them from

and intensive agriculture. However, very little

the riverine pathway. However, in years where

is known about what these rivers actually

flooding is extreme, the water may pick up

transport. In North America, the Nelson River

previously deposited material, and the load of

system, which empties into Hudson Bay, flows

contaminants will then reflect inputs from sev-

through areas with intensive agriculture in

eral years.

mid-west Canada. The same is true, though to

Slower-flowing rivers with well-developed

a lesser extent, for the Mackenzie River.

flood plains usually do not rise until the rivers

The large rivers in the Arctic and in the sub-

are clear of ice and might thus be more effici-

arctic receive most of their water during spring

ent in moving contaminants to the coast.

snowmelt, and in most areas the melted snow

In summer, heavy rains or periods of dry

is also the most important source of contami-

weather control river flow. In small waterways,

nation. In highly urbanized regions, such as

the water level can change dramatically depend-

the large industrial cities of the Russian Arctic,

ing on the weather. Nonetheless, most sedi-

direct discharges of wastewater are equally

ment transport occurs during the spring flood.

important.

In Russia, large volumes of industrial and

River ice gathers contaminants

municipal waste water are not treated. For

example, in 1994 less than 5 percent of the

River ice has a special role in the transport of

Dirty river ice,

Lena delta.

waste water produced in the Murmansk region

contaminants. The ice gathers material from

the atmosphere and from the river itself as the

water freezes. The incorporation of particle-

borne contaminants from the water can con-

tinue throughout the winter as the ice grows.

When the water freezes all the way to the

bottom of a river, material from the river bot-

tom gets caught in the ice. Also, if the entire

water column in the river is supercooled, i.e.

has a water temperature below freezing, a sud-

den change in temperature or turbulence can

lead to ice formation around rocks and sedi-

ment on the bottom of the river. Known as

anchor ice, these formations can lift rocks as

heavy as 30 kilograms. Supercooled water is

also involved in formation of frazil ice, which

collects small particles in the water and incor-

porates them into the ice cover. As a result, river

ice can contain large amounts of sediments.

The sediments and any contaminants in the

HEIDI KASSENS

ice itself are released to the river water during

the spring melt, when the biological producti-

Water discharge, m3/second

27

vity of the water is at its peak. The seasonal

40 000

Mackenzie River, 1973-1990

freeze-thaw cycle thus creates conditions in

Daily mean discharge

35 000

Average of daily means

which the contaminant load built up in winter

can be effectively incorporated into animals.

30 000

25 000

Lakes and dams trap sediment

20 000

The landscape through which a river flows

15 000

plays an active role in the fate of contami-

10 000

nants. Many contaminants are bound to par-

5000

ticles, and sedimentation and resuspension

processes will determine whether the contami-

0

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

June

July

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

nants reach the Arctic Ocean or are deposited

along the way. When a river flows slowly, par-

Concentration of sediment in water, mg /liter

4000

ticles usually settle, and bottom sediments can

Mackenzie River, 1972-1991

Daily mean concentration

become enriched in metals, persistent organic

3500

Average of daily means

pollutants, and hydrocarbons. However, the

river bottom is usually only a temporary trap

3000

since turbulent flow can lead to the resuspen-

sion of particles. Large lakes, on the other

2500

hand, can serve as permanent traps for conta-

minants. Great Slave Lake on the Mackenzie

2000

River system, for example, blocks much pole-

ward transport of contaminants, particularly

1500

those bound to particles.

1000

Man-made lakes are no less important.

Dams constructed along the Yenisey River in

500

the 1960s and 1970s illustrate the role of man-

made lakes as particle traps. Eight reservoirs,

0

controlling about one-fourth of the river flow,

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

June

July

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

caused a three-fold reduction in the amount of

tances even when contaminants are adsorbed

Top: Variation in dis-

sediment that reached the mouth of the river.

to particles. Through resuspension of bottom

charge of water in the

These sediments were deposited in the reser-

sediments, these fine clay particles also gather

Mackenzie River over

the year.

voirs. Dams can also change the seasonal pat-

metals and hydrocarbons originating from

Bottom: Variation in

tern of the flow, distributing it more evenly

natural weathering processes.

concentration of sedi-

throughout the year.

Living organisms help the sedimentation

ment in the water of the

The fate of specific contaminants is deter-

process in lakes, just as they do in deltas and

Mackenzie River over

mined by how well they adhere to particles

estuaries. Phytoplankton extract material that

the year.

and by the type of particles in the water. The

is dissolved in the water, and many zooplank-

smallest particles often have the highest con-

ton and larger filter feeders gather suspended

centrations of contaminants due to their

matter, effectively packaging small particles

larger relative surface area, and these settle

into larger ones. The material is deposited on

less quickly than coarser material. There is

the bottom, which becomes a mixture of inor-

thus a potential for transport over long dis-

ganic sediment, shells, and excrement.

Flooding of Yenisey

River shown in yellow

NOAA/TSS/AKVAPLAN-NIVA

©

on satellite image.

Rivers carry fresh water and

time in the flat landscape. During spring melt,

sediment to the Arctic seas

they will follow the runoff and end up in rivers.

In total, Arctic rivers carry

Wetlands are thus important secondary sources

about 4200 cubic kilometers

Yukon

60 million tonnes

of pollution to surface rivers in this region and

of water per year into Arctic

Kolyma

are likely to remain so for a long time.

seas, along with about 221

Mackenzie

16.1 million tonnes

million tonnes of sediment

Another example where wetlands act as sec-

42 million tonnes

per year. The landscape de-

Lena

ondary sources is in areas with intensive metal

termines the role of each

17.6 million tonnes

industries, such as the Kola Peninsula, where

particular river. Those cros-

Nelson

Yenisey

metals are likely to leach into waterways even

sing flat, frozen tundra gen-

5.9 million tonnes

0.7 million tonnes

after emissions decrease.

erally carry relatively small

16.5 million tonnes

Ob

amounts of sediment. The

Mackenzie River, on the

13.5 million tonnes

other hand, flows through

Pechora

3.8 million tonnes

a much steeper landscape,

Where the river

Northern Dvina

with less permafrost and

meets the sea

with abundant surficial

Yearly discharge of

material that can be eroded.

suspended sediment

Rivers enter the ocean through estuaries and

by major rivers.

Consequently, it carries

deltas along the coastal zone. The physical and

larger amounts of sediment.

biological processes in these environments

have a major impact on the fate of contami-

Lakes do not control the transport of water-

nants carried by river water and river ice.

borne contaminants as much as they do for

particle-bound substances. Often, snowmelt

Deltas and estuaries serve as particle traps

flows through small Arctic lakes without mix-

ing. Therefore, at least for headwater lakes,

In the context of contaminant transport, the

most of what comes in also flows out. The

major physical role of deltas and estuaries is as

load of contaminants in lakewater is therefore

particle traps for particulate matter in river

more likely to reflect input from rain and

water. Rivers flow more slowly and with less

ground runoff during summer.

turbulence when they reach the coast, allowing

particles to settle. The containment of particles

is enhanced when sediments that settle farther

Wetlands can be contaminant sources

out are transported back toward the river

Through snow, rain, and dry deposition, the

mouth by inflowing seawater. The sediment is

vast wetland areas in the Arctic, with numer-

thus advected back upstream before it finally

ous shallow lakes, swamps, marshes, and bogs,

deposits. The settling process is enhanced by

gather contaminants from the air. Water in

the mixing of fresh water and sea water, which

wetlands naturally contains much organic

makes fine colloidal particles stick together

matter, such as humic substances from peat.

and become large enough to settle.

Hydrophobic contaminants tend to bind to

Some water-soluble substances can also be

organic matter, in both soil and water. Some

caught in deltas and estuaries. The main mech-

of these bound contaminants remain in the

anism for this is flocculation, in which dissolv-

ground but some will enter waterways.

ed organic and mineral substances are gath-

Local sources add to the load. For example,

ered into suspended particles. The process is

oil and gas exploitation in northwest Siberia

driven by changes in acidity and salt concen-

releases untreated waste water as well as oil to

tration. Living organisms also help the sedi-

depressions in the landscape. The cold weather

mentation process.

does not allow for much decay of the organic

The efficiency of coastal sediment traps

Mackenzie River delta.

pollutants, which are likely to stay for a long

depends to a large extent on whether a delta is

formed, i.e. a depositional plain where the

sediments build up new land into the sea; or if

tides and waves eventually carry most sedi-

ments away from the river mouth. The largest

deltas are created by major rivers draining

large areas and carrying abundant sediment. If

the continental shelf is shallow, the delta plain

can continue far out to sea, beneath the ocean

surface. Two examples of huge deltas are those

of the Lena River in Russia and the Mackenzie

River in Canada. The Mackenzie Delta accu-

mulates several centimeters of overbank sedi-

ment every year. This can be compared with

accumulation rates of 10-100 centimeters in

1000 years in estuaries, or 1-3 millimeters per

WIDSTRAND

1000 years for ocean sedimentation.

Large amounts of the suspended matter in

STAFFAN

rivers can thus be deposited and excluded from

further transport to the open ocean. Along the

during part of the year, which allows for the

29

Russian Arctic coast, only 10 to 20 percent of

exchange of contaminants between water and

Physical pathways

the particulate matter in the Ob and Yenisey

air; and they have high biological productivity,

Rivers travels farther than the borders of the

which provides a route for contaminants into

deltas and the Kara Sea shelf.

the food web. The diagrams below summarize

the major processes for redistribution of conta-

minants in the coastal zone.

Landfast ice

keeps sediments close to shore

Sea ice may gather

Many Arctic rivers discharge into areas with

and transport contaminants

extensive ice cover. Maximum river flow

occurs at the time that the landfast ice in the

In recent years, sea ice has become a focus of

shelf seas is about to break up. If the early,

research concerning contaminant pathways in

sediment-laden river water flows on top of the

the Arctic. The picture is just emerging, but

ice, the heavy load of dark particles will speed

some hypotheses are interesting to consider.

up the melt, and the sediments will settle to the

There are two major ways in which sea ice

bottom along the coast. If the near-shore ice

gathers contaminants: from the atmosphere,

cover is anchored to shallow off-shore banks,

where its large surface area makes it an effi-

it can form a barrier to offshore transport of

cient trap for air-transported contaminants,

any floating material such as dirty river ice. In

and from the water during ice formation. Sea

both cases, the sedimentary material will most

ice can incorporate sediments in much the

likely be deposited near the shore.

same way as river ice: frazil and anchor ice

formation capture material from the sea bot-

tom. This incorporation of particles in ice is

The continental shelves

especially effective for silt-size or smaller parti-

cles. Because many contaminants are preferen-

The shallow continental shelves surrounding

tially associated with these fine-grained parti-

the Arctic Ocean are important for the trans-

cles, the ice can become more contaminated

port of contaminants within the Arctic for

with these substances than the water.

three reasons: they are the primary areas of ice

When ice formed in the shelf seas becomes

formation and ice melt; they have open water

part of the pack ice, associated contaminants

Atmospheric transport

Gas exchange

Sediment deposition

Turbid plume

River inflow

Pack ice

Ice melt

Summer stratified layer

Flocculation

Bottom

resuspension

Biogenic

Particles from

by waves

particles

melting ice

Salt wedge

Upwelling

Spring/summer

Gas exchange

Sediment incorporated in ice

River inflow

Landfast ice

Shear

zone

Strong stratification

Anchor ice

Brine drainage

Suspension

freezing

Polar mixed layer

Ice scouring

Summary of different

processes determining

the fate of contaminants

along the coast and in

Winter

the shelf seas in spring/

summer and in winter.

contaminant-laden particles often form pools

of dirt on the surface, so called cryoconites.

Once at the surface, any semi-volatile material

can interact with the atmosphere. Other mate-

rials will be released when the ice melts.

Sediment traps along the Fram Strait show

that most of the ice-carried debris will be

released in the marginal ice zone. The timing

and location of the ice melt coincide with the

bloom of biological activity, and thus provides

an opportunity for contaminants to enter the

food chain. Many small plants and animals

live at the ice-water interface (the epontic

zone), and can be exposed to much higher lev-

els of contaminants than would be expected

from the contaminant load of the water.

Similar processes also occur under the ice in

the central Arctic Ocean, but are less well

understood.

If the sediments have aggregated into pel-

lets, they will sink to the ocean floor much

faster than fine particles. If the ocean is deep

enough, contaminants in these pellets are less

likely to be taken up in the food chain.

Water-soluble contaminants

follow the brine

NOAA/TSS/AKVAPLAN-NIVA

©

Water-soluble substances behave differently

Satellite image of sea ice

are carried away by the drifting ice. Much of

than those that adhere to sediments, but sea-

in the Barents and Kara

the ice in the Arctic Ocean circulates for one to

ice formation can still provide a route for long

Seas. The large white

seven years before it leaves the basin and

range-transport. The mechanism is quite dif-

area is snow-cover on

melts. The map on page 32 shows the major

ferent. When sea water freezes, brine (a con-

Novaya Zemlya, Russia.

circulation patterns.

centrated salt solution) is expelled into the

Ice is not a passive vessel for contaminants.

water, and water-soluble compounds follow

Melting at the surface, drainage, and refreez-

along. If the water is not stratified, the brine

ing from the bottom will redistribute the mate-

mixes with the surrounding water and can

rial carried by the ice. Most of it will appear at

penetrate into the deep parts of the ocean. In

the surface after a few years. The dispersed,

the absence of particles, even contaminants

Ice can scour the sea floor

Icebergs are a spectacular feature of Arctic ice. They are pieces of glaciers that have broken off and floated away in the sea. Calving glaciers

cover much of Greenland, Svalbard, Franz Josef Land, Severnaya Zemlya, and the northern island of Novaya Zemlya. The photos show ice-

bergs near the Jakobshavn Icebrae, Ilulissat.

Beneath the surface, icebergs can reach depths of more than 100 meters, and can scour the bottom in shallow areas. Such scouring marks

can be several meters deep and tens of meters wide. Icebergs are not important for transporting contaminants but might disrupt waste contain-

ers that have been dumped on the sea floor.

Sea ice can also disturb the bottom, especially along shallow shores and when it is compressed into thick pressure ridges. The ridges can

scour the bottom and stir up contaminant-laden sediment, making it available to biota and to further transport by water currents.

Iceberg sources

Arctic Ocean

Major

Minor

Canada

NILSSON

Ilulissat

Common iceberg tracks

Greenland

PETERSEN; right: ANNIKA

Atlantic Ocean

Common iceberg tracks

Left: HENNING SLOTH

that normally adhere to particles, such as

radiocesium, follow the brine.

31

Open water allows

for atmospheric exchange

Pacific water

In summer, the shelf seas are relatively free of

ice, while in winter, ice covers the areas closest

to the coast. Farther out, between the landfast

Beaufort Gyre

0.8

Transpolar Drift

ice and the permanent pack ice, offshore winds

often form areas of open water. These flaw

leads, also called coastal polynyas, can extend

Precipitation

0.05

over thousands of square kilometers.

Flaw leads along the coast are important

areas for the interchange of semi-volatile cont-

1.9

aminants between water and air. For example,

0.04

1.7

2.0

soluble, gaseous pollutants that make their

way to the Arctic can dissolve in the cold Arc-

tic waters.

1.2

0.16

Moreover, the leads typically form the locus

3.1

4.9

of ice break-up from late April to mid May

Atlantic water

and thus are a gathering place for many marine

animals. As is the case along the marginal ice

8.0

zone, the high primary productivity and rich

Atlantic water + Intermediate layer, 200-1700 m

wildlife of these areas provide a route for cont-

Pacific water, 50-200 m

aminants to enter biological pathways, as is

Surface water circulation

further discussed in the chapter Arctic Ecology.

River inflow

Figures are estimated in- or outflows in Sverdrups

The transport of water

(million m3 per second)

with the main ocean cur-

The Arctic Ocean

other oceans only through restricted passages.

rent systems in the Arctic.

The major inflow of ocean water passes from

The Atlantic-layer water

mass originates from the

The Arctic Ocean and the surrounding seas

the North Atlantic through Fram Strait and

surface of the North At-

receive contaminants from air, other oceans,

the Barents Sea. There is also some inflow

lantic Ocean and descends

rivers, and from direct discharges. The fate of

from the North Pacific through the Bering

below less-dense Arctic

these substances is determined both by Arctic

Strait. The ocean transport of pollutants is

Ocean surface water,

which is affected by fresh-

Ocean circulation patterns and by the stratifi-

slow, taking years to decades to transport

water from rivers. The

cation of the ocean waters.

water from industrialized, temperate coastal

Pacific water mass is pro-

Geographically, the Arctic Ocean is often

regions to the Arctic Ocean.

duced by modification of

described as a `mediterranean' sea because it is

The movement of water and pollutants in

water entering the Bering

surrounded by land, communicating with

the Arctic Basin is best understood by viewing

Strait on the broad Chuk-

chi Shelf and occurs in the

Canada Basin.

Ice

Polar mixed layer

Pacific halocline

Atlantic halocline

Bering Strait

Fram Strait

Depth, m

0

ca. 10 years

200

Pacific water

ca. 10 years

400

Atlantic water

ca. 25 years

600

ca. 30 years

Atlantic layer

800

1000

Arctic deep water

Norwegian Sea

Bering

Strait

and Greenland Sea

ca. 75 years

deep water

2000

Canada

Makorov

Basin

Basin

Fram

Alpha

Strait

Ridge

3000

ca. 300 years

Amundsen

Nansen

Basin

Basin

Vertical section of the

Arctic Ocean and the

ca. 290 years

Nansen

Lomo-

different water masses

Gakkel

nosov

with their approximate

Ridge

Ridge

4000

residence times. The ver-

tical scale is exaggerated

Bold figures denote residence times

compared to the hori-

zontal scale.

32

breaks up and allows surface waters to sink

and deep water to rise to the surface. This hap-

pens every fall and winter when the water cools

and when ice starts to build, expelling brine.

This vertical mixing allows both nutrients and

contaminants from deeper layers to reach the

surface in the shelf seas and Nordic Seas.

5

4

Two main features characterize the circula-

tion of the surface water: the Beaufort Gyre

3

6

Beaufort

and the Transpolar Drift; see map left. The

Gyre

2

Beaufort Gyre is a large clockwise gyre extend-

ing over the entire Canadian Basin. It circu-

lates slowly between the pole and the Cana-

1

dian Archipelago. In this way, water is ex-

Transpolar

Drift

ported both to Baffin Bay through the Cana-

dian Archipelago and to the Transpolar Drift.

Fram

The Transpolar Drift runs east to west

Strait

across the Eurasian Basin from the Siberian

coast out through the western Fram Strait.

Tracer studies show that about 10 percent of

the water in this current comes from rivers,

making it a conveyer belt for any contami-

nants that reach the open ocean through estu-

aries and deltas. The rest of the water comes

from the Bering Strait and from the shelf seas.

The transport takes only five years from the

Ice cover

continental shelves to Fram Strait.

September

the ocean as a layered system; see the diagram

March

Surface water

below.

circulation

Atlantic layer circulation

Number of years

has been traced with radionuclides

x

for sea ice

to exit Fram Strait

Arctic surface water

has a mixed layer and a halocline

Immediately below the Arctic surface layer is

Sea-ice extent in Septem-

the Atlantic layer. This water enters the Arctic

ber and March and the

The Arctic surface water extends to a depth

Ocean at the surface through Fram Strait and

major surface currents

of approximately 200 meters. This water can

the Barents Sea, submerges, circulates around

governing the transport

of sea ice. The numbered

be further subdivided into the polar mixed

the Arctic Basin, and exits back through the

lines show the expected

layer (0 to 50 meters depth) and the halocline

Fram Strait, still submerged.

time in years for the ice

(50 to 200 meters depth). The water comes

Radionuclides from Sellafield, a nuclear

at that location to exit

from rivers, the shelves, and from the Atlantic

reprocessing plant on the northwestern coast

the Arctic Ocean through

Ocean through the Fram Strait. One of the

the Fram Strait.

of England, give a tell-tale sign of water cur-

most important routes is via the North Atlan-

rents. The North Atlantic Current (an exten-

tic Current.

The polar mixed layer is formed in winter

Arctic Ocean

when the ice freezes and excludes brine, and in

summer by melting sea ice and river runoff

10

along the coast. It is the only water within the

4-6 years

4000 km

1-2

Arctic that has direct contact with the atmos-

6-8 years

5000 km

phere and consequently the only water that

can exchange semi-volatile contaminants with

3000 km

the air.

Greenland

50

The halocline is a structurally complex

3-4 years

6000 km

region with water of increasing density. It is

Norway

Time taken for radio-

crucial to the transport of contaminants. Over

2000 km

50

cesium released from

the shelves, it transports water laterally, away

7000 km

4 years

100

3 years

Sellafield to be trans-

from the coast, as heavy, saline water sinks

1000 km

ported to the Arctic

along the bottom.

1000

1 year

Sellafield

Ocean. Bold figures rep-

Atlantic Ocean

resent relative concen-

Away from the shallow coast, the role of the

UK

trations at different

halocline depends on the season. In spring and

points.

summer, it provides a barrier between the sur-

face water and any deeper waters, effectively

sion of the Gulf Stream) transports large quan-

blocking vertical mixing of contaminants. It

tities of warm water from the Gulf of Mexico

also limits the exchange of volatile contami-

via the European coast to the Arctic. Any con-

nants between deeper layers of the ocean and

taminants entering the current from rivers,

the atmosphere. One important transport

ocean dumping, or the atmosphere will be car-

process thus takes place when the halocline

ried along. Radiocesium from the Sellafield

Fridtjof Nansen counted on the Transpolar Drift

and the Barents Sea as the Bering Strait is too

33

`Everywhere, the ice has stopped people in their quest

shallow. The water moves counter-clockwise.

Physical pathways

to reach the North. Only in two cases have the ships

Contaminants enter Arctic deep water

drifted northward once they were stuck in the ice . . . By

mainly by flow of dense water off the shelves.

reading the history of Arctic research, it became clear to

Once there, they can be transported long dis-

me that it would be difficult to capture the secrets of the

tances. One example is the anomalously high

unknown widths of ice by the routes that have been tried.

But where did the road go?'

ratio of cesium-137 to strontium-90, which in

The transpolar drift was documented in the 19th

1979 was observed at the Eurasian Basin flank

century by the Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen

of the Lomonosov Ridge. It represents a signal

with his ship Fram. Three observations gave him the idea

from the Sellafield nuclear reprocessing plant

that water and ice moved according to a particular pat-

on the Irish Sea. The signal was carried either

tern. He had found trees from Siberian forests as drift-

wood on the eastern coast of Greenland. He had also

from Spitsbergen or from the continental slope

found a throwing tool for bird hunting that was typical

off the Barents Sea to the North Pole and then

around the perimeter of the Eurasian Basin in

about 3 years.

The Arctic deep water has an extremely

long residence time, and any contaminants

The Inuit throwing tool

entering this layer might stay in the Arctic for

up to 300 years.

Summary

of Alaskan Inuit on the Greenland shore. But most im-

portant, pieces from the American ship Jeanette had been

Air, water, and ice can carry contaminants over

found on the drift ice south of Greenland. Jeanette had

great distances.

been lost in the ice near the New Siberian Islands on her

In winter, industrial areas of Eurasia are

way north from the Bering Strait. Nothing but drifting

within the Arctic air mass, which provides for

ice could have carried this material over such long dis-

tances. There had to be a current from east to west, and

efficient air transport of particle-bound conta-

Fridtjof Nansen was determined to take advantage of this

minants across the pole. Semi-volatile com-

in his quest to cross the unexplored polar sea. He built a

pounds are carried to the Arctic by cycles of

ship that would survive the crushing forces of the ice and

evaporation, transport, and condensation in a

set out on his journey in the summer of 1893. By mid

fall, the ship was securely lodged in the pack ice north of

multi-hop process. The cold climate traps them

the New Siberian Islands, just as predicted, and it was

more effectively here than anywhere else on

only a matter of time and patience to let the currents do

the globe.

their job. The journey was slow and trusting his theory

Snow, rime ice, rain, and dry deposition

was not always easy. Every sign of progress was noted in

cleanse the air and contaminate the surfaces on

his diary:

`Friday February 16. Hurrah! Our meridian observa-

which they land. The contaminants often end

tion this morning gave 80°1'N. We have come a few min-

up in meltwater that feeds both rivers and the

utes northward since last Friday, even though the wind

ocean surface layer.

has been blowing constantly from the north since Mon-

Rivers process contaminants along their

day. It is very strange. Could it be, as I have thought

routes by sedimentation and resuspension of

myself, observing the skies and the misty air, that it has

been a southerly wind further south, which stops the drift

particles. Lakes, estuaries, and deltas serve as

of the ice in that direction? Or have we finally come

sediment traps and sinks for contaminants.

within an area where a current acts?'

Ice forming in the shelf seas can pick up

Time proved that Fridtjof Nansen was right, that

contaminants from the coastal shelves, and can

there is an east-to-west current. After three years, in

travel far in the Beaufort Gyre and Transpolar

August 1896, Fram was released from the ice as the

Transpolar Drift reached Spitsbergen.

Drift. The ice may release its load of contami-

nants in the biologically productive shelf seas

nuclear reprocessing plant can, for example, be

and in the North Atlantic, where they can be

detected all along the Norwegian coast as well

taken up into the food chain.

as in the Arctic Ocean. Some of the north-

Another important pathway is via ocean

flowing water is returned to the North Atlantic

currents. They act slowly compared with the

in a subsurface flow along the eastern coast of

atmosphere, but take water with water-soluble

Greenland, but a substantial part of this his-

and particle-adsorbed contaminants from dis-

torical discharge now resides in the Arctic

tant industrialized coasts into the Arctic within

Ocean.

a few years, and out again through the East

Greenland Current and the Canadian

Arctic deep water

Archipelago. The sea is the final resting place

has extremely long residence time

for most contaminants.

Modeling is a useful tool for understanding

Arctic deep water extends from 800 meters

contaminant transport. Its importance will

downward and is divided into the Canadian

grow as the basic processes become better

Basin deep water and the Eurasian Basin deep

understood and the models improve.

water. The only inflow is through Fram Strait