4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Chapter 4

Yenisey basin, are heavily industrialized. Industrial

enterprises within these areas include non-ferrous met-

allurgy, pulp and paper manufacture, chemical indus-

tries, and mining, etc., which are recognized as signifi-

cant sources of PTS emissions and discharges.

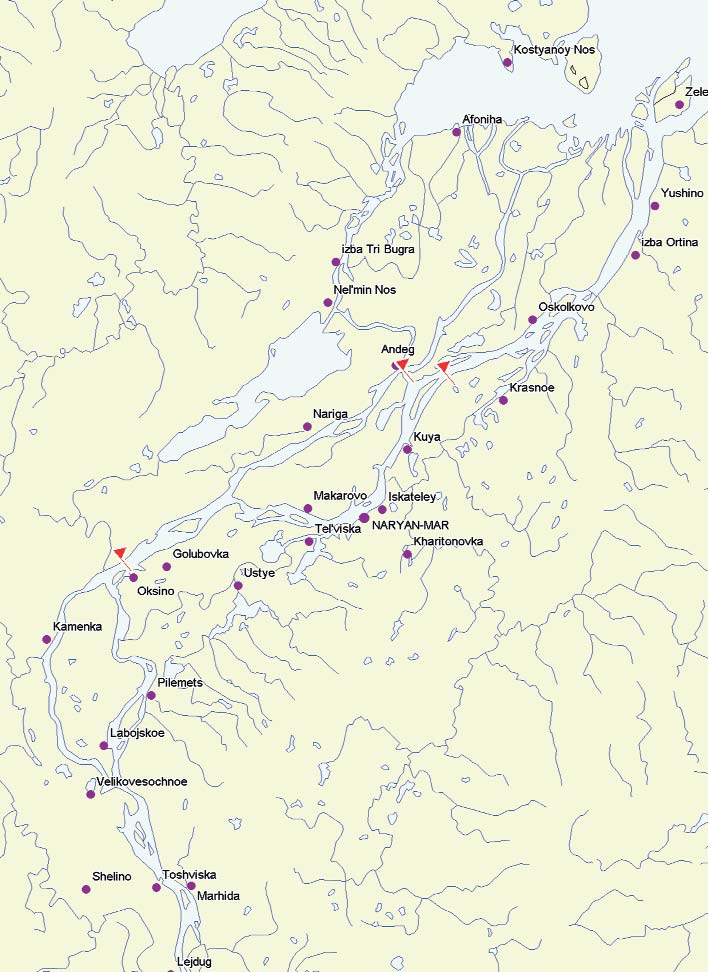

The catchment area of the Pechora river comprises

0.325 million km2 (world ranking 46), with a mean

long-term annual runoff of 141 km3 (world ranking:

30). The Pechora river basin, including the catchments

of its primary and secondary tributaries the Vorkuta,

Bol'shaya Inta, Kolva, Izhma and Ukhta rivers, contain

areas rich in mineral resources, with associated oil, gas

and coal extraction activities.

4.3.2. Objectives and methodology of the study

The objective of this study was to estimate PTS fluxes in

the flows of the Pechora and Yenisey rivers to areas

inhabited by indigenous peoples. Calculations of PTS

loads in the lower reaches of the Pechora and Yenisey

rivers used a range of data, included hydrometric meas-

urements at the closing cross-sections of the

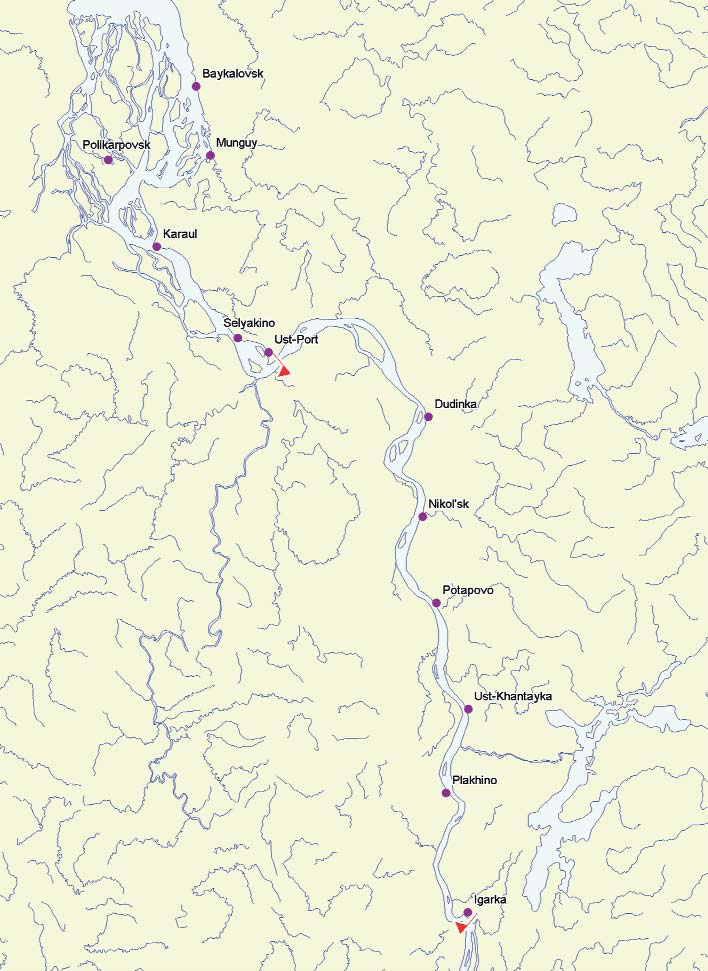

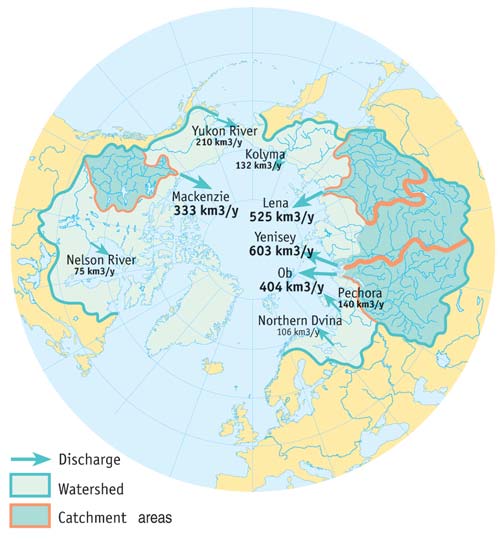

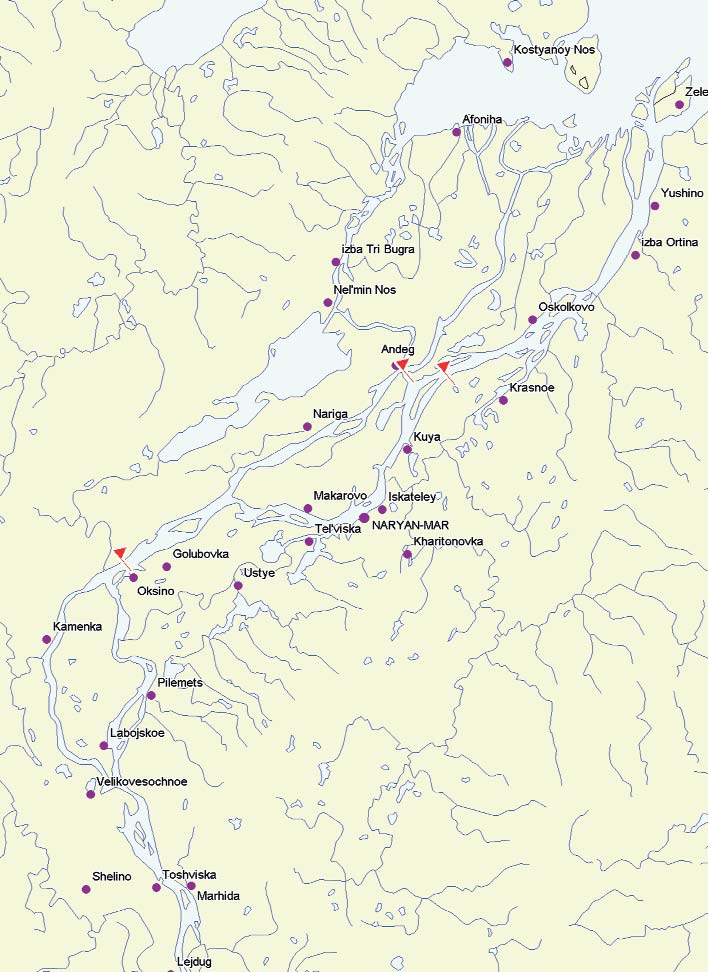

Roshydromet basic hydrological network (in the area of

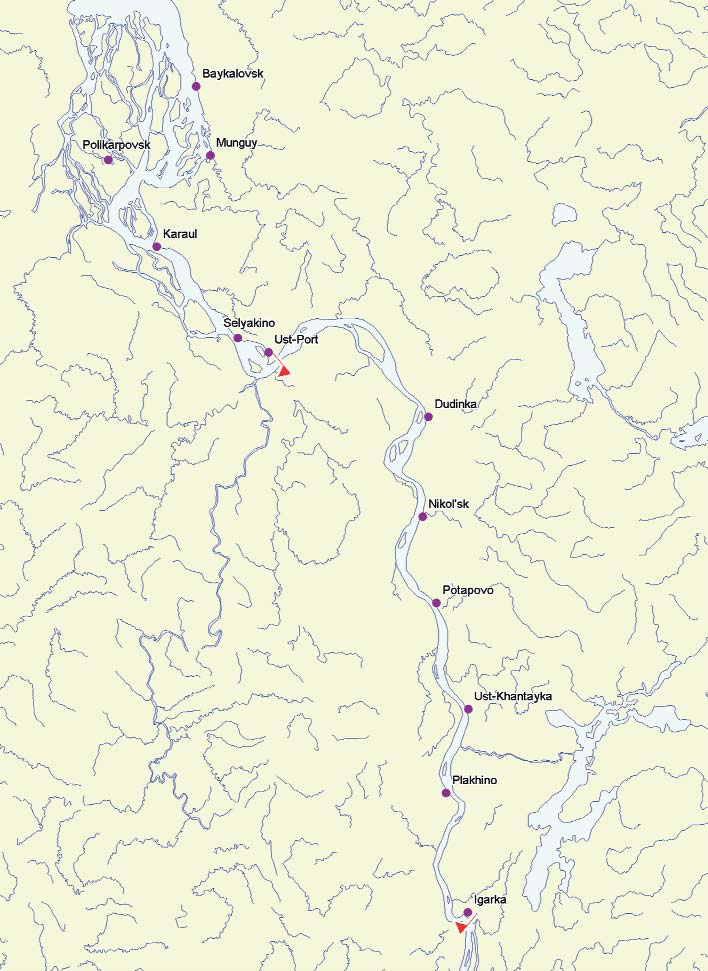

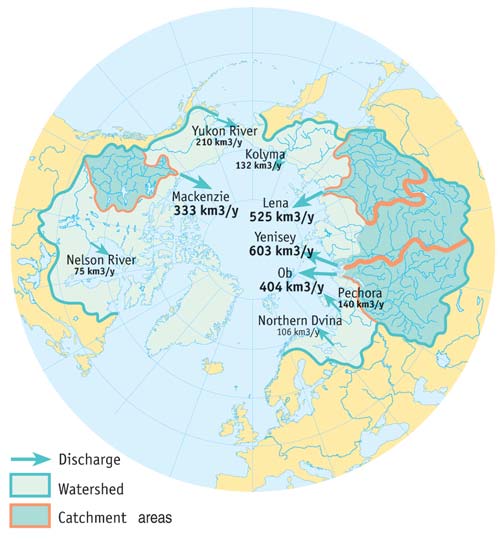

Figure 4.36. Arctic Ocean watershed, and catchment areas

Oksino settlement on the Pechora River and Igarka set-

of the largest Arctic rivers (AMAP, 1998).

tlement on the Yenisey River), and at the lowermost

cross-sections in the delta apexes, upstream of the rivers'

The Yenisey is one of the world's ten largest rivers, with

main branching points (in the vicinity of Andeg settle-

a catchment area of 2.59 million km2 (world ranking: 7)

ment, on both the Large and Small Pechora rivers, and

and mean long-term annual runoff of 603 km3 (world

of Ust'-Port settlement, on the Yenisey River) (Figures

ranking 5) (GRDC, 1994). Its basin incorporates the

4.37 and 4.38). In addition, data were obtained from

East-Siberian economic region, parts of which, particu-

analysis of pooled water and suspended matter samples

larly those located in the upper and central parts of the

collected during periods of hydrological observations.

Figure 4.37. Location of hydrometric cross sections on the Pechora river.

Figure 4.38. Location of hydrometric cross sections on the Yenisey river.

50

Chapter 4

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Hydrometric measurements and water sampling at

each of the cross-sections were carried out according to

internationally accepted methodologies (GEMS, 1991;

Chapman, 1996) during four typical hydrological

water regime phases: during the spring flood fall peri-

od (late-June to early-July), during the summer low

water period (late-July to early-August), before ice for-

mation during the period of rain-fed floods (late-

September to October), and during the winter low

water period (March to April).

During each field survey period, measurements of

flow velocity at various sampling points in the channel

Figure 4.39. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points

profile were made every 6 hours, for 3 days. Water

on the Large Pechora river at the closing cross section near Oksino settlement.

level observations were conducted every 2 hours.

Water sampling was carried out twice during the first

observation day and once a day during the next two

days (a total of 4 single samples for each sampling

point). The volume of each pooled sample was not less

than 20 litres.

Initial data for each water regime phase included:

·

For the Pechora river at the closing cross-section

near Oksino settlement (see Figure 4.39):

15 flow velocity measurements (3 horizontal lev-

els on each of 5 vertical profiles );

measurement of the channel profile;

Figure 4.40. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points on the Large

36 measurements of the river water level;

Pechora river at the downstream cross section near Andeg settlement.

analytical data on PTS concentrations in 11

pooled water and 11 pooled suspended matter

samples collected over a 3-day period in 11 cross-

section segments;

suspended matter concentrations for samples

taken at the flow velocity measurement points,

in 11 pooled water samples, collected over a

3-day period in 11 cross-section segments.

·

For the Large and Small Pechora rivers at the down-

stream cross-sections near Andeg settlement (see

Figures 4.40 and 4.41):

Figure 4.41. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points on the Small

12 flow velocity measurements (3 horizontal lev-

Pechora river at the downstream cross section near Andeg settlement.

els on each of 4 vertical profiles, in both rivers);

measurement of the channel profile;

36 measurements of the river water level;

analytical data on PTS concentrations in 3

pooled water samples and 3 pooled suspended

matter samples from the surface, middle and

near-bottom horizons collected over a 3-day

period;

suspended matter concentrations in 3 pooled

water samples collected over a 3-day period from

the surface, middle and near-bottom horizons.

Figure 4.42. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points on the Yenisey

·

For the Yenisey river at the closing cross-section

river at the closing cross section near Igarka settlement.

near Igarka settlement (see Figure 4.42):

15 flow velocity measurements (3 horizontal lev-

matter samples collected over a 3-day period in

els on each of 5 vertical profiles);

11 cross-section segments;

measurement of the channel profile;

suspended matter concentrations for the flow

36 measurements of the river water level;

velocity measurement points in 11 pooled water

analytical data on PTS concentrations in 11

samples, collected over a 3-day period from 11

pooled water samples and 11 pooled suspended

cross-section segments.

51

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Chapter 4

4. calculation of partial and total mean daily fluxes of

PTS in dissolved form during the typical water

regime phases;

5. calculation of partial and total mean daily fluxes of

PTS in suspended matter during the typical water

regime phases.

The river channel profiles used in the hydrometric

measurement cross-sections were evaluated on the

basis of depth measurements and water level observa-

tions. Depth measurements (at various points across

Figure 4.43. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points on the Yenisey

the channel) were taken once, prior to the start of the

river at the downstream cross section near Ust' Port.

3-day observation period. Water level observations

were then made every two hours for three days. To

·

For the Yenisey river at the downstream cross-sec-

model the channel profile, an averaged single value

tion near Ust'-Port settlement (see Figure 4.43):

for water level above the original gauging station

15 flow velocity measurements (3 horizontal lev-

datum was applied across the river cross section.

els on each of 5 vertical profiles);

Thus, 16 profiles were evaluated (one for each of the

measurement of the channel profile;

four cross-sections in each of the four water regime

36 measurements of the river water level;

phases) on the basis of average `effective' cross-sec-

analytical data on PTS concentrations for 3

tional areas during the 3-day observational periods.

pooled water samples and 3 pooled suspended

Ice thickness was taken into account in the construc-

matter samples from the surface, middle and

tion of the channel profile during the winter low

near-bottom horizons collected over a 3-day

water period.

period;

suspended matter concentrations in 3 pooled

The cross-section areas were subdivided into seg-

water samples collected over a 3-day period from

ments corresponding to the points of flow velocity

the surface, middle and near-bottom horizons.

measurements and sampling. The profile schemes

During the winter low water period, ice thickness was

for each cross-section showing segments are pre-

also measured at each of the cross-sections.

sented in Figures 4.39 to 4.43. The numbers of seg-

ments coincides with the number of observations

For calculations of mean monthly and annual PTS flux-

points.

es through the closing and downstream cross-sections

for the year in which the observations were made, oper-

In order to calculate partial and total mean daily PTS

ational data consisting of water discharge measure-

fluxes in dissolved and suspended form during the typ-

ments at river cross-sections in the area of Oksino and

ical water regime phases, the following assumptions

Igarka settlements were used. These data were provid-

were made:

ed by the Northern (Pechora river) and Central

·

At the closing cross-section, within a given segment,

Siberian (Yenisey river) Territorial Branches of

the PTS concentrations in water and suspended

Roshydromet.

matter do not vary over the time period being rep-

resented, and are equal to the measured concentra-

In order to calculate mean monthly and annual PTS

tion at the corresponding observation point.

fluxes through the closing cross-sections of the rivers for

·

At the downstream cross-section, within the com-

a year with `average' runoff, and to assist in the prepara-

bined segments identified, the PTS concentrations

tion of a brief review of the inter-annual variability in

in water and suspended matter do not vary over the

water runoff via the Pechora and Yenisey rivers, pub-

time period being represented, and are equal to the

lished hydrographical data from 1932-1998, obtained

measured concentrations in the corresponding

from the Roshydromet hydrological network, were used.

pooled samples.

·

Any PTS that were either not found in any of the

Calculation of mean daily PTS fluxes over the 3-day

samples during the entire observation period, or

observation periods was undertaken in several stages:

were found in less than 10% of the total number of

1. evaluation of the river channel profiles at the cross-

samples collected at both the closing and the more

sections where hydrometric measurements were

downstream cross-sections of a river, were excluded

taken;

from PTS flux calculations for the given hydrologi-

2. division of the cross-sectional area into segments,

cal phase.

for calculation of partial discharges and PTS fluxes;

·

Edge effects are not taken into account.

3. calculation of the partial mean daily water and sus-

pended matter discharges (for each segment iden-

An assessment of mean monthly PTS flux (µy) in dis-

tified) and total water and suspended matter dis-

solved and suspended form was made according to the

charges (for the whole cross-section) during each of

calculation method proposed by E.M.L. Beal (Frazer

the typical water regime phases;

and Wilson, 1981).

52

Chapter 4

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

(4.1)

where:

µx mean daily water discharge for the given month

(L/day);

my mean daily flux of the substance under considera-

tion in the dissolved or suspended forms (kg/day),

obtained for a 3-day observation period;

mx mean daily water discharge (L/day), obtained for

a 3-day observation period;

n number of observation days in a month (using

our assumptions three).

and:

Xi, Yi values of the water discharge and flux of the sub-

stance under consideration for each specific day when

measurements were conducted.

In our case Yi=my and Xi=mx, as the concentration of

suspended matter and PTS concentrations were deter-

mined from a single integral sample collected during

the 3-day observation period and the water discharges

were calculated on the basis of the average flow veloci-

ty for a 3-day period.

In this case, equation (1) above for the calculation of

mean monthly PTS flux can be simplified to:

(4.2)

In applying this, the following assumptions were

adopted:

·

Values of my and mx were assumed to be constant

for the months which fall within each hydrological

season: i.e., May-July (spring flood); August-

September (summer low water period); October

(period before the onset of ice formation);

Table 4.12. PCB flux (kg/y) at the closing cross sections of the Roshydromet

November-April (winter low water period).

network, calculated for the period of observations (2001 2002), and for the long term

·

The ratio of the PTS fluxes in dissolved and particu-

mean annual water discharge.

late associated phases is constant inside the cross-sec-

tion and during the hydrological season represented.

·

For the Pechora, mean monthly water discharges at

·

The ratio of the PTS fluxes in dissolved and partic-

the Andeg cross-section were assumed to be equal to

ulate associated phases during the spring freshet is

the discharges at the Oksino cross-section.

assumed to be equal to the ratio during periods of

·

For the Yenisey, mean monthly water discharges at the

low discharge.

Ust'-Port cross-section were assumed to be 3% higher

than the discharges at the Igarka cross-section.

As mentioned above, mean monthly water discharges at

the closing cross-sections of the Pechora and Yenisey

Analytical studies covered the whole range of PTS includ-

rivers (near Oksino settlement and Igarka, respectively)

ed within the project scope, with the exception of dioxins

for both the observation year and an `average' water dis-

and brominated compounds, which were excluded due

charge year, for use in the calculations, were provided by

to their extremely low levels in abiotic freshwater environ-

Roshydromet. For the two downstream cross-sections,

ments. However, analysis of samples collected during field

similar data were not available. Consequently, the follow-

work also showed that levels of toxaphene compounds

ing assumptions were adopted for calculation purposes:

in all samples from the Pechora and Yenisey were lower

53

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Chapter 4

than effective detection limits (0.05 ng/L for water,

Although it is difficult to make a definite conclusion

and 0.01 ng/mg for suspended matter), therefore toxa-

regarding the cause of this peak appearance, the fol-

phene was also excluded from the assessment of fluxes.

lowing information should be noted:

·

the peak was observed not only during the summer

4.3.3. Overview of the assessment results

low water period, when it was detected for the first

time, but also during the period before ice forma-

PCB

tion in October (Figure 4.62);

Estimated PCB fluxes via the Pechora and Yenisey

·

the peak is due to increased fluxes in PCB con-

rivers are presented in Table 4.12. It is worth noting

geners associated with suspended matter, with dis-

that the estimated fluxes of specific PCB congeners

solved forms showing practically unchanged fluxes;

through both the closing cross-sections of the regular

·

compared to the spring flood peak, which, as in the

hydrometric network and the downstream cross-sec-

case of the Pechora, is a result of fluxes of tri- and

tions are very similar (Figure 4.44). Based on this infor-

tetra-chlorobiphenyls, the second flux peak has a

mation, the overview of assessment results for other

higher contribution of penta- and hexa-chloro-

contaminant groups, below, focuses mainly on fluxes in

biphenyls, particularly CB118 and CB138 (Figure

the closing cross-sections of the rivers.

4.46).

Figure 4.46.

Monthly fluxes (kg)

of selected PCB congeners in

(a) dissolved

(b) suspended form

in the Yenisey river.

a

Figure 4.44. Estimated fluxes (kg/y) of PCB congeners at the closing (Oksino)

and downstream (Andeg) cross sections of the Pechora river.

The total PCB flux in the Pechora river consists almost

entirely of tri- and tetra-chlorobiphenyls. Fluxes of the

heavier PCB congeners are negligible. This is consis-

tent with information presented to the OSPAR

Commission by Sweden (Axelman, 1998).

The structure of PCB fluxes in the Yenisey river are

b

more complex. As expected, peak PCB fluxes in both

rivers coincide with springtime peaks in water dis-

charge, which occur later in the lower Yenisey than in

the lower Pechora. However, flux values for the Yenisey

river also exhibit a distinct second peak in the late sum-

mer-autumn period (Figure 4.45).

Figure 4.45.

Monthly fluxes (kg) of PCB

in the Pechora and Yenisey

rivers.

Two possible explanations for the second peak are:

·

instrumental/procedural errors during analysis of

the samples;

Table 4.13. Fluxes of polychlorinated benzenes (kg/y) in flows of the Pechora

·

accidental PCB release from some unknown pollu-

and Yenisey rivers, calculated for the period of observations (2001 2002),

tion source.

and for the long term mean annual water discharge.

54

Chapter 4

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

This evidence, whilst indirect, argues for the likely

explanation being an accidental PCB release from a

non-identified local source. However, in case of a short-

term release, estimation of the annual flux based of

this data can be overestimated.

Polychlorinated benzenes

Estimates of annual fluxes of polychlorinated benzenes

(PCBz) in the flows of the Pechora and Yenisey rivers

are presented in Table 4.13. As expected, hexa-

chlorobenzene (HCB) is the main compound in this

contaminant group, with relatively high fluxes in both

rivers. Although tetra-chlorinated benzenes (TeCBz)

have occasionally been found in both water and sus-

pended matter of both rivers, their concentrations

were close to detection levels, and as such they cannot

be considered contaminants that pose a significant

threat to either the aquatic environment or humans.

Seasonal distribution of fluxes exhibit the a typical pat-

tern of a peak during the spring flood period (Figure

4.47).

Figure 4.47. Monthly fluxes (kg) of QCB and HCB

in the Pechora river.

Table 4.15. Fluxes of DDT compounds (kg/y) in flows of the Pechora

and Yenisey rivers for 2001 2002.

HCH compounds increase downstream in the Pechora

river, while the Yenisey shows the opposite trend. A pos-

sible explanation is that the downstream section of the

Pechora rivers shows the impact of local HCH usage,

while HCH fluxes in the lower Yenisey river are the

result of long-range transport alone, and thus the down-

stream section of the river has lower loads due to self-

purification processes in the aquatic environment. It

should be noted however that in case of short-term envi-

ronmental releases annual fluxes can be overestimated.

(b) DDTs

Fluxes of DDTs in flows of the Pechora and Yenisey

Table 4.14. Fluxes of HCH compounds (kg/y) in flows of the Pechora

rivers show similar trends as for HCHs (Table 4.15),

and Yenisey rivers for 2001 2002.

with a strong increase in concentrations between the

Oksino and Andeg cross-sections of the Pechora, and a

Organochlorine pesticides and their metabolites

decrease between the Igarka and Ust'-Port cross-sec-

tions of the Yenisey. This can be explained by a large

(a) Hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH)

local input of DDT into the lower part of Pechora, par-

Data on HCH fluxes in the Pechora and Yenisey rivers

ticularly during the spring flood period (Figure 4.48),

are presented in Table 4.14. For both rivers, total HCH

whereas in the Yenisey, the contamination is the result

fluxes are dominated by - and -HCH isomers, with -

of long-range transport of contaminants in the Yenisey,

HCH the most prevalent. However, the two rivers do

with fluxes decreasing downstream due to self-purifica-

not show consistent trends between the closing cross-

tion. This conclusion is supported by the significant

sections of the regular observation network and the

change seen in the composition of the total DDTs flux

more downstream cross-sections, established close to

at the downstream Andeg cross-section when com-

areas inhabited by indigenous population. Fluxes of all

pared to Oksino. At Andeg, the proportion of the DDT

55

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Chapter 4

Figure 4.50.

DDT concentrations (ng/mg)

in suspended matter of the

Pechora river at the Andeg

cross section (PA 1: surface

layer, PA 2: middle layer,

PA 3: bottom layer)

(see Figures 4.40 and 4.49).

(c) Other chlorinated pesticides

Figure 4.48. Monthly fluxes (kg)

of DDT in the Pechora river.

Other chlorinated pesticides included in the priority

list of PTS considered in the project were either found

component is far greater (Figure 4.49). Considering

only at levels below detection limits, or had fluxes that

that the absolute value of DDD, which is a dechlori-

would not be expected to have any noticeable impact

nated DDT analog in the technical DDT mixture

on the health of indigenous human populations (Table

(AMAP, 1998), also shows an almost three-fold

4.16).

increase, it is reasonable to assume that the DDT flux

increase is due to fresh local input of DDT. For the

Yenisey river, the DDT flux composition did not alter

between the two cross-sections. In this case, like in case

of HCH, annual fluxes can be overestimated.

It should be noted that the increase in DDT flux at the

Pechora, Oksino

Pechora, Andeg

Table 4.16. Fluxes of other chlorinated pesticides (kg/y) in flows of the Pechora

and Yenisey rivers for 2001 2002.

Yenisey, Igarka

Yenisey, Ust-Port

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

DDT

DDE

DDD

The list of PAHs included in the scope of the prelimi-

nary assessment of riverine fluxes included 20 com-

Figure 4.49. Composition of total DDT fluxes in the Pechora and Yenisey rivers.

pounds. Annual fluxes of 10 PAHs in the Pechora and

Yenisey are presented in Figures 4.51 and 4.52, respec-

Andeg cross-section is mostly determined by an

tively. However, fluxes of several PAHs could not be

increase in its suspended form. Data quality can be ver-

assessed, as their concentrations in water and suspend-

ified from the comparability of data obtained for the

ed matter in both rivers were below detection limits.

suspended matter flux in different layers of the Andeg

These were:

cross-section (Figure 4.50). The ratio of o,p'-DDT to

acenaphthene, benzo[a]anthracene,

p,p'-DDT in the surface, middle and bottom layers of

benzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[e]pyrene, perylene,

the river flow remains constant, however, the surface

benzo[k]fluoranthene, benzo[a]pyrene,

layer shows lower levels of DDT when compared to the

dibenzo[a,h]anthraceneindeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene,

middle and bottom layers.

and benzo[ghi]perylene.

56

Chapter 4

4.4. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

In both rivers, PAH fluxes are dominated by the more

PAHs (fluoranthene and pyrene). Increase in fluxes of

soluble 2-cyclic PAHs (naphthalene, 2-methylnaphtha-

these less readily transported 4-cyclic PAHs provides

lene, biphenyl) and, to certain extent, 3-cyclic PAHs

additional evidence of local pollution sources between

(fluorene, phenanthrene). At the downstream Ust'-

the Oksino and Andeg cross-sections of the Pechora

Port cross-section of the Yenisey river, PAH fluxes are

river.

significantly lower. This confirms an absence of addi-

tional PAH sources between the two cross-sections

Heavy metals.

along this part of the river. However, fluxes of some

Data on annual fluxes of heavy metals that were includ-

PAHs at the downstream Andeg cross-section of the

ed in the study (lead, cadmium, and mercury) are pre-

Pechora river are significantly higher than at the

sented in Table 4.17.

upstream Oksino cross-section. This is true not only for

2- and 3-cyclic PAHs, such as 2-methylnaphthalene, flu-

(a) Lead

orene and phenanthrene, but also for the heavier

The intra-annual distribution of lead fluxes in flows of

the Pechora and Yenisey rivers are presented in Figures

4.53 and 4.54. For both rivers, peaks of lead fluxes coin-

cide with the peak of the spring flood. It is noticeable

that the composition and annual distribution of lead

flux in the Yenisey river has a more complicated pat-

tern than that of the Pechora river. During low-water

periods, and particularly during the ice cover season,

lead flux at both the Igarka and Ust'-Port cross-sections

is dominated by the dissolved form of the metal, with

levels almost twice as high at the upstream cross-sec-

tion. However, during the flood period, the flux at the

Table 4.17. Fluxes of heavy metals (t/y) in flows of the Pechora and Yenisey rivers

Ust'-Port cross-section is significantly higher than at

for 2001 2002.

Igarka, and is mostly due to suspended forms of lead.

Figure 4.51.

Estimated fluxes (t/y)

of PAHs in the flow

of the Pechora river.

Oksino

Andeg

Figure 4.52.

Estimated fluxes (t/y)

of PAHs in the flow

of the Yenisey river.

Igarka

Ust-Port

57

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Chapter 4

during the spring flood period (Figures 4.58 and 4.59).

The Yenisey river mercury flux almost totally consists of

suspended forms of the metal. The composition of the

mercury flux of the Pechora river is more complicated,

and differs between the Oksino and Andeg cross-sec-

tions (Figure 4.60). Total flux at the upstream Oksino

cross-section is higher relative to that at Andeg (Figure

4.61). During the spring flood period, suspended forms

of mercury are dominant in the flux, particularly at

Figure 4.53. Monthly fluxes (t)

of lead in the Pechora river.

July

September

Figure 4.54. Monthly fluxes (t)

of lead in the Yenisey river.

This suggests that during the ice cover season, lead flux

is almost totally determined by long-range transport of

the more mobile dissolved form of lead, from industri-

alized regions in the central part of the Yenisey basin;

whereas, during the flood period, lead flux is dominat-

ed by local runoff from the area between Igarka and

November

April

Ust'-Port, which can be significantly affected by the

dissolved

suspended

Norilsk industrial region.

Figure 4.56. Seasonal changes in the ratio of dissolved and suspended fluxes

of cadmium in the Pechora river flow.

(b) Cadmium

Compared to the other PTS, the difference in cadmi-

um fluxes seen in the flows of the Pechora and Yenisey

rivers is much more pronounced (Figure 4.55). It is

also notable that the composition of cadmium fluxes in

the two rivers are different (Figures 4.56 and 4.57). The

Pechora river flux has a much greater proportion of

the suspended form of cadmium, particularly during

the spring flood period. During the ice cover season,

this difference is not so noticeable. This could be

explained by the higher sediment load of the Pechora,

July

September

compared to the Yenisey.

Figure 4.55.

Monthly fluxes (t)

of (dissolved+suspended)

cadmium in the Pechora

and Yenisey rivers.

November

April

(c) Mercury

In general, the intra-annual distribution of mercury

dissolved

suspended

fluxes in the Pechora and Yenisey correspond to the

Figure 4.57. Seasonal changes in the ratio of dissolved and suspended fluxes

respective river hydrographs, with the highest fluxes

of cadmium in the Yenisey river flow.

58

Chapter 4

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

a

July

b

Figure 4.58. Monthly fluxes (kg)

of mercury in the Pechora river.

Figure 4.59.

Monthly fluxes (kg)

of mercury in the Yenisey

river.

a

September

b

Andeg. During low water periods, the dissolved pro-

portion of the total mercury flux is larger, amounting

to 74% of the total at Andeg during the ice cover sea-

son. It should be also noted that during this period, the

dissolved flux at these two cross-sections is fairly con-

stant (17-20 kg), while suspended flux is noticeably

lower at Andeg than at Oksino (Figure 4.61); this can

be explained by sedimentation processes.

a

November

b

The significant difference in the composition of mer-

cury fluxes in the Pechora and Yenisey rivers may be

explained by differences in their water composition.

Concentrations of total organic matter in the Pechora

are almost twice as high as those in the Yenisey, reach-

ing 13-15 mg/L Total Organic Carbon (TOC), 98% of

which is in dissolved form (Kimstach et al., 1998). As

TOC in natural waters is mostly represented by humic

and fulvic acids, which form strong complexes with

mercury, the trends in the Pechora mercury fluxes are

understandable.

a

April

b

dissolved

suspended

4.3.4. Conclusions

1. In general, PTS fluxes in the Pechora and Yenisey

Figure 4.60. Ratio of dissolved and suspended fluxes of mercury

river flows correspond to seasonal river discharges.

at (a) the Oksino and (b) the Andeg cross sections of the Pechora river

Highest fluxes usually coincide with spring peak

discharges.

2. Among the chlorinated persistent organic pollu-

tants, the highest fluxes are observed for PCBs,

HCH and DDTs. The amounts of these contami-

nants transported by river flows to areas inhabited

by indigenous peoples are such that they could con-

tribute to risks to human health.

3. Levels of other chlorinated organic pollutants are

Oksino

Andeg

either below detection limits, or their fluxes are not

dissolved

suspended

sufficiently high to represent a significant risk to the

Figure 4.61.

indigenous population.

Mercury fluxes (kg) at two cross sections in the Pechora river

in April 2002

59

4.4. Local pollution sources in the vicinities of indigenous communities

Chapter 4

4. PCB fluxes are mostly in the form of tri- and tetra-

North (RAIPON), and also from expert estimates of

chlorobiphenyls. Fluxes of the heavier PCB con-

PTS release resulting from use of organic fuel (as this

geners are practically negligible.

information is not included in official statistical data

on PTS emissions). This latter source of atmospheric

5. HCH and DDT fluxes in the Yenisey river flow are

PTS is important for pollutants such as heavy metals,

the result of long-range transport. In the Pechora

PAHs, and dioxins. It should be mentioned that in

river, local sources may contribute to the fluxes of

Russia, dioxin emissions have not been recorded and,

HCH and DDT in the lower reaches of the river.

among PAHs, only benzo[a]pyrene emissions are

DDE to DDT ratios indicates that the increased

recorded.

DDT flux in the lower part of the river may be

caused by fresh use of this pesticide. However, tak-

Under the study, expert estimates were made for emis-

ing into account possible short-term environmental

sions of the following PTS: lead, cadmium, mercury,

release of these substances, their annual fluxes can

benzo[a]pyrene, benzo[k]fluoranthene, indeno[1,2,3-

be overestimated.

c,d]pyrene, and dioxins. These estimates were made

using statistical data relating to consumption of the var-

6. Fluxes of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

ious kinds of fuels and associated emission factors (for

in both rivers consist mostly of 2- and 3-cyclic com-

the amount of contaminants released to the atmos-

pounds. In addition to contamination through

phere per tonne of a specific fuel). Emission factors

long-range transport, the lower reaches of the

were determined either in accordance with existing

Pechora river may also be affected by local sources

Russian methodology, or by adapting Western Euro-

of PAHs, which contribute some heavier com-

pean emissions factors to take account of Russian tech-

pounds.

nologies.

7. Fluxes of heavy metals (lead, cadmium and mercu-

Statistical data were provided by the State statistic

ry) in the flow of the Yenisey river, are the result of

offices of the relevant administrative territories of the

local contamination, in addition to contamination

Russian Federation, environmental protection author-

from long-range transport, particularly during the

ities, and reports by the Russian Federation's State

spring flood period. This can be explained by the

Committee for Statistics (Goskomstat).

influence of pollution from the Norilsk industrial

complex.

Regional Branches (Committees) of the Russian

Federation's Ministry of Natural Resources were

4.4. Local pollution sources

responsible for the initial collection and processing of

in the vicinities of indigenous communities

data and information. The inventory of pollution

sources was based upon the following sources of infor-

4.4.1. Introduction

mation:

The main objectives of undertaking an assessment of

local pollution sources were to determine their role in

State Statistic Reports on emissions of gaseous

general environmental pollution, in the contamina-

pollutants discharges of waste waters, and solid

tion of traditional food products and, accordingly, to

waste from industrial, municipal and agricultur-

determine their influence on human health. For inven-

al enterprises and transport;

tory purposes, `local sources' were taken to mean

Ecological passports of industrial enterprises;

sources within an approximate maximum distance of

Reports on environmental protection activities

100 km of sites of residence of indigenous peoples.

of the local environmental protection authori-

Specific boundaries for inventory zones, however, were

ties, sanitary-epidemiological control services,

defined more exactly in each case by taking account of

agricultural administrative authorities, and

local conditions (dominating winds, river flows and the

other information sources (Murmansk, 1991-

scale of regional sources, etc.). As some of the pilot

2000; Murmansk, 1996-2000; Murmansk, 2001;

study areas within the project are affected by pollution

Murmansk, 1994-2000; Nenets, 1998; Nenets,

which originates from large industrial complexes locat-

1999; Nenets, 2001);

ed in their vicinity, the pollution source inventory

Annual reports and reviews of Federal Ministries

included such towns as Apatity, Monchegorsk,

and Departments (MNR, 2001; Roshydromet,

Olenegorsk, Revda, and Kirovsk (in Murmansk

1995-2000);

Oblast); Nar'yan-Mar (in the Nenets AO); Norilsk

Other relevant official sources and literature.

(located in the Taymir AO, but under the administra-

tive authority of Krasnoyarsk Krai); and Anadyr (in the

It is necessary to mention, however, that there was

Chukotka AO).

variation in the completeness and volume of infor-

mation provided by the various regions for the inven-

The assessment was based on official data relating to

tory, due to different technical, organizational, and

PTS emissions, obtained from the various administra-

other aspects of the relevant local services. Due to

tive territories and regions, representatives of the

this, a certain amount of data are derived from

Russian Association of Indigenous People of the

expert estimates.

60

Chapter 4

4.4. Local pollution sources in the vicinities of indigenous communities

Table 4.19. Total air emissions of pollutants (thousand tonnes) from major

industrial pollution sources in the inventory area in Murmansk Oblast, 2002,

and their percentage contribution to emissions from the

corresponding cities/districts.

Table 4.18. Industrial air emissions of major contaminants in the cities

and districts of the Murmansk Oblast in 2002, thousand tonnes (NEFCO, 2003).

4.4.2. Murmansk Oblast

4.4.2.1. General description

The inventory of PTS sources covered the territory

Table 4.20. Wastewater discharges (million m3) from selected large industrial

within a radius of at least 100 km of the settlement of

enterprises in 2002, and associated discharges (tonnes) (NEFCO, 2002).

Lovozero. It includes the cities of Monchegorsk,

Olenegorsk, Apatity, Kirovsk, and Revda.

These include the Nickel and Copper Combined

Smelter JSC GMK Pechenganikel, in the city of

Murmansk Oblast is one of the largest and most eco-

Zapolyarny and the town of Nikel; the Iron Ore

nomically developed regions of Russia's European

Concentration Plant JSC Olkon, in the city

North. Almost the entire territory lies to the North of

of Olenegorsk; the Nickel and Copper Combined

the Arctic Circle. The population amounts to 958,400

Smelter JSC Severonikel, in the city of Monche-gorsk;

residents, of whom 91.7% are urban and 8.3% percent

the Mining Plant Apaptit JSC, in the cities of Kirovsk

are rural. The northern indigenous peoples, mostly

and Apatity; the Iron Ore Kovdor Mining and

Saami, amount to 0.2% of the total population.

Concentration Plant JSC, and the Concen-

tration Plant Kovdorslyuda JSC, in the city of Kovdor;

The economy of Murmansk Oblast is mainly oriented

and the rare metals extraction and concentration plant

towards the extraction and reprocessing of natural

Sevredmet JSC, in the settlement of Revda. The contri-

resources. The region produces 100% of Russia's

butions made by the large enterprises located in the

apatite concentrate, 12% of iron-ore concentrate, 14%

inventory area to total air emissions in the correspon-

of refined copper, 43% of nickel, and 14% of fish food-

ding city/district are presented in Table 4.19.

stuffs. Concerning production industries, 90% of the

gross regional product is created by primary industrial

Surface water bodies located close to settlements and

enterprises.

industrial complexes have a high degree of pollution,

as determined by their acidification (pH) and levels of

Estimates of emissions of general air pollutants (SO2,

fluorine (F), aluminium (Al), iron (Fe), and man-

NOx, CO, and dust) from industries in the region are

ganese (Mn), which all exceed maximum permissible

presented in Table 4.18. Although these pollutants are

concentrations. Data on wastewater discharges from

not representative of any specific PTS, they do charac-

the selected large industrial enterprises in the survey

terize levels of general environmental pollution, and

area are presented in Table 4.20.

thus are related to pollution impacts on human health.

As shown, industrial enterprises located in the vicinity

Monchegorsk area

of the study area, which is densely populated by the

A zone of `extremely unfavorable environmental pol-

Saami people, emit a significant part of the total indus-

lution' lies within the area influenced by the cities of

trial air emissions in Murmansk Oblast, particularly

Monchegorsk and Olenegorsk. This zone occupies

NOx and dust.

an area of about 1400 km2, and has the form of an

ellipse with the city of Monchegorsk at its epicenter

Mining and processing plants provide the basis for the

and its long axis extending 48-50 km to the south

economies of the majority of the regions large towns

(due to the prevailing wind direction). In the north,

and cities where a third of the Oblast's population live.

the zone extends as far as the city of Olenegorsk,

61

4.4. Local pollution sources in the vicinities of indigenous communities

Chapter 4

incorporating the urban agglomeration, and in the

km2), hazardous (200 km2), moderately hazardous

south, it extends to Viteguba. The Monchegorsk

(240 km2) and acceptable (435 km2) with respect to

area is characterized by extreme levels of annual

pollution of soils. The total area of polluted land

deposition of nickel (Ni) and copper (Cu) (115.9

amounted to 565 km2. With increasing distance from

and 136.5 kg/km2, respectively). Cadmium levels in

the industrial pollution sources and the Lovozero

the surface geological horizon in this area are five

Massif (an ore-rich feature, which itself creates a natu-

times higher than the background level for the

ral geochemical anomaly), a drastic reduction in the

region. These figures confirm the high environmen-

content of all polluting substances in soils, with the

tal impact of the Monchegorsk `Severonickel' com-

exception of sulphur, can be observed. Sulphur con-

bined smelter.

tent in soils has a patchy occurrence, with localised

`hotspots', usually seen in remote places, far from the

Kirovsk Apatity

sources of gas and dust emissions.

This area is located within the limits of the Khibiny

Massif, which is a natural geochemical anomaly with

As in the case of soils, the highest pollution levels in

respect to the vast number elements and the unique

mineral bottom sediments of water bodies are

deposits of apatite and nepheline ores. `Apatit' JSC,

observed in the area of the Lovozero Massif and its

which processes and enriches deposits of apatite and

spurs, where the main mining and concentration

nepheline ores, is considered as the main pollution

plants are located. Similar to soils, the maximum levels

source for this area. The plant is one of the world's

of toxic elements (for the same group of main pollu-

biggest manufacturers of raw phosphate used in the

tants) found in bottom sediments generally corre-

production of mineral fertilizers. `Apatit' JSC is a huge

spond to the level of emissions. Contrary to its distri-

mining and chemical complex which currently

bution in soils, however, maximum concentrations of

includes four mines, a concentration plant, railway

sulphur are found in the bottom sediments of water

facilities, an automobile workshop, and about thirty

courses in urban areas.

other service workshops.

4.4.2.2. Inventory of PTS pollution sources

Since opening, the `Apatit' plant has extracted and

transported more than 1.4 x 109 tonnes of ore to the

Pesticides

concentration plant, and produced about 520 million

According to data provided by the Murmansk

tonnes of apatite and more than 52 million tonnes of

Territorial Station for Plant Protection, chlorinated

nepheline concentrates. The concentrates also con-

pesticides that are the main subject of the PTS inven-

tain fluorine, strontium oxide, and rare-earth ele-

tory have not been used, and are not currently used, in

ments, which may be separated as individual products

Murmansk Oblast. Other types of pesticides used over

during processing. Nepheline concentrate is used as a

the last twenty years, according to the information

raw material for producing alumina, and in the glass

available from this office, are shown in Table 4.21. The

and ceramic industries. It is also used as a raw materi-

quantity of pesticides used on open ground varies from

al for producing soda, potash, cement, and other

tens to a few hundred kilograms in weight, because the

products.

area of agricultural land is limited.

Lovozero Revda

This area is located in a zone of heavy metal contami-

nation created by the `Severonickel' combined

smelter. The largest local pollution source is the rare

metals combined enterprise JSC `Lovozero GOC' (for-

merly known as `Sevredmet'), located in the settle-

ment of Revda. The enterprise consists of two mines

(Karnasurt and Umbozero) and two concentration

plants. Tailings and rocks left after drifting and strip-

ping are stockpiled in surface dumps and storage sites.

Mining and drainage waters are discharged into sur-

face water bodies.

The river with the highest anthropogenic load is the

Sergevan, which receives untreated and poorly-treated

mining, filtration, and domestic wastewaters from the

Karnasurt mine and concentration plant. Fluorine, sul-

phates, and nitrates are typical constituents of the min-

ing waters. Environmental and geochemical mapping

of the northern part of the Lovozero Massif which was

carried out between 1993 and 1996, (Lipov, 1997),

Table 4.21. Use of pesticides in 1990 2000 in the Murmansk Oblast inventory area,

depicted areas classed as extremely hazardous (125

data from the Murmansk Territorial Station for Plant Protection.

62

Chapter 4

4.4. Local pollution sources in the vicinities of indigenous communities

Such agricultural enterprises as `Industria', `Revda',

which, according to available information, contain no

and `Monchegorsky' and "POSVIR", store pesticides in

synthetic PCB additives. The PCB-containing trans-

standard or customized warehouses, which are regis-

former fluid `Sovtol' (total amount: 35.92 t) is used

tered by the sanitary and epidemiological surveillance

only in 13 transformers of the TNZ type at `Apatit' JSC.

bodies. The agricultural enterprise `Tundra' has

The inventory did not find any other enterprises with-

received one-off permissions for delivery and use of

in Murmansk Oblast that use PCB-containing fluids in

plant protection chemicals.

any type of electric equipment.

It should be noted that the table contains data on her-

At the same time, it is notable that of the 180000 t of

bicides only, and that no other types of pesticides, par-

PCB that was produced in the former USSR/Russia,

ticularly insecticides, are included. It is, therefore, like-

53000 t were in the form of the product `Sovol' that was

ly that the data and information provided by the

used in the production of varnish and paint (37000 t)

regional authorities responsible for pesticide use and

and lubricants (10000 t). In addition, ca. 5500 t were

handling is incomplete.

used by defence-related industrial enterprises for

unknown purposes (AMAP, 2000) and tracing the fate

According to the Regional Veterinary Medicine

of these PCB-containing products has proved problem-

Administration (pers. comm.: letter no. 38/482 of

atic. In view of the fact that Murmansk Oblast is known

08.04.2003), the pesticide `Etacyde' was used in the

to have a high concentration of defence-related activi-

1960-1970s on reindeer farms in the Murmansk region

ties, particularly in previous decades, it might reason-

to treat the animals against subcutaneous reindeer gad-

ably be assumed that a considerable proportion of

flies. From the early-1980s until the present, the pesti-

these products were used here, and probably con-

cide `Ivomex' has been used. According to the infor-

tributed to PCB contamination of the area.

mation received, there has been no treatment used

against blood-sucking insects.

Dioxins and Furans

Data on emissions of dioxins and furans from industrial

A tentative (but not comprehensive) inventory of

enterprises are not included in the state statistical

stocks of obsolete pesticides in Murmansk Oblast, has

reporting system, and therefore there is no information

identified a number of stocks in the study area (Table

on their contribution to pollution of the survey area.

4.22). It should be noted that this information also

Some enterprises, such as the combined nickel smelter

lacks data on stocks of chlorinated pesticides, except

`Severonikel' are likely to be sources of dioxins, but

one enterprise in the city of Murmansk.

there is no information available to confirm this assump-

tion. Overall, there are a number of dioxin sources that

are likely to affect the survey area (Table 4.23).

Table 4.22. Stocks of obsolete pesticides in the Murmansk Oblast, kg.

(in bold letters the inventory area)

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

There is no statistical registration or control of PCB

release to the environment. Therefore, for the invento-

ry of possible PCB pollution sources, all enterprises in

the cities and villages mentioned above, plus the enter-

prises of the regional energy company `Kolenergo' JSC

were canvassed. According to data provided by these

enterprises, the total number of power transformers in

the survey area is 1590, including 1458 in operation

and 132 in reserve. However, most of them are filled

with the following mineral oils: T-1500, Tkp, Tk, T-750,

Table 4.23. Main sources of dioxin formation

GOST 982-56, GOST 10121-76, TP-22, and OMTI,

and emissions (Kluyev et al., 2001).

63

4.4. Local pollution sources in the vicinities of indigenous communities

Chapter 4

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

·

`Rick-market' Ltd (Kolsky Distrikt), a new installa-

Of the large group of PAH compounds, only emissions

tion with environmentally sound recovery of mer-

of benzo[a]pyrene are documented. No instrumental

cury wastes;

control measurements of benzo[a]pyrene emissions are

·

`Ecord' Ltd (Kirovsk), an outdated installation that

carried out, however. Emissions have therefore been

entered into operation in 1994. According to envi-

estimated for heat and power plants using fossil fuels;

ronmental protection authorities, this plant,

metallurgical plants (`Severonikel' JSC, `Olcon' JSC);

although utilizing a proportion of lamps from

and mining enterprises (`Apatit' JSC, `Sevredmet' JSC).

Murmansk Oblast, actually contributes itself to mer-

cury contamination of the environment. It should

In general, the two major PAH pollution sources are

be stressed that this enterprise is located within the

fossil fuel, including raw oil, combustion, and the

survey area.

incomplete incineration of organic materials such as

wood, coal and oil. Usually, the heavier the fuel source,

Re-cycling of other equipment and instruments con-

the higher the PAH content.

taining mercury, as well as of metallic mercury itself, is

not systematically organized. Also, the two plants men-

The main anthropogenic sources of PAH are:

tioned above only treat used lamps from industrial

production of acetylene from raw gas;

enterprises and not from the wider community.

pyrolysis of wood, producing charcoal, tar and

soot;

Another significant source of mercury contamination

pyrolysis of kerosene, producing benzene,

is the mobilisation of mercury impurities within differ-

toluene and other organic solvents;

ent industrial activities. According to expert estimates,

electrolytic aluminum production with graphite

the annual mobilization of mercury impurities within

electrodes;

the Russian Federation comprises 83% of the annual

coke production;

intentional use of this metal. However, the amount of

coal gasification;

mercury released to the air through mobilisation is six

production of synthetic alcohol;

times greater than that from intentional use (COWI,

oil-cracking.

2004).

Large amounts of PAH can also be formed as a result

Nickel and copper production are among the most

of:

important sources of mercury mobilisation. As one of

incineration of industrial and domestic wastes;

the largest producers of primary nickel in the Russian

forest fires;

Federation, the `Severonickel' combined smelter (with

energy production based on the incineration of

annual production of 103000 t of nickel and 132700 t of

fossil fuel;

copper in 2001) is located in Monchegorsk, it must be

motor vehicles.

considered as a significant source of mercury contami-

nation in the area. The average content of mercury in

Benzo[a]pyrene emission data for the inventory area

the sulphide copper-and-nickel ore that is used in this

(Table 4.24), clearly show that information on emis-

smelter is 1 mg/kg (Fedorchuk, 1983). However, this

sions from industrial enterprises, even based on esti-

level can vary depending on the origin of the ore, from

mates, is extremely scarce.

0.05-0.11 mg/kg in ore from the Monchegorsk deposit

to 2.78 mg/kg in ore from the Nittis-Kumuzhie (Kola

Mercury

peninsula) deposit. It should be noted that, in recent

Intentional use of mercury in industrial production

decades, the `Severonickel' combined smelter has also

within Murmansk Oblast has not been documented.

used ore from different deposits, including those on

However, mercury-containing devices, luminescent

the Taymir peninsula. Given this, the average content of

lamps in particular, are widely used and contribute to

1 mg/kg provided above may be considered as a fair

environmental contamination, due to the lack of envi-

estimate. Expert estimates carried out within the ACAP

ronmentally sound waste handling. Mercury-contain-

project `Assessment of Mercury Releases from the

ing wastes (mostly discarded luminescent lamps), are

Russian Federation' concluded that mercury emissions

the main contributors to wastes of the highest hazard

from the `Severonickel' combined smelter were 0.18-

class (31.7 t in 2001. There are two enterprises involved

0.22 t in 2001. In addition, a further 0.0750.111 t was

in the treatment of spent luminescent lamps:

accumulated in captured dust (COWI, 2004).

Table 4.24.

Trends in emissions

of benzo[a]pyrene to the

atmosphere in the Murmansk

Oblast inventory area.

64

Chapter 4

4.4. Local pollution sources in the vicinities of indigenous communities

Lead

Coal combustion is considered a major contributor to

lead emissions, along with the combustion of other fos-

sil fuels. (Figure 4.62). In the middle of the 1990s, con-

tributions from coal and gasoline combustion were

comparable. However, in the late-1990s, due to the

reduction in the use of leaded gasoline, coal became

the dominant source of lead emissions. Total emissions

Figure 4.62. Trends in lead emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels

from the combustion of fossil fuels in the area have

in the Lovozero area, kg.

decreased in recent years, mainly due to the reduction

in emissions from motor vehicles (Figure 4.63).

Figure 4.63.

Contribution of different

branches of economic

Mercury

activity to total lead

Mercury mobilization due to the use of fossil fuels is

emissions through the use

mostly determined by fuel combustion in industrial

of fossil fuels in the

Lovozero area, kg.

sectors and energy plants (heat and power plants,

HPP). Fuel consumption by municipal services and the

general population comprises only a minor part of

total emissions (Figure 4.64). It should be noted that

mercury emissions from this source have not changed

significantly during recent years.

The role played by fossil fuel combustion in total mer-

cury contamination arising from local sources, is sig-

nificantly less than that due to mercury mobilization

through nickel and copper production at the

`Severonickel' combined smelter (not more than 3%).

However, given that domestic use of organic fuel, par-

ticularly coal, often contributes to the contamination

of the indoor environment, its significance in terms of

Figure. 4.64. Contribution of different branches of the economy to total mercury

human intake may be much greater.

emissions through fossil fuel combustion in the Lovozero area, kg.

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

Estimates of PAH mobilization through the use of

organic fuel in the Lovozero area were made using

methods similar to those for heavy metals (Figure 4.65).

PAH releases have gradually decreased since the early-

1990s, possibly due to changes in the fuel types used.

However, after 1998, the amount of PAH released sta-

bilized, possibly due to the recovery of economy after

the 1997 crisis.

Figure 4.65. Mobilization of PAH compounds (benzo[a]pyrene, benzo[b]fluoran

thene, benzo[k]flouranthene, and indeno[1,2,3 c,d]pyrene) through the combustion

Dioxins

of organic fuel in the Lovozero area.

The trend in dioxin emissions with organic fuel com-

bustion in the Lovozero area is presented in Figure

4.66, which shows a decline during the early-1990s, but

4.4.2.3. PTS mobilization from combustion of fossil fuels

little change in emission levels since the mid-1990s.

Official statistical data exists on the consumption of

fossil fuels in Murmansk Oblast as a whole, but there

Industrial enterprises are the main source of dioxin

are no data on organic fuel consumption in the survey

pollution from organic fuel in the Lovozero area

area itself. According to statistics, about 23% of the

according to Figure 4.67. However, it should be noted

total population of the Murmansk Oblast live in the

Figure 4.66.

survey area, and in order to estimate emissions from

Dioxin emission trend

fossil fuel consumption it was therefore decided to

in the Lovozero area from

assume that use of fuel is proportional to the share of

organic fuel combustion.

the population. For calculation of dioxin and lead

emissions from gasoline combustion, it was assumed

that consumption of leaded gasoline in the survey area

comprised about 20% of total gasoline consumption

within the Oblast.

65