Ilulissat

The Arctic

Seqinersuup alakkaqqilerpai

qaqqavut kusanartorsuit

qamani neriuutit ikippai

maqaasiuartakkavut*

(The sun has begun to appear again

Our beautiful mountains

have ignited hopes within us

that we have missed all this time)

In mid-January every year, people in Greenland

gather to greet the returning light. In Ilulissat,

they sing this greeting, waiting for the sun to

peek above the horizon. Its first rays manage

only a brief glimmer, but the promise they

bring is strong, the hope of summer:

Seqinersuup qimaatilereerpaa

ukiorsuup kaperlassua

(The sun has put to flight

winter's long gloom)

Dark winters followed by long summer days

are one of the most profound features of the

Arctic, and are responsible for the ubiquitous

snow and ice. The spring and summer sun

brings enough energy to sustain life, but not

enough to melt all the frozen water or the

frozen ground. Ice and snow have therefore

shaped and are still shaping the northern

landscape.

The Arctic is not a uniform environment.

Different geological histories, warm and cold

ocean currents, and varying weather patterns

bring diversity to the scene. A circumpolar

voyager will meet everything from the perma-

MJAALAND

nent ice cover of the High Arctic to the boreal

forest of the subarctic, with the wide expanse

of tundra in between.

This chapter describes the land, the seas, and

the climate of the AMAP region, setting the

GREENLAND TOURISM/LARS

stage for the rest of the report.

*Greenlandic text: Samuel Knudsen, Kangersuatssaat

low climate more than solar radiation. Clima-

tically, the Arctic is often defined as the area

north of the 10°C July isotherm, i.e. north of

the line or region which has a mean July tem-

perature of 10°C.

The climate is highly influenced by regional

weather patterns and ocean currents. In the

Atlantic Ocean west of Norway, the warming

effect of the North Atlantic Current (an exten-

sion of the Gulf Stream) pushes this 10°C iso-

therm north of the Arctic Circle, so that only

NILSSON

the northernmost parts of Scandinavia are

ANNIKA

included in this definition. In North America

The Arctic Circle

and northeast Asia, the isotherm is pushed

marked in the terrain

next to the railroad in

What is the Arctic?

south by cold water and cold air moving down

from the Arctic Basin. Here the Arctic would

Sweden.

Arctos is Greek for bear, and the Arctic region

include northeastern Labrador, northern Que-

derives its name from the stellar constellation

bec, Hudson Bay, central Kamchatka, and the

of Ursa major, the Great Bear. A common geo-

Bering Sea. Greenland and most of Iceland

graphical definition of the Arctic is the area

also fall north of this isotherm.

north of the Arctic Circle (66°32'N), which

encircles the area of the midnight sun.

A treeline boundary

would move Arctic limits further south

July temperatures

A third definition of the Arctic region uses the

create a climatic definition

treeline as the boundary. Simply put, the tree-

From an environmental point of view, defining

line is the border between southern forests and

the Arctic solely on the basis of the Arctic

northern tundra. It is a transition zone where

Circle makes little sense. Vegetation types fol-

continuous forest gives way to tundra with

Boundaries of the Arctic

Arctic Circle

10°C July isotherm

Treeline

Marine

AMAP

Southern boundaries of

the High Arctic and

the subarctic delineated

on a basis of vegetation

High Arctic

80°N

subarctic

70°N

60°N

sporadic stands of trees and finally to treeless

· In the Bering Sea area, the southern bound-

7

tundra. In North America, the tundra-forest

ary is the Aleutian chain.

The Arctic

boundary is a narrow band, but in Eurasia it is

· Hudson Bay and the White Sea are consid-

up to 300 kilometers wide. The treeline corre-

ered part of the Arctic for the purposes of

sponds with a climate zone where the cold

the assessment.

Arctic air meets warmer airmasses from far-

· In the terrestrial environment, the southern

ther south.

boundary in each country is determined by

In some places, the treeline roughly coin-

that country, but lies between the Arctic

cides with the 10°C July isotherm, but across

Circle and 60°N.

much of mainland Eurasia and North America

The map on the opposite page shows the

the treeline is 100 to 200 kilometers south of

area covered in this report.

the isotherm. By the treeline definition, the

Eight countries have land within the area

Arctic also includes western Alaska and the

of AMAP's responsibility: Canada, Denmark

western Aleutians.

(Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Finland,

The subarctic lies between the treeline to the

Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the

north and the region to the south where the

United States (Alaska).

forest becomes dense enough to have a closed

canopy. The subarctic is also called the taiga or

forest tundra. Permafrost (permanently frozen

ground) is only present in patches, and in sum-

The land

mer the unfrozen layer is generally thick. The

presence of discontinuous permafrost is some-

About 13.4 million square kilometers, 40 per-

times used to define the subarctic, in contrast

cent, of the AMAP area is covered by land.

to the Arctic where permafrost is continuous.

The map below shows the major physical-geo-

graphical regions. Old crystalline shields under-

Meeting of cold and warm water forms

lie most of eastern Canada, Greenland, and

the marine boundary

Fennoscandia. Younger sedimentary rock,

eroded into plains, covers large parts of Russia

The marine boundary of the Arctic is formed

and the Mackenzie River valley in Canada. In

when the water of the Arctic Ocean, cool and

the Ural Mountains, in the northeastern corner

dilute from melting ice, meets warmer, saltier

of Russia, in Alaska, and in the Yukon Territo-

water from the southern oceans. In the Cana-

ries of Canada the sedimentary rock has folded

dian Arctic Archipelago, this belt is at approxi-

into mountain ranges. Similar folded sedimen-

Major physical-geo-

graphical regions of the

mately 63°N and swings north between Baffin

tary rock forms the mountain ranges of the

Arctic. Colors indicate

Island and the coast of west Greenland. Off

northern Canadian Arctic islands. Iceland and

similar landscape fea-

the east coast of Greenland, the marine bound-

the Aleutian islands are of volcanic origin.

tures.

ary lies at approximately 65°N. In the Euro-

pean Arctic, the marine boundary is much far-

ther north, pushed to about 80°N to the west

of Svalbard by the warming effect of the North

Atlantic Current. At the other entrance into

the Arctic, warm Pacific water flows through

the Bering Strait to meet Arctic Ocean water at

East Siberian

North American

about 72°N, forming a boundary that stretches

Highlands

Cordillera

from Wrangel Island in the west to Amundsen

Interior

Gulf in the east.

Plain

Central

AMAP's boundaries

Siberian

Arctic

Plateau

Islands

Because of the difficulty of defining the Arctic

in a way that is relevant for all areas of sci-

Hudson

ence, AMAP does not define the Arctic but

Lowlands

West

Canadian Shield

Siberian

gives a guideline about the core area to be cov-

Ural

Lowland

Mountains

ered by the AMAP assessment. The boundary

East European

should lie between 60°N and the Arctic Circle,

Plain

with the following modifications:

Baltic

Shield

· In the North Atlantic, the southern bound-

North

Atlantic

ary follows 62°N, and includes the Faroe

Islands

Islands, as described in `The Joint Assess-

ment and Monitoring Programme' of the

Convention for the Protection of the Marine

Environment of the North-East Atlantic (the

OSPAR Convention). To the west, the La-

brador and Greenland Seas are included in

the AMAP area.

BRY

KNUT

Glacier Bay, Alaska.

Ice has shaped the landscape

hard crystalline granite bedrock, the glaciers

left the land dotted with depressions that filled

On a shorter time scale, ice has put its signa-

with water and became lakes. Glaciers that

ture on most of the terrestrial landscape. Some

eroded the bedrock below sea level at the coast

of the land is covered by glaciers, which are

created deep, winding fjords. In other areas,

large masses of snow and ice that flow under

the glaciers piled extensive moraines and sedi-

their own weight. Glaciers form where the

mentary deposits on top of the bedrock.

mean winter snowfall exceeds mean summer

Some of the land is still rebounding after

melting. Melting, refreezing, and pressure

being pressed down by the weight of the ice

gradually transform the snow to ice.

sheets during the latest glaciation. Along the

Many areas have been shaped by repeated

coasts, the land is still emerging from the sea.

glaciations. In the North American and west-

Around Hudson Bay, for example, the land

ern Eurasian Arctic, ice sheets have scoured

rises at a rate of one meter per century.

the landscape like giant bulldozers, tearing

away topsoil and broken rock. In areas with

Permafrost creates patterned ground and

Discontinuous permafrost

governs water movement

Continuous permafrost

Ice cap /glacier

Much of the ground is frozen by permafrost,

and only a thin top layer, called the active layer,

thaws each summer. Permafrost is defined as

ground that remains frozen for at least two

summers in a row. The frozen layer can reach

depths of 1500 meters in the coldest areas of

the Arctic. The active layer ranges between a

few centimeters in the northernmost wet mead-

ows to a few meters in warmer, drier areas

with coarse-grained soils. Perennially frozen

ground occurs throughout the Arctic and ex-

tends into the forested regions to the south.

Along the northern coasts, frozen grounds

meet the sea, and the permafrost extends

under some shelf seas.

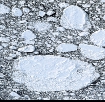

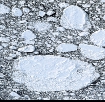

The constant freezing and thawing in per-

mafrost areas makes the ground move. In the

process, debris is sorted and rocks are forced

to the surface. In some areas this sorting has

created extensive polygonal patterns; see fig-

ures on the opposite page. Another physical

feature is the pingo, a mound of earth thrust

up by a core of ice. Pingos can be as high as 40

meters. Occasionally, changes in local climate

or physical disturbance of the ground can

Sphagnum peat

Sedge-moss peat

Permafrost table

Mineral soil

Ice

MCLEOD

Low-center polygons

5 m

KATHERINE

Amorphous peat

Organic-mineral mixture

Sphagnum peat

Sedge-moss peat

Mineral soil

Permafrost table

Ice

MCLEOD

High-center polygons

KATHERINE

cause the permafrost to melt. In some cases,

Cross-sections of low-

and high-centered poly-

this causes the ground to sink, and the depres-

gons found in Arctic

sion fills up with water, creating so-called ther-

wetlands. The low-cen-

mokarst lakes, which are unique to the Arctic.

tered polygons gradu-

Permafrost governs the fate of water in the

ally evolve into high-

Arctic landscape. For example, groundwater

centered polygons with

the accumulation of

formation is much slower in frozen ground

biomass.

than in unfrozen ground. The groundwater

can be on top of, in cracks within, or under-

neath the permafrost layer.

WIDSTRAND

In spring, permafrost contributes to flood-

Tundra, Kolyma,

ing. Eighty to ninety percent of the freshwater

Russia.

STAFFAN

input to the land occurs during the two to three

weeks of snowmelt in spring. Instead of seeping

into the ground, the meltwater flows over the

frozen surface and into streams, rivers, lakes,

and various wetlands, which cover vast areas

on the flat plains.

The lack of oxygen in the waterlogged soil

of wetlands delays the decomposition of plant

matter and results in a build-up of organic ma-

terials, such as peat and humic substances. In

drier areas where the water can escape, such as

steep slopes and high narrow ridges, increased

WIDSTRAND

Driftwood and pingo,

bacterial activity in the soil leads to a lower

Tuktuyaktuk, Yukon,

content of organic matter. These areas often

STAFFAN

Alaska

Well drained site

Impervious ground at surface

forces water to percolate through

the unfrozen part (talik) in permafrost

Substrate

Clay and silt

Poorly drained site

Gravel

Small lake

Permafrost

Active layer

Depth of

summer thawing

(bottom of active layer)

Groundwater

River

percolating throughout

the year

percolating only during

the warm season

Groundwater in perma-

frost.

The seas

The marine areas within AMAP's boundaries

cover approximately 20 million square kilome-

ters. These include the Arctic Ocean, the adja-

cent shelf seas (Beaufort, Chukchi, East Siberi-

an, Laptev, Kara, and Barents Seas), the White

Sea, the Nordic Seas (Greenland, Norwegian,

and Iceland Seas), the Labrador Sea, Baffin Bay,

Hudson Bay, the Canadian Arctic Archipelago,

and the Bering Sea. The narrow Bering Strait

connects the Arctic Ocean and the Bering Sea

(and the Pacific Ocean), while the main con-

nection between the Arctic Ocean and the

northeast Atlantic Ocean (Nordic Seas) is via

the deep Fram Strait and the Barents Sea. There

are two major basins in the Arctic Ocean, the

Canadian Basin and the Eurasian Basin, sepa-

rated by the transpolar Lomonosov Ridge.

The Arctic Ocean has a vast continental

shelf, extending from northern Scandinavia

eastward to Alaska. All the Eurasian marginal

seas are located over this shelf, which has a

width of up to 900 kilometers off the coast of

Siberia. Off North America, the shelf extends

only 50 to 100 kilometers from the coast.

WIDSTRAND

Most of the water in the Arctic Ocean comes

from the Atlantic Ocean via Fram Strait and

STAFFAN

the Barents Sea, with some additional inflow

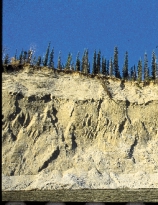

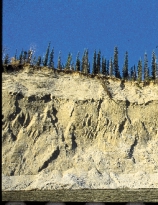

Erosion, Kobuk River,

have a characteristic soil profile caused by the

from the Bering Strait. Rivers account for about

Alaska.

redistribution of soil particles and chemicals.

two percent of the input, a high proportion

Arctic rivers also owe much of their charac-

compared with other oceans. The main outflow

ter to the permafrost. Because the ground has

from the Arctic Ocean is via the East Green-

such a limited ability to store water, the spring

land Current, with a minor portion flowing

flood can be violent, undercutting the river

out via straits in the Canadian Archipelago.

bank and causing extensive erosion along its

The water flow is further described in the figure

path. Ice jams add to the uneven flow and ero-

on page 31. A prominent feature in the surface

sion. The rivers thus carry huge amounts of

water is the oceanic polar front, which sepa-

sediments that are deposited along their course

rates the cold, less saline surface water of the

and in wide deltas.

Arctic Ocean from saltier, warmer water origi-

nating in the oceans farther south. The posi-

tion of the front is relatively stable in most

Natural resources are abundant

areas, moving little from year to year.

The circumpolar region has numerous large

Surface water temperatures vary both sea-

deposits of fossil fuels and minerals. Examples

sonally and geographically. In the Arctic Ocean,

include nickel in the vicinity of Norilsk in Rus-

the surface water temperature is close to freez-

sia, the recently discovered diamond deposits

ing point year-round because of the ice. In the

in the Northwest Territories in Canada, coal in

shelf areas, the sun can warm the water from

Svalbard, and oil and gas fields at Prudhoe Bay

freezing point in winter to 4-5°C during sum-

in Alaska and in many other areas that are de-

mer. In areas influenced by Atlantic and Pacific

scribed in the chapter Petroleum Hydrocarbons.

water, there may be greater seasonal variabil-

The AMAP region also contains many re-

ity, and the temperature remains higher than

newable resources. Forests supply fuel for

0°C throughout the year.

energy and material for pulp and paper pro-

Salinity varies with depth and with the

duction. Both marine and freshwater ecosys-

water's source. Arctic surface water is less salty

tems are important for commercial fishing.

than the deep ocean water and than the surface

Powerful rivers provide hydroelectric power,

waters of other oceans because of meltwater

while geothermal energy is used for heating in

from ice as well as large inputs of freshwater

some areas.

from north-flowing rivers. The highest salinity

11

The Arctic

KASSENS

HEIDI

The central Arctic Ocean.

is in water of Atlantic or Pacific origin. The

salinities. This is further discussed on page 31.

fresher water floats on top of more saline water,

The halocline that separates the fresher from

and the water mass is best described as having

the saltier water creates a lid that keeps deeper,

distinct layers with different temperatures and

warm water from reaching the surface.

Pacific

Ocean

Bering

Sea

Yukon River

210 km3 per year

Bering

Strait

Chukchi

Kolyma

Sea

132 km3 per year

Mackenzie River

333 km3 per year

East Siberian

Sea

Beaufort

Sea

Arctic Ocean

Laptev

Lena, 525 km3 per year

Depth, m

Sea

0

Canadian Basin

100

Nelson River

Canadian

500

75 km3 per year

Arctic

Archipelago

1000

Eurasian

Lomonosov Ridge

Basin

Yenisey, 630 km3 per year

2000

Hudson

Kara

3000

Bay

Sea

Ob, 404 km3 per year

5000

Baffin

Bay

Fram

Freshwater discharge

Strait

Barents

Pechora

Catchment area

Sea

140 km3 per year

North Greenland

Labrador

Sea

Sea

Northern Dvina

106 km3 per year

Iceland

Greenland

Sea

Sea

Norwegian

Sea

Atlantic

Ocean

Bathymetry of the Arctic

Ocean and adjacent seas

and freshwater input

from major rivers.

Hudson Bay in Arctic Canada is considered

part of the AMAP area even though it extends

as far south as 51°N. The bay is ice-covered in

the winter, and gets much of its water from

rivers draining central and northeast North

America. A similar semi-enclosed body of wa-

ter in the Eurasian Arctic, also heavily influ-

enced by freshwater runoff, is the White Sea.

Sea ice dominates the Arctic Ocean

Ice is the most striking feature in the Arctic

Ocean. The perennial pack ice covers about 8

million square kilometers. The total area cov-

Shallow, warm

ered by sea ice changes with season, reaching

its peak in March to May, at about 15 million

square kilometers; see figure below left.

The ice is in constant motion, following the

Deep, cold

major currents and growing in thickness as it

moves along. The trip from one end of the

The polar front influences global ocean currents

Arctic Basin to the other can take up to six

The Arctic plays a fundamental role in the circulation of water in the oceans of the

years, allowing the ice to grow as thick as

world. When warm, salty North Atlantic water reaches the cold Arctic around Green-

three meters or more; see the map on page 32.

land and Iceland and in the Labrador Sea, it becomes denser as it cools, and therefore

Forces from winds, upwelling water, and

sinks to deeper layers of the ocean. This process of forming deep water is slow, but takes

water currents create strains and stresses on

place over a huge area. Every winter, several million cubic kilometers of water sink to

deeper layers, which move water slowly south along the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

the moving ice, which lead to patches of open

water even in the depths of winter. In some

areas, these leads and polynyas are formed

every year and serve as important gathering

Many coasts feature semi-enclosed

grounds for marine wildlife and as hunting

bodies of water

grounds for Inuit. They also represent areas of

Semi-enclosed water bodies in the Arctic

high energy exchange between the ocean and

Basin include fjords, bays, straits, and chan-

the atmosphere. During summer, about 10 per-

nels between islands. Many of these estuarine

cent of the pack ice area is actually open water.

environments are important links between the

In other areas, the ice is pushed into huge

terrestrial environment and the ocean because

hummocks and pressure ridges. The height of

they act as sediment traps.

hummocks is typically 4 to 5 meters, but they

Each of the semi-enclosed bodies of water

sometimes reach heights of 12 to 15 meters.

is unique, and its environment is governed by

An underwater ice ridge can extend 30 to 40

ice cover and tides. In Frobisher Bay, Baffin

meters below the surface.

Island, for example, the tides are extreme.

Shelf seas mainly have first-year ice, which

In Lancaster Sound, Baffin Bay, an area of

builds from the coast and the ice edge during

open water within sea ice, called the North

winter. Offshore winds often separate the pack

Water Polynya, forms every year. Fjords in

ice from the landfast ice.

some regions, such as Norway, are ice-free

year-round, due to the warming effect of the

North Atlantic Current.

Maximum and minimum

sea-ice extent.

September

ice edge

March ice edge

WIDSTRAND

STAFFAN

Pancake ice.

13

The Arctic

KASSENS

HEIDI

Nilas ice, Laptev Sea.

The icescape from near and far

About a century ago, the Norwegian Arctic explorer Fridtjof Nansen traveled over

the drifting ice pack in his quest for the North Pole. Some days the ice was smooth

enough to allow the sleds an easy passage, but oftentimes open water came in the

way or huge hummocks turned his travel into arduous work. His description from

early August 1895 gives a sense of the Arctic icescape:

`It was as if a giant had thrown the worst iceblocks helter-skelter, strewn deep,

wet snow between them and water underneath, so that we sank all the way up to

our thighs . . . It was like struggling over mountains and valleys, up and down over

block after block, and ridge after ridge with deep crevices between, not an even sur-

face large enough to put a tent on.'

Fridtjof Nansen: Fram over Polarhavet, 1897.

Today's Arctic travelers can get a bird eye's view of this icescape:

`Flying over the ice is an easy way to appreciate its tectonic activity on a larger

scale, to better understand it as the never-quite-settled surface of the Arctic Ocean.

From above, the finger-rafting of huge, transparent sheets of nilas seems like a deli-

cate and regular joinery of panes of glass . . . Dark ice cakes below prove to be ones

covered with epontic algae and flipped over by animals, or places where walrus

have hauled out, rested and defecated. Long streaks on gray-white ice cutting across

a broad, snow-covered expanse show where leads have recently frozen over. A low

pressure ridge may lead to a dark hole and a patch of reddish snow, a polar bear

kill. Streamers of grease ice in patches of open water line up with the wind. In win-

ter the leads steam with frost smoke where the (relatively) warm water meets the

frigid air.'

F R I D T J O F N A N S E N A N D H J A L M A R J O H A N S E N , S U M M E R 1 8 9 6

Barry Lopez: Arctic Dreams, 1986

KASSENS

Black nilas ice,

HEIDI

Laptev Sea

14

Climate

example, the mid-latitude jet streams and the

low- and high-pressure systems embedded in

The Arctic

Weather in the Arctic can be more extreme

them are results of the on-going heat exchange.

than in most other areas of the world, with

The stronger the temperature differences, the

low temperatures and strong winds. The

stronger the jet streams. Therefore, the strongest

region includes some of the coldest places on

storms occur in winter. The heat exchange be-

Earth, but temperatures and weather patterns

tween the Arctic and areas farther south is also

vary greatly among different regions of the

important for understanding contaminant trans-

AMAP area.

port and global climate change as described in

later chapters.

A cold reservoir in a global heat machine

The High Arctic is cold and dry

One basic feature of the Arctic climate is

that the sun never reaches high in the sky, even

The temperature over the Arctic Ocean is mod-

in summer, which limits the total amount of

erated by heat released through the ice from

incoming solar energy. Moreover, in snow-

the underlying water, but winter air tempera-

covered areas as much as 90 percent of the

tures over the permanent ice pack still fall to

incoming solar energy is reflected back to

30°C . The cold air cannot hold much mois-

space by the snow and ice. Furthermore, the

ture. Together with the lack of open water, this

area loses heat back to space as infrared radia-

creates very dry conditions in the High Arctic,

tion. This is compensated by heat exchange in

making a cold desert environment. It might

the atmosphere and ocean currents that carry

snow often, but little falls each time, so the

relatively warm air and water masses north-

total accumulation of snow is relatively low in

ward and cold air and water southward. The

winter. Precipitation on northern Greenland,

Arctic region also imports moisture from sur-

for example, is hardly more than 100 millime-

rounding areas.

ters per year. Powerful high-pressure systems

Seeing the polar area as a refrigerator in the

in the Arctic often create clear, cold days in

equator-to-pole transport of energy is impor-

late winter and spring.

tant in understanding weather patterns. For

Summers in these far-north areas are

usually gray and foggy as mild, humid air

1000

moves in over the cold water. Cloud cover in

Aleutian low

summer ranges from 70 to 90 percent. The

1004

1008

amount of precipitation is still low, however,

1012

and temperatures remain between 10 and

1016

+10°C, with temperatures most commonly

Atmospheric

pressure,

High

around freezing.

January means,

1024

1020

millibar

1024

1020

High

Elevation

1028

1032

1016

Coastal and continental

2000 m

climates can be very different

1000 m

1012

Farther south, average temperatures and pre-

1008

cipitation are governed by the major move-

1004

1000

1020

ment of air masses and the proximity to open

Icelandic low

1004

water. For example, winter circulation patterns

1008

1012

bring cold air from the Arctic Ocean south-

1016

ward over North America. Over the continen-

1016

tal parts of the Arctic, stable, cold high-pres-

sure systems prevail during typical winters.

These are particularly well developed over Sibe-

1024

ria and northwestern Canada.

1020

1016

The winter high-pressure systems are accom-

1012

panied by weak winds and thermal inversions,

allowing cold air to gather in the lower one-to-

two kilometers of the atmosphere. The lowest

Low

temperatures are usually recorded in typical

1004

continental climates, such as the inland areas

Atmospheric

1008

pressure,

Canadian low

of Alaska, Siberia, eastern Arctic Canada, and

July means,

1008

Greenland. Minimum winter temperatures

millibar

across inland areas in the Arctic range from

1012

20 to 60°C.

There are large temperature differences be-

1012

1016

tween winter and summer over the continents.

1020

In some parts of Siberia and in the interior of

Patterns of high- and

1024

low-pressure systems in

Alaska, temperatures can range from less than

High

winter and summer.

50°C in winter to above +30°C in summer.

15

The Arctic

Surface air temperature, °C

9.5

7

2

3

8

13

18

23

28

33

38

43

January

July

48

Coastal areas often have a maritime climate.

warm seasons, the Icelandic and Aleutian lows

Surface air tempera-

Around the Norwegian and Barents Seas, for

weaken considerably.

tures in winter and

example, winter temperatures are on average

Inland areas of the Low Arctic are generally

summer.

only just below freezing because of the warm

dry, with decreasing precipitation from south

North Atlantic Current. Even as far north as

to north. East Siberia, Northern Canada, and

Svalbard, mean winter temperatures are only

Greenland receive less than 140 millimeters

about 12°C, about 20°C higher than those at

per year.

the same latitude in the Canadian Arctic Archi-

Winds have a great impact on the polar

pelago. As in most maritime climates, the tem-

environment because they aggravate the chill-

perature difference between summer and win-

ing effect of low temperatures. The open Arc-

ter around the Norwegian and Barents Seas is

tic landscape does not slow the winds, which

not as great as in inland areas. Other areas

are also important in mobilizing snow, causing

with typical maritime climates are Iceland and

scouring in exposed areas and deposition in

the south coast of Alaska.

sheltered locations. In the marine environ-

ment, wind affects sea surface stability and

increases mixing in the water column. It also

Semi-permanent low-pressure systems

produces ocean currents and influences ice

govern winds and precipitation

drift and the formation of polynyas.

Wind patterns and precipitation in the Low

In winter, unstable conditions in the cold air

Arctic are governed by the low-pressure sys-

over the open, relatively warm oceans north of

tems that form over the North Atlantic and the

the polar front often trigger the formation of

Bering Sea, bringing warm, moist air north-

polar lows. They are much smaller than the

ward. These weather systems, the Icelandic

more permanent lows, but they bring stormy

and Aleutian lows, gather moisture over open

weather and high winds farther south.

water and dump it as precipitation when the

Temperature inversions over ice sheets on

air is forced to rise. The windward sides of

land can create local, extremely strong winds

mountainous areas often have daily rain or

in the winter, as cold air surges downhill, usu-

snow. Southern Iceland and parts of the Nor-

ally from the ice toward the sea. Such kata-

Svalbard.

wegian coast can thus get extreme yearly pre-

batic winds are frequent and persistent around

cipitation, exceeding 3000 millimeters. In the

Greenland.

Norilsk, Russia.

BRY

BRY

KNUT

KNUT

16

The Arctic

WIDSTRAND

Baffin Island, Canada.

STAFFAN

A circumpolar voyage

Greenland, which is geologically a part of

North America, is a mountainous island. Most

As a result of the combined effects of geology,

of it is covered by a permanent ice cap, which

ice, and climate, the lands covered in the

reaches elevations of 3000 meters. Many of

AMAP assessment are very diverse. Circling

the glaciers extend all the way to the sea, and

twice around the Arctic, first among the

western Greenland produces icebergs at a rate

islands and then through the continents, gives

of 300 cubic kilometers per year. The Jakobs-

the traveler a sample of features that are typi-

havn Isbrae alone creates 25 cubic kilometers

cal of the different regions..

of icebergs per year as the ice tongue glides

Icy island outposts

The archipelagos of northern Canada, Green-

land, and the islands north of Scandinavia and

Russia form the terrestrial outposts farthest to

the north.

Canada's northernmost area is the world's

largest archipelago, with 20 large and many

smaller islands, some of which are covered by

ROSING

Kangerlusuaq,

extensive glaciers. The Canadian Arctic Archi-

East Greenland.

pelago starts with flat to rolling plains in the

MINEK

west (Banks, Melville, Victoria, Bathurst, and

Narsaq, southern

Prince of Wales Islands), building up to rug-

West Greenland.

ged, ice-capped mountains in the northeast

(Baffin, Devon, Axel Heiberg, and Ellesmere

Islands) toward Greenland. The northernmost

land is Ellesmere Island, where the Agassiz ice

cap covers much of the central part of the is-

Ellesmere Island,

land. The fjords and straits between the islands

Canada.

are often blocked by pack ice.

ROSING

MINEK

forward at an average rate of 20 meters a day.

In areas where the ice does not reach the sea,

meltwater flows into abundant lakes and river

systems.

Along the coasts, conditions are governed

by water temperature. The south-flowing East

Greenland Current brings cold water and ice

down from the Arctic Ocean. As much as six

million tonnes of ice travels down the coast

per year, almost blocking it from open water.

Farther south, the warm Irminger Current has

created a more favorable climate. The current

mixes with colder water, but still manages to

WIDSTRAND

bring relative warmth to the coastal areas

around Baffin Bay and southwest Greenland.

STAFFAN

The coastal waters from Qaqortoq to Sisimiut

17

The Arctic

OSING

R

MINEK

Isua, West Greenland.

on the west side of Greenland can be open

year-round, and winter sea ice does not become

the norm until Disko Bay and farther north.

Most of Greenland that is not covered by

glaciers is barren rock with only small patches

of low shrubs or grass. The main tracts of ice-

free land in Greenland are in the southwest,

the north (Peary Land), and the northeast.

The southwestern coast features some grazing

land for sheep, and vegetation that includes

WIDSTRAND

small trees.

The Svalbard and Franz Josef archipelagos,

Svalbard.

STAFFAN

the northern island of Novaya Zemlya, and

Severnaya Zemlya are extensively ice-clad,

mountainous islands, with glaciers calving ice-

bergs into the sea. Most of the ice-free land is

bare and rocky, since cold and lack of water

have not allowed much soil to form. The

southern Novaya Zemlya island is mostly an

ice-free coastal plain with continuous per-

mafrost. All of the Eurasian island outposts

are mountains rising from the wide continental

shelf. Novaya Zemlya is an extension of the

Ural Mountains. The highly productive sea

around the islands supports huge populations

of sea birds.

North Atlantic islands:

weather ruled by the sea

Iceland was created by volcanic activity along

the mid-Atlantic ridge some 20 million years

ago. New volcanic rock is constantly forming,

and volcanoes erupt regularly. About one tenth

HUNTINGTON

of Iceland is covered by lava deposited since

HENRY

Heimaey, Iceland

the last ice age. More than half of the surface

does not have any vegetation. About one tenth

of the land is covered by glaciers. The climate

on Iceland is warmed by the Irminger Current.

The extent of sea ice along the coast varies but

does not normally block shipping.

Another island on the mid-Atlantic ridge is

Jan Mayen, with its 2300-meter-high volcanic

mountain Beerenberg. It erupted as recently as

1970.

The North Atlantic part of the AMAP area

also includes the Faroe Islands, situated 300

kilometers north of Scotland and approximately

KUBUS

The Faroe Islands.

half-way between Iceland and Norway. This

18

archipelago has a landscape of low, bare

The Arctic

mountains, with plenty of grazing land for

sheep. The climate is oceanic: humid, change-

able, and windy. The ocean temperatures are

well above freezing.

Fennoscandia and Kola:

subarctic climate, lakes and forests

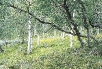

NILSSON

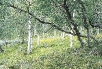

Fennoscandia, which includes Finland, Nor-

Sarek National Park,

Sweden.

ANNIKA

way, and Sweden, rests on old bedrock that

has been worn down to low hills and coastal

flats. The Norwegian coast features deep

fjords. Along the border between Sweden and

Norway, younger mountains form peaks as

high as 2000 meters, while the landscape gen-

erally flattens toward the north and east. The

area features an abundance of lakes.

The climate in this region is greatly influ-

enced by the warm North Atlantic Current.

The coasts have a long ice-free period and,

except on high mountains, the snow melts in

summer. Glaciers build in areas with high pre-

cipitation, where summers are too short to

OKSANEN

melt the snow in spite of fairly warm tempera-

Saariselkä, Finnish

Lapland.

ERKKI

tures. Farther inland, on the Norwegian Finn-

marksvidda and in Swedish and Finnish Lap-

land, the climate is continental, with warmer

summers than along the coast, but consider-

ably colder winters.

The vegetation represents a transition be-

tween the Arctic and the boreal forest with

many subarctic species. The boreal forest

reaches its northernmost point at Finnmarks-

vidda in northern Norway, a little south of

70°N. There are only patches of permanently

frozen ground.

The Russian Arctic: vast expanses

of tundra, wetlands and mountains

The Arctic area of the Russian plains (west of

the Ural Mountains) has been shaped by re-

peated build-up and retreat of glaciers that

have left a flatland rich in sediments. The per-

mafrost has created a tundra landscape along

the coast and some forest-tundra closer to the

Arctic Circle. Summers are cool, wet, and

short, while the winters are long, fairly mild,

and snowy.

WIDSTRAND

Going east toward the Ural mountains, the

Kolyma River delta,

climate becomes more severe with abundant

Russia.

STAFFAN

snow in the winter. Summers are cool. Most of

the northern Ural landscape is tundra, with

small glaciers in the mountains. Immediately

east of the Urals, the landscape is again flat,

but moving farther eastwards in Siberia, moun-

tains reappear.

Much of Arctic Siberia was never glaciated,

so pre-glacial soils were never disturbed and

thus provide a cover over the bedrock that sus-

tains forests. Siberia has one of the most severe

HUNTINGTON

climates in the Arctic, with extremely cold win-

Koyuk River, Russia.

HENRY

ters. Most years, even large rivers freeze to the

bottom for several months. Permafrost pre-

19

vails, with vast wetland areas and numerous

The Arctic

shallow lakes. The landscape is transected by

several large north-flowing rivers. Many of

these create deltas where they meet the ocean.

The coast is ice-bound for most of the year.

The northeastern corner of Russia has a

mountainous landscape. In a zone of active

low-pressure systems, its climate is more tem-

perate than farther west. In the Chukotka

mountains, the peaks reach elevations up to

1500 meters.

Alaska: rugged mountains, coastal plains

and volcanic islands

HUNTINGTON

Alaska's landscape covers a wide range of ter-

rains and climates. Rugged mountain ranges

HENRY

Chukotka, Russia.

stretch across the state in the north and south,

reaching 6194 meters at Mt. McKinley. There

are several active volcanoes in the Alaska

Range, and extensive glaciers in the south-cen-

tral and southeastern mountains. Wide coastal

tundra plains extend along the northern coast

and the southwest. The interior, drained by the

Yukon river, is forested and has a continental

climate, with extreme temperature variation

between summer and winter.

WIDSTRAND

From the west coast, the Aleutian chain

STAFFAN

Kobuk Valley, Alaska.

stretches westward across the Pacific. The cli-

mate on the Aleutian Islands is milder than in

the interior of Alaska, but strong winds are

common and can create severe weather

throughout the year.

Permafrost is extensive across the northern

third of Alaska, and is discontinuous for much

of the rest of the state. Along the northern

coast (the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas), sea ice

is common even in summer.

HUNTINGTON

Canada: from forests

HENRY

Brooks Range, Alaska.

to a frozen archipelago

At the westernmost boundary of Canada's

mainland Arctic is the Yukon Plateau, consist-

ing of rolling uplands with valleys and isolated

mountains. The climate in this region is sub-

arctic and supports forests.

Southwest of this plateau are the Coast

Mountains with extensive glaciers. To the

northeast of the Yukon Plateau are the Mac-

WIDSTRAND

kenzie Mountains. These mountain ranges give

way to the interior lowlands covered by exten-

STAFFAN

Ivavik, Yukon, Canada.

sive wetlands and transected by the Mackenzie

River. The Arctic climate becomes more pro-

nounced because of the cold air moving down

from the Arctic Ocean. Most of the ground is

permanently frozen.

The large Great Bear and Great Slave Lakes

extend from the interior lowland eastward into

the Canadian Shield. The shield continues to

the east coast and contains numerous lakes

and the vast expanse of Hudson Bay.

WIDSTRAND

Toward the north is the Canadian Arctic

Archipelago.

STAFFAN

Hudson Bay, Canada.