41

Chapter 5

Effects on Terrestrial Ecosystems

John Derome, Sirkku Manninen, Julian Aherne, Paavo Hellstedt, Jean-Paul Hettelingh, Kevin Hicks, Satu Huttunen,

Juha Kämäri, Galina Kashulina, Mikhail Kozlov, Annamari Markkola, Maximilian Posch, Anna-Liisa Ruotsalainen,

Reijo Salminen, and Elena Zvereva

The first AMAP assessment of acidification (AMAP, 1998)

addressed the processes involved in the acidification of

arctic soils, and the direct effects of sulfur dioxide (SO2)

and nitrogen oxides (NOX), as well as acidifying deposi-

tion, on the biotic components of terrestrial ecosystems.

At that time, however, there was little empirical evidence

to suggest that soil acidification was anything more than

a local problem in very limited parts of, for example, the

Kola Peninsula. The serious damage to flora and fauna

reported in the area was mainly attributed to the direct

toxic effects of SO2, combined with the accumulation of

toxic heavy metals in the arctic environment. It is extremely

difficult to distinguish between the direct effects of SO2, the

indirect effects of the deposition of acidifying compounds

(SO2 and sulfate (SO4)), and the direct toxic effects of heavy

metals on terrestrial ecosystems in the areas around the

smelters. In the Arctic, the cumulative effects of acidifying

emissions and the deposition of toxic heavy metals can

AMAP boundary

be disastrous for ecosystems which are already subject to

extreme climatic conditions. In this, the latest acidification

assessment, a large amount of new empirical data are pre-

sented and discussed.

Most

Least

No

sensitive

sensitive

data

5.1. Effects on soils

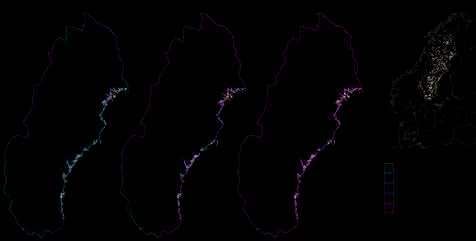

Figure 5.1. Sensitivity of arctic ecosystems to acid deposition (Kuylen-

stierna et al., 2001).

Kuylenstierna et al. (2001) have mapped the relative sen-

sitivity of terrestrial ecosystems to acidic deposition at the

global scale. An overview of the sensitivity of arctic ecosys-

tems is provided in a circumpolar map extracted from the

via long-range transport from industrial sources in China,

global sensitivity map. The sensitivity classes are based on

India, and other parts of the Far-East, reliable deposition

base saturation and cation exchange capacity data applied

data and information about the soil acidification status of

to FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) soil types.

the region are extremely difficult to obtain. Other parts of

The soils most sensitive to acidic deposition have a low

the Arctic receive acidifying compounds via long-range

base saturation (<40%) and a low cation exchange capacity

transport from North America, Europe and the Far-East

(<10 meq/100 g); the implication is that these soils have

but, according to deposition measurements made in the

low rates of long-term mineral weathering and a limited

Arctic, the levels are not likely to cause widespread soil

base cation content and may therefore be subject to rapid

acidification in background areas in the near future.

changes in base saturation and pH. The most sensitive ar-

eas occur in Fennoscandia, in parts of Russia, and in parts

of Canada and Alaska. Much of the Canadian Arctic seems

5.1.1. Acidity status of soils

not to be sensitive to acidic deposition (Figure 5.1).

on the Kola Peninsula

AMAP has identified three regions in the Arctic that

may be susceptible to acidification caused by the deposi-

The results of two regional studies the Kola Ecogeo-

tion of acidifying compounds (sulfur and nitrogen): the

chemistry Project (www.ngu.no/Kola) and the Barents

Kola Peninsula in northwestern Russia, the Taymir Penin-

Ecogeochemistry Project (www.gsf.fi/Barents) have

sula in northern Russia, and the Chukotka region in east-

recently become available. These cover the distribution

ern Siberia. The Kola Peninsula and the Taymir Peninsula

area of SO2 emissions from the Cu-Ni smelters in Nikel,

both receive acidifying compounds from major local point

Zapolyarnyy and Monchegorsk on the Kola Peninsula,

sources; deposition in these areas has been, and is still,

and almost pristine areas of northern Finland (Reimann et

high. There is a large amount of information about the ef-

al., 1998a; Salminen et al., 2004). The survey carried out as

fects of acidic deposition on soils on the Kola Peninsula but

part of the Kola Ecogeochemistry Project had a sampling

much less about effects on soils in the Norilsk area. Owing

density of approximately 1 site per 300 km2 and gener-

to the very high SO2 emissions from the Norilsk smelter

ated information about soil acidity status and the most

complex, the acidifying effects are potentially many times

important natural and anthropogenic factors contributing

higher than on the Kola Peninsula. Although the Chukotka

to soil acidity in this region (Reimann et al., 1998a, 2000a;

region may receive large amounts of acidifying pollutants

Kashulina et al., 1998a,b, 2003; Kashulina and Reimann,

42

AMAP Assessment 2006: Acidifying Pollutants, Arctic Haze, and Acidification in the Arctic

2001; Kashulina, 2002). Figure 5.2 shows the area discussed

ing north through the 100 km wide coastal zone. There is

here. The results of the Barents Ecogeochemistry Project,

a 10-fold increase in sodium (Na) and a 2-fold increase in

undertaken five years later and with a lower sampling den-

magnesium (Mg) in ground mosses and the O-horizon

sity, confirmed the overall conclusions of the Kola Ecogeo-

over the same coastal zone (Figure 5.3). This indicates that

chemistry Project, and in addition, provided information

marine aerosols are probably the main factor explaining

about temporal trends in soil acidity in the region.

the pH increase near the coast. The figure also indicates

According to the Kola Ecogeochemistry Project, the

that natural precipitation chemistry can have a significant

pH(H2O) of the organic (O) horizon of podzolic soils in

effect on acidity parameters in the O-horizon.

1995 ranged from 3.2 to 5.6. Although the region has re-

ceived high levels of acidifying deposition for about 60

Bioclimatic factors

years, this wide range in pH cannot be related to the effects

The distribution of Na concentrations (Na is a major ele-

of two of the world's largest SO2 emission sources, which

ment in marine aerosols, but not an important plant nu-

are located on the Kola Peninsula, since an even greater pH

trient) in mosses and the O-horizon (Figure 5.3) suggests,

range (3 to 6) has been reported as typical for the O-horizon

however, that the influence of marine aerosols is only re-

of podzols in background areas (Targulian, 1971).

sponsible for the southnorth pH gradient in the O-horizon

within a distance of 200 km from the coast. The minor

increase in pH between 200 and 500 km from the coast

5.1.1.1. Natural factors affecting soil acidity

coincides with a slight increase in Mg and calcium (Ca)

concentrations (Mg and Ca are both important plant nu-

Marine input of base cations

trients) (Figure 5.3). The southward decrease in exchange-

There is a relatively strong decreasing trend (0.6 pH units)

able Ca and especially Mg concentrations in the O-horizon

in the acidity of the O-horizon along a southnorth gradi-

is probably due to increasing uptake and utilization by

ent running through the background area (from the Arctic

plants. Thus, the change in bioclimatic factors (climate +

Circle to the coast of the Barents Sea) of northern Finland

vegetation) on moving from south to north may also affect

(Figure 5.3) (Reimann et al., 2000b; Kashulina et al., 2003).

the distribution of acidity in the O-horizon in the region

The sharpest increase in pH (0.4 pH units) occurs on mov-

(Kashulina et al., 2003).

D

0 km

50

100

Honningsvåg

Vardø

N O R W A Y

Vadsø

Lakselv

Kirkenes

Barents Sea

Petschenga

Nikel

Zapolyarnyy

F

E

Severomorsk

Murmansk

Kola

Allarechka-Vostok

Gremyakha-Vyrmes

Ivalo

Lovnozero

F I N L A N D

R U S S I A

Olenegorsk

B

A

Monchegorsk

Revda

Saattopora

Suurikuusikko

Kirovsk

Kovdor

Kittilä

Keivitsa

Apatity

Pahtavaara

Mine, in production

Mine, closed down

Kandalaksha

Important mineral

Alakurtti

occurrence, not developed

Umba

35°30'E

Smelter, production

of mineral concentrate

24°E

Arctic Circle

White Sea

City, town, settlement

C

Rovaniemi

Project boundary

Figure 5.2. The Kola Ecoregion survey area and major industrial centers. The lines AB, CD, and EF mark the transects shown in Figures 5.3,

5.4, 5.5, 5.7, and 5.9.

43

Chapter 5 · Effects on Terrestrial Ecosystems

Site-specific and temporal variation

from other industrial sources) supply enough base cations

All the soil acidity parameters showed very high site-spe-

to maintain precipitation at a less acidic level than that re-

cific variation (Figure 5.3). For instance, pH at two adjacent

corded in northern Finland. Current emissions of nitrogen

sites in background areas differed by more than one pH

dioxide on the Kola Peninsula are low and have little or

unit. Acidity in the O-horizon can vary within the same

no effect on precipitation acidity; nitrate concentrations in

site by more than one pH unit over the year (Levina, 1969).

precipitation are low and relatively uniform throughout

Thus, spatial and temporal variation in pH in the O-horizon

the area (Tikkanen and Niemelä, 1995; Kashulina et al.,

may be greater than any natural trends at the regional level.

1998a). Thus, the area where the soil can be affected by

Site-specific characteristics and/or processes can have a

acidified rain on the Kola Peninsula is limited to restricted

stronger deterministic effect on soil acidity status at an

zones around the smelters. The contribution played by the

individual site than any other regional factors (Kashulina

direct adsorption of SO2 on the soil surface on the Kola

et al., 2003).

Peninsula needs to be investigated, however.

Monchegorsk area

5.1.1.2. Sulfur dioxide emissions and soil acidity

The westeast transect of pH in the O-horizon, running

The O-horizon of podzols is directly influenced by the

through the area occupied by the Monchegorsk smelter

input of ions and cations in precipitation. In the study

(Figure 5.4), indicates that emissions from industrial ac-

area the organic material in the O-horizon has a lifetime

tivities at Apatity (mining and processing of alkaline rocks

of around 20 to 50 years. As a result, it `integrates' the ef-

mined at Kirovsk near Apatity), located 40 km south-east

fects of pollutant deposition over a relatively long period,

of Monchegorsk, have increased the pH by 0.3 units. These

and the cumulative effect of acidifying pollutants can be

emissions also affect the pH of the surface soil close to the

considerable. According to Kashulina et al. (2003), precipi-

Monchegorsk smelter, and are still detectable at the Rus-

tation acidity is affected by SO2 emissions only within a

sian/Finnish border to the west. The atmospheric origin

radius of 30 km around the smelters. In other parts of the

of this increase in pH is supported by the distribution of

Kola Peninsula, the emissions of base cations (derived from

base cations in moss (Figure 5.4).

the smelters, marine aerosols, and basal and alkaline dust

pH in O-horizon

pH in O-horizon

6

a

6

Monchegorsk

Apatity

a

5

5

4

4

C

3

D

A

3

B

Exchangeable base cations in O-horizon, mg/kg

Exchangeable base cations in O-horizon, mg/kg

10000

10000

b

b

C

Ca

Ca

1000

1000

K

K

Mg

Mg

100

100

Na

Na

C 10

D

A 10

B

Total base cations in moss, mg/kg

Total base cations in moss, mg/kg

10000

c

10000

c

K

K

Ca

Ca

1000

Mg

1000

Mg

100

100

Na

Na

C 10

D

A 10

B

7350

7450

7550

7650

7750

7850

350

450

550

650

750

850

Northing, km

Easting, km

Figure 5.3. Transect southnorth across the survey area near the west-

Figure 5.4. Transect westeast across the survey area and through the

ern boundary in 1995 (CD on Figure 5.2), showing: (a) pH in a water

industrial zone centered on Monchegorsk and Apatity in 1995 (AB

extract of the O-horizon; (b) ammonium acetate extractable (pH 4.5)

on Figure 5.2), showing: (a) pH in a water extract of the O-horizon of

base cation concentrations in the O-horizon; and (c) total base cation

podzol soils; (b) exchangeable base cation concentrations in the O-ho-

concentrations in mosses (Kola Ecogeochemistry Project, Kashulina

rizon of podzol soils; and (c) total base cation concentrations in mosses

et al., 2003).

(Kola Ecogeochemistry Project, Kashulina et al., 2003).

44

AMAP Assessment 2006: Acidifying Pollutants, Arctic Haze, and Acidification in the Arctic

The distribution of exchangeable Ca (the dominant

Nikel/Zapolyarnyy area

base cation) in the O-horizon along the transect follows the

Further north, the variation in pH in the O-horizon along

same pattern as for pH (Figure 5.4). However, there is no

an eastwest transect through Nikel and Zapolyarnyy is

corresponding trend for potassium (K) or Mg. This could

less than 0.2 pH units (Figure 5.5). There is a very slight

be partly due to the increased leaching into stream water,

(<0.1 pH units) decreasing trend near Nikel, due to a small

observed within 30 km of Monchegorsk (Kashulina et al.,

number of low pH values near Nikel. Correspondingly,

2003). However, the increase in total Mg in mosses (Fig-

the slightly increasing trend near Zapolyarnyy is due to a

ure 5.4) and the O-horizon near Monchegorsk (Reimann

number of relatively high pH values. The eastern end of

et al., 1998a) is in agreement with the increased deposition

the transect has slightly higher pH values than the western

of Mg in the area. The decrease in the exchangeable Mg

end. The distribution of marine-derived cations (Na and

concentration may be associated with low solubility of

Mg) in mosses and the O-horizon indicates an increasing

Mg in anthropogenic particulate material deposited on

maritime influence towards the east, starting near Nikel

the O-horizon.

(Figure 5.5). The western section of the transect is more

A low pH (although within the natural range of pH

inland, while the eastern section ends at the Barents Sea

variation) and extremely low base cation concentrations

coast. In addition to marine-derived deposition, the Zapol-

(Figure 5.4) are characteristic of soils at a number of sam-

yarnyy area receives alkaline dust from opencast mining

pling sites in the immediate vicinity of the Monchegorsk

(Reimann et al., 1997).

smelter where the vegetation cover has been completely

Generally, it appears that the sources of base cations are

destroyed. Low pH values were also reported in case or

sufficient to prevent acidification of the O-horizon, and to

gradient studies within a distance of 5 km from the smelt-

maintain relatively constant pH and base cation concentra-

ers on the Kola Peninsula (Chertov et al., 1993; Koptsik

tions in the vicinity of Nikel and Zapolyarnyy. As is the

and Muchina, 1995; Kashulina et al., 2003). No changes

case for Monchegorsk, only a small number of low values

in soil acidity were found in a gradient study within a

were observed in the immediate vicinity of Nikel/Zapol-

distance of 10 to 80 km from Monchegorsk (Tikkanen and

yarnyy, especially at sites where the vegetation cover has

Niemelä, 1995).

been severely damaged.

5.1.1.3. The role of overburden and

bedrock chemistry

pH in O-horizon

6

Nikel Zapolyarnyy

The simultaneous emission of fly ash by the smelters and

a

associated power plants, and the alkaline nature of the

overburden and bedrock in some areas near the emission

5

sources, are frequently used to explain the lack of wide-

spread soil acidification on the Kola Peninsula, despite

the very high SO2 emissions (Koptsik and Muchina, 1995;

4

Moiseenko, 1997; Tikkanen and Niemelä, 1995). This raises

the question of whether the relatively high base cation con-

tent of the parent material in some areas near both emission

E

3

F

sources (Monchegorsk and Nikel/Zapolyarnyy) can influ-

ence the chemistry of the O-horizon and counteract the

Exchangeable base cations in O-horizon, mg/kg

acidifying effect of the emissions. Relatively poor correla-

10000

tion has been found between the element concentrations in

b

the parent material (C-horizon) and the O-horizon imme-

diately around the Nikel/Zapolyarnyy smelters (Reimann

Ca

1000

et al., 1998b). Base cation concentrations in the O-horizon

K

at all the sampling points show a much closer relation-

Mg

ship with the corresponding concentrations in mosses (the

100

chemistry of which is primarily determined by atmospheric

inputs) (Figures 5.3 to 5.6), than with those in the C-horizon

Na

(Kashulina et al., 2003). Thus, the distribution of acidity in

E 10

F

the O-horizon in the region is mainly determined by the

atmospheric input, and the geological influence is hardly

detectable in the relatively high atmospheric base cation

Total base cations in moss, mg/kg

10000

deposition gradient on the Kola Peninsula. Fly ash from the

c

K

smelter complexes is not the most important source of base

Ca

1000

Mg

100

Figure 5.5. Transect westeast across the survey area and through the

Na

industrial zone centered on Nikel and Zapolyarnyy in 1995 (EF on

Figure 5.2), showing (a) pH in a water extract of the O-horizon of pod-

E 10

F

zol soils; (b) exchangeable base cation concentrations in the O-horizon

350

450

550

650

750

850

of podzol soils; and (c) total base cation concentrations in moss (Kola

Easting, km

Ecogeochemistry project, Kashulina et al., 2003).

45

Chapter 5 · Effects on Terrestrial Ecosystems

Total Ca (C-horizon), mg/kg

Total Ca in moss, mg/kg

10000

10000

1000

1000

100

100

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Exchangeable Ca (O-horizon), mg/kg

Exchangeable Ca (O-horizon), mg/kg

Total Mg (C-horizon), mg/kg

Total Mg in moss, mg/kg

100000

100000

10000

10000

1000

1000

100

100

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

Exchangeable Mg (O-horizon), mg/kg

Exchangeable Mg (O-horizon), mg/kg

Figure 5.6. Ammonium acetate extractable Ca and Mg in the O-horizon of soils (x-axis) vs. their total concentrations (aqua regia extractable) in

the C-horizon of soils and in moss in 1995 (Kola Ecogeochemistry project, Kashulina et al., 2003).

cations in deposition on the Kola Peninsula (Kashulina et

do, however, suggest that there is elevated deposition of

al., 2003). Alkaline dust from the apatite fertilizer plant,

Al into the O-horizon near Nikel/Zapolyarnyy (alkaline

marine aerosols, and alkaline dust from open-cast mining

rock dust from the opencast mine) and near Apatity (apat-

appear to be the major sources of base cation deposition

ity-nepheline dust). The Al concentrations in precipitation

on forest soil in the western part of the Kola Peninsula.

increase to such an extent immediately around the smelt-

The current rate of base cation emissions is sufficient to

ers (Reimann et al., 1997; de Caritat et al., 1998), that Al

maintain soil acidity parameters at levels that are even

is a major cation (in equivalent terms) in rain and snow

less acidic than, for example, in northern Finland. The only

(Kashulina et al., 2003). Thus, the relatively high exchange-

areas with increased soil acidity and exchangeable base

able Al concentrations in the soil and percolation water

cation depletion are in the severely damaged ecosystems

reported near Monchegorsk (Motova and Nikonov, 1993;

immediately around the smelters.

Lukina and Nikonov, 1996) are more likely to be associated

with basal lithology and increased deposition than to the

Exchangeable aluminum

impacts of SO2 emissions.

The major factor governing the distribution of exchange-

The aluminum:base cation (Al:BC) ratio in the O-ho-

able aluminum (Al) in the O-horizon on the Kola Peninsula

rizon (Figure 5.7) shows extremely high spatial variation.

appears to be the bedrock geology (Kashulina et al., 2003).

The highest values occur around Apatity (apatite-nephe-

Aluminum concentrations in the C-horizon along the

line, syenite) and in soils overlying the meta-sedimentary

transect running through the major SO2 emission source

rocks of northern Norway. The Al:BC ratio in the O-horizon

areas (Figure 5.7) are more similar to the concentrations

shows a good correlation with the total Al concentration in

in the O-horizon than to the moss concentrations (Figure

the C-horizon (r = 0.73), and so the geology is therefore the

5.4). The Al concentrations in mosses along the transect

main factor determining the Al:BC ratio in the O-horizon

46

AMAP Assessment 2006: Acidifying Pollutants, Arctic Haze, and Acidification in the Arctic

Al in O-horizon, mg/kg

Al in O-horizon, mg/kg

100000

100000

Monchegorsk

Apatity

Nikel Zapolyarnyy

a

10000

Total Al

10000

Total Al

1000

1000

Exchangeable Al

100

100

Exchangeable Al

A

10

B

E

10

F

Al in C-horizon and moss, mg/kg

Al in C-horizon and moss, mg/kg

100000

100000

b

C-horizon

C-horizon

10000

10000

1000

1000

Moss

Moss

100

100

A

10

B

E 10

F

Exchangeable Al:(Ca+Mg+K+Na) ratio in O-horizon

Exchangeable Al:(Ca+Mg+K+Na) ratio in O-horizon

10

10

c

1

1

0.1

0.1

A

0.01

B

E 0.01

F

350

450

550

650

750

850

350

450

550

650

750

850

Easting, km

Easting, km

Figure 5.7. A comparison of the two westeast transects across the survey area in 1995 (AB and EF on Figure 5.2), showing changes from east

to west in (a) total Al (nitric acid) and exchangeable Al concentrations in the O-horizon; (b) total Al concentrations in moss and Al (aqua regia

extracts) concentrations in the C-horizon; and (c) the exchangeable Al:(Ca+Mg+K+Na) ratio in the O-horizon (Kola Ecogeochemistry Project,

Kashulina et al., 2003).

(Kashulina et al., 2003). Emissions affect the Al:BC ratio in

5.1.1.4. Connections between soil condition

the soil only within the immediate vicinity of the smelt-

and ecosystem quality

ers. Furthermore, this appears to be an indirect effect of

pollution via damage to the ecosystem. Elevated Al:BC

Soil acidity

ratios also occur in the completely destroyed ecosystems

The distribution of the major acidity parameters in the vari-

(Figure 5.8).

ous classes of ecosystem damage (Kashulina et al., 2003)

47

Chapter 5 · Effects on Terrestrial Ecosystems

CDF, %

CDF, %

100

100

80

80

60

60

40

40

Damage

FIN No damage

RUS No damage

20

20

RUS Depressed

RUS Strong

RUS Complete

0

0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

100

1000

10000

pH

Ca, mg/kg

100

100

80

80

60

60

40

40

20

20

0

0

10

100

1000

10000

100

1000

10000

Mg, mg/kg

K, mg/kg

100

100

80

80

60

60

Figure 5.8. Cumulative distribution

functions (CDF, %) of pH (water ex-

traction), exchangeable Ca, Mg, K, and

40

40

Al concentrations and the exchangeable

Al:(Ca+Mg+K+Na) ratio in the O-hori-

zon in the `no visual damage' zone in

20

20

Finnish Lapland and for various classes

of ecosystem damage in the western

part of the Kola Peninsula in 1995 (Kola

0

0

1

10

100

1000

0.01

0.1

1

10

Ecogeochemistry Project, Kashulina et

al., 2003).

Al, meq/kg

Al:(Ca+Mg+K+Na)

shows that the onset of ecosystem damage (and even of

Niemelä, 1995). A deterioration in the nutrient status of

serious ecosystem damage) on the Kola Peninsula occurs

the soil on the Kola Peninsula has occurred only in the

where there is a more favorable (higher pH and base cation

completely destroyed ecosystems around the smelters.

concentrations) acidity status in the O-horizon compared

There is also a decrease in phosphorus concentrations in

with background areas in northern Finland (Figure 5.8).

the seriously damaged ecosystems within a radius of 30

In contrast, severe ecosystem damage appears to be a

km around the smelters. Manganese concentrations below

prerequisite for soil acidification to appear on the Kola

the deficiency level only occurred at sites with serious or

Peninsula.

complete destruction of the ecosystems (Kashulina, 2002).

Furthermore, the depletion of major nutrients is not a spe-

Plant nutrients

cific reaction of the ecosystem to acidifying deposition.

In addition to base cations (Ca, Mg, K) and other impor-

Thus, the indirect effect of acidifying pollutants on the

tant nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus), depletion of

condition of ecosystems via soil acidification and nutrient

some other nutrients (e.g., manganese (Mn) and zinc (Zn))

depletion does not appear to be the main factor affecting

is regarded as one of the detrimental consequences of acidi-

forest ecosystem condition on the Kola Peninsula. The di-

fying deposition on ecosystems (Galloway, 1995). A sharp

rect effects of SO2 on the vegetation (Aamlid et al., 1995;

decrease in some nutrients (Mn, Zn, Mg) has been reported

Tikkanen and Niemelä, 1995; Kashulina et al., 2003) is a

in severely damaged ecosystems around the smelters on

much more likely explanation for the widespread dam-

the Kola Peninsula (Lobersli and Venn, 1995; Tikkanen and

age to ecosystems on the Kola Peninsula. The significant

48

AMAP Assessment 2006: Acidifying Pollutants, Arctic Haze, and Acidification in the Arctic

increases in the concentrations of some other pollutants

Devonian calcareous and dolomitic marls, and sulfate-

(e.g., nickel, cobalt, cadmium, silver, arsenic, lead, copper

rich evaporates and lower Carboniferous shallow water

and others) of up to a few orders of magnitude in the soil

limestones. Westward from Norilsk the bedrock changes

near the major emission sources (Räisänen et al., 1997; Rei-

and mainly includes intermediate and more acidic types

mann et al., 1998a; Äyräs and Kashulina, 2000) is obviously

of rock.

contributing to the widespread ecosystem damage.

In 2001, water and soil samples were collected from

ten sites in the Norilsk industrial area and in the uncon-

taminated area to the east of the industrial zone. Stream

5.1.1.5. Temporal trends in soil acidity

water samples were collected from each site and complete

A comparison of soil acidity parameters near the Monche-

soil profiles were collected from two sites one in the in-

gorsk smelter in 1995 (Reimann et al., 1997; Kashulina et

dustrial area and the other in the clean background area.

al., 2003) and 2000-2001 (Salminen et al., 2004) showed no

Organic layer samples were also taken from two sites. The

clear changes in the exchangeable Ca concentration in the

sampling and analytical procedures are as reported by Gre-

O-horizon (Figure 5.9). The values obtained in the sparser

gorauskiene et al. (2000) and Salminen and Gregorauskiene

sampling network in 2000 are within the range of spatial

(2002).

variability reported for 1995.

The minerogenic soils that have developed on the

weathering crust of basalt (Lake Lama) have pH values

ranging from 5.1 to 6.2, and the soils that have developed

5.1.2. Acidification and the acidity status

on calcareous sedimentary rocks (Norilsk) from 7.1 to 8.6.

of soils in the Norilsk area

These values are considerably higher than the respective

values reported for Monchegorsk (Table 5.1). The buffer-

The Norilsk mining area is one of the largest point sources

ing capacity, as indicated by Ca and Mg concentrations, is

of sulfur and certain heavy metals in the northern Arc-

much higher in Norilsk than in Monchegorsk. The soils in

tic (AMAP, 1998). Annual sulfur emissions were around

the Norilsk area cannot be considered sensitive to acidifica-

1 million tonnes between 1985 and 2000 (Ekimov et al.,

tion; the pH of the organic layer in the Norilsk industrial

2001), while annual nickel and copper emissions were up

area was as high as 6.4. However, the Cu and Ni values of

to 1300 and 2800 tonnes, respectively. These emissions are

the organic layer are at the same level as in Monchegorsk

more than ten times higher than emissions reported for the

(1370-2820 mg/kg), due to the smelter emissions. The cor-

Monchegorsk smelter on the Kola Peninsula (MRCENR,

responding concentrations in the Lake Lama area are much

1995; Ekimov et al., 2001). Since 2000, there have been no

lower (72-82 mg/kg). However, even the concentrations in

reported changes in the volume of metal production or

the Lake Lama area are higher than the median values (5.9-

any investments to decrease emissions. SO2 emissions for

7.9 mg/kg) reported for large areas of the Kola Peninsula

Norilsk were 2118 kt for 1992 and 1847 kt for 2003.

(Salminen et al., 2004).

The effects of emissions on the soil are partly deter-

mined by climate. Owing to the presence of permafrost in

the region, chemical processes can only occur in the upper-

5.1.3. Effects on soil micro-organisms

most part of the soil, and because of the long winter (9 to 10

months) the period favorable for chemical changes is short.

Soil acidification and the deposition of sulfur and heavy

However, the uppermost part of the soil profile is strongly

metals can influence soil micro-organisms via several routes.

affected by the emissions of sulfur and heavy metals.

First, a decline in pH and the accumulation of pollutants in

Basalts with a basic chemical composition character-

the soil may directly reduce microbial growth and activity

ize the bedrock in the Norilsk area and in the neighboring

(Bååth, 1989). Second, pollutants may indirectly harm the

Putorana Mountains. According to Naldrett et al. (1992),

symbiotic and rhizosphere micro-organisms by decreasing

the sulfide ore deposits in the Norilsk area are hosted by

the amount of photosynthesizing foliage of their hosts.

a large flood basalt formation that erupted in the Devo-

This, in turn, reduces carbon flow to the roots and myc-

nian and Carboniferous sedimentary rocks. The age of the

orrhizal fungi (which are dependent on carbon received

basalt is 251 million years. It consists of picritic, basaltic,

from the host) and to rhizosphere microbes (which are

and tholeitic lavas. Today the basalts form the mountains

negatively affected both by a reduction in the availability of

(the Putorana Mountains) and sedimentary rocks (which

suitable environment due to reduced root biomass and by a

are not metamorphosed but eroded deeper) fill the valleys

decline in the amount of carbohydrate exudates produced

(e.g., in the Norilsk area). These sedimentary rocks include

by the roots). Direct and indirect impacts of acidification

Ca in O-horizon, mg/kg

1995

2000 - 2001

10000

1000

100

pH=4.4

Figure 5.9. Transect westeast across the

survey area (AB on Figure 5.2) show-

ing exchangeable Ca in the O-horizon of

A 10

B

podzol soils in 1995 (Kola Ecogeochem-

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

-50

-100

-150

istry Project) and from 2000 to 2001 (Bar-

Distance from Monchegorsk, km

ents Ecogeochemistry Project).

49

Chapter 5 · Effects on Terrestrial Ecosystems

Table 5.1. Element concentrations in soil horizons in the Monchegorsk (Kashulina and Gregorauskiene, 2000), Norilsk, and Lake Lama areas.

Sites/

Lowest

Ca

Mg

Cu

Ni

S

horizon

depth

pH

LOI

C

(mg/kg)

(mg/kg)

(mg/kg)

(mg/kg)

(mg/kg)

(cm)

(%)

(%)

Total

AR

Total

AR

AR

AR

Total

Monchegorsk

Oer

0

3.90

20.50

11.60

792

532

1370

2030

446

OEer

3

4.39

5.79

3.11

39800

614

37300

443

366

541

122

Bs

20

42400

BC1

40

4.78

3.72

0.92

49900

3310

48200

4850

52.0

72.9

175

2BC2

82

5.42

2.10

0.47

54900

3110

43100

4540

62.2

60.3

95.4

Norilsk

O

5-6

6.40

42.90

22.90

23600

7340

2180

2820

3580

B1

13

7.10

7.96

1.61

43100

12800

24200

8390

64.5

45.0

274

B2

25

7.60

9.36

2.32

44200

13100

27400

8290

50.3

37.0

173

BC

49

8.60

5.35

0.81

62900

25600

29200

9410

50.6

31.0

122

BCk2

70

8.60

5.96

1.07

73900

32900

30900

11100

53.5

32.5

<100

Lake Lama

O

4

4.00

65.20

32.30

3900

2980

81.9

72.4

1080

E

3

4.30

25.10

12.80

4140

3560

30.9

18.4

B

7

5.10

20.30

5.31

31600

7980

22800

8650

47.9

41.6

198

BC

19

5.40

13.70

2.91

37500

9750

23000

10100

58.1

42.3

198

BC2

41

6.00

7.68

1.10

43800

13400

25800

10900

66.5

39.7

124

C

70

6.20

6.00

0.70

50700

15800

29000

10800

56.1

36.6

157

LOI: loss in weight on ignition; AR: aqua regia extractable concentration.

and heavy metals include species-specific effects, leading

communities have also been found in taiga forests around

to shifts in fungal species composition. Third, pollutants

the Kostamuksha iron pellet plant (Zaguralskaya and

often reduce the amount of litter produced by vegetation,

Ziabchenko, 1994) and in subtundra forests of the Taymir

and also change its composition. In addition, the direct

Peninsula affected by the Norilsk nickel-copper smelter

effects of acidifying pollutants on soil invertebrates, re-

(Kirtsideli et al., 1995). Intriguingly, rhizosphere of severely

sulting for example in the disappearance of earthworms

damaged larches near Norilsk contained 10 to 100 times

in polluted areas (section 5.3.2), can affect the mechanical

more micro-organisms than healthy larches in unpolluted

degradation of litter. Both the amount and composition of

regions; this phenomenon presumably resulted from the

the litter, as well as changes in the degradation processes

development of saprotrophic microbiota that benefit from

of soil organic matter, may have several impacts on soil

root decline (Raguotis, 1989).

decomposer activity and diversity.

Fluoride deposition originating from the Kandalaksha

In the Arctic, relatively few studies have been carried

aluminum smelter caused slight alkalinization of the soil

out on the impacts of acidifying pollutants on soil micro-

and altered the community composition of soil fungi, al-

organisms. The adverse effects on soil microbial biomass

though no effects on the biomass of soil bacteria and fungi

and activity seem to be concentrated in relatively restricted

were found (Evdokimova, 2001). However, a more detailed

areas around the nickel-copper smelters where there are

investigation revealed a significant (by a factor of eight)

high levels of heavy metal deposition. For instance, Ohto-

decline in fungal biomass near Kandalaksha (Evdokimova

nen and Väre (1996) reported no detectable changes in soil

et al., 2004).

microbial activity and biomass parameters at distances of

Acidification may not necessarily affect the basidio-

no more than 14 km from the smelter complex at Nikel. On

mycete and ascomycete ectomycorrhizal fungal symbionts

the other hand, soil microbial activity and biomass were

of forest trees, as they are well adapted to naturally acidic

reported to be extremely reduced near Monchegorsk. For

conditions in forest soil (Smith and Read, 1997). However,

example, basal respiration of micro-organisms at sites 8

a decrease in ectomycorrhizal colonization in the roots of

and 10 km from the Monchegorsk smelter was 5 and 8 g

forest trees has been found in response to soil acidifica-

carbon dioxide (CO2) per gramme of organic matter (OM)

tion (Danielson and Visser, 1989; Holopainen et al., 1996;

per hour, respectively, while at sites 36 km or more the

Brunner, 2001). Emissions from the Monchegorsk smelter

basal respiration was 16 to 40 g CO2/g OM/hr. Micro-

have been reported to negatively affect the diversity of

bial biomass was 2.2 and 2.4 C/g OM at nearby sites, and

ectomycorrhizal fungi (Isaeva, 2004).

2.4-5.6 C/g OM at more distant sites (Ohtonen and Väre,

Studies on the effects of acidifying pollution on arbus-

1996). Also, the diversity of microfungi (Lebedeva, 1993;

cular mycorrhizal (AM) colonization in herbs and grasses

Evdokimova, 2000), algae, and prokaryotes (non-spore

in the Arctic are even fewer than those dealing with ec-

forming gram negative bacteria, cyanobacteria and strep-

tomycorrhizal symbionts of trees. There appears to have

tomycetes) (Evdokimova, 2000) in forest soils decreased

been only one survey (Ruotsalainen et al., 2006) on root

moving towards the pollution source. In another study

colonisation in Deschampsia flexuosa, a common perennial

(Nikonov et al., 2001), populations of prokaryotes in the

grass that is tolerant of both acidification and heavy metals.

soils of Norway spruce stands were found to increase, and

There was a decrease in hyphal colonization of both AM

populations of eukaryotes to decrease, moving towards

and DSE (dark septate) fungi with increasing pollution

Monchegorsk. Deterioration of the forest soil, leading to

levels. In contrast, DSE microsclerotia were more abundant

losses in soil organic matter and nutrients, was assumed to

in highly polluted sites, possibly indicating the strategy of

be connected to the adverse effects of heavy metals on soil

these fungi to survive and disperse from unfavorable envi-

fungal populations in drier Scots pine forests (Polyanskaya

ronments. Severe damage to field layer vegetation creates a

et al., 2001). Changes in the composition of soil microbial

patchy environment, such as the industrial barrens around

50

AMAP Assessment 2006: Acidifying Pollutants, Arctic Haze, and Acidification in the Arctic

Monchegorsk, and under these conditions AM fungi may

annual average modeled SO2 concentrations of 15 to 40

have difficulties dispersing from one plant host to another.

g/m3. External damage on the needles of Scots pine (e.g.,

This may have further impacts on fungal communities in

tip necrosis) and changes in species composition of the

the soil.

lichen communities occurred in areas with annual aver-

The cover of Cladina lichens, which is assumed to be

age modeled SO2 concentrations of 8 to 15 g/m3, and

especially effective at filtering out heavy metals, has de-

the damage area extended to the eastern part of Inari in

teriorated and even disappeared in industrial barrens and

Finland. The total area covered by visible damage zones

declining forests (Tømmervik et al., 1995), and this may

surrounding Monchegorsk, Nikel, and Zapolyarnyy was

accelerate the adverse impacts of acidifying pollutants on

estimated to be around 39 000 km2. Around Monchegorsk,

the activity of soil micro-organisms. The structure of the

chlorosis of pine needle stomata occurred in areas with an-

organic layer has been damaged severely in these areas

nual average modeled SO2 concentrations of 4 to 8 g/m3,

(Rigina and Kozlov, 1999). This is partly due to the loss of

and there were changes in the microscopic structure of pine

living fungal hyphae which, together with the fine roots,

needles and epiphytic lichens where the annual average

normally play an important role in maintaining the struc-

modeled SO2 concentrations were 2 to 4 g/m3 (Tikkanen

ture of this layer.

and Niemelä, 1995).

Thus, changes in ground and field layer vegetation due

In the mid-1990s, the proportion of damaged ecosys-

to acidifying pollution in the Arctic are linked to soil de-

tems in the European Arctic increased steadily from the

terioration and changes in soil microbiology. On the basis

northern boreal forest zone to the tundra. Furthermore,

of sparse information on soil micro-organisms in the Arc-

the same stages of ecosystem disturbance (severe, dam-

tic, the adverse effects of acidifying pollutants seem to be

aged, depressed, no damage) coincided with lower con-

concentrated in restricted areas around the nickel-copper

centrations of the major pollutants in humus in tundra

smelters and to be more strongly linked to the excessive

and in subarctic birch forest ecosystems than in forested

deposition of heavy metals rather than to acidification.

areas (Kashulina et al., 1997). On the other hand, a veg-

The diversity of soil micro-organisms may be affected to

etation study from South-Varanger in eastern Finnmark,

a greater extent or at lower levels of pollution, than the

Norway (Aarrestad and Aamlid, 1999) showed that the

biomass and activity of the soil microbial communities.

`pollution variables' Cu and Ni in humus, Ni in Cladina,

and the modeled atmospheric SO2 concentration, together

only explained around 9% of the species variation after

taking into account variation due to natural environmental

5.2. Effects on vegetation in

variables. The comparisons between sulfur concentrations

the European Arctic

in moss and Ni concentrations in humus at various levels

of ecosystem damage demonstrate that the state of the

ecosystems in the mid-1990s in Norway and Finland had,

The damage zones around Nikel and Monchegorsk on the

with few exceptions, no correlation with the deposition

Kola Peninsula reported in the previous AMAP assessment

of pollutants from the Russian smelters. In Russia, how-

(AMAP, 1998) ranged from forest death to a zone with

ever, pollution strongly influenced ecosystem degradation.

changes in the microscopic structure of epiphytic lichens on-

There, even the `no damage' class had a higher median

ly. The corresponding range in annual average atmospheric

value for Ni and sulfur than for all damage classes in Fin-

SO2 concentrations was from >40 to 2-4 g/m3 (Tikkanen

land or Norway (Kashulina et al., 1997).

and Niemelä, 1995; Tømmervik et al., 1995). Nikel, although

As there have been very few studies on acidification

having a much smaller smelter than Monchegorsk, has had

effects on vegetation in the Arctic since the last AMAP

(for technical reasons) considerably higher SO2 emissions

assessment, this section reviews the few new studies to-

(but lower metal emissions) than Monchegorsk. It is also

gether with the results of studies based on data collected

further north and so, having a harsher climate, the vegeta-

in the early 1990s, but mainly published in the late 1990s or

tion is dominated by subarctic birch forest rather than the

early 2000s. The studies include data on direct and indirect

boreal forests around Monchegorsk (Kashulina et al., 1997).

effects of air pollutants, especially SO2, and both critical

Satellite data showed that the total area affected by air

levels and critical loads are addressed.

pollution (average SO2 concentrations >10 g/m3) around

Nikel increased from 400 km2 in 1973 to more than 3900 km2

in 1988, and remained at this level during the early 1990s

5.2.1. Lichen-dominated and mountain

(Høgda et al., 1995; Tømmervik et al., 1995; see also Aamlid

birch (tundra) ecosystems

et al., 1995; Gytarsky et al., 1997). Furthermore, episodes of

high SO2 emissions had caused changes in the lichen and

The main vegetation types in the northernmost and high

dwarf shrub communities over an additional 1100 km2 in

altitude areas of northern Norway and the Kola Peninsula

1988, the area affected by severe air pollution near Nikel

consist of lichen and dwarf shrub communities. Changes

thus increasing to more than 5000 km2.

in the area with reindeer lichen (Cladina spp.)-dominated

The size of the forest-death area was over 400 km2 in

vegetation (heaths and forests with dwarf birch and moun-

the Nikel-Zapolyarnyy and Varanger regions; the area near

tain birch, Betula nana and B. pubescens ssp. czerepanovii)

the border between Russia and Norway studied in 1988

around the Cu-Ni smelters in Nikel and Zapolyarnyy cor-

(Tømmervik et al., 1995). At Monchegorsk, the forest-death

related with changes in emissions of SO2 between the 1970s

area covered between 400 and 500 km2 and extended more

and late 1990s (Høgda et al., 1995; Tømmervik et al., 1995,

than 10 km to the south and more than 15 km to the north

1998, 2003). Thus, there was a reduction in the areas of li-

of the smelter complex (Mikkola, 1996). The average mod-

chen-dominated mountain heaths and forests from 37% in

eled SO2 concentrations exceeded 40 g/m3 in this area

1973 to 10% in 1992, followed by a slight increase to 12% in

(Tuovinen et al., 1993). Marked defoliation of conifers and

1999 in the border areas of Norway and Russia (Tømmer-

an absence of epiphytic lichens occurred in the area with

vik et al., 2003). Reindeer lichens had completely disap-

51

Chapter 5 · Effects on Terrestrial Ecosystems

peared from around two Ni-Cu smelter complexes on the

emissions decreased (but not reaching 1973 levels before

Kola Peninsula by the 1990s (Kalabin, 1991; Tømmervik

the mid-1990s) (Tømmervik et al., 2003).

et al., 1995), their growth rates reaching normal levels at a

Average SO2 concentrations for the lichen-dominated

distance of 50 to 60 km from the smelters (Helle and Ko-

vegetation (Betula nana-lichen heath and Empetrum-lichen

jola, 1992). In addition to Cladina stellaris, the arctic lichen

types) were 3.5 and 9.2 g/m3, respectively, and were 13.6

Cladonia rangiferina is also sensitive to SO2 and/or metals

g/m3 for heather woodland/partly damaged heather

(Koptsik et al., 2003). Kapitsa and Golubeva (1997) ranked

(Empetrum-Vaccinium type) with a sparse/reduced lichen

the lichens Cladina mitis and Cladonia cornuta among the

cover (Tømmervik et al. 1995, 1998). There were associa-

most sensitive species to anthropogenic pressure, while

tions between the damaged land cover, the industrial

the lichen Cetraria nivalis was ranked as less sensitive, and

barren land, and the SO2 concentration in air at ground

the low bushes Phyllodoce caerulea and Salix glauca were

level and Ni and sulfur concentrations in reindeer lichens.

among the most tolerant species. Gaseous uptake meas-

Average sulfur concentrations in reindeer lichens (C. stel-

urements on lichens are limited, but according to Winner

laris and C. mitis) from Empetrum-lichen type forests and

et al. (1988, cited in Nash and Gries, 1995), SO2 uptake by

Empetrum-Vaccinium type heather woodland/partly dam-

C. rangiferina is at least an order of magnitude greater than

aged heather were 489 and 765 mg/kg, respectively, in

in a typical vascular plant. The lichen-dominated vegeta-

the border areas between Norway (Southern-Varanger)

tion types were, however, not just changed into barrens or

and Russia (NikelZapolyarnyy) in the late 1980s to early

partly damaged vegetation entities, but were also changed

1990s. In the bilberry forests/heaths (V. myrtillus-D. flexu-

into heath (and woodland) vegetation with sparse lichen

osa and Cornus suecica types), the average SO2 concentration

cover and were dominated by dwarf shrubs such as bil-

was 14.9 g/m3 and the lichen sulfur concentration was 644

berry (Vaccinium myrtillus) in the NikelZapolyarnyy and

mg/kg (Tømmervik et al., 1998). The vegetation damage

South-Varanger areas in the early 1990s (Tømmervik et

observed and the slightly elevated sulfur concentrations in

al., 1995, 1998).

lichen thalli may be attributed to both high short-term SO2

The gradual change of lichen-dominated vegetation

concentrations as well as long-term exposure to elevated

between 1973 and 1999 into barrens or sparsely vegetated

sulfur deposition based on the proposed critical level of 10

areas or into other vegetation formations: partly damaged

g SO2 /m3 (annual mean) to be adopted for cyanobacterial

heather-dominated vegetation, bilberry forests/heaths,

lichens (UNECE, 1993, 2004a).

and meadow forests (on better soils in lowland areas) oc-

One of the nine catchments where Reimann et al.

curred mainly between 5 and 3040 km from the smelt-

(2001b,c,d, 2003) studied total sulfur concentrations in the

ers at Nikel and Zapolyarnyy, depending on prevailing

leaves of various species was an arctic tundra catchment

wind directions during the growing season. For example,

in Berlevåg on the Barents Sea coast of northern Norway.

the previous sparsely vegetated coastal mountains have

They did not report air quality and/or deposition data

become more barren due to large emissions of SO2 and

and so could not calculate correlations between air quality

their location within the path of the prevailing winds. On

and/or deposition and plant and soil sulfur concentra-

the other hand, the slight increase from around 10 to 12%

tions. At any rate, their results did not show any effects of

in the lichen-dominated communities (Betula nana-lichen

changes in SO2 emissions from the Kola Peninsula, and/or

heath and Empetrum-lichen types) during the 1990s indi-

SO4 in marine aerosols, on the sulfur concentrations of

cates an improvement in air quality and environmental

plant samples collected in summer 1999. For example, the

conditions for these vegetation formations (Tømmervik

total sulfur concentrations of Hylocomium splendens and

et al., 2003); for example, a decrease from 20 to 10 g/m3

Pleurozium schreberi ranged from 716 to 863 mg/kg and for

in the summer SO2 concentrations at Svanvik in the Nor-

V. myrtillus from 1720 to 2230 mg/kg. They concluded that

wegianRussian border area (SFT, 2002). The significant

total sulfur in moss is largely governed by the input of par-

positive relationship between lichen (Cladina sp.)-domi-

ticulate material (dust), such as metal sulfides (Gregurek

nated forests (Empetrum-lichen type with birches; r=0.84,

et al., 1999), and not by atmospheric SO2 concentrations.

p=0.018) and the significant negative relationship between

The total sulfur concentrations of plant and soil samples in

changes in the area of industrial barrens (r=-0.95, p=0.001),

Berlevåg were similar to those in the Russian catchments

and the changes in SO2 emissions between 1973 and 1999

of Vorkuta and Naryan-Mar, with all three areas showing

may be explained by the response times of the different

large variations in the total sulfur concentrations in leaves

land cover classes to SO2 emissions. There is always a lag

both between species within each area as well as between

in the vegetation response to changes in SO2 emissions and

areas (Figure 5.10, Table 5.2).

in this case the area of lichen-dominated vegetation types

Particulate emissions that contain heavy metals are

decreased and the barrens increased at the same time as

deposited closer to the emission sources than SO2 and

Table 5.2. Median sulfur concentrations (mg/kg dry weight) in plant leaves collected from four northern European catchments in summer 1999

(Reimann et al., 2001c, 2003).

Catchment

Berlevåg

Monchegorsk

Naryan-Mar

Vorkuta

(southern tundra

(moss-lichen shrub tundra

(arctic tundra)

(northern taiga)

with birch and shrub)

with birch and willow)

Moss (Hylocomium splendens)

754

1090

889

824

Blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus)

2025

1710

Cowberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea)

1350

2095

1300

1480

Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum)

1220

1260

1130

1360

Birch (Betula pubescens)

1775

1890

Willow (Salix spp.)

3765

2335

2350

3180

Pine (Pinus sylvestris)

1190

Spruce (Picea abies)

1985

547

52

AMAP Assessment 2006: Acidifying Pollutants, Arctic Haze, and Acidification in the Arctic

1 Vorkuta

Catchments discussed

in this report

Project area boundary

100 0 100 km

Figure 5.10. Location of the catchments included in the Barents Project (Reimann et al., 2003; reprinted from Reimann et al., 2001d).

SO4 (e.g., Gytarsky et al., 1995) and therefore the relative

deposition than H. physodes. The zero zone of lichen cover

importance of the direct and indirect harmful effects of

coincided approximately with the areas where the mod-

sulfur compounds increases with increasing distance

eled annual mean SO2 concentrations reached 25 g/m3.

from the emissions sources. The occurrence of visible SO2

However, sulfur compounds are not the only acidifying

injuries in the leaves (B. pubescens, B. nana, V. myrtillus,

compounds; Hilmo and Larsen (1994) found morphologi-

V. uliginosum) and Scots pine needles (Pinus sylvestris) in

cal changes (discoloration, growth form) in Parmelia sulcata

northeastern Norway close to the Russian border (Aamlid,

at an industrial site in Glomfjord that may be related to

1993; Aarrestad and Aamlid, 1999) (Figure 5.11) has mainly

elevated nitrogen deposition.

been attributed to episodes with high SO2 concentrations

The results of Tømmervik et al. (1998, 2003) on vegeta-

that occur under specific meteorological conditions (Jerre,

tion changes in the area of Pasvik and Zapolyarnyy/Nikel

1994). Hilmo and Larsen (1994), in turn, reported mor-

at the NorwegianRussian border show an increase from

phological differences (growth form, fertility, apothecial

about 7% in 1973 to about 20% in 1979, with a stabilization

morphology, discoloration) in the epiphytic lichens Hypo-

at approximately 30% by 1999 in bilberry and low herb

gymnia physodes and Melaniella olivacea at sites exposed to

vegetation formation and meadow vegetation (bilberry

high concentrations of SO2 in Sør-Varanger compared to

forests/heaths and meadow forests with mountain birch).

lichens at an unpolluted control site. As M. olivacea had a

This change coincided with the decrease in the areas of

larger mean cover on birch stems than H. physodes in the

lichen-dominated vegetation and was mainly due to the

border area between Norway and Russia, and was more

transformation of dwarf shrub (Empetrum hermaphroditum)

frequently found at the plots in the 1991 and 1993 studies

and lichen-dominated vegetation cover types into bilberry

(Aamlid and Skogheim, 2001), it may even be considered

and Deschampsia flexuosa-dominated formations which

more tolerant to the direct and indirect effects of sulfur

appear up to 5 to 40 km from the smelters (Deyeva and

a)

b)

Figure 5.11. Visible (acute) SO2

injuries on (a) birch (Betula pu-

bescens) leaves and (b) Scots

pine (Pinus sylvestris) needles

at Svanvik, Norway, approxi-

mately 10 km northwest of

Nikel (Photos: Dan Aamlid).

53

Chapter 5 · Effects on Terrestrial Ecosystems

Varangerfjorden

1973

Norway

Kirkenes

Finland

N O R W A Y

F I N L A N D

PC

PA PB

RUS-1

RUS-3

PD RUS-2

Nikel Zapolyarnyy

R U S S I A

RUS-0

Monitoring site

NorwayRussia

Figure 5.13. Location of joint Norwegian/Russian sites for intensive

a)

terrestrial monitoring (SFT, 2002).

Maznaja, 1993; Tømmervik et al., 1995, 1998, 2003). With

regard to pollution resistance of mountain birch, studies in

1994

the vicinity of the smelters at Monchegorsk may suggest

phenotypic acclimatization of mature trees to a gradual

Norway

increase in pollution as well as selection for pollution-

Finland

resistant genotypes that may have occurred due to the

exceptionally high emissions pressure over the past few

decades (Valkama and Kozlov, 2001; Kozlov and Zvereva,

2004; Kozlov, 2005).

5.2.2. Coniferous forest ecosystems

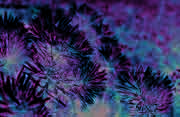

According to Tømmervik et al. (2003), the vegetation cover

that had the highest association (r=-0.94, p=0.001) with

changes in SO2 emissions in the Pasvik and NikelZapol-

yarnyy areas was the mixed birch-pine forests with lichen

content (Figure 5.12). The increase in the area of mixed

pine-birch forests, especially from 1988 to 1999, meant

Norway

b)

Russia

that the area affected by air pollution was reduced. The

most important differences in species composition in the

NikelPasvik area along the NorwegianRussian border

(see Figure 5.13 for the location of the RussianNorwe-

1999

gian vegetation monitoring sites) were related to the loss

of species richness, i.e., a lower abundance of bryophytes

Norway

(e.g., H. splendens, P. schreberi, Dicranum species) and li-

Finland

chens (several Cladonia species) (Aamlid et al., 2000), and

a concomitant increase in the dominance of air pollution

resistant species such as D. flexuosa and E. hermaphroditum

(SFT, 2002; Tømmervik et al., 2003; see also Vassilieva et al.,

1995) (Table 5.3). These differences are explained on the

basis of both the direct impacts of pollution and the indi-

rect soil-mediated processes leading to, for example, soil

0 Unclassified/edge

1 lakes/rivers/sea

2 Exp. heaths/barrens/boulders

3 Mixed pine-birch forests

4 Heather wodland and mires

5 Heather wodlandpartly dam.

6 Lichen dominated forests

7 Lichen dominated heaths

Norway

8 Bilberry forests

c)

Russia

9 Meadow forests

10 Wet bogs/mires

11 Ind. barrens/bare rocks

Figure 5.12. Land cover maps for the PasvikNikel area for (a) 1973,

12 Ind. barrens/damaged veg.

(b) 1994, and (c) 1999 (Tømmervik et al., 2003).

13 Clouds/smoke

54

AMAP Assessment 2006: Acidifying Pollutants, Arctic Haze, and Acidification in the Arctic

Table 5.3. Average number of species within 1 m2 plots in pine forest along a western gradient from Nikel (SFT, 2002). The highest values for each

species group (bold font) indicate the change from lichen- and moss-dominated vegetation to small shrub- and grass-dominated vegetation near

the emissions sources.

Species group

Sample plots and their distance from Nikel

45 km

25 km

16 km

12 km

9 km

6 km

6 km

south

west

west

west

northwest

north

west

Small shrubs

3.5

2.9

3.1

3.1

3.4

4.2

4.0

Herbs

1.9

1.9

1.7

0.8

1.9

2.0

1.1

Mosses

5.1

4.6

4.7

4.7

4.6

1.2

2.1

Liverworts

1.3

1.5

2.0

1.5

1.6

0.7

1.2

Lichens

3.7

4.1

7.5

8.2

3.9

2.3

3.1

All species a

15.4 (24)

14.9 (30)

19.2 (32)

18.7 (31)

15.6 (26)

10.9 (23)

11.5 (17)

a maximum number of species in brackets

acidification and nutrient imbalances (Tømmervik et al.,

However, the cell injuries studied did not show any distinct

1995; Aarrestad and Aamlid, 1999; Koptsik et al., 1999a,b,

relationships with element concentrations in either foliage

2003; SFT, 2002). Furthermore, for example, Pohlia nutans is

or deposited particles (Rautio et al., 1998c).

a moss species that has increased its cover in the most pol-

High variation in the total sulfur concentrations in

luted area. This species, characterized by wide ecological

plant samples collected during the growing season may

amplitude, colonized the emptying litter in industrial bar-

be explained (in addition to species-specific characteristics

ren land in the absence of competition from other (moss)

and differences in gaseous and particulate sulfur deposi-

species more sensitive to pollution (Koptsik et al., 2003).

tion) by nutrient status, pH, and other soil characteristics,

According to Kashulina et al. (1997, 2003), direct ex-

as well as by climate, composition of the vegetation layer

posure to SO2 is the most likely, although not the only

and altitude (Reimann et al., 2001b, 2003). For example,

mechanism of vegetation damage in the eight catchments

despite higher SO2 emissions from the Nikel smelter com-

located on the Kola Peninsula and in northeastern Finland

pared to the Monchegorsk smelter, plants accumulate more

and Norway. The highest sulfur concentrations in plant

sulfur near the latter because of the specific combination

samples in the most polluted sites were usually 2- to 4-fold

of geomorphological and meteorological conditions (Ko-

higher than at control sites (Gytarsky et al., 1995; Äyräs et

ptsik et al., 1999a). It is also well known that plant nutrient

al., 1997; Aamlid et al., 2000; Steinnes et al., 2000; Reimann et

concentrations (including sulfur) vary considerably during

al., 2001a,c). Steinnes et al. (2000) reported a decrease from

and between growing seasons. For example, the average

4270 to 2000 mg/kg and from 2820 to 1420 mg/kg in the

sulfur concentrations of current-year Scots pine needles

mean total sulfur concentration of B. pubescens and E. her-

collected in August-October between 1996 and 1999 were

maphroditum leaves, respectively, on moving from the most

755 to 901 mg/kg at Värriö in the eastern part of Finnish La-

polluted study sites around Nikel to the southernmost sites

pland and 806 to 988 mg/kg at Sammaltunturi (i.e., Pallas)

more close to background conditions in 1991. A decrease

in the western part of Finnish Lapland (Sirkku Manninen,

from around 3500 to 1000 mg/kg, and from around 3400 to

University of Helsinki, unpubl. data). This is why needle

1500 mg/kg in the foliar sulfur concentration of Betula sp.

samples for bioindicator studies mapping the dispersal of

and V. myrtillus, respectively, between the areas closest to

sulfur emissions, as well as the area possibly affected by

the Nikel smelters (<5 km) and background areas (about 30

sulfur deposition, are usually collected in winter, i.e., when

km) was, in turn, reported by Gytarsky et al. (1995). Sulfur

emissions are at their highest and the trees are physiologi-

was also the major element in moss (H. splendens and P.

cally relatively inactive (see e.g., Manninen et al., 1997a,

schreberi 2090-543 mg/kg) and the O and B soil horizons in

1998; Rautio et al., 1998a,b).

the 1995 survey in northern Finland, Norway, and Russia

The latitude-related decrease in the total sulfur concen-

(Äyräs et al., 1997; Kashulina et al., 1997, 2003; Kashulina

tration on moving northward (Reimann et al., 2003) may

and Reimann, 2001, 2002; Reimann et al., 2001a).

be related to the length of the periods during which the

Reimann et al. (2001b,c,d, 2003) measured total sulfur

plants have stomatal uptake of SO2 versus the time when

concentrations in the leaves of several plant species col-

they are exposed to non-stomatal deposition only, as the

lected from nine catchments in northern Europe (Finland,

proportion of (winter) non-stomatal deposition increases

Norway and Russia) in summer 1999. Only Norway spruce

towards the north. The dry deposition of sulfur dominates

(Picea abies) needles showed significantly higher sulfur

in northern areas due to the low precipitation, and dry

concentrations in all samples collected near Monchegorsk.

deposition accounts for about 80% of the total deposition

Correlation between `available' sulfur in surface soil and

(Tuovinen et al., 1993). On the other hand, as most of the

observed foliar sulfur concentrations for all plants growing

plants have a snow-cover for six to seven months of the

in the soils was in general very low. Furthermore, Reimann

year, more than 50% of the total annual deposition will

et al. (2003) concluded that macroscopic and microscopic

deposit onto snow (Kashulina and Reimann, 2002). This

evidence of leaf damage are more reliable indicators of pol-

means that the sulfur concentrations of mosses and lichens

lution impact than foliar sulfur concentration. In a study

which are thallophytes (i.e., they have no roots but ob-

carried out in the early 1990s on Scots pine, Rautio and

tain all their nutrients through their above-ground parts

Huttunen (2003) also found a weak relationship between

as ions dissolved in water rain and melting snow), may

element concentrations in the soil and internal foliar con-

give a different picture about the rate and distribution of

centrations. A factor representing high foliar levels of Ni,

sulfur emissions compared to that given by foliar sulfur

Cu, and sulfur, and low levels of Zn and Mn, was found to

analyses of evergreen conifers. Steinnes (1995) pointed out

explain most of the variation in the number of needle age

that it may, however, be feasible to achieve representative

classes and tip necrosis. The macroscopic injury variables

results (at least for heavy metals) by carefully selecting the

(including stomatal chlorosis and other discolorations) cor-

sampling site for moss in order to avoid interference from

related clearly with the modeled SO2 concentration in air.

wind erosion or surface water flow. On the other hand,

55

Chapter 5 · Effects on Terrestrial Ecosystems

the lower growth rate of mosses in arctic regions may be

reductions at the smelters on the Kola Peninsula. There has

expected to lead to greater uptake of airborne trace ele-

also been extensive forestry in the southern part of the Pas-

ments per unit weight than in mosses at more southerly

vik area and this has led to reductions in lichen cover (suc-

latitudes. Furthermore, the different growth structure of

cession) and pine forests. Severe desiccation of the forest

the plant may make it more difficult to accurately define

vegetation close to the smelters at Nikel and Zapolyarnyy

the exposure period.

has led to increasing amounts of dead needles and woody

In addition to the total sulfur concentration of Scots

debris, which in turn has led to more frequent wild for-

pine needles, statistically significant correlations (p<0.001)

est fires (Tømmervik et al., 2003). Moreover, outbreaks by

were found between the annual mean SO2 concentration

caterpillars such as Epirrita autumnata have been followed

and needle sulfate concentration and S:N ratio at the sites

by successions from lichen-dominated vegetation to more

close to Monchegorsk in the early 1990s (Manninen et al.,

dwarf shrub- and grass-dominated vegetation (Lehtonen,

1998) (Table 5.4). Koptsik et al. (1999a, 2001) also found a

1987; Tenow and Bylund, 2000).

marked gradient in the needle total sulfur concentration

Over most of northernmost Europe, the trend towards

and S:N ratio of Scots pine with increasing distance from

a shift in lichen-dwarf shrub dominated forests to more

the Nikel smelters in the early 1990s. The increase in the

grass- and herb-dominated forests, may reflect a situation

S:N ratios towards the Nikel smelters is not just explained

where slow-growing species such as lichens, crowberry

by the increasing needle total sulfur concentrations, but by

(E. hermaphroditum), and cowberry (V. vitis-idaea) are de-

lower nitrogen supply from the soil observed as decreasing

clining due to intensive reindeer grazing (Olofsson et al.,

concentrations of nitrogen in soil organic horizons toward

2001). Tømmervik et al. (2004) also gave climate change (in-

the smelter. In addition to nitrogen concentrations, those

creased precipitation) and long-range transported nitrogen

of ammonium acetate-extractable Mg and K in organic

pollution (increasing nitrogen deposition is also linked to

horizons tended to be lower within several kilometers of

increasing precipitation) as possible accentuators for the

the Nikel smelters compared to remote sites (Koptsik et al.,

increase of birch forests and vegetation types dominated by

1999b, 2001, 2003) as they also were around the Monche-

bilberry, wavy hair-grass (D. flexuosa), the dwarf cornel (C.

gorsk smelters (Lukina and Nikonov, 1999, cited in Zvereva

suecica), and mosses (P. schreberi, H. splendens) in northern

and Kozlov, 2005). With regard to temporal trends related

Norway over the last 40 years.

to the decrease in SO2 emissions and, consequently, in the

Increased nitrogen deposition through precipitation

ambient SO2 concentrations in the border areas of Nor-

and/or deposition of manure (feces) from the reindeer may

way and Russia (Hagen et al., 2005), the results of Koptsik

create unfavorable living conditions for slow-growing spe-

et al. (G. Koptsik, Moscow State University, pers. comm.)

cies. Bobbink et al. (2002) considered an empirical critical

suggested a decrease in the total sulfur concentration of

load of 5 to 10 kg N/ha/yr, based on field manipulations

current-year Scots pine needles from August 1991-1994 to

in which exceedance was indicated by changes in biomass

August 2002. At any rate, as there are differences in foliar

and in the moss layer, reliable for tundra ecosystems. They

responses to elevated sulfur and nitrogen deposition be-

gave the same critical load for arctic, alpine, and sub-alpine

tween coniferous tree species (Manninen and Huttunen,

shrub habitats (with exceedance indicated by a decline

2000; Luyssaert et al., 2005), more research is needed on

in lichens, mosses, and evergreen dwarf-shrub), but its

foliar sulfur and nitrogen fractions and ratios, as well as

reliability was referred to as `expert judgment' (see also

on Mg:N and Ca:Al ratios, in the northernmost areas for

UNECE, 2004a). Recent results from field experiments in

use as indicators of acidification.

an area of northern Sweden with low background nitrogen

deposition and from a large-scale monitoring study, show

that important vegetational changes start to occur when

5.2.3. Reindeer grazing, climate change,

adding low nitrogen doses and that recovery of the vegeta-

nitrogen deposition, and other factors

tion after nitrogen inputs stop is a very slow process. Based

on data from the Swedish research program Abatement

Reindeer grazing is one factor that modifies or interacts

Strategies for Transboundary Air Pollution, Nordin et al.

with the effects of sulfur deposition on vegetation, especial-

(2005) suggested that the critical load should be lowered

ly in northern Norway. According to Gaare and Tømmer-

from the current 10 to 15 kg N/ha/yr to a level of 6 kg

vik (2000), reindeer have grazed down the new `reindeer'

N/ha/yr to protect the biodiversity of the boreal forest

lichens in the period 1992 to 1999, i.e., after the emissions

understorey vegetation. The impact of elevated nitrogen

Table 5.4. Concentrations (mg/kg) and ratios of sulfur and nitrogen in current-year Scots pine needles collected at different distances from the

smelters on the Kola Peninsula showing change along the pollution gradients and seasonal variation in needle chemistry.

Sampling

Total Sa

Organic S

SO4-S

SO4-S/organic Sa

Total N

Total S/Total Na

Reference

Finnish Laplandb

Sep-Oct 1990,

720-1153

479-862

141-361

0.20-0.53

9200-13000

0.032-0.045

Manninen et al.,

Sep 1992

1997b

Monchegorsk-

Apr 1991

856-2548

672-1599

105-1297