Chapter 4

Persistant toxic substances (PTS)

sources and pathways

4.1. Introduction

Chapter 4

4.1. Introduction

4.2. Assessment of distant sources:

In general, the human environment is a combination

Long range atmospheric transport

of the physical, chemical, biological, social and cultur-

Due to the nature of atmospheric circulation, emission

al factors that affect human health. It should be recog-

sources located within the Northern Hemisphere, par-

nized that exposure of humans to PTS can, to certain

ticularly those in Europe and Asia, play a dominant

extent, be dependant on each of these factors. The pre-

role in the contamination of the Arctic. Given the spa-

cise role differs depending on the contaminant con-

tial distribution of PTS emission sources, and their

cerned, however, with respect to human intake, the

potential for `global' transport, evaluation of long-

chain consisting of `source pathway biological avail-

range atmospheric transport of PTS to the Arctic

ability' applies to all contaminants. Leaving aside the

region necessarily involves modeling on the hemi-

biological aspect of the problem, this chapter focuses

spheric/global scale using a multi-compartment

on PTS sources, and their physical transport pathways.

approach. To meet these requirements, appropriate

modeling tools have been developed.

Contaminant sources can be provisionally separated

into three categories:

Extensive efforts were made in the collection and

·

Distant sources: Located far from receptor sites in

preparation of input data for modeling. This included

the Arctic. Contaminants can reach receptor areas

the required meteorological and geophysical informa-

via air currents, riverine flow, and ocean currents.

tion, and data on the physical and chemical properties

During their transport, contaminants are affected by

of both the selected substances and of their emissions.

the combined effects of physical and chemical fac-

It should be noted that reliable and relatively compre-

tors. Persistence in the environment is, therefore,

hensive information on emission sources is currently

one of the most important characteristic in deter-

not available for most PTS. Therefore, an assessment of

mining the ability of contaminants to reach the

long-range atmospheric transport was undertaken for

Arctic. In this respect, PTS, due to their low degra-

substances for which emission source information is

dation rates, are often considered to be `global con-

sufficient to meet modeling requirements, namely,

taminants' subject to long-range transportation.

mercury (Hg), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and

-hexachlorocyclohexane (-HCH). It was considered

·

Local sources: These are located in receptor

that modeling results obtained for these contaminants

region, often in the vicinity of indigenous commu-

could be extrapolated to give a general overview on the

nities. Although transport of contaminants from

situation with respect to long-range atmospheric trans-

local sources to recipients is determined by the same

port of other PTS in the study.

physical and chemical processes as contaminants

from distant sources, there are a wider range of path-

An assessment of mercury, PCB and -HCH pollution

ways and mechanisms that may be involved in the

arising from emission sources in the Northern

case of local sources. For example, mechanisms of

Hemisphere and affecting regions of the Russian

soil contamination from local sources can differ sig-

North inhabited by indigenous peoples, was carried

nificantly, such that effects of local contamination

out for the reference year 1996. This assessment

can be much greater than those resulting from con-

included an evaluation of air concentrations and dep-

tamination from distant sources. In contrast to dis-

osition levels, as well as source-receptor relationships

tant sources, local sources can also affect recipients

for selected regions and for the Arctic as a whole.

through contamination by more readily degradable

Particular attention was given to the fate of contami-

substances as well as the persistent contaminants.

nants in different environmental compartments (air,

Although non-persistent contaminants are beyond

soil, water, etc.). The effect of PCBs and -HCH trans-

the scope of this project, it is important to note that

port via ocean currents, ice cover dynamics, and

the effects of PTS, when combined with those of

`Mercury Depletion Event' (MDE) (Schroeder et al.,

other types of contaminants originating from local

1998) chemistry on Arctic pollution were also exam-

sources, may be substantially increased. Similarly,

ined.

humans exposed to and affected by PTS may be

more sensitive to the acute toxic effects of other less

4.2.1. Climate conditions

persistent contaminants from local sources.

and atmospheric circulation patterns

The climate of the Russian Arctic is characterized by a

·

Contact sources: These comprise the intentional or

lack of solar radiation during the winter, which leads to

unintentional use of chemicals by recipients in every-

very low temperatures. In contrast, solar radiation flux

day household and occupational uses. For example,

in the summer is significant, but temperatures are still

the health of individuals using PTS-containing insec-

not high, as most incoming solar energy is utilized in

ticides for pest control or for the treatment of rein-

the melting of ice and snow. Atmospheric circulation is

deer may be directly affected by the products. A typi-

characterized by cyclonic activity in all seasons, which

cal example of an unintentional contact contaminant

promotes the exchange of air masses between the mid-

source would be the use of paints and insulating mate-

dle and high latitudes. As a result of the prevailing west-

rials containing PTS in the indoor environment.

erly airflows, the Russian Arctic experiences the mod-

34

Chapter 4

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

erating influence of the Atlantic (North Atlantic

Current). This influence is stronger in western parts

than in central and eastern parts. The western Russian

Arctic is therefore warmer, with a much lower temper-

ature variation between winter and summer than that

found in the eastern part of the Russian North, which

is characterized by the more severe climatic conditions.

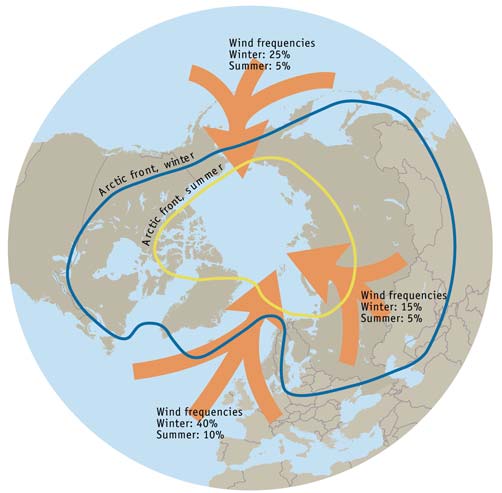

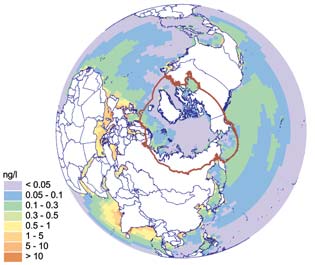

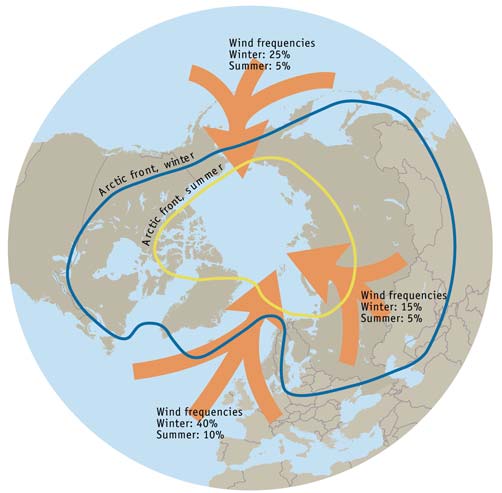

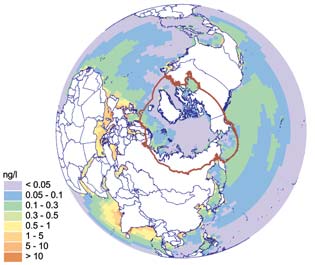

Atmospheric circulation in the Arctic region differs

between winter and summer (Figure 4.1) with the pre-

vailing atmospheric currents in the lower Arctic tropo-

sphere depending upon the location of quasi-station-

ary pressure systems in the Northern Hemisphere, the

Icelandic and Aleutian Lows, and Siberian and North

American Highs.

In winter, due to the geographical position of these sys-

tems, air masses move into the Arctic from Europe in a

northeasterly direction, or from central Asia and

Siberia. Western regions of the Russian North

Murmansk Oblast and the Nenets Autonomous Okrug

Figure 4.1. Mean position of the Arctic air mass in January and July,

(AO) are affected mainly by southwesterly or westerly

and the winter and summer frequencies of winds (AMAP, 1997).

airflows, bringing air masses from Eastern and Central

Europe, as well as from central Russia. In the central

4.2.2. Emission sources

regions Yamalo-Nenets AO, Taymir AO, and the

Emission sources of Hg, PCBs and -HCH were divided

Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) southerly airflows pre-

into several groups according to their geographical

vail, transporting air masses from central Russia, the

location (Figure 4.2). The key criterion used for the

Urals, the south of Siberia and central and eastern

selection of a specific region as an aggregate emission

Asia. Over the easternmost region the Chukchi AO

source was the possible influence of emissions from

northerly airflows predominate in winter.

this region on the Russian North.

In summer, the continental high-pressure systems dis-

appear and oceanic low-pressure systems weaken. Over

the Arctic Ocean, high-pressure systems occur more

frequently than in winter, causing an outflow of Arctic

air in the meridional direction. The European region

comes under the impact of the Azores anticyclone.

Over central Eurasia and the central part of North

America, low-pressure systems dominate. The influx of

air masses to the Arctic mainly occurs over the Aleutian

Islands/Bering Sea region in the east, and from the

North Atlantic, along the north-western periphery of

Azores anticyclone, in the west. Compared with winter,

the northerly component is more frequent in atmos-

pheric transport in summer across all regions of the

Russian Arctic except for Chukotka. Chukotka, during

the summer, is predominantly affected by transport

either from the Pacific Ocean, or from Eastern Asia

and the Russian Far East, some transport from the

north still occurs however.

Figure 4.2. Source regions of the Northern Hemisphere considered

Atmospheric circulation is also responsible for the pre-

in the source receptor analysis.

cipitation pattern in the Russian Arctic. The most abun-

dant annual precipitation takes place in the western part

The number of the selected regions varies for different

and can reach 500-600 mm/y. Annual precipitation

pollutants. For simplicity, generalized names were used

decreases from the west towards the east, and over the

for some regions, e.g., the region identified as `Central

north of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is mainly within

Asia' actually includes central, western, and southern

the range of 100-150 mm/y. In the easternmost part of the

Asia. Selected emission sources regions for the pollutants

Russian Arctic, precipitation is relatively high (300-

under consideration are presented in Table 4.1. Source

600 mm/y), and caused by the southerly transport of air

region boundaries also vary depending upon the contam-

masses from the Pacific Ocean, especially during summer.

inant in question. For example, China and Japan are con-

35

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

Chapter 4

sidered as separate sources for mercury, but included in

Mercury

larger Asian source regions for the other contaminants.

The industrial and urbanized regions of the world

For -HCH, China and India are important enough

account for the majority of anthropogenic mercury

sources to consider their emissions separately, whereas

emissions to the atmosphere. To evaluate the anthro-

Northern Europe was omitted as -HCH emissions in this

pogenic input of mercury to the Northern

region in 1996 were insignificant. The Americas (North

Hemisphere, the most recently available global emis-

and Central) are included as a single source region, due

sion inventory, that for 1995, (Pacyna and Pacyna,

to their greater distance from the Russian North.

2002) was used. The original global emissions dataset

has a resolution of 1°x1° lat./long., with mercury emis-

sions speciated into three chemical forms: gaseous ele-

mental mercury (Hg0), gaseous oxidized mercury

(Hg2+), and particulate mercury (Hgpart). These emis-

sion data were redistributed to a lower resolution

(2.5°x2.5°), suitable for input to the air transport

model employed, assuming uniform distribution over

each grid cell.

The most significant emission sources are in Eastern

Asia, Europe and the eastern part of North America.

Considerable emissions also occur in the Indian sub-

continent and the Arabian Peninsula. The total

amount of anthropogenic mercury emissions in 1995

from the Northern Hemisphere was estimated as 1887

tonnes.

Table 4.1. Regions of the Northern Hemisphere selected as source areas

In order to assess the impact of different mercury emis-

for long range transported pollutants.

sion sources on the contamination of the Russian

North, the entire hemispheric emission field was divid-

Due to their proximity to the Russian North and the sig-

ed into 11 regions: Russia, China, Central Asia, the

nificant polluting influence of some regions of the

Americas, Japan, Southeast Asia, Africa, Eastern

Russian Federation, the territory of Russia was subdivid-

Europe, Western Europe, Southern Europe, and

ed into twelve source regions according to current

Northern Europe. The relative contribution of each

administrative boundaries and to their potential impact

region to total mercury emissions in the Northern

on Arctic ecosystems. The Location of these regions and

Hemisphere is presented in Figure 4.4(a).

abbreviated identification codes is shown in Figure 4.3.

The first five regions (MUR, NEN, YNT, YAK, and

This diagram shows that more than one third (34%) of

CHU) are also considered as the receptor regions.

the total mercury emissions originate in China.

Considerable emissions also originate in Central Asia

(14%), the Americas (11%), Japan (9%), and Russia

(8%). The contribution of other regions specified does

not exceed 7%.

Figure 4.4(b) shows total mercury emissions from differ-

ent regions of the Russian Federation. The most signifi-

cant emission sources are located in the Central-

Chernozem, Volga, and North-Caucasian regions (CVN),

the Ural region (URL), and the Central and Volgo-Viatsky

regions (CVV).

Mercury emissions from natural sources contribute a

MUR Murmansk Oblast;

NWK North-Western region

significant proportion of the total mercury input to the

and Kaliningrad Oblast;

atmosphere. Estimates for the value of natural emis-

NEN The Nenets AO;

CVV Central

and Volgo-Viatsky regions;

sions and re-emissions were based on a literature sur-

YNT The Yamalo-Nenets AO

CVN Central-Chernozem, Volga

vey. Mercury emissions from natural sources were

and Taymir AO;

and Northern Caucasus regions;

YAK The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia); URL Ural region;

apportioned over the Northern Hemisphere on the

CHU The Chukchi AO;

WSB West Siberian region;

basis of the nature of the underlying land/sea surface.

NRT Northern region;

ESB East Siberian and Far-Eastern

Five surface categories were distinguished: ice covered

regions.

land (glaciers, etc), seawater, soil developed from geo-

chemical mercury belts, soils in areas of mercury

Figure 4.3. Aggregated regions of the Russian Federation chosen for source recep

tor analysis. The first five regions listed (MUR, NEN, YNT, YAK, and CHU) are consid

deposits, and other (background) soils. It was assumed

ered as both source and receptor regions, the rest are considered as source regions.

that there is zero mercury emission from ice caps/gla-

36

Chapter 4

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

b

Figure 4.4.

(a) Contribution of different regions of the Northern Hemisphere

to total anthropogenic mercury emissions, (b) total anthropogenic

mercury emissions from different regions of the Russian Federation.

a

ciers. Natural emissions from seawater were distributed

in 1996 were about 80, 23, 16, and 4.5 tonnes, respec-

proportionally to the ocean's primary production of

tively. Congener composition of PCB emissions varies

carbon. Emissions from soil are most significant from

between source regions.

soils occurring over mercury deposits and lowest for

background soils. In addition, the temperature

In order to study the contributions of different source

dependence of emission fluxes was also calculated,

regions in the Northern Hemisphere to the contami-

based on data obtained through measurements.

nation of the receptor-regions in the Russian Arctic, six

main regional sources were identified, based on the

PCBs

emission distribution: Russia, Northwest Europe,

Modeling long-range transport of individual PCB con-

Southeast Europe, the Americas, Southeast Asia, and

geners to the Russian North was made using a global

Central Asia and Africa.

emission inventory concerning 22 individual PCB con-

geners covering the period 1930-2000 (Breivik et al.,

The major emission sources of PCBs in the Northern

2002b). This inventory is based on estimates of the

Hemisphere in 1996 were the Americas (24%),

global production and consumption of these PCBs in

Russia (23%), Southeast Europe (19%), and

114 countries (Breivik et al., 2002a). The emissions

Northwest Europe (16%) (Figure 4.5(a)). The main

were distributed to the (2.5° x 2.5° lat./long.) model

Russian emission sources are located in Central-

grid using (as a proxy for emission distribution) a 1990

Chernozem, Volga and North-Caucasus regions (CVN)

population distribution data set obtained from the

as well as in Central and Volgo-Viatsky regions (CVV)

CGEIC website (http://www.ortech.ca/cgeic).

(Figure 4.5(b)).

The total global production of PCBs from 1930-1993

-HCH

amounted to approximately 1.3 million tonnes. Almost

The scenario for -HCH emissions in the Northern

97% of intentionally produced PCBs were used in the

Hemisphere was based on official data submitted to

Northern Hemisphere. Emission data for individual

the UN ECE Secretariat in 2002 (Vestreng and Klein,

congeners for 1996 were used in all model calculations

2000) and available expert estimates (Pacyna et al.,

and, according to the high emission scenario discussed

1999). In addition, -HCH emissions for 1990-1996

by Breivik et al. (2002b), total emissions of the 22 PCB

from the Russian Federation, and some other coun-

congeners in the Northern Hemisphere in 1996

tries in the Northern Hemisphere were estimated

amounted to about 662 tonnes. Total emissions of PCB-

from information in a range of literature sources

28, -118, -153, and -180 from the Northern Hemisphere

(Revich et al., 1999, Year-books, 1992, 1993 1999,

b

Figure 4.5.

(a) Contribution of different regions to PCB emissions (22 congeners)

in the Northern Hemisphere for 1996, (b) PCB emissions (22 congeners)

a

from different regions of the Russian Federation in 1996.

37

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

Chapter 4

b

Figure 4.6.

(a) Contribution of different regions to HCH emission

in the Northern Hemisphere for 1996, (b) HCH emissions

a

from different regions of the Russian Federation in 1996.

Ananieva et al., 1990, Li et al., 1996, 1998,1999, and

Mercury, PCB and -HCH concentrations in air and

Macdonald et al., 2000) regarding the use of this insec-

their deposition loads as evaluated for the Northern

ticide. To estimate emissions from data on insecticide

Hemisphere and the Arctic for 1996, are discussed

use, the emission factor for lindane in agricultural use

below in the relevant subsections. Particular attention

(0.5) (Guidebook, 1999) was applied. The resulting

has been given to atmospheric long-range transport to,

estimate for total -HCH emissions from the Northern

and deposition of these pollutants in the Russian

Hemisphere in 1996 was about 3445 tonnes. The spa-

Arctic. For mercury, the effect of Mercury Depletion

tial distribution of these -HCH emissions in the

Event (MDE) chemistry on Arctic deposition was con-

Northern Hemisphere, for modeling purposes, was

sidered. In addition, for the assessment of environ-

made using crop area as a surrogate parameter

mental pollution by PCBs and -HCH, the role of trans-

(Pacyna et al., 1999).

port via sea currents and ice cover dynamics were taken

into account. The marine environment is particularly

To model long-range atmospheric transport of -HCH

important in relation to the transport and fate of

to the Russian North, nine source regions were identi-

-HCH. Characteristic values of mean annual air con-

fied in the Northern Hemisphere: Russia, Western

centrations and deposition fluxes of mercury, PCBs

Europe, Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, the

and -HCH over the Arctic area are summarized in

Americas, China, India, the rest of Asia, and Africa.

Table 4.2. The consistency of the modeling results was

China and India were considered as individual source

verified by comparison with available measurements.

regions due to their high use of this insecticide com-

pared to the rest of Asia. Estimates of the contribution

of main source regions to total -HCH emissions in the

Northern Hemisphere in 1996, based on the selected

emission scenario, is shown in Figure 4.6(a). -HCH

emissions from Russian regions in 1996 are shown in

Figure 4.6(b).

The main contribution to -HCH emissions in the

Northern Hemisphere, was made by India (53%) and

Western Europe (18%). The contribution from

Table 4.2. Characteristic values of mean annual air concentrations and annual

Russia is only 2%. Major Russian -HCH emissions in

deposition fluxes for mercury, selected PCBs, and µ HCH over the Arctic in 1996.

1996 originated from the European part of the

Russian Federation. The highest Russian -HCH con-

Mercury

tributions were made by sources located in the

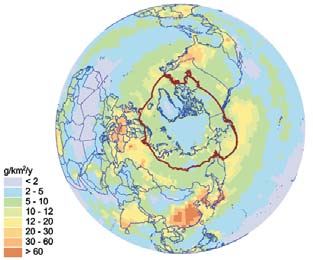

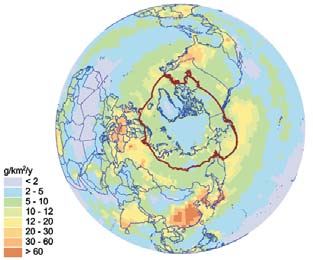

Figure 4.7 shows the annual deposition flux of mer-

Central-Chernozem, Volga and North-Caucasian

cury in the Northern Hemisphere. Highest deposi-

regions (CVN).

tion levels are in those regions with considerable

emissions: i.e. Southeast Asia, Europe, and the east-

4.2.3. Contamination levels in the Arctic resulting

ern part of North America. For other areas, the depo-

from long range atmospheric transport

sition pattern, to some extent, corresponds to annual

To evaluate levels of contamination of the Arctic region

precipitation values, since wet deposition plays a

by global pollutants (mercury, PCBs, and -HCH)

dominant role in removing mercury from the atmos-

resulting from long-range atmospheric transport, a

phere. From the model results, total deposition over

hemispheric modeling approach was employed. For

the Arctic region in 1996 amounted to 240 tonnes.

this purpose, the EMEP Meteorological Synthesizing

The influence of MDEs on deposition fluxes within

Centre-East (MSC-E) have developed hemispheric

the Arctic region has been the subject of considerable

multi-compartment transport models `MSCE-Hg-Hem'

research in recent years. The postulated MDE mecha-

and `MSCE-POP'.

nism (Lindberg et al., 2002) includes complicated

38

Chapter 4

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

chemistry, involving the formation of halogen related

Figure 4.7.

radicals. The development of a detailed model com-

Annual deposition

of total mercury in the

ponent for MDE chemistry is the subject of a separate

Northern Hemisphere.

study. For the purposes of this study, an attempt was

The enlarged panel shows

made to qualitatively estimate the effect of MDE on

elevated mercury deposition

over the Arctic coast due

Arctic Hg contamination by using a simplified set of

to MDEs.

parameters.

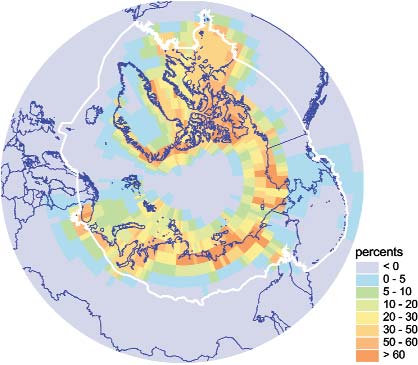

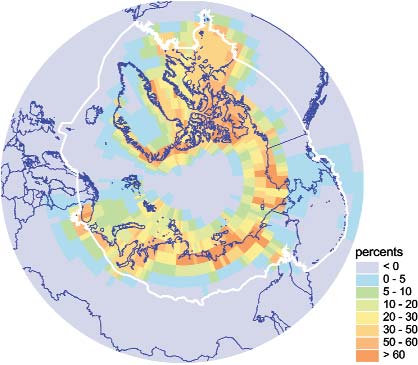

As illustrated in the enlarged panel in Figure 4.7, even

short-term phenomena such as MDEs, which occur

during only a few weeks of the year, can considerably

increase the annual deposition of mercury in some

regions of the Arctic, in particular coastal areas. The

influence of MDEs on total annual mercury deposition

is illustrated in Figure 4.8(a). Additional contributions

of mercury as a result of MDEs can amount to more

than 50 percent of total deposition values in areas adja-

cent to Arctic coasts (i.e. within about 300 km of the

coast inland and offshore). These areas include the

Queen Elizabeth Islands, Hudson Bay, the White Sea,

the Gulf of the Ob river, and the Laptev Sea coast,

among others. Negative values (for percentage

increase in deposition due to MDEs) show that

increased deposition fluxes due to MDEs in some

to the model parameters used), when monthly depo-

regions, lead to decreased fluxes in other areas. A part

sition in the Arctic increased two-fold or greater.

of the mercury transported by the air therefore does

The calculations predict that MDE are responsible

not enter the High Arctic during springtime, due to it

for deposition of about 50 tonnes of mercury per

being scavenged during MDEs over coastal and con-

year in the Arctic about 20% of the total annual

tiguous regions.

deposition.

Figure 4.8(b) shows the seasonal variation in total

Due to the high transport potential of mercury in the

mercury deposition in the Arctic. The model pre-

atmosphere, many anthropogenic and natural sources

dicts that the most pronounced MDE effect is in May

from different regions of the Northern Hemisphere

and June (taking into account a temporal shift due

contribute to Arctic pollution. The contribution from

Figure 4.8.

(a) Influence of MDEs on

total annual mercury deposi

tion in the Arctic (area

defined by the white (AMAP

area) boundary), and (b) sea

sonal variation in total mer

cury deposition to the Arctic

with and without MDEs. The

figures present the difference

between two model compu

tational runs one with and

one without MDEs included.

a

b

a

Figure 4.9. Contribution of different source regions to the annual deposition

of mercury in the Arctic arising from (a) anthropogenic sources and (b) natural

b

sources and re emissions.

39

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

Chapter 4

the various regions of the Northern Hemisphere to total

annual mercury deposition in the Arctic from anthro-

pogenic and from natural sources is shown in Figures

4.9(a) and 4.9(b), respectively for the upper (Scenario I)

and lower (Scenario II) limits of emission estimates.

Figure 4.10.

Mean annual air

concentrations of PCB 153

over the Northern

Hemisphere. The enlarged

panel shows the air

concentration pattern

over the Arctic region.

Figure 4.11.

Seasonal variation in the relative contributions of different source regions to PCB 153

deposition in the Arctic.

considerable uncertainty regarding the input parameters

used for the modeling of natural emission and re-emis-

sion processes, and that natural emissions cannot be con-

trolled by political decisions, attention should be focused

on deposition from anthropogenic sources.

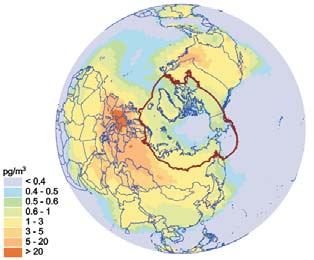

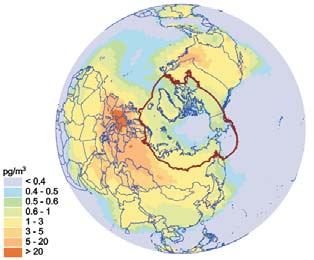

PCBs

Levels of PCB contamination are exemplified by PCB-

153. Figure 4.10 shows that areas with the highest air

concentrations of PCB-153 are located close to

European and North American source regions. Air

The most significant contribution to anthropogenic mer-

concentrations range from 5 to 20 pg/m3 in contami-

cury deposition in the Arctic come from sources located

nated areas of North America, and can exceed

in Southeast Asia, Europe and Russia. The most signifi-

20 pg/m3 in Europe. European sources make the

cant contributions to the natural component of annual

largest contribution to the contamination of the Arctic

deposition in the Arctic are from the Pacific and Atlantic

region. The mean annual air concentration of PCB-153

Oceans, and from Asia. Bearing in mind that there is still

over the Arctic ranges from 0.2 to 4 pg/m3.

Figure 4.12.

Air concentrations

of PCB 153 emitted in

January and May from

sources in the Americas

and Northwest Europe.

respectively, from modelling

results for 1996.

a

b

Americas

January

Northwest Europe

c

d

Americas

May

Northwest Europe

40

Chapter 4

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

The relative contributions made by different source

preceding 1996 equals 629 kg. Therefore, the esti-

regions to PCB-153 deposition in the Arctic are subject

mated total PCB-153 deposition to the Arctic in 1996

to seasonal variations, as shown in Figure 4.11. The

was 1.15 tonnes.

contribution from sources in Northwest Europe is the

most variable, varying from about 70% in January, to

On the basis of the transport simulations for the four

about 25% in May. The amount contributed by the

congeners (PCB-28, -118, -153, and -180), and taking

Americas is only about 5% in January, but in May it

into account the fractions of these congeners in the

amounts to 26%, and is comparable with the contribu-

typical PCB mixture in air, a rough estimate of total

tion from sources in Northwest Europe.

PCB deposition in the Arctic in 1996 of approximately

40 tonnes was made.

These noticeable variations are explained by the

peculiarities of atmospheric circulation in the Arctic

-HCH

during various seasons, and also by seasonal varia-

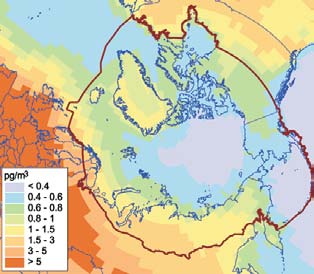

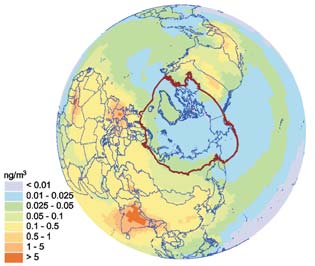

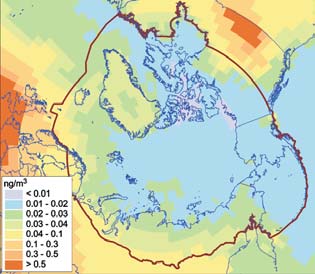

Figure 4.14 represents the spatial distribution of -

tions in temperature, precipitation, and degradation

HCH concentrations in the air over the Northern

rates. Seasonal variation of emissions are not taken

Hemisphere and the Arctic. High concentrations (up

into account in this assessment. To illustrate pathways

to 5 ng/m3 or more) are mainly characteristic of

of atmospheric transport, simulation results of regions with high emissions. However, in spite of the

PCB-153 transport from two source regions (the

fact that there are no significant sources in the Arctic

Americas and Northwest Europe) for 1996 were

region, relatively high concentrations (from 0.01 to

examined. Figures. 4.12 show air concentrations of

0.11 ng/m3) are also observed there. These concentra-

PCB-153 emitted in the Americas and Northwestern

tions result from long-range transport of -HCH from

Europe in January. The air concentrations of PCB-

remote sources, mainly in Western Europe, India, and

153 originating from the same sources in May are

the Americas.

given in Figures. 4.12.

Figure 4.13 shows the contribution of different source

regions to PCB-153 deposition in the Arctic. The major

contribution is from sources in Northwest Europe

(about 40%). Other significant contributors are Russia

(19%), the Americas (17%) and Southeast Europe

(16%). For PCB-28 and PCB-118, Northwest Europe

and Russia are the main contributors. However, for

PCB-180, main contributors are Northwest Europe and

the Americas.

The total amount of PCB-153 deposited in the Arctic

region from emissions in 1996 was estimated at

527 kg. The contribution from re-emission of PCB-

Figure 4.13. Contributions of different source regions to PCB 153

153 accumulated in the environment in the period

deposition in the Arctic region in 1996.

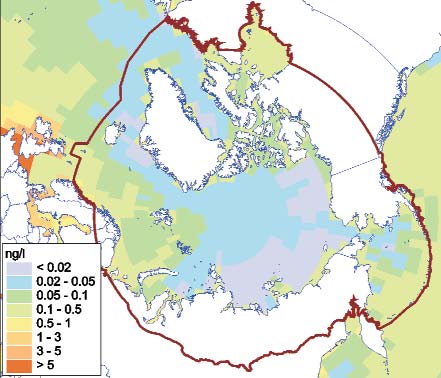

Figure 4.14.

Figure 4.15.

HCH concentrations

Mean annual concentrations

in air of the lower

of HCH in seawater

atmosphere over

in the Northern Hemisphere.

the Northern Hemisphere

The enlarged panel shows

and the Arctic.

the seawater concentrations

pattern over the Arctic

Ocean.

41

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

Chapter 4

Since -HCH tends to accumulate in seawater (which

accounts for about 80% of the overall environmental

pool of this substance), the spatial distribution of -

HCH in seawater is of interest. The distribution of -

HCH in seawater (Figure 4.15) reveals that maximum

concentrations are found in the Indian Ocean, the

Mediterranean Sea, and the East Atlantic.

Considerable amounts of -HCH flow into the Arctic

Ocean from the North Atlantic, as reflected in the

higher seawater concentrations in the Barents Sea in

the region between northern Norway and Svalbard.

Seawater concentrations in the seas along the coast of

northern Russian are in the range 0.012 ng/L.

Figure 4.17. Spatial distribution of mean annual air concentrations

of total gaseous mercury in the Russian North.

The total amount of -HCH deposited in the Arctic

region in 1996 from the atmosphere was estimated to

regions including the Yamalo-Nenets AO, the Republic

be 78 tonnes. Due to high deposition rates over the sea

of Sakha (Yakutia), and the Chukchi AO. A possible

(the models assume this rate to be twice as high over

reason for this, in addition to distance from main emis-

sea as on land), and taking into account the large pro-

sions areas, is the decrease in elemental mercury con-

portion of the Arctic area that is covered by ocean

centration over the Arctic coast during springtime, as a

(about 60%, according to figures provided by AMAP,

result of MDEs.

1998), this equates to an estimate for -HCH deposited

Table 4.3.

to the Arctic Ocean in 1996 of 58 tonnes.

Characteristic values of mer

cury air concentrations in the

Modeling results have been used to indicate contribu-

Russian North, ng/m3.

tions of different emission sources to the contamina-

tion of the Arctic region by -HCH (Figure 4.16).

Western Europe is the largest contributor to this region

(about 40%), followed by India (19%), the Americas

(17%), China (10%), and Russia (6%), with other

source regions responsible for the remaining 8%.

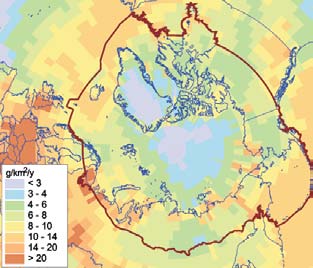

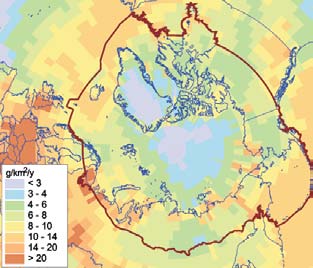

The spatial distribution of annual deposition loads of

total mercury in the Russian North is shown in Figure

4.18. The highest depositions, exceeding 20 g/km2/y,

are observed over the coast of the Arctic Ocean, due to

MDEs (Table 4.4). The lowest depositions (less than

5 g/km2/y), are in Central Yakutia, an area of low

annual precipitation. Values of total mercury deposi-

tion for regions of the Russian North and the Arctic as

a whole are given in Table 4.5.

Figure 4.16. Contributions of different source regions to HCH deposition

in the Arctic in 1996.

4.2.4. Contamination levels and deposition loads

resulting from long range atmospheric transport

to the Russian North

Mercury

Figure 4.17 shows the modeled spatial distribution of

Figure 4.18. Annual deposition of total mercury

mean annual concentrations of total gaseous mercury

in the Russian North.

(TGM) in the air in northern Russia, which are fairly

Table 4.4.

constant across the territory (from 1.4 to 1.8 ng/m3)

Characteristic values of total

(see also Table 4.3). Concentration levels over

annual mercury deposition

Murmansk Oblast and in the central Republic of Sakha

loads in the Russian North,

g/km2/y.

(Yakutia) are slightly elevated, mainly due to local

emission sources. There is also a weak decreasing gra-

dient in mercury concentrations to the north over

42

Chapter 4

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

A similar pattern is seen for deposition loads.

Substantial values (>150 mg/km2/y) are estimated for

Murmansk Oblast, the Nenets AO and the southern

part of the Yamalo-Nenets and Taymir AOs as well as for

Table 4.5. Total deposition of mercury in 1996 in different regions

the western part of the Sakha Republic. Moderate val-

of the Russian North, and the Arctic as a whole, t/y.

ues (70-150 mg/km2/y) are obtained for the northern

part of the Yamalo-Nenets and Taymir AOs, the

PCBs

Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), and the western part of

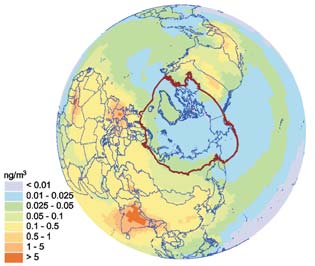

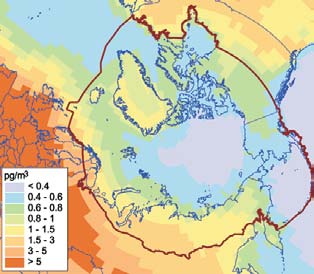

Figures 4.19 and 4.20 show the spatial distributions of

Chukchi AO. The northern parts of the Russian North

mean annual air concentrations and annual deposition

are characterized by lower values for deposition loads

loads of PCB-153 over selected regions of the Russian

(<70 mg/km2/y) (Table 4.7).

North for 1996. There is a clear decrease in PCB-153

Table 4.7.

air concentrations from western to eastern areas of the

Characteristic values

Russian North, with increasing distance from source

of PCB 153 annual deposition

areas in Europe. Relatively high air concentrations (up

loads in the Russian North,

mg/km2/y.

to 4 pg/m3) occur in Murmansk Oblast, the Nenets

AO, and the southern part of the Yamalo-Nenets and

Taymir AOs (Table 4.6). Moderate values (12 pg/m3)

are characteristic of the northern part of the Yamalo-

Nenets AO, the Taymir AO, and the Republic of Sakha

(Yakutia). The Chukchi AO is characterized by low val-

Depositions of PCB-153 and of total PCBs to the

ues (<1 pg/m3).

Russian North and the Arctic are given in Table 4.8. To

calculate these depositions, emissions of the 22 PCB

congeners considered, from all source regions, were

divided into four groups: di- plus tri-chlorinated PCBs,

tetra- plus penta-chlorinated PCBs, hexachlorinated

PCBs, and hepta- plus octa-chlorinated PCBs. It was

assumed that these groups are transported in a similar

way to PCB-28, -118, -153 and -180, respectively.

Together, these 22 congeners represent about one half

of total PCB emissions, a fact that was taken into

account in the calculation.

Figure 4.19. Spatial distribution of mean annual air concentrations

of PCB 153 in the Russian North, calculated for 1996.

Table 4.8. Total deposition of PCB 153 and total PCB in 1996

Table 4.6.

in different regions of the Russian North, and the Arctic as a whole, t/y.

Characteristic values

of PCB 153 air concentrations

in the Russian North, pg/m3.

By undertaking simulations of long-range transport

and the accumulation of four PCB congeners (PCB-28,

-118, -153 and -180), it was possible to compare the con-

gener compositions in the air of different regions of

the Russian North (Figure 4.21).

Figure 4.21.

PCB congener composition

in air of different regions

of the Russian North.

For all receptor regions, the fraction of PCB-28 is the

highest and PCB-180 the lowest, with other congeners

Figure 4.20. Annual deposition of PCB 153 in the Russian North,

falling between, however, the congener patterns vary

calculated for 1996.

noticeably between the regions.

43

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

Chapter 4

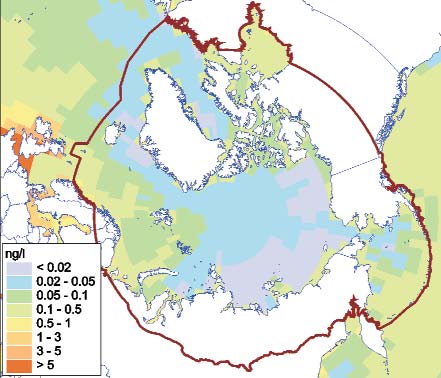

-HCH

lower for the Taymir AO, the Republic of Sakha

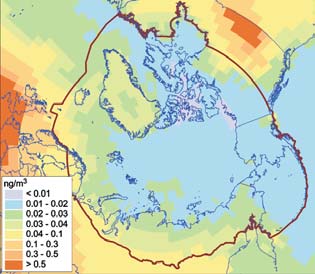

Mean annual air concentrations of -HCH in the recep-

(Yakutia), and the Chukchi AO (0.13 g/km2/y).

tor regions of the Russian North, for 1996, are illustrat-

Annual deposition loads vary from region to region

ed in Figure 4.22. Higher air concentration levels (from

(Table 4.10). This is mainly due to different precipita-

0.02 to 0.07 ng/m3) are characteristic for Murmansk

tion levels in these regions.

Oblast, the Nenets AO, the south of the Yamalo-Nenets

AO, and the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Lower levels

Estimated values for total deposition of -HCH in the

(from 0.01 to 0.3 ng/m3) are characteristic for the

regions of the Russian North and the Arctic as a whole

Taymir AO, the Chukchi AO, and the north of the

are given in Table 4.11.

Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) (Table 4.9).

Table 4.11. Total deposition of HCH in 1996 in different regions of the Russian

North, and the Arctic as a whole, t/y.

4.2.5. Source receptor relationships

for the selected pilot study regions.

4.2.5.1. Murmansk Oblast

Mercury

Murmansk Oblast is the most westerly region of

Russia and is located on the Kola Peninsula. This

Figure 4.22. Spatial distribution of mean annual air concentrations of

explains the greater influence of European sources

HCH

in the Russian North, calculated for 1996.

of mercury on this region (including sources both

inside and outside the territories of Russia). Figures

Table 4.9.

4.24(a) and 4.24(b) illustrate the contributions of

Characteristic values

of HCH air concentrations

major Northern Hemispheric and Russian anthro-

in the Russian North, ng/m3.

pogenic mercury source regions to annual mercury

deposition in Murmansk Oblast. The largest contri-

bution is made by Russian sources (35%). Among

these, about 13% is from Murmansk Oblast itself

(MUR) and 18% from other Russian European

regions (NRT, NWK, CVV, CVN and URL). The most

The spatial distribution of -HCH annual deposition

important sources outside of Russia are those in

loads is shown in Figure 4.23. Deposition loads are larg-

Eastern Europe (12%), China (11%), the Americas

er for Murmansk Oblast, the Nenets AO, and the

(10%), and Western Europe (10%). The `other' cate-

Yamalo-Nenets AO (from 2 to 7 g/km2/y or more) and

gory (defined in this and other sections addressing

mercury source-receptor relationships) includes

Northern and Southern Europe, Southeast Asia

(excluding China and Japan), and Africa, due to

their relatively small contributions to depositions in

the receptor area.

PCB

The largest contributions to PCB-153 deposition in

Murmansk Oblast are from emission sources in

Russia (44%), Northwest Europe (35%) and

Southeast Europe (14%) (Figure 4.25(a)). Contri-

butions from sources located in the Americas, Africa,

and Central Asia are less significant due to their con-

Figure 4.23. Annual deposition of

siderable distance from the Oblast. Amongst Russian

HCH in the Russian North,

calculated for 1996.

sources (Figure 4.25(b)), the major contribution is

made by emissions from Murmansk Oblast itself

Table 4.10.

(22%).

Characteristic values of HCH

annual deposition loads in the

Russian North, g/km2/y.

-HCH

-HCH sources in Western Europe make the largest

contribution to deposition in Murmansk Oblast (more

than 50%). Other significant contributors are Russia

(17 %) and India (9%) (Figure 4.26(a)).

44

Chapter 4

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

b

Figure 4.24. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual mercury deposition

a

in Murmansk Oblast.

b

Figure 4.25. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual PCB 153 deposition

a

in Murmansk Oblast.

b

Figure 4.26. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, and (b) regions of Russia to annual HCH deposition

a

in Murmansk Oblast.

Russian contributions to -HCH depositions in

4.2.5.2. The Nenets Autonomous Okrug

Murmansk Oblast are mostly made by the Central and

Volgo-Viatsky regions (CVV) and the Central-

Mercury

Chernozem, Volga, and North-Caucasian regions

The Nenets AO is located in the northern part of

(CVN), 5% and 4%, respectively. The inputs from

European Russia. Therefore the main source areas of

other regions are comparatively small (Figure 4.26(b)).

long-range atmospherically transported pollution

For the purposes of this report, contributions from

affecting the region are similar to those affecting

Russian emission sources to -HCH depositions in

Murmansk Oblast. Differences in deposition are asso-

receptor areas are shown only for those regions with

ciated mainly with the greater significance of Russian

significant emissions of -HCH.

emission source regions. Figures 4.27(a) and 4.27(b)

b

Figure 4.27. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions of the

a

Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual mercury deposition in the

Nenets AO.

45

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

Chapter 4

show the relative contribution of the different regions

-HCH

to the total annual deposition of mercury in the Nenets

The major contributions to the contamination of the

AO from anthropogenic sources. The largest contribu-

Nenets AO by -HCH are from emission sources in

tion is from Russian sources (35%). However, sources

Western Europe (49%), Russia (23%), and India (9%)

within the Nenets AO itself only contribute 7%, where-

(Figure 4.29(a)). The main sources within the Russian

as the combined contribution of regions in European

Federation are the Central and Volgo-Viatsky regions

Russia make up 24% of the deposition. The most

(CVV) and the Central-Chernozem, Volga, and North-

important of these are the Northern region (NRT) and

Caucasian regions (CNV), contributing 8% each

the Central and Volgo-Viatsky regions (CVV). The most

(Figure. 4.29(b)).

significant external contributors are Eastern Europe

(13%), China (11%), the Americas (10%), Western

4.2.5.3. The Yamalo Nenets and Taymir Autonomous Okrugs

Europe (9%), and Central Asia (9%).

Mercury

PCB

The location of the Yamalo-Nenets AO and the Taymir

The largest contributions to PCB-153 depositions are

AO in the northern part of western Siberia, accounts

made by Russia (41%), Northwest Europe (31%) and

for the fact that Asian sources play a noticeable role in

Southeast Europe (18%) (Figure 4.28(a)). The main

their contamination. European sources, however, still

contributions among Russian sources (Figure 4.28(b))

continue to exert a considerable influence. Up to 30%

are made by the Central and Volgo-Viatsky regions

of all mercury annually deposited in these two regions

(CVV) and the Northern region (NRT), with values of

is from Russian sources (Figure 4.30(a)). The contri-

15% and 10%, respectively.

bution from sources within the Yamalo-Nenets and

b

Figure 4.28. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual PCB 153 deposition

a

in the Nenets AO.

b

Figure 4.29. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual HCH deposition

a

in the Nenets AO.

b

Figure 4.30. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual mercury deposition

a

in the Yamalo Nenets AO and the Taymir AO.

46

Chapter 4

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

b

Figure 4.31. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual PCB 153 deposition

a

in the Yamalo Nenets AO and the Taymir AO.

b

Figure 4.32. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual HCH deposition

a

in the Yamalo Nenets AO and the Taymir AO.

b

Figure 4.33. Contributions from anthropogenic sources

in (a) regions of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia

a

to annual mercury deposition in the Chukchi AO.

Taymir AOs themselves is comparatively low (only

10% (Figure 4.32(a)). Russian contributions to deposi-

about 3%), whereas three major Russian contributors

tions in the Yamalo-Nenets and Taymir AOs are mainly

(CVV, CVN, and URL) make up 16% of total deposi-

from the Central and Volga-Viatsky regions (CVV) and

tion (Figure 4.30(b)). The two major external contrib-

the Central-Chernozem, Volga, and North-Caucasian

utors are China (12%) and Eastern Europe (12%).

regions (CVN), 7% and 8% respectively (Figure 4.32(b)).

Some impact is also made by the Americas (11%),

Central Asia (11%) and Western Europe (9%).

4.2.5.4. Chukchi Autonomous Okrug

Mercury

PCB

The Chukchi AO is the most eastern and remote region

Major contributions to PCB deposition in the Yamalo-

of the Russian North. Its location, far from major indus-

Nenets and Taymir AOs are made by sources in Russia

trial regions, accounts for the fact that the global back-

(47%), Northwest Europe (26%) and Southeast Europe

ground pool of atmospheric mercury is the main source

(16%) (Figure 4.31(a)). Among Russian sources (Figure

of mercury contamination in this region. Figure 4.33(a)

4.31(b)), the largest contribution (12%) to depositions

demonstrates the relative contributions of different

are made by the Central and Volgo-Viatsky regions

source regions to annual mercury deposition in the

CVV). The contribution of emission sources located

Chukchi AO. The main contributor is Russia (26%),

within the Yamalo-Nenets and Taymir AOs is 9%.

however, contributions from China are also consider-

able (17%). Among other sources, the Americas (11%),

-HCH

Central Asia (10%), and Eastern Europe (10%) are of

Main contributors to depositions of -HCH in the

note. The contribution from the Chukotka AO itself is

Yamalo-Nenets and Taymir AOs are similar to those for

insignificant compared to emission sources located in

the Nenets AO. Sources in Western Europe make the

Eastern Siberia and the Far East (Figure 4.33(b)).

largest contribution to ongoing deposition in these terri-

However, the influence of major emission regions in

tories (48%). Russia is responsible for 21% and India, for

European Russia (CVV, CVN, URL) are also apparent.

47

4.2. Assessment of distant sources: Long range atmospheric transport

Chapter 4

b

Figure 4.34. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual PCB 153 deposition

a

in the Chukchi AO.

b

Figure 4.35. Contributions from anthropogenic sources in (a) regions

of the Northern Hemisphere, (b) regions of Russia to annual HCH deposition

a

in the Chukchi AO.

PCB

Main contributions to -HCH deposition are made by

The most important contributions to PCB-153 depo-

sources within Western Europe (54%), Russia (17%),

sition in the Chukchi AO are made by sources locat-

and India (9%). Russian contributions to deposition

ed in Russia (25%), Northwest Europe (22%), and

are mainly from sources located in the Central and

Southeast Europe (19%), followed by American

Volgo-Viatsky regions (5%), and Central-Chernozem,

sources (17%). (Figure 4.34(a)). The main contribu-

Volga, and North-Caucasian regions (4%). Total annu-

tion from the Russian source regions (Figure

al deposition of -HCH amounts to 0.8 t.

4.34(b)) is made by emissions from the Chukchi

AO itself (8%).

The Nenets Autonomous Okrug

The most important contribution to anthropogenic

-HCH

mercury depositions in the Nenets AO is made by

For the Chukchi AO, the main contributions to -HCH

Russian emission sources (35%). As well as deposition

contamination are made by India (27%), Western

from sources within the Nenets AO itself (7%), emis-

Europe (27%), China (19%), and the Americas (11%)

sions from regions in the European part of Russia con-

(Figure 4.35(a)). The contribution from all Russian

tribute considerably to the pollution of this region

sources accounts for only 5% (Figure 4.35(b)).

(24%). The most important external contributors are

Eastern Europe (13%), China (11%), and the

4.2.6. Conclusions

Americas (10%). Total annual deposition of mercury in

Murmansk Oblast

the Nenets AO amounts to 4 t, of which 1.8 t is from

The largest contribution to anthropogenic mercury

anthropogenic sources.

deposition in the Oblast is made by Russian sources

(35%) of which 13% is from sources within Murmansk

Main contributions to PCB deposition in the Nenets

Oblast itself. The most important external sources are

AO are from sources in Russia (41%), Northwest

Eastern Europe (12%), China (11%), the Americas

Europe (31%), and Southeast Europe (18%). Major

(10%), and Western Europe (10%). Total annual depo-

contributions from sources within the Russian

sition of mercury is around 3 t, including 1.5 t from

Federation are made by the Central and Volgo-Viatsky

anthropogenic sources.

regions (15%), and the Northern region (10%). The

contribution of local sources to deposition in the

A major contribution to PCB deposition is made by

Nenets AO is negligible. Total annual deposition of

Russian sources (44%) including 22% from sources

PCB-153 in this Okrug amounts to 31 kg, and of total

within Murmansk Oblast itself. Among other emission

PCBs, 1 t.

sources, significant contributions originate in

Northwest Europe (35%), and Southeast Europe

-HCH pollution of the Nenets AO is due to emission

(14%). Total annual deposition of PCB-153 in

sources in Western Europe (49%), Russia (23%), and

Murmansk Oblast amounts to 20 kg, and of total

India (9%). The main sources within the Russian

PCBs, 0.7 t.

Federation are the Central and Volgo-Viatsky regions

48

Chapter 4

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

(8%), and the Central-Chernozem, Volga, and North-

In addition, the following general conclusions can be

Caucasian regions (8%). Total annual deposition of made, based on the studies undertaken:

-HCH to this Okrug is 1.1 t.

·

Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia are the

most significant emission source regions for mer-

The Yamalo-Nenets

cury, PCBs and -HCH. The main Russian emission

and Taymir Autonomous Okrugs

sources are located in the European part of the

The major contribution to anthropogenic mercury

Russian Federation. Due to their geographical

deposition in these regions is from emissions sources

location, and to meteorological conditions,

in Russia (30%). Among Russian sources, the main

European sources make the greatest contribution

contributors are sources in the Ural, Central and

to the contamination of the western regions of the

Volgo-Viatsky regions, and the Central-Chernozem,

Russian North. Asian and North American sources

Volga, and North-Caucasian regions (16% in total).

play a more significant role in the pollution of the

Main external contributors are China (12%), Eastern

eastern territories of the Russian Arctic, although

Europe (12%), the Americas (11%), and Central Asia

the contribution of European sources is still con-

(11%). Total annual deposition of mercury is estimat-

siderable.

ed at 15 t, of which 6.6 t is from anthropogenic

sources.

·

The results obtained make it possible to make some

predictions for the near future regarding contami-

Major contributions to PCB depositions are made by

nation levels in the Russian Arctic. An analysis of

sources located in Russia (47%), Northwest Europe

emission data shows that mercury emissions are

(26%) and Southeast Europe (16%). Among Russian

decreasing in Europe and North America, whereas

sources, the largest contribution to deposition is made

emissions from Southeast Asia are increasing. Asian

by the Central and Volgo-Viatsky regions (12%). Total

sources may eventually become the more signifi-

annual deposition of PCB-153 is 95 kg, and 3.2 t for

cant, thus contamination levels of this pollutant in

total PCBs.

some regions of the Russian North, in particular the

Chukchi AO, may increase in the future. Regarding

Main contributions to -HCH depositions are made by

-HCH, use of technical-HCH (a mixture of HCH

Western Europe (48%), Russia (21%), and India

isomers, including -HCH) is now banned in most

(10%). Main sources within the Russian Federation are

western countries, and in Russia since the late-

the Central and Volgo-Viatsky regions (7%) and the

1980s; China, a major user, also switched to lindane

Central-Chernozem, Volga, and North-Caucasian

(pure -HCH) in 1984. Although restricted in most

regions (8%). Total annual deposition of -HCH

countries, lindane is still widely used in North

amounts to 4 t.

America, Europe and Asia, for seed treatment and

other applications (AMAP, 2002). Thus the relative

The Chukchi Autonomous Okrug

influence of Asian countries on pollution of the

The main contributions to anthropogenic mercury

Russian Arctic by -HCH is likely to increase. PCB

deposition in this Okrug originate from Russian

contamination levels are expected to decrease with

sources (26%). Emission sources from Eastern Siberia

emission reductions resulting from bans and con-

and the Far East are the dominant influences on mer-

trols on use of PCBs. However PCB contamination

cury contamination of the Chukchi AO. The main

is likely to continue for many years as a result of re-

external contributor to the region's pollution is China

emissions from PCBs accumulated in the general

(17%), with a contribution comparable to that of

environment over the last 50-years.

Russian sources, although this varies slightly during

the year. Among others, the Americas contribute 11%

and Central Asia 10% to the deposition. Total annual

4.3. Preliminary assessment

deposition of mercury is estimated at 7 t, of which 2.9 t

of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

is from anthropogenic sources.

4.3.1. Introduction

The main contributors to PCB deposition are the fol-

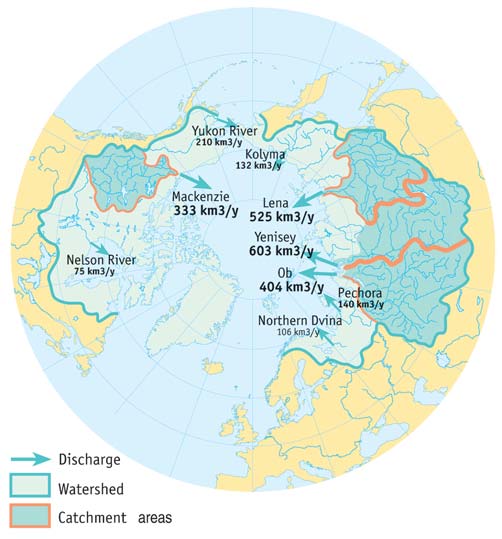

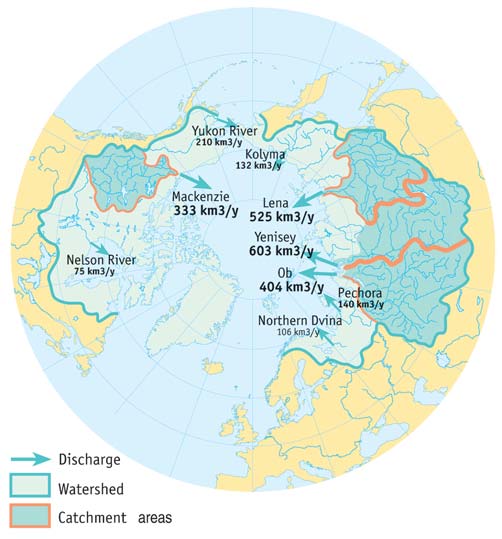

Flows of large Arctic rivers are considered one of the

lowing: Russia (25%), Northwest Europe (22%), and

most significant pathways by which contaminants reach

Southeast Europe (19%), followed by American

the Arctic. Riverine transport is particularly relevant

sources (17%). The Chukchi AO itself contributes 8%.

for PTS, as potentially PTS contamination within the

The total annual deposition of PCB-153 amounts to

entire catchment areas of these rivers can be transport-

11.8 kg, and of total PCBs, 0.4 t.

ed to the Arctic through watershed runoff, and these

catchments include heavily industrialized areas and

Main contributions to -HCH deposition are made

agricultural regions (Figure 4.36).

by India (27%), Western Europe (27%), China

(19%), and the Americas (11%). The contribution

Riverine PTS transport is particularly important for

from Russian sources accounts for 5%. Total annual

two of the study areas selected for project implementa-

deposition of -HCH in the Chukchi AO is estimated

tion: the lower Pechora basin, and the eastern part of

at 1.4 t.

the Taymir Peninsula, in the area of the Yenisey river.

49

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Chapter 4

Yenisey basin, are heavily industrialized. Industrial

enterprises within these areas include non-ferrous met-

allurgy, pulp and paper manufacture, chemical indus-

tries, and mining, etc., which are recognized as signifi-

cant sources of PTS emissions and discharges.

The catchment area of the Pechora river comprises

0.325 million km2 (world ranking 46), with a mean

long-term annual runoff of 141 km3 (world ranking:

30). The Pechora river basin, including the catchments

of its primary and secondary tributaries the Vorkuta,

Bol'shaya Inta, Kolva, Izhma and Ukhta rivers, contain

areas rich in mineral resources, with associated oil, gas

and coal extraction activities.

4.3.2. Objectives and methodology of the study

The objective of this study was to estimate PTS fluxes in

the flows of the Pechora and Yenisey rivers to areas

inhabited by indigenous peoples. Calculations of PTS

loads in the lower reaches of the Pechora and Yenisey

rivers used a range of data, included hydrometric meas-

urements at the closing cross-sections of the

Roshydromet basic hydrological network (in the area of

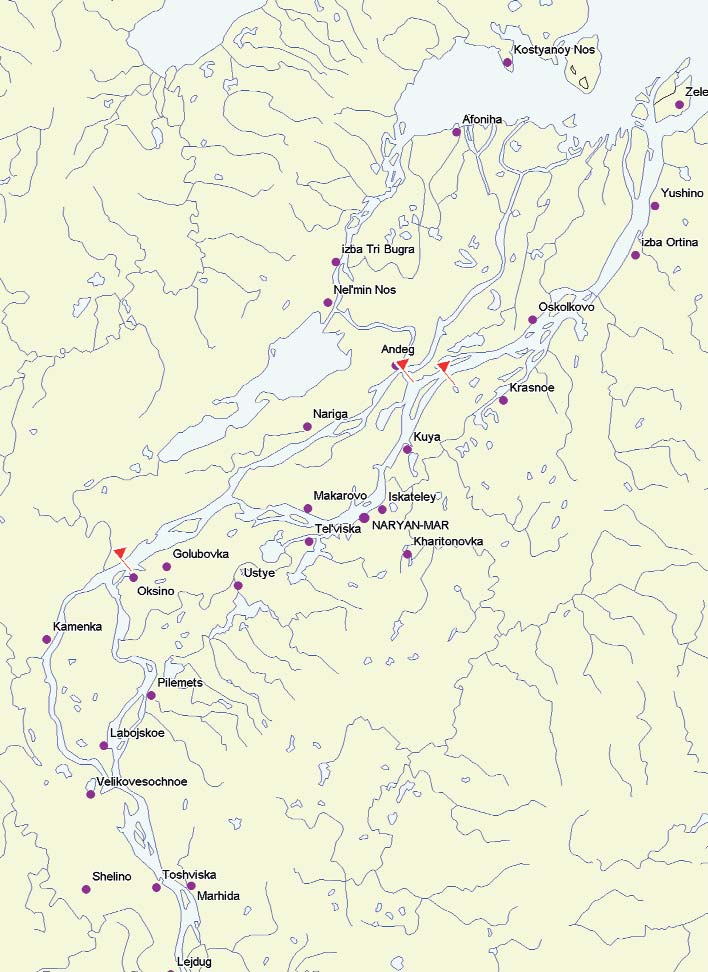

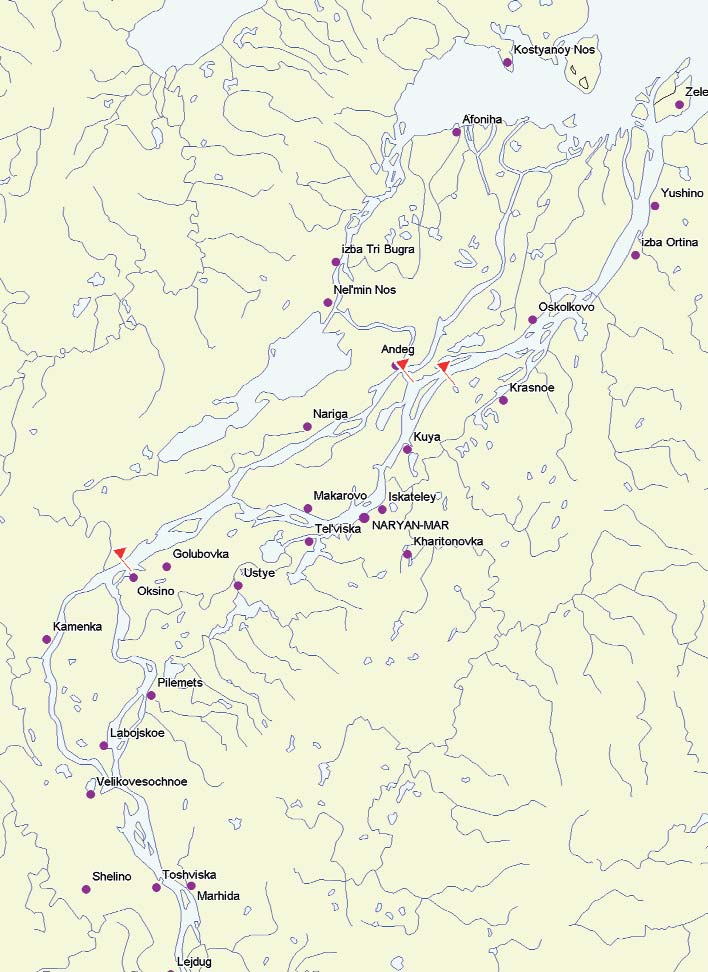

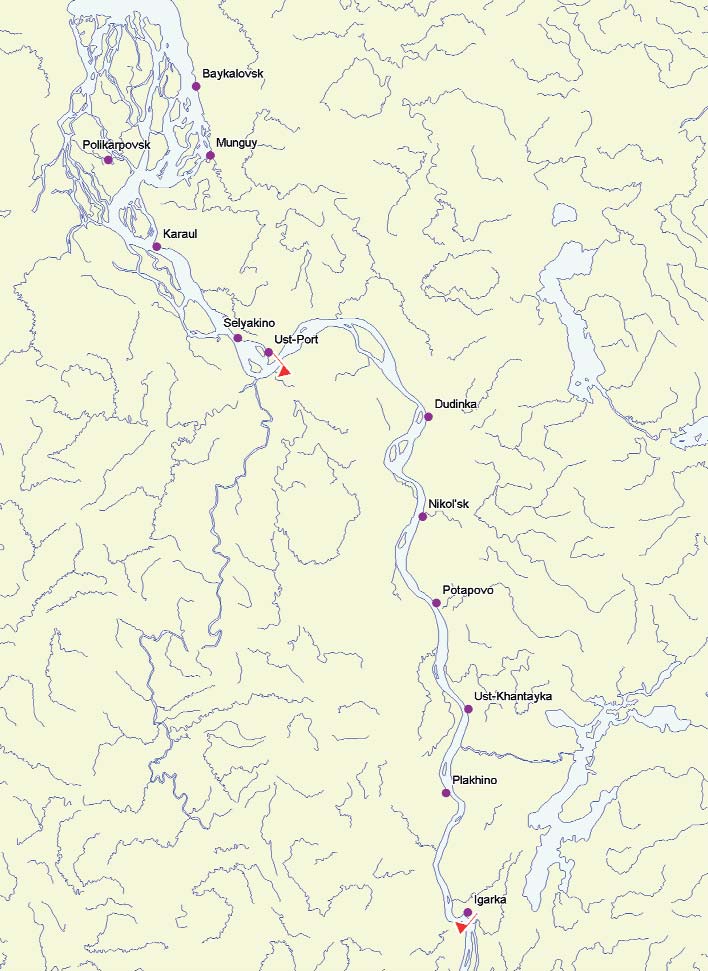

Figure 4.36. Arctic Ocean watershed, and catchment areas

Oksino settlement on the Pechora River and Igarka set-

of the largest Arctic rivers (AMAP, 1998).

tlement on the Yenisey River), and at the lowermost

cross-sections in the delta apexes, upstream of the rivers'

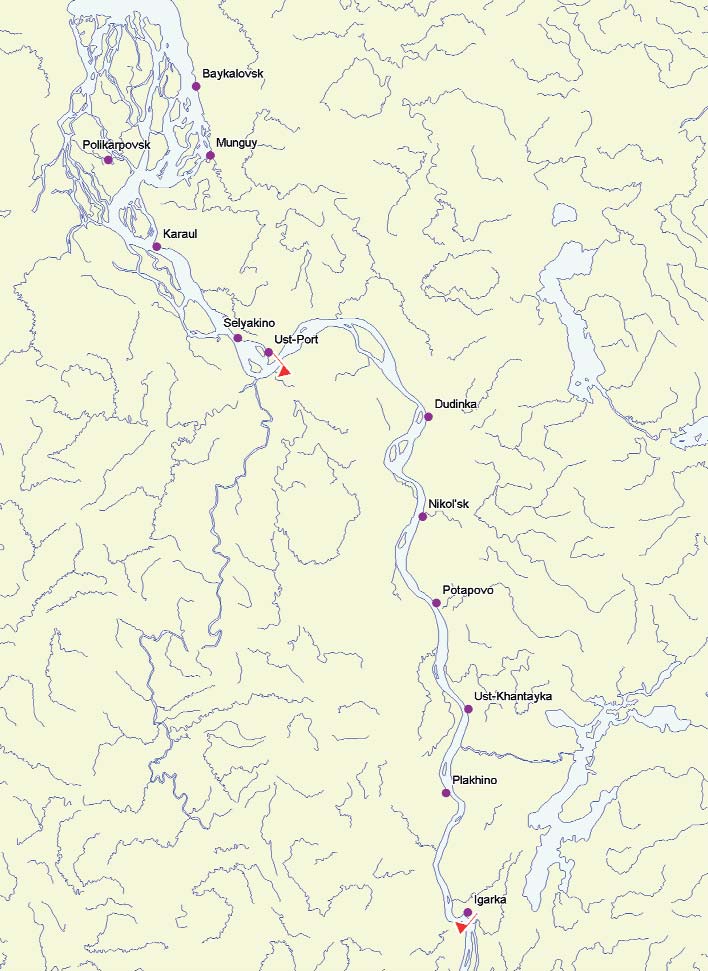

The Yenisey is one of the world's ten largest rivers, with

main branching points (in the vicinity of Andeg settle-

a catchment area of 2.59 million km2 (world ranking: 7)

ment, on both the Large and Small Pechora rivers, and

and mean long-term annual runoff of 603 km3 (world

of Ust'-Port settlement, on the Yenisey River) (Figures

ranking 5) (GRDC, 1994). Its basin incorporates the

4.37 and 4.38). In addition, data were obtained from

East-Siberian economic region, parts of which, particu-

analysis of pooled water and suspended matter samples

larly those located in the upper and central parts of the

collected during periods of hydrological observations.

Figure 4.37. Location of hydrometric cross sections on the Pechora river.

Figure 4.38. Location of hydrometric cross sections on the Yenisey river.

50

Chapter 4

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Hydrometric measurements and water sampling at

each of the cross-sections were carried out according to

internationally accepted methodologies (GEMS, 1991;

Chapman, 1996) during four typical hydrological

water regime phases: during the spring flood fall peri-

od (late-June to early-July), during the summer low

water period (late-July to early-August), before ice for-

mation during the period of rain-fed floods (late-

September to October), and during the winter low

water period (March to April).

During each field survey period, measurements of

flow velocity at various sampling points in the channel

Figure 4.39. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points

profile were made every 6 hours, for 3 days. Water

on the Large Pechora river at the closing cross section near Oksino settlement.

level observations were conducted every 2 hours.

Water sampling was carried out twice during the first

observation day and once a day during the next two

days (a total of 4 single samples for each sampling

point). The volume of each pooled sample was not less

than 20 litres.

Initial data for each water regime phase included:

·

For the Pechora river at the closing cross-section

near Oksino settlement (see Figure 4.39):

15 flow velocity measurements (3 horizontal lev-

els on each of 5 vertical profiles );

measurement of the channel profile;

Figure 4.40. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points on the Large

36 measurements of the river water level;

Pechora river at the downstream cross section near Andeg settlement.

analytical data on PTS concentrations in 11

pooled water and 11 pooled suspended matter

samples collected over a 3-day period in 11 cross-

section segments;

suspended matter concentrations for samples

taken at the flow velocity measurement points,

in 11 pooled water samples, collected over a

3-day period in 11 cross-section segments.

·

For the Large and Small Pechora rivers at the down-

stream cross-sections near Andeg settlement (see

Figures 4.40 and 4.41):

Figure 4.41. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points on the Small

12 flow velocity measurements (3 horizontal lev-

Pechora river at the downstream cross section near Andeg settlement.

els on each of 4 vertical profiles, in both rivers);

measurement of the channel profile;

36 measurements of the river water level;

analytical data on PTS concentrations in 3

pooled water samples and 3 pooled suspended

matter samples from the surface, middle and

near-bottom horizons collected over a 3-day

period;

suspended matter concentrations in 3 pooled

water samples collected over a 3-day period from

the surface, middle and near-bottom horizons.

Figure 4.42. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points on the Yenisey

·

For the Yenisey river at the closing cross-section

river at the closing cross section near Igarka settlement.

near Igarka settlement (see Figure 4.42):

15 flow velocity measurements (3 horizontal lev-

matter samples collected over a 3-day period in

els on each of 5 vertical profiles);

11 cross-section segments;

measurement of the channel profile;

suspended matter concentrations for the flow

36 measurements of the river water level;

velocity measurement points in 11 pooled water

analytical data on PTS concentrations in 11

samples, collected over a 3-day period from 11

pooled water samples and 11 pooled suspended

cross-section segments.

51

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Chapter 4

4. calculation of partial and total mean daily fluxes of

PTS in dissolved form during the typical water

regime phases;

5. calculation of partial and total mean daily fluxes of

PTS in suspended matter during the typical water

regime phases.

The river channel profiles used in the hydrometric

measurement cross-sections were evaluated on the

basis of depth measurements and water level observa-

tions. Depth measurements (at various points across

Figure 4.43. Channel profile and sampling/measurement points on the Yenisey

the channel) were taken once, prior to the start of the

river at the downstream cross section near Ust' Port.

3-day observation period. Water level observations

were then made every two hours for three days. To

·

For the Yenisey river at the downstream cross-sec-

model the channel profile, an averaged single value

tion near Ust'-Port settlement (see Figure 4.43):

for water level above the original gauging station

15 flow velocity measurements (3 horizontal lev-

datum was applied across the river cross section.

els on each of 5 vertical profiles);

Thus, 16 profiles were evaluated (one for each of the

measurement of the channel profile;

four cross-sections in each of the four water regime

36 measurements of the river water level;

phases) on the basis of average `effective' cross-sec-

analytical data on PTS concentrations for 3

tional areas during the 3-day observational periods.

pooled water samples and 3 pooled suspended

Ice thickness was taken into account in the construc-

matter samples from the surface, middle and

tion of the channel profile during the winter low

near-bottom horizons collected over a 3-day

water period.

period;

suspended matter concentrations in 3 pooled

The cross-section areas were subdivided into seg-

water samples collected over a 3-day period from

ments corresponding to the points of flow velocity

the surface, middle and near-bottom horizons.

measurements and sampling. The profile schemes

During the winter low water period, ice thickness was

for each cross-section showing segments are pre-

also measured at each of the cross-sections.

sented in Figures 4.39 to 4.43. The numbers of seg-

ments coincides with the number of observations

For calculations of mean monthly and annual PTS flux-

points.

es through the closing and downstream cross-sections

for the year in which the observations were made, oper-

In order to calculate partial and total mean daily PTS

ational data consisting of water discharge measure-

fluxes in dissolved and suspended form during the typ-

ments at river cross-sections in the area of Oksino and

ical water regime phases, the following assumptions

Igarka settlements were used. These data were provid-

were made:

ed by the Northern (Pechora river) and Central

·

At the closing cross-section, within a given segment,

Siberian (Yenisey river) Territorial Branches of

the PTS concentrations in water and suspended

Roshydromet.

matter do not vary over the time period being rep-

resented, and are equal to the measured concentra-

In order to calculate mean monthly and annual PTS

tion at the corresponding observation point.

fluxes through the closing cross-sections of the rivers for

·

At the downstream cross-section, within the com-

a year with `average' runoff, and to assist in the prepara-

bined segments identified, the PTS concentrations

tion of a brief review of the inter-annual variability in

in water and suspended matter do not vary over the

water runoff via the Pechora and Yenisey rivers, pub-

time period being represented, and are equal to the

lished hydrographical data from 1932-1998, obtained

measured concentrations in the corresponding

from the Roshydromet hydrological network, were used.

pooled samples.

·

Any PTS that were either not found in any of the

Calculation of mean daily PTS fluxes over the 3-day

samples during the entire observation period, or

observation periods was undertaken in several stages:

were found in less than 10% of the total number of

1. evaluation of the river channel profiles at the cross-

samples collected at both the closing and the more

sections where hydrometric measurements were

downstream cross-sections of a river, were excluded

taken;

from PTS flux calculations for the given hydrologi-

2. division of the cross-sectional area into segments,

cal phase.

for calculation of partial discharges and PTS fluxes;

·

Edge effects are not taken into account.

3. calculation of the partial mean daily water and sus-

pended matter discharges (for each segment iden-

An assessment of mean monthly PTS flux (µy) in dis-

tified) and total water and suspended matter dis-

solved and suspended form was made according to the

charges (for the whole cross-section) during each of

calculation method proposed by E.M.L. Beal (Frazer

the typical water regime phases;

and Wilson, 1981).

52

Chapter 4

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

(4.1)

where:

µx mean daily water discharge for the given month

(L/day);

my mean daily flux of the substance under considera-

tion in the dissolved or suspended forms (kg/day),

obtained for a 3-day observation period;

mx mean daily water discharge (L/day), obtained for

a 3-day observation period;

n number of observation days in a month (using

our assumptions three).

and:

Xi, Yi values of the water discharge and flux of the sub-

stance under consideration for each specific day when

measurements were conducted.

In our case Yi=my and Xi=mx, as the concentration of

suspended matter and PTS concentrations were deter-

mined from a single integral sample collected during

the 3-day observation period and the water discharges

were calculated on the basis of the average flow veloci-

ty for a 3-day period.

In this case, equation (1) above for the calculation of

mean monthly PTS flux can be simplified to:

(4.2)

In applying this, the following assumptions were

adopted:

·

Values of my and mx were assumed to be constant

for the months which fall within each hydrological

season: i.e., May-July (spring flood); August-

September (summer low water period); October

(period before the onset of ice formation);

Table 4.12. PCB flux (kg/y) at the closing cross sections of the Roshydromet

November-April (winter low water period).

network, calculated for the period of observations (2001 2002), and for the long term

·

The ratio of the PTS fluxes in dissolved and particu-

mean annual water discharge.

late associated phases is constant inside the cross-sec-

tion and during the hydrological season represented.

·

For the Pechora, mean monthly water discharges at

·

The ratio of the PTS fluxes in dissolved and partic-

the Andeg cross-section were assumed to be equal to

ulate associated phases during the spring freshet is

the discharges at the Oksino cross-section.

assumed to be equal to the ratio during periods of

·

For the Yenisey, mean monthly water discharges at the

low discharge.

Ust'-Port cross-section were assumed to be 3% higher

than the discharges at the Igarka cross-section.

As mentioned above, mean monthly water discharges at

the closing cross-sections of the Pechora and Yenisey

Analytical studies covered the whole range of PTS includ-

rivers (near Oksino settlement and Igarka, respectively)

ed within the project scope, with the exception of dioxins

for both the observation year and an `average' water dis-

and brominated compounds, which were excluded due

charge year, for use in the calculations, were provided by

to their extremely low levels in abiotic freshwater environ-

Roshydromet. For the two downstream cross-sections,

ments. However, analysis of samples collected during field

similar data were not available. Consequently, the follow-

work also showed that levels of toxaphene compounds

ing assumptions were adopted for calculation purposes:

in all samples from the Pechora and Yenisey were lower

53

4.3. Preliminary assessment of riverine fluxes as PTS sources

Chapter 4

than effective detection limits (0.05 ng/L for water,

Although it is difficult to make a definite conclusion

and 0.01 ng/mg for suspended matter), therefore toxa-

regarding the cause of this peak appearance, the fol-

phene was also excluded from the assessment of fluxes.

lowing information should be noted:

·

the peak was observed not only during the summer

4.3.3. Overview of the assessment results

low water period, when it was detected for the first

time, but also during the period before ice forma-

PCB

tion in October (Figure 4.62);

Estimated PCB fluxes via the Pechora and Yenisey

·

the peak is due to increased fluxes in PCB con-

rivers are presented in Table 4.12. It is worth noting

geners associated with suspended matter, with dis-

that the estimated fluxes of specific PCB congeners

solved forms showing practically unchanged fluxes;

through both the closing cross-sections of the regular

·

compared to the spring flood peak, which, as in the

hydrometric network and the downstream cross-sec-