Spring sun, 78°N

SHEBA PROJECT OFFICE

Heavy Metals

The rise of the sun after the polar winter is a

pollution. Overall, lead levels in the atmosphere

time of celebration in the Arctic. The length-

have gone down considerably, mainly thanks

ening days herald warmer weather and the

to restrictions on leaded gasoline. In some

return of migratory animals. But the recent

local areas within the Arctic, however, the use

discovery that the Arctic may be an important

of lead shot for hunting has left particles of

global sink for atmospheric mercury casts a

this metal on the ground or at the bottom of

shadow over polar sunrise.

ponds, a source of exposure for many birds.

Each spring, a substantial amount of air-

Cadmium remains an enigma. Its sources,

borne mercury is deposited on Arctic snow

levels, and biological effects are still not suffi-

and ice as a result of reactions spurred by

ciently well documented to assess the environ-

sunlight. Once in the snow, some of the mer-

mental impact cadmium has in the Arctic.

cury is present in reactive, biologically avail-

In parts of Russia, around the large smelter

able forms. As the snow melts, some of the

complexes in Norilsk and on the Kola Penin-

mercury can enter the food web just as the

sula, emissions that include metals and sulfur

burst of spring productivity begins, a time

dioxide have destroyed all nearby vegetation.

when life in the region is vulnerable.

This chapter also provides updated informa-

This chapter examines heavy metals in the

tion from these areas.

Arctic, focusing on mercury, lead, and cadmium.

In addition to sources, pathways, and levels

Mercury pollution is an increasing concern

of heavy metals, this chapter discusses effects

because levels in the Arctic are already high,

of metals on vegetation and wildlife. Effects

and are not declining despite significant emis-

on people are covered in the chapter Human

sions reductions in Europe and North America.

Health, which shows that mercury, in particu-

Lead, on the other hand, clearly demon-

lar, is a serious health concern for some Arctic

strates the effectiveness of actions to reduce

people.

Coal-burning power plant, 40°N

POLFOTO / T.C. MALHOTRA

38

Introduction

Technological advances have reduced

emissions in some industrial areas, but these

Heavy Metals

Metals are naturally occurring elements. They

reductions have been offset by increases in

are found in elemental form and in a variety

other regions. Many sources are still poorly

of other chemical compounds. Each form or

documented.

compound has different properties, which

affect how the metal is transported, what

Human activities release mercury

happens to it in the food web, and how toxic

it is. Some metals are vital nutrients in low

Mercury is a relatively common metal, found in

concentrations.

rocks, sediments, and organic matter through-

The previous AMAP report assessed a wide

out the world. Typically, naturally occurring

range of metals and concluded that the ones

mercury is strongly bound in these media and

raising most concern about effects in the Arc-

not readily available to the food web.

tic are mercury and cadmium. They have no

known biological function but bioaccumulate

Mercury ore belt

ore be

re

e be

e be

beltt

Parts of the mercury

belt, the geological areas

(see table), can be toxic in small quantities,

Major mercury deposit

er

erc

cu

rcury deposit

rcury

er

y

y

cury

ry

cury

itt

naturally rich in mer-

and are present at high levels for a region re-

cury, lie within the

mote from most anthropogenic sources. For

Arctic.

both metals, a primary emphasis was on

increased understanding of the possible bio-

logical effects of the levels that have been doc-

Uptake efficiency

Half-life

(how much of avail-

(time it takes for

able metal is taken up

the tissue concentration

Metal

Organism

in the indicated tissue) to be reduced by half)

Human activities can mobilize mercury,

Lead

Mammals

5-10% via intestines

40 days in soft tissues

either through mining and subsequent use of

30-50% via the lungs

20 years in bone

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

mercury in a range of products, or by burning

Cadmium Fish

1% via intestines

24-63 days

fossil fuels. In 1995, the most recent year for

0.1% via gills

which global emission figures are available,

Mammals

1-7% via intestines

10-50% of life span in liver

some 2240 tonnes of mercury were released

7-50% via lungs

10-30 years in kidney

into the air as a result of the burning of fossil

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

fuels, the production of metals and cement,

Mercury

Fish

depends on

323 days for organic

the disposal of waste in landfills and incinera-

chemical form,

mercury from diet

tion plants, and other industrial activities.

water temperature,

45-61 days for inorganic

Fossil fuel combustion, particularly burning

and water hardness

mercury from water or diet

coal to generate electricity and heat, was

Mammals

>95% for organic

500-1000 days in seals and

mercury via intestines

dolphins for methylmercury,

>15% for inorganic

52-93 days for methylmer-

Worldwide mercury emissions,

mercury cury

and

40 days for inor-

tonnes/year

ganic mercury in whole

2500

body of humans.

umented in Arctic animals. A third metal of

concern was lead. Lead is also toxic, but envi-

2000

ronmental levels of lead appeared to be de-

creasing as a result of the change to unleaded

gasoline in most countries. Other metals, such

as nickel and copper, were of local concern,

1500

especially near large smelting operations.

Mercury:

1000

sources and pathways

Global emissions of mer-

Coal burning, waste incineration, and indus-

cury to the air in 1995

trial processes around the world emit mercury

from major anthropo-

to the atmosphere, where natural processes

500

genic sources. Estimated

transport the metal. The Arctic is vulnerable

emissions from natural

sources are roughly the

because unique pathways appear to concen-

same as total anthropo-

trate mercury in forms that are available to

genic emissions.

the food web. Environmental changes may

0

have made these pathways more efficient in

Other

recent years.

StationaryNon-ferrous

Waste disposal

metal production Cement production

Natural emissions

fossil fuel combustion

Iron and steel production

39

Current international actions on metals

Heavy Metals

In addition to national regulations concerning emissions and use of heavy metals, some signifi-

cant steps have recently been taken internationally to address the heavy metals.

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN ECE) Convention on Long-Range

Transboundary Air Pollution adopted a Protocol on Heavy Metals in 1998. The protocol targets

mercury, lead, and cadmium. Countries that are party to the protocol will have to reduce total

annual emissions to below the levels they emitted in 1990.

As of June 15th, 2002, there were 36 signatories to the protocol, including all the Arctic coun-

tries except Russia. Of these, 10 had ratified it, including Canada, Denmark, Finland, Norway,

Sweden, and the United States. For the protocol to enter into force, sixteen countries must ratify it.

At its meeting in 2000, the Arctic Council called on the United Nations Environment Pro-

gramme (UNEP) to initiate a global assessment of mercury that could form the basis for appro-

priate international action. This request was based on the findings of AMAP's first assessment.

In 2001, the UNEP Governing Council agreed to undertake such a study. At the same time,

UNEP agreed to tackle the issue of lead in gasoline.

The study on mercury will summarize available information on the health and environmental

impacts of mercury, and compile information about prevention and control technologies and

practices and their associated costs and effectiveness. In addition, the UNEP Governing Council

requested, for consideration at its next session in February 2003, an outline of options to address

any significant global adverse impacts of mercury. These options may include reducing and or

eliminating the use, emissions, discharges, and losses of mercury and its compounds; improving

international cooperation; and enhancing risk communication.

responsible for about two-thirds of these

especially as human activity has increased the

emissions.

total amount of mercury available in the envi-

Recent conversions to cleaner-burning

ronment. Natural sources, such as volcanoes,

power plants and the use of fuels other than

add to the total mercury in the Arctic environ-

coal reduced emissions significantly in West-

ment. It is very difficult to quantify and distin-

ern Europe and North America during the

guish the contributions of re-emitted mercury

1980s. Industrial coal combustion now pro-

and natural sources. For example, a natural

duces only half the mercury that it did at the

event such as a forest fire can release mercury

beginning of the 1980s. There is evidence,

that had been deposited after initial emission

however, that global emissions may now actu-

from a coal-burning power plant.

ally be increasing. The recent reductions have

However, the contribution of natural sources

been offset by rising emissions in some parts

is believed to be comparable, on a global

of the world, particularly Asia, which now

scale, to emissions from human activities.

produces half the world's mercury emissions.

Locally, the contributions of re-emissions vary

The main source of Asian emissions is coal

greatly. About three-quarters of the mercury

combustion to produce electricity and heat,

emitted to the atmosphere is gaseous elemen-

particularly in China. Chinese emissions from

tal mercury, or mercury vapor. About one-fifth

sources such as small industrial and commer-

of the mercury is reactive mercury, and the

cial furnaces, residential coal burning, and

remainder is mercury bound to aerosol parti-

power plants are responsible for about half

cles such as soot.

the Asian total, or one-quarter of global

emissions.

Volatility ensures global distribution

Re-emissions of mercury that has already

been deposited can be a significant source,

Atmospheric transport is the most important

pathway of mercury to the Arctic. Globally,

Anthropogenic mercury emissions,

tonnes/year

an estimated 5000 tonnes of mercury are pre-

1500

sent in the air at any given time. At present,

combustion, particularly of coal in Asia and

Europe, is the most significant source of anthro-

pogenic mercury in Arctic air.

1000

Mercury can appear as a vapor, which means

that it can be re-emitted after it has been de-

posited on land or in water. Long residence

time in the atmosphere, 1-2 years, helps it

500

spread around the northern hemisphere.

The presence of mercury does not by itself

Global anthropogenic

explain how it enters the food web. Elemental

emissions of mercury to

mercury in the air must be transformed into

the air in 1995 from dif-

0

bioavailable mercury. One mechanism by

ferent continents.

Asia

which this can occur has been recently discov-

Africa

Europe

ered, and appears to be unique to the Arctic.

North America

South America

Australia and Oceania

40

5 March

10 March

Heavy Metals

BrO,

1013 molecules /cm2

>

10.0

9.0

Barrow

Barrow

8.0

7.0

6.0

5.0

4.0

<

Polar sunrise

Mercury depletion in

Ozone, ppb

leads to mercury depletion in air

spring 1999 at Barrow,

Hg0, ng / m3

Alaska, one of the sites

4.5

At the monitoring station in Alert, in the

where these events

30

4.0

Canadian High Arctic, the concentration of

Ozone

have been measured.

gaseous elemental mercury levels drops

25

3.5

Lower panel: onset of

3.0

sharply each spring. Researchers first noticed

the main mercury

20

2.5

this phenomenon in 1995, and initially thought

depletion in March.

15

2.0

that their instruments were malfunctioning.

Center panel:

1.5

The phenomenon occurred again the next

Similarity between

10

gaseous elemental mer-

1.0

5

spring, however, and similar observations

Mercury

cury and ozone deple-

0.5

were made at other air monitoring stations

0

tion patterns.

0

around the Arctic.

Upper panel: the

26 27 28 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

February March 1999

The drop in mercury is not a one-time event,

strong mercury deple-

tion on 10 March

but a series that begins shortly after the first

Hg0, ng / m3

coincides with high

sunrise of spring, and continues until snow-

4.0

bromine levels near

melt (see graph to the left). Depletions are

Barrow, which were

3.5

highest at midday, when sunlight is strongest,

not present a few days

3.0

and are closely correlated with a depletion

earlier.

2.5

of ozone in surface air. Although further re-

2.0

search is needed to determine exactly what is

1.5

occurring each spring, a likely explanation is

1.0

a series of chemical reactions in the air.

0.5

The catalyst for these reactions appears to be

bromine, which is emitted from the ocean to

0

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

the surface layer of the atmosphere. Spurred

1999

by sunlight, the bromine reacts with ozone to

create compounds that in turn may react with

Mercury can take many forms

elemental mercury (see diagram on top of op-

Mercury exists in many forms in the environment, each of which

posite page).

has different properties affecting distribution, uptake, and toxicity.

The net result is that elemental mercury

These forms include:

is oxidized to some form of reactive gaseous

Elemental mercury mercury atoms that have not lost electrons.

mercury, while ozone is destroyed. Thus,

At room temperature, elemental mercury is a liquid, but it produces

gaseous elemental mercury and ozone show

mercury vapor (also called gaseous elemental mercury, Hg0), which

a sharp decline together. The mercury and

can be transported by air. Elemental mercury is not particularly

ozone required for these reactions are re-

toxic, but is readily taken up by air-breathing organisms.

plenished from air above the surface layer.

Reactive mercury mercury that reacts readily with other mole-

The gaseous bromine, on the other hand,

cules, and deposits very quickly from the air.

is returned to its original form by the se-

Methylmercury and related compounds mercury joined to

quence of reactions, ready to act as a cata-

methyl groups to form new molecules. Some microorganisms can

lyst again.

turn inorganic mercury into methylmercury, a highly toxic form

Part of the evidence for the role of bromine

that is bioaccumulated and biomagnified.

in mercury depletion events is that mercury

Particulate mercury mercury atoms bound to soil, sediment,

in snow and lichen is higher nearer the coast

or aerosol particles. Particulate mercury is generally not very

than inland. This pattern is the same for sea-

bioavailable.

salt aerosols, which are one source of the bro-

mine necessary for the reactions. Another key

piece of evidence is the finding that mer-

cury in snowfall on the Arctic Ocean in-

creases dramatically after polar sunrise.

Energy from sunlight (h )

Recent mercury transport models have

incorporated the mechanisms thought to

Atmospheric

Atmospheric

transport

transport

be responsible for mercury depletion

into the Arctic

Br

out of the Arctic

2 + h

2Br

events. These models and other calcula-

Br + O

3

BrO + O2

Hg0

Hg0

BrO + Hg0 reactive Hg + Br (?)

tions indicate that the amount of mer-

cury deposited in the Arctic may be con-

siderably higher than previously realized.

Hg0

Br2

Hg0

Br2

Estimates of annual deposition in the

R e a c t i v e H g

Arctic range from 150 to 300 tonnes,

or more than twice the estimates made

without including the springtime deple-

tion events.

Mercury enters the food web

Because the mercury depletion events have

Reactions involving sun-

only recently been discovered, it is not clear

light and bromine remove

Reactive gaseous mercury, unlike elemental

whether they have always taken place. Changes

gaseous elemental mercu-

ry from the atmosphere

mercury, deposits quickly on whatever surface

in Arctic climatic regimes or the levels of

(mercury depletion) and

it touches. During the Arctic spring, this is

anthropogenic pollutants may influence the

transfer it to the surface

most likely to be snow. Once in the snow,

scale of mercury depletion. The chapter

as reactive mercury. Part

much of the mercury is returned to the ele-

Changing Pathways explores the potential

of the reactive mercury

mental form and is re-emitted to the atmos-

role of climate change on mercury transport

may reach the food web;

part is re-emitted as Hg0.

phere. However, a significant amount of the

and deposition.

mercury remains in reactive form in the snow

(see figure to the right), where other processes

Peak daily UV-B, W/m2

convert some of it to a bioavailable form.

Total mercury in snowpack, ng / liter

Reactive gaseous mercury, ng /m3

The bioavailable mercury is likely trans-

0.10

100

1.0

formed to highly toxic methylmercury by

Reactive gaseous mercury

0.09

90

0.9

microbial action. Bioavailable mercury is

Peak daily UV-B

Total mercury in snowpack

negligible in the snow prior to polar sunrise,

0.08

80

0.8

but levels increase after the mercury depletion

0.07

70

0.7

events start, reaching a maximum just before

0.06

60

0.6

snowmelt.

Snowmelt is the time when Arctic plants

0.05

50

0.5

and animals become active and productive.

0.04

40

0.4

Snowmelt is also the main source of freshwa-

0.03

30

0.3

ter to most Arctic landscapes. Though further

Arctic

End of

sunrise

snowmelt

study is needed to determine the fate of the

0.02

20

0.2

reactive mercury, the release of bioavailable

0.01

10

0.1

mercury into terrestrial and aquatic ecosys-

0

0

0

tems may be the chief mechanism for transfer-

1 February

1 March

1 April

1 May

1 June 2000

ring atmospheric mercury to Arctic foodwebs.

Production of reactive

Rivers and biological pathways

gaseous mercury at Bar-

row starts as UV-radia-

can be locally important

tion increases following

Even if most mercury reaches the Arctic

polar sunrise, and ends

at snowmelt. Total mer-

through the air, there are some additional

cury in the surface snow-

pathways. Russian rivers carry mercury

pack also increases over

released by industrial activities upstream.

this period.

Although their mercury concentrations are

much lower than mean global values, the

great volume of water in the Ob, Yenisey,

and Lena rivers make them significant reg-

ional pathways. Together, the Eurasian rivers

transport 10 tonnes of mercury each year to

coastal estuaries and the Arctic Ocean, most

of it in particulate form.

Biological pathways can also be important

locally. For example, salmon migrating from

the ocean to spawn deliver mercury to lakes

and rivers when they die. One study in Alaska

Ob Estuary. Eurasian

estimated that, over the past twenty years, a

rivers transport mercury

BRYAN & CHERRY ALEXANDER

total of some 15 kilograms of methylmercury

to coastal estuaries.

understood, especially for the Arctic. Some

42

mercury enters the food web and some is

Heavy Metals

buried in sediments, but the linkages between

mercury depletion events and mercury concen-

trations in marine biota have not been deter-

mined. It seems likely that the mercury ex-

change between atmosphere and ocean in the

Arctic differs significantly from other oceans

simply because of ice cover. Sea ice forms a

barrier to the gaseous emission of mercury

accumulated in the upper ocean layer, but the

potential of this barrier to enhance mercury

concentrations in the marine environment has

not been evaluated.

Migrating salmon can

serve as a biological

Mercury time trends

pathway for mercury.

BIOFOTO / ADI

Mercury has always been present in the Arc-

has been transported by Pacific salmon to

tic, but levels in many areas of the Arctic are

the lakes and streams of the eastern Bering

considerably higher now than they were

Sea coast.

before the beginning of the industrial era.

While riverine inputs and biological trans-

Recent trends vary geographically and levels

port can be locally significant, analysis of

do not seem to be dropping as would be ex-

mercury and other compounds in sediments

pected from regional emission reductions in

confirms that, across the Arctic, deposition

Europe and North America. In some areas

from the atmosphere is the main source of

they are clearly increasing.

mercury from human activities.

Diagenesis may affect metals profiles

Ocean pathways are not well understood

in sediments and peat bogs

Mercury in sediments and peat bogs may

Atmospheric deposition, including mercury

move after it is deposited, a process known

depletion events, and river inputs supply mer-

as diagenesis. This movement can alter the

cury to the ocean. Mercury is removed from

profile of mercury in the sediment or peat

the upper layers of the ocean by settling of

layers, confounding trend analyses. Although

particles or by emission of gaseous mercury to

there are still questions relating to diagene-

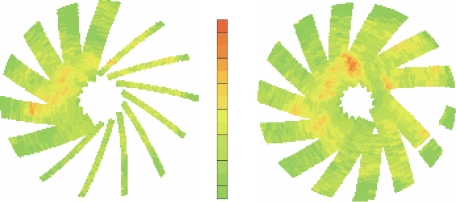

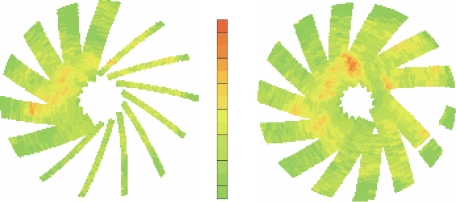

The ratio of post-indus-

the air. The cycling of mercury and its eventu-

sis in lake sediments and peat bogs, a num-

trial to pre-industrial flux

al fate in the ocean, however, are poorly

ber of studies appear to provide good evi-

of mercury to lake sedi-

dence that mercury deposition in the Arctic

ments. Ratios above 1.0

has increased considerably since the indus-

indicate increased mer-

trial era began.

cury deposition in

the post-indus-

trial period.

Mercury levels

are higher than in pre-industrial times

Lake sediments in Greenland show that mer-

cury increases started by the late 19th century,

and perhaps as early as the 17th century.

Recent concentrations are on average three

times higher than in pre-industrial times.

Similar results have been found across Eur-

asia, with increases highest in the west and at

lower latitudes, closer to the industrial areas

of central Europe. Lakes in the Taymir Penin-

sula in northern Russia, for example, showed

a much smaller increase than lakes in north-

ern Scandinavia (see map).

In North America, similar geographic pat-

terns emerged, with higher increases in south-

eastern lakes near mercury sources in eastern

Total mercury flux ratio

North America. By contrast, no increase has

> 0.0 -1.5

been seen in the sediment in some lakes re-

1.5 -2.5

2.5 -3.5

mote from source regions. This includes YaYa

> 3.5

Lake in the Yukon Territory, Lake Hazen

on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian High

Arctic, and lakes on the Arctic coastal plain

`80

`90

`00

of Alaska.

`80

`90

`00

Peat bogs in Arctic Canada, Greenland,

`90

`00

and the Faroe Islands provide evidence sup-

porting the trends found in lake sediments.

`90

`00

Mercury concentrations in cores from these

bogs were seven to seventeen times higher

`90

`00

`90

`00

after the industrial revolution than before.

More information about the behavior of

mercury in peat bogs is needed to interpret

`80

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

the differences between the peat and lake

sediments.

Long-term time trend data for biota are

relatively scarce, but the existing records

`90

`00

show an increase in most parts of the Arctic.

`90

`00

In Greenland, mercury in human and seal

`70

`80

`90

`00

hair shows a three-fold increase since the 15th

century. These data are discussed further in

the chapter Human Health. In Norway, mer-

`70

`80

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

cury in human teeth (without modern mer-

cury amalgam fillings) was thirteen times

higher in the 1970s than in the 12th century,

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

`90

`00

although levels appear to have declined sub-

stantially since the 1970s.

Concentrations in beluga whale teeth from

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

`90

`00

the Beaufort Sea showed an increase of four

`80

`90

`00

to seventeen times between the 16th century

`90

`00

`90

`00

and the 1990s. The data suggest that indus-

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

trial mercury accounts for more than 80% of

`90

`00

total mercury in this species.

`80

`90

`00

`90

`00

`90

`00

`90

`00

Mercury concentration, ng/g

`70

`80

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

500

200

1993

100

of too short duration to provide evidence of

Thick-billed murre

50

(eggs)

definitive recent trends.

Northern fulmar

20

In the eggs of thick-billed murres collected

(eggs)

10

1450-1650

from Prince Leopold Island, Canada, the mer-

Polar bear (liver)

5

cury concentration almost doubled between

Ringed seal (liver)

1975 and 1998. In northern fulmars, the

Beluga (liver)

2

Cod (muscle)

1

increase was 50% over the same period.

Dab (muscle)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

The trend does not appear to be the result of

Burbot (muscle)

Age of animal, years

changes in feeding patterns or the food web.

Pike (muscle)

Arctic char (muscle)

Mercury in teeth of Beaufort Sea beluga collected in 1993,

compared with 300-500 year old teeth.

Mercury levels in kittiwakes showed no signi-

Caribou (muscle)

ficant change, even though these birds migrate

Mollusk shells in Hudson Bay indicate a

to more polluted areas at lower latitudes.

Moose (muscle)

doubling of mercury concentrations in seawater

Mercury in the liver and kidneys of ringed

Blue mussel

since the pre-industrial age. By contrast, mol-

seal, beluga, and narwhal across Canada ap-

(soft body)

Key to coloring of biota symbols

lusk shells and walrus teeth from the Canadian

pears to have increased by a factor of two or

Significant

High Arctic show no change in mercury from

three over the past twenty years, though an-

increasing trend

Increasing tendency

the 16th century to the present, perhaps reflect-

nual variations are high. In the late 1990s,

Significant non-linear/

ing their greater distance from industrial sources.

there was an increase in mercury in beluga

fluctuating trend

No trend

from the Beaufort Sea in the western Cana-

Decreasing tendency

dian Arctic, but no consistent pattern in the

Recent trends vary

Significant

eastern Canadian Arctic. Mercury in ringed

decreasing trend

Where available, trends data from the past

seal liver from West Greenland is higher now

Trends in mercury levels

have been measured over

few decades indicate that mercury levels are

than in the mid-1980s, but in ringed seal from

the past 10-30 years in

increasing in some Arctic biota, specifically in

East Greenland, no change has been seen over

various Arctic species.

marine birds and mammals from some areas

the same period. In polar bear muscle from

Selected time series are

in the Canadian Arctic, and some species in

East Greenland, mercury is higher now than

shown, with animal sym-

West Greenland. By contrast, in lower-order

in the mid-1980s, but no change was found in

bols colored to indicate

the trend. Increasing trends

marine biota samples from the European Arc-

polar bear liver, kidney, or hair.

are apparent in some mar-

tic, mercury levels are stable or declining.

Marine fish and invertebrates show differ-

ine animals, especially in

However, most time trend studies have been

ing trends. In Greenland, mercury in short-

the Canadian Arctic.

horn sculpin increased from the mid-1980s

44

A need for further studies

to the mid-1990s. In Arctic cod over the same

Heavy Metals

period, mercury decreased. Recent collections

The increases in mercury since the start of

of sculpins from Greenland show no clear

the industrial age are clear evidence of the

trend. Cod sampled around the coasts of

role of human activities. Drawing firm con-

northern Norway showed no change in the

clusions about changes in the role of anthro-

1990s. In northwest Iceland, levels in both

pogenic emissions in a shorter time period is

cod and dab declined. In blue mussels, levels

not as easy.

remained stable at most sites in Norway,

The decline in some areas probably reflects

Iceland, and Greenland. Two sites were sam-

decreases in emissions. In Canada, mercury

pled in Prince William Sound, Alaska, one of

levels in sediments have decreased in southern

which showed no change and the other a sig-

lakes, following emissions reductions at near-

nificant increase. In Qeqertarsuaq, Greenland,

by sources. However, there is no clear expla-

mercury declined in larger mussels from 1994

nation for the increases in marine birds and

to 1999.

mammals from some areas in the Canadian

In the terrestrial environment, changes

Arctic and West Greenland or why the time

appear to be occurring in some cases. Moose

trends should be different for Canada/Green-

in parts of the Yukon Territory may have

land and the European Arctic. The Canadian

declining levels of mercury, as measured

belugas that showed the greatest increase in

from 1993 to 1998. Mercury in reindeer

uptake in the 1990s were collected in areas

livers in Isortoq, Greenland declined from

with large freshwater drainage, suggesting

1994 to 1999. Mercury levels in American

that the change could be more related to fresh-

peregrine falcon in Alaska may have in-

water input than direct deposition from the air.

creased from the period 1988-90 to 1991-95.

There is a need to better understand path-

Longer-term monitoring is required to con-

ways and processes influencing mercury distri-

firm these findings.

bution. Such studies should include the pos-

sible influence of climate change, which is

discussed further in the chapter Changing

Pathways.

Mercury levels and effects

Mercury levels in the environment reflect a

combination of different factors, including

Measuring a burbot

pathways and proximity to natural sources.

mercury levels in fish are

related to the size and

Moreover, mercury-rich rocks in some areas

age of the individual.

BIOFOTO / SØREN BREITING

In freshwater environments, the picture is

similarly varied. The only recorded increase is

in male burbot from the Mackenzie River,

Canada. At Fort Good Hope, Northwest

Territories, mercury levels in burbot muscle

increased by 36% between 1985 and 2000.

In other areas where monitoring has occurred,

mercury appears to have declined or remained

stable. Lake trout from Lake Laberge in the

Yukon Territory showed a 30% decline in

mercury in muscle from 1993 to 1996, but no

change from 1996 to 1998. Also in the Yukon,

lake trout in Quiet Lake showed no change

from 1992 to 1999. Arctic char in Resolute

Lake in the Canadian Arctic show no changes

from 1992 to 2000. In northern Sweden,

Arctic char and pike showed no trends over

Mercury ore (cinnabar).

GEOLOGICAL MUSEUM, COPENHAGEN

the past twenty and thirty years, respectively,

although levels fluctuated considerably within

lead to locally higher background levels. Once

that period. In Greenland, no trend was found

mercury enters the food web, differences in

in Arctic char over the period 1994-1999.

food web structure can greatly affect levels of

Levels in freshwater environments may not

mercury, even in the same species in different

respond immediately to declines in emissions

locations. In the Arctic, the potential for bio-

because previous deposition in the catchment

magnification is generally greatest in aquatic

area can make the surrounding soils a con-

food webs, where levels are high enough in

tinuing source.

some species to raise concern about toxic effects.

Mercury can have a variety of toxic effects

45

Heavy Metals

The toxicity of mercury to individual plants

and animals is well known through laboratory

studies and through examining accidents where

mercury was released into the environment or

introduced into food items.

Lavrentiya

In mammals, mercury causes nerve and

brain damage, especially in fetuses and the

very young. It can also interfere with the pro-

Barrow

duction of sperm. In birds, high levels of mer-

cury can cause erratic behavior, appetite sup-

pression, and weight loss. At lower levels,

egg production and viability are reduced, and

embryo and chick survival are lower. Outside

Resolute Bay

the Arctic, some seabirds show signs of cellu-

Arviat

lar-level kidney damage from accumulated

Arctic

mercury. Fish exposed to high mercury levels

Grise

Bay

Fjord

Pond

suffer from damage to their gills and sense of

Inlet

Avanersuag

smell, from blindness, and from a reduced

Salluit

Pangnirtung

ability to absorb nutrients through the intes-

Quataq

Kangirsuk

Svalbard

tine. Plants with high concentrations of mer-

Hudson Strait

Qeqertarsuaq

Ungava Bay

Mercury concentration,

cury show reduced growth.

Nain

ug / g wet weight

Makkovik

Ittoqqortoormiit

15

Mercury is significant

10

in the marine environment

5

The major focus for mercury research has been

on the marine environment. Blue mussels and

0

shorthorn sculpins, two species that have been

Spatial trends in mercury

studied around the Arctic, show no clear spa-

concentrations in ringed

tial trends.

seal liver.

Seabirds, on the other hand, had in general

lower levels in the Barents Sea than in Green-

growth processes are other factors that could

land, Canada, and northeastern Siberia. Ful-

play a role in regional differences.

mars and black guillemots show comparable

There is some evidence that, as one moves

levels between the Faroe Islands and Arctic

westward across the Canadian Arctic, mer-

Canada, though Faroese levels may be closer

cury levels in beluga whales and ringed seals

to the high end of the range for Canadian

increase. In the North Atlantic, mercury levels

samples. The Canadian Arctic seabird data

in minke whales were found to be higher

show an increase in mercury as latitude

around Jan Mayen and the North Sea than

increases.

around Svalbard or West Greenland. In gray

For migratory species, the winter range

seals from the Faroe Islands, mercury levels

may be a critical factor in mercury levels.

are similar to those found in the same species

Birds in northeast Siberia, which winter in

at Sable Island, eastern Canada, but higher

eastern Asia, show higher levels of mercury

than gray seals from Jarfjord, Norway. In po-

than birds in other regions. Moreover, feeding

lar bears, mercury levels are higher in the

habits and food web structure likely play a

northwestern Canadian Arctic than in south-

role in spatial differences. Birds of the same

ern, northeastern, and eastern Greenland.

species may eat invertebrates in one region

and fish in another, with correspondingly dif-

Seabirds and some whales

ferent exposures to contaminants. Regional

may be vulnerable

geology and the effects of temperature on

Documenting mercury levels is an important

step, but these levels do not by themselves tell

us what effects mercury may have on the in-

dividual animals or on wildlife populations.

The natural environment is a complex system,

and different species and even different indi-

viduals can respond in very different ways to

mercury and other contaminants. In most

marine animals, mercury concentrations are

highest in liver, followed by kidney and then

Ringed seal a key

muscle. Polar bears and terrestrial animals

species in circumpolar

BIOFOTO / CLAUS BIRKBØLL

have the highest levels in the kidney.

Arctic monitoring.

Mercury concentration, ug /g wet weight

46

1000

Heavy Metals

100

Liver damage in marine mammals

60

Lethal or harmful in free ranging wildlife and birds 30

Clinical sublethal poisoning of freshwater fish

20

less sensitive fish species

10

Clinical sublethal poisoning of freshwater fish 6

sensitive fish species

Detrimental effects on hatching in terrestrial birds 2

1

Uncertain ranges

0.1

Summary of ranges of

mercury concentrations

in Arctic species, com-

0.01

pared with different

thresholds for biological

effects. The comparison

should be used with cau-

tion because of problems

with extrapolating data

across species.

0.001

, liver

, muscle

, kidney

Polar bear

rrestrial birds, liver

(ducks, geese), eggs Polar bear

e

rrestrial birds, eggsArctic char

Fish (other), muscle

oothed whales, liver

Seals, walrus, liver

T

rrestrial birds, kidney

e

T

Baleen whales, liver

Seals, walrus, kidney

Reindeer/caribou, liver

e

T

oothed whales, kidney

T

T

Baleen whales, kidney

Reindeer/caribou, kidney

Fish (predatory), muscle

Fish (whitefish), muscle

Mammals (carnivores), liver

Mammals (herbivores), liver

waterfowl

Mammals (carnivores), kidney

Mammals (herbivores), kidney

Birds,

Seabirds, gulls, shorebirds, eggs

T E R R E S T R I A L

F R E S H W A T E R

M A R I N E

Bowhead whales, beluga, and seals harvest-

Less is known about freshwater

ed in northern Alaska have concentrations of

and terrestrial environments

mercury and other metals that are high com-

pared with normal ranges found in livestock.

Although there are some spatial differences

Nonetheless, they appear to be in good body

in mercury in the freshwater and terrestrial

condition, with no lesions that would indicate

environments, most levels are low. The differ-

effects of heavy metals. In fact, the levels

ences may reflect local sources, including geo-

found in bowhead whales are comparable to

logy of the local bedrock. In the terrestrial

the levels found in most other baleen whales

environment, there is evidence that mercury

around the world.

accumulates as it progresses up the food web,

Some birds and marine mammals have mer-

and that eating lichen is the primary means

cury levels that are a cause for concern. Stud-

by which caribou and reindeer are exposed to

ies of some seabirds show that higher mercury

mercury.

levels were associated with lower body weight

There are large variations in mercury con-

and lower amounts of abdominal fat. Selenium,

centrations in Arctic char in the AMAP area.

however, may help protect these animals from

Overall, the levels are below the Canadian

the effects of mercury exposure. Seabirds are

subsistence food guideline of 0.2 micrograms

also able to tolerate higher mercury exposure

per kilogram. However, there are areas such

than non-marine birds.

as southwestern Greenland, lakes near Qaus-

0.708 0.291 0.314

uittuq in Arctic Canada, and the Faroe Islands,

where levels exceed the Canadian subsistence

food guideline. The variability can be seen

Mercury concentration,

ug / g wet weight

even in limited geographical regions. For ex-

0.10

ample, in Sweden, levels in the lake Tjulträsket

were four times higher than in the lake Abis-

kojaure (Ábeskojávri), without any obvious

Lavrentiya

explanation.

Arctic char can inhabit different trophic

0.05

levels, even within the same lake. The position

of an individual fish in the food web can also

change over time. Because freshwater fish at

Lake

20

higher trophic levels have higher mercury con-

centrations in their tissues, the position of a

0

given char at a given time is a critical factor in

Lake

23

determining its mercury load. Thus, compar-

Boomerang Lake

Char, North and

isons are difficult to make. Furthermore, char

Resolute Lakes

that spend time in the ocean appear to have

Sapphire

Lake 26

Lake

generally lower mercury levels than land-

Lake 2

locked char.

Lake 1

Fish that eat other fish have higher mercury

Lake 29

levels, and are thus the main concern in rela-

tion to human exposure. These predatory

Zackenberg

species include walleye pike, lake trout, and

Ittoqqortoormiit

northern pike. In the western Northwest Ter-

Kilpisjärvi

Isortoq

Pahtajärvi

ritories, Canada, mercury levels in these spe-

Abiskojaure

Tjulträsket

cies are typically above Canadian consump-

Thingvallavatn

tion guidelines, regardless of size or age.

Faroe Islands

affect mercury availability and uptake. Acidifi-

Spatial trends in mercury

cation, for example, can greatly enhance the

concentrations in land-

process of methylation, producing a higher

locked Arctic char muscle.

proportion of bioavailable methylmercury.

Evidence of effects

in peregrine falcons and grayling

In some birds of prey and in some fish, there

is evidence of biological effects from mercury

exposure. In American and Arctic peregrine

falcons, mercury levels in eggs in one study in

Alaska exceeded the critical threshold for

reproductive effects in up to 30% of eggs,

depending on year and sub-species. American

peregrines, which are also exposed to high

POP levels, have suffered from reduced pro-

ductivity.

Experimental research with freshwater fish

has shown that grayling embryos exposed to

mercury may suffer reduced growth if the

levels are high enough. Later in life, grayling

Ice fishing for Arctic

BRYAN & CHERRY ALEXANDER

char, Igloolik, Nunavut.

exposed even to moderate concentrations of

Other factors affect mercury in freshwater

methylmercury are likely to be poorer at

biota. As discussed above, the presence of

catching prey. This result suggests that mer-

selenium may alter the effects of mercury

cury levels documented in the environment

within an organism, or lower the uptake of

may lower the ecological fitness of grayling,

mercury. This effect could explain a lack of

with the potential to affect the population of

correlation between mercury levels in fish and

grayling in Arctic waters. Similar results have

in sediments in some lakes. Water chemistry,

been found for juvenile walleye pike exposed

especially acidity, and food web structure also

to low levels of methylmercury in the diet.

48

Is it time for global action?

The transport of lead follows seasonal pat-

terns. Lead levels in airborne particles are

Heavy Metals

Temporal trends show a clear rise in mercury

lowest in early fall, and at this time of the

contamination since the beginning of the indu-

year lead reaching the Canadian Arctic comes

strial age. Moreover, in some areas, particu-

mostly from natural sources in the Canadian

larly in North America and West Greenland

Arctic Archipelago and West Greenland.

for marine birds and mammals, mercury levels

In late fall and winter, airborne lead comes

are still increasing. As discussed in the chapter

primarily from industrial sources in Europe.

Human Health, mercury exposure is a signifi-

By late spring and into summer, lead from

cant health risk for some Arctic people.

Asian industrial sources can be detected.

Documenting the circulation of mercury in

the environment and its uptake into the food

Anthropogenic lead emissions,

tonnes/year

web will take more research, and it is vital to

60 000

understand how these processes work. Although

it may not be possible to counteract the toxi-

city of mercury directly, knowing which spe-

cies or areas are most at risk will allow us to

40 000

take other measures to protect them from

additional stresses. It will also help identify

species of concern for human consumption.

20 000

Global anthropogenic

Despite the uncertainties, some things are

emissions of lead to the

clear. Humans contribute a significant portion

air in 1995 from differ-

of the mercury found in the Arctic. The levels

ent continents.

now found in many Arctic animals are cause

0

for concern, even if ecological complexity

Asia

Africa

makes mercury's effects difficult to isolate.

Europe

Oceania

The problem of mercury will not diminish

Australia and

without global action. A first step in this direc-

North America

South America

tion is the UNEP study currently underway, as

Eurasian rivers are also a significant source

described earlier.

of lead delivered to coastal estuaries and the

Arctic Ocean, comparable to the amount of

lead delivered via atmospheric transport.

Lead

Together, these rivers carry some 2450 tonnes

success for political action

of lead each year, most of it in the form of

suspended particles.

Lead is a dense, soft metal with many uses.

Ocean currents may be more important in

Lead is also toxic. Altered behavior resulting

transporting lead to and within the Arctic

from lead affecting brain and nerve tissue is

than previously recognized. While atmos-

the most widely recognized effect of lead poi-

pheric deposition is the initial pathway from

soning. Lead also interferes with many enzymes,

anthropogenic sources to the environment,

most notably those associated with the pro-

most of the lead found in the Arctic Ocean is

duction of hemoglobin and cytochromes.

likely transported by currents from the North

Other effects include kidney damage and

Atlantic and the Laptev Sea. The circulation

dysfunction, anemia, intestinal dysfunction,

and reproductive problems including abnor-

Africa

North America

mal growth and development.

Eastern Asia

Found throughout the world, most lead in

Western and

the environment does not enter the food web,

central Asia

but is adsorbed onto soil and sediment parti-

Asian

cles. Some lead, however, is taken up by

Europe

Russia

plants and animals. It remains a concern in

some areas of the Arctic, but bans on the use

of lead, especially in gasoline, have greatly

reduced emissions and thus global environ-

mental levels.

Eurasia is the major source region

Europe and the Asian part of Russia con-

Different air transport

tribute all but a few percent of the airborne

models give different

lead reaching the Arctic. Models show that

estimates for total lead

the main atmospheric pathways are across the

deposition in the Arctic

North Atlantic, from Europe, and from Siberia.

in 1990, but agree well

on the source regions for

Even in the Canadian High Arctic, analysis

Inner pie: MSC-E model Total deposition: 3.5 ktonnes/year

the lead.

confirms that Eurasia is the main source.

Outer pie: DEHM model Total deposition: 6.1 ktonnes/year

patterns of water and sea ice within the Arctic

Ocean have resulted in most anthropogenic

lead being deposited in sediments in the Eur-

asian Basin. Recent changes in Arctic Ocean

circulation patterns suggest that this pattern

of deposition may also have changed.

Leaded gasoline

has been the most important source

Historically, leaded gasoline has been by far

the most important source of lead to the

Arctic. However, most countries in source

regions to the Arctic have now stopped using

leaded gasoline. This has greatly reduced

emissions to the atmosphere. However,

leaded gasoline is still used in a number of

countries, including Russia, though its use

is declining.

A summary of worldwide anthropogenic

POLFOTO / JENS DRESLING

sources of heavy metals to the atmosphere

showed that in 1995, vehicle traffic emitted

Yukon Territory, and in northern Alaska,

Unleaded gasoline is now

nearly 90 000 tonnes of lead to the atmosphere,

recent lead levels in lake sediments are similar

available in much of the

almost three-fourths of the total. Stationary

to those from pre-industrial times. West Green-

Arctic here at Nuuk,

Greenland.

burning of fossil fuels, to generate heat and

land and Hudson Bay region lake sediments,

on the other hand, show increasing lead con-

Worldwide lead emissions,

tonnes/year

centrations beginning in the 18th and 19th

90 000

centuries.

Ice core data from Greenland indicate that,

along with most other heavy metals, lead lev-

els increased significantly following the Indus-

trial Revolution. By 1970, lead levels were

twelve times what they had been less than two

60 000

centuries earlier. Proto-industrial activities had

been releasing lead before the industrial era,

and the highest modern levels may be as many

as 200 times higher than background levels.

Between the early 1970s, when unleaded gas-

30 000

Global emissions of lead

oline was introduced in North America, and

to the air in 1995 from

the early 1990s, lead deposition on the Green-

major anthropogenic

land Ice Sheet dropped by a factor of 6.5.

sources. Anthropogenic

emissions are about ten

Year

times those from natural

0

2000

sources.

Vehicular traffic

Waste disposal

1950

Cement production

Natural emissions

Iron and steel production

Non-ferrous metal production

electricity, and non-ferrous metal production

Stationary fossil fuel combustion

1900

accounted for another 25 000 tonnes. Data

on sources are likely to underestimate emis-

sions from waste incineration, and so must

be regarded as conservative. The total atmos-

1850

pheric emissions in 1995, however, were almost

two thirds lower than emissions in 1983.

Lead concentrations in a

Greenland ice core show

increases during the

1800

Lead is declining

industrial period, but

in the abiotic environment

decreases since the early

1970s when unleaded

Lead deposition patterns across the Arctic are

gasoline was introduced

in some ways similar to the patterns seen in

in North America.

1750 0

50

100

150

mercury. In the Canadian High Arctic, in the

Lead concentration, pg /g

Air samples taken at Alert on Ellesmere

and Nanisivik Mines in the Canadian Arctic,

50

Island confirm decreases in lead over the past

and the now-closed Black Angel Mine in West

Heavy Metals

three decades. Mosses in northern Sweden

Greenland. The high levels of lead in the

show either stable or declining levels of lead.

rocks at these sites means that levels in nearby

Forest mosses in Finland showed declines in

streams and lakes were already high before

lead levels from the late 1980s to the mid-

the mining began. But mining activities in

1990s, corresponding to declines in bulk

many cases greatly increased releases to the

deposition. These declines are almost certainly

surrounding waters.

a result of the reduced use of leaded gasoline.

Caribou near the Red Dog Mine in north-

Lake sediments in Sweden show declines in

western Alaska have elevated levels of lead in

lead over the past two decades, but also reveal

liver and feces, as might be expected in a min-

that low levels of lead from remote sources

Even after closure, mines

have long been deposited from the atmosphere.

such as Nanisivik, shown

here, can be a source for

contaminants. Here tail-

... but levels in many biota are stable

ings are experimentally

capped with a thick layer

In some areas, lead levels in biota have been

of gravel so that they are

stable in recent years. Lead levels in moose in

fixed in the permafrost

the Yukon Territory showed no change from

layer.

1993 to 1998. In Swedish reindeer, lead declined

significantly in liver, but remained unchanged in

muscle from 1983 to 2000. Other trends in ter-

restrial animals are unclear, largely because mon-

itoring studies have been of too short duration.

Levels in northern pike in Lake Storvindeln

and Arctic char in Abiskojaure in northern

Sweden show no significant trend in lead from

1968 to 1999 and 1981 to 1999, respectively.

One possible explanation for the lack of de-

cline is that this area has received relatively

little lead pollution, and thus has not been

affected by decreases in lead emissions.

BO ELBERLING

eral-rich area. The observed levels, however,

are not high enough to cause concern for

toxic effects.

Industrial facilities such as the smelter com-

plexes at Norilsk and on the Kola Peninsula

also release considerable amounts of metals,

including lead to their surrounding areas. The

effects of this pollution are discussed later in

the chapter.

Lead shot creates problems for birds

While lead from industry and vehicles has de-

clined, local contamination from lead shot has

started to receive attention. Although now

banned in most Arctic countries, the use of

BIOFOTO / SVEN HALLING

lead shot for hunting waterfowl introduced

Reindeer are used to

Walrus at Igloolik in Foxe Basin showed

large quantities of lead pellets into the envi-

monitor temporal trends

no evidence of increased lead in the industrial

ronment. These pellets were, and are, eaten

in metals in Sweden.

era, consistent with findings from lake sedi-

by birds, and the lead is taken up through the

ments and mollusks elsewhere in the Canadian

digestive system.

High Arctic. Levels in blue mussels sampled in

Steller's eiders in Alaska have levels of lead

Alaska and Norway have remained stable for

in their blood that are above avian toxicity

the period 1986 to 1999 and 1992 to 1999,

thresholds for lead poisoning. These birds

respectively.

have suffered from reduced breeding success.

Analyses of livers and kidneys from the eiders

Local lead levels

show that some levels are high enough to

connected to ores and mining

cause concern about toxic effects. The levels

appear to increase over the summer, indicating

Some of the richest deposits of lead ore are

local sources, such as the ingestion of lead

found in the Arctic, for example at the Red

shot found in tundra ponds. These findings,

Dog Mine in northwestern Alaska, the Polaris

although preliminary, suggest that lead shot

may be a significant problem for breeding

Steller's eiders in Alaska.

In an ongoing study in Greenland, there are

no indications of a similar threat from lead

shot to the common eider. White-tailed eagles,

on the other hand, may be poisoned by lead

because they feed on seabirds hunted with

lead shot. In Greenland, lead shot in birds

also appears to be the most important source

for human dietary exposure.

Notes of caution

and possible new threats

Globally, lead emissions have declined sharply

following the introduction of unleaded gaso-

line. But not all sources of lead are well docu-

mented, and levels in some parts of the Arctic

do not appear to follow the declining trend.

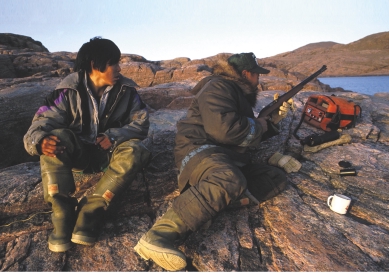

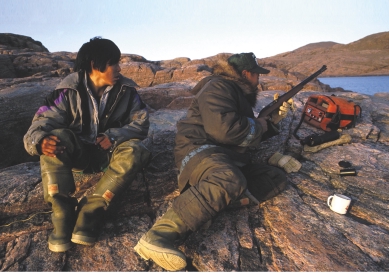

Furthermore, local natural and man-made

sources such as mines, mineral outcrops, and

POLFOTO / EUGENE FISCHER

Hunters, Nunavut

Cadmium

lead shot in the environ-

still largely unknown

ment is a threat to

wildlife and humans.

Like other metals, cadmium occurs naturally

and is also released by human activity. It can

Steller's eider. In Alaska

be taken up directly from air and water, and

this species has high lead

levels, probably from

accumulates in living organisms. Mushrooms

ingesting lead shot.

can be particularly high in cadmium. It can

reduce the growth and reproduction of inver-

tebrates, and interfere with calcium metabo-

lism in fishes. Mammals can tolerate low lev-

Assorted mushrooms

els of cadmium exposure by binding the metal

being dried for storage at

a hunting camp. Preserv-

to a special protein that renders it harmless.

ing mushrooms by dry-

In this form, the cadmium accumulates in the

ing, pickling or canning

kidney and liver. Higher levels of exposure,

is an important seasonal

however, lead to kidney damage, disturbed

subsistence activity in

many areas. In Chukotka,

calcium and vitamin D metabolism, and bone

throughout the year, no

loss. The body takes decades to remove cad-

holiday table is complete

mium from its tissues and organs.

without mushrooms.

STAFFAN WIDSTRAND

lead shot may have a significant impact on

local plants and animals. In cases such as the

Steller's eider, which is endangered in the

United States, effects on an already limited

breeding area may have a major impact on

the population.

An additional note of caution is sounded

by recent analyses of platinum, palladium,

and rhodium in Greenland snow and ice.

These metals are used in the catalytic convert-

ers placed in automobiles to reduce hydrocar-

bon emissions. Their levels in recent snow are

low but still vastly higher than in ice from

thousands of years ago, showing that human

activity is responsible for almost all of the

current deposition in the Arctic. Little is

known about the toxicity and bioaccumula-

tion potential of these elements. Further study

is thus needed to determine the significance of

these results, and to assess whether the bene-

fits of decreased lead are to some extent offset

by the introduction of these other metals.

SVETA YAMIN

52

Cadmium is widespread

Heavy Metals

with localized hot spots

Cadmium is found throughout the Arctic,

but levels vary widely. Arctic char in northern

Canada have ten times the cadmium of char

in northern Sweden. Moose and caribou in

the Yukon Territory have high levels, most

likely due to local geology. Around Disko

Island in West Greenland, locally high levels

of cadmium have been found in blue mussels,

Sundisk through fog over

shorthorn sculpin, and the livers of ringed

meltponds, 78°N.

seals. In spring, deposition of cadmium from

Airborne cadmium

the atmosphere can occur on particles which

adheres to fog droplets

adhere to fog droplets and sea-salt aerosols.

and deposits downwind

from open waters.

It is thus concentrated downwind from open

leads and polynyas.

Broad geographic trends have been found

for cadmium. In Scandinavia, moose in Swe-

den and a variety of mammals and birds in

Norway show a declining cadmium trend

south to north. The distribution patterns fol-

low those of deposition and of accumulation

in forest soils, indicating that long-range

SHEBA PROJECT OFFICE

transport is the source of this contamination.

whales show an increase from west to east

In far northern areas, the observed levels are

across Alaska and Canada. Narwhals appear

very close to background levels.

to have lower levels in West Greenland than

Levels of cadmium in ringed seals are

in the eastern Canadian Arctic, and females

Spatial trends in

highest in northeastern Canada and north-

have higher levels than males. Levels in polar

cadmium concentra-

western Greenland, lower at Barrow, Alaska,

bear are highest in eastern Canada and north-

tions in caribou/rein-

and lowest in Labrador. In Quebec and Lab-

western Greenland.

deer liver italics

rador, there is some indication that cadmium

Other regional patterns have been found,

indicate herds (left)

in ringed seals increases to the north. Beluga

too. Walrus in Alaska have high levels of cad-

and ringed seal liver

(right).

Cadmium concentration,

Cadmium concentration,

ug /g wet weight

ug /g wet weight

1.0

15

10

0.5

5

Lavrentiya

Lavrentiya

Kanchalan

0

Pt. Hope

0

Tay

Red Dog

Mine

Wrangel Island

Finlayson

Bonnet Plume

Barrow

Barrow

Porcupine Teshekpuk Lake

Bluenose

Bathurst

Beverly

Resolute Bay

Cambridge Bay

Khatanga

Qaminuriaq

Taloyoak

Arviaq

Taymir

Dudinka

Arctic

Grise

Bay

Fjord

Pond

Pond Inlet

Inlet

Avaner-

suaq

Cape Dorset

Salluit

Quataq

Pangnirtung

Svalbard

Lake Harbour

Kangirsuk

Hudson Strait

Pechora Basin

Ungava Bay

Qeqertarsuaq

Kangerlussuaq

Itinnera

Nain

Akia

Makkovik

Kola Peninsula

Ittoqqortoormiit

Isortoq

Karelia

Northern Lapland

Central Lapland

Rondane

Hardangervidda

mium, indicating local sources or particular

Worldwide cadmium emissions,

53

food web pathways. In Faroe Islands gray

tonnes/year

Heavy Metals

seals, females have higher liver concentrations

2500

of cadmium than males and other seal species.

The reason for this difference is not known.

Seabirds provide a circumpolar compari-

son. The highest levels are found in northeast-

2000

ern Canada and northwestern Greenland.

Birds in northeastern Siberia have relatively

high levels of cadmium, but may be exposed

in wintering grounds in eastern Asia as well

1500

as in the Arctic. In the Barents Sea, cadmium

concentrations in seabirds are in general lower

than in Greenland, Canada, and northeastern

Siberia. For fulmar and black guillemot, cad-

mium levels in the Faroe Islands are similar

1000

to those observed in Canada, Greenland, and

the Barents Sea. Eiders in Alaska have levels

comparable to Greenland, but higher than in

Global emissions of cad-

Norway.

500

mium to the air in 1995

Mussels give a different picture. Cadmium

from major anthropo-

in mussels is highest in Greenland, due prob-

genic sources. Anthropo-

ably to local geological sources. Alaska has

genic emissions are about

two to three times those

the next highest levels which may explain

from natural sources.

the high levels in Alaskan walrus followed

0

by Labrador and Norway. Mussels from Ice-

land and the Faroes have the lowest levels in

Stationary

the Arctic.

Waste disposal

Cement production

Natural emissions

Human activities are a major source

fossil fuel combustion

Iron and steel production

The processing of zinc ore is the major source

Non-ferrous metal production

of cadmium emissions to the atmosphere.

In the ocean, natural cycling of cadmium is

Non-ferrous metal production accounts for

the most important process for moving the

nearly three-quarters of global anthropogenic

metal. Cadmium is removed from surface

cadmium emissions to the atmosphere. Burn-

waters during primary production of plank-

ing of coal accounts for most of the remain-

ton, and is subsequently returned to deeper

der, with some contributions from other ac-

waters where biotic material decays. This pat-

tivities, such as iron production, cement

tern correlates strongly with the ocean's phos-

production, and waste disposal.

phorus cycle. The Pacific Ocean, which sup-

Estimates of a total anthropogenic release

plies nutrient-rich water to the Arctic through

of about 3000 tonnes in 1995 must be treated

the Bering Strait, therefore also supplies a sub-

with caution. Emissions from waste incinera-

stantial amount of cadmium to the upper lay-

tion and the disposal of municipal waste such

ers of the Arctic Ocean. Although industrial

as sewage are largely underreported. Total

activities may be locally important sources of

releases may be substantially higher. Accord-

Anthropogenic cadmium emissions,

ing to one estimate, natural sources of cadmi-

tonnes/year

um account for only one-quarter to one-third

1500

of total atmospheric releases.

The global significance of human releases

can be seen in the ice core records from the

Greenland Ice Sheet. Cadmium deposition in

the 1960s and 1970s was eight times higher

1000

than in pre-industrial times. Since the 1970s,

however, deposition has declined steadily.

Emissions from non-ferrous metal processing,

in particular, declined by a factor of two or

500

three between the 1980s and 1990s. This

is chiefly the result of pollution-control im-

Global anthropogenic

emissions of cadmium to

provements in major smelters in Europe and

the air in 1995 from dif-

North America.

ferent continents.

0

River transport of cadmium to the Arctic

is comparable to the amount transported by

Asia

Africa

Europe

the atmosphere. As with lead, most of the

Oceania

cadmium is in the form of suspended particles.

North America

Australia and

South America

cadmium levels from 1996 to 2000. The same

is true for moose in the Yukon Territory from

1993 to 1998. Other studies of terrestrial ani-

mals have not gone on long enough to pro-

`80

`90

`00

duce evidence of changes.

`80

`90

`00

In northern pike from Lake Storvindeln

`90

`00

and Arctic char from Abiskojaure in northern

`90

`00

Sweden, cadmium levels remained the same

from 1968 to 1999 and from 1981 to 1999,

respectively.

`90

`00

Over the past two decades, no trends have

`90

`00

been found in cadmium levels in the kidney

and liver of beluga and narwhal in the Cana-

dian Arctic. The same is true for mussels in

Alaska, Greenland, Iceland, and Norway.

Cadmium in livers of shorthorn sculpins in

Uummannaq, Greenland may be declining,

as measured from 1980-1993, but the trend

was not significant. No change was found in

cod and dab in Iceland. Similar consistency

`80

`90

`00

has been found in the muscle of long-finned

pilot whales in the Faroe Islands, though there

is some recent evidence of possible increases.

In ringed seals in Greenland, cadmium lev-

`80

`90

`00

`90

`00

els increased from the mid-1970s to the mid-

`80

`90

`00

`90

`00

1980s, then decreased by the mid-1990s, after

which they have been stable. Changes in feed-

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

ing have been suggested as the likely explana-

`90

`00

`90

`00

tion. Cadmium may have increased in minke

whales in the North Atlantic in recent years,

`90

`00

`90

`00

but further monitoring is needed to confirm

`80

`90

`00

`90

`00

the trend.

`90

`00

`90

`00

`90

`00

`90

`00

`70

`80

`90

`00

Cadmium accumulates

`90

`00

`90

`00

`80

`90

`00

in birds and mammals

In animals, cadmium concentrates in the inter-

Polar bear (liver)

nal organs rather than in muscle or fat. It is

Ringed seal (liver)

cadmium to the ocean, natural processes such

typically higher in kidney than in liver, and

Cod (muscle)

as mixing of water masses, coastal upwelling,

higher in liver than in muscle. Cadmium levels

Dab (muscle)

and primary production are far more impor-

usually increase with age. Kidney levels of

Pike (muscle)

Arctic char (muscle)

tant in determining the marine distribution of

cadmium in caribou in northwestern Alaska,

cadmium.

for example, showed a marked increase with

Caribou (muscle)

age. This is potentially a concern for those

Moose (muscle)

Recent cadmium time trends vary

who eat Arctic animals, particularly if they

favor older adult animals.

Blue mussel

As with mercury and lead, industrial age in-

Bowhead whales in Alaska have non-essen-

(soft body)

creases in cadmium are not found everywhere

tial element levels comparable to those of

Key to coloring of biota symbols

Significant

in the Arctic. Sediments from lakes in the Arc-

most other baleen whales around the world.

increasing trend

Significant non-linear/

tic coastal plain of Alaska and from YaYa Lake

Cadmium concentrations in liver, however,

fluctuating trend

No trend

in the Yukon Territory show no differences

appear higher, perhaps due to the large pro-

Decreasing tendency

between the pre-industrial age and today.

portion of invertebrates in the bowhead diet.

Significant

Walrus from Igloolik in Foxe Basin and belu-

Among birds, there are differences among

decreasing trend

ga from the Beaufort Sea, similarly, show no

species, likely reflecting diet and physiology.

Trends in cadmium levels

change in cadmium levels over the past few

In the Barents Sea region, the highest concen-

have been measured over

centuries, consistent with results from sedi-

trations of cadmium were found in fulmar,

the past 10-30 years in

ment and mollusks in the Canadian Arctic.

kittiwake, Arctic tern, and common eider.

various Arctic species.

In recent years, trends across the Arctic

Common guillemot had the lowest levels.

Selected time series are

vary. Mosses in northern Sweden show stable

shown, with animal sym-

In freshwater fish, in contrast to most spe-

bols colored to indicate

or declining levels of cadmium. By contrast,

cies, cadmium may actually decrease with age,

the trend.

cadmium in liver of reindeer from northern

reflecting changes in predation as the fish

Sweden increased significantly between 1983

grows. Young fish tend to eat invertebrates,

and 2000, though it remained the same in

which have high cadmium levels, whereas

muscle. Moose kidneys in the same region,

older fish often eat other fish, which have

however, showed no significant change in

lower levels of cadmium.

Cadmium concentration, ug /g wet weight

1000

Potential kidney disfunction

400

in marine mammals

Potential liver disfunction

200