Saqqannguaq Road,

Narsaq, Greenland

FINN LARSEN

Changing Pathways

Expect changes and some surprises. These

taminants, the Arctic is not remote or isolated

are the main conclusions from a review of the

from the rest of the world. Human activities in

pathways by which contaminants are trans-

industrial and densely populated areas will

ported to, from, and within the Arctic and

continue to influence what was once thought

how these pathways might respond to shifts

to be a pristine environment.

in climate.

This chapter summarizes current knowledge

During the 1990s, wind and weather pat-

on contaminant pathways and how they relate

terns in the Arctic were quite different from

to climate change. It thereby provides further

the previous three decades. It is too early to

elaboration and discussion of some points

say whether this is part of a natural, recurring

raised in the chapters Persistent Organic Pollu-

change in climate regimes or the result of

tants, Heavy Metals, and Radioactivity, espe-

global warming. Nevertheless, the conditions

cially looking at time trends and future per-

provide some important indications about

spectives. The chapter touches on the effects of

how pathways can change and potentially

long-term climate change in the Arctic. This

alter the load of contaminants to different

topic will be treated in more depth in the forth-

parts of the Arctic. Despite the uncertainty,

coming Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

one truth still stands. When it comes to con-

(ACIA), due in 2004.

European Route E4,

Stockholm

POLFOTO / PELLE ERICHSSON

98

Changing Pathways

Climate change in the Arctic

Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

Climate change and variability, and, more

The Arctic is subject to natural climate cycles.

recently, notable increases in ultraviolet radi-

Some occur over time scales as short as a few

ation, have become important issues in the

years, while others may span decades, cen-

Arctic over the past few decades. Under the

turies, or even millennia. In addition to this

auspices of the Arctic Council, a program

natural variability, the Arctic will be affected

has been initiated to evaluate and synthesize

by global climate changes related to increases

knowledge about climate variability, climate

in greenhouse gases.

change, and increased ultraviolet radiation

The following is a short introduction to

and their consequences. This Arctic Climate

climate change and climate variability in the

Impact Assessment (ACIA) will also examine

Arctic.

possible future impacts on the environment

and its living resources, for example on hu-

man health, and on buildings, roads and

Global climate change

other infrastructure.

will warm the Arctic

Three major documents will be completed

by 2004. They are a peer-reviewed scientific

Human activities, such as the burning of fossil

report, a synthesis document summarizing

fuels, release greenhouse gases to the atmos-

results, and a policy document providing re-

phere. They affect the Earth's energy balance,

commendations for coping with and adapt-

which in turn has the potential to influence

ing to change. The writing of the first two

temperatures and weather patterns. Expert

documents is guided by an Assessment Steer-

opinion, as expressed by the Intergovernmen-

ing Committee with the lead authors, repre-

tal Panel on Climate Change, is that some

sentatives from the Arctic Monitoring and

changes are already apparent. This conclusion

Assessment Programme (AMAP), the Pro-

gram for the Conservation of Arctic Flora

is based on comparisons with past tempera-

and Fauna (CAFF), the International Arctic

ture records and indirect signs of climate var-

Science Committee (IASC), other interna-

iability during the past 1000 years. In the past

tional bodies, and persons representing the

century, the global mean air temperature has

Arctic indigenous peoples.

increased by 0.6 °C. Based on computer mod-

els of the effects of greenhouse gases on the

global climate, the Earth's air temperature

is expected to increase by an additional 1.4

annual mean air temperature may still in-

to 5.8°C over the next century. The range rep-

crease by 5°C near the pole and by 2-3°C

resents uncertainty about future emissions as

around the margins of the Arctic Ocean.

well as an uncertainty about their effects.

However, there are large regional variations,

Climate models show that the warming

even including cooling in some areas.

will be especially pronounced in the Arctic.

The greatest warming will probably occur

Excluding the more extreme predictions, the

in winter. By the end of the 21st century, some

Large cluster of rose

root on stony shore.

Kangerterajiva, Green-

land.

POLAR PHOTOS / HENNING THING

Mean sea ice extent, million km2

Recent climate trends

99

12

follow from Arctic Oscillation

Changing Pathways

10

It is well known that climate can oscillate

Model projections of

8

between different climate regimes. El Niño/

change in sea ice cover

La Niña in the Pacific is one example outside

for the Arctic Ocean.

6

the Arctic. In the Arctic, these climate regimes

Annual mean sea ice

extent is shown for the

are characterized by a high or low Arctic

4

Northern Hemisphere as

Oscillation Index, which captures different

simulated by two different

2

regimes in atmospheric circulation (see box

climate models, which dif-

below). Wind and weather patterns affect ice

fer in how they treat mix-

0

1900

1950

drift and the distribution of water masses in

ing of the water mass.

2000

2050

2100

the Arctic, which in turn can change the extent

models predict that climate change caused by

of ice cover. Changes in air circulation can

greenhouse gases might produce an Arctic

thus influence the transport of contaminants

Ocean that is free of sea ice in the summer.

into and within the Arctic in several ways.

It is not clear to what extent global climate

Since the 1960s, there has been a change in

change has already affected the Arctic. How-

the overall pressure pattern in the Arctic. The

ever, current models predict changes that are

1990s in particular have been characterized by

consistent with observations made during the

lower than average atmospheric pressure over

1990s.

the pole. Expressed in a different way, a low

Winter

Winter Arctic Oscillation Index

0

+

4

0

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

2

The Arctic Oscil-

lation Index since

1960 and the

North Atlantic

Oscillation Index

since 1900. The

Summer

maps represent a

combination of the

Summer Arctic Oscillation Index

Arctic Oscillation

0

+

Index and atmos-

1

pheric pressure

fields during win-

1

ter and summer.

2

1

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

North Atlantic

+

Oscillation Index

1900

1920

1940

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

The Arctic Oscillation and the North Atlantic Oscillation

A leading component of variation in the Arctic's climate is governed by the Arctic Oscillation, which captures different

regimes in atmospheric circulation in the northern hemisphere. Atmospheric circulation patterns can be described by differ-

ences in sea-level air pressure, or the barometer reading in layman's terms. The Arctic Oscillation Index is a measure of sea

surface air pressure patterns. Specifically, it captures winter pressure anomalies north of 20°North.

Strongly correlated with the Arctic Oscillation is the North Atlantic Oscillation, which is a measure of the surface air

pressure difference between the Icelandic Low and the Azores High. This index is an indication of the main wind patterns

over the North Atlantic.

100

Positive Arctic Oscillation Index

Negative Arctic Oscillation Index

(cyclonic)

(anticyclonic)

Changing Pathways

Aleutian Low

Winter

1015

1015

L

L

1015

1015

1015

1025

H

H

L

1005

L

1015

H

Icelandic Low

Siberian High

Positive Arctic Oscillation Index

Negative Arctic Oscillation Index

(cyclonic)

(anticyclonic)

Beaufort High

H

Summer

H

1018

1018

1014

1014

1010

1010

1014

1014

L

Atmospheric pressure

L

L

fields and wind patterns

1018

1010

1014

in winter and summer

1018

1006

with the Arctic Oscilla-

tion Index strongly posi-

tive (left) or strongly

H

H

negative (right).

Arctic Oscillation Index had been replaced by

ing the relative distribution of contaminants

a high Arctic Oscillation Index. The cause for

between the air, land, and ocean. Changes in

this shift is not completely understood. It could

wind patterns, precipitation, or temperature

be the result of natural climate cycles, where

can thus change the routes of entry of conta-

short- and long-term patterns have coincided

minants into the Arctic and the locations at

to produce a very high index in the 1990s.

which contaminants are deposited to surfaces

It could also be a sign of the Arctic responding

or re-emitted to the air.

to global climate change. Regardless of which

explanation turns out to be correct, the

Wind patterns govern pollution transport

changes observed in the early 1990s provide

an example of how the Arctic might respond

The Arctic is characterized by relatively pre-

to global warming, including examples of how

dictable patterns of sea-level air pressure.

climate change may alter the transport of con-

Every winter, high-pressure areas form over

taminants.

the continents, while low pressure cells domi-

nate the northern Pacific (the Aleutian Low)

and the northern Atlantic (the Icelandic Low).

Winds, precipitation

These low- and high-pressure areas pro-

and temperature

duce wind patterns that pump airborne pollu-

tants into the Arctic. The Icelandic Low pro-

The atmosphere provides an important path-

duces westerly winds over the eastern North

way for contaminant transport. Winds carry

Atlantic and southerly winds over the Nor-

contaminants from source regions, while pre-

wegian Sea, which can carry pollution rapidly

cipitation promotes deposition to the land and

from eastern North America and Europe into

the sea. Temperature plays a role in determin-

the High Arctic. Similarly, the Aleutian Low

tends to steer air from Southeast Asia into the

101

Bering Sea, Alaska, and the Yukon Territory.

Changing Pathways

Here, however, the mountains along the west

coast of North America obstruct the airflow,

while intensive precipitation on their western

flanks provides a mechanism to deposit conta-

minants to the surface.

In summer, the continental high-pressure

cells disappear and the oceanic low-pressure

cells are less intense. The result is much

weaker transportation of air and pollutants

into the Arctic from southern areas during

summer.

With a high Arctic Oscillation Index, as in

Difference in winter pre-

the 1990s, the Icelandic low deepens. More-

cipitation between low

over, it extends farther into the Arctic, across

and high North Atlantic

the Barents Sea and into the Kara and Laptev

Oscillation Index.

Seas north of Russia. This increases wind

transport eastward across the North Atlantic,

1.5

1.2 0.9

0.6

0

0.3

0.6

0.9

1.2 mm/ day

across western and central Europe, and into

Difference in winter precipitation

the Norwegian Sea. Also, deep storms with

strong winds become more frequent and ex-

used in many Russian and Eastern European

tend farther into the Arctic.

cars, rains out in the Nordic Seas and in the

The result of this shift in winter wind pat-

southern portion of the Eurasian Basin. Ocean

terns is that the Arctic becomes more strongly

transport is much slower than air transport

connected to industrial regions of North Amer-

and the pollution signal to various parts of the

ica and Europe. The storms also carry rain or

Arctic can thus be delayed.

snow, which can wash contaminants from the

The changes in winds and temperature that

air and deposit them on the ground, on ice, or

are associated with shifts in Arctic Oscillation

in the water.

are likely to affect precipitation. The network

The wind patterns in the Pacific appear to

to monitor changes is sparse, however, and it

change very little in a shift from a low to a

is thus difficult to assess trends. Over a longer

high Arctic Oscillation Index.

time span, the past 40 years, there are indica-

Changes in wind patterns will affect all air-

tions that precipitation has increased over Can-

borne contaminants. For example, spraying of

ada's North by about 20 percent. More mois-

pesticides in eastern North America and Eu-

ture is probably also moving into the Barents,

rope is more likely to show up as peaks in

Kara, and Laptev Seas, carried by the strong

Arctic air measurements during a high Arctic

southerly winds in the Norwegian Sea during

Oscillation Index. Similarly, re-emissions of

autumn and winter. Models for long-term cli-

previously deposited organic pollutants in the

mate change predict that the Arctic will be-

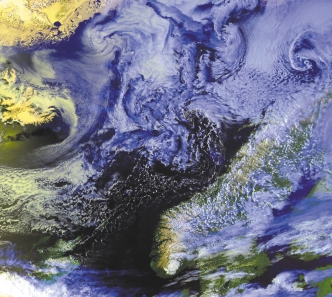

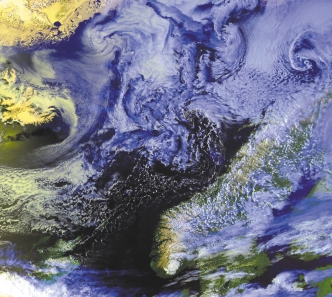

Storm over the Norwe-

soil and water of North America and Europe

come a wetter place, and a greater fraction of

gian Sea. Satellite image.

will enter these same pathways and thus be

transported more readily to the north. How-

ever, as we will see below, increased transport

by air can be offset by other factors.

Precipitation transfers pollutants

from the air to slower ocean currents

Air transport of particle-associated metals

such as lead, cadmium, and zinc will be af-

fected by changing wind patterns. However,

these pollutants are scavenged inefficiently

within the Arctic and thus tend to stay in the

air rather than deposit to the surface. The

actual load to land and sea surfaces in the

Arctic depends strongly on the amount and

kind of precipitation. Changes in snow and

rain patterns thus have a much greater poten-

tial to alter loading than does a change in

wind patterns.

Particulate metals wash out in high precipi-

tation areas. If this occurs over the sea, metals

can then be carried by ocean currents. For ex-

ample, lead from leaded gasoline, which is still

KONGSBERG SATELLITE SERVICES / NOAA

the atmospheric particles that enter the Arctic

extent dissolve in water, such as HCHs and

102

are thus likely to deposit there.

toxaphene. High precipitation in the Nordic

Changing Pathways

Snow and fog are far more efficient than

Seas and southern Eurasian Basin would thus

rain in removing some contaminants from the

increase the role of ocean currents and ice as

air and depositing them to the surface. For met-

pathways. In the Bering Sea, rainout has selec-

als, both a change in the amount of precipita-

tively removed beta-HCH from the air, and

tion or in the relative amounts of rain and snow

switched the mode of delivery to the Arctic

can thus have a large impact on transport.

Ocean from transport by winds to transport

In 1991, the Canadian air monitoring sta-

by ocean currents. Beta-HCH, a component

tion at Alert recorded a marked dip in aerosol

of the pesticide technical HCH, is especially

metal concentrations. It was noted that this

likely to move from air to seawater.

decrease coincided with the economic collapse

that followed the fall of the former Soviet

Most of the Arctic has become warmer

Union, which significantly reduced emissions

of some heavy metals in Russia. However, the

Parts of the Arctic have become warmer in the

air concentrations could also have been af-

past 40 years. In spring, surface air tempera-

fected by the shift toward a high Arctic Oscil-

tures in almost the entire High Arctic show a

lation Index that occurred at this time. It is dif-

significant warming. In the Eurasian part of

ficult to determine the relative importance of

the Arctic Ocean, there is a trend toward a

the two explanations without data that both

longer period of the year when the sea ice is

cover a wide range of sites and span several

melting. As an Arctic average, temperatures

climate change cycles. Nevertheless, the Alert

over land have increased by up to 2°C per

example illustrates that caution must be used

decade during the winter and spring. However,

in assigning causes for contaminants trends in

there are significant regional variations. For ex-

relatively short time series.

ample, on a yearly average basis, the western

Scavenging by rain and snow can also be

Greenland-Baffin Bay area has been cooling.

important for particle-associated POPs, such

Changes in air temperature can have a di-

as some PCBs, and for POPs that to some

rect physical effect on the transport of some

contaminants. This is true for substances

Temperature change,

whose volatility, solubility, and adsorption to

1961-1990,

solids are sensitive to temperature, which is the

°C per decade

case for most POPs. The previous AMAP

0.6 - 0.8

assessment described how volatile contami-

0.5 - 0.6

nants can reach the Arctic from their source

0.4 - 0.5

regions in the south by a series of `hops'.

Higher temperatures in the Arctic would lead

0.2 - 0.4

North Pole

to an increased potential for atmospheric

0.1 - 0.2

transport. Previously deposited organic pollu-

0.2- 0.1

tants would also be volatilized once again and

move back into the atmosphere. On the other

0.3- 0.2

hand, if the temperature difference between

0.4- 0.3

the pole and equator decreases, as predicted

0.5- 0.4

by models, the global thermodynamic contrast

that favors the Arctic as a final reservoir would

weaken. Higher temperatures could also speed

up some of the chemical reactions that remove

pollutants from the atmosphere. Increases in

Temperature anomaly, °C

55-85°N

ultraviolet radiation, which are connected to

Temperature trends for

1.0

ozone depletion in the Arctic, also promote

the Arctic showing the

annual surface tempera-

chemical reactions that destroy or change the

0.5

ture trends over the

form of contaminants.

Average 1951-1980

Northern Hemisphere

0

Even more important than the effects on air

expressed as rates of

0.5

chemistry might be that higher temperatures

change for the period

will lead to more efficient degradation of con-

1961-90 (map), tempera-

1.0

ture anomalies (55-85° N)

1900

1920

1940

1960

1980

taminants by aquatic microorganisms. For

for 1900-1995 evaluated

alpha-HCH, a simple calculation shows that a

against the average for

Temperature change per decade, °C

significant increase in temperature in the upper

1951-1980, and (lower

0.6

water layers of the Arctic Ocean could sub-

panel) the trend by month

Central Arctic Ocean

stantially reduce the environmental half-life of

in surface air tempera-

0.4

ture of the central Arctic

this substance. One model has tried to predict

Ocean for the period

0.2

how an increase in temperature would change

1979-1995 showing the

the health risk from hexachlorobenzene (HCB)

recent warming to be

0

to people in a temperate region. HCB poses a

mainly a winter-spring

phenomenon.

health risk partly because it biomagnifies in

0.2

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

marine food webs and can reach people from

traditional foods. The model implied a reduced

lakes farther south. Specifically, the water col-

103

exposure with increasing temperatures. The rea-

umn will mix earlier, increasing the likelihood

Changing Pathways

son is that higher temperatures would enhance

that contaminants will be retained in the lake.

degradation and also force this pollutant from

Moreover, the warmer water, along with wind

water into the air, reducing the water concen-

mixing and more organic matter from the sur-

tration and, therefore, reducing the amount of

rounding land, may influence primary produc-

HCB entering the bottom of the food web.

tion. A change in the amount or timing of pri-

mary production may increase the opportunity

for contaminants to enter the food web directly.

Changing water flows in rivers

However, it could also lead to more sedimenta-

Changes in temperature and precipitation will

tion, which, at least temporarily, removes con-

affect runoff and flow in Arctic rivers. So far,

taminants to the bottom sediments.

changes in flow seem to be within normal year-

to-year variability. With long-term climate

Permafrost changes may increase

changes, models suggest that the flow in the

mercury cycling and natural radioactivity

Yenisey, Lena, and Mackenzie Rivers is likely

to increase. In other rivers, such as the Ob, it

In the Arctic, ice is a more or less permanent

may decrease. For smaller rivers at high lati-

feature on land. The soil is typically gripped in

tudes, the seasonal patterns of river flow are

permafrost, and only the relatively thin active

likely to change. It is projected that earlier

layer on top thaws in the summer. This layer,

snowmelt in spring would change the timing,

which supports all biological processes and

amplitude, and duration of spring flow.

any vegetation, can be limited to the top meter

There are also some changes in where river

or less. In the 1990s, permafrost degradation

water goes once it has entered the ocean. This

occurred in some parts of Alaska and Russia,

is discussed in the section New pathways in

but not in northeastern Canada. This matches

Arctic Ocean surface waters on page 105.

the distribution of air temperature trends

observed and predicted by climate models.

Permafrost melting will lead to more nutri-

Lakes, land, and glaciers

ents and sediments reaching lakes and rivers.

The flow of organically bound carbon and

Ice can act as a physical barrier for contami-

mercury may also increase. Episodic, large-

nants and also, at times, as a reservoir. What

scale releases of organically bound mercury

happens when higher temperatures melt ice in

may become a dominant feature accompany-

lakes, in the ground, and in glaciers?

ing permafrost degradation. Clearly, Arctic

Lakes are sensitive to changes

Arctic lakes are sensitive to climate change,

as temperatures directly affect the timing of

freeze up in the fall and ice melt in spring.

This, in turn, affects the flow of water to,

within, and from the lake. There are no studies

that show effects of changes in the Arctic Os-

cillation Index on Arctic lakes. In North Amer-

ica, long-term change has been observed, how-

ever. Over the past 100 years, there has been a

delay of several days in freeze-up, while the

spring break-up now comes almost a week ear-

lier than it did a century ago. Changes in water

flow through lakes can have a large impact on

MAGNUS ELANDER

the transport of contaminants. Currently, Arc-

tic lakes appear to retain only a small fraction

lakes would be vulnerable, but increased input

Aerial view of polygon

of the contaminants they receive. The peak in

of carbon is also projected for Arctic seas, sug-

tundra, Lena Delta,

runoff from the snowmelt in their catchment

gesting an increased load of mercury, which

Russia.

areas comes before the ice on the lake has

follows the carbon, in the marine environment.

melted or before the water in the lake has

Hudson Bay may be especially vulnerable due

begun mixing from top to bottom, as it does

to its large drainage basin and because perma-

when the lake warms up in summer. The run-

frost melting is likely in the area. Mercury con-

off, which contains recently deposited contam-

centrations in snow have increased in this area,

inants, therefore traverses the lake just under

as have mercury fluxes to sediment.

the ice or above most of the water column,

Along the coasts, sea-level rise will promote

flowing out as quickly as it flows in.

erosion, which could disturb contaminated

With the reduced ice cover and loss of per-

sites. It may also damage structures such as

mafrost that is expected with climate change,

pipelines, thus releasing potentially contami-

Arctic lakes will probably become more like

nating substances to the environment.

shrinking since the 1960s. In the Canadian

Archipelago, the glacial melt was exceptionally

strong in the 1990s, corresponding to the high

Arctic Oscillation Index. In the European Arc-

tic, the trend is not as clear. Scandinavian glac-

iers have grown during the 1990s, whereas

most Svalbard glaciers continue to shrink at

the same rate as they did throughout the 1900s.

Russian glaciers may be retreating, but this is

difficult to establish because of limited data.

Measurements from the Agassiz Ice Cap in

Canada give a hint of the size of glaciers as a

potential source for contaminants. For DDT,

glacial melt may provide an important climate-

modulated source. For HCHs and PCBs, this

source is small compared with the reservoir in

the Arctic Ocean.

POLAR PHOTOS / HENNING THING

Ocean transport

Glacier at Kangerlus-

Change in permafrost also has an implica-

The Arctic Ocean is divided into distinct lay-

suatsiaq, West Green-

tion for radon that diffuses out of the ground.

ers. Below 800 meters is Arctic deep water,

land. The light grey

This radionuclide is not generally related to

with a very long residence time. From 200 to

zones at each side of the

anthropogenic activities but comes from soils

about 800 meters is the Atlantic Layer. At the

glacier show the former

extent.

and bedrock. Radon is trapped in frozen

very top is the Arctic surface water, which is

ground in the Arctic, but with warmer temper-

the most important for contaminant transport

atures, more radon will diffuse out of soils,

within the Arctic Basin. Between the surface

increasing the dose of this element and its

water and the Atlantic layer is the halocline,

decay products to people.

a transition zone of increasing salinity. The sig-

nificance of ocean transport for contaminants

to, from, and within the Arctic has been in-

Glaciers could become sources of DDT

creasingly recognized during the past few

Glaciers have accumulated snow and ice over

years. Currents are sluggish compared with

millennia. They also act as reservoirs for some

winds, and oceans therefore become important

airborne contaminants. When the glaciers

later in a contaminant's history. However, the

melt, these contaminants can be re-emitted to

ocean may have a much larger capacity to

the air or be released in the meltwater. In the

carry contaminants than the air, allowing cur-

Arctic, North American glaciers have been

rents eventually to catch up with and surpass

Ice

Normal placement of the Atlantic-Pacific front Polar mixed layer

Atlantic-Pacific front

Pacific halocline

during high Arctic Oscillation Index, early 1990s

Atlantic halocline

Bering Strait

Fram Strait

Depth, m

75°N

80°N

85°N

90°N

85°N

80°N

0

ca. 10 years

Bering

200

Pacific water

ca. 10 years

Strait

400

Atlantic water

ca. 25 years

600

ca. 30 years

Atlantic layer

800

1000

Fram

Strait

Arctic deep water

Norwegian Sea

and Greenland Sea

ca. 75 years

deep water

The stratification of

2000

the Arctic Ocean.

Canada

Makorov

showing the polar

Basin

Basin

mixed layer, the

Alpha

Pacific and Atlantic

Ridge

domains of influence

3000

ca. 300 years

Amundsen

Nansen

and the haloclines.

Basin

Basin

The red lines show

the normal placement

ca. 290 years

Nansen

and the displacement

Lomo-

Gakkel

nosov

of the Atlantic Pacific

Ridge

Ridge

front during the high

4000

Arctic Oscillation

Bold figures denote residence times

Index of the early

1990s.

1979

1990-1994

105

Freshwater runoff distribution

Russia

Salinity

Low

Greenland

Alaska

High

620

430

85

525

Changes in the distribu-

tion of freshwater runoff

600+

in the Arctic Ocean be-

600+

Atlantic-Pacific

2000

tween low Arctic Oscil-

Front

Atlantic-Pacific

Front

lation Index, 1979, and

200

high Arctic Oscillation

200

?

Index, 1990-94 (upper

maps), and changes in

Pre 1990

Post 1990

330

330

the amounts of river in-

Low Arctic Oscillation Index

High Arctic Oscillation Index

River inflow, km3/year

River inflow, km3/year

flow to the Arctic Ocean

under same conditions.

atmospheric transport in importance. Some of

reduction in stratification in the Eurasian

the ocean pathways have already exhibited

Basin and increased stratification in the Can-

changes clearly related to the Arctic Oscillation.

adian Basin.

The diversion of the Russian river outflow

affects the transport of persistent organic pol-

New pathways

lutants both from the rivers and within the Arc-

in the Arctic Ocean surface waters

tic Ocean. Specifically, instead of entering the

Surface ocean water pathways follow two

Transpolar Drift to exit the Arctic Ocean with-

basic trajectories: the Transpolar Drift that

in about two years, the pollutants would enter

crosses the Eurasian Basin and exits through

the Canadian Basin, which has a ten-year resi-

Fram Strait, and the circulating Beaufort

dence time. Pollutants would thus stay in the

Gyre on the North American side of the

Arctic Ocean much longer, especially increas-

Arctic Ocean (see figure on page 3). With a

ing the load in the Canadian Basin. Further-

high Arctic Oscillation Index, water in the

more, once in the Canadian Basin, pollutants

Transpolar Drift moves closer to North

from Russian rivers might then exit via the

America, while the Beaufort Gyre retreats

Canadian Archipelago instead of via the west

into the Canadian Basin.

side of Fram Strait. The increased residence

More important than changes in trajectories

time would lead to increased sedimentation,

Driftwood from Siberia

found at Fleming Fjord,

are the effects on the halocline. This is a transi-

making it likely that more sediment-bound

north of Ittoqqortoor-

tion zone of increasing salinity, which serves as

contaminants would remain in the Arctic.

miit, East Greenland.

a barrier for transfer of heat and contaminants

from Arctic surface water to the Atlantic water

below. In the 1990s, the halocline in the Eur-

asian Basin weakened. The most likely reason

was that changes in wind patterns forced

freshwater from the Russian rivers emptying

into the Laptev and Kara Seas eastward, di-

verting their flow toward the East Siberian

Shelf. The freshwater input to the Arctic Ocean

is important for the development of stratifica-

tion in the water column. A consequence of

this diversion, therefore, would have been a

POLAR PHOTOS / HENNING THING

marine environment. In the past few decades,

106

High North Atlantic Oscillation Index

the North Atlantic Oscillation Index has in-

Changing Pathways

creased, causing changes in distribution of

water masses in the Nordic Seas. This has

brought contaminants from the reprocessing

plants closer to the Norwegian coast and into

the Barents Sea.

Traditionally, the Arctic Ocean has been

thought of as a quiet, steady-state system char-

acterized by several relatively stable layers.

During the 1990s, there were some spectacular

changes. The front between Atlantic and Pa-

cific water was forced closer toward North

America, which increased the Atlantic's area of

influence in surface water by some 20 percent.

Water in the Atlantic layer is both warmer and

Low North Atlantic Oscillation Index

saltier than the Pacific water that it displaced.

The declining role of Pacific water in the

Barents

Arctic Ocean has implications for cadmium,

Sea

a toxic metal that biomagnifies in the marine

Greenland

food web. In the ocean, the distribution of this

Sea

metal is largely controlled by natural biogeo-

Norwegian

Sea

chemical cycles, with the Pacific having higher

Iceland

Sea

natural concentrations than the Atlantic. Be-

cause the Pacific inflow through the Bering

Irminger

Strait is a dominant source to the surface

Main features of ocean

Sea

Labrador

waters of the Arctic, reduced Bering inflow

circulation in the North

Sea

since the 1940s has probably led to reduction

Atlantic and the Nordic

Seas during high and low

in cadmium input. Furthermore, the encroach-

North Atlantic Oscilla-

Atlantic water

Arctic water

ment of Atlantic water during the recent high

tion Index.

Arctic Oscillation Index will have reduced the

The Atlantic's increased role leads to

domain of Pacific water that is relatively en-

declines in cadmium

riched with cadmium within the Arctic. Changes

in upwelling or mixing are also likely to affect

For the Atlantic Layer, the Arctic Oscillation

the entry of cadmium into surface water from

influences the flow of water into and out of the

deeper layers.

Arctic Ocean. Communication with the Pacific

is through Bering Strait, while communication

An exceptionally strong

with the Atlantic is through Fram Strait and

shift to high Arctic and

Sea ice

through the Norwegian and Barents Sea. Im-

North Atlantic Oscilla-

tion Indices in about

portant contaminants in the Atlantic inflow

One of the prominent features of the Arctic

1989 increased the influ-

include radionuclides from European repro-

Ocean is its ice cover. Changes in ice cover

ence of Atlantic water

cessing plants, and any change in the flow of

have already occurred and the effects of this

(red) in the Arctic basin.

Atlantic water may thus affect concentrations

on persistent organic pollutants and mercury

The Atlantic layer cur-

rents are relatively fast

and distribution of radionuclides in the Arctic

may become increasingly important.

and move water at a rate

of 300-1600 kilometers

Low Arctic Oscillation Index

High Arctic Oscillation Index

per year along the mar-

gins of the basin.

Alaska

Temperature

Warm

Russia

Cold

Greenland

Winter maximum

Summer minimum

107

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

Changing Pathways

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

Total ice cover

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;

Partial ice cover

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;

Open water

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

Winter maximum and

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

summer minimum Arctic

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

sea ice cover as derived

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;

from satellite imagery.

than multi-year ice because it is thinner and

Less ice cover

saltier. In the East Siberian and Beaufort Seas,

During the 1990s, the scientific community

there were unusually large areas of open water

recognized with some alarm that Arctic sea ice

in late summer at various times during the

had retreated over the past three decades. The

1990s. It appears that the marginal seas are

changes included a reduction in the area cov-

becoming only seasonally covered with ice,

ered by sea ice, an increase in the length of the

and that the extent of the permanent ice pack

ice melt season, and a loss of multi-year ice.

is decreasing.

The rate of loss has been difficult to estimate

The loss of sea ice is consistent with what

but is approximately 3 percent per decade.

can be expected under a high Arctic Oscil-

Most of the ice has been clearing during

lation Index. Several factors are probably

summer over the shelves of the Eastern Arctic,

involved including more heat being trans-

north of Russia. Multi-year ice has decreased

ported to the pole by southerly winds. Even

even more rapidly and been partly replaced by

more important might be that winds cause

first-year ice. First-year ice melts more easily

changes in the distribution of ice. Ice-thickness

measurements made from submarines indicate

Sea ice extent, million km2

that the multi-year ice in the Central Arctic

8.0

Ocean has been getting thinner. Most of the

Monthly averages

7.0

information has been gathered in the interior

of the Arctic Ocean, and the decrease might

6.0

be, at least in part, the product of a shift in the

5.0

distribution of multi-year ice toward North

4.0

America.

Sudden but temporary changes in ice cover

1.0

Monthly deviations

have occurred earlier in Arctic history. Over a

0.5

century ago, the whaling fleet experienced a

0

dramatic decrease in ice cover in the North

American Arctic. In the Barents Sea, about 15

0.5

percent of sea ice cover was lost around 1920.

1.0

1980

1985

1990

1995

Increased exchange of POPs

Sea ice extent,

change per decade, %

between sea and air

0.5

Some persistent organic pollutants have accu-

0

mulated in the Arctic Ocean surface waters.

0.5

The low temperatures of the Arctic, which

1.0

decreases their volatility in air and increases

1.5

their tendency to dissolve in water, acts as a

2.0

driving force in moving them from the air to

The change in Arctic

Ocean sea ice extent

2.5

the water. This pathway is especially important

from 1979 to 1995

for compounds that prefer cold water, alpha-

showing the ice loss to

3.0

HCH being a prime example. Once these pollu-

be predominantly a late

3.5

tants are in the water, they can become trapped

wintersummer phenom-

4.0

enon.

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

S

O

N

D

under the ice and retained in the water masses,

Month

some of which have long residence times.

108

Low Arctic Oscillation Index

Russia

High Arctic Oscillation Index

Changing Pathways

Transpolar Drift

Transpolar Drift

Beaufort Gyre

Beaufort Gyre

Ice drift patterns for

years with low and high

Canada

Greenland

Arctic Oscillation Index.

For alpha-HCH, discontinued use of the

deposition would decrease, and at the same

pesticide technical HCH has led to a drastic

time more mercury could escape back to the

reduction in air concentrations. As a conse-

atmosphere after being deposited. The end

quence, the ice-covered areas of the Arctic

result would be less accumulation of mercury

Ocean became oversaturated relative to atmos-

in marine and aquatic environments. It is

pheric levels. If the ice cover disappears, these

harder to predict whether levels in biota

areas will become a source to the atmosphere.

would also change. Mercury biomagnifies

Other contaminants, such as PCBs and toxa-

and its levels depend on the structure of the

phene, are still loading into the Arctic Ocean

food web. Changes in the food web structure

from the air. The same loss of ice cover could

could, therefore, be much more important

thus lead to increased loading of these two

than changes in physical pathways. Mercury

contaminants into Arctic surface water.

levels may also be affected by changes in per-

mafrost, and increase with an increased flux

of organic carbon to both freshwater and

Ice changes will affect

marine environment. In summary, the com-

mercury deposition in the Arctic

plexity of mercury pathways combined with

As described in the chapter Heavy Metals,

obvious sensitivities to climate change should

mercury deposition in the Arctic increases dra-

alert us to the possibility of surprises in the

matically at polar sunrise due to an extraordi-

future.

nary set of circumstances. The phenomenon is

called mercury depletion. Although the mech-

Shifting routes from drifting sea ice

anisms behind mercury depletion are not yet

fully understood, results of investigations to

The general patterns of ice drift have been rec-

date indicate that gaseous mercury in the air

ognized since the beginning of the 1900s, and

reacts with bromine compounds to form par-

follow the same trajectories as ocean surface

ticulate and reactive mercury. The bromine

water in the Transpolar Drift and the Beaufort

compounds are formed when bromine, emitted

Gyre. Only recently have these ice trajectories

from seawater and sea salts, reacts with ozone

been mapped in detail. The new data suggest

in the presence of ultraviolet light (hence the

that there are two characteristic modes of ice

connection to the return of the sun). The reac-

motion, one during a low Arctic Oscillation

tive mercury that is produced is efficiently re-

Index and one during a high index. During a

moved from the atmosphere and some of it

low index, which prevailed from the 1960s to

remains in the snow. Some will eventually end

the 1980s, the Transpolar Drift moves ice di-

up in meltwater and may thus enter aquatic

rectly from the Laptev Sea across the Eurasian

ecosystems. The sensitivity of the Arctic to

Basin and into the Greenland Sea. By contrast,

mercury probably lies in the fact that meltwa-

during a high index, the prevailing situation

ter and runoff can drain into surfaces below

for much of the 1990s, this ice transport route

the ice, where ice cover blocks the re-emission

is diverted or splits. Some goes to the Green-

of mercury to the air.

land Sea and some moves across the Lomono-

Change in sea ice cover can affect this

sov Ridge and into the Canadian Basin. At the

unique deposition mechanism if the availabil-

same time, the Beaufort Gyre shrinks back into

ity of bromine is altered. Initially, it is likely

the Beaufort Sea and becomes disconnected

that climate change will contribute to increas-

from the rest of the Arctic Ocean. This means

ing the amount of first-year ice around the

that it exports less ice to the East Siberian Sea

polar margins, leading to saltier ice and snow.

and only imports a little ice from north of the

It could thus enhance the emission of bromine

Canadian Archipelago.

and possibly extend the area of mercury deple-

The changes in ice-drift patterns have impli-

tion events.

cations for the transport of sediment and any

With further climate change, parts of the

contaminants trapped in the ice. Specifically,

Arctic will become more temperate. Mercury

when ice moves away from the East Siberian

and Laptev Seas, new thin ice can form close

spawning grounds to their nursery areas.

109

to the coast, increasing the opportunity for

Atlantic cod and its main food item capelin

Changing Pathways

sediments to be trapped. Moreover, less ice

are likely to move northeastwards. Spring-

moves from the North American to the Eur-

spawning herring may return to the same

asian part of the Arctic Ocean.

migration route they followed in the mid-

1960s, when the water temperature around

Iceland was higher than today. Other more

Biological impacts

southerly species may become distributed

Climate change will have impacts on plants

and animals in the Arctic and thus on the bio-

logical pathways for contaminants. Although

Capelin

we can infer the types of changes that are

likely to occur, we cannot predict their scope

and timing. The following are examples of

Cod

processes that should be examined further.

N O R W E G I A N S E A

Changing plant cover

will affect deposition

Herring

Vegetation provides surfaces onto which air-

borne contaminants can deposit when air

Mackerel,

Mackerel

blue tuna

masses pass over the land. Forests, for exam-

ple, have a unique ability to take chemicals

North Sea

herring

from the air via foliage and thence to a long-

Possible changes in the

term reservoir in the soil.

distribution of fish spe-

cies if the seawater tem-

Warmer winters will promote growth of

Anchovy, sardine

perature increases 1-2 °C.

woody shrubs and stimulate a northward

migration of the treeline. So far, there is no

farther north toward and into the Arctic. This

evidence of large changes on the Arctic tundra.

will lead to the introduction of new species

However, if permafrost melts and the water

into the Arctic marine ecosystem. The conse-

table changes, such changes could occur much

quences are difficult to predict but may include

more rapidly in the Arctic than in other regions

changes in the food web and thus in the load

of the world.

of contaminants in biota. Another possibility

is changes in migratory routes and contami-

nants along the route.

Aquatic ecosystems

are sensitive to changes

Changes in sea ice

Not only temperature but also changes in light

can alter marine ecosystems

and the flow of nutrients will affect freshwater

ecosystems. For example, loss of permafrost

In marine ecosystems, many contaminants are

will increase inputs of nutrients from the sur-

biomagnified in food webs, particularly those

rounding soil. Spring algae blooms will prob-

with many trophic levels. Therefore, any

ably come earlier.

changes in food web structure can potentially

In the summer, increased water temperature

have a large impact on contaminant burdens in

will negatively affect fish species that are sensi-

top predators. The changes can be initiated at

tive to temperature or have temperature thresh-

the bottom of the food web, for example if

olds during their spawning. Each species has to

changes in light and nutrient cycles alter con-

be evaluated separately, but trout and grayling

ditions for phytoplankton and zooplankton.

are known to be sensitive. Increased winter

Food-web changes can also be initiated at the

temperatures will enhance microbial decompo-

top, by altering predation patterns, for exam-

sition. Insects, phytoplankton, and zooplank-

ple among bears and seals.

ton will also be affected, some positively and

The amount of sea ice influences both light

some adversely.

conditions and the distribution of nutrients in

Along the North American Arctic coast, the

the water. Change in stratification of the

loss of estuarine ice may displace cisco, which

water column is important in this respect and

might be replaced by anadromous fish from

a decrease in mixing of water layers has

the Pacific Ocean.

already been noted in the Greenland Sea and

For marine fish, it is well known that

in the Canadian Basin. The availability of

changes in climate or ocean currents can affect

nutrients influences the algae that are respons-

the distribution of commercially important

ible for primary production at the bottom of

stocks, such as Atlantic cod and herring. Water

the food web. This is true for the phytoplank-

temperatures are important, as are the distrib-

ton in the water column and also for the algae

ution of prey and predators and the currents

that grow on the bottom of the ice and sup-

that determine the movement of larvae from

port a unique ice-associated food web. Some

of the algal production falls to the bottom of

this bird species. The change in quantity of

110

the ocean, where it supports the benthic food

different zooplankton probably also decreased

Changing Pathways

web. The distribution of sea ice thus has a

food availability for fish, whales, seals, and

major impact on the distribution of organic

walrus, causing die-offs and long-distance

matter between the water column and the

displacements.

seabed.

Loss of sea ice would lead to Arctic shelf

The Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, crossed

seas looking more like temperate seas. The

during the drift of the SHEBA (Surface Heat

implications for food web structures are very

Budget of the Arctic Ocean) Project in 1997-

difficult to predict and we should be prepared

98, provide a dramatic example of a large-

for surprises. One such warning sign was the

scale bottom-up change in the marine food

massive blooms of jellyfish in the Bering Sea

web. Compared with a study 20 years earlier,

during the 1990s. Large-scale changes pro-

this new close look at life in the water revealed

duced by the Arctic Oscillation have the poten-

a marked decrease in large diatoms and large

tial to alter the balance between upwelling and

microfauna within the ice. The high Arctic

downwelling along the coast, through changes

Oscillation Index of the 1990s had diverted

in either the distribution of ice cover or in

river water into this area, causing a strong

average wind speed and direction. Shifts in the

stratification of the surface waters. The result

Arctic Oscillation thus have the capacity to

was a decrease in the supply of nutrients from

cause large-scale shifts in shelf ecosystems. In

below, and a species composition that was

regions that are important for commercial fish-

more typical of freshwater ecosystems. The

eries, such changes can have major impacts on

loss of large diatoms could potentially produce

the regional economy.

a shift toward smaller zooplankton grazers,

Sea ice is also a crucial habitat for many

perhaps then introducing an extra step at the

species at the top of the food web. Ringed

bottom of the food web.

seals need landfast ice for pupping, which in

turn influences the migration of polar bears

that feed on the ringed seals. A decrease in

suitable habitat for ringed seals to pup could

lead to declines in their populations, with the

possible consequence that polar bears could be

forced to find other food sources or starve.

Ringed seals feed on Arctic cod. If changes in

the ice alter the balance between seals and

polar bears, they would likely affect the Arctic

cod as well.

Walrus provide an excellent example to

challenge our predictive capability. Most wal-

rus feed on bottom-dwelling organisms and

are thus fairly low in the food web. Some wal-

rus, however, are known to eat seals, and their

higher position in the food web is reflected in

higher contaminant levels. Many walrus use

drifting ice for their haulouts because it pro-

vides good access to nearby feeding areas,

reducing the amount of energy required to

feed. If the summer ice edge retreats north of

the relatively shallow areas where walrus can

feed, as happened in the summer of 1998 in

the Chukchi Sea, the walrus may be forced

either to starve or to prey on seals. The latter

adaptation would place walrus much higher in

the food web.

Less sea ice could, however, benefit other

species. Eiders, which also feed on the ben-

M A G N U S E L A N D E R

thos, need open water in which they can dive.

Walrus grazing on mussels.

The Bering Sea provides another recent

By benefiting some species and hindering oth-

Most walrus feed low in the

example of how bottom-up changes can per-

ers, the loss of sea ice is likely to cause major

food web, for example by

meate an entire ecosystem. In 1997-98, there

alterations in the marine food web. This is

grazing on mussels. How-

were massive blooms of small phytoplankton.

particularly true for changes caused in certain

ever, some individuals hunt

seals, thus receiving higher

Because they were smaller than the diatoms

key species. Arctic cod, for example, plays a

contaminant intakes. If cli-

that typically bloom in the Bering Sea, they

central role linking lower levels of the food

mate change were to cause

were grazed on by copepods instead of

web to seals, beluga, and many birds. Any

a shift in feeding habits, it

euphausiids. The short-tailed shearwater nor-

changes to Arctic cod abundance or distribu-

would thus have implica-

tions for contaminant lev-

mally feeds on the euphausiids, and the lack of

tion could propagate both up and down the

els in this species.

food may have contributed to a large die-off of

food web.

111

Changing Pathways

Tourists visiting the

North Pole on an ice-

breaker cruise take the

BRYAN & CHERRY ALEXANDER

Polar Plunge.

transport of airborne pollutants from eastern

Human activities will increase

North America and Eurasia. Another example

Climate change will inevitably bring changes to

is Atlantic water carrying more radionuclides

human activities in the Arctic, with subsequent

from European processing plants. Lead that

effects on contaminant loads and pathways.

has been deposited in the ocean to the west

For people, food habits have a great impact

of Europe would also follow this pathway.

on exposure to contaminants. Changes in

A third example is the longer residence time

hunting opportunities because of changed ani-

in the Arctic Ocean for contaminants that are

mal distribution and availability or changed

carried by ocean surface waters.

ability to travel over ice or land will thus have

Long-term climate changes are likely to

an impact. If a hunted animal is suddenly

affect pathways that are influenced by sea ice.

higher in the food web, its contaminant load

Such pathways will be important for many

could increase, thus increasing exposure even

persistent organic pollutants that partially

for people whose food habits remain the same.

dissolve in water, some of which are currently

A warmer Arctic with less sea ice will also

trapped under the ice. Mercury is likewise

encourage shipping, tourism, and oil exploita-

trapped under ice. For mercury, changes in sea

tion, all of which increase the risk for contami-

ice cover may also influence newly discovered

nation of new areas. More severe storms

physical pathways that enhance the deposition

would further increase risks connected to ship-

of mercury to surfaces.

ping and other offshore activities. The expan-

Changes in lake ice and permafrost will

sion of commercial fisheries from the Arctic

affect lake hydrology, potentially increasing

marginal seas into the Arctic Ocean would

the input of contaminants into freshwater

also likely affect food web structure and rela-

ecosystems and possibly releasing contami-

tive abundance of many species. Although the

nants that have accumulated in soil or have

net effects of changes in human activities and

been improperly disposed of in earlier times.

behavior in the Arctic are impossible to predict

Many contaminants pose a problem in the

with confidence, changes are certain to occur.

Arctic because they biomagnify in food webs.

They, in turn, will affect sources, pathways,

Changes in food web structure, therefore,

and eventual fate of contaminants in the Arc-

have a great potential to alter contaminant

tic, including human exposure.

levels in top predators. However, the com-

plexity of ecosystems and our incomplete

understanding of the dependence of many

Summary

species on habitats like sea ice make it espe-

cially difficult to predict change, and one

Long term-climate change and natural climate

should expect surprises.

cycles affect the transport of contaminants to

A final conclusion is that the load of per-

and within the Arctic. The 1990s provided an

sistent organic pollutants, heavy metals, and

example of how widespread change can rapidly

radionuclides in the Arctic is dependent on

pervade much of the Arctic including winds,

many factors that operate after the contami-

weather patterns, ocean currents, and sea ice.

nant has been released from its source. In the

It is, however, difficult to predict whether long-

long run, anthropogenic emissions that affect

term climate change will lead to a generally

the climate may become as important as the

decreased or increased contaminant load.

emissions of the contaminants themselves in

Some pathway changes clearly lead to more

determining the extent to which these con-

efficient transport, one example being increased

taminants reach and affect the Arctic.