Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Other reports in this series:

Russian Arctic GIWA Regional assessment 1a

Caribbean Sea/Small Islands GIWA Regional assessment 3a

Caribbean Islands GIWA Regional assessment 4

Barents Sea GIWA Regional assessment 11

Baltic Sea GIWA Regional assessment 17

Caspian Sea GIWA Regional assessment 23

Gulf of California/Colorado River Basin GIWA Regional assessment 27

Yellow Sea GIWA Regional assessment 34

East China Sea GIWA Regional assessment 36

Patagonian Shelf GIWA Regional assessment 38

Brazil Current GIWA Regional assessment 39

Amazon Basin GIWA Regional assessment 40b

Canary Current GIWA Regional assessment 41

Guinea Current GIWA Regional assessment 42

Lake Chad Basin GIWA Regional assessment 43

Indian Ocean Islands GIWA Regional assessment 45b

East African Rift Valley Lakes GIWA Regional assessment 47

South China Sea GIWA Regional assessment 54

Sulu-Celebes (Sulawesi) Sea GIWA Regional assessment 56

Indonesian Seas GIWA Regional assessment 57

Pacifi c Islands GIWA Regional assessment 62

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment 44

Benguela Current

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Editorial assistance: Johanna Egerup, Malin Karlsson

Maps & GIS: Rasmus Göransson

Design & graphics: Joakim Palmqvist

Global International Waters Assessment

Benguela Current, GIWA Regional assessment 44

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2005 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-940X

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and

in any form for educational or non-profi t purposes without

special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this

publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the

United Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2005. Prochazka, K., Davies, B., Griffi

ths, C., Hara, M.,

Luyeye, N., O'Toole, M., Bodenstein, J., Probyn, T., Clark, B., Earle,

A., Tapscott, C. and R. Hasler. Benguela Current, GIWA Regional

assessment 44. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and do not necessarily refl ect those of UNEP. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating

agencies concerning the legal status of any country, territory,

city or areas or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information

herein is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not

warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Contents

Executive summary

9

Abbreviations and acronyms

11

Regional defi nition

13

Boundaries of the region

13

Physical characteristics

15

Socio-economic characteristics

16

Assessment 19

Freshwater shortage

20

Pollution

25

Habitat and community modifi cation

30

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

35

Global change

40

Priority concerns for further analysis

43

Causal chain analysis

45

Freshwater shortage in the Orange-Vaal River Basin

45

Unsustainable exploitation of inshore fi nfi sh in the Benguela Current

48

Policy options

54

Addressing modifi cation of stream fl ow

54

Addressing unsustainable exploitation of inshore fi nfi sh resources

56

Conclusions and recommendations

58

References 60

Annexes 67

Annex I List of contributing authors and organisations

67

Annex II Detailed scoring tables

68

Annex III List of conventions and specifi c laws that aff ect water use in the region

73

Annex IV List of national policy and legislation

74

The Global International Waters Assessment

i

The GIWA methodology

vii

CONTENTS

Executive summary

The Benguela Current region (GIWA region 44) includes the entire

be the major contributor to Freshwater shortage in the region. Pollution

extent of the Benguela Current system and the freshwaters that drain

of freshwater resources through a number of avenues is also considered

into it. The region spans fi ve countries, including Angola, Namibia,

to be severe in the region, as are the impacts of changes in the water

Botswana, South Africa and Lesotho. The total coastline of the region

table due to overabstraction of aquifers with long replenishment times.

extends some 4 590 km from the Angolan enclave of Cabinda in the

Although some measures are in place to address the problems of

north to Cape Agulhas at the southern tip of the African continent. The

freshwater shortage in the region, the outlook for 2020 remains poor.

combined Exclusive Economic Zones of the three coastal states covers

some 1.9 million km2, with an estimated 1.4 million km2 falling within

Almost all forms of pollution of freshwater systems are assessed as

the Benguela Current region.

being severe, resulting in the overall assessment that the GIWA concern

Pollution is severe in the freshwater systems of the Benguela Current

The cold, northwards-fl owing Benguela Current system to a large extent

region. The primary issue of concern related to pollution of the marine

controls the climate of the region, which is for the most part arid or

environment is that of oil spills, which have profound environmental

semi-arid. The climate in turn infl uences the human dimensions of the

and economic impacts. Microbiological pollution, and pollution by solid

region, with the drier western areas being more sparsely populated than

waste are considered to be moderate, although highly localised, while

the wetter eastern parts. The region is characterised by high variability,

pollution by suspended solids as a result of marine mining activities is

both in natural processes such as rainfall and upwelling, and also in

also considered moderate but more diff use. The prognosis for 2020 is of

socio-economic processes, with the highly industrialised Gauteng

further deterioration of all types of pollution across the region.

Province of South Africa contrasting dramatically with subsistence-

based activities in Angola. The variability in the human dimensions

The modifi cation and loss of freshwater habitats and communities

translates into diff ering anthropogenic activities in diff erent parts of

of the Benguela Current region is assessed as severe. All major

the region, and hence into diff ering environmental impacts across the

freshwater habitats are considered to have undergone some form

region. A major diff erence in the environmental impacts is evident

of transformation, and much loss of habitats and ecosystems was

between the freshwater and marine systems of the region, and these

also evident. In the marine environment, modifi cation and loss of

systems were therefore assessed separately.

ecosystems and habitats is assessed as moderate. Of particular concern

are coastal lagoons, estuaries and mangroves. The projection for the

Environmental impacts surrounding the unsustainable use of

future is that habitats and communities within the Benguela Current

freshwater resources are severe in the region, while the impacts of this

region will continue to be transformed, and that further losses of

environmental degradation on the social and economic dimensions

habitats and ecosystems will occur.

are considered moderate to severe. This, together with the backdrop

of the natural aridity of the area, resulted in the GIWA concern of

Due to a low level of activity related to freshwater fi sheries in the

Freshwater shortage being highlighted as a priority for further analysis.

Benguela Current region, and the overwhelming importance of

Modifi cation of stream fl ow through the construction of dams and the

marine fi sheries, the GIWA concern of Unsustainable exploitation

overabstraction of water for agriculture and industry was considered to

of fi sh and other living resources was assessed only in the marine

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

9

environment. Overall the impacts of the concern are assessed as

through dam construction and overabstraction of water as immediate

being moderate in the region. Overexploitation was by far the most

causes of the environmental impacts. Root causes of this issue include

important contributing issue, with stocks of many marine resources

political decisions such as prioritisation of industrial water use, lack

being considered overexploited at present, and with resultant declines

of coordination among departments, demographic considerations,

in catches having been documented. As a general overview, it would

economic policies, and improvements in technology, particularly

appear as if the larger commercial fi sheries are more sustainably

irrigation technology. A suite of policy options for addressing these

managed at present, than are the smaller, and particularly the artisanal,

root causes was developed. This revolved around the three thematic

fi sheries. The future outlook is of sustainable commercial fi sheries, but

areas of changing the way water is perceived and used, eff ecting holistic

of a worsening of the current unsustainable exploitation in the smaller

planning, and improving existing management of water resources.

and less valuable fi sheries by 2020.

The case study of Unsustainable exploitation of inshore fi nfi sh in the

The impacts of the GIWA concern of Global change are assessed as

Benguela Current transboundary system highlighted overexploitation

moderate in freshwater systems and slight in marine systems. The

due to excessive fi shing eff ort and degradation of critical habitats

assessment of global change should be treated with some caution,

such as estuaries and mangroves as immediate causes of the

as this is an area where data are not readily available. Thus, in several

environmental impacts. The root causes of these were identifi ed as

cases, although impacts may currently exist, no direct evidence could

political encouragement of small-scale fi sheries, governance failures

be found for these, and it is thus likely that the assessment may have

and diffi

culty of regulation of inshore fi nfi sh fi sheries, a number of

underestimated the impacts. The environmental and socio-economic

economic considerations, improved capture technology, and poor

impacts of all issues related to Global change are expected to worsen

voluntary compliance. A suite of policy options was developed to

by 2020.

address the root causes of overexploitation around the two major

themes of reducing access to the fi sheries and improving voluntary

Two case studies were selected for more in-depth analysis of the root

compliance with existing regulations. A suite of three thematic options

causes of environmental degradation, and for analysis of policy options

was developed to address the root causes of degradation of critical

to address these. The two case studies were selected so as to represent

habitats, including introduction of holistic management of these

both the freshwater and marine environments of the Benguela Current

habitats, creation of alternative economic activities in coastal areas,

region. The case study of Freshwater shortage in the Orange-Vaal

and improved voluntary compliance with existing regulations.

transboundary river system highlighted modifi cation of stream fl ow

10

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 44 BENGUELA CURRENT

Abbreviations and acronyms

BCLME

Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Programme

CFCs Chlorofl

uorocarbons

CIA

Central Intelligence Agency (USA)

CPUE Catch

Per

Unit

Eff ort

CSIR

Council for Scientifi c and Industrial Research (South Africa)

DDT Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

DWAF

Department of Water Aff airs and Forestry (South Africa)

EEZ Exclusive

Economic

Zone

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization (United Nations)

GCM

Global Climate Model

GDP Gross

Domestic

Product

GEO Global

Environment

Outlook

GGP

Gross Geographic Product

GIWA

Global International Waters Assessment

GPS

Global Positioning System

IPCC

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

IUCN The

World

Conservation

Union

LORMS

Lower Orange River Management Study

MARPOL

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships

NCAR

National Centre for Atmospheric Research (USA)

ORASECOM Orange Senqu River Commission

PBMR Pebble

Bed

Modular

Reactor

Ramsar

Convention on Wetlands of International Importance

SADC Southern

African

Development

Community

SEAFO

South East Atlantic Fisheries Organization

SST Sea

Surface

Temperature

TAC Total

Allowable

Catch

UN United

Nations

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

USEPA

United States Environmental Protection Agency

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

11

List of figures

Figure 1

Boundaries of the Benguela Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Figure 2

Land cover in the Benguela Current. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Figure 3

Humidity in the Benguela Current.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Figure 4

Population density in the Benguela Current region.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Figure 5

Alien aquatic vegetation spreads rapidly and choke waterways, Western Cape, South Africa. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Figure 6

African penguins at Boulder's Beach, Simontown, South Africa. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Figure 7

Dry river beds are a common feature in the arid Benguela Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Figure 8

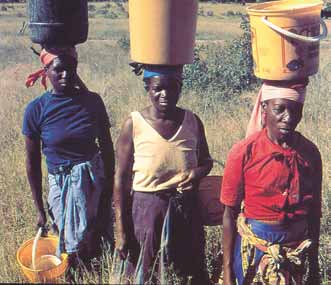

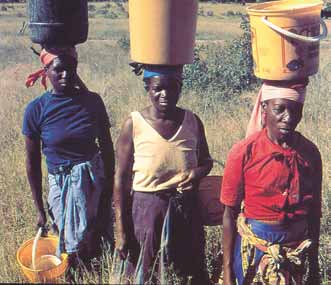

Women collecting water. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Figure 9

Fishing vessels in Hout Bay, South Africa. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Figure 10

Drakensberg mountains at the border between South Africa and Lesotho. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Figure 11

Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for freshwater shortage in the Orange-Vaal River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Figure 12

Beach seines used by traditional fishermen, False Bay, South Africa. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Figure 13

Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for unsustainable exploitation of inshore finfish in the Benguela Current. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Figure 14

Trawling in the Benguela Current. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

List of tables

Table 1

Geographical characteristics of the coastal countries in the Benguela Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Table 2

Socio-economic characteristics for the Benguela Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Table 3

GDP by sectors in Angola 2001. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Table 4

GDP by sectors in Namibia 2003. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Table 5

GDP by sectors in South Africa 2003. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Table 6

GDP by sector in Lesotho 2003. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Table 7

Scoring tables for the Benguela Current region.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Table 8

Rainfall and evaporation in the Benguela Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Table 9

Water availability and consumption in the southern African countries. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Table 10

Water use by sector in Namibia. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Table 11

Organic water pollution in the Benguela Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Table 12

The 20 largest tanker oil spills in the world. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Table 13

Condition of estuaries in South Africa's cool temperate biogeographic province. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Table 14

Overall score for the five GIWA concerns in the Benguela Current region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Table 15

Water demand from the Orange River by sectors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

List of boxes

Box 1

Climate models. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 44 BENGUELA CURRENT

Regional defi nition

This section describes the boundaries and the main physical and

water from this catchment, and for this reason is considered as part of

socio-economic characteristics of the region in order to defi ne the

the region. The country of Lesotho is also included within the region as

area considered in the regional GIWA Assessment and to provide

it falls entirely within the Orange-Vaal drainage basin. The region does

suffi

cient background information to establish the context within

not include the rivers draining off the eastern escarpment of South

which the assessment was conducted.

Africa, nor the rivers draining onto the south coast of the country, as

these are included in the Agulhas Current region. The easternmost

boundary on the landward side is at Cape Agulhas.

Boundaries of the region

For the purposes of this assessment, the oceanic boundary of the

region is taken as the limit of the 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic

The Benguela Current region (GIWA region 44) includes the entire

Zone (EEZ). Use of the 200 nautical mile EEZ as a boundary delimiter is

extent of the Benguela Current system and the freshwaters that drain

partially as a matter of convenience, but also to ensure that all economic

into it. The northern boundary extends to include Cabinda, a province

activity associated with the transboundary waters of the Benguela

of Angola which is entirely enclosed within the Democratic Republic of

Current region are included in the assessment. For the convenience

the Congo, and which represents the most northerly infl uence of the

of this assessment, the northern boundary is considered as a line

Benguela Current system on the marine environment and the socio-

drawn from the northernmost landward point (the northern tip of

economic climate (Figure 1).

Cabinda Province) and extending out to the 200 nautical mile limit. In

the southeast the region includes the entire Agulhas Bank as there is

Further landward, the region includes most of the western parts

signifi cant biological interaction between the Agulhas Bank and the

of Angola. The rivers draining into the Congo Basin are specifi cally

Benguela Current, and this area is thus of transboundary signifi cance

excluded from this region, as they are being dealt with as part of

within the Benguela Current region.

the Congo Basin in the Guinea Current region (GIWA region 42). Also

included in the region is most of Namibia, with the exception of the

A number of aquatic systems within the region are regarded as

rivers that drain into the Okavango system, as the Okavango is being

international waters due to their transboundary linkages, and their

considered as a discrete system within the Agulhas Current region

locations are marked on the map (Figure 1). The Benguela Current

(GIWA region 45a). The boundary of the region extends east to include

system itself forms part of the South Atlantic gyre system, and fl ows

the hyper-arid southwestern parts of Botswana. Since this includes

northwards along the west coast of southern Africa, from South Africa

such a small area of the country, Botswana will not be discussed in any

to Namibia and Angola. This system is transboundary by its very

detail in this report. Within South Africa the region includes the entire

nature, and a large proportion of the associated living resources are

catchment of the Orange-Vaal drainage basin, and thus includes the

shared across the entire system, and hence between the three coastal

large and industrialised urban centres of Johannesburg and Pretoria.

countries. To the south of the region, the Agulhas Bank, which falls

Although not strictly falling within the boundaries of the Orange-Vaal

entirely within the South African portion of the region, nevertheless has

Basin, the Gauteng Province is nevertheless an important recipient of

transboundary signifi cance, as there are strong biological interactions

REGIONAL DEFINITION

13

Elevation/

Depth (m)

4 000

2 000

Luanda Lagoon

1 000

Luanda

500

Cuanza

100

0

Cua

nza

-50

Angola

-200

-1 000

-2 000

C

u

n

e

ne

Baia dos Tigres

Cunene

Walvis Bay

Sandwich Harbour

Botswana

Namibia

Pretoria

Johannesburg

Vaal

South Africa

Orange

O

O

lif

ra

Lesotho

a

n

n

g

t

e

s

Groot-Berg

Langebaan Lagoon

Cape Town

0

500 Kilometres

© GIWA 2005

Figure 1

Boundaries of the Benguela Current region.

with transboundary implications between the Agulhas Bank and the

currently runs along the northern (Namibian) bank of the river, a

Benguela Current.

situation which results in constant confl ict between the two countries

regarding "ownership" and use of the River. In a region where water is

Two major transboundary river systems are identifi ed within the

scarce, the transboundary implications of these shared watercourses

region. These include the Cunene River, which runs along the national

are profound.

border between Namibia and Angola, and the Orange-Vaal drainage

system. The Orange-Vaal system contains several transboundary

Five estuaries in the region are considered to be of transboundary

features. Lesotho, entirely enclosed within South Africa, falls entirely

signifi cance. These include the Berg River Estuary (South Africa), the

within the drainage basin of this system, and is the source of several

Olifants River Estuary (South Africa), the Orange River Mouth (South

of the tributaries of this system. This system has further transboundary

Africa and Namibia), the Cunene River Mouth (Namibia and Angola),

signifi cance in that the Orange River runs in part along the national

and the Cuanza River Mouth (Angola). These estuaries provide nursery

border between South Africa and Namibia. The geo-political boundary

areas for a number of fi sh stocks which are shared between the coastal

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 44 BENGUELA CURRENT

countries of the region, and are thus of transboundary signifi cance

is even lower, reaching only less than 50 mm annually. The Namib

within the region. The transboundary signifi cance of these estuaries is,

Desert extends into southern Angola, and rainfall in this country ranges

however, even more geographically far-reaching, as they provide critical

from less than 50 mm in the south to approximately 300 mm/year in

feeding grounds for migratory palearctic wading birds.

the wetter northern coastal areas around the capital of Luanda (Encarta

2004). Rainfall on the coastal plain is characterised by high inter-annual

In addition to the estuaries, fi ve coastal lagoons in the region are

variability. This low rainfall results in desert and semi-desert conditions

considered of transboundary importance. These include Langebaan

on the coastal plains. Vegetation is generally sparse and low, and

Lagoon (South Africa), Sandwich Harbour and Walvis Bay Lagoon

adapted to xeric conditions (Figure 2). There is almost no natural

(Namibia), and Baia dos Tigres and the Luanda Lagoon (Angola). The

standing water on the coastal plains. Few permanent rivers traverse

primary justifi cation for including these as transboundary waters is

the coastal plains to enter the Benguela Current, and those that do have

that they support large numbers of palearctic migratory birds which

their origins in the wetter escarpment and/or plateau regions.

use these as feeding grounds during their non-breeding seasons.

Five ephemeral pans were also considered to be of transboundary

Landcover type

importance, as they provide important feeding areas for both Greater

Barren

Cropland

Luanda

and Lesser Flamingos, which are inter-African migrants. These include

Forest

Cuanza

Developed

Rocher Pan, Wadrif and Brandvlei pans in South Africa, and Sossusvlei

Grassland

z

a

na

Tundra

and Etosha pans in Namibia.

Angola

u

C

K

Wetland

unen

Savanna

e

Shrubland

Unclassified

Kunene

Water

Physical characteristics

Namibia

Botswana

The Benguela Current region is characterised by the presence of fl at

Pretoria

Johannesburg

coastal plains ranging in width from approximately 50 to 150 km. Further

Vaal

Oran

O

O

inland, the coastal plains rise abruptly up a mountainous escarpment

ge

lif

ra

a

n

n

Lesotho

g

South Afritsca

e

to an inland plateau with an average elevation of between 1 000 and

Groot-Berg

1 500 m (Encarta 2004).

Cape Town

© GIWA 2005

The Benguela Current is one of the world's four major coastal upwelling

Figure 2

Land cover in the Benguela Current.

systems (BCLME 1999). This highly productive, cold-water system is

(Source: based on USGS 2002)

bounded at both its northern and southern extremities by warm-water

systems (BCLME 1999). To the south the Benguela interacts with the warm

A mountainous escarpment rises from the coastal plain to the plateau.

Agulhas Current, and to the north with the Angola Current at the Angola/

On the plateau, average annual rainfall is in the region of 200 to 600 mm,

Benguela Front which typically migrates between 14° and 17° S on a

decreasing dramatically along an east-west gradient (Encarta 2004).

seasonal basis. The northern extremity of this interaction is approximately

Much of the plateau area falling within the Benguela Current region is

at the northern border of Angola (Hampton et al. 1998). Upwelling in the

arid and/or desert, including the Karoo basins of South Africa, and the

Benguela reaches its greatest intensity near Lüderitz in southern Namibia,

Kalahari Basin which spans South Africa, Botswana and Namibia (none

but a number of smaller upwelling cells are also recognised.

of the plateau areas of Angola are represented in the Benguela Current

region). The major permanent and transboundary rivers of the region,

The climate of the region is infl uenced primarily by the cold, northwards-

including the Cuanza River, Cunene River, Orange River and Vaal River,

fl owing Benguela Current, and the geo-morphology. Onshore air fl ow

arise in the wetter easterly areas of the plateau (Figure 3).

accumulates little moisture from the cold Benguela Current. The coastal

plains consequently receive very little rainfall and are arid or semi-arid.

The coastline of the region is highly exposed to wave action from

South Africa's western coastal plains, which constitute approximately

the prevailing southwesterly, wind-driven swells of the Benguela

21% of the country's land area, receive less than 200 mm of rainfall

Current, and few natural sheltered bays exist. Where these are present

annually (Encarta 2004). In Namibia, rainfall in the coastal Namib Desert

(including, but not exclusively, False Bay, Table Bay and Saldanha Bay in

REGIONAL DEFINITION

15

Socio-economic characteristics

Humidity

Humid

Dry sub-humid

The Benguela Current region contains four countries, including Angola,

Hyper-arid

Luanda

Namibia, South Africa and Lesotho. Each of these countries has distinct

Arid

Cuanza

Semi-arid

socio-economic characteristics, and the countries are thus presented

Lobito

Benguela

e

Baia Farta

individually. The population density in the region is shown in Figure 4.

nen

u

C

Angola

Cunene

Luanda

Namibia

Cuanza

Botswana

Swakopmund

Windhoek

z

a

n

Angola

a

uC

Pretoria

Cun

Lüderitz

e

Johannesburg

ne

l

Vaa

Orange

O

Cunene

ran

Lesotho

g

South Africa

e

GrootOli-fBeantrgs

Cape Town

A g u l h a s

B a n k

Namibia

BotswanaPretoria

© GIWA 2005

Johannesburg

Figure 3

Humidity in the Benguela Current.

Vaal

Population density

(Source: Deichmann & Eklundh 1991)

Orang

O

e

O

l

(persons/km2)

if

ra

a

n

n

Lesotho

g

<1

South Afritsca

e

1-2

South Africa, Lüderitz and Walvis Bay in Namibia, and Namibe in Angola)

Gro

3-5

ot-Berg

6-10

they act as nodes for urban development. The south is characterised

11-100

Cape Town

>100

by alternating rocky shore and sandy beaches, giving way to almost

ü GIWA 2005

entirely sandy shore in Namibia and along the Angolan coast. Along the

Figure 4

Population density in the Benguela Current region.

(Source: ORNL 2003)

coast of the Namib Desert, the combination of wave and wind-action

results in migrating sand-spits which form unstable sheltered bays or

lagoons, of which Walvis Bay in Namibia is an example.

Angola

The socio-economic climate of Angola has for the past 30 years been

The three coastal countries of the Benguela Current region have an

heavily infl uenced by continual civil war since its independence from

estimated total coastline of some 6 030 km, and EEZ of 1.9 million km2.

Portugal in 1975. The long-standing civil war had profound negative

Assuming that approximately half of the coastline and EEZ of South

eff ects on all aspects of human life in Angola, and this legacy continues.

Africa fall within the region results in the estimated total coastline of

Approximately 6 million people live in the coastal area (UNEP 2005).

the region being 4 590 km, and the EEZ being 1.4 million km2 in extent

Populations of the three cities of Lobito, Benguela and Baia Farta, situated

(Table 1).

on the coast, trebled in the 20 years between 1970 and 1990, while the

population in Namibe in the south more than doubled in just six years

between 1984 and 1990 (UNEP 2005). The capital city of Luanda, situated

Table 1

Geographical characteristics of the coastal countries in

on the coast, is home to some 20% of the estimated total population

the Benguela Current region.

of 13.7 million people (SADC 2003). The portion of the country that lies

Coastline

Continental shelf

EEZ

Country

(km)

(km2)

(km2)

within the Benguela Current region houses approximately 48% of the

Angola

1 650

51 000

330 000

total population (Table 2). Population density is 11 people/km2. Of the

Namibia

1 500

111 000

504 000

four countries in the region, Angola has the highest population growth

South Africa

2 880

143 400

1 050 000

rate at 1.97%, and the lowest literacy rate, estimated at only 40%. The

Total for the countries

6 030

305 400

1 884 000

population consists primarily of Africans (75%), with small portions of

Total for the Benguela Current region *

4 590

233 700

1 359 000

the population being made up of Europeans (1%), people of mixed

Note: * The estimated total for the Benguela Current region includes the entire coastline,

African and European background (2%), and others (22%) (CIA 2003). In

continental shelf and EEZs of Angola and Namibia, and half of each of these for South Africa.

(Source: SADC 2002)

addition to the indigenous population, Angola also provides a haven

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 44 BENGUELA CURRENT

Table 2

Socio-economic characteristics for the Benguela Current region.

Population in the Population in the

Population of

Population

Population

Country area

Urbanisation

Literacy rate

GDP per capita

Country

country

region

the country in

growth

density

(km2)

(%)

(%)

(USD)

(million)

(million)

the region (%)

(%)

(people/km2)

Angola

13.7

6.6

48

2.0

1 247 000

11

ND

40

656

Namibia

1.9

0.6

32

1.5

842 269

2

27

76

1 667

South Africa

44.9

15.5

34

0

1 221 000

37

30

82.2

3 714

Lesotho

2.2

1.8

80

0.2

30 355

72

17

78

368

Note: ND=No Data.

(Source: SADC 2003, CIA 2003, Landscan 2001)

Table 3

GDP by sectors in

to refugees from its neighbouring

Being largely a desert country,

Table 4

GDP by sectors in

Angola 2001.

country, the Democratic Republic

water is an important resource

Namibia 2003.

Sector

GDP (%)

of the Congo. At the same time,

for Namibia. Namibia has no

Sector

GDP (%)

Oil and gas

54

many Angolans live as refugees

permanent rivers entirely

Government services

21

Trade and commerce

15

in neighbouring states.

her own - all are shared with

Taxes less subsidies

13

Non-tradable services

10

neighbouring countries (UNEP

Manufacturing

11

Agriculture, forestry and fishing

8

The economy of Angola has been

2005). Not surprisingly, there

Wholesale and retail trade

10

Diamonds

6

severely disrupted by 30 years of

are currently several water-

Real estate and business services

9

Manufacturing

4

civil war, and GDP per capita is

related disputes between

Transport and communications

8

estimated at 656 USD (Table 2).

Namibia and her neighbours.

Construction

3

Mining and quarrying

7

(Source: SADC 2005)

By far the largest contributor to

There is currently some

Agriculture and forestry

5

the economy is the production

dispute between Namibia

Fishing and fish processing on board

4

of oil and gas off the coast, contributing 54% of the total GDP in 2001

and Botswana over the

Construction

3

(Table 3). Agriculture, forestry and fi shing contributed 8% in 2001, and of

construction of the Okavango

Financial intermediation

3

total agricultural production, fi sheries accounts for only a few percent,

hydroelectric scheme at Popa

Electricity and water

2

and is thus not an important component of the Angolan economy

Falls, with Angola over the

Other

2

(SADC 2003, 2005).

construction of an additional

Hotels and restaurants

2

dam on the Cunene River

Private and community services

<1

Namibia

which forms a boundary

(Source: SADC 2005)

Namibia is primarily a desert country, and has the lowest population

between these countries,

density (2 people/km2) of the four countries within the Benguela

and with South Africa regarding the exact location of the boundary

Current region (Table 2). An estimated 27% of the total population

between the two countries in the Orange River. There are also ongoing

of 1.9 million people live in urban centres, with some 10% of the

discussions between Namibia and South Africa regarding the exact

population residing within the capital city of Windhoek (SADC 2003). An

location of the boundary between their maritime zones.

estimated 32% of the total population resides within the area defi ned by

the Benguela Current region. The literacy rate is estimated at 76%. The

South Africa

population consists primarily of Africans (87.5%), with small portions of

South Africa has an interesting socio-economic history, having recently

the population being made up of Europeans (6%), and people of mixed

become free of the apartheid regime which eff ectively excluded the

African and European background (6.5%) (CIA 2003). Namibia gained

majority of the population from being active, participating citizens.

independence from South Africa in 1990.

Since the change to democracy in 1994, many reforms have taken place

in attempts to normalise the country. These reforms are still taking place

Namibia has a relatively diverse economy that does not rely heavily

and South Africa can still be considered a country in transition.

on only one sector as does that of Angola. Fishing and fi sh processing

contribute a total of 4% to the GDP (Table 4). GDP per capita is estimated

Of the four countries in the region, South Africa has the largest

at 1 667 USD (Table 2).

population, estimated at 44.9 million people of which 15.5 million

in the region (Table 2). The population is spread over an area of

REGIONAL DEFINITION

17

1.2 million km2, resulting in a population density of 37 people/km2.

region, 72 people/km2 (Table

2). Table 6

GDP by sector in

Lesotho 2003.

Urbanisation is estimated at 30%. Of the urbanised population,

Almost the entire population

Sector

GDP (%)

approximately half reside in the two major coastal cities of Cape Town

lives within the catchment of

Government and services

33

and Durban, while the other half reside in the two major cities of Pretoria

the Orange-Vaal drainage basin.

and Johannesburg, located within the catchment of the Orange-Vaal

Urbanisation is estimated at

Manufacturing 18

drainage basin (SADC 2003). Population growth is low, at only 0.01%.

17%, with only 7% of the total

Agriculture

17

This fi gure includes an adjustment made for the eff ects of early deaths

population (or 150

000

people)

Building and construction

17

caused by the severe HIV/AIDS situation in the country. The literacy rate

living in the capital and major city

Wholesale and retail trade

8

is relatively high, at 82.2%. The population consists primarily of Africans

of Maseru (SADC 2003). The literacy

Electricity and water

6

(75.2%), with smaller proportions of the population being made up of

rate is relatively high, at 78%. The

Mining and quarrying

<1

(Source: SADC 2005)

Europeans (13.6%), people of mixed African and European background

population consists almost entirely

(8.6%), and Asians (2.6%) (CIA 2003).

of Africans of the Sotho nation

(99.7%), with the remaining 0.3% being made up by Europeans, Asians

South Africa has the strongest and most diverse economy of the four

and others (CIA 2003).

countries in the Benguela Current region. GDP per capita is estimated

at 3 714 USD (Table 2), and a number of sectors contribute to the GDP

The economy of Lesotho has experienced some setbacks in the last

(Table 5). Agriculture, forestry and fi shing contribute a total of 4% to

decade due to civil unrest since its return to democracy in 1993. The

the GDP. Fisheries are largely marine, producing an estimated 600 000

situation does, however, appear to have stabilised over the last few

tonnes of fi sh each year, and

years, and the nation is working to rebuild its economy and to reduce

Table 5

GDP by sectors in

South Africa 2003.

employing some 27

000 poverty. GDP per capita is the lowest of the four countries in the

Sector

GDP (%)

people (SADC 2003, 2005).

Benguela Current region, estimated at 368 USD (Table 2). One of the

Manufacturing

20

largest contributors to the GDP in 2003, and previous years, was the

Much of South Africa is arid

building and construction sector (Table 6), much of which is related to

Finance, real estate, business activities

20

and semi-arid, and water is

the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (SADC 2005).

Trade, hotels and restaurants

14

thus an important natural

General government

13

resource. Not surprisingly,

International agreements, national policy and

Transport and communications

12

there are several water-

legal frameworks

Mining and quarrying

5

related disputes between

A number of international agreements relating to the environment

Agriculture, forestry and fishing

4

South Africa and its and its protection are in place in countries within the Benguela Current

Electricity, gas and water

3

neighbours as mentioned

region (Annex III). There are also substantial national policies and legal

Construction

3

above. There are also disputes

frameworks aimed at protection of the natural environment in place

Imputed financial service charges

3

within the country over water

in these countries (Annex IV). This national legislation covers broad

Other producers

3

(Source: SADC 2005)

resources.

issues surrounding healthy and unpolluted natural environments,

water and sanitation, but also covers more specifi c issues such as

Lesotho

the exploitation and management of fi sh and other living resources,

Lesotho is the smallest country within the Benguela Current region,

mandatory environmental impact assessment, and protection of the

and is totally surrounded by South Africa. The total estimated

environment from pollution, oil and gas exploration and exploitation,

population of 2.2 million people live within and area of 30 355 km2,

and mining activities.

resulting in the highest population density of the four countries in the

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 44 BENGUELA CURRENT

Assessment

This section presents the results of the assessment of the impacts of each of the fi ve predefi ned GIWA concerns i.e. Freshwater shortage,

Pollution, Habitat and community modifi cation, Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources, Global change, and

their constituent issues and the priorities identifi ed during this process. The evaluation of severity of each issue adheres to a set of

predefi ned criteria as provided in the chapter describing the GIWA methodology. In this section, the scoring of GIWA concerns and

issues is presented in Table 7.

Table 7

Scoring tables for the Benguela Current region.

T

T

C

C

Increased impact

A 0 No

known

impact

A

2 Moderate

impact

Assessment of GIWA concerns and issues according

The arrow indicates the likely

IMP

IMP

T

T

No changes

C

C

to scoring criteria (see Methodology chapter).

direction of future changes.

A 1 Slight

impact

A

3 Severe

impact

IMP

IMP

Decreased impact

a

c

t

s

i

t

y

i

t

y

n

a

c

t

s

n

Benguela Current

t

a

l

p

*

*

p

*

*

a

c

t

s

u

t

a

l

a

c

t

s

u

e

n

p

m

Benguela Current

e

n

p

m

m

i

c

i

m

m

m

o

Score

m

i

c

i

m

o

Score

Freshwater component

n

i

m

y

*

*

*

n

i

m

y

*

*

*

c

t

s

m

m

o

c

t

s

Marine component

c

t

s

o

c

t

s

v

i

r

o

n

e

r c

n

e

r c

o

a

l

t

h

a

l

t

h

t

h

erall

v

i

r

o

o

t

h

erall

En

impa

Ec

He

O

impa

Ov

Priorit

En

impa

Ec

He

O

impa

Ov

Priorit

Freshwater shortage

3*

3

2

2

2.5

1

Pollution

2*

3

2

1

2.3

2

Modification of stream flow

3

Microbiological pollution

2

Pollution of existing supplies

3

Eutrophication

1

Changes in the water table

3

Chemical

1

Pollution

3*

3

2

1

2.5

2

Suspended solids

2

Solid waste

2

Microbiological pollution

3

Thermal 1

Eutrophication

3

Radionuclides

1

Chemical

3

Spills

3

Suspended solids

2

Solid waste

3

Habitat and community modification

2*

2

2

2

2.3

2

Thermal 1

Loss of ecosystems

1

Radionuclides

3

Modification of ecosystems

2

Spills

3

Unsustainable exploitation of fish

2*

2

2

2

2.1

1

Habitat and community modification

3*

2

2

2

2.4

2

Overexploitation

3

Loss of ecosystems

3

Excessive by-catch and discards

1

Modification of ecosystems

3

Destructive fishing practices

2

Global change

2*

0

1

0

1.4

2

Decreased viability of stock

0

Impact on biological and genetic diversity

2

Changes in hydrological cycle

2

Sea level change

-

Global change

1*

0

1

0

1.3

2

Increased UV-B radiation

2

Changes in hydrological cycle

2

Changes in ocean CO source/sink function

-

Sea level change

1

2

Increased UV-B radiation

0

*

This value represents an average weighted score of the environmental issues associated

to the concern.

Changes in ocean CO source/sink function

1

2

** This value represents the overall score including environmental, socio-economic and

likely future impacts.

*** Priority refers to the ranking of GIWA concerns.

ASSESSMENT

19

The enormous diversity of the Benguela Current region adds an

Table 8

Rainfall and evaporation in the Benguela Current region.

additional level of complexity to an assessment which attempts to

Rainfall

Deficit/Gain

Country

(mm/year)

Evaporation

provide a general view for the region as a whole. No justifi cation

(mm/year)

(mm/year)

Average

Range

could be found for treating any of the transboundary aquatic systems

Angola

800

25-1 600

1 300-2 600

-1 275 to -1 000

identifi ed as systems entirely discrete from the other transboundary

Lesotho

700

500-2 000

1 800-2 100

-1 300 to -100

aquatic systems of the region. The assessment for the Benguela

Namibia

250

10-700

2 600-3 700

-3 000 to -2 590

Current region was thus conducted on the entire region. This did

South Africa

500

50-3 000

1 100-3 000

-1 050 to 0

serve to create some confusion within the assessment process, and

Note: Deficit/Gain indicates the discrepancy between rainfall and evaporation. Please note that

these figures are for entire countries, not only for the portions of these countries falling within the

the impacts of an issue would often be entirely opposite within the

Benguela Current region.

two diff erent aquatic components (freshwater and marine systems) of

(Source: Snaddon et al. 1999)

the region, or would vary enormously from place to place. The GIWA

guidance of presenting the worst case scenario for an issue was used

basin transfers. This has caused dramatic changes to the fl ow and

throughout the assessment. In many cases, of course, the worst case

fl ood regimes of many rivers in the region and their related estuaries.

scenario does not necessarily hold true for the entire region. Under

The coast is also strongly infl uenced by the rivers that bring water,

these circumstances, justifi cation has been provided for the worst

sediments, nutrients and pollutants to the coast. One of the most

case scenario without necessarily indicating every example in which

important threats to estuaries is the reduction of freshwater infl ow as

this does not hold true. In order to illustrate this, an assessment of

the result of the construction of dams and direct abstraction of water.

severe pollution from spills into the marine environment, for example,

does not indicate that the entire marine environment of the region is

Total water available in South Africa equates to about 50 km3/year,

permanently covered in oil pollution. It does, however, indicate that the

approximately 10% of the water reserves of the southern African

environmental, economic, health and social impacts of spills, which may

region. Currently, about 84% of total available water is in use (Table 9)

vary temporally and spatially within the region, are severe.

(Snaddon et al. 1999, Conley 1995). The annual water defi cit may

reach an estimated 1 050 mm/year (Heyns et al. 1994, Snaddon et al.

The large diff erences in the environmental and socio-economic issues

1999). There is a high inter-annual variability in rainfall (Davies & Day

occurring in marine and freshwater environments in the Benguela

1998). In Namibia, total water available equates to about 9 km3/year,

Current region lead to the concerns of Pollution, Habitat modifi cation

approximately 2% of the southern African total (Snaddon et al. 1999,

and Global change being assessed separately for these environments.

Since freshwater fi sheries are not highly signifi cant in the region, these

Table 9

Water availability and consumption in the southern

were omitted, and the assessments are thus only concerned with

African countries.

Total water

Share of total

unsustainable exploitation of marine living resources.

Share of southern

Total water use

Country

available

available water

African water (%)

(million m3/year)

(million m3)

used (%)

Angola *

158 000

32

480

2

Zambia

96 000

19

360

2

Freshwater shortage

Tanzania

76 000

15

480

2

Mozambique

58 000

11

760

3

T

C

A

South Africa *

50 000

10

19 040

84

IMP

Freshwater component

Zimbabwe

23 000

5

1 220

5

The climate over much of southern Africa ranges from semi-arid to

Namibia *

9 000

2

ND

ND

hyper-arid with only a few relatively humid parts where rainfall greatly

Botswana

9 000

2

90

<1

exceeds 500 mm annually (Davies & Day 1998). Over the Benguela

Malawi

9 000

2

160

1

Current region evaporation is high, exceeding the limited and highly

Swaziland

7 000

1

ND

ND

variable rainfall (Table 8). The naturally low and variable rainfall, together

Lesotho *

4 000

1

50

<1

with the water demand of an increasing population and the related

Total

499 000

100

22 640

100

demand for freshwater caused by industrialisation, agriculture and

Notes: ND = No Data.

urbanisation has led to radical modifi cations of available surface and

* Countries within the Benguela Current region. Please note that these figures are for entire

countries, not only for those portions falling within the Benguela Current region.

groundwater in the form of impoundments, abstraction and inter-

(Source: Snaddon et al. 1999)

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 44 BENGUELA CURRENT

Conley 1995). Evaporation is high and Namibia's Eastern National

Orange-Vaal system

Water Carrier, for example, which is an open canal (Omatako Canal

The Orange-Vaal drainage basin is 1 million km2 (Department of Water

Inter-basin Transfer) evaporates 70% of water in transit (Petitjean &

Aff airs and Forestry 2005) and by far the largest catchment in the region.

Davies 1988). The resultant water defi cit due to evaporative losses

A clear trend of decreasing fl ow has been shown in the Orange River

for this country is in the region of 2 590 to 3 000 mm/year (Heyns et

between 1935 and 1997 such that annual fl ow gaugings towards the

al. 1994, Snaddon et al. 1999). The only permanent rivers of Namibia

end of this period are less than 50% of those at the beginning of this

which fall within the Benguela Current region are the Cunene River

time series (Department of Environmental Aff airs and Tourism 2000).

(north) and the Orange River (south), both of which are transnational

In the Orange-Vaal drainage system fl ows are modifi ed by turbines

boundaries. The remaining of Van Der Kloof Dam (originally PK Le Roux Dam) to the extent that

Table 10

Water use by

rivers are all ephemeral. There

seasonal diff erences of fl ow entering Gariep Reservoir (originally HF

sector in Namibia.

is thus a strong reliance on

Verwoerd Dam) upstream are nullifi ed (54% in summer, 46% in winter)

Sector

Water use (%)

groundwater and inter-basin (Cambray et al. 1986, Davies & Bergh 1999). The Vaal River has 16

transfers. Reservoirs suff er

major dams, while inter-basin transfer schemes from the Orange River

Irrigation

49

vast evaporative losses (Agula

(Senqu, Senquenyane and Malibamatso in Lesotho), Tugela, Usutu and

Urban (all inclusive)

24

2002). Namibia's water supply

Komati augment the supply to this river. Water is also exported from

Livestock

15

can thus be considered critical.

the Vaal River through inter-basin transfers to the Limpopo, Olifants

Major damage has been done

and Komati rivers. Together with the Orange River the Vaal River is the

Mining

7

to ephemeral rivers of Namibia

most modifi ed river in the Southern African Development Community

Rural domestic

5

(Heyns et al. 1988, Jacobsen et al.

(SADC) region (Braune & Rogers 1987).

Wildlife and tourism

<1

1995). The largest sectoral water

(Source: International Rivers Network 2004)

user in Namibia is irrigation

In the Vaal system in the late 1980s, the return fl ows from the urban/

(Table 10).

industrial sector were already 55% of supply, thereby exceeding the

natural mean annual run-off of 300 million m3/year (Braune & Rogers

Total water available in Angola is about 158 km3/year, approximately

1987). Drought in the early 1980s led to construction of pump/barrages

32% of the total water available in southern Africa. The proportion of

reversing the fl ow of the Vaal River. These barrages washed away during

total available water in use is about 2% (Conley 1995, Snaddon et al.

later fl oods. This scheme was known as the Grootdraai Emergency

1999). Water defi cit due to evaporative losses is in the region of 1 000

Augmentation Scheme (1983). Completed in 20 weeks, it involved seven

to 1 275 mm/year (Heyns et al. 1994, Snaddon et al. 1999). Total water

earth compacted weirs and pumps, and covered 208 km of reversed

available in Lesotho is estimated at 4 km3/year, roughly 1% of southern

fl ow to Grootdraai Dam. In 1987 an additional pipeline was constructed

Africa's available water. Total annual water usage is approximately 0.2%

for emergency supplies of coolant water to coal-fi red power stations in

of the total available (Conley 1995, Snaddon et al. 1999). Evaporation

Gauteng (Department of Water Aff airs and Forestry 1991).

exceeds rainfall, leading to a water defi cit of between 100 and 1 300

mm/year (Heyns et al. 1994, Snaddon et al. 1999).

Inter-basin transfers from the headwaters of the Orange River in Lesotho

to the Vaal River will reduce the yield of the Orange River Project (inter-

Environmental impacts

basin transfer from Lake Gariep to the Fish and Sundays rivers in the

Modifi cation of stream fl ow

Eastern Cape) by more than 1.5 km3/year, whilst doubling the yield of

The environmental impacts of modifi cation of stream fl ow are assessed

the Vaal River (Davies et al. 1993). Completion of the Lesotho Highlands

as severe in the region. Many rivers in the region are modifi ed by

Water Project will result in 75% of the water in the Vaal River being

impoundments and many are overabstracted, resulting in a signifi cant

derived from other catchments (Snaddon et al. 1999). The Orange-

decrease in river fl ow. Up to a 75% reduction in stream fl ow has been

Vaal system contributes 22% of South Africa's water resources, but

recorded, this being in the Berg River, one of the few permanently

has no overarching basin authority (Cambray et al. 1986, Davies &

open estuaries in the region (Berg 1993). The key river systems of

Bergh 1999).

transboundary signifi cance in the region include the Orange-Vaal

system, Berg River, Olifants River, Cunene River and Cuanza River. A

Berg River

brief description of the extent to which each has been modifi ed (with

Historical fl ow fi gures for the Berg River for 1928 to 1988 show periods

the exception of the Cuanza River) is provided below.

of reductions in stream fl ow return of >75% due to human abstractions.

ASSESSMENT

21

The Berg River had a mean annual run-off to the estuary of 903 million

been highlighted as a hotspot of freshwater fi sh diversity in South Africa

m3/year compared to the present day fi gure of 693 million m3/year,

(Skelton 1993). It supports 10 indigenous fi sh species of which eight

which represents a 23% mean annual reduction. Flows in all months

are endemic to the system. Intensifi cation of agricultural activity in the

are aff ected, but summer losses are particularly signifi cant for the

catchment has precipitated alteration to the fl ow regime of the river

biota (Berg 1993, Ninham Shand Inc. 1992). The previously mobile

though, and to some geomorphological degradation. These eff ects,

Berg River Estuary Mouth was moved and hardened in 1966, changing

as well as those caused by populations of alien fi sh being introduced

tidal amplitude and resulting in higher seawater intrusion onto the

into the catchment in the 1930s and 1940s, have been implicated in

fl oodplain. Impoundments prolong river low fl ows, increasing salinity

the serious decline evident amongst indigenous fi sh species in the

intrusion and reducing sediment dynamics. The planned Skuifraam

Olifants River. The spread of alien fi sh is assisted by dams that have

Dam will reduce fl ushing and scouring, and lead to possible closure

been constructed in the mainstream of the river (Impson 1997). The

of the mouth (Huizinga et al. 1993, Morant et al. 1997). Berg River

dams represent impassable barriers to the migration of fi sh, and have

fl oodplain vegetation includes 10 diff erent communities, including

substantially increased the proportion of lentic and lotic conditions in

fi ve marsh types, two distinct pan communities, and three fl oodplain

the river, and altered the fl ow regime of the downstream reaches.

communities. It represents a unique system between southern Angola

and St Lucia in KwaZulu-Natal on the east coast of South Africa.

Cunene River

Impoundment and mouth entrainment are considered to be the most

The Cunene River is about 1 000 km long and has a drainage basin

serious threats to the community structure (McDowell 1993).

of about 106 500 km2. The surrounding environment of the river is

characterised by a dry climate, low rainfall, low annual run-off and low

Berg River Estuary benthic invertebrate communities have decreased over

sediment production. The river itself is already highly regulated through

the past 40 years. Major contributing factors and threats include reduced

various dams and weirs including the Gove Dam (completed in 1973),

fl ows, increased desiccation, increased salinities due to impoundment

the Matala weir (completed in 1954), the Calueque weir (completed in

and mouth entrainment, and possibly pollution (Hockey 1993). The Berg

1977) and the Ruacana hydropower station (completed in 1979). The

River estuarine fi sh communities contain 77% of total coastal species

Gove Dam was built with the purpose of downstream river regulation

(compared to 49-52% for other coastal areas). The Berg River has a higher

but has long since been in-operational because of war damages. The

percentage of residents (23% versus 4-18%), dependent species (27%

daily fl ow regime of the river has been substantially modifi ed as a

versus 9-25%) and partially dependent species (30% versus 18-27%) than

result of the Ruacana diversion weir and water abstraction, causing

other estuaries in the region. Flow reduction in this system will have more

daily water level fl uctuations of 30 to 40 cm at Epupa. Another scheme

impact on coastal fi sheries than anywhere else in South Africa. The Berg

has been proposed for the lower portion of the river, the Lower Cunene

River is one of only two permanently open estuarine nursery areas in the

Hydropower Scheme, and in spite of strong environmental opposition

Namaqua Marine Biogeographical Province (Bennett 1993). An important

may still come into being (Members of the GIWA Task team pers.

sports fi shery is developing on the estuary, but the commercial fi shery

comm.). Very little development exists in the Cunene catchment, and

is overexploited. This, together with increased salinity through reduced

the water is thus of exceptionally good quality.

fl ows, makes the industry no longer viable (Schrauwen 1993). 127 species

of birds have been recorded in the Berg River wetlands since 1975. In

The Cunene River has a diverse freshwater fi sh fauna consisting of

terms of regional importance, the Berg River fl oodplain rates second, only

64 species, seven of which are endemic to this system. The Ruacana

slightly lower than Walvis Bay, but above Langebaan Lagoon and St Lucia

and Epupa Falls form large physical obstructions but do not restrict

(KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa). In 1992, bird populations on the estuary

the distribution of species. Despite the alterations to the fl ow regime,

were estimated to number 46 000 individuals, including individuals from

sensitive fi sh species are still maintained, and the natural fl ow-related

fi ve IUCN Red Data species.

processes are still regarded as intact (NAMANG Consortium 1998). A

total of 379 bird species are recorded in the Lower Cunene, of which 62

Olifants River

are listed as IUCN Red Data species. The majority of these are breeding

The Olifants River drains a catchment of about 45 600 km2 making it

residents (62%).

the second largest river on the South African west coast. It is one of

the few perennial rivers in the arid western parts of South Africa. The

Pollution of existing supplies

Olifants River and estuary seldom dry up and therefore form one of

Of the three countries which make up the bulk of the region, South

the few perennial, calm waters areas in the region. The river itself has

Africa is by far the largest contributor to overall organic water pollution.

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 44 BENGUELA CURRENT

However, when this fi gure is converted to kilograms of emissions per

scheme), where the water table has dropped from between 0 and 5 m

worker per day, the highest fi gure is attributed to Namibia (World Bank

to between 10 and 11 m below river bed level (Petitjean & Davies 1988,

2001). Other pollution problems in the region's freshwater systems

Snaddon et al. 1999). Of further concern is the fact that ephemeral

include chemical pollution, solid waste, radionuclide pollution and

rivers and groundwater support 50% of Namibia's population across

spills. In the region as a whole, pollution of existing freshwater resources

80% of the country, placing enormous stress on water tables (Heyns

is considered severe.

et al. 1988).

The Vaal River in South Africa has severe pollution and eutropication

South Africa had an estimated 197 810 existing boreholes in 1999

problems. The problems stem from agricultural (155 000 ha under

(Department of Environmental Aff airs and Tourism 2000). An additional

irrigation in 1975 which equates to 42% of South African total agricultural

50 000 are estimated to be drilled annually, although the majority of

production), urban (sewage effl

uent; 42% of population in 1975) and

these yield little or no water (Department of Environmental Aff airs

mining (79% of mining production in 1975) return fl ows (Braune &

and Tourism 2000). Extraction of groundwater has increased from

Rogers 1987). Of the return fl ows to the Vaal Barrage (37 000 m3/day in

an estimated 1.8 to 2.0 km3/year in the past 20 years, with irrigation

the 1980s), about 75% is sewage effl

uent, 11% from industry, and 14%

agriculture accounting for approximately 78% of this usage (Department

mining effl

uent (Oliveira 1986).

of Environmental Aff airs and Tourism 2000). The cumulative impacts

of the extraction of groundwater can only be guessed at, although

In the early 1980s mine discharges to the Vaal River amounted to an

groundwater failure has been known to occur in some areas (Basson

average of 60 000 m3/day (Oliveira 1986). Intense mining in the Vaal

et al. 1997)

catchment has lead to salinities of 75 to 500 mS/m (Van Vliet 1986,

Viljoen & Van der Merwe 1986). Northern tributaries of the Vaal River

Socio-economic impacts

have elevated total dissolved solids (>500 mg/l) predominantly from

Economic impacts

Sulphate (SO ), Sodium (Na) and Chlorine (Cl) (Van Vliet 1986). Sulphuric

Most sectors are aff ected by freshwater shortages, including agriculture,

4

acid pollution is also evident in the Vaal drainage basin from acid mine

mining, fi shing, and tourism, in an area which is already water-stressed.

run-off (Harrison 1958, Davies et al. 1993).

The economic impacts of this concern are therefore considered severe

by the GIWA experts. The costs of building dams, inter-basin transfer

Impoundment of the Vaal River, eutrophication and injection of

schemes, alternative water sources (especially desalination plants), and

reservoir plankton has led to signifi cant increases in pest blackfl y

water treatment are high. There is a mismatch between the geography

species (Simuliidae) to epidemic proportions (Chutter 1963, 1967, 1968,

of supply and demand, which creates additional costs. In addition, in

De Moor 1982, 1986). Blindness in sheep (Chlamydia sp., protoctistan

the more arid parts of the region there is a mismatch between peak

parasite) and Rift Valley Fever (viral) are diseases commonly spread by

demand and supply (e.g. the major tourist season coincides with the

blackfl ies (De Moor 1986). DDT used in the Vaal River to control epidemic

driest time of year).

outbreaks during the 1960s led to eradication of the indigenous insect

fauna and rapid recolonisation by blackfl y larvae after use (Howell &

The major economic impacts of modifi cation of stream fl ow are

Holmes 1969).

the costs associated with the construction of dams and inter-basin

transfer schemes to supply water. The costs of alternative sources of

Changes in the water table

water (especially by desalination) are also high. Pollution results in

Impacts related to changes in the water table are considered severe

economic impacts related to the costs of treatment of polluted or

in the Benguela Current region. The problem revolves primarily

contaminated water, and the costs of alternative water supplies. The

around the use of fossil waters, which have long replenishment times.

economic impacts of changes in the water table revolve primarily

Overabstraction of aquifers, together with decreased base-fl ow of

around salination of the water. These include the expense of alternative

rivers to replenish supplies has resulted in exhaustion of aquifers and

supplies, loss of agricultural income and potential, increased costs to

subsequent salinisation.

industry of water treatment, costs of recycling, and in extreme cases