(1,1) -1- Cover 43_only.indd 2004-04-06, 09:19:17

Global International

Waters Assessment

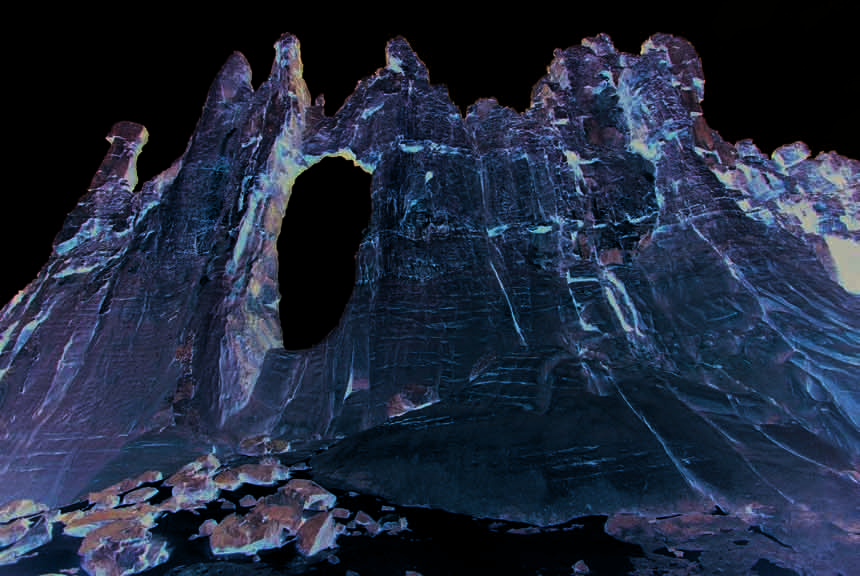

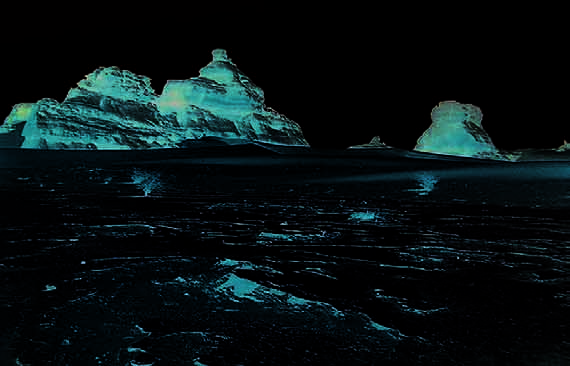

Lake Chad Basin

GIWA Regional assessment 43

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment 43

Lake Chad Basin

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Report editors: Matthew Fortnam, Johnson Oguntola

Editorial assistance: Johanna Egerup

Maps & GIS: Niklas Holmgren

Design & graphics: Joakim Palmqvist

Global International Waters Assessment

Lake Chad Basin, GIWA Regional assessment 43

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2004 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-9401

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and

in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without

special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this

publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the

United Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2004. Fortnam, M.P. and Oguntola, J.A. (eds), Lake Chad

Basin, GIWA Regional assessment 43, University of Kalmar, Kalmar,

Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and do not necessarily reflect those of UNEP. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating

agencies concerning the legal status of any country, territory,

city or areas or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information

herein is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not

warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Printed and bound in Sweden by Sunds Tryck Öland AB.

CONTENTS

vII

Contents

The Global International Waters Assessment

ix

The GIWA methodology

xv

Preface

1

Acknowledgements

2

Executive summary

4

Abbreviations and acronyms

9

Regional definition

13

Boundaries of the Lake Chad region

13

Physical characteristics

14

Socio-economic characteristics

28

Assessment

42

Freshwater shortage

42

Habitat and community modification

56

Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources

66

Pollution

70

Priority concerns

74

Causal chain analysis

79

Chari-Logone and Lake Chad sub-system

80

Komadugu-Yobe sub-system

88

Conclusions

95

Policy options

96

Problem definition

96

Lake Chad Basin

98

Chari-Logone/Lake Chad sub-system

100

Komadugu-Yobe sub-system

102

Identification of the recommended options

106

Conclusions and recommendations

116

References

119

Annexes

126

Annex I GIWA workshop participants.

126

Annex II Detailed scoring tables.

127

CONTENTS

vII

The Global International

Waters Assessment

This report presents the results of the Global International Waters

Adequately managing the world's aquatic resources for the benefit of

Assessment (GIWA) of the transboundary waters of the Lake Chad

al is, for a variety of reasons, a very complex task. The liquid state of

Basin. This and the subsequent chapter offer a background that

the most of the world's water means that, without the construction

describes the impetus behind the establishment of GIWA, its

of reservoirs, dams and canals it is free to flow wherever the laws of

objectives and how the GIWA was implemented.

nature dictate. Water is, therefore, a vector transporting not only a

wide variety of valuable resources but also problems from one area

to another. The effluents emanating from environmental y destructive

activities in upstream drainage areas are propagated downstream

The need for a global

and can affect other areas considerable distances away. In the case of

international waters

transboundary river basins, such as the Nile, Amazon and Niger, the

assessment

impacts are transported across national borders and can be observed

in the numerous countries situated within their catchments. In the case

of large oceanic currents, the impacts can even be propagated between

Global y, people are becoming increasingly aware of the degradation of

continents (AMAP 1998). Therefore, the inextricable linkages within

the world's water bodies. Disasters from floods and droughts, frequently

and between both freshwater and marine environments dictates that

reported in the media, are considered to be linked with ongoing global

management of aquatic resources ought to be implemented through

climate change (IPCC 2001), accidents involving large ships pol ute public

a drainage basin approach.

beaches and threaten marine life and almost every commercial fish stock

is exploited beyond sustainable limits - it is estimated that the global

In addition, there is growing appreciation of the incongruence

stocks of large predatory fish have declined to less that 10% of pre-

between the transboundary nature of many aquatic resources and the

industrial fishing levels (Myers & Worm 2003). Further, more than 1 bil ion

traditional introspective national y focused approaches to managing

people worldwide lack access to safe drinking water and 2 bil ion people

those resources. Water, unlike laws and management plans, does not

lack proper sanitation which causes approximately 4 billion cases of

respect national borders and, as a consequence, if future management

diarrhoea each year and results in the death of 2.2 mil ion people, mostly

of water and aquatic resources is to be successful, then a shift in focus

children younger than five (WHO-UNICEF 2002). Moreover, freshwater

towards international cooperation and intergovernmental agreements

and marine habitats are destroyed by infrastructure developments,

is required (UN 1972). Furthermore, the complexity of managing the

dams, roads, ports and human settlements (Brinson & Malvárez 2002,

world's water resources is exacerbated by the dependence of a great

Kennish 2002). As a consequence, there is growing public concern

variety of domestic and industrial activities on those resources. As a

regarding the declining quality and quantity of the world's aquatic

consequence, cross-sectoral multidisciplinary approaches that integrate

resources because of human activities, which has resulted in mounting

environmental, socio-economic and development aspects into

pressure on governments and decision makers to institute new and

management must be adopted. Unfortunately however, the scientific

innovative policies to manage those resources in a sustainable way

information or capacity within each discipline is often not available or

ensuring their availability for future generations.

is inadequately translated for use by managers, decision makers and

GLOBAL INTERNATIONAL WATERS ASSESSMENT

iX

policy developers. These inadequacies constitute a serious impediment

The Global Environment Facility (GEF)

to the implementation of urgently needed innovative policies.

The Global Environment Facility forges international co-operation and finances actions to address

six critical threats to the global environment: biodiversity loss, climate change, degradation of

international waters, ozone depletion, land degradation, and persistent organic pol utants (POPs).

Continual assessment of the prevailing and future threats to aquatic

The overal strategic thrust of GEF-funded international waters activities is to meet the incremental

ecosystems and their implications for human populations is essential if

costs of: (a) assisting groups of countries to better understand the environmental concerns of

their international waters and work col aboratively to address them; (b) building the capacity

governments and decision makers are going to be able to make strategic

of existing institutions to utilise a more comprehensive approach for addressing transboundary

policy and management decisions that promote the sustainable use of

water-related environmental concerns; and (c) implementing measures that address the priority

transboundary environmental concerns. The goal is to assist countries to utilise the full range of

those resources and respond to the growing concerns of the general

technical, economic, financial, regulatory, and institutional measures needed to operationalise

public. Although many assessments of aquatic resources are being

sustainable development strategies for international waters.

conducted by local, national, regional and international bodies, past

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

assessments have often concentrated on specific themes, such as

United Nations Environment Programme, established in 1972, is the voice for the environment

biodiversity or persistent toxic substances, or have focused only on

within the United Nations system. The mission of UNEP is to provide leadership and encourage

partnership in caring for the environment by inspiring, informing, and enabling nations and

marine or freshwaters. A globally coherent, drainage basin based

peoples to improve their quality of life without compromising that of future generations.

assessment that embraces the inextricable links between transboundary

UNEP work encompasses:

freshwater and marine systems, and between environmental and

Assessing global, regional and national environmental conditions and trends;

Developing international and national environmental instruments;

societal issues, has never been conducted previously.

Strengthening institutions for the wise management of the environment;

Facilitating the transfer of knowledge and technology for sustainable development;

Encouraging new partnerships and mind-sets within civil society and the private sector.

International call for action

University of Kalmar

University of Kalmar hosts the GIWA Co-ordination Office and provides scientific advice and

administrative and technical assistance to GIWA. University of Kalmar is situated on the coast of

The need for a holistic assessment of transboundary waters in order to

the Baltic Sea. The city has a long tradition of higher education; teachers and marine officers have

been educated in Kalmar since the middle of the 19th century. Today, natural science is a priority

respond to growing public concerns and provide advice to governments

area which gives Kalmar a unique educational and research profile compared with other smal er

and decision makers regarding the management of aquatic resources

universities in Sweden. Of particular relevance for GIWA is the established research in aquatic and

environmental science. Issues linked to the concept of sustainable development are implemented

was recognised by several international bodies focusing on the global

by the research programme Natural Resources Management and Agenda 21 Research School.

environment. In particular, the Global Environment Facility (GEF)

Since its establishment GIWA has grown to become an integral part of University activities.

The GIWA Co-ordination office and GIWA Core team are located at the Kalmarsund Laboratory, the

observed that the International Waters (IW) component of the GEF

university centre for water-related research. Senior scientists appointed by the University are actively

suffered from the lack of a global assessment which made it difficult

involved in the GIWA peer-review and steering groups. As a result of the cooperation the University

can offer courses and seminars related to GIWA objectives and international water issues.

to prioritise international water projects, particularly considering

the inadequate understanding of the nature and root causes of

environmental problems. In 1996, at its fourth meeting in Nairobi, the

causes of degradation of the transboundary aquatic environment and

GEF Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP), noted that: "Lack of

options for addressing them. These processes led to the development

an International Waters Assessment comparable with that of the IPCC, the

of the Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) that would be

Global Biodiversity Assessment, and the Stratospheric Ozone Assessment,

implemented by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in

was a unique and serious impediment to the implementation of the

conjunction with the University of Kalmar, Sweden, on behalf of the GEF.

International Waters Component of the GEF".

The GIWA was inaugurated in Kalmar in October 1999 by the Executive

Director of UNEP, Dr. Klaus Töpfer, and the late Swedish Minister of the

The urgent need for an assessment of the causes of environmental

Environment, Kjel Larsson. On this occasion Dr. Töpfer stated: "GIWA

degradation was also highlighted at the UN Special Session on

is the framework of UNEP´s global water assessment strategy and will

the Environment (UNGASS) in 1997, where commitments were

enable us to record and report on critical water resources for the planet for

made regarding the work of the UN Commission on Sustainable

consideration of sustainable development management practices as part of

Development (UNCSD) on freshwater in 1998 and seas in 1999. Also in

our responsibilities under Agenda 21 agreements of the Rio conference".

1997, two international Declarations, the Potomac Declaration: Towards

enhanced ocean security into the third mil ennium, and the Stockholm

The importance of the GIWA has been further underpinned by the UN

Statement on interaction of land activities, freshwater and enclosed

Mil ennium Development Goals adopted by the UN General Assembly

seas, specifical y emphasised the need for an investigation of the root

in 2000 and the Declaration from the World Summit on Sustainable

x

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

GLOBAL INTERNATIONAL WATERS ASSESSMENT

x I

Development in 2002. The development goals aimed to halve the

International waters and transboundary issues

proportion of people without access to safe drinking water and basic

The term "international waters", as used for the purposes of the GEF Operational Strategy,

sanitation by the year 2015 (United Nations Millennium Declaration

includes the oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed seas and estuaries, as

wel as rivers, lakes, groundwater systems, and wetlands with transboundary drainage basins

2000). The WSSD also cal s for integrated management of land, water and

or common borders. The water-related ecosystems associated with these waters are considered

living resources (WSSD 2002) and, by 2010, the Reykjavik Declaration on

integral parts of the systems.

Responsible Fisheries in the Marine Ecosystem should be implemented

The term "transboundary issues" is used to describe the threats to the aquatic environment

linked to globalisation, international trade, demographic changes and technological advancement,

by al countries that are party to the declaration (FAO 2001).

threats that are additional to those created through transboundary movement of water. Single

country policies and actions are inadequate in order to cope with these chal enges and this makes

them transboundary in nature.

The international waters area includes numerous international conventions, treaties, and

agreements. The architecture of marine agreements is especial y complex, and a large number

The conceptual framework

of bilateral and multilateral agreements exist for transboundary freshwater basins. Related

conventions and agreements in other areas increase the complexity. These initiatives provide

and objectives

a new opportunity for cooperating nations to link many different programmes and instruments

into regional comprehensive approaches to address international waters.

Considering the general decline in the condition of the world's aquatic

the large-scale deforestation of mangroves for ponds (Primavera 1997).

resources and the international y recognised need for a global y

Within the GIWA, these "non-hydrological" factors constitute as large

coherent assessment of transboundary waters, the primary objectives

a transboundary influence as more traditional y recognised problems,

of the GIWA are:

such as the construction of dams that regulate the flow of water into

To provide a prioritising mechanism that al ows the GEF to focus

a neighbouring country, and are considered equal y important. In

their resources so that they are used in the most cost effective

addition, the GIWA recognises the importance of hydrological units that

manner to achieve significant environmental benefits, at national,

would not normal y be considered transboundary but exert a significant

regional and global levels; and

influence on transboundary waters, such as the Yangtze River in China

To highlight areas in which governments can develop and

which discharges into the East China Sea (Daoji & Daler 2004) and the

implement strategic policies to reduce environmental degradation

Volga River in Russia which is largely responsible for the condition of

and improve the management of aquatic resources.

the Caspian Sea (Barannik et al. 2004). Furthermore, the GIWA is a truly

regional assessment that has incorporated data from a wide range of

In order to meet these objectives and address some of the current

sources and included expert knowledge and information from a wide

inadequacies in international aquatic resources management, the GIWA

range of sectors and from each country in the region. Therefore, the

has incorporated four essential elements into its design:

transboundary concept adopted by the GIWA extends to include

A broad transboundary approach that generates a truly regional

impacts caused by globalisation, international trade, demographic

perspective through the incorporation of expertise and existing

changes and technological advances and recognises the need for

information from al nations in the region and the assessment of

international cooperation to address them.

all factors that influence the aquatic resources of the region;

A drainage basin approach integrating freshwater and marine

systems;

The organisational structure and

A multidisciplinary approach integrating environmental and socio-

economic information and expertise; and

implementation of the GIWA

A coherent assessment that enables global comparison of the

results.

The scale of the assessment

Initial y, the scope of the GIWA was confined to transboundary waters

The GIWA builds on previous assessments implemented within the GEF

in areas that included countries eligible to receive funds from the GEF.

International Waters portfolio but has developed and adopted a broader

However, it was recognised that a truly global perspective would only

definition of transboundary waters to include factors that influence the

be achieved if industrialised, GEF-ineligible regions of the world were

quality and quantity of global aquatic resources. For example, due to

also assessed. Financial resources to assess the GEF-eligible countries

globalisation and international trade, the market for penaeid shrimps

were obtained primarily from the GEF (68%), the Swedish International

has widened and the prices soared. This, in turn, has encouraged

Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) (18%), and the Finnish

entrepreneurs in South East Asia to expand aquaculture resulting in

Department for International Development Cooperation (FINNIDA)

x

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

GLOBAL INTERNATIONAL WATERS ASSESSMENT

x I

1

15

11

16

14

12

28

10

13

25

17

29

9

18

19

30

23

22

8 6 7

31

20

24

26

35

33

2

34

27

5

21

50

32

51

36

37

41

52

4

49

53

43

65

55

3

48

54

42

56

46

62

47

40b

40a

57

62

45b

39

59

45a

58

60

64

44

61

38

63

66

1

Arctic

12

Norwegian Sea (LME)

24 Aral Sea

36 East-China Sea (LME)

46 Somali Coastal Current (LME)

58 North Australian Shelf (LME)

2

Gulf of Mexico (LME)

13

Faroe plateau

25 Gulf of Alaska (LME)

37

Hawaiian Archipelago (LME)

47

East African Rift Valley Lakes

59 Coral Sea Basin

3

Caribbean Sea (LME)

14

Iceland Shelf (LME)

26 California Current (LME)

38 Patagonian Shelf (LME)

48 Gulf of Aden

60 Great Barrier Reef (LME)

4

Caribbean Islands

15

East Greenland Shelf (LME)

27 Gulf of California (LME)

39 Brazil Current (LME)

49 Red Sea (LME)

61

Great Australian Bight

5

Southeast Shelf (LME)

16

West Greenland Shelf (LME)

28 East Bering Sea (LME)

40a Brazilian Northeast (LME)

50 The Gulf

62 Small Island States

6

Northeast Shelf (LME)

17

Baltic Sea (LME)

29 West Bering Sea (LME)

40b Amazon

51

Jordan

63 Tasman Sea

7

Scotian Shelf (LME)

18

North Sea (LME)

30 Sea of Okhotsk (LME)

41

Canary Current (LME)

52 Arabian Sea (LME)

64 Humboldt Current (LME)

8

Gulf of St Lawrence

19

Celtic-Biscay Shelf (LME)

31

Oyashio Current (LME)

42 Guinea Current (LME)

53 Bay of Bengal S.E.

65 Eastern Equatorial Pacific

9

Newfoundland Shelf (LME)

20 Iberian Coastal (LME)

32 Kuroshio Current (LME)

43 Lake Chad

54 South China Sea (LME)

66 Antarctic (LME)

10

Baffin Bay, Labrador Sea,

21

Mediterranean Sea (LME)

33 Sea of Japan/East Sea (LME)

44 Benguela Current (LME)

55 Mekong River

Canadian Archipelago

22 Black Sea (LME)

34 Yellow Sea (LME)

45a Agulhas Current (LME)

56 Sulu-Celebes Sea (LME)

11

Barents Sea (LME)

23 Caspian Sea

35 Bohai Sea

45b Indian Ocean Islands

57 Indonesian Seas (LME)

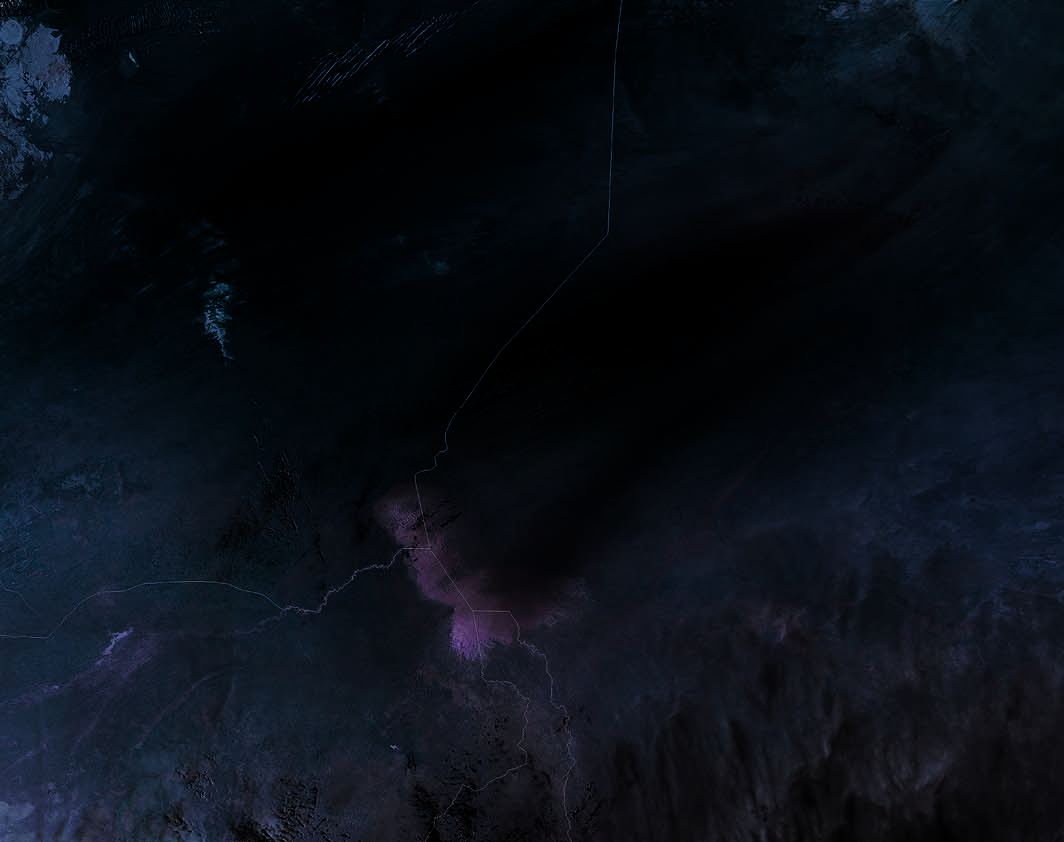

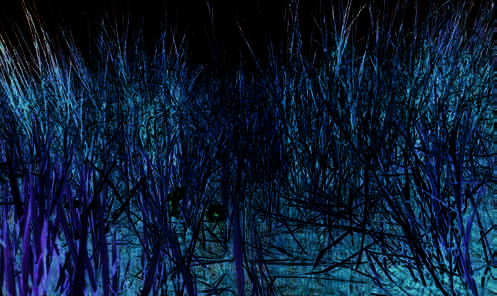

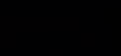

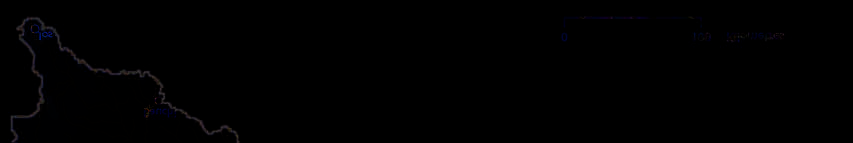

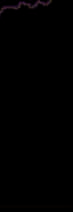

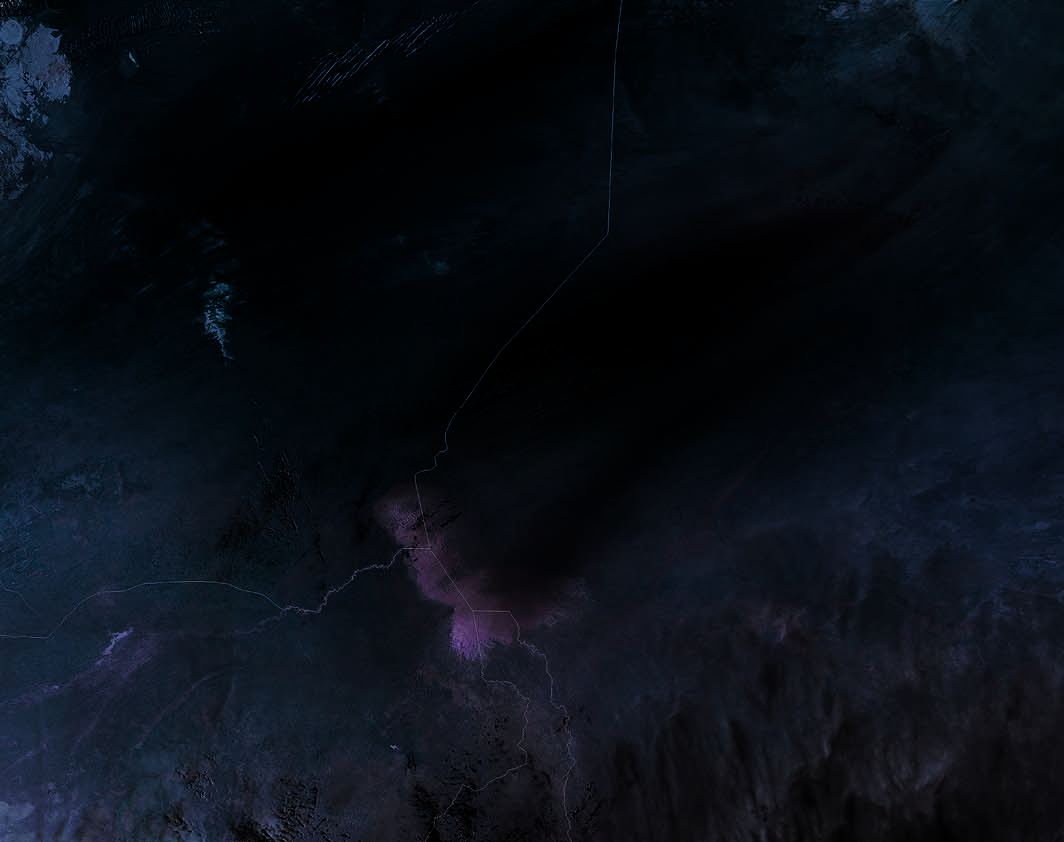

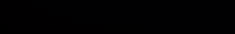

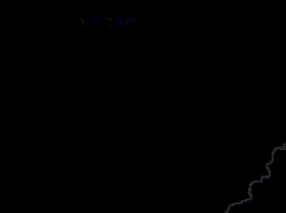

Figure 1

The 66 transboundary regions assessed within the GIWA project.

(10%). Other contributions were made by Kalmar Municipality, the

Considering the objectives of the GIWA and the elements incorporated

University of Kalmar and the Norwegian Government. The assessment of

into its design, a new methodology for the implementation of the

regions ineligible for GEF funds was conducted by various international

assessment was developed during the initial phase of the project. The

and national organisations as in-kind contributions to the GIWA.

methodology focuses on five major environmental concerns which

constitute the foundation of the GIWA assessment; Freshwater shortage,

In order to be consistent with the transboundary nature of many of the

Pol ution, Habitat and community modification, Overexploitation of fish

world's aquatic resources and the focus of the GIWA, the geographical

and other living resources, and Global change. The GIWA methodology

units being assessed have been designed according to the watersheds

is outlined in the fol owing chapter.

of discrete hydrographic systems rather than political borders (Figure 1).

The geographic units of the assessment were determined during the

The global network

preparatory phase of the project and resulted in the division of the

In each of the 66 regions, the assessment is conducted by a team of

world into 66 regions defined by the entire area of one or more

local experts that is headed by a Focal Point (Figure 2). The Focal Point

catchments areas that drains into a single designated marine system.

can be an individual, institution or organisation that has been selected

These marine systems often correspond to Large Marine Ecosystems

on the basis of their scientific reputation and experience implementing

(LMEs) (Sherman 1994, IOC 2002).

international assessment projects. The Focal Point is responsible

for assembling members of the team and ensuring that it has the

Large Marine Ecocsystems (LMEs)

necessary expertise and experience in a variety of environmental

Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) are regions of ocean space encompassing coastal areas from river

and socio-economic disciplines to successful y conduct the regional

basins and estuaries to the seaward boundaries of continental shelves and the outer margin of the

major current systems. They are relatively large regions on the order of 200 000 km2 or greater,

assessment. The selection of team members is one of the most critical

characterised by distinct: (1) bathymetry, (2) hydrography, (3) productivity, and (4) trophical y

elements for the success of GIWA and, in order to ensure that the

dependent populations.

The Large Marine Ecosystems strategy is a global effort for the assessment and management

most relevant information is incorporated into the assessment, team

of international coastal waters. It developed in direct response to a declaration at the 1992

members were selected from a wide variety of institutions such as

Rio Summit. As part of the strategy, the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have joined in an action program to assist developing

universities, research institutes, government agencies, and the private

countries in planning and implementing an ecosystem-based strategy that is focused on LMEs as

sector. In addition, in order to ensure that the assessment produces a

the principal assessment and management units for coastal ocean resources. The LME concept is

also adopted by GEF that recommends the use of LMEs and their contributing freshwater basins

truly regional perspective, the teams should include representatives

as the geographic area for integrating changes in sectoral economic activities.

from each country that shares the region.

x II

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

GLOBAL INTERNATIONAL WATERS ASSESSMENT

x III

The GIWA is comprised of a logical sequence of four integrated

components. The first stage of the GIWA is cal ed Scaling and is a

process by which the geographic area examined in the assessment is

defined and al the transboundary waters within that area are identified.

Once the geographic scale of the assessment has been defined, the

assessment teams conduct a process known as Scoping in which the

magnitude of environmental and associated socio-economic impacts

of Freshwater shortage, Pol ution, Habitat and community modification,

Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources, and Global

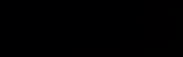

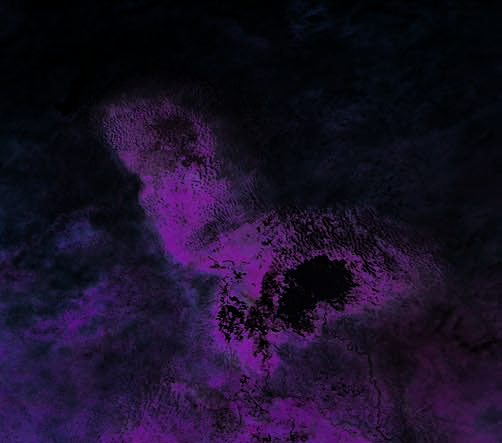

Figure 2

The organisation of the GIWA project.

change is assessed in order to identify and prioritise the concerns

that require the most urgent intervention. The assessment of these

predefined concerns incorporates the best available information and

In total, more than 1 000 experts have contributed to the implementation

the knowledge and experience of the multidisciplinary, multi-national

of the GIWA il ustrating that the GIWA is a participatory exercise that

assessment teams formed in each region. Once the priority concerns

relies on regional expertise. This participatory approach is essential

have been identified, the root causes of these concerns are identified

because it instils a sense of local ownership of the project, which

during the third component of the GIWA, Causal chain analysis. The root

ensures the credibility of the findings and moreover, it has created a

causes are determined through a sequential process that identifies, in

global network of experts and institutions that can col aborate and

turn, the most significant immediate causes fol owed by the economic

exchange experiences and expertise to help mitigate the continued

sectors that are primarily responsible for the immediate causes and

degradation of the world's aquatic resources.

final y, the societal root causes. At each stage in the Causal chain

analysis, the most significant contributors are identified through an

analysis of the best available information which is augmented by the

expertise of the assessment team. The final component of the GIWA is

GIWA Regional reports

the development of Policy options that focus on mitigating the impacts

of the root causes identified by the Causal chain analysis.

The GIWA was established in response to growing concern among the

general public regarding the quality of the world's aquatic resources

The results of the GIWA assessment in each region are reported in

and the recognition of governments and the international community

regional reports that are published by UNEP. These reports are designed

concerning the absence of a global y coherent international waters

to provide a brief physical and socio-economic description of the

assessment. However, because a holistic, region-by-region, assessment

most important features of the region against which the results of the

of the condition of the world's transboundary water resources had never

assessment can be cast. The remaining sections of the report present

been undertaken, a methodology guiding the implementation of such

the results of each stage of the assessment in an easily digestible form.

an assessment did not exist. Therefore, in order to implement the GIWA,

Each regional report is reviewed by at least two independent external

a new methodology that adopted a multidisciplinary, multi-sectoral,

reviewers in order to ensure the scientific validity and applicability of

multi-national approach was developed and is now available for the

each report. The 66 regional assessments of the GIWA will serve UNEP

implementation of future international assessments of aquatic resources.

as an essential complement to the UNEP Water Policy and Strategy and

UNEP's activities in the hydrosphere.

UNEP Water Policy and Strategy

The primary goals of the UNEP water policy and strategy are:

(a) Achieving greater global understanding of freshwater, coastal and marine environments by

conducting environmental assessments in priority areas;

Global International Waters Assessment

(b) Raising awareness of the importance and consequences of unsustainable water use;

(c) Supporting the efforts of Governments in the preparation and implementation of integrated

management of freshwater systems and their related coastal and marine environments;

(d) Providing support for the preparation of integrated management plans and programmes for

aquatic environmental hot spots, based on the assessment results;

(e) Promoting the application by stakeholders of precautionary, preventive and anticipatory

approaches.

x II

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

GLOBAL INTERNATIONAL WATERS ASSESSMENT

x III

References:

AMAP (1998). Assessment Report: Arctic Pol ution Issues. Arctic

Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Oslo, Norway.

Barannik, V., Borysova, O. and Stolberg, F. (2004). The Caspian Sea Region:

Environmental Change. Ambio, 33:45-51.

Brinson, M.M. and Malvárez, A.I. (2002). Temperate freshwater wetlands:

types, status, and threats. Environmental Conservation, 29:115-133.

Daoji, L. and Daler, D. (2004). Ocean Pol ution from Land-based Sources:

East China Sea, China. Ambio, 33:98-106.

FAO (2001). Reykjavik conference on responsible fisheries in the marine

ecosystem. Iceland, 1-4 October 2001.

IOC (2002). IOC-IUCN-NOAA Consultative Meeting on Large Marine

Ecosystems (LMEs). Fourth Session, 8-9 January 2002, Paris,

France.

IPCC (2001). Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution

of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Houghton,

J.T., Ding, Y., Griggs, D.J., Noguer, M., van der Linden, P.J., Dai, X.,

Maskel , K. and Johnson, C.A. (eds). Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

Kennish, M.J. (2002). Environmental threats and environmental future of

estuaries. Environmental Conservation, 29:78-107.

Myers, R.A. and Worm, B. (2003). Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory

fish communities. Nature, 423:280-283.

Primavera, J.H. (1997) Socio-economic impacts of shrimp culture.

Aquaculture Research, 28:815-827.

Sherman, K. (1994). Sustainability, biomass yields, and health of coastal

ecosystems: an ecological perspective. Marine Ecology Progress

Series, 112:277-301.

United Nations conference on the human environment (1972). Report

available on-line at http://www.unep.org

United Nations Mil ennium Declaration (2000). The Mil ennium

Assembly of the United Nations, New York.

WHO-UNICEF (2002). Global Water Supply and Sanitation Assessment:

2000 Report.

WSSD (2002). World Summit on Sustainable Development.

Johannesburg Summit 2002. Key Outcomes of the Summit,

UN Department of Public Information, New York.

x IV

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

The GIWA methodology

The specific objectives of the GIWA were to conduct a holistic and global y

The assessment integrates environmental and socio-economic data

comparable assessment of the world's transboundary aquatic resources

from each country in the region to determine the severity of the

that incorporated both environmental and socio-economic factors

impacts of each of the five concerns and their constituent issues on

and recognised the inextricable links between freshwater and marine

the entire region. The integration of this information was facilitated by

environments, in order to enable the GEF to focus their resources and to

implementing the assessment during two participatory workshops

provide guidance and advice to governments and decision makers. The

that typical y involved 10 to 15 environmental and socio-economic

coalition of al these elements into a single coherent methodology that

experts from each country in the region. During these workshops, the

produces an assessment that achieves each of these objectives had not

regional teams performed preliminary analyses based on the col ective

previously been done and posed a significant chal enge.

knowledge and experience of these local experts. The results of these

analyses were substantiated with the best available information to be

The integration of each of these elements into the GIWA methodology

presented in a regional report.

was achieved through an iterative process guided by a special y

Table 1

Pre-defined GIWA concerns and their constituent issues

convened Methods task team that was comprised of a number of

addressed within the assessment.

international assessment and water experts. Before the final version

of the methodology was adopted, preliminary versions underwent

Environmental issues

Major concerns

an extensive external peer review and were subjected to preliminary

1. Modification of stream flow

testing in selected regions. Advice obtained from the Methods task

2. Pol ution of existing supplies

I Freshwater shortage

team and other international experts and the lessons learnt from

3. Changes in the water table

preliminary testing were incorporated into the final version that was

4. Microbiological

5. Eutrophication

used to conduct each of the GIWA regional assessments.

6. Chemical

7. Suspended solids

II Pollution

8. Solid wastes

Considering the enormous differences between regions in terms of the

9. Thermal

10. Radionuclide

quality, quantity and availability of data, socio-economic setting and

11. Spil s

environmental conditions, the achievement of global comparability

12. Loss of ecosystems

required an innovative approach. This was facilitated by focusing

III Habitat and community

13. Modification of ecosystems or ecotones, including community

modification

the assessment on the impacts of five pre-defined concerns namely;

structure and/or species composition

Freshwater shortage, Pollution, Habitat and community modification,

14. Overexploitation

15. Excessive by-catch and discards

IV Unsustainable

Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources and Global

16. Destructive fishing practices

exploitation of fish and

change, in transboundary waters. Considering the diverse range of

17. Decreased viability of stock through pol ution and disease

other living resources

18. Impact on biological and genetic diversity

elements encompassed by each concern, assessing the magnitude of

the impacts caused by these concerns was facilitated by evaluating the

19. Changes in hydrological cycle

20. Sea level change

V Global change

impacts of 22 specific issues that were grouped within these concerns

21. Increased uv-b radiation as a result of ozone depletion

22. Changes in ocean CO source/sink function

(see Table 1).

2

THE GIWA METHODOLOGY

vii

political boundaries but were instead, general y defi ned by a large but

discrete drainage basin that also included the coastal marine waters into

which the basin discharges. In many cases, the marine areas examined

during the assessment coincided with the Large Marine Ecosystems

(LMEs) defi ned by the US National Atmospheric and Oceanographic

Administration (NOAA). As a consequence, scaling should be a

relatively straight-forward task that involves the inspection of the

boundaries that were proposed for the region during the preparatory

phase of GIWA to ensure that they are appropriate and that there are

no important overlaps or gaps with neighbouring regions. When the

proposed boundaries were found to be inadequate, the boundaries of

the region were revised according to the recommendations of experts

from both within the region and from adjacent regions so as to ensure

that any changes did not result in the exclusion of areas from the GIWA.

Once the regional boundary was defi ned, regional teams identifi ed all

the transboundary elements of the aquatic environment within the

region and determined if these elements could be assessed as a single

Figure 1

Illustration of the relationship between the GIWA

coherent aquatic system or if there were two or more independent

approach and other projects implemented within the

GEF International Waters (IW) portfolio.

systems that should be assessed separately.

The GIWA is a logical contiguous process that defi nes the geographic

Scoping Assessing the GIWA concerns

region to be assessed, identifi es and prioritises particularly problems

Scoping is an assessment of the severity of environmental and socio-

based on the magnitude of their impacts on the environment and

economic impacts caused by each of the fi ve pre-defi ned GIWA concerns

human societies in the region, determines the root causes of those

and their constituent issues (Table 1). It is not designed to provide an

problems and, fi nal y, assesses various policy options that addresses

exhaustive review of water-related problems that exist within each region,

those root causes in order to reverse negative trends in the condition

but rather it is a mechanism to identify the most urgent problems in the

of the aquatic environment. These four steps, referred to as Scaling,

region and prioritise those for remedial actions. The priorities determined

Scoping, Causal chain analysis and Policy options analysis, are

by Scoping are therefore one of the main outputs of the GIWA project.

summarised below and are described in their entirety in two volumes:

GIWA Methodology Stage 1: Scaling and Scoping; and GIWA Methodology:

Focusing the assessment on pre-defi ned concerns and issues ensured

Detailed Assessment, Causal Chain Analysis and Policy Options Analysis.

the comparability of the results between diff erent regions. In addition, to

General y, the components of the GIWA methodology are aligned

ensure the long-term applicability of the options that are developed to

with the framework adopted by the GEF for Transboundary Diagnostic

mitigate these problems, Scoping not only assesses the current impacts

Analyses (TDAs) and Strategic Action Programmes (SAPs) (Figure 1) and

of these concerns and issues but also the probable future impacts

assume a broad spectrum of transboundary infl uences in addition to

according to the "most likely scenario" which considered demographic,

those associated with the physical movement of water across national

economic, technological and other relevant changes that wil potential y

borders.

infl uence the aquatic environment within the region by 2020.

Scaling Defining the geographic extent

The magnitude of the impacts caused by each issue on the

of the region

environment and socio-economic indicators was assessed over the

Scaling is the fi rst stage of the assessment and is the process by which

entire region using the best available information from a wide range of

the geographic scale of the assessment is defi ned. In order to facilitate

sources and the knowledge and experience of the each of the experts

the implementation of the GIWA, the globe was divided during the

comprising the regional team. In order to enhance the comparability

design phase of the project into 66 contiguous regions. Considering the

of the assessment between diff erent regions and remove biases

transboundary nature of many aquatic resources and the transboundary

in the assessment caused by diff erent perceptions of and ways to

focus of the GIWA, the boundaries of the regions did not comply with

communicate the severity of impacts caused by particular issues, the

viii

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

THE GIWA METHODOLOGY

ix

results were distil ed and reported as standardised scores according to

Table 2

Example of environmental impact assessment of

the fol owing four point scale:

Freshwater shortage.

Weight

0 = no known impact

Environmental

Environmental issues

Score

Weight %

averaged

concerns

1 = slight impact

score

2 = moderate impact

1. Modification of stream flow

1

20

Freshwater shortage

1.50

3 = severe impact

2. Pol ution of existing supplies

2

50

The attributes of each score for each issue were described by a detailed

3. Changes in the water table

1

30

set of pre-defined criteria that were used to guide experts in reporting

Table 3

Example of Health impacts assessment linked to one of

the results of the assessment. For example, the criterion for assigning

the GIWA concerns.

a score of 3 to the issue Loss of ecosystems or ecotones is: "Permanent

Criteria for Health impacts

Raw score

Score Weight %

destruction of at least one habitat is occurring such as to have reduced their

Very small

Very large

surface area by >30% during the last 2-3 decades". The full list of criteria is

Number of people affected

2

50

0

1

2

3

presented at the end of the chapter, Table 5a-e. Although the scoring

Minimum

Severe

Degree of severity

2

30

0

1

2

3

inevitably includes an arbitrary component, the use of predefined

Occasion/Short

Continuous

Frequency/Duration

2

20

criteria facilitates comparison of impacts on a global scale and also

0

1

2

3

Weight average score for Health impacts

2

encouraged consensus of opinion among experts.

The trade-off associated with assessing the impacts of each concern

After al 22 issues and associated socio-economic impacts have

and their constituent issues at the scale of the entire region is that spatial

been scored, weighted and averaged, the magnitude of likely future

resolution was sometimes low. Although the assessment provides a

changes in the environmental and socio-economic impacts of each

score indicating the severity of impacts of a particular issue or concern

of the five concerns on the entire region is assessed according to the

on the entire region, it does not mean that the entire region suffers

most likely scenario which describes the demographic, economic,

the impacts of that problem. For example, eutrophication could be

technological and other relevant changes that might influence the

identified as a severe problem in a region, but this does not imply that all

aquatic environment within the region by 2020.

waters in the region suffer from severe eutrophication. It simply means

that when the degree of eutrophication, the size of the area affected,

In order to prioritise among GIWA concerns within the region and

the socio-economic impacts and the number of people affected is

identify those that will be subjected to causal chain and policy options

considered, the magnitude of the overal impacts meets the criteria

analysis in the subsequent stages of the GIWA, the present and future

defining a severe problem and that a regional action should be initiated

scores of the environmental and socio-economic impacts of each

in order to mitigate the impacts of the problem.

concern are tabulated and an overall score calculated. In the example

presented in Table 4, the scoping assessment indicated that concern I I,

When each issue has been scored, it was weighted according to the relative

Habitat and community modification, was the priority concern in this

contribution it made to the overal environmental impacts of the concern

region. The outcome of this mathematic process was reconciled against

and a weighted average score for each of the five concerns was calculated

the knowledge of experts and the best available information in order

(Table 2). Of course, if each issue was deemed to make equal contributions,

to ensure the validity of the conclusion.

then the score describing the overal impacts of the concern was simply the

arithmetic mean of the scores al ocated to each issue within the concern.

In some cases however, this process and the subsequent participatory

In addition, the socio-economic impacts of each of the five major

discussion did not yield consensus among the regional experts

concerns were assessed for the entire region. The socio-economic

regarding the ranking of priorities. As a consequence, further analysis

impacts were grouped into three categories; Economic impacts,

was required. In such cases, expert teams continued by assessing the

Health impacts and Other social and community impacts (Table 3). For

relative importance of present and potential future impacts and assign

each category, an evaluation of the size, degree and frequency of the

weights to each. Afterwards, the teams assign weights indicating the

impact was performed and, once completed, a weighted average score

relative contribution made by environmental and socio-economic

describing the overal socio-economic impacts of each concern was

factors to the overal impacts of the concern. The weighted average

calculated in the same manner as the overall environmental score.

score for each concern is then recalculated taking into account

viii

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

THE GIWA METHODOLOGY

ix

Table 4

Example of comparative environmental and socio-economic impacts of each major concern, presently and likely in year 2020.

Types of impacts

Environmental score

Economic score

Human health score

Social and community score

Concern

Overall score

Present (a)

Future (b)

Present (c)

Future (d)

Present (e)

Future (f)

Present (g)

Future (h)

Freshwater shortage

1.3

2.3

2.7

2.8

2.6

3.0

1.8

2.2

2.3

Pol ution

1.5

2.0

2.0

2.3

1.8

2.3

2.0

2.3

2.0

Habitat and community

2.0

3.0

2.4

3.0

2.4

2.8

2.3

2.7

2.6

modification

Unsustainable exploitation of fish

1.8

2.2

2.0

2.1

2.0

2.1

2.4

2.5

2.1

and other living resources

Global change

0.8

1.0

1.5

1.7

1.5

1.5

1.0

1.0

1.2

the relative contributions of both present and future impacts and

should be regarded as a framework to guide the analysis, rather than

environmental and socio-economic factors. The outcome of these

as a set of detailed instructions. Secondly, in an ideal setting, a causal

additional analyses was subjected to further discussion to identify

chain would be produced by a multidisciplinary group of specialists

overall priorities for the region.

that would statistical y examine each successive cause and study its

links to the problem and to other causes. However, this approach (even

Final y, the assessment recognises that each of the five GIWA concerns

if feasible) would use far more resources and time than those available

are not discrete but often interact. For example, pollution can destroy

to GIWA1. For this reason, it has been necessary to develop a relatively

aquatic habitats that are essential for fish reproduction which, in turn,

simple and practical analytical model for gathering information to

can cause declines in fish stocks and subsequent overexploitation. Once

assemble meaningful causal chains.

teams have ranked each of the concerns and determined the priorities

for the region, the links between the concerns are highlighted in order

Conceptual model

to identify places where strategic interventions could be applied to

A causal chain is a series of statements that link the causes of a problem

yield the greatest benefits for the environment and human societies

with its effects. Recognising the great diversity of local settings and the

in the region.

resulting difficulty in developing broadly applicable policy strategies,

the GIWA CCA focuses on a particular system and then only on those

Causal chain analysis

issues that were prioritised during the scoping assessment. The

Causal Chain Analysis (CCA) traces the cause-effect pathways from the

starting point of a particular causal chain is one of the issues selected

socio-economic and environmental impacts back to their root causes.

during the Scaling and Scoping stages and its related environmental

The GIWA CCA aims to identify the most important causes of each

and socio-economic impacts. The next element in the GIWA chain is

concern prioritised during the scoping assessment in order to direct

the immediate cause; defined as the physical, biological or chemical

policy measures at the most appropriate target in order to prevent

variable that produces the GIWA issue. For example, for the issue of

further degradation of the regional aquatic environment.

eutrophication the immediate causes may be, inter alia:

Enhanced nutrient inputs;

Root causes are not always easy to identify because they are often

Increased recycling/mobilisation;

spatial y or temporal y separated from the actual problems they

Trapping of nutrients (e.g. in river impoundments);

cause. The GIWA CCA was developed to help identify and understand

Run-off and stormwaters

the root causes of environmental and socio-economic problems

in international waters and is conducted by identifying the human

Once the relevant immediate cause(s) for the particular system has

activities that cause the problem and then the factors that determine

(have) been identified, the sectors of human activity that contribute

the ways in which these activities are undertaken. However, because

most significantly to the immediate cause have to be determined.

there is no universal theory describing how root causes interact to

Assuming that the most important immediate cause in our example

create natural resource management problems and due to the great

had been increased nutrient concentrations, then it is logical that the

variation of local circumstances under which the methodology will

most likely sources of those nutrients would be the agricultural, urban

be applied, the GIWA CCA is not a rigidly structured assessment but

or industrial sectors. After identifying the sectors that are primarily

1 This does not mean that the methodology ignores statistical or quantitative studies; as has already been pointed out, the available evidence that justifies the assumption of causal links should

be provided in the assessment.

x

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

THE GIWA METHODOLOGY

xi

responsible for the immediate causes, the root causes acting on those

The policy options recommended by the GIWA are only contributions

sectors must be determined. For example, if agriculture was found to

to the larger policy process and, as such, the GIWA methodology

be primarily responsible for the increased nutrient concentrations, the

developed to test the performance of various options under the

root causes could potential y be:

different circumstances has been kept simple and broadly applicable.

Economic (e.g. subsidies to fertilisers and agricultural products);

Legal (e.g. inadequate regulation);

Global International Waters Assessment

Failures in governance (e.g. poor enforcement); or

Technology or knowledge related (e.g. lack of affordable substitutes

for fertilisers or lack of knowledge as to their application).

Once the most relevant root causes have been identified, an

explanation, which includes available data and information, of how

they are responsible for the primary environmental and socio-economic

problems in the region should be provided.

Policy option analysis

Despite considerable effort of many Governments and other

organisations to address transboundary water problems, the evidence

indicates that there is stil much to be done in this endeavour. An

important characteristic of GIWA's Policy Option Analysis (POA) is that

its recommendations are firmly based on a better understanding of

the root causes of the problems. Freshwater scarcity, water pol ution,

overexploitation of living resources and habitat destruction are very

complex phenomena. Policy options that are grounded on a better

understanding of these phenomena wil contribute to create more

effective societal responses to the extremely complex water related

transboundary problems. The core of POA in the assessment consists

of two tasks:

Construct policy options

Policy options are simply different courses of action, which are not

always mutual y exclusive, to solve or mitigate environmental and

socio-economic problems in the region. Although a multitude of

different policy options could be constructed to address each root

cause identified in the CCA, only those few policy options that have

the greatest likelihood of success were analysed in the GIWA.

Select and apply the criteria on which the policy options will be

evaluated

Although there are many criteria that could be used to evaluate any

policy option, GIWA focuses on:

Effectiveness (certainty of result)

Efficiency (maximisation of net benefits)

Equity (fairness of distributional impacts)

Practical criteria (political acceptability, implementation feasibility).

x

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

THE GIWA METHODOLOGY

xi

Table 5a: Scoring criteria for environmental impacts of Freshwater shortage

Issue

Score 0 = no known impact

Score 1 = slight impact

Score 2 = moderate impact

Score 3 = severe impact

Issue 1: Modification

No evidence of modification of stream

There is a measurably changing trend in

Significant downward or upward trend

Annual discharge of a river altered by more

of stream flow

flow.

annual river discharge at gauging stations

(more than 20% of the long term mean) in

than 50% of long term mean; or

"An increase or decrease

in a major river or tributary (basin >

annual discharges in a major river or tributary Loss of >50% of riparian or deltaic

in the discharge of

40 000 km2); or

draining a basin of >250 000 km2; or

wetlands over a period of not less than

streams and rivers

There is a measurable decrease in the area

Loss of >20% of flood plain or deltaic

40 years (through causes other than

as a result of human

of wetlands (other than as a consequence

wetlands through causes other than

conversion or artificial embankment); or

interventions on a local/

of conversion or embankment

conversion or artificial embankments; or

Significant increased siltation or erosion

regional scale (see Issue

construction); or

Significant loss of riparian vegetation (e.g.

due to changing in flow regime (other than

19 for flow alterations

There is a measurable change in the

trees, flood plain vegetation); or

normal fluctuations in flood plain rivers);

resulting from global

interannual mean salinity of estuaries or

Significant saline intrusion into previously

or

change) over the last 3-4

coastal lagoons and/or change in the mean

freshwater rivers or lagoons.

Loss of one or more anadromous or

decades."

position of estuarine salt wedge or mixing

catadromous fish species for reasons

zone; or

other than physical barriers to migration,

Change in the occurrence of exceptional

pol ution or overfishing.

discharges (e.g. due to upstream

damming.

Issue 2: Pollution of

No evidence of pol ution of surface and

Any monitored water in the region does

Water supplies does not meet WHO or

River draining more than 10% of the basin

existing supplies

ground waters.

not meet WHO or national drinking water

national drinking water standards in more

have suffered polysaprobic conditions, no

"Pol ution of surface

criteria, other than for natural reasons; or

than 30% of the region; or

longer support fish, or have suffered severe

and ground fresh waters

There have been reports of one or more

There are one or more reports of fish kil s

oxygen depletion

supplies as a result of

fish kil s in the system due to pol ution

due to pol ution in any river draining a

Severe pol ution of other sources of

point or diffuse sources"

within the past five years.

basin of >250 000 km2 .

freshwater (e.g. groundwater)

Issue 3: Changes in

No evidence that abstraction of water from Several wel s have been deepened because Clear evidence of declining base flow in

Aquifers are suffering salinisation over

the water table

aquifers exceeds natural replenishment.

of excessive aquifer draw-down; or

rivers in semi-arid areas; or

regional scale; or

"Changes in aquifers

Several springs have dried up; or

Loss of plant species in the past decade,

Perennial springs have dried up over

as a direct or indirect

Several wel s show some salinisation.

that depend on the presence of ground

regional y significant areas; or

consequence of human

water; or

Some aquifers have become exhausted

activity"

Wel s have been deepened over areas of

hundreds of km2;or

Salinisation over significant areas of the

region.

Table 5b: Scoring criteria for environmental impacts of Pollution

Issue

Score 0 = no known impact

Score 1 = slight impact

Score 2 = moderate impact

Score 3 = severe impact

Issue 4:

Normal incidence of bacterial related

There is minor increase in incidence of

Public health authorities aware of marked

There are large closure areas or very

Microbiological

gastroenteric disorders in fisheries product

bacterial related gastroenteric disorders

increase in the incidence of bacterial

restrictive advisories affecting the

pollution

consumers and no fisheries closures or

in fisheries product consumers but no

related gastroenteric disorders in fisheries

marketability of fisheries products; or

"The adverse effects of

advisories.

fisheries closures or advisories.

product consumers; or

There exists widespread public or tourist

microbial constituents of

There are limited area closures or

awareness of hazards resulting in

human sewage released

advisories reducing the exploitation or

major reductions in the exploitation or

to water bodies."

marketability of fisheries products.

marketability of fisheries products.

Issue 5:

No visible effects on the abundance and

Increased abundance of epiphytic algae; or

Increased filamentous algal production

High frequency (>1 event per year), or

Eutrophication

distributions of natural living resource

A statistical y significant trend in

resulting in algal mats; or

intensity, or large areas of periodic hypoxic

"Artificial y enhanced

distributions in the area; and

decreased water transparency associated

Medium frequency (up to once per year)

conditions, or high frequencies of fish and

primary productivity in

No increased frequency of hypoxia1 or

with algal production as compared with

of large-scale hypoxia and/or fish and

zoobenthos mortality events or harmful

receiving water basins

fish mortality events or harmful algal

long-term (>20 year) data sets; or

zoobenthos mortality events and/or

algal blooms; or

related to the increased

blooms associated with enhanced primary Measurable shal owing of the depth range

harmful algal blooms.

Significant changes in the littoral

availability or supply

production; and

of macrophytes.

community; or

of nutrients, including

No evidence of periodical y reduced

Presence of hydrogen sulphide in

cultural eutrophication

dissolved oxygen or fish and zoobenthos

historical y well oxygenated areas.

in lakes."

mortality; and

No evident abnormality in the frequency of

algal blooms.

xii

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

THE GIWA METHODOLOGY

xiii

Issue 6: Chemical

No known or historical levels of chemical

Some chemical contaminants are

Some chemical contaminants are above

Chemical contaminants are above

pollution

contaminants except background levels of

detectable but below threshold limits

threshold limits defined for the country or

threshold limits defined for the country or

"The adverse effects of

natural y occurring substances; and

defined for the country or region; or

region; or

region; and

chemical contaminants

No fisheries closures or advisories due to

Restricted area advisories regarding

Large area advisories by public health

Public health and public awareness of

released to standing or

chemical pol ution; and

chemical contamination of fisheries

authorities concerning fisheries product

fisheries contamination problems with

marine water bodies

No incidence of fisheries product tainting;

products.

contamination but without associated

associated reductions in the marketability

as a result of human

and

catch restrictions or closures; or

of such products either through the

activities. Chemical

No unusual fish mortality events.

If there is no available data use the fol owing High mortalities of aquatic species near

imposition of limited advisories or by area

contaminants are

criteria:

outfal s.

closures of fisheries; or

here defined as

If there is no available data use the fol owing Some use of pesticides in small areas; or

Large-scale mortalities of aquatic species.

compounds that are

criteria:

Presence of small sources of dioxins or

If there is no available data use the fol owing

toxic or persistent or

No use of pesticides; and

furans (e.g., small incineration plants or

criteria:

If there is no available data use the fol owing

bioaccumulating."

No sources of dioxins and furans; and

bleached kraft/pulp mil s using chlorine);

Large-scale use of pesticides in agriculture

criteria:

No regional use of PCBs; and

or

and forestry; or

Indications of health effects resulting

No bleached kraft pulp mil s using chlorine Some previous and existing use of PCBs

Presence of major sources of dioxins or

from use of pesticides; or

bleaching; and

and limited amounts of PCB-containing

furans such as large municipal or industrial Known emissions of dioxins or furans from

No use or sources of other contaminants.

wastes but not in amounts invoking local

incinerators or large bleached kraft pulp

incinerators or chlorine bleaching of pulp;

concerns; or

mil s; or

or

Presence of other contaminants.

Considerable quantities of waste PCBs in

Known contamination of the environment

the area with inadequate regulation or has

or foodstuffs by PCBs; or

invoked some public concerns; or

Known contamination of the environment

Presence of considerable quantities of

or foodstuffs by other contaminants.

other contaminants.

Issue 7: Suspended

No visible reduction in water transparency; Evidently increased or reduced turbidity

Markedly increased or reduced turbidity

Major changes in turbidity over wide or

solids

and

in streams and/or receiving riverine and

in small areas of streams and/or receiving

ecological y significant areas resulting

"The adverse effects of

No evidence of turbidity plumes or

marine environments but without major

riverine and marine environments; or

in markedly changed biodiversity or

modified rates of release

increased siltation; and

changes in associated sedimentation or

Extensive evidence of changes in

mortality in benthic species due to

of suspended particulate No evidence of progressive riverbank,

erosion rates, mortality or diversity of flora

sedimentation or erosion rates; or

excessive sedimentation with or without

matter to water bodies

beach, other coastal or deltaic erosion.

and fauna; or

Changes in benthic or pelagic biodiversity

concomitant changes in the nature of

resulting from human

Some evidence of changes in benthic or

in areas due to sediment blanketing or

deposited sediments (i.e., grain-size

activities"

pelagic biodiversity in some areas due

increased turbidity.

composition/redox); or

to sediment blanketing or increased

Major change in pelagic biodiversity or

turbidity.

mortality due to excessive turbidity.

Issue 8: Solid wastes

No noticeable interference with trawling

Some evidence of marine-derived litter on

Widespread litter on beaches giving rise to

Incidence of litter on beaches sufficient

"Adverse effects

activities; and

beaches; or

public concerns regarding the recreational

to deter the public from recreational

associated with the

No noticeable interference with the

Occasional recovery of solid wastes

use of beaches; or

activities; or

introduction of solid

recreational use of beaches due to litter;

through trawling activities; but

High frequencies of benthic litter recovery

Trawling activities untenable because of

waste materials into

and

Without noticeable interference with

and interference with trawling activities;

benthic litter and gear entanglement; or

water bodies or their

No reported entanglement of aquatic

trawling and recreational activities in

or

Widespread entanglement and/or

environs."

organisms with debris.

coastal areas.

Frequent reports of entanglement/

suffocation of aquatic species by litter.

suffocation of species by litter.

Issue 9: Thermal

No thermal discharges or evidence of

Presence of thermal discharges but

Presence of thermal discharges with large

Presence of thermal discharges with large

"The adverse effects

thermal effluent effects.

without noticeable effects beyond

mixing zones having reduced productivity

mixing zones with associated mortalities,

of the release of

the mixing zone and no significant

or altered biodiversity; or

substantial y reduced productivity or

aqueous effluents at

interference with migration of species.

Evidence of reduced migration of species

noticeable changes in biodiversity; or

temperatures exceeding

due to thermal plume.

Marked reduction in the migration of

ambient temperature

species due to thermal plumes.

in the receiving water

body."

Issue 10: Radionuclide No radionuclide discharges or nuclear

Minor releases or fal out of radionuclides

Minor releases or fal out of radionuclides

Substantial releases or fal out of

"The adverse effects of

activities in the region.

but with well regulated or wel -managed

under poorly regulated conditions that do

radionuclides resulting in excessive

the release of radioactive

conditions complying with the Basic Safety

not provide an adequate basis for public

exposures to humans or animals in relation

contaminants and

Standards.

health assurance or the protection of

to those recommended under the Basic

wastes into the aquatic

aquatic organisms but without situations

Safety Standards; or

environment from

or levels likely to warrant large scale

Some indication of situations or exposures

human activities."

intervention by a national or international

warranting intervention by a national or

authority.

international authority.

Issue 11: Spills

No evidence of present or previous spil s of

Some evidence of minor spil s of hazardous Evidence of widespread contamination

Widespread contamination by hazardous

"The adverse effects

hazardous material; or

materials in small areas with insignificant

by hazardous or aesthetical y displeasing

or aesthetical y displeasing materials

of accidental episodic

No evidence of increased aquatic or avian

smal -scale adverse effects one aquatic or

materials assumed to be from spil age

from frequent spil s resulting in major

releases of contaminants

species mortality due to spil s.

avian species.

(e.g. oil slicks) but with limited evidence of

interference with aquatic resource

and materials to the

widespread adverse effects on resources or

exploitation or coastal recreational

aquatic environment

amenities; or

amenities; or

as a result of human

Some evidence of aquatic or avian species

Significant mortality of aquatic or avian

activities."

mortality through increased presence of

species as evidenced by large numbers of

contaminated or poisoned carcasses on

contaminated carcasses on beaches.

beaches.

xii

REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS

THE GIWA METHODOLOGY

xiii

Table 5c: Scoring criteria for environmental impacts of Habitat and community modification

Issue

Score 0 = no known impact

Score 1 = slight impact

Score 2 = moderate impact

Score 3 = severe impact

Issue 12: Loss of ecosystems or

There is no evidence of loss of

There are indications of fragmentation Permanent destruction of at least one

Permanent destruction of at least one

ecotones

ecosystems or habitats.

of at least one of the habitats.

habitat is occurring such as to have

habitat is occurring such as to have

"The complete destruction of aquatic

reduced their surface area by up to 30

reduced their surface area by >30%

habitats. For the purpose of GIWA

% during the last 2-3 decades.

during the last 2-3 decades.

methodology, recent loss will be

measured as a loss of pre-defined

habitats over the last 2-3 decades."

Issue 13: Modification of

No evidence of change in species

Evidence of change in species

Evidence of change in species

Evidence of change in species

ecosystems or ecotones, including

complement due to species extinction

complement due to species extinction

complement due to species extinction

complement due to species extinction

community structure and/or species

or introduction; and

or introduction

or introduction; and

or introduction; and

composition

No changing in ecosystem function

Evidence of change in population

Evidence of change in population

"Modification of pre-defined habitats

and services.

structure or change in functional group

structure or change in functional group

in terms of extinction of native species,

composition or structure

composition or structure; and

occurrence of introduced species and

Evidence of change in ecosystem

changing in ecosystem function and

services2.

services over the last 2-3 decades."

2 Constanza, R. et al. (1997). The value of the world ecosystem services and natural capital, Nature 387:253-260.

Table 5d: Scoring criteria for environmental impacts of Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other

living resources

Issue

Score 0 = no known impact

Score 1 = slight impact

Score 2 = moderate impact

Score 3 = severe impact

Issue 14: Overexploitation