(1,1) -1- Cover 38_only.indd 2004-04-05, 16:09:52

Global International

Waters Assessment

Patagonian Shelf

GIWA Regional assessment 38

Mugetti, A., Brieva, C., Giangiobbe, S., Gallicchio, E., Pacheco, F.,

Pagani, A., Calcagno, A., González, S., Natale, O., Faure, M.,

Rafaelli, S., Magnani, C., Moyano, M.C., Seoane, R. and I. Enriquez

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment 38

Patagonian Shelf

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Report editors: David Souter, George Roman

Editorial assistance: Johanna Egerup, Malin Karlsson

Maps & GIS: Niklas Holmgren

Design & graphics: Joakim Palmqvist

Global International Waters Assessment

Patagonian Shelf, GIWA Regional assessment 38

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2004 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-9403

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and

in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without

special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this

publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the

United Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2004. Mugetti, A., Brieva, C., Giangiobbe, S., Gallicchio, E.,

Pacheco, F., Pagani, A., Calcagno, A., González, S., Natale, O.,

Faure, M., Rafaelli, S., Magnani, C., Moyano, M.C., Seoane, R. and

Enriquez, I. Patagonian Shelf, GIWA Regional assessment 38.

University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and do not necessarily reflect those of UNEP. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating

agencies concerning the legal status of any country, territory,

city or areas or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information

herein is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not

warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Printed and bound in Sweden by Sunds Tryck Öland AB.

CONTENTS

Contents

Executive summary

9

La Plata River Basin

9

South Atlantic Drainage System

11

Acknowledgements

13

Abbreviations and acronyms

14

Regional definition

18

Boundaries of the Patagonian Shelf region

18

Physical characteristics

19

Socio-economic characteristics

27

Assessment

34

La Plata River Basin

Freshwater shortage

35

Pollution

40

Habitat and community modification

47

Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources

52

Global change

55

South Atlantic Drainage System

Freshwater shortage

58

Pollution

61

Habitat and community modification

66

Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources

68

Global change

72

Priority concerns: La Plata River Basin & South Atlantic Drainage System

74

Causal chain analysis

76

Uruguay River Basin upstream of the Salto Grande Dam

System description

76

Impacts

80

Immediate causes

81

Root causes

82

CONTENTS

Buenos Aires Coastal Ecosystem Argentinean-Uruguayan Common Fishing Zone

System description

86

Causal model and links

90

Root causes

93

Conclusions

96

Policy options

98

Uruguay River Basin upstream of the Salto Grande Dam

Definition the of problem

98

Construction of policy options

99

Performance of selected policy options

100

Final considerations

103

Buenos Aires Coastal Ecosystem Argentinean-Uruguayan Common Fishing Zone

Definition of the problem

105

Construction of policy options

106

Identification of recommended policy options

108

Performance of selected policy options

109

Conclusions and recommendations

113

La Plata River Basin

113

South Atlantic Drainage System

115

Further research recommended for the Patagonian Shelf region

117

References

118

Annexes

128

Annex I List of contributing authors and organisations involved

128

Annex II Detailed scoring tables

131

Annex III Detailed assessment worksheets for causal chain analysis

139

Annex IV List of important water-related programmes and assessments in the region

152

Annex V List of conventions and specific laws

153

Annex VI Tables

160

The Global International Waters Assessment

i

The GIWA methodology

vii

Executive summary

GIWA region 38, Patagonian Shelf, comprises the La Plata River Basin, the

Assessment

South Atlantic Drainage System, and the Patagonian Shelf Large Marine

The impacts of Freshwater shortage in the La Plata River Basin were

Ecosystem. Given the significant differences in terms of biophysical and

assessed as moderate. Although freshwater supply aggregated at basin

socio-economic aspects, the assessment was carried out separately

level greatly exceeds demand, the temporal and spatial distribution of

for two systems: La Plata River Basin and the South Atlantic Drainage

flow is uneven, and the degradation of water quality by pol ution is

System.

progressively decreasing the usability of supplies. Shortages in many

locations have already been observed, and these are likely to become

more common in the future.

La Plata River Basin

The modification of water sources around major cities, the rising costs of

water treatment, and the high cost of restoring degraded water sources

The La Plata River Basin is shared by Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay

stand out as pressing socio-economic issues that could potential y

and Uruguay. Covering over 3.1 mil ion km2, it is the second largest

initiate conflicts at both sub-national and regional levels.

drainage basin in South America and the fifth largest in the world. The

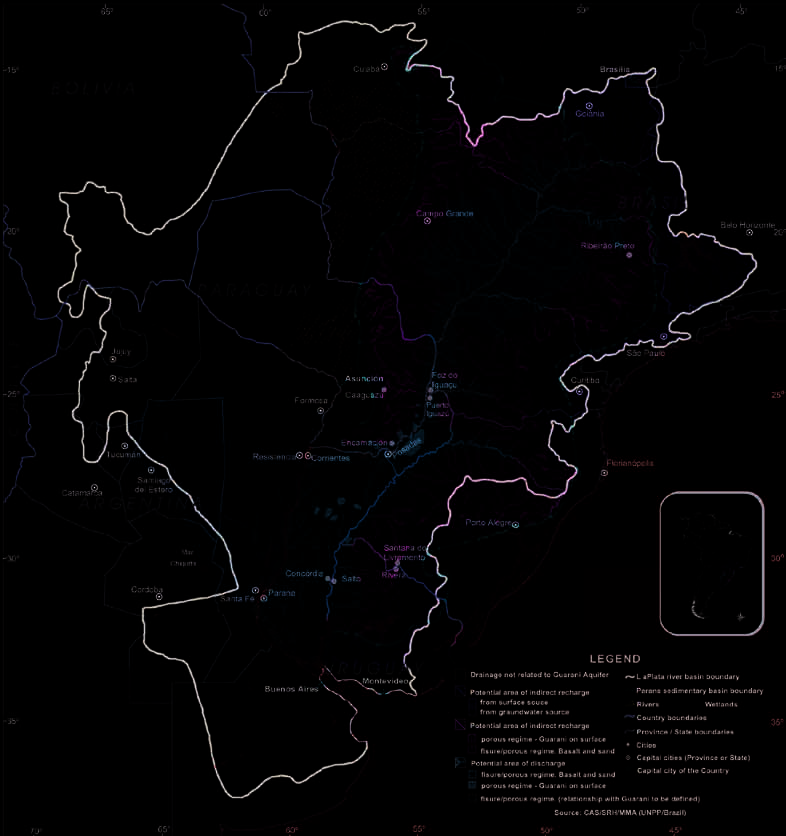

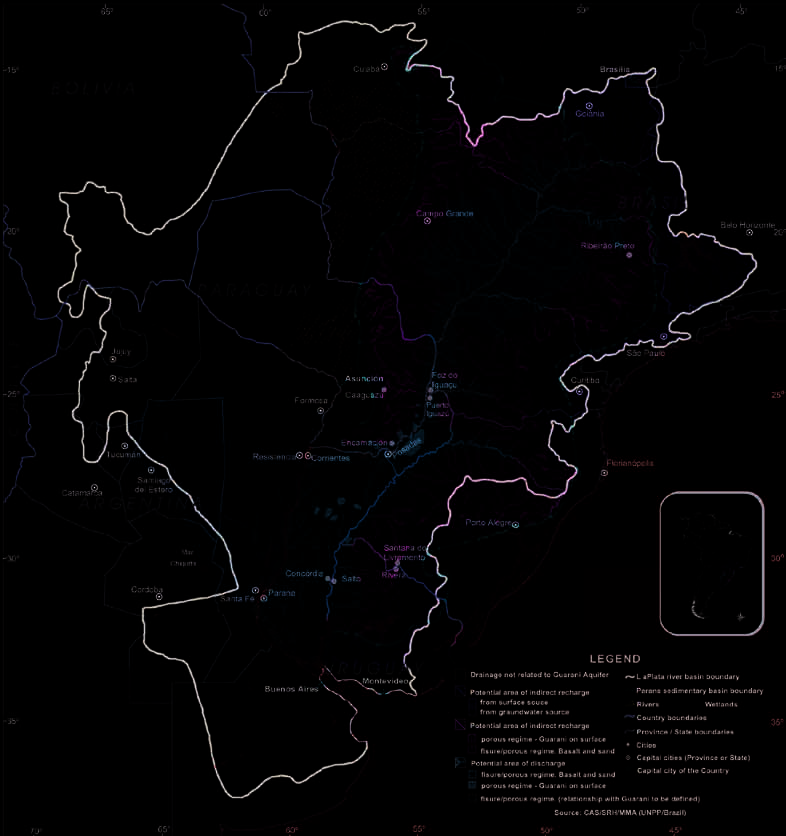

Guaraní Aquifer, shared by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, and

The impacts of Pol ution in the Basin were assessed as moderate.

containing over 40 000 km3 of freshwater, is also located in the region.

The limited treatment of industrial wastes leads to widespread

contamination by chemical pol utants. The lack of sewage treatment

The region contains many large urban and industrial centres and

leads to the contamination of supplies by pathogens, particularly in the

political y important cities, including Buenos Aires, Asuncion,

vicinity of cities. The use of agro-chemicals has introduced significant

Montevideo, Brasilia, Sao Paulo, and Curitiba.

sources of chemical pollutants, and there is evidence of eutrophication

in some areas of large reservoirs. In addition, land use changes and

The Basin is an important centre for the regional economy. Approximately

unsustainable agricultural practices have resulted in erosion that has

50% of the population of the countries sharing the La Plata Basin live

greatly increased the turbidity of water supplies. Final y, occasional

within the drainage basin while around 70% of GNP of the countries

significant oil spil s occur.

involved is produced within the same area.

Economic impacts associated with Pollution were assessed as severe,

The La Plata River Treaty provides a supra-national legal framework

particularly due to increases in water treatment costs. There is also

for the region, and the Intergovernmental Coordinating Committee

considerable evidence of health impacts due to water-borne diseases.

(CIC) of the La Plata River Basin provides an institutional framework

For example, diarrhoea and schistosomiasis are common, and during

for management. International institutional agreements and basin

the 1990s, cholera epidemics were registered in al of the countries

committees can also be found within several sub-basins.

of La Plata River Basin except Uruguay. At local levels, there has been

evidence of decreased viability of fish stocks due to pol ution. Future

improvements in pol ution control wil require major investments,

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

9

but are necessary for avoiding health problems, as wel as a range of

Based on the assessment of each major concern and the constituent

environmental and social impacts.

issues, and a consideration of environmental, socio-economic, and

health impacts, the GIWA Task team prioritised Pol ution for further

The impacts of Habitat and community modification were assessed as

analysis, and chose the Uruguay River Basin to il ustrate the Causal

moderate. The construction of reservoirs for hydropower generation

chain and Policy options analyses.

has caused modifications to several types of fluvial and riparian

ecosystems. Migratory routes of fish species have been disturbed,

Causal chain analysis and Policy option analysis

flow regulation has affected species that use downstream floodplains

for Pollution: Uruguay River Basin upstream

for spawning, and there have been records of fish mortality due gas

from the Salto Grande Reservoir

supersaturation caused by dam operations. In addition, alien bivalve

The primary immediate causes of pollution in the Uruguay River Basin

species accidental y introduced from Asia (Limnoperna fortunei and

were identified as: inadequate treatment of urban and industrial

Corbicula fluminea) have spread throughout a large part of La Plata

wastewater, application of agro-chemicals (fertilisers and biocides),

River Basin and have displaced native benthic species. An increasing

inefficient irrigation practices, and soil erosion.

abundance of carp in the inner La Plata, Paraná and Uruguay rivers has

also been evident. Urbanisation has also resulted in the loss of certain

Identified root causes for pollution include:

aquatic ecosystems types.

Lack of a framework for Integrated Water Resources Management,

and lack of coordination between different levels of government;

Socio-economic impacts caused by these changes include the loss of

Lack of stakeholder participation in decision-making;

educational and scientific values, and increased costs associated with

Inadequate valuation of ecosystem goods and services;

the control of invasive species and the restoration of habitats. Future

Persistence of unsustainable agricultural practices;

impacts due to habitat modification are likely to either continue to

Inadequate budgets of institutions in charge of management, which

worsen, or to improve slightly.

contributes to the lack of enforcement of existing agreements and

policies;

The impacts of Unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living

Poor spread of scientific and technological knowledge and

resources were assessed as moderate. The sustainability of major

training;

commercial and recreational inland fisheries in the La Plata River

Market incentives for short term economic gain;

Basin are at risk due to inadequate management practices and

Poverty.

overexploitation. When combined with habitat modification, pol ution,

and impending climate change, overexploitation is threatening the

After analysing several policy options, the fol owing policy instruments

long-term viability of fish stocks.

were highlighted as recommended options:

Improved wastewater treatment by strengthening and

Although the fishing sector is smal , socio-economic impacts have been

coordinating financial mechanisms between private and public

assessed as considerable due to subsistence concerns associated with

sectors (including international sources);

non-professional fishermen. A moderate increase in the impacts due to

Promote sustainable agricultural practices by enforcing regulations

fishing are expected in the future.

concerning agrochemicals (`pol uter pays'), facilitating the

introduction of practices that reduce soil erosion, and making

The impacts of Global change were assessed as moderate. The La Plata

irrigation more efficient (`user pays');

River Basin has been extensively influenced by climatic variability and is

Carry out systematic campaigns of environmental awareness and

very sensitive to El Niño events. In spite of present uncertainties, global

education that target specific stakeholders;

change seems to have had a significant effect on the hydrological

Use subsidies to promote the treatment and/or reuse of wastes

cycle, and cities located in the vicinity of rivers are now at greater risk

originating from livestock production;

of flooding disasters, especial y in Argentina. In the future, it is assumed

Create basin management mechanisms with transboundary,

that global change will cause the global hydrological cycle to become

integrated approaches. These would include and/or extend the

more volatile and unpredictable, which wil increase the risk of flooding

scope of existing institutions.

and attendant socio-economic consequences due to impacts upon

infrastructure, agricultural production, and the economy.

10

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

South Atlantic Drainage System Based on the assessment of the major concerns and their issues, the

fol owing linked concerns were prioritised within the transboundary

The South Atlantic Drainage System comprises basins located between

regions of the Argentinean-Uruguayan Common Fishing Zone and the

the Andean ranges and the Atlantic Ocean, which drain large arid areas

Buenos Aires Coastal Ecosystem:

of Argentina and some small parts of southern Chile. This sub-system

Habitat and community modification, which is tightly linked to

also contains one of the world's largest continental shelves, which

unsustainable exploitation of fish and other living resources, and

is over 769 400 km2, and extends up to 850 km from the coast at its

also linked to pollution.

southernmost point.

Causal chain analysis and Policy option analysis

This system is characterised by very low population densities, and the

for the Argentinean-Uruguayan Common Fishing

primary economic activities include farming (e.g. fruit, sheep), mining

Zone and the Buenos Aires Coastal Ecosystem

(oil and coal), and fishing.

The Argentinean-Uruguayan Common Fishing Zone and the Buenos

Aires Coastal Ecosystem were selected as a case study for the Causal

Assessment

chain and Policy options analyses. The most significant immediate

The impacts of Freshwater shortage were assessed as moderate.

causes of habitat modification are related to the fisheries sector,

Localised overexploitation of groundwater and pol ution of water

and include: overexploitation of target species, by-catch, and the

supplies have had major impacts on freshwater supplies. In addition,

modification of the sea floor by fishing gear. Other significant causes

the construction and operation of dams has modified riparian habitats

of habitat modification include urbanisation and shipping activities.

and changed seasonal flow patterns.

Habitats are also being altered by pollution originating from urban and

industrial wastewater discharges and agricultural non-point sources.

The impacts of Pollution were assessed as slight. Oil spil s, suspended

solids, and microbial pol ution are responsible for most of the

Besides market forces, the primary root cause for habitat modification

environmental impacts. Wastewater discharges are the main sources

is a general lack of surveil ance and regulation. This applies primarily

of microbiological pol ution. The extensive use of pesticides and

to fishing activities, but also to urbanisation, tourism development,

fertilisers has impacted some lakes, and eutrophication has been

and agriculture. Ineffective governance leads to inadequacies in the

evident in areas with restricted water circulation. In addition, oil spil s

budgets and personnel of agencies charged with management, hinders

and toxic waste spil s have had negative impacts on both ecosystems

the efficient application of legal instruments, and contributes to a lack

and water supplies.

of research and knowledge development. There is also a lack of consent

between Argentina and Uruguay in many aspects related to joint

The impacts of Habitat and community modification were assessed

administration of shared resources and joint research and assessment

as moderate. Marine ecosystems have been extensively modified due

of ecosystems. In addition, technology to increase selectivity of fishing

to fishing, dredging and tourism development. In addition, reservoir

gears is missing, and fishers show significant socio-cultural resistance

development has altered many fluvial and riparian ecosystems,

to the use or development of new types of fishing gear.

particularly in the Limay River.

Policy options to address the identified root causes require

The impacts of Unsustainable exploitation of fish were assessed as

management policies based on a set of multiple tools that should be

moderate. Hake has been exploited beyond safe biological limits,

applied simultaneously. Recommended actions include:

resulting in the col apse of fish stocks. Overexploitation, by-catches

Demarcate a coastal area and restrict fishing operations in this area

and discards of organisms without commercial value, and habitat

to small boats only (under 25-30 m);

destruction by trawling methods have generated threats to ecosystem

Include a National Programme of Preservation of the Marine

integrity and marine biodiversity.

Environment within Argentina's Science and Technology System

(SCYT);

The impacts of Global change on the South Atlantic Drainage System

Link fisheries development to national programmes for the

were assigned a score of 0 or no impact. However, impacts of global

preservation of the marine environment;

change are expected to increase in the future.

Reorient research policies to reconcile research and development

issues with state policies;

10

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

Optimise national, provincial, and state budget al ocations to

fisheries management agencies;

Develop a mechanism to finance long-term research aimed at

achieving the sustainable management of ecosystems;

Strengthen efforts to systematical y compile and analyse fisheries

data;

Coordinate research data from several projects at both national and

international levels;

Regulate fishing efforts "in paral el" (Argentina-Uruguay), al owing

each country to develop its own fishery exploitation models and

then reconcile both practices;

Jointly evaluate the state of resources and obtain more reliable

scientific data. This requires continuous bi-national research

campaigns;

Promote the exchange of data and knowledge among regional

organisation through research units and workshops (Argentina,

Uruguay, Brazil) to identify shared resources and assess genetic

diversity;

Optimise communication systems among scientists, administrators

and managers;

Improve the capacity of land-based and on-board fisheries

inspectors to undertake control and monitoring activities;

Involve fishermen in developing selective practices and devices;

Disseminate information throughout communities in order to

foster public awareness about goods and services related to marine

ecosystems;

Launch educational campaigns among the general population

to discourage consumption of products based on endangered

species, or species whose exploitation is likely to undermine the

integrity of the ecosystem or disrupt ecosystem function;

Carry out technical studies to develop selective fishing gear that

minimises by-catch and safeguards biodiversity and habitats;

Expand research on species exposed to incidental exploitation.

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

Acknowledgements

The Argentine Institute of Water Resources (IARH) has been the Focal

Point for the regional GIWA assessment of the Patagonian Shelf.

The Argentine Institute of Water Resources (IARH) is a non-

governmental organisation created in 1984 by professionals interested

in water resources management. Its goal is the study, promotion and

dissemination of issues related to the knowledge, use, preservation

and management of water resources. In doing so, IARH promotes

experience and professionals and institutions exchange, from both

national and foreign locations. Among other activities, IARH gives

specialised courses, organises technical meetings, workshops and

seminaries, edits a newsletter, elaborates and disseminates reports,

and fosters debate about relevant rational use, preservation and

integrated water resources management. Since 1994, IARH has actively

participated in the RIGA (Environmental and Management Research

Network of La Plata Basin) implementation process.

The conduct of this project has been made possible by the col aboration

of a large number of professionals and specialist who have contributed

to it through the compilation of information and participation in the

GIWA workshops. Therefore the Coordination of the Patagonian Shelf

region would like to express thanks to the fol owing persons who have

contributed to the success of the project: Ricardo Delfino, María Josefa

Fioriti, Marcelo Gaviño Novil o, Carlos Lasta, Oscar Padín, Sara Sverlij,

Carlos Tucci and Víctor Pochat.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

13

Abbreviations and acronyms

AIC

Autoridad Interjurisdiccional de Cuenca de los ríos Limay-

CLAEH

Centro Latinoamericano de Economia Humana

Neuquen y Negro/Interjurisdictional Basin Authority of the

CODEVASF Companhia de Desenvolvimento do Vale do São Francisco

Limay-Neuquen and Negro River

COFREMAR Comisíon Técnica Mixta del Frente Marítiom/Technical

AIDIS

Asociación Argentina de Ingeniería Sanitaria y Ciencias del

Commission of Maritime Front

Ambiente

COIRCO

Comisión Interjurisdiccional del Río Colorado Argentina/Inter

ANA

Agencia Nacional del Agua, Brazil/National Water Agency,

Jurisdictional Committee of Colorado river Argentina

Brazil

COMIBOL Corporación Minera de Bolivia / Mining Corporation of

ANEEL

Agencia Nacional de Energia Electrica, Brasil/National

Bolivia

Agency of Electric Energy, Brazil

COMIP

Comisión Mixta Argentino-Paraguaya del Río Paraná/

BID

Banco Interamericano de Desarrol o/Inter American

Paraná River Argentine-Paraguayan Commission

Development Bank

COMSUR

Bolivia's Compañia Minera del Sur

BTEX

Volatile lineal and aromatic hydrocarbons

CONAMA Comision Nacional de Meio Ambiente, Brasil/National

CARP

Comisión Mixta Administradora del Río de la Plata/

Committee of Environment, Brazil

Administration Commission of the La Plata River; Argentina

CONICET

Proyecto Peces Patagónicos en el Cenpat

and Uruguay

COPEL

Companhia Paranense de Energia

CARU

Comisión Administradora del Río Uruguay/Administrative

CPUE

Catch per Unit of Effort

Commission for the Uruguay River

CRC

River Cuareim Commission

CCREM

Canadian Council of Resource and Environment Ministers

CYTED

Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el

CEHPAR

Centro de Hidráulica e Hidrologia Professor Parigot de Souza"

Desarrol o

CELA

Centro de Economía, Legislación y Administración del Agua

DFS

Dirección de Fauna Silvestre

CENPAT

Centro Nacional Patagónico

DINAMA

Dirección Nacional de Medio Ambiente

CEPIS

Centro Panamericano de Ingeniería Sanitaria y Ciencias del

DINARA

Dirección Nacional de Recursos Acuáticos/Uruguayan

Ambiente/Pan-American Center of Sanitary Engineering

Director of Aquatic Resources

and Environmental Sciences

DNH

Dirección Nacional de Hidrografía, Uruguay/National

CESP

Companhia Energética de São Paulo

Hydrographic Steering, Uruguay

CETA

Centro de Estudios Transdisciplinarios del Agua

DNPCyDH Dirección Nacional de Políticas Coordinación y Desarrol o

CETESB

Companhia de Tecnología de Saneamento Ambiental, São

Hídrico

Paulo, Brasil

DNPH

Dirección Nacional de Programas Habitacionales

CFP

Federal Fishing Council

DRIyA

Dirección Nacional de Recursos Ictícolas y Acuícolas,

CIC

Intergovernmental Co-ordinating Committee for La Plata

Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrol o Sustentable de la

Basin

Nación, Argentina / National Department of Ichthyic and

CITES

Convention for the International Trade on Endangered

Aquatic Resources, National Secretariat of Environment and

Species of Wild Flora and Fauna

Sustainable Development, Argentina

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

15

ENAPRENA Estrategia Nacional parala Proteccióny el Manejo de los

INTA

Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria

Recursos Naturales del Paraguay

IPCC

Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change

ENOHSA

Ente Nacional de Obras Hídricas de Saneamiento, Argentina

IPH

Instituto de Pesquisas Hidráulicas

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

IRGA

Instituto Riograndense de Arroz

FECIC

Fundación para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura,

LME

Large Marine Ecosystems

Argentina/Education, Science and Culture Foundation,

MAC

Maximum Al owable Catches

Argentina

MERCOSUR Mercado Común del Sur/Southern Common Market

FEP

Fisheries Economic System

MTOP

Ministerio de Transporte y Obras Públicas

FICH

Facultad de Ingenieria y Ciencias Hidricas

NGO

Non Governmental Organisations

FI-UNLP

Facultad de Ingeniería - Universidad Nacional de La Plata

NTU

Nephelometric Turbidity Unit

FPN

Fundación Patagonia Natural

OEA

Organización de los Estados Americanos

FREPLATA Protección Ambiental del Río de la Plata y su Frente

OMS

Organización Mundial de la Salud/World Health Organization

Marítimo/Environmental Protection Project of the Río de

OPS

Organización Panamericana de la Salud/Panamerican

la Plata and Its Sea Coast

Health Organization

FUCEMA

Fundación para la Conservación de las Especies y el Medio

PAH

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Ambiente

PLAMACH-BOL

FUEM

Fundação Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Nupelia and

Plan Nacional de Cuencas Hidrográficas de Bolivia/National

Itaipú Binacional

Plan of Hydrologic Basins, Bolivia.

GCM

General Circulation Model

POP

Persistent Organic Pollutant

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

PROSAP

Programa de Servicios Agrícolas Provinciales/Provincial

GEF

Global Environment Facility

Agricultural Services Program

GFDL

US national Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

ROU

República Oriental del Uruguay

Geophysical Fluids Dynamic

SABESP

Companhia de Saneamiento Básico do Estado de São Paulo,

GISS

US NASA Goddard Institute for Space Sciences

Brasil/Basic Sanitation Company of São Paulo State, Brazil

GIWA

Global International Waters Assessment

SAGPyA

Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganaderìa, Pesca y Alimentación/

GNP

Gross National Product

Argentinean Secretary of Agriculture, Cattle Raising, Fishing

GWP

Global Water Partnership

and Food

HDI

Human Development Index

SAyDS

Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrol o Sustentable

IARH

Instituto Argentino de Recursos Hídricos/Argentinean

SCYT

Argentina's science and technology system

Institute of Water Resources

SECyT

Argentinean National System of Science and Technique

IBGE

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografía e Estatística/Brazilian

SEMA

Secretaria de Estado do Meio Ambiente do Paraná

Institute of Geography and Statistical

SENASA

Servicio Nacional de Sanidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria,

ICA

Instituto Correntino del Agua

Argentina

IDB

International Development Bank

SSRH

Subsecretaría de Recursos Hídricos de la Nación, Ministerio

IHH

El Instituto de Hidráulica e Hidrología

de Economía, Argentina/National Undersecretariat of

ILEC

International Lake Environment Committee Foundation

Water Resources, Ministry of Finance, Argentina

INA

Instituto Nacional del Agua, Argentina /National Institute

THL

Trialomethanes

of Water, Argentina

THM

Tri-Halo-Methane

INDEC

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, Argentina/

UBA

Universidad de Buenos Aires

National Institute of Statistical and Census, Argentina

UFRGS

Universidade Federal Rio Grande do Sul

INE-Bolivia Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Bolivia / National Institute

UI C

Uniform International Industrial Classification

of Statistical, Bolivia

UKMO

United Kingdom Meteorological Office

INE-Uruguay Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Uruguay/National Institute

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

of Statistical, Uruguay

UNL

Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Santa Fe, Argentina

INIDEP

Instituto Nacional de Investgacíon y Desarrol o Pesquero/

WCU

World Conservation Union

National Institute of Fisheries Research and Development

ZCP

Common Fising Zone (Uruguay and Argentina)

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

15

List of figures

Figure 1

Boundaries of the Patagonian Shelf region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Figure 2

Boundaries between La Plata River Basin, South Atlantic Drainage System, and GIWA region 39 Brazil Current.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Figure 3

The drainage basins of the tributaries comprising La Plata River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Figure 4

Climate zones.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Figure 5

Ecoregions.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Figure 6

Land cover. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Figure 7

Main reservoirs in La Plata River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Figure 8

Guaraní Aquifer.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Figure 9

South Atlantic Drainage System and main reservoirs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Figure 10 Ramsar sites and protected areas. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Figure 11 Political division of the Patagonian Shelf region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Figure 12 Variation in annual water level at Ladário (Upper Paraguay) and rainfall (3 year moving average) at Cuiabá (Paraguay River).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Figure 13 Daily minimum mean and annual mean flow of Paraná River at Tunel (Paraná-Santa Fe, Argentina). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Figure 14 Water quality in the Brazilian area of La Plata River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Figure 15 Aerial view of São Paulo Metropolitan area (Brazil). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Figure 16 Location of major cities in Metropolitan area of Buenos Aires. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Figure 17 Water quality for leisure use in Paranoa Lake, Brasilia (Brazil). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

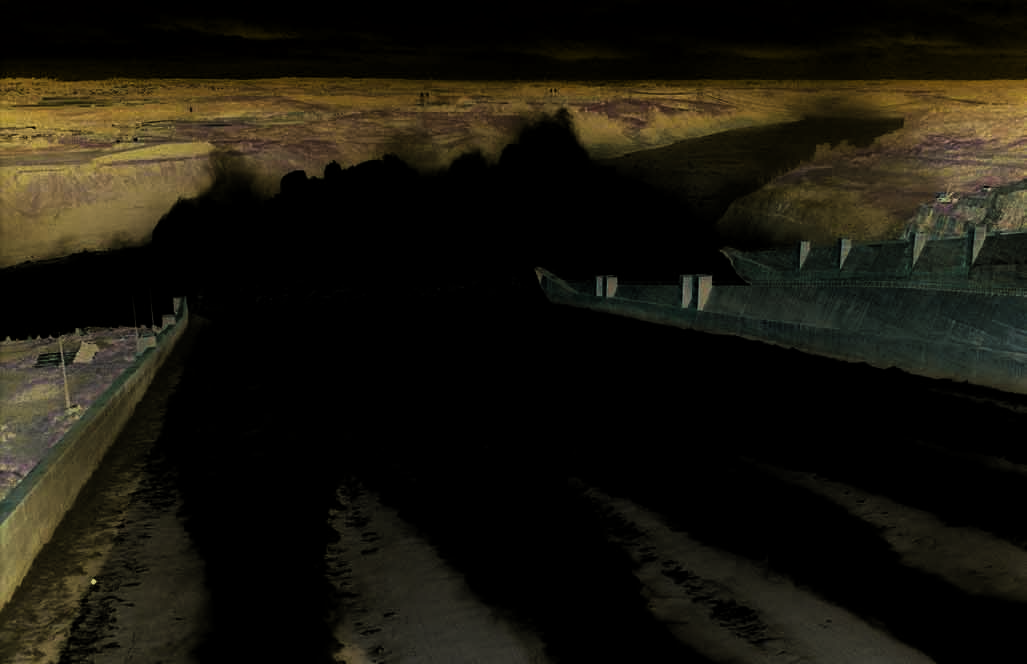

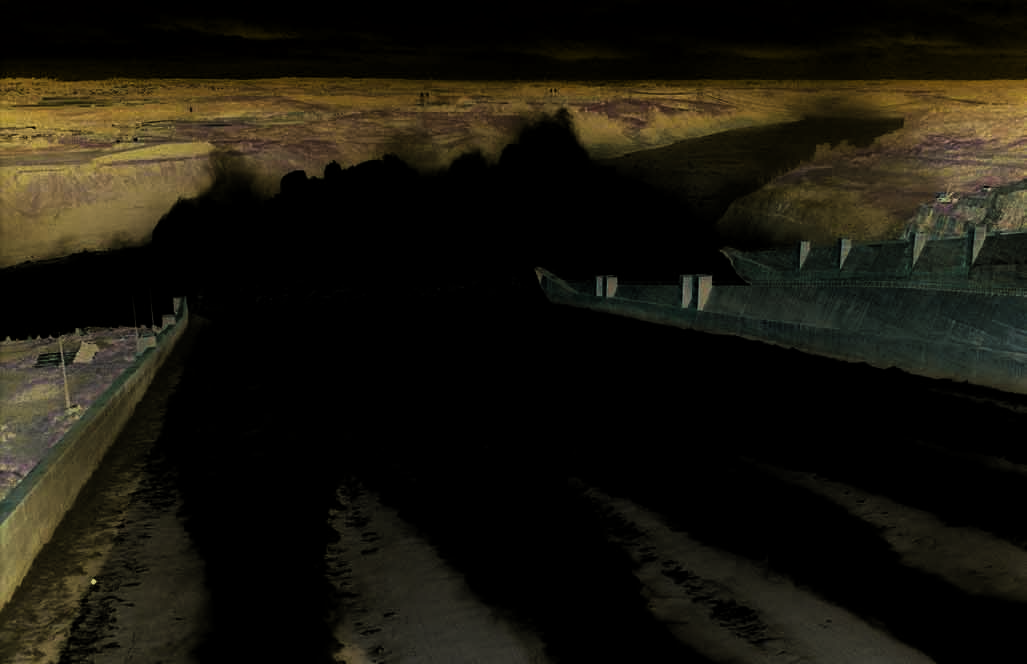

Figure 18 Itaipú dam, Paraná River.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Figure 19 Relative frequency of species in Itaipú River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Figure 20 Percentage of species transferred in Yacyretá Reservoir (Argentina-Paraguay). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Figure 21 Riachuelo River in Buenos Aires (Argentina). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Figure 22 Annual discharge at Puente Camino Buen Pasto gauging site. Senguerr River near Colhué Huapi Lake.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Figure 23 Discharge at Paso Cordoba gauge (province of Río Negro) before operation of Cerros Colorados System (1978). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Figure 24 Discharges at Paso Cordoba gauge (province of Río Negro) after operation of Cerros Colorados System (1978). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

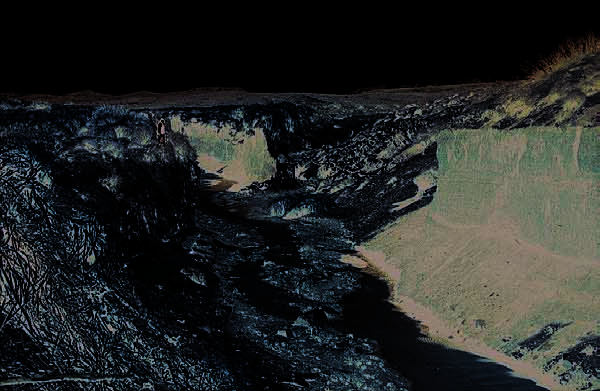

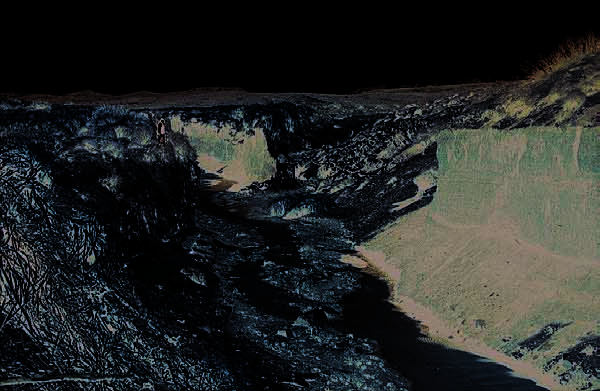

Figure 25 Main gully downstream the Aguada del Sapo mallín. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Figure 26 Fish landings in 1950-2001. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Figure 27 Argentine fish export between 1987 and 1999.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

Figure 28 Links between the GIWA concerns.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

Figure 29 Uruguay River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Figure 30 Sowed area by jurisdiction in the Uruguay River Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Figure 31 Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for Pollution in the Uruguay River Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

Figure 32 Buenos Aires Coastal Ecosystem and Argentinean-Uruguayan Fishing Zone and their relative location in South Atlantic Drainage System.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

Figure 33 Average landings of main species in the Buenos Aires Coastal Ecosystem,1992-1999.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Figure 34 Average landings of main species unloaded in Uruguayan ports, 1992-1999. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Figure 35 Hake landings in the Common Fishing Zone. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Figure 36 Causal chain diagram illustrating the causal links for Habitat and community modification in the Buenos Aires Coastal Ecosystem Argentinean-Uruguayan Common

Fishing Zone. 91

Figure 37 Effort, total landings and landing of condrichthyes from the coastal fleet of Buenos Aires and Uruguay. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Figure 38 Catch of Whitemouth croaker (Micropogonias furnieri) from the Argentinean and Uruguayan fleets at the Common Fishing Zone. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

17

List of tables

Table 1

Selected sub-systems for region 38 Patagonian Shelf.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Table 2

Main rivers of La Plata River Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Table 3

Main chemical characteristics of La Plata Basin rivers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Table 4

Main rivers of South Atlantic Drainage System. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Table 5

Gross domestic product by country. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Table 6

Structure of economy by country.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Table 7

Distribution of income in urban households, by quintiles. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Table 8

Poor households in urban and rural areas by country.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Table 9

Total population, area, density, and population growth per country. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Table 10

Population with access to drinking water and sanitation.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Table 11

Annual extraction of water by economic sector. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Table 12

Harvested area and percentage covered by main crops by country. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Table 13

Area under irrigation in the La Plata River Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Table 14

Total population, area, density and population growth in the Argentinean provinces of the South Atlantic Drainage System. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Table 15

Main cities of South Atlantic Drainage System. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Table 16

Evolution of areas under irrigation in Argentinean provinces of South Atlantic Drainage System. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Table 17

Argentinean PROSAP projects. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Table 18

High Seas fishing in South Atlantic Drainage System by port. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Table 19

Coastal fishing in South Atlantic Drainage System by port. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Table 20

Evolution of the coastal fleet crew employment in the South Atlantic Drainage System. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Table 21

Scoring table for La Plata River Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Table 22

Water quality in transboundary reaches of Brazilian rivers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Table 23

Deforestation evolution in São Paulo and Paraná states (Brazil) and in eastern Paraguay. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Table 24

Mean annual residence time of water in river sub-systems of La Plata River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Table 25

Major floods in northeast Argentina. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Table 26

Number of people evacuated, auto-evacuated and isolated during three major floods in northeast Argentina.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Table 27

Scoring table for South Atlantic Drainage System. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Table 28

Main reservoirs built in the South Atlantic Drainage System.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66

Table 29

Hake landings and percentage of overfishing in Argentina.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Table 30

Composition by species of the secondary fishing of prawn in Argentina. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Table 31

Precipitation variation scenarios for the different Argentinean regions.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

Table 32

Main hydrological characteristics of Uruguay River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

Table 33

Total and urban population with access to sewage system and drinking water in Uruguay River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

Table 34

Infant mortality rate in Uruguay River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Table 35

Total cultivated area and the percentages of rice and soybean in Uruguay River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Table 36

Total population and inter-census population growth of main coastal cities in selected oceanic systems.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

Table 37

Fish landing in the main ports of Buenos Aires province, Argentina 1991-2000. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

Table 38

Fish landings in the main Uruguayan ports. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

Table 39

Landing by type of fleet in Buenos Aires province ports, Argentina. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90

Table 40

Summary of root causes related to modification of the sea floor by destructive fishing practices. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

Table VI.1 Main cities of La Plata Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 160

Table VI.2 Hydropower and dams in La Plata River Basin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

Table VI.3 Hydropower and dams in the South Atlantic Drainage System. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

17

Regional definition

Brieva, C., Enriquez, I., González, S., Magnani, C., Mugetti, A. and S. Rafael i

This section describes the boundaries and the main physical and

socio-economic characteristics of the region in order to define the

Brasilia

area considered in the regional GIWA assessment and to provide

Paraguai

sufficient background information to establish the context within

Bolivia

which the assessment was conducted.

Brazil

Grande

Tiet

Pilcom

e

ay

ParanaibaParanapanema

Bermej

o

Paraguay

o

Boundaries of the Patagonian

Chile

La Plata River

Asuncion

Iguaz

Sao Paulo

ú

Curitiba

Shelf region

Sa

Basin

lad

Paraná

o

The Patagonian Shelf, GIWA region 38, is located in southern South

ai

Paraguay

America and comprises the entire La Plata River Basin, a major part of the

Argentina

Urugu

Argentinean continental territory, the Chilean basins draining Argentina

Cordoba

into the South Atlantic Ocean, and part of the Uruguay maritime shelf

Rosario

(Figure 1). The six countries entirely or partly located within the

Uruguay

region are Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay. The

South Atlantic

Buenos Aires Montevideo

boundaries between the Patagonian Shelf region and the GIWA regions

Drainage System

39 (Brazil Current), 40a (Brazilian Northeast) and 40b (Amazon) to the

C

north fol ow the limits of the La Plata drainage basin. In the west, the

olorado

Rio Negr

watershed between the Atlantic and Pacific drainage systems defines

o

the boundary with GIWA region 64 (Humboldt Current). To the east, the

oceanic border corresponds with the borders of the Patagonian Shelf

Elevation/Depth (m)

Large Marine Ecosystem.

3 000

2 000

1 000

Given the significant differences in terms of physical, environmental

500

100

and socio-economic characteristics between La Plata River Basin and

0

-200

the South Atlantic Drainage System, the Assessment was conducted

-1 000

separately for each system (Figure 1). This division also facilitated

-2 000

-3 000

data organisation, as wel as assessment development since the

La Plata River Basin already has an institutional framework set by the

0

500 Kilometres

© GIWA 2004

Figure 1

Boundaries of the Patagonian Shelf region.

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

REGIONAL DEFINITION

19

Intergovernmental Coordinating Committee (CIC) for the La Plata Basin,

Florianopolis

Argentina

and because some basin-wide studies has been performed in the last

Brazil

GIWA region 39

Uruguay

Paraná

three decades. Strongly differing cultural features and, consequently,

Brazil Current

different natural resource management characterise both systems.

Both systems were separated into sub-systems comprising international

Uruguay

GIWA region 38

reaches or sub-national inter-jurisdictional continental waters (Table 1)

La Plata River Basin

Negro

and the oceanic component.

La Plata

Punta del Este

r r e n t

u

Official Border of

C

La Plata River Basin

The northern limit of the oceanic boundary of the region, which

il

Punta Rasta

z

divides it from GIWA region 39 Brazil Current, has been fixed fol owing

r

a

B

the continental limit of La Plata River Basin. Based on hydrologic data

GIWA region 38

in the area, there is an interaction between river freshwater discharges

South Atlantic

Drainage System

(particularly the La Plata River), the Malvinas Current and Brazil Current

a l v i n a s C u r r e n t

M

up to the Florianopolis region in Brazil (Figure 2). This interaction

Península

de Valdes

ranges as far as the area near "Península de Valdes". Therefore, the

© GIWA 2004

limits between GIWA region 38 and 39, regarding the oceanographic

Figure 2

Boundaries between La Plata River Basin, South Atlantic

Drainage System, and GIWA region 39 Brazil Current.

conditions, suppose a permeable character due to migration, dispersion,

space and time variations of the convergence.

Physical characteristics

Table 1

Selected sub-systems for region 38 Patagonian Shelf.

Shared surface or groundwater sub-system

Country

La Plata River Basin

Apa (Paraguay River system)

Brazil and Paraguay

La Plata River Basin is the second largest basin in South America,

Bermejo (Paraguay River system)

Argentina and Bolivia

occupying an area of about 3 100 000 km2 (CIC 1997) and territories

Pilcomayo

Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay

within five countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay

Paraguay

Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay

(Figure 3).

Iguazú (Paraná River system)

Argentina and Brazil

a

s

i

n

San Antonio (Iguazú River system)

Argentina and Brazil

Climate

i

v

e

r B

Paraná

Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay

The Basin comprises several climatic zones as shown in Figure 4. One

l

a

t

a R

Uruguay

Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay

of the most important characteristics of the Basin is the high variation

L

a P

Cuareim (Uruguay River system)

Brazil and Uruguay

in rainfal (Baetghen et al. 2001). Mean annual precipitation ranges

Negro (Uruguay River system)

Brazil and Uruguay

between 1 800 mm along the Brazilian coast, which is subject to

Pepiri Guazú (Uruguay River system)

Argentina and Brazil

marine influence, and 200 mm at the western border of the Basin. The

La Plata River

Argentina and Uruguay

exceptions are some areas associated with the sub-Andean ranges,

Guaraní Aquifer

Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay

where rainfal increases substantial y. Spatial variation of seasonal

Alfa

Argentina and Chile

rainfal regime is also significant. The northern area has a distinct

Chico del sur

Argentina and Chile

seasonal pattern with maximum rainfal during summer, whereas in

Cul en

Argentina and Chile

Chico

Argentina and Chile

the central area seasonal distribution is more uniform, with maximum

Gamma

Argentina and Chile

rainfal in spring and autumn. The amplitude of the annual cycle in

y

s

t

e

m

Gal egos

Argentina and Chile

rainfall decreases from north to south both in absolute and in relative

r

a

i

n

a

g

e S

Grande

Argentina and Chile

terms. Summer rainfall exceeds winter rainfall by almost eight times in

San Martín

Argentina and Chile

the Upper Paraguay and Upper Paraná basins, is twice as great in the

t

l

a

n

t

i

c D

Tierra del Fuego

Argentina and Chile

Middle Paraná, and much less in the south. Since the rivers general y run

S

o

u

t

h A

Colorado

Argentina

from north to south, this rainfall regime contributes to the attenuation

Chubut and Chico

Argentina

of the hydrological seasonal cycle downstream (Baetghen et al. 2001).

Limay, Neuquén and Negro

Argentina

Between the 1970s and the present, the Basin has been under the

Santa Cruz

Argentina

influence of a humid period, which increases annual precipitation.

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

REGIONAL DEFINITION

19

Cuiaba

Cuiaba

Brasilia

Goiania

Pantanal

Taquari

Bolivia

Ver Ladario

de

Capivari

Paranaiba

Negro

Potosi

Ve

Brazil

Gr

r

a

d

n

Campo

e

d

Grand

e

e

São Jose do Rio Preto

Tarija

Tieté

A

Riberao Preto

pa

Mision La Paz

Pa

Par

Bauru

Paraguay r

Paraná

apanem

Patiño

a

a

Piracic

g

aba

u

S

Iva

o

í

a

ro

Campinas

y

c

P

a

Quirquincho

La Estrella

ilc

ba

om

São Paulo

a

S. S. de Jujuy

yo

Yema Lag

Salta

Bermejo Blanca Lag

Asuncion

Formosa

Iguazú

Curitiba

Uniao do

Posadas

UruguayVictoria

Resistencia

Pepiri Guazu

Main wetlands

Sgo. del Estero

Corrientes

Encarnación

Ibera

Main reservoirs

In operation

Salado

Under construction

Ibicui

Planned

Monte Caseros

Quarai

Cuar

Artigas

eim

0

500 Kilometres

Argentina

Salto

Santa Fe

Paraná

Uruguay

Tercero

o

Negr

Rosario

Cuarto

Yi

Zárate

Campana

Colonia

Buenos Aires

Montevideo

Sal

Punta del Este

ado

La Plata

Magdalena

2

3

a

. Vallimanc

4s

4sd

1

4d

© GIWA 2004

5dw

Figure 3

The drainage basins of the tributaries comprising

La Plata River Basin.

6sh

H

(Source: ANEEL 2000)

6h

Climate zones

7

1: Rainy equatorial

2: Monsoon and littoral alisios winds

5d

8h

3: Dry and wet tropical

The average annual temperature in the Basin ranges from 15°C in the

8sh

4d: Desert tropical

south to more than 25°C in the northwest. In winter, there is a well

4s: Semi arid tropical

4sd: Semi desert tropical

established north-south gradient in monthly-mean temperatures. In

5d: Desert sub-tropical

5dw: Western coasts desert dry sub-tropical

July, the mean temperature in the southern area is between 8°C and

6h: Humid sub-tropical

10°C, while in the northwest of the Basin, it is higher than 20°C. In

6sh: Sub-humid sub-tropical

7: Mediterranean

summer, the gradient is governed by the land-ocean distribution. In

9

8: Western coast maritme

8h: Western coast maritime humid

January, the mean maximum temperatures exceed 27.5°C in the Chaco

8

8sh: Western coast maritime sub-humid

region and in western Argentina, while they are lower than 22.5°C in

9: Dry of middle latidude

H: High altitude climate

© GIWA 2004

the coastal areas of southern Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina (Baetghen

Figure 4

Climate zones.

et al. 2001).

(Source: CIAT 1998, Strahler & Strahler 1989))

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

Biotopes

savannah of pastures has developed. The Pantanal and the Paraná

The main biotopes of the Basin are the forests and the savannahs.

deltas are important flooding pastures; the latter interrupts the Pampa,

The climate and the variations in topography and soil influence these

a large gramineous pasture (Dinerstein et al. 1995). There are large

biotopes, which are also highly transformed by human intervention.

numbers of protected areas that were created to preserve the remains

The remains of the sub-tropical conifer forest, associated with humid

of the diverse biotypes and to protect biodiversity.

tropical forest, are located in the Lower Iguazú Basin. There is another

humid tropical forest (regional y known as "Yungas") located in the

Land use

eastern Andean mountain sides. Final y, the Atlantic forest of the

Agriculture is the main land activity in the Basin (Figure 6). By the end

Brazilian littoral is a humid broad-leaf forest (Dinerstein et al. 1995).

of the 1960s, a gradual expansion of the farming border and changes in

the main crops was registered in the Brazilian and Argentinean sectors

In the central area of the Basin are the Chaco savannahs, an ecoregion

of the Basin. For example, until 1970, most of the Paraná state (Brazil)

shared by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia and dominated

and a large part of São Paulo state (Brazil) cultivation areas were used for

by deciduous vegetation (Figure 5). The Cerrado, a savannah-

coffee. Large areas of these plantations were destroyed by fire, causing

forest complex composed of several types of habitats and natural

major financial losses. Subsequently, annual crops such as corn and

communities, occupies the northern area (between 15°-22° S and

soybean replaced coffee. Meanwhile, in the Argentinean sector, the

58°-59° W). The Cerrado is more open along the São Lorenço, Taquari

main rural areas also changed crop and agricultural systems. At the

and Paraguay rivers. Final y, in Uruguay and southern Brazil, a humid

end of the 1960s, the annual wheat crop was substituted by a wheat and

soybean rotation system. The same system occurs in Paraguay, where

the soybean is the main crop and on the increase due to the application

of new technologies and the expansion of productive areas.

Pantanal

Cerrado

Central

Andean

puna

Chaco

savannahs

Humid

Chaco

Cordoba montane

savannahs

Uruguayan

steppe

savannahs

ndean A

Argentina Espinal

e

rn

S

outh

Monte

Ecoregions

Flooded grasslands

Montane grasslands

Land cover

Snow, ice, glaciers, and rock

Steppes of

Barren

Patagonia

Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests

Tundra

Temperate coniferous forests

Cropland

Temperate grasslands,

Forest

savannahs, and shrublands

Tropical and sub-tropical

Developed

dry broadleaf forests

Grassland

Tropical and sub-tropical grasslands,

savannahs, and shrublands

Savannah

Tropical and sub-tropical

moist broadleaf forests

Shrubland

© GIWA 2004

© GIWA 2004

Figure 5

Ecoregions.

Figure 6

Land cover.

(Source: Olson et al. 2001)

(Source: Data from Loveland et al. 2000)

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

Wheat, barley and oats are the main crops in Uruguay. Rice is also

cultivated in southern Brazil and eastern Argentina. This crop places

a strong demand on the water resources of the Uruguay River

Itumbiara

and its tributaries, for instance, about 13% of the Ibicuy river flow

Cachoeira Dourada

Emboracao

(Tucci & Clarke 1998).

Bolivia

Sao Simao

Ilha Solteira

Agua Vermelha

Jupia

Estreito

Final y, regarding livestock farming, bovines predominate in the Basin.

Tres Irmaos

Marimbondo

Paraguay

In Argentina, more than 70% of the country's bovines are raised within

Brazil

Furnas

Capivara

the La Plata River Basin. Likewise in Brazil, about 10% of the country's

Itaipu

bovines and more than 80% of Uruguay's livestock are raised within the

Acaray

Salto Osorio

Argentina

Basin. In Paraguay, 90% of the agricultural production is livestock.

Yacyreta

Salto Grande

Rivers

Uruguay

The Paraná and Uruguay rivers col ect all water from the Basin, draining

Rincon del Bonete

into La Plata River (Figure 3). The Paraná River, formed at the junction

Baygorria

of the Paranaiba River and Grande River in Brazil, receives water from

numerous large tributaries. Some major sub-basins are distinguished,

0

500 Kilometres

as are those corresponding to the Paraguay, Pilcomayo, Bermejo

© GIWA 2004

and Iguazú rivers (Table 2 and Figure 3). Table 3 shows the chemical

Figure 7

Main reservoirs in La Plata River Basin.

characteristics of the main rivers in the La Plata Basin.

(Source: ANEEL 2000)

The Upper Paraná River spreads over the Brazilian Southern Plateau,

Table 2

Main rivers of La Plata River Basin.

River

Basin area

while the Lower Paraná River traverses an area of plains. The system

(km2)

Length (km)

Average discharge (m3/s) Average depth (m)

Uruguay

440 000

1 850

4 500

ND

is characterised by large mean annual flows, resulting from heavy

Paraguay

1 095 000

2 415

3 8101

5

precipitation in the upper Basin. The width and bed morphology

Paraná

1 600 000

2 570

17 1402

15-50

changes greatly along the course. Several important wetlands, such

Iguazú

61 000

1 320

1 540

ND

as the Iberá marshes, Submeridional Lowlands, Middle Paraná alluvial

Bermejo

120 000

1 780

550

1.3

val ey and the Paraná Delta in Argentina, are associated with the Paraná

Pilcomayo

272 000

1 125

195

ND

River (Canevari et al. 1998).

La Plata

3 100 000

270

23 000-28 000

10

Notes: 1Paraguay at Puerto Bermejo. 2Paraná at Corrientes. ND = No data. (Source: Framiñan &

Brown 1996, Giacosa et al. 1997, SSRH 2002 and ANEEL, SRH/MMA, IBAMA 1996)

In Brazil, the Paraná River and its main tributaries (Parapanema and

Table 3

Main chemical characteristics of La Plata Basin rivers.

Tietê) are mainly used to generate hydropower and a large number of

Nutrient concentration (mg/l)

Turbidity

reservoirs (Figure 7) have been built. Itaipú Dam (Brazil and Paraguay)

River

pH

Nitrite

Nitrate

Phosphate

(NTU)

stands out and, together with Yacyretá Dam (Argentina and Paraguay),

Upper Uruguay (Iraí Station)

0.007

1.61

0.125

7.2

18

they constitute examples of joint developments by riparian countries in

Middle Uruguay (Uruguaiana)

0.050

1.5

0.36

7.1

51

the Basin. In Argentina, the Middle and Lower Paraná river reaches are

Lower Uruguay (Paysandú)

0.01

3.5

ND

7.0

34

important waterways and their shores host large urban settlements and

Upper Paraguay (Porto Murtinho)

0.02

0.29

0.01

7.5

60

Middle and Lower Paraguay

major industrial activities. In both countries, the Paraná River is used for

0.009

0.91

0.025

7.2

81

(Puerto Pilcomayo)

freshwater supply, industrial use, fishing, recreational activities and as a

Upper Paraná (Guaira)

0.001

0.21

0.029

7.2

14.2

recipient of domestic and industrial effluents.

Middle Paraná (Corrientes)

0.05

0.178

0.198

7.3

243.7

Lower Paraná (Rosario)

0.06

1.0

ND

7.3

120

Iguazú (Foz do Iguazú)

0.63

ND

0.02

7.5

17

The Uruguay River Basin has also its upper areas on the Brazilian Plateau

Bermejo

0.15

0.001

0.03

6.5

554 (mg/l)

and the lower ones in the plains. The Uruguay River rises at Serra do Mar

Pilcomayo (Tres Pozos)

0.066

0.002

ND

7.7

55

(Brazil) and has a graded cross section due to its geological formation

La Plata (Coastal border from San

0.01-0.5

4.5

0.03-0.14

7-7.4

10 - 200

which presents some significant narrow stretches along its main course

Fernando to Magdalena)

Note: ND = No Data. (Source: CIC 1997)

(Coimbra Moreira et al. 2002). Its flow regime shows considerable

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 38 PATAGONIAN SHELF

REGIONAL DEFINITION

23

seasonal variability. The Uruguay River is utilised for various purposes

The Bermejo River Basin has sectors with very active sediment

by the riparian countries. Its most important use is Salto Grande

generation processes, mainly in the upper basin. The Bermejo River

hydroelectric power plant (shared by Argentina and Uruguay, Figure 7),

rises in Real ranges (Bolivia) and in the sub-Andean ranges areas of Salta

which was completed in early 1980s. The River is navigable downstream

and Jujuy provinces (Argentina). After entering the Chaco plain (lower

of the dam for about 340 km and it supplies water to irrigated rice fields

basin), the River dramatical y reduces its slope and looses its capacity to

in Uruguay and Brazil (Yelpo & Serrentino 2000). The Cuareim (or Quarai)

carry sediment, which results in the deposition of part of the suspended

and Negro rivers are both transboundary water bodies and are the main

sediments. Despite this fact, the Bermejo River contributes with over

tributaries of the Uruguay River left margin.

80% of the suspended sediments transported by the Paraná River into

the La Plata River (CCBermejo 2000). Its water is used to irrigate farming

The Paraguay River, the main tributary of Paraná River and its basin,

areas and for human and livestock consumption, both in Bolivia and

spreads over an area of plains. It rises to the north, in the Parecis ranges

Argentina. There are some wetlands associated with the Bermejo River

(Brazil), which divides the La Plata River Basin and the Amazon River

system, such as Quirquincho swamps and Yema Lagoon in Argentina

Basin. A major feature of the Upper Paraguay Basin is the Pantanal,

(Canevari et al. 1998).

the world's largest wetland. The Pantanal is a huge floodplain, 770 km

long with an area of about 80 000 km2 (high water season), that

The La Plata River is a funnel-shaped coastal plain tidal river. It is oriented

serves as a reservoir which regulates the Paraguay-Paraná regime

in a northwest-southeast direction. Its mouth, defined by a line joining

(Canevari et al. 1998). Downstream of the Pantanal, the Paraguay River

Punta Rasa (Argentina) and Punta del Este (Uruguay) is about 230 km

flows between high natural embankments, forming multiple meanders

wide. Based on its hydrodynamics and morphology, the La Plata River

next to the mouth. The Paraguay River is mainly used in Brazil and

may be divided into two main areas: the inner area, which has a two-

Paraguay as a waterway, which also serves Bolivia.

dimensional flow; and the outer area, which has a three-dimensional

flow resulting from the widening of the River towards its mouth. The

The Iguazú (or Iguaçú) River Basin spreads on the Brazilian Plateau.

interaction of nutrient rich freshwater with coastal marine water in the

The Iguazú River rises in Serra do Mar (Brazil) and because of the relief,

outer area supports the spawning and nursery area of several important

the riverbed presents sharp changes in gradient and narrow val eys.

fishery resources (Framiñan & Brown 1996). On the Argentinean coast,

There are many waterfalls, such as the renowned Iguazú Falls, and

the La Plata River waters are used for human consumption and as a

rapids along its course. Such features indicate the large hydropower

disposal site for urban and industrial wastes of Buenos Aires and its