MA

A P : G

ND S IW

UB A R

SY E

S G

T IO

EM NS

S

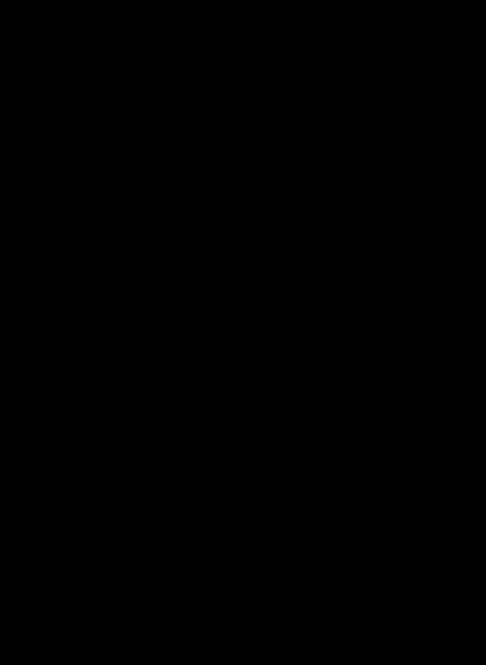

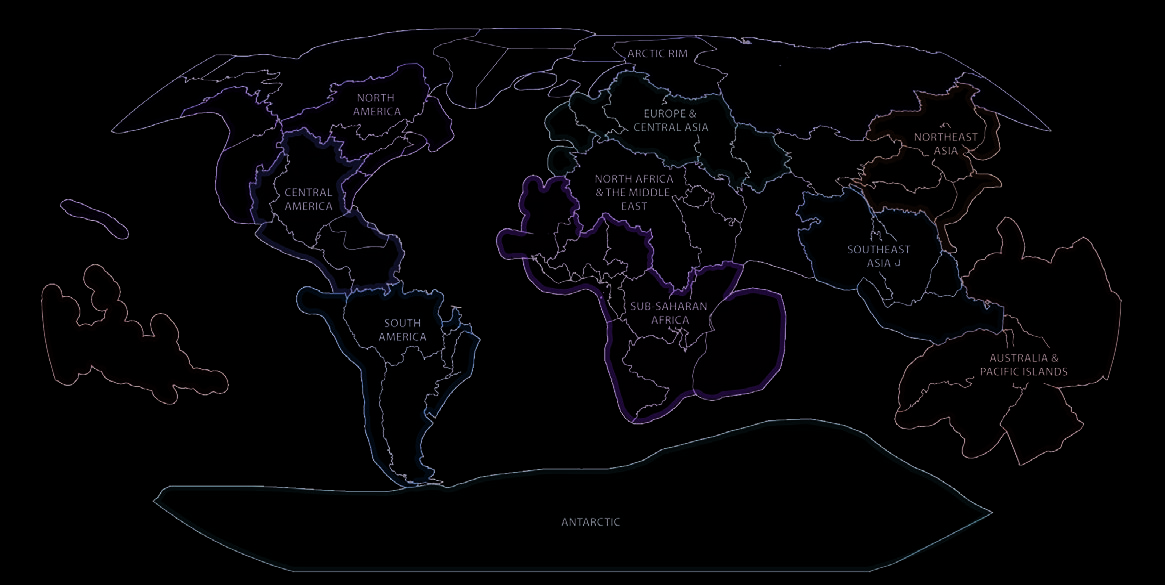

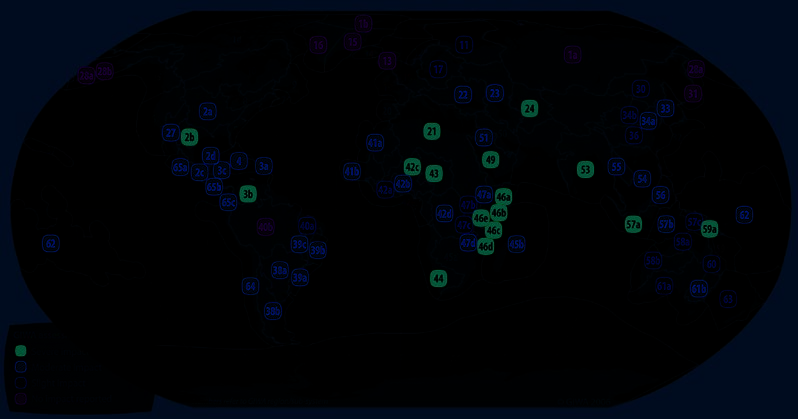

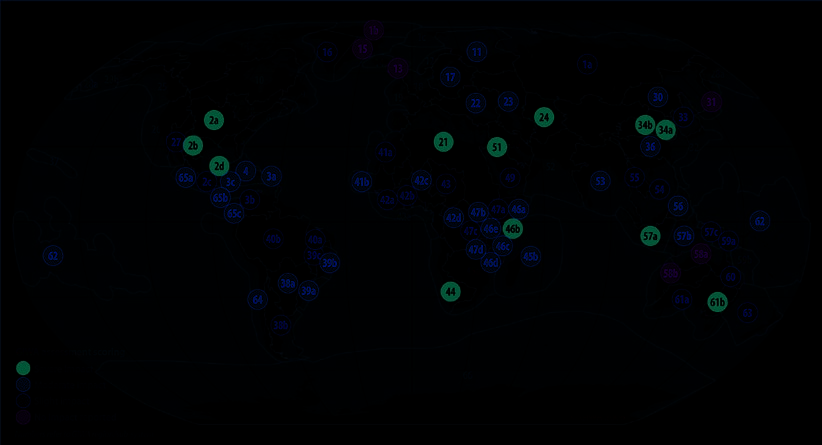

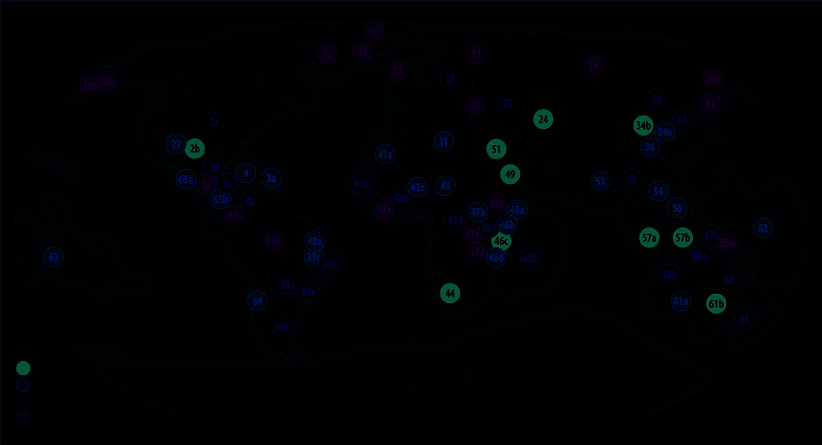

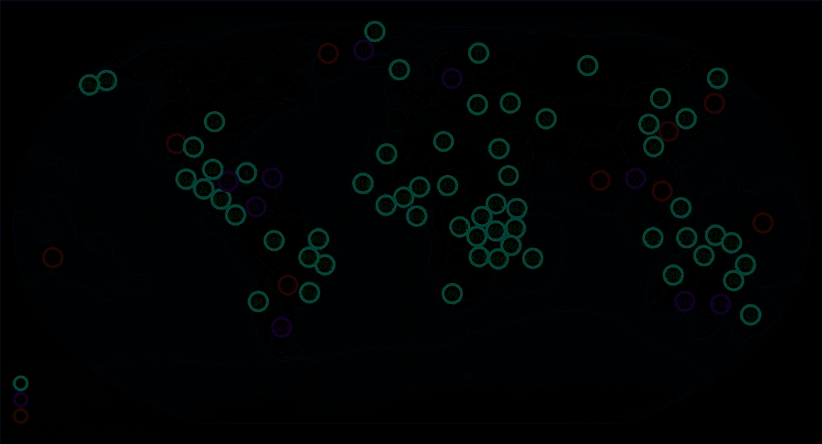

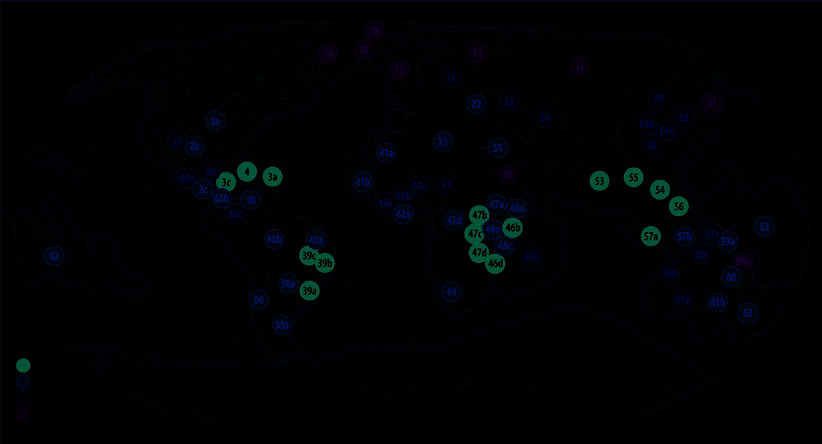

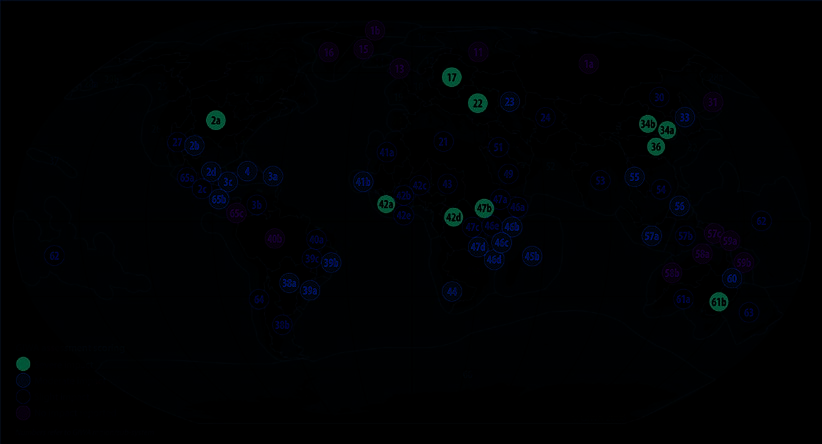

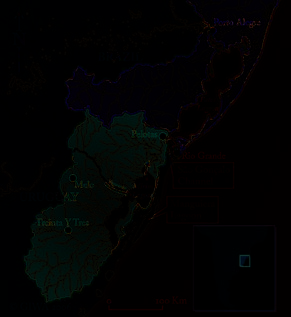

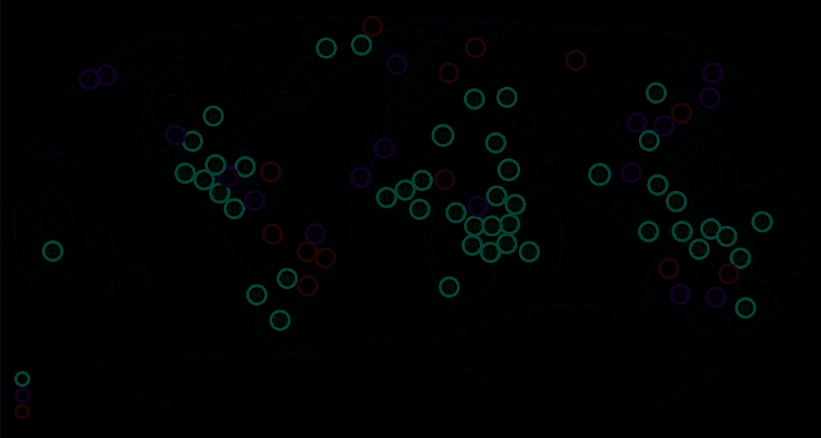

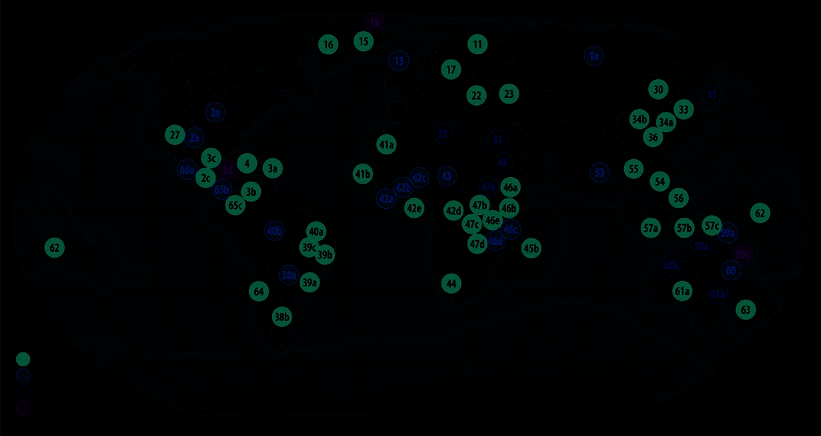

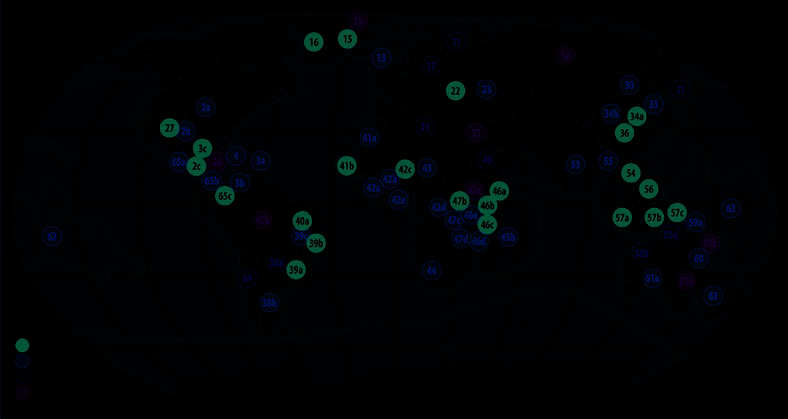

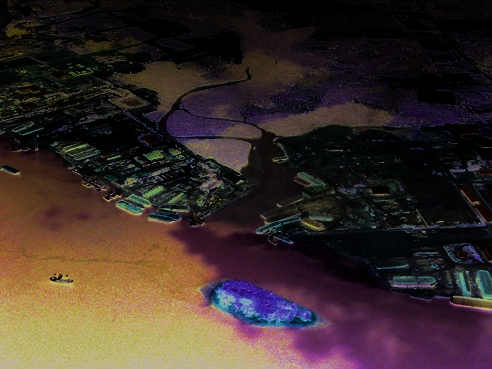

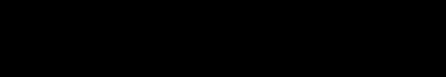

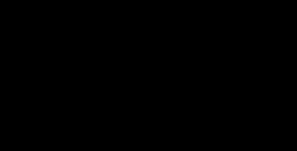

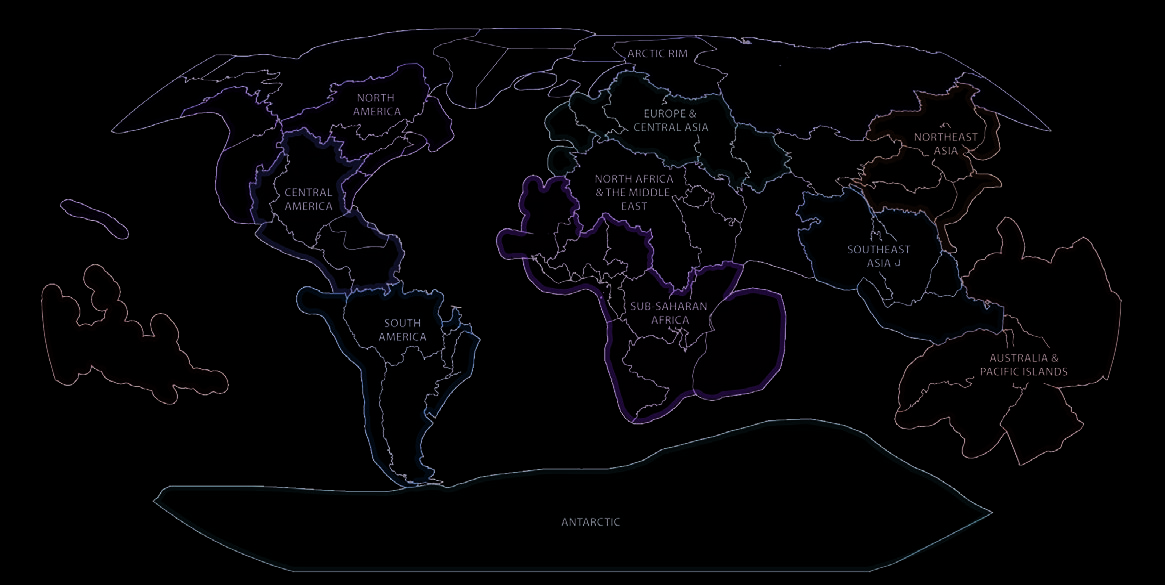

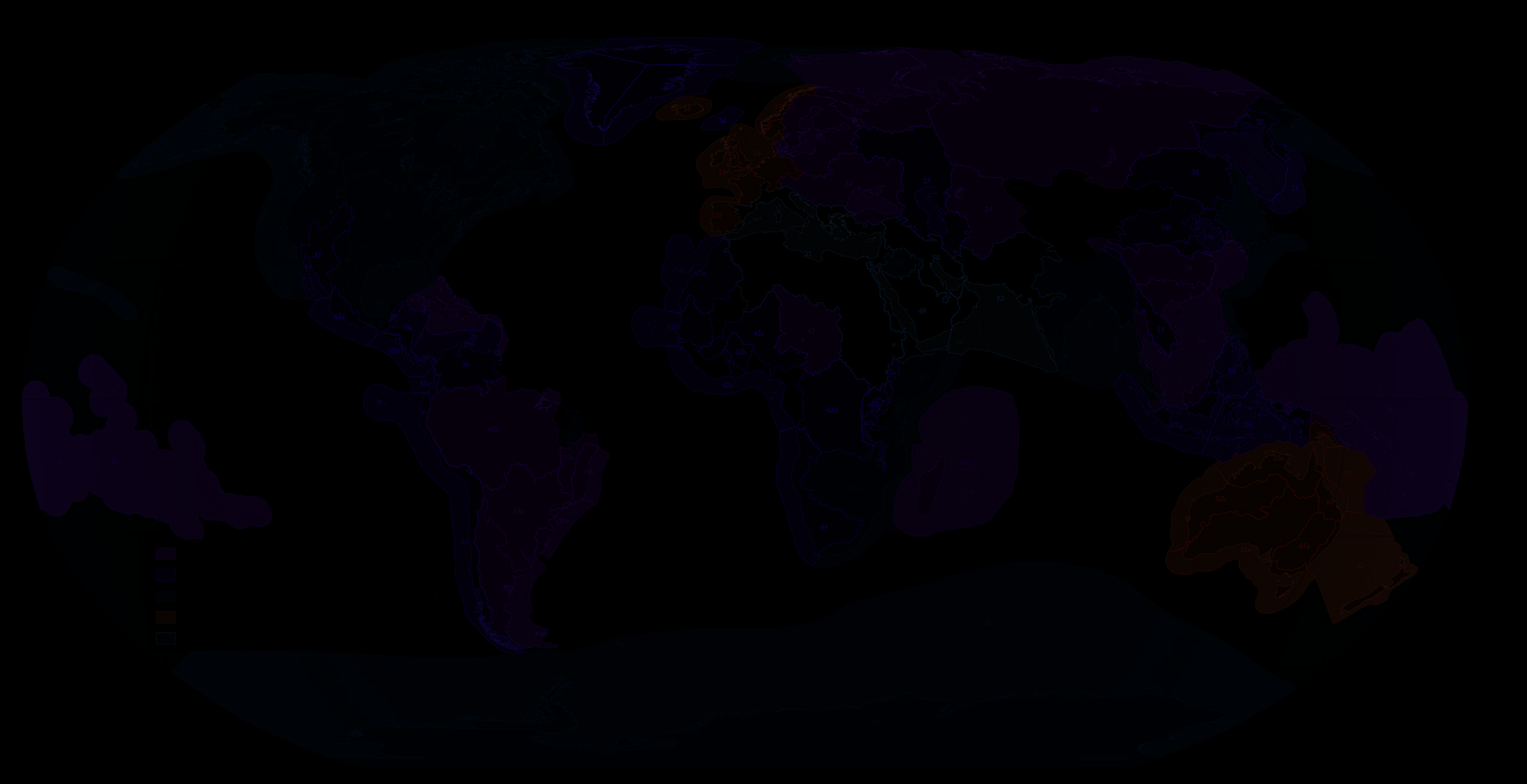

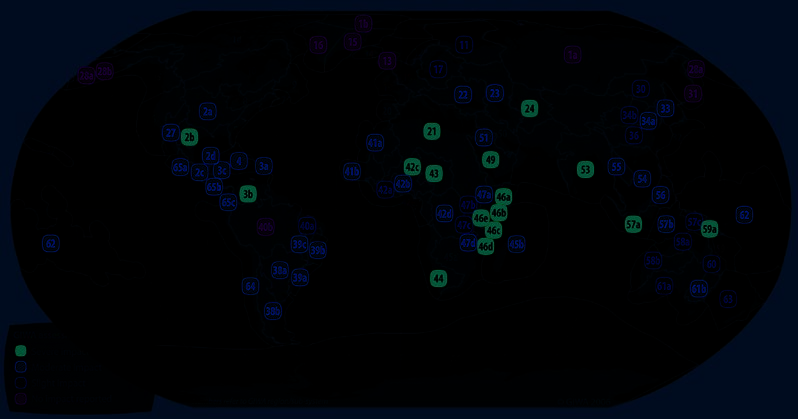

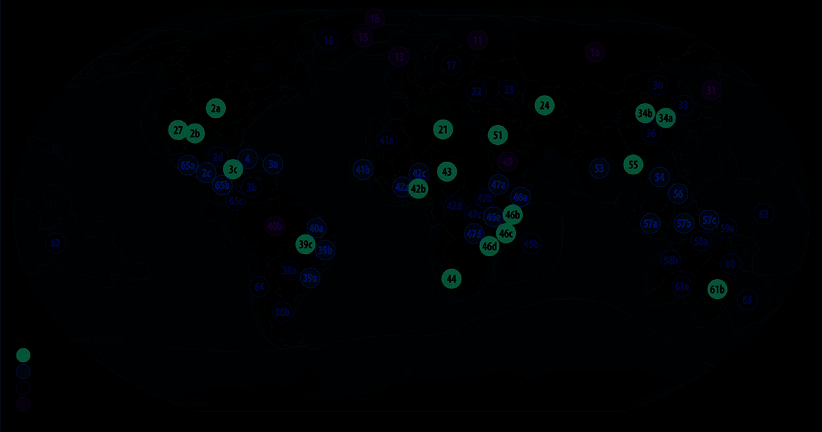

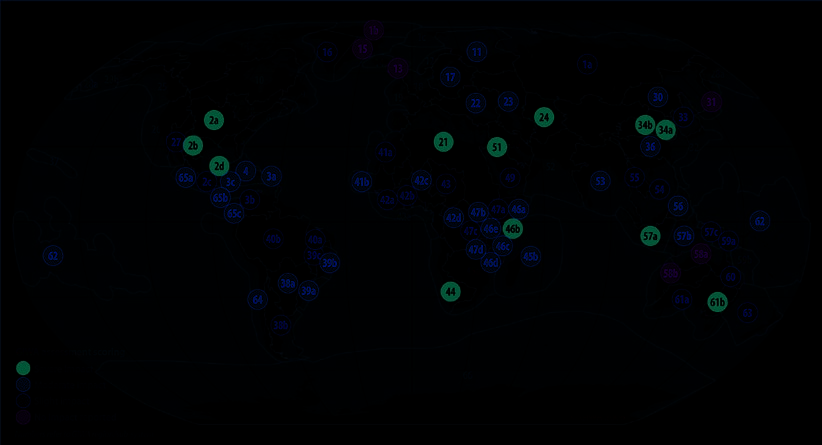

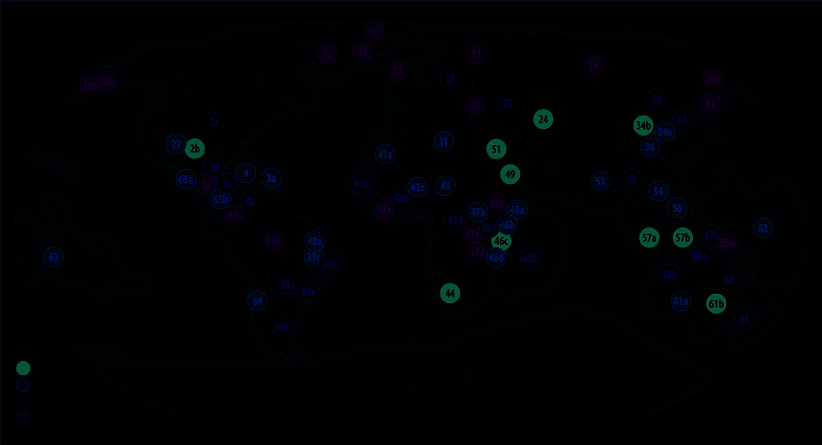

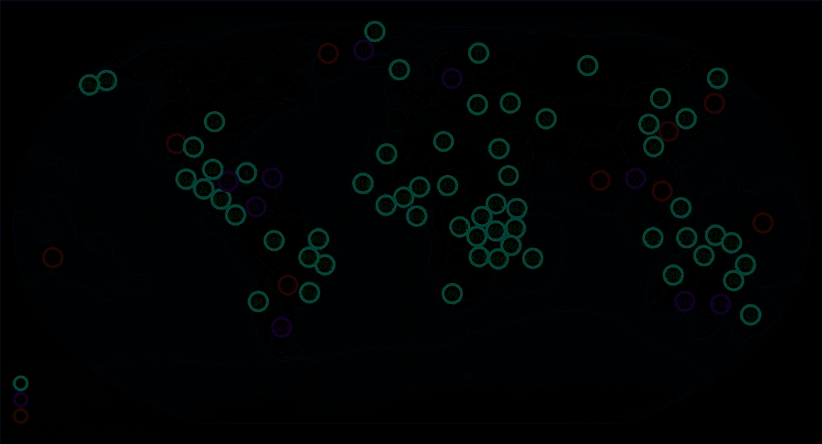

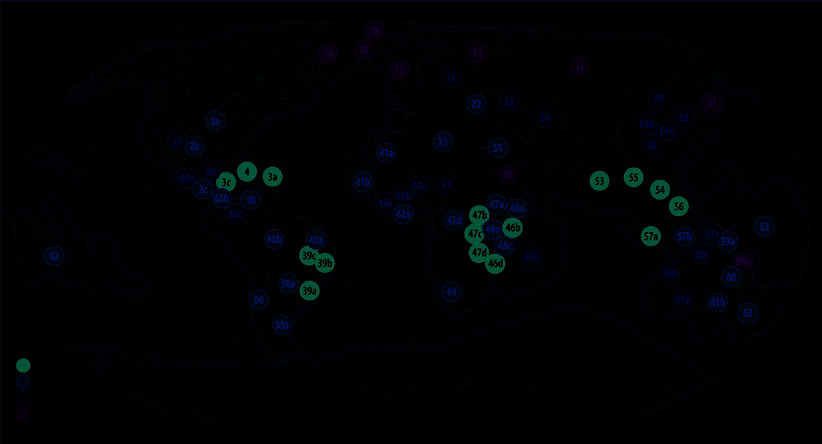

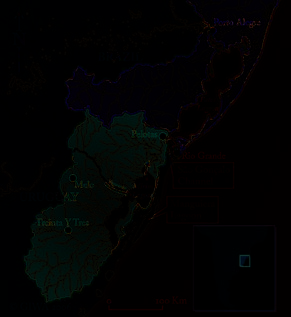

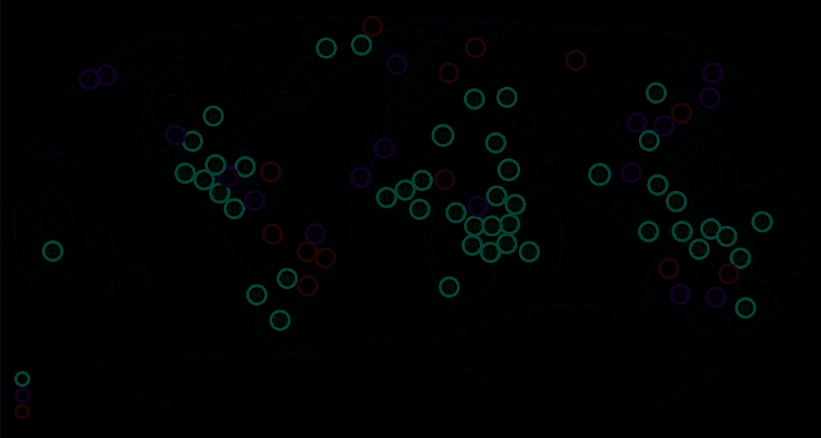

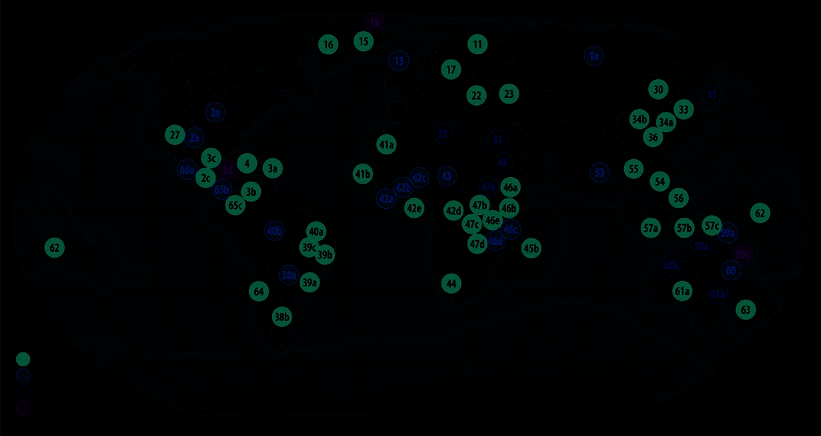

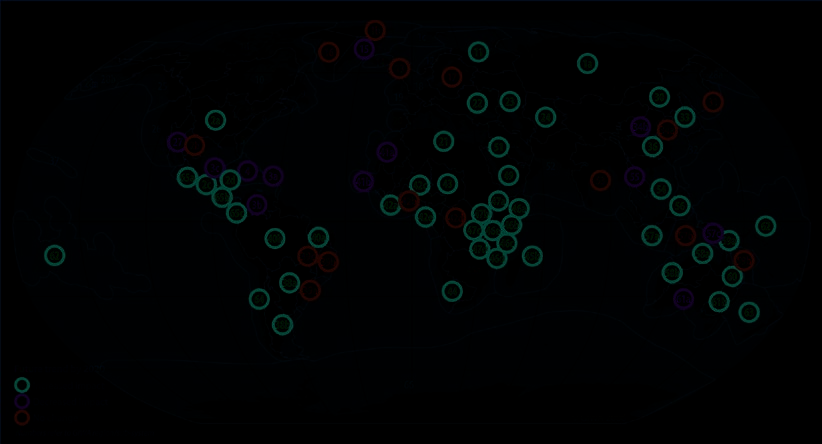

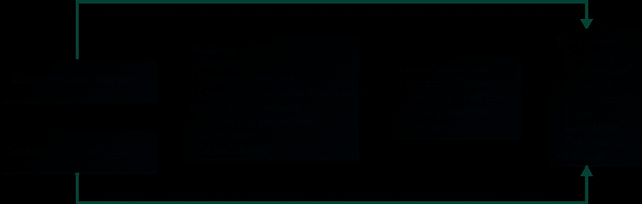

GIWA MEGA REGIONS

GLOBAL INTERNATIONAL

WATERS ASSESSMENT

AREA SHADING BY MEGA REGION

Arctic Rim

27 Gulf of California*

Northeast Asia

1a Russian Arctic*

65a Eastern Equatorial Pacific (Southwest Mexico)*

30 Sea of Okhotsk*

1b Arctic Greenland*

65b Eastern Equatorial Pacific (Central Equatorial Pacific)*

31 Oyashio Current*

1c Arctic European/Atlantic

65c Eastern Equatorial Pacific (Pacific Colombian)*

32 Kuroshio Current

1d Arctic North American

33 Sea of Japan*

11 Barents Sea*

34a Yel ow Sea (Yel ow Sea)*

12 Norwegian Sea

South America

34b Yel ow Sea (Bohai Sea)*

13 Faroe Plateau*

38a Patagonian Shelf (La Plata River Basin)*

36 East China Sea*

14 Iceland Shelf

38b Patagonian Shelf (South Atlantic Drainage System)*

15 East Greenland Shelf*

39a Brazil Current (South/Southeast Atlantic Basins)*

16 West Greenland Shelf*

39b Brazil Current (East Atlantic Basins)*

28a Bering Sea (West Bering Sea)*

39c Brazil Current (São Francisco River Basin)*

Southeast Asia

28b Bering Sea (East Bering Sea)*

40a Northeast Brazil Shelf*

40b Amazon*

53 Bay of Bengal*

64 Humboldt Current*

54 South China Sea*

Europe & Central Asia

55 Mekong River*

56 Sulu-Celebes Sea*

17 Baltic Sea*

57a Indonesian Seas (Sunda)*

18 North Sea

Sub-Saharan Africa

57b Indonesian Seas (Wal acea)*

19 Celtic-Biscay Shelf

41a Canary Current (North)*

57c Indonesian Seas (Sahul)*

20 Iberian Coastal Sea

41b Canary Current (South)*

22 Black Sea*

42a Guinea Current (Comoe Basin)*

23 Caspian Sea*

42b Guinea Current (Volta Basin)*

Australia & Pacific Islands

24 Aral Sea*

42c Guinea Current (Niger Basin)*

42d Guinea Current (Congo Basin)*

58a North Australian Shelf (Wet Tropics)*

42e Guinea Current LME*

58b North Australian Shelf (Dry Tropics)*

North America

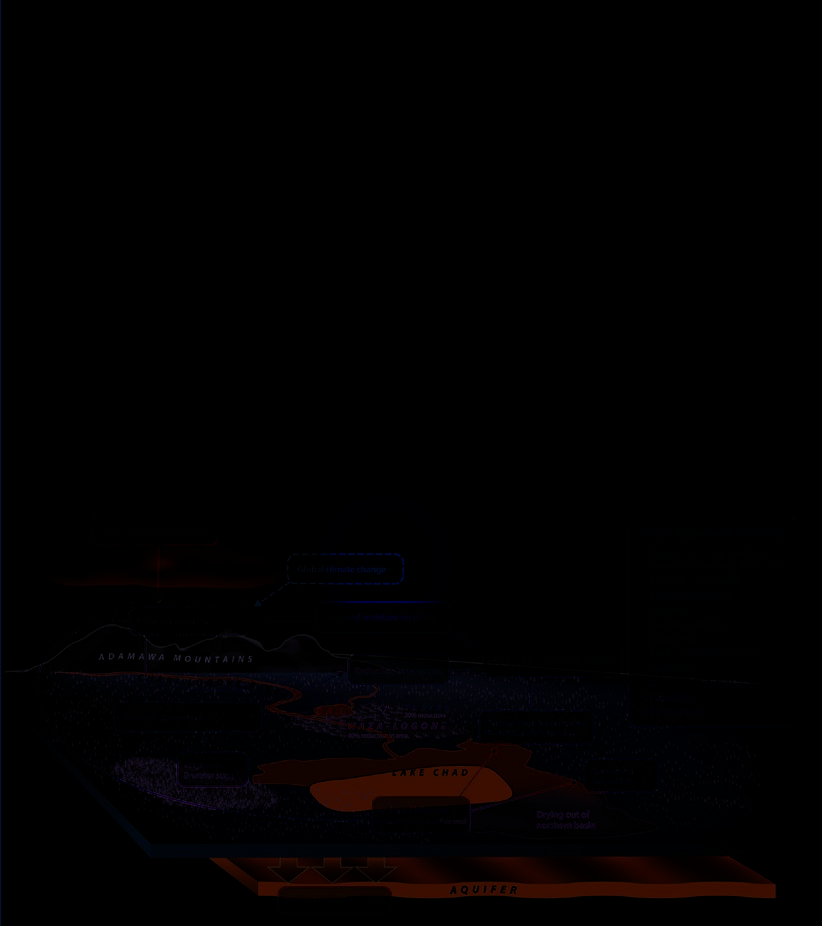

43 Lake Chad*

59a Coral Sea Basin (South PNG and Papua)*

59b Coral Sea Basin (Coral Sea)*

5

Southeast Shelf

44 Benguela Current*

60 Great Barrier Reef*

6 Northeast Shelf

45a Agulhas Current

45b Indian Ocean Islands*

61a Great Australian Bight*

InCthealrenngesa tto

7

Scotian Shelf

61b Great Australian Bight (Muray Darling Basin)*

8 Gulf of St Lawrence

46a Somali Coastal Current (Juba/Shebel e)*

62 Pacific Islands*

9 Newfoundland Shelf

46b Somali Coastal Current (Tana/Athi/Sabaki)*

63 Tasman Sea*

10 Baffin Bay, Labrador Sea, Canadian Archipelago

46c Somali Coastal Current (Wami/Ruvu/Pangani)*

25 Gulf of Alaska

46d Somali Coastal Current (Rufiji/Ruvuma)*

26 California Current

46e Somali Coastal Current (Lake Jipe/Chala)*

Antarctic

37 Hawai an Archipelago

47a East African Rift Val ey Lakes (Lake Turkana)*

66 Antarctic

Regional Asiso

ess n

me a

ntsl W

in a Gl a

ob t

al e

Perrss

pective

47b East African Rift Val ey Lakes (Lake Victoria)*

47c East African Rift Val ey Lakes (Lake Tanganyika)*

Central America

47d East African Rift Val ey Lakes (Lake Malawi)*

2a Gulf of Mexico (Mississippi River)*

2b Gulf of Mexico (Rio Grande/Rio Bravo)*

2c Gulf of Mexico (Usumacinta/Grijalva)*

North Africa & Middle East

2d Gulf of Mexico (Rio Hondo/Chetumal Bay)*

21 North Africa and Nile River Basin

3a Caribbean Sea (Small Islands)*

49 Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

3b Caribbean Sea (Orinoco/Magdalena/Catatumbo)*

50 Euphrates and Tigris River Basin

3c Caribbean Sea (Central America/Mexico)*

51 Jordan*

4 Caribbean Islands*

52 Arabian Sea

THE GIWA FINAL REPORT

* Assessed by GIWA.

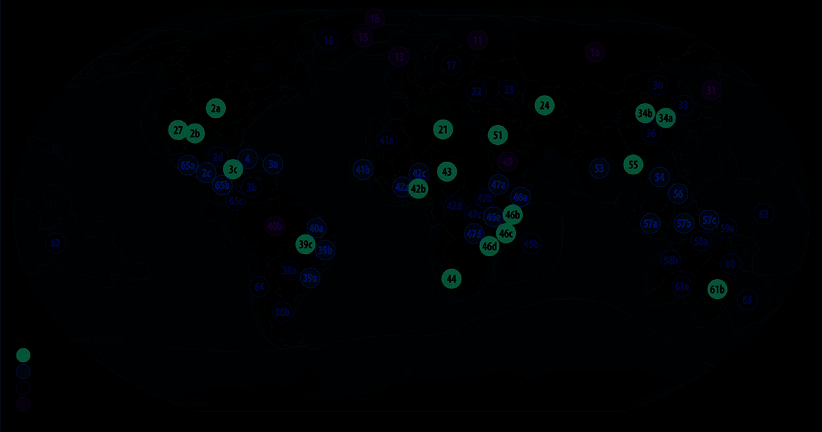

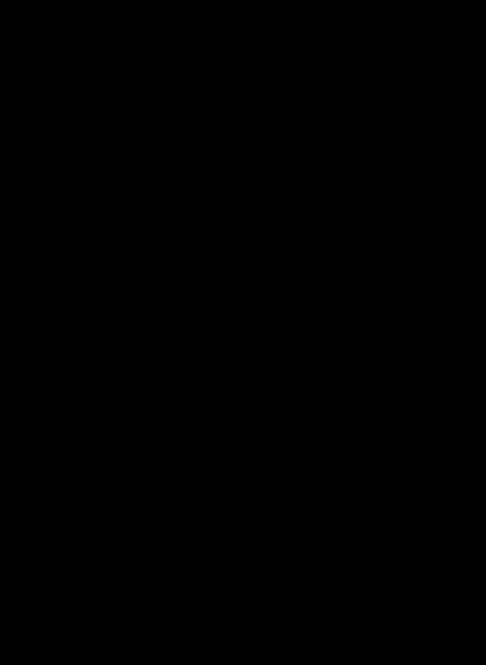

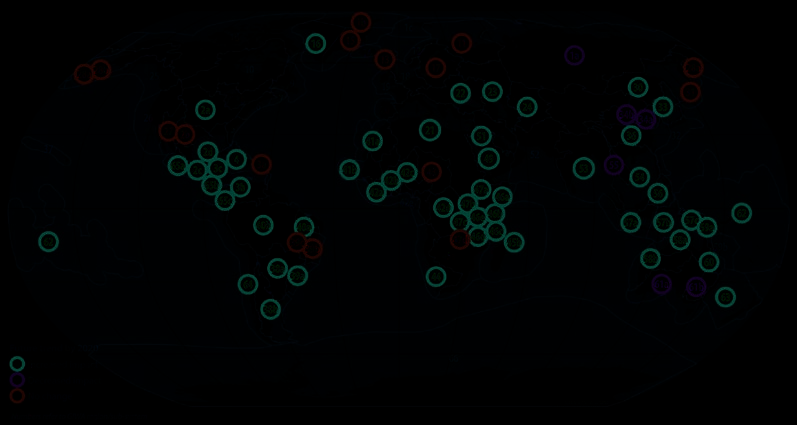

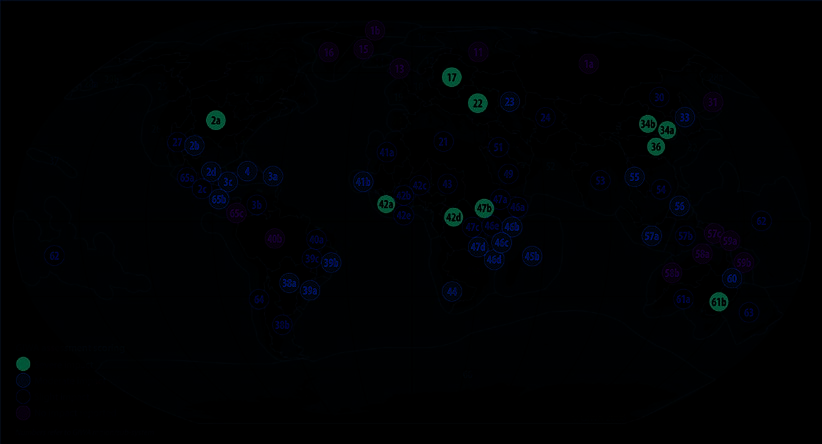

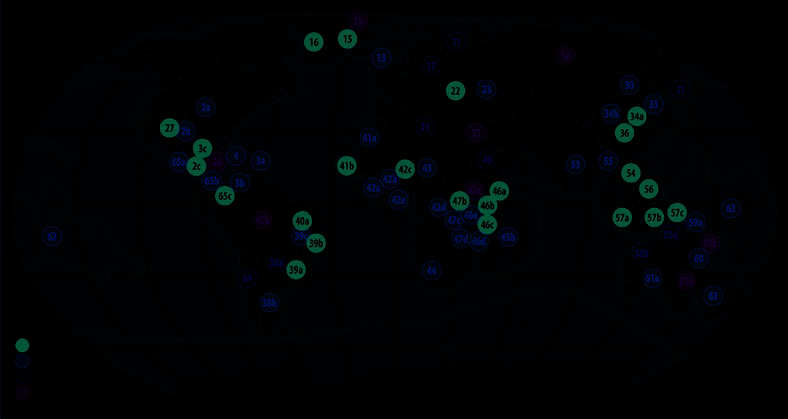

GIWA REGIONS AND SUBSYSTEMS

1a Russian Arctic

10 Baffin Bay, Labrador Sea, Canadian Archipelago 27 Gulf of California

40b Amazon

47a East African Rift Val ey Lakes (Lake Turkana)

59a Coral Sea Basin (South PNG and Papua)

1b Arctic Greenland

11 Barents Sea

28a Bering Sea (West Bering Sea)

41a Canary Current (North)

47b East African Rift Val ey Lakes (Lake Victoria)

59b Coral Sea Basin (Coral Sea)

1c Arctic European/Atlantic

12 Norwegian Sea

28b Bering Sea (East Bering Sea)

41b Canary Current (South)

47c East African Rift Val ey Lakes (Lake Tanganyika) 60 Great Barrier Reef

1d Arctic North American

13 Faroe Plateau

30 Sea of Okhotsk

42a Guinea Current (Comoe Basin)

47d East African Rift Val ey Lakes (Lake Malawi)

61a Great Australian Bight

2a Gulf of Mexico (Mississippi River)

14 Iceland Shelf

31 Oyashio Current

42b Guinea Current (Volta Basin)

49 Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

61b Great Australian Bight (Muray Darling Basin)

2b Gulf of Mexico (Rio Grande/Rio Bravo)

15 East Greenland Shelf

32 Kuroshio Current

42c Guinea Current (Niger Basin)

50 e Gulf

62 Pacific Islands

2c Gulf of Mexico (Usumacinta/Grijalva)

16 West Greenland Shelf

33 Sea of Japan

42d Guinea Current (Congo Basin)

51 Jordan

63 Tasman Sea

2d Gulf of Mexico (Rio Hondo/Chetumal Bay)

17 Baltic Sea

34a Yel ow Sea (Yel ow Sea)

42e Guinea Current LME

52 Arabian Sea

64 Humboldt Current

3a Caribbean Sea (Small Islands)

18 North Sea

34b Yel ow Sea (Bohai Sea)

43 Lake Chad

53 Bay of Bengal

65a Eastern Equatorial Pacific (Southwest Mexico)

3b Caribbean Sea (Orinoco/Magdalena/Catatumbo) 19 Celtic-Biscay Shelf

36 East China Sea

44 Benguela Current

54 South China Sea

65b Eastern Equatorial Pacific (Central Equatorial Pacific)

3c Caribbean Sea (Central America/Mexico)

20 Iberian Coastal Sea

37 Hawai an Archipelago

45a Agulhas Current

55 Mekong River

65c Eastern Equatorial Pacific (Pacific Colombian)

4 Caribbean Islands

21 North Africa and Nile River Basin

38a Patagonian Shelf (La Plata River Basin)

45b Indian Ocean Islands

56 Sulu-Celebes Sea

66 Antarctic

5 Southeast Shelf

22 Black Sea

38b Patagonian Shelf (South Atlantic Drainage System) 46a Somali Coastal Current (Juba/Shebel e)

57a Indonesian Seas (Sunda)

6 Northeast Shelf

23 Caspian Sea

39a Brazil Current (South/Southeast Atlantic Basins) 46b Somali Coastal Current (Tana/Athi/Sabaki)

57b Indonesian Seas (Wal acea)

7 Scotian Shelf

24 Aral Sea

39b Brazil Current (East Atlantic Basins)

46c Somali Coastal Current (Wami/Ruvu/Pangani)

57c Indonesian Seas (Sahul)

8 Gulf of St Lawrence

25 Gulf of Alaska

39c Brazil Current (São Francisco River Basin)

46d Somali Coastal Current (Rufiji/Ruvuma)

58a North Australian Shelf (Wet Tropics)

9 Newfoundland Shelf

26 California Current

40a Northeast Brazil Shelf

46e Somali Coastal Current (Lake Jipe/Chala)

58b North Australian Shelf (Dry Tropics)

GLOBAL INTERNATIONAL

WATERS ASSESSMENT

InCthealenges to

Re r

gi n

onaa

l t

Asiso

ess n

me a

ntsl W

in a Gl a

ob t

al e

P r

erss

pective

THE GIWA FINAL REPORT

CONTENTS

3

Global International Waters Assessment

Chal enges to International Waters Regional Assessments in a Global Perspective

Published by the United Nations Environment Programme in collaboration with

GEF, the University of Kalmar and the Municipality of Kalmar, Sweden, and the

Governments of Sweden, Finland, and Norway.

© 2006 United Nations Environment Programme

ISBN 91-89584-47-3

UNEP/GCSS.IX/INF/9

To obtain copies of this publication or further information, please contact:

Division of Early Warning and Assessment

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552

Nairobi 00100, Kenya

Tel: +254 20 762-4299

Fax: +254 20 762-4269

Email: dewainfo@unep.org

is publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational

or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for

resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in

writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Applications for such

permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be

addressed to the Director, DCPI, UNEP, P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, Kenya.

CITATION

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2006. Chal enges to International Waters Regional Assessments in a Global

Perspective. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, Kenya.

DISCLAIMER

e views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect those of UNEP. e designations employed and the presentations do no imply

the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating agencies

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or areas or its authority, or

concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

is publication has been peer-reviewed and the information herein is believed to be

reliable, but the publisher does not warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Printed and bound in Kalmar, Sweden by Sunds Tryck Öland AB.

Printed on recycled paper.

CONTENTS

3

Contents

PREFACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

FRESHWATER SHORTAGE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Environmental and socio-economic impacts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Root causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Policy relevant conclusions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

POLLUTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Environmental and socio-economic impacts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Root causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Policy relevant conclusions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

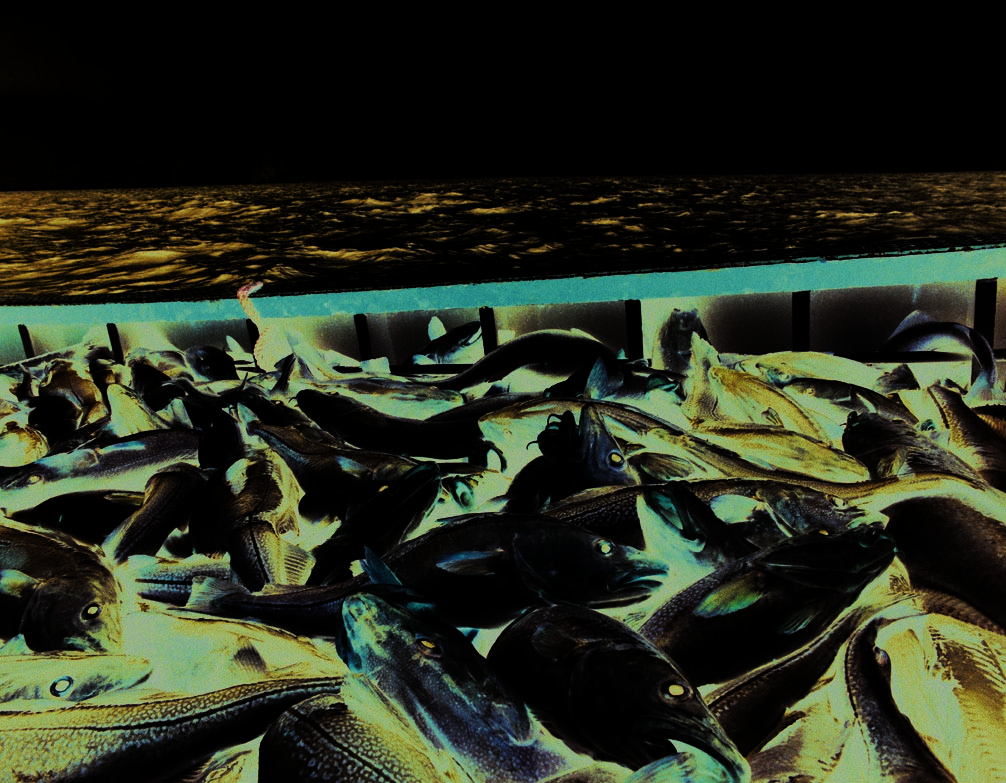

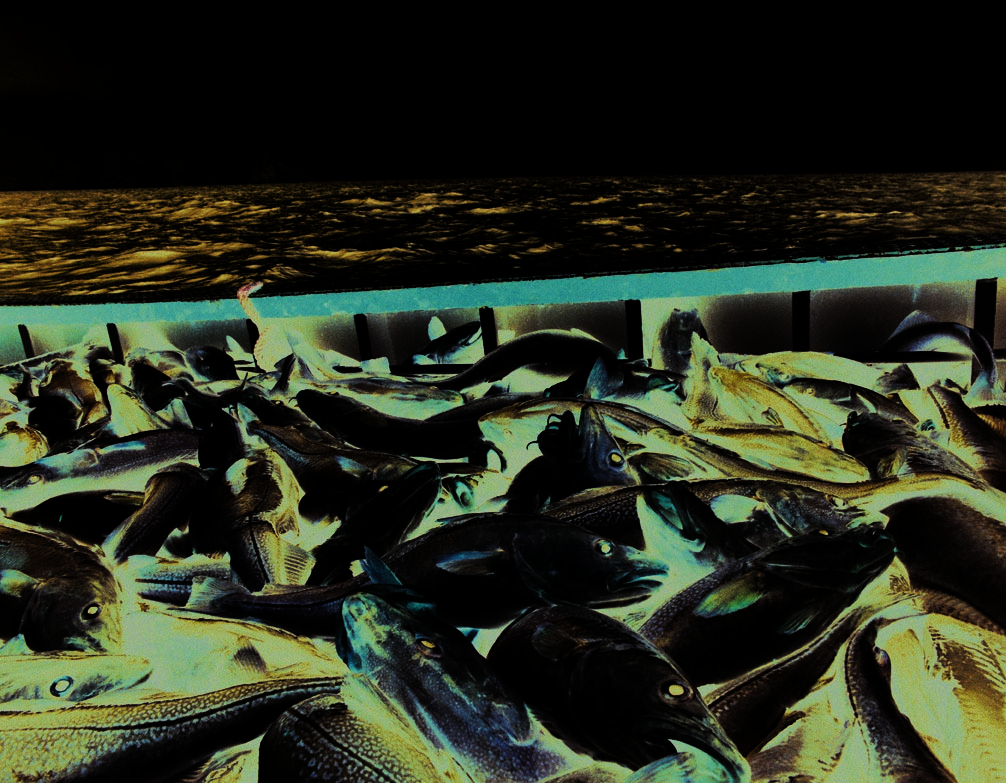

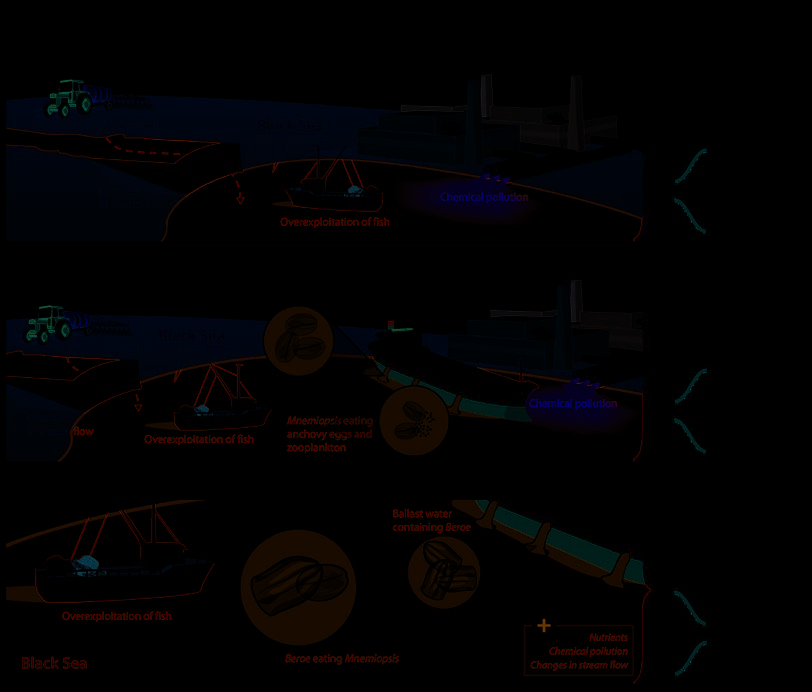

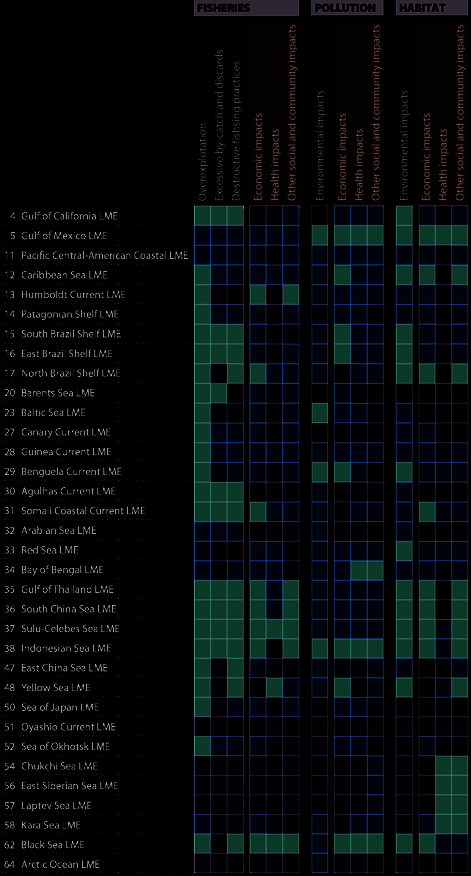

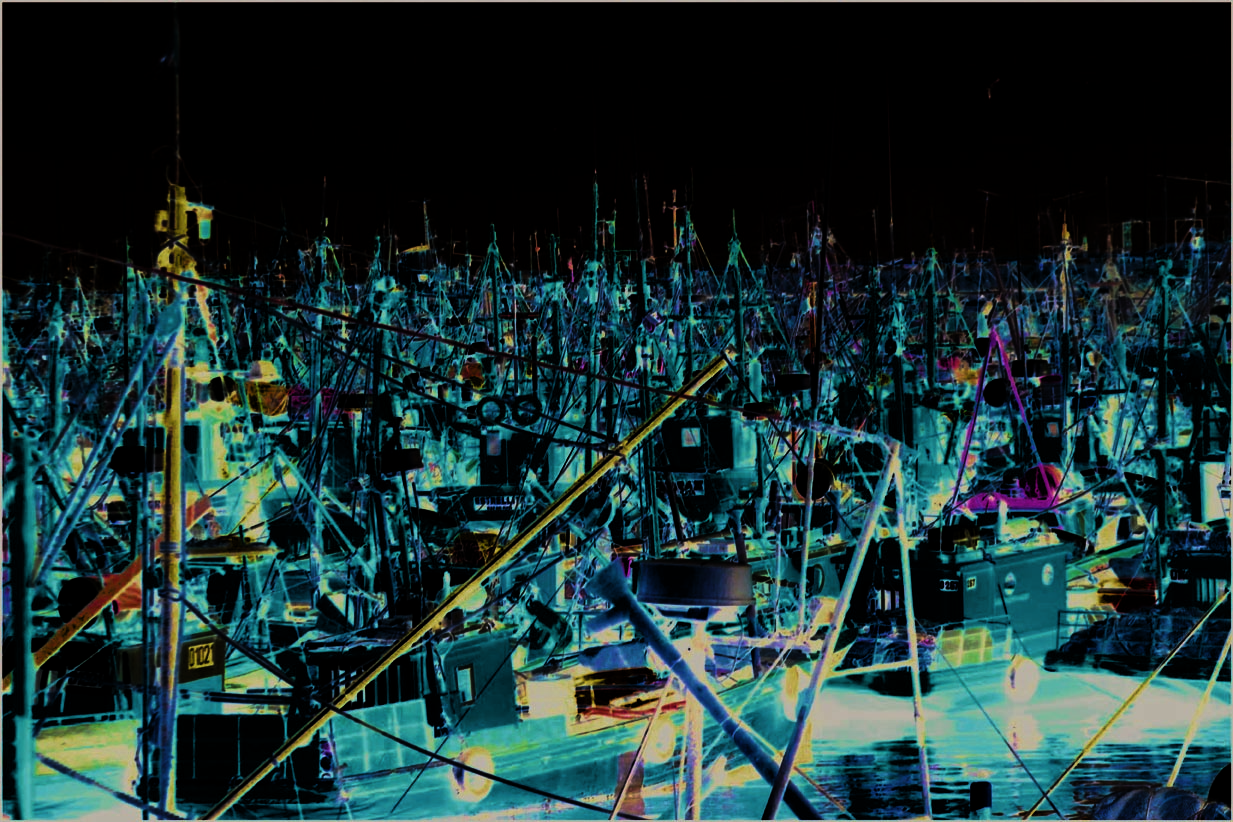

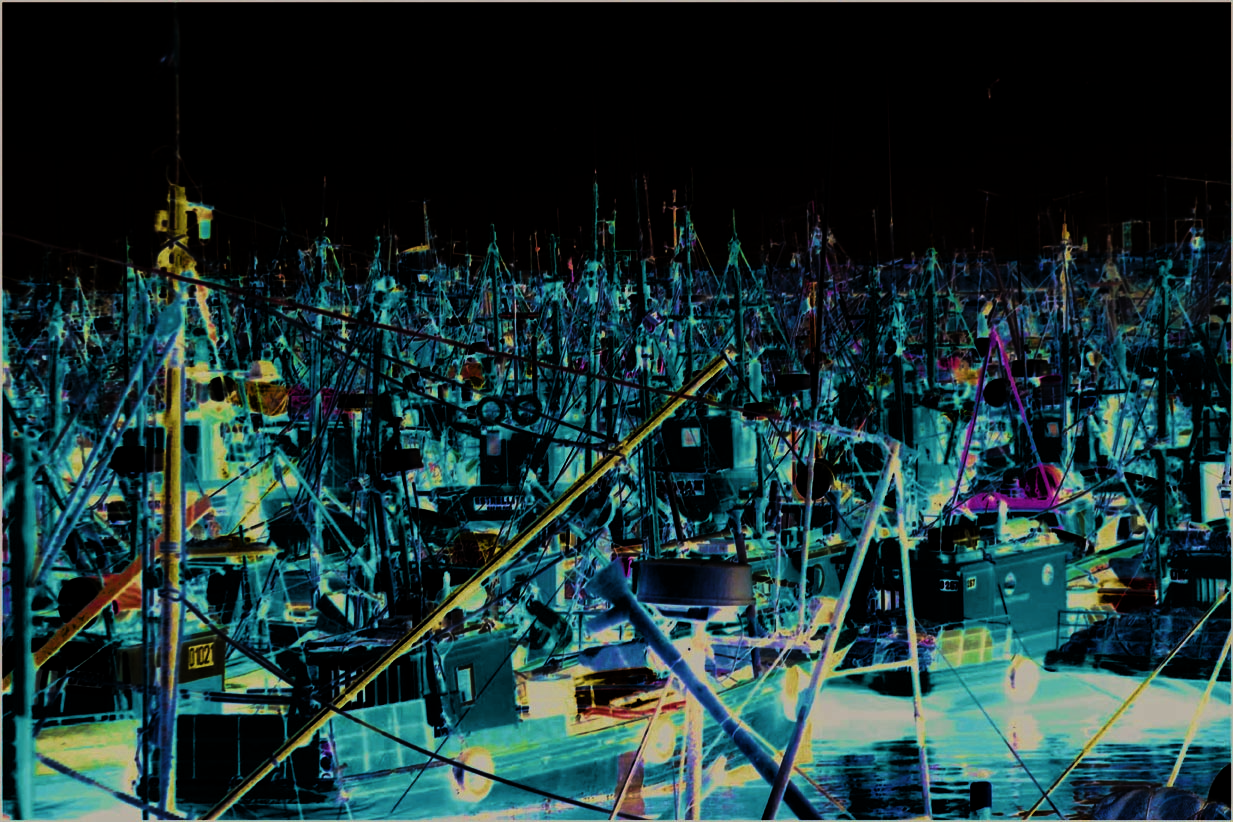

OVERFISHING AND OTHER THREATS TO AQUATIC LIVING RESOURCES . . . . 54

Environmental and socio-economic impacts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Root causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Policy relevant conclusions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

HABITAT AND COMMUNITY MODIFICATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Environmental and socio-economic impacts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

Root causes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Policy relevant conclusions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

CONCLUSIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

ACRONYMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

ANNEXES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

Annex I: Global International Waters As es ment Origin, objectives, workplan, teams and products . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Annex II: GIWA methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

Annex III: GIWA's key: Causal chain and policy options analysis in a theoretical perspective . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

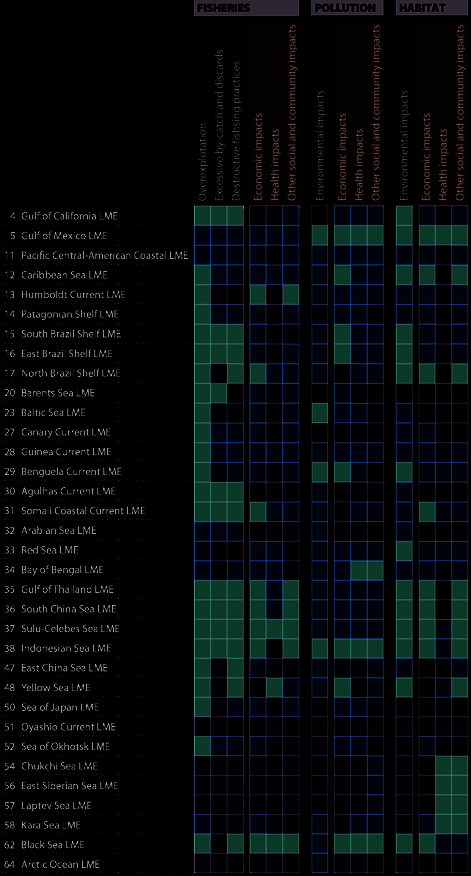

Annex IV: Matrix of GIWA Concerns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

PREFACE

5

PREFACE

5

Preface

Clean water and the many products and services of aquatic

Sound scientific assessments of the current state of all

ecosystems are necessities for human welfare. Water connects

freshwater and coastal marine resources and their aquatic

human societies and ecological systems by providing food

ecosystems;

and energy. e hydrological cycle maintains the health and

Informed dialogue between governments, stakeholders

stimulates the productivity and diversity of all ecosystems.

and experts, based on the assessments;

Wherever rivers, lakes and aquifers, as well as coastal

Technological support and capacity enhancement; and

current systems and marine fish stocks, are shared by two or

Adequate financing for projects and programmes related

more nations, these transboundary resources are interlinked

to water resources and aquatic ecosystems.

by a complex web of environmental, political, economic and

security interdependencies. roughout history, while water

In recognition of these needs, UNEP has implemented the

has general y been shared peaceful y, competition for scarce

Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) project,

water resources can invoke conflict between nations sharing

funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and by

international waters. Today, global trade, migration and tour-

national donors, in particular Nordic countries. GIWA is a

ism, as well as global climate change, have created worldwide holistic and global y comparable assessment of the world's

dimensions to many water related issues.

transboundary waters, based on the recognition that inextri-

Over the past 20 years, the international community

cable links exist between the freshwater and coastal marine

has increasingly recognised and asserted the urgent need for

environment. GIWA integrates environmental and socio-

concerted actions to reverse the negative societal trends that

economic information to determine the impacts of a broad

adversely affect the world's aquatic systems and to achieve

range of influences on the world's aquatic environment. A

sustainability in the use of water resources.

global perspective of the world's transboundary waters was

Short-term commercial interests are often prioritised

achieved by conducting regional assessments in many of the

over long-term sustainable development. is is due to the

major international drainage basins and marine shelf eco-

false assumption that environmental protection and sus-

systems. e project focused on developing regions, regions

tainability can only be achieved at the expense of economic

with economies in transition and smal island states eligible

development and social wel -being. On the contrary, by in-

for funding by the GEF. GIWA identifies the priority concerns

vesting in environmental improvements significant economic

of each region, determines their societal root causes and, in

returns can be achieved through, for example, increased

most regions, considers options to resolve or mitigate these

ecosystem and resource productivity, improvements in public

causes.

health and poverty al eviation. Sustainable development is

In addition to GIWA regional assessment reports, the

only possible by enhancing environmental management.

project developed a new assessment methodology and ad-

Achieving sustainability in international waters re-

opted a bottom-up approach involving multidisciplinary

quires the development and implementation of practical

regional teams. About 1 500 experts from around the world

policies within an ecosystem-based management framework,

conducted the assessments in col aboration with the GIWA

including the fol owing components:

Core team, hosted by the University of Kalmar, Sweden. e

Political and societal commitments to tackle water-related

GIWA approach can serve as a platform for further assess-

chal enges in a concerted and cooperative manner;

ments and for the surveil ance of aquatic systems.

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

6

is GIWA Final Report provides a global synthesis of the methodology and its theoretical background. It also acknowl-

GIWA regional assessments. e multitude of aquatic trans-

edges the regional teams, focal points and core team who have

boundary environmental problems are discussed under the

contributed considerable effort towards this global assessment.

concerns of freshwater shortage, pol ution, overfishing and

Policy makers at al levels of government, global and re-

habitat modification. e report summarises the current and

gional non-governmental organisations, and other stakeholders

predicts the future state of transboundary water resources and

involved in the use, development and management of trans-

associated aquatic ecosystems, the societal root causes and

boundary water basins and their aquatic resources wil find the

driving forces that engender adverse environmental pressures,

results of this global synthesis invaluable.

and the causal relationships that underpin the deterioration of

It is my hope that "Chal enges to International Waters

aquatic environments and their resources. e report identifies

Regional Assessments in a Global Perspective" wil assist in

gaps in knowledge and presents conclusions relevant to the sus-

the development of a roadmap to environmental sustainability

tainable management of transboundary waters. is final re-

and wil inspire actions necessary to overcome the global chal-

port of the GIWA project, includes annexes describing the GIWA

lenges to aquatic resources and ecosystems.

Klaus Toepfer

United Nations Under-Secretary General and

Executive Director, United Nations Environment Programme

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

7

Executive summary

e Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) project

Pol ution

is a holistic and global y comparable assessment of trans-

Transboundary pol ution has a moderate or severe impact in

boundary aquatic resources in the majority of the world's

more GIWA regions than any other concern, and also has by

international river basins and their adjacent seas, particularly

far the gravest impact on human health. Pol ution is mainly

in developing regions. A bottom-up and multidisciplinary

concentrated in inland and nearshore systems. e most criti-

approach was adopted that involved nearly 1 500 natural and

cal transboundary pol ution issue is suspended solids, causing

social scientists from around the world. e GIWA project

the greatest impact in Latin America, Southeast Asia and

provides strategic guidance to the Global Environment Facil-

Sub-Saharan Africa. Large-scale land-use changes, including

ity (GEF) by identifying priorities for remedial and mitigatory

infrastructure development, deforestation and agriculture,

actions in international waters.

have increased the sediment load of international waters.

e present Final Report presents the major results and

Eutrophication has its most severe transboundary im-

findings of the GIWA regional assessments.

pacts in Europe & Central Asia and Northeast Asia. Ag-

On a global scale, GIWA has confirmed that pressures

ricultural run-off was identified as the primary cause, but

from human activities have weakened the ability of aquatic

the tremendous growth of aquaculture in several East Asian

ecosystems to perform essential functions, which is compro-

regions has also become a factor. Oxygen-depleted zones, an

mising human wel -being and sustainable development. e

extreme result of eutrophication, are now present not only in

complex interactions between mankind and aquatic resources enclosed seas, such as the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea, but

were studied within four specific major concerns: freshwa-

also in large coastal areas which have international y impor-

ter shortage, pol ution, overfishing and habitat modification.

tant fisheries. Global y, harmful algal blooms are consider-

Global change is considered as a fifth concern which over-

ably more widespread and frequent than they were a decade

arches the other four. It is clear that the five GIWA trans-

ago, a situation that is expected to further deteriorate by 2020

boundary concerns are serious worldwide problems that are

due to the increased application of agricultural fertilizers, es-

expected to increase in severity by 2020.

pecial y in Asia and Africa.

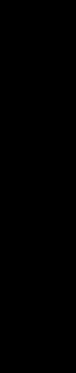

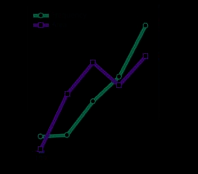

TABLE 1. TOP PRIORITY FOR THE GIWA CONCERNS BY MEGA REGION

North Africa

Australia &

Mega region

Arctic Rim

Europe &

Central

South

Sub-Saharan

Northeast

Southeast

Central Asia

America

America

Africa

& Middle

Pacific

East

Asia

Asia

Islands

Number of regions and

sub-systems assessed

Freshwater shortage

Pol ution

Overfishing and other threats to

aquatic living resources

Habitat and community

modification

Global change

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

9

Microbial pol ution is of particular concern in the

Salinisation was revealed by the regional assessments

freshwater ecosystems of tropical developing countries, but

to be more widespread and severe than is general y perceived.

is also widespread in Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) with

Reduced stream flow, inappropriate irrigation practices and

densely populated coasts. Microbial pol ution is projected to

overabstraction of groundwater have increased the salinity

increase due to population growth and urbanisation outpac-

of freshwater throughout the world. As a result, agricultural

ing the provision of sewage treatment facilities.

land is becoming too saline to support important crops, and

Chemical pol ution is also an issue of global impor-

salinisation has made many aquifers unsuitable as a source of

tance, inflicting moderate to severe impacts in more than half water for drinking and certain economic purposes.

of the regions assessed.

In arid and semi-arid areas, water shortages are pre-

Overal , pol ution is slight to moderate in most of the

dicted to be the most significant constraint for socio-eco-

LMEs, with severe pol ution limited to localised hotspots

nomic development. Global climate change will only exacer-

usual y found in close proximity to point sources of pol-

bate this problem. e most frequent socio-economic impacts

lution, such as sewage and industrial effluent outfal s and

resulting from freshwater shortages are the displacement of

river mouths, as well as in areas with limited water circula-

people, declines in fisheries production and reduced supply of

tion, such as semi-enclosed bays. Sea-based pol ution is most

potable water.

prevalent in LMEs with a high concentration of oil and gas

e progress being made to meet the Mil ennium De-

industries, and shipping activities.

velopment Goal (MDG) of halving the proportion of people

without access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation by

Freshwater shortage

2015 is a critical freshwater indicator. With 83 of the world's

e overabstraction of water resources is resulting in the dry-

population having access to safe water, the international

ing up of rivers, lakes and aquifers, leading to water shortages community, overal , is on track to meet the drinking water

in many GIWA regions. For Sub-Saharan Africa, it is un-

goal, with East Asia making the greatest progress. e MDG

doubtedly the top priority.

sanitation target is less likely to be achieved, with Sub-Saha-

In arid regions, in particular, water diversions lead to

ran Africa and South Asia making the least progress.

significant reductions in crucial low flow periods. e regula-

tion of stream flow by reservoirs changes natural water re-

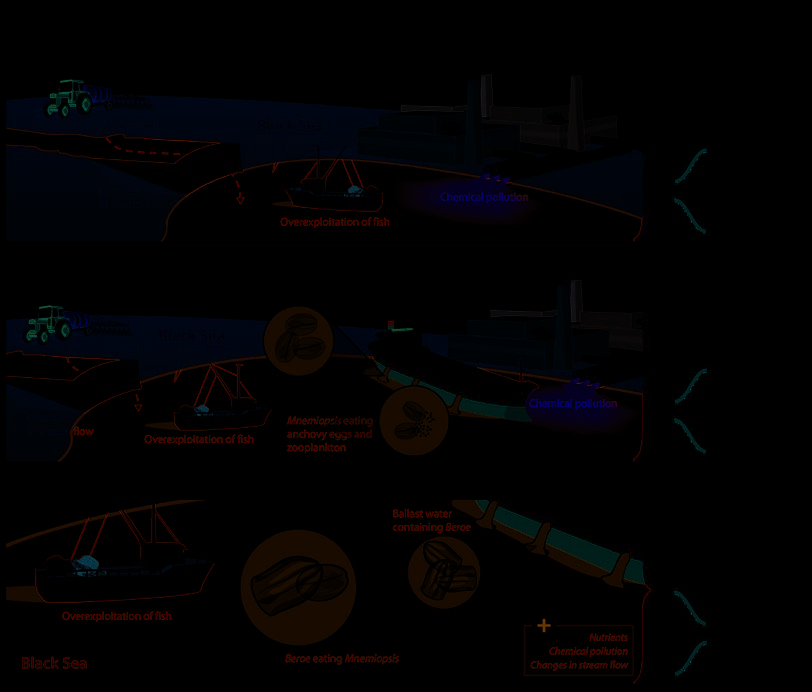

Overfishing and other threats to aquatic living resources

gimes. In many GIWA regions these changes adversely affect

Overexploitation of living resources was assessed as severe in

the productivity of downstream wetland ecosystems and sub-

more GIWA regions than any other GIWA issue. On a trans-

sequently the provision of their goods and services. e re-

boundary scale, large commercial fishing fleets are the major

duction in water inflow to enclosed water bodies can dramat-

contributors to the problem, exploiting specific transbound-

ical y alter their ecosystems. For example, in the Aral Sea/24, ary straddling and migratory stocks. However, the majority

water abstraction has reduced the volume of the sea by 60.

of fisheries in LMEs assessed by GIWA, especial y in the trop-

e overexploitation of water resources and changes in

ics, are artisanal. ey mostly operate on a geographical y re-

river basin hydrodynamics are largely attributed to the agri-

stricted scale, overexploiting many easily accessible nearshore

cultural sector, principal y as a result of water impoundment

species. A common environmental impact from overfishing

by dams and groundwater abstraction for irrigation, defores-

is `fishing down the food web', whereby fishers exhaust large

tation and drainage of wetlands to expand agricultural areas

predator populations, distorting the food web and forcing

and inappropriate agricultural land-use practices. About 70

fishers to target smal er, less valuable species.

of all abstracted water is utilised by irrigated agriculture, and

e environmental impacts of destructive fishing prac-

since many developing countries expect agriculture to be the

tices, including blast and poison fishing as well as bottom

main sector driving economic growth, water scarcity is likely

trawling in sensitive areas, are severe in most parts of the

to become an even greater problem in the future. Regions ex-

world. e issue of excessive by-catch and discards is most

periencing freshwater scarcity often also face severe pol ution, critical in Southeast Asia and South America. Discards rep-

further intensifying water stress.

resent an extraordinary waste of protein resources, with up to

90 of catches taken by shrimp trawlers thrown overboard.

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

9

With more than 200 mil ion people relying on fisher-

invasive species are the other major modifiers of freshwa-

ies for their livelihood and over 1 bil ion people depending on ter habitats. Alien species are known to have impacted the

fisheries for their protein supply, the world cannot achieve the structure of both marine and freshwater communities in

MDG of hunger eradication without improving fisheries man-

almost half of the GIWA regions, but many more remain un-

agement. Inadequate fisheries statistics hamper reliable stock

detected.

assessments and prevent effective fisheries management, par-

In Southeast Asia, coral reefs have been seriously

ticularly in developing regions. e socio-economic impacts

degraded by destructive fishing practices and coastal land

of fisheries mismanagement are dramatic. e overexploi-

reclamation. Mangrove forests are threatened by increased

tation of artisanal fisheries has the most detrimental social

demand for timber, coastal development and aquaculture in

impacts, as the communities that depend on these fisheries

Central America (the Caribbean), South America, Southeast

frequently have no alternative livelihoods, and malnutrition

Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. e rate of mangrove destruc-

often fol ows.

tion exceeds even that of tropical rainforests.

Aquaculture, which has been expanding rapidly for

Modification of habitats is particularly severe in tropi-

more than a decade, will supply an ever-increasing share of

cal LMEs, especial y in Central America, East Africa and

the global fish market. e question remains whether aqua-

Southeast Asia. Direct conversion of habitats for urban and

culture will be undertaken in a sustainable manner. e GIWA industrial development, mariculture, dredging, unsustain-

assessments from Southeast Asia indicate otherwise; hun-

able harvesting, poor land use practices in adjacent drainage

dreds of thousands of hectares of mangrove forest have been

basins, and pol ution are among the major causes of coastal

converted to fishponds since 1990.

and marine habitat modification. Transboundary effects are

Overexploitation of fish is general y expected to inten-

not uncommon, particularly if the habitats are nursery and

sify as a result of human population growth and an increasing spawning grounds for commercial y important migratory

demand for seafood, coupled with a continued lack of imple-

fishes, marine mammals and birds.

mentation and enforcement of regulations. On the other

Focusing on the critical tropical habitat of coral reefs,

hand, the situation in some regions studied by GIWA, par-

the GIWA regional assessments found degradation in all the

ticularly in Northeast Asia and Central America, is expected

tropical LMEs. Climate change, particularly increasing sea

to improve by 2020 due to the development and adoption of

surface temperatures causing coral bleaching, has emerged as

more sustainable fisheries practices.

potential y the greatest single threat to coral reefs.

Habitat and community modification was most fre-

Habitat and community modification

quently identified as the priority concern in Northeast Asia

e world's aquatic habitats have been extensively modified,

and South America. Socio-economic impacts included loss

particularly on land, with a consequential reduction in bio-

of fisheries and tourism revenues, greater unemployment,

diversity and an alteration of community structures in many

and the costs of mitigation and treatment actions, e.g. water

regions throughout the world. Hydropower, drinking water,

treatment and control of invasive species.

irrigation and flood mitigation are the major benefits of dams

and other structures that modify stream flow. is water in-

Linkages between the GIWA concerns

frastructure, however, is the single largest driver of habitat

including global change

modification in the world's rivers and a major factor affecting e GIWA regional reports frequently note the negative syner-

lake habitats. For example, in the Euphrates and Tigris River gies between the concerns, including global change. Consid-

Basin/50 more than 50 of the Mesopotamian wetlands have

ering the close links between many of the GIWA issues, habi-

dried out as a result of upstream water impoundment. e

tat and community modification could often be considered a

damming of rivers can also decrease sediment transport to

`downstream' consequence of the impacts of the other GIWA

estuaries, leading to additional coastal erosion and reduced

concerns. Frequently, freshwater habitats are radical y altered

productivity in marine ecosystems.

by changes in stream flow and nutrient transport resulting

Land-use change (mainly the conversion of forests

from the construction of dams and other structures. In ma-

and wetlands to agricultural land) and the introduction of

rine areas, overfishing has changed food webs and destructive

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

10

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

fishing has destroyed coastal habitats of high productivity

bination with inadequate water and wastewater infrastruc-

and biodiversity. Pol ution, mainly from agricultural run-off,

ture, often leads to water shortages. From a consumption

industrial effluents and domestic wastes, impacts both fresh-

perspective, rising income levels are expected to increase fish

water and marine systems.

consumption at nearly twice the rate of population growth in

Linkages are present in most regions and aquatic sys-

Asia.

tems. In Lake Victoria the introduction of Nile perch (Lates

niloticus), in combination with eutrophication and unsustain-

Agricultural development and economic growth

able fishing, has led to the extinction of several hundred spe-

GIWA regional teams identified expansion in the agricultural

cies of cichlid fish, the largest recorded vertebrate extinction.

sector, and in particular irrigation, as the most significant

On a broader scale, suspended solids, eutrophication, over-

cause of the transboundary concerns of freshwater shortage,

exploitation and destructive fishing practices are degrading

pol ution, overfishing and habitat modification. e environ-

seagrasses and coral habitats in tropical marine regions. e

mental impacts associated with agriculture include eutrophi-

socio-economic impacts from these negative synergies often

cation stimulated by fertilizer run-off, suspended solids from

spiral into increasing local poverty, declining health stan-

increased erosion fol owing forest colonisation, and stream

dards and growing conflict.

flow modification to provide water for irrigation. Global y,

Recent mass coral bleaching events related to the El

there has been an increased demand for agricultural products

Niño Southern Oscil ation are the most dramatic example

and a trend towards more water-intensive food, such as meat

of climate change affecting a specific type of ecosystem on

rather than vegetables, and fruits rather than cereals. Many

a global scale. In future climate change scenarios, highly

developing countries also see the development of agriculture

productive fisheries associated with climate mode-driven

as the main engine for economic growth.

upwel ing are at serious risk. At the regional level, freshwa-

With nearly one-third of agricultural water used to

ter availability wil be affected by climate-induced changes

produce export crops, trade is a critical factor. Several GIWA

to precipitation patterns, increasing in some regions, such as regional reports from Sub-Saharan Africa note that trade

Southeast Asia, and decreasing in others, such as the sub-

has increased the production of water-demanding crops,

tropics. Higher temperatures wil result in greater evapora-

putting additional stress on water resources and the environ-

tion rates, thus threatening freshwater supplies and trig-

ment.

gering additional droughts in arid and semi-arid regions.

It is clear that irrigation wil continue to expand, under-

Furthermore, climate change is expected to intensify the

scoring the need to increase efficiencies in water use and de-

effects of pol ution, including an increase in the size and

velop new approaches to demand management. e concept of

duration of oxygen-depleted zones. Rising sea levels are an-

virtual water may be an important tool for understanding and

ticipated to increase saline intrusion in coastal aquifers and

mitigating the impact of trade on water resources.

cause saltwater to reach further upstream in rivers. ese

Water management policies have traditional y fo-

expected changes are driven by major alterations in the

cused on water supply and ignored demand management.

global hydrological cycle, and may have severe impacts on

e freshwater shortages experienced in rapidly developing

human wel -being. While few GIWA regional teams identi-

regions, such as Southeast Asia, il ustrate the need to prevent

fied global change as their top priority at present, the major-

water demand from growing in lockstep with economic de-

ity predicted that this concern would become more serious

velopment.

by 2020.

Lack of knowledge and public awarenes

Root causes

Detailed knowledge of resource stocks and yields, as well as

Population growth

demand patterns, is often deficient, particularly in develop-

Population growth is an important root cause of all water-

ing countries. Aquifers represent the largest information

related concerns. e world's growing population is increas-

gap, which is an increasingly significant hindrance for effec-

ing water stress. In Africa, for example, even though water

tive water management given the growing dependence on

consumption per capita is low, population growth, in com-

groundwater.

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

10

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

e dynamics of fish populations, especial y in devel-

these fishers frequently adopt destructive fishing practices,

oping countries, are frequently unknown. In the industrial

putting further pressure on beleaguered fisheries, and ul-

fisheries sector, inaccurate information, in combination with

timately reducing household income, nutrition and health

political and societal pressure to maintain fishing effort, has

levels.

led to overexploitation and the col apse of many fisheries.

Public awareness of environmental problems is rather

Policy failures

rudimentary at all levels of society in most developing regions Policy failures commonly result from the inability of institu-

as well as in many developed countries. Education and con-

tions to perform three key functions: (i) recognise signals

sumer information are required everywhere, from rural to

of a problem and agree on its nature; (i ) reach agreements

urban communities and from primary schools to universities.

that balance the interests of stakeholders both within and in

e GIWA regional teams also highlighted the need for far

other countries; and (i i) implement and enforce these agree-

broader multi-disciplinary, institutional and public/private

ments.

sector communication in the management of international

e first function is hindered by knowledge deficiencies

waters. e strengthening of professional capacity is impor-

regarding aquatic resources and a lack of public awareness of

tant, not only for research and teaching but also for policy

their impact on aquatic ecosystems. Common indicators are

making and management.

needed to monitor the state of ecosystems and their interac-

tions with human activities. International cooperation is con-

Market failures

strained in many regions by the fact that politicians and other

roughout the world, most production inputs are under-

leaders do not even recognise aquatic systems and resources

priced compared with their full social and environmental

as being transboundary.

costs. An egregious example is blast fishing, where the in-

Even when reliable information is available, environ-

vestment of one dol ar for dynamite can generate an imme-

mental considerations or broad stakeholder involvement are

diate 200-fold return for the local fishermen, but leaves a

often disregarded in the decision-making process. Institu-

devastated reef that takes 50 years to recover. While devel-

tions responsible for specific sectors, such as fisheries, ag-

oped countries have made some progress in reducing input

riculture or transportation, general y dismiss concerns that

subsidies, both developed and developing countries still com-

transcend their limited sectoral goals.

monly offer large subsidies on, for example, electricity, fuel,

Within most parts of the world, regional initiatives

pesticides, fisheries and infrastructure. Political will to reduce aimed at improving environmental management have been

inappropriate subsidies often fails in the face of potential job

developed. ese include the ratification of a number of in-

losses, lobbying by industry, and corruption.

ternational environmental conventions and the adoption of

Historical y, water was regarded as an infinite and free

several non-binding frameworks. However, implementa-

resource; consequently, water is commonly underpriced in

tion and enforcement of agreements frequently fail due to:

many GIWA regions, particularly in the agricultural sector,

(i) weak human and financial resources; (i ) a lack of political

encouraging waste and discouraging infrastructure invest-

commitment; (i i) weak institutional frameworks; (iv) inad-

ment. Ecosystem goods and services are insufficiently valu-

equate information; (v) corruption; and, to a lesser extent, (vi)

ated or considered when formulating development strategies.

inappropriate regulations.

Many regional reports note that a key to improving manage-

Given the difficulty in reaching and implementing

ment is to stop focusing only on the direct economic benefits

agreements at the national level it is not surprising that ef-

of engineered structures, and to evaluate their long-term en-

forts to establish transboundary policies, let alone manage-

vironmental, economic and social benefits and costs.

ment, remains an elusive goal in most regions. Weak inter-

It is the very nature of common pool resources, such

national and regional commissions are testament to this fact,

as the fisheries, that it is difficult to exclude newcomers, who

but there are success stories in both developed and developing

have no knowledge of the resource they seek to exploit. A vi-

regions, notably in fishery regulations and in water manage-

cious spiral can begin, where increasing numbers of fishers

ment in several major river systems.

chase smal er fish populations. To boost their meagre catches,

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

12

Response options

need to be implemented gradual y, but these changes will

e United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-

vary widely on a regional rather than on a national scale. To

navigational Uses of International Watercourses provides

implement such policies it is necessary to raise both public

a framework for intergovernmental river basin agreements.

and political awareness of the importance of addressing water

Although there have been positive developments in recent

concerns and the associated socio-economic impacts. Such

decades, only one third of the world's transboundary basins

initiatives must be based on sound knowledge and multidis-

have established treaties, basin commissions or other forms

ciplinary efforts, like GIWA, where the natural and the social

of cooperative management frameworks. Even where inter-

sciences are united in a joint endeavour.

governmental agreements exist, they seldom address today's

In the marine environment, the fishing industry over-

chal enges to water management.

exploits the majority of living resources and degrades marine

Policy options cannot be confined to actions that target habitats, resulting in a loss of biodiversity and changes in

natural and physical processes but should consider the human community structure. Given the inability of past responses

dimensions of water use as wel . Policy measures must there-

to halt the degradation of marine ecosystems, the concept of

fore be formulated to address the local situation. At the same

ecosystem-based management is increasingly adopted for the

time, it remains important to develop broad themes for devis-

management of LMEs with support from the GEF. Ecosystem-

ing policies and basin-wide management for the sustainable

based management requires the implementation of a com-

use of transboundary rivers.

bination of measures, including precautionary catch regula-

First and foremost, it is necessary to reduce the impacts tions, the introduction of sustainable rather than destructive

of water scarcity and habitat degradation by developing inter-

fishing methods, the reduction of fishing effort and the re-

national governance frameworks for equitable water al oca-

form of subsidies. Marine parks and zones which temporarily

tion in accordance with the above-mentioned Convention.

close or restrict access to fishers and other marine activities

Disputes and conflicts over water use can only be resolved

can protect sensitive habitats.

through common strategies and commitments between up-

Many of the GIWA regional teams have recognised that

stream and downstream countries. An integrated approach

ecosystem-based management, including integrated coastal

linking water management to land management and eco-

zone management, is an effective policy response for halt-

nomic management is also needed.

ing or reversing the degradation of large marine and limnic

Improved policies and pricing, particularly for achiev-

ecosystems.

ing increased user efficiency and socio-economic benefits,

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

13

Acknowledgements

is publication would have been impossible without the hard work and unwavering ded-

ication of a large number of scientists and experts in the GIWA network. Over 1 500 ex-

perts around the world have contributed most of the data and analyses in the regional and

thematic assessments which were used as a basis for producing this final report of GIWA.

is publication has gone through a lengthy drafting period. UNEP would like to ac-

knowledge the fol owing persons who have contributed to the production of this report

(in alphabetical order):

Juan Carlos Belausteguigoitia

Sanna Mels

Kristin Bertilius

David Moffat

Pierre Blime

Joakim Palmqvist

Dag Daler

Elina Rautalahti-Miettinen

Matthew Fortnam

George Roman

Rasmus Göransson

Pinya Sarasas

Pertti Heinonen

David Souter

Gotthilf Hempel

Johannes Wolpert

Olof Lindén

Ul a Li Zweifel

Marianne Lindström

A special acknowledgement is also extended to reviewers for their constructive comments

and feedbacks (in alphabetical order):

David Aubrey

Mogens Dyhr-Nielsen

Sara Gräslund

Pertti Heinonen

Hans Olav Ibrekk

Lea Kauppi

Norman Lee

For a comprehensive list of individuals who have been involved in various aspects of the

GIWA project, see Annex I.

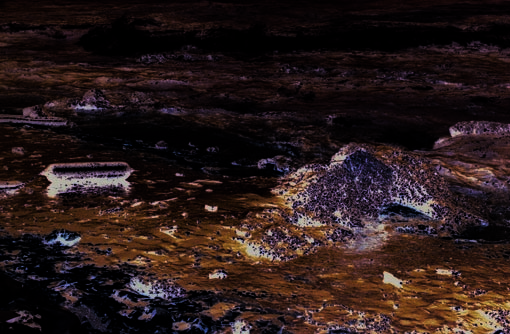

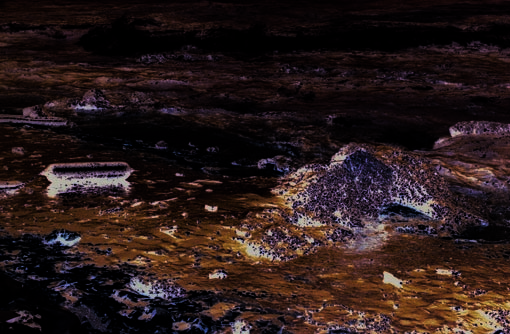

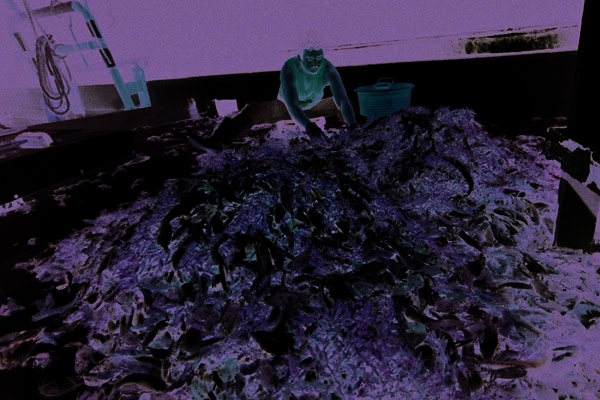

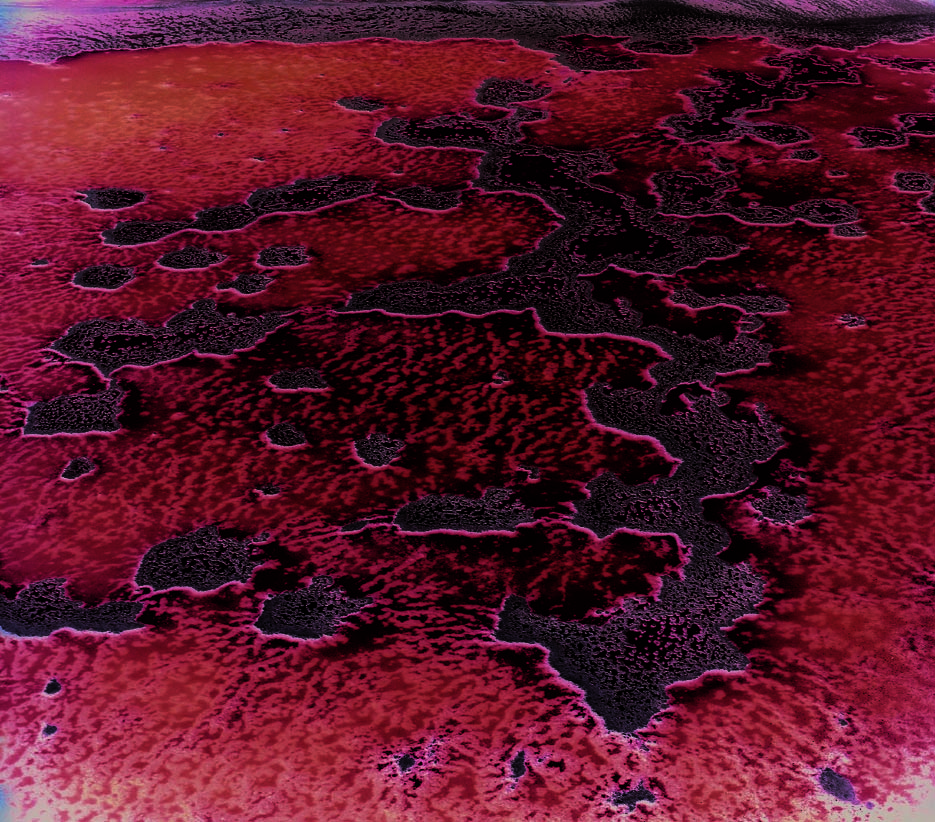

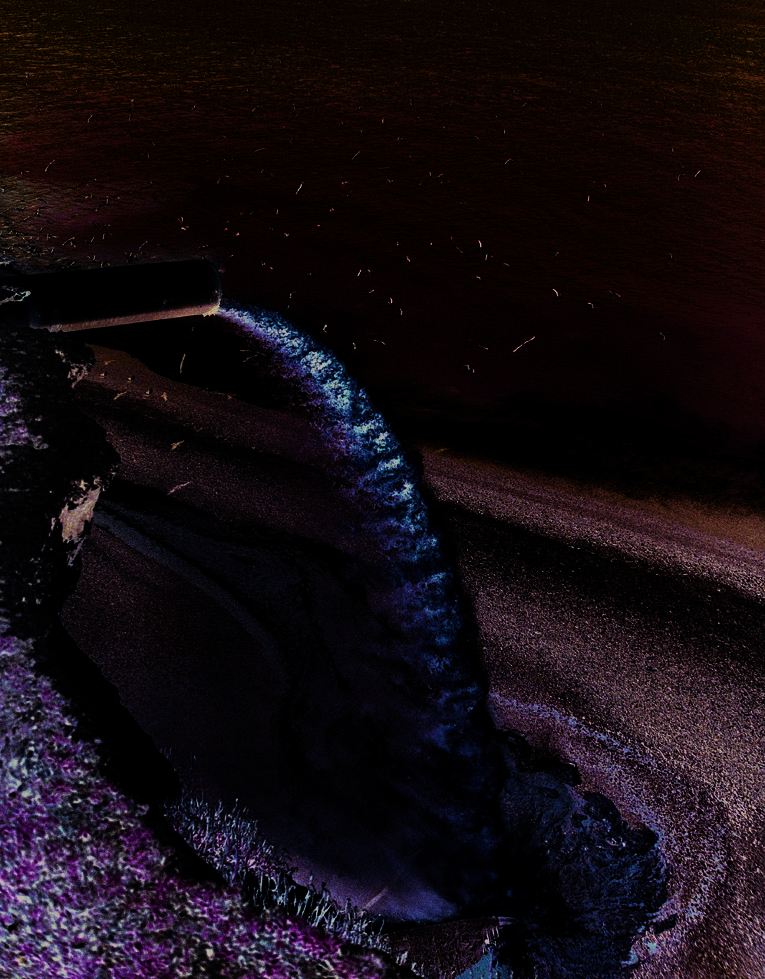

KIUNGA NATIONAL MARINE RESERVE, KENYA

INTRODUCTION

15

(PHOTO: G. HEMPEL)

INTRODUCTION

15

Introduction

Only a small proportion of global freshwater can be used by

effects are interlinked and can be traced back to a number of

humans for drinking, sanitation, agriculture and industry,

common root causes.

as well as by the inland fisheries and aquaculture. e living

e Global Environment Facility (GEF) has been estab-

resources exploited by marine fisheries and mariculture are

lished to inter alia "contribute primarily as a catalyst to the

predominantly restricted to the relatively narrow and shal-

implementation of a more comprehensive, ecosystem-based

low fringes of oceans. e various human activities increas-

approach to managing international waters and their drain-

ingly compete for limited aquatic resources. e growth of

age basins as a means to achieve global environmental ben-

human populations and their economies, urbanisation and

efits".

the globalisation of trade, in combination with global climate

e absence of a worldwide comprehensive and inte-

change, will further increase this pressure.

grated transboundary waters assessment has hampered the

Water and its resources are exploited at differing in-

efforts of the GEF to meet its objective and to identify priority

tensities and for various purposes in different parts of the

regions and issues for international support. us, the GEF

world. Consequently, the impact of aquatic concerns, includ-

commissioned UNEP to implement the Global International

ing freshwater shortage, pollution, habitat and community

Waters Assessment (GIWA) project in order to develop a stra-

modification, and overfishing, vary in severity and extent.

tegic framework that may be used by the GEF and its partners

ese concerns were traditional y assessed either on a na-

to identify priorities for remedial and mitigatory actions in

tional scale, individual y on a global scale, or for a specific

international waters. See Annex I-III for further information

water body.

on the GIWA project.

Many freshwater and coastal ecosystems are interna-

e GIWA project was executed by UNEP in partnership

tional; 263 river basins cross or delimit national borders, con-

with the Government of Sweden, through the Swedish Inter-

veying about 60 of the world's freshwater flow and draining national Development Cooperation (SIDA). e Government

more than half the Earth's land area. Most Large Marine

of Finland later became a partner to the project. In 1999,

Ecosystems (LMEs) and large groundwater aquifers are shared they established the GIWA Core team at Kalmar University,

by two or more countries. Downstream consequences of

Sweden.

human activities can occur in regions some distance from the

GIWA focused on transboundary water issues in devel-

source of the problem. In order to address these water issues,

oping regions. However, in order to provide a more global

they must be assessed from an international (or transbound-

coverage, comparable information was col ated from regions

ary) perspective.

containing developed countries that are not eligible for GEF

Over the past decade, the international community has

interventions.

increasingly acknowledged the need for a global approach to

GIWA adopted a bottom-up approach involving regional

assessing transboundary aquatic resources and has recog-

experts. ey evaluated the severity of transboundary eco-

nised the importance of water for sustainable development.

logical and societal impacts and their causes in international

While aquatic environmental concerns are global issues, they

waters on a regional scale. e root causes, including global

are usual y addressed on a regional scale, i.e. for each water

trends, policy, legislation, governance, institutional capacity

system. Within the region, a holistic approach to assessment

and knowledge, were analysed by the experts. Final y, policy

and management is required, as all aquatic concerns and their relevant conclusions were drawn from the assessments.

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

16

INTRODUCTION

17

e GIWA project provides strategic information that

4. Habitat and community modification

can assist in meeting the Mil ennium Development Goals

5. Global change

(MDGs), particularly for the eradication of hunger (Goal 1)

and increased access to safe drinking water (Goal 7).

Global change largely causes impacts by affecting the

four other concerns and many regional teams were unable to

Project design

assess it due to a lack of data. Consequently, global change is

e transboundary regional approach to assessing global

integrated into the discussions on the other concerns in this

problems constitutes the backbone of GIWA. e inland water

report.

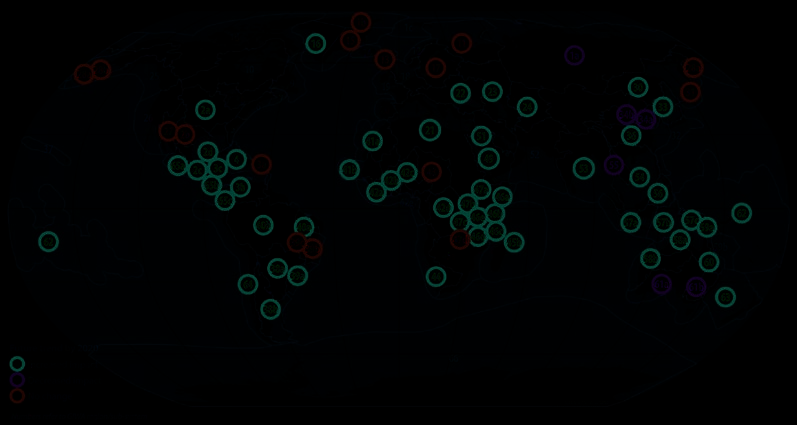

systems and shelf seas of the world were divided into 66

e GIWA methodology is comprised of four major steps

transboundary geographical regions, 41 of which are GEF-eli-

(for further information and discussion on the GIWA meth-

gible. Each region comprises one or more international river

odology see Annex II, and for its theoretical background,

basin and usual y an adjacent LME. A few regions are land-

Annex III):

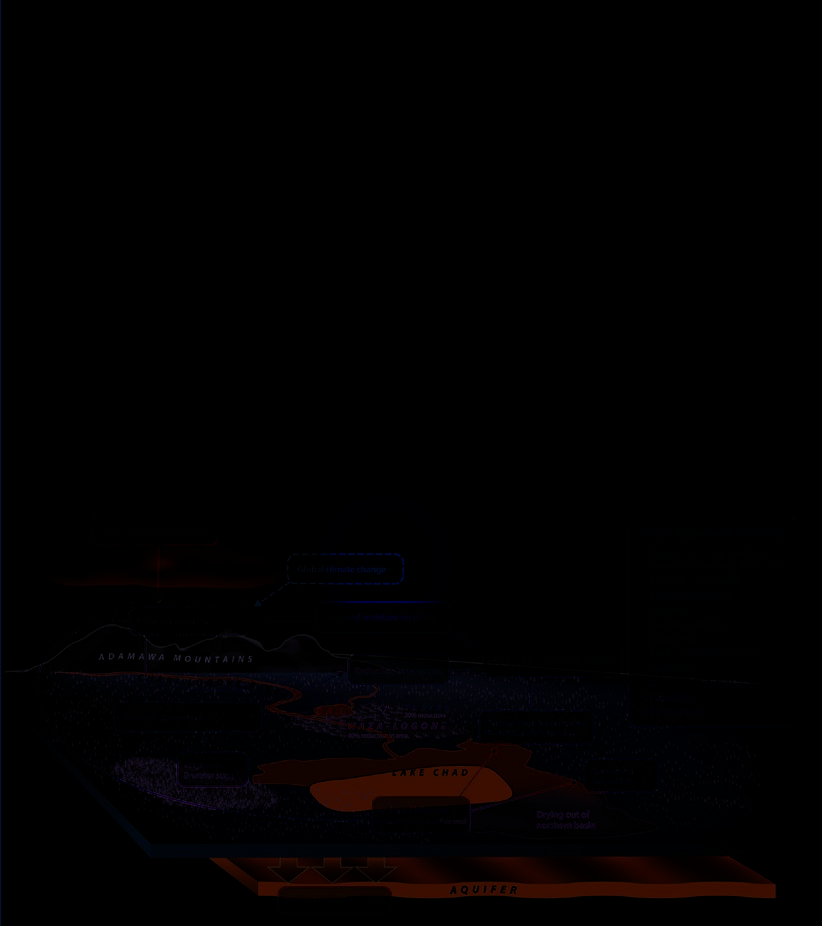

locked, such as Lake Chad/43. Several regions were divided

Scaling defines the geographic boundaries of the GIWA

into sub-systems, which were assessed individual y (see map

region, which are general y demarcated by a large drainage

on the inside of the front cover). e high seas were not as-

basin and its adjacent marine areas. e boundaries of the

sessed by GIWA.

marine parts of the GIWA regions often correspond with those

e assessments were conducted by 1 500 scientists and

of LMEs.

administrative and managerial experts, who were organised

Scoping assesses and scores the severity of present and

into regional teams led by a focal point from the region. e

predicted environmental and socio-economic impacts caused

multidisciplinary teams included representatives from each

by each of the GIWA concerns.

country in the region. e Core team was responsible for

Causal chain analysis traces the cause and effect path-

overall project management, methodology development, the

ways from the socio-economic and environmental impacts

coordination of the regional teams, and peer review and pub-

back to their root causes.

lication. e Core team, in cooperation with external experts,

Wherever possible, the causal chain analysis was fol-

also produced this GIWA Final Report.

lowed by policy option analysis which outlined potential

courses of action that aim to mitigate or resolve environmen-

The GIWA assessment methodology

tal and socio-economic problems in the region.

Global y comparable results were achieved by a common

e GIWA provides baseline information at the regional

and consistent methodology applied by all of the regional

level which will facilitate the preparation of Transbound-

teams. e GIWA methodology provides criteria for assess-

ary Diagnostic Analysis (TDAs) and Strategic Action Pro-

ing water-related environmental concerns, and for identifying grammes initiated by GEF. At the same time, many GIWA re-

their immediate and root causes and potential policy options

gional assessments have benefited from completed TDAs.

(see Annex II and III). Regional experts assessed and com-

pared the severity of impacts from a regional perspective. e The GIWA approach

methodology was not developed for inter-regional compari-

Although GIWA is not the only assessment of the world's

sons of environmental quantitative data, such as pol utant

aquatic systems and resources, it has taken an original ap-

concentrations or loss of mangroves. Instead, the GIWA deter-

proach that will benefit a wide range of stakeholders. e

mines regional priorities and al ows a relative comparison of

number and diversity of regional experts, and the peer review

multiple impacts.

process, has ensured transparency in the regional assess-

e numerous and complex transboundary water-re-

ments. GIWA uses a holistic and ecosystem-orientated ap-

lated environmental problems were grouped into five major

proach to assess the environmental and socio-economic im-

concerns:

pacts, and root causes behind environmental problems.

1. Freshwater shortage

Traditional y, global assessments adopt a top-down

2. Pol ution

approach; led by small teams of international experts with

3. Overfishing and other threats to aquatic living resources

relatively limited inputs from local stakeholders. GIWA has

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

16

INTRODUCTION

17

taken the opposite approach, with local experts leading each

The GIWA Final Report

regional assessment, thus building strong local ownership

is report provides a synoptic review of the most important

of the GIWA regional reports. By facilitating international

information from the regional reports. It is a technical rather

cooperation and fostering trust among scientists and policy

than a comprehensive scientific publication. Prime references

makers from neighbouring countries, GIWA has strengthened

can be found in the regional reports, which are referenced in

national assessment capacity and provided the basis for long-

this report by GIWA region (name fol owed by number, e.g.

term col aboration in developing regions.

Mekong River/55).

roughout the process of undertaking the regional as-

sessments and preparing the regional reports, the training of

e book:

many young scientists served to strengthen scientific capacity summarises the major transboundary concerns and their

in specific regions. GIWA not only assessed the available policy

impacts;

relevant information, but also identified key knowledge gaps

assesses the root causes of the impacts; and

that need to be addressed.

provides policy relevant conclusions.

In addition to their own knowledge, the regional ex-

perts drew, to varying extents, from complementary assess-

e GIWA scoring matrices in Annex IV present the scoring

ments and initiatives, including: the UN World Water De-

results of the five concerns for each region and sub-system.

velopment Report; the Mil ennium Ecosystem Assessment;

e severity of the GIWA concerns and issues are expressed

the Mil ennium Development Goals; the UN Commission on using the terms `severe', `moderate', `slight' and `no reported

Sustainable Development; Food and Agriculture Organiza-

impact', which are described in Annex II. `Environmental

tion assessments; and national studies. ere is considerable

impacts' represent the average weighted score for the environ-

overlap in membership of the various assessment groups and

mental issues associated with the concern. `Overall impacts'

in the data sources used.

refers to the concern's final score including environmental,

e GIWA methodology brought together natural and

socio-economic and the anticipated future impacts. e pre-

social scientists and resource managers, often for the first

dicted trends of the environmental impacts are represented by

time, to participate in the workshops, conduct the assessment arrows in the overall impacts column.

and compile the regional report.

For various reasons, some regional reports have not

Each GIWA regional assessment fol owed the same pro-

been published and were therefore unavailable during the

cess. Training courses for the regional teams ensured that

drafting of the Final Report. Many GEF non-eligible regions

they all possessed a common understanding of the GIWA

were not assessed, mainly in Europe and North America.

methodology.

Some areas of the Middle East and Southern Asia are also

e regional assessments are the primary outputs of

unrepresented. ose gaps may give a misleading impres-

the GIWA project. Fifty-five regional assessments have been

sion that there are no transboundary water problems in these

completed, forty of which include GEF-eligible countries. e

regions.

present status of the GIWA regional reports is presented on the

is synthesis of all concerns, their issues and impacts

map inside the front cover. e reports are also available on

provides a global perspective on their relative importance.

the GIWA website (www.giwa.net).

Readers are encouraged to consult the regional reports for

GIWA has been the largest global assessment of eco-

more information about the examples contained in this re-

system-wide water issues from a transboundary perspective,

port. e Annexes provide additional information on the

linking international river basins to their adjacent LMEs. It

GIWA project and methodology.

was designed to provide policy makers and managers with

the information they need to improve transboundary re-

sources management.

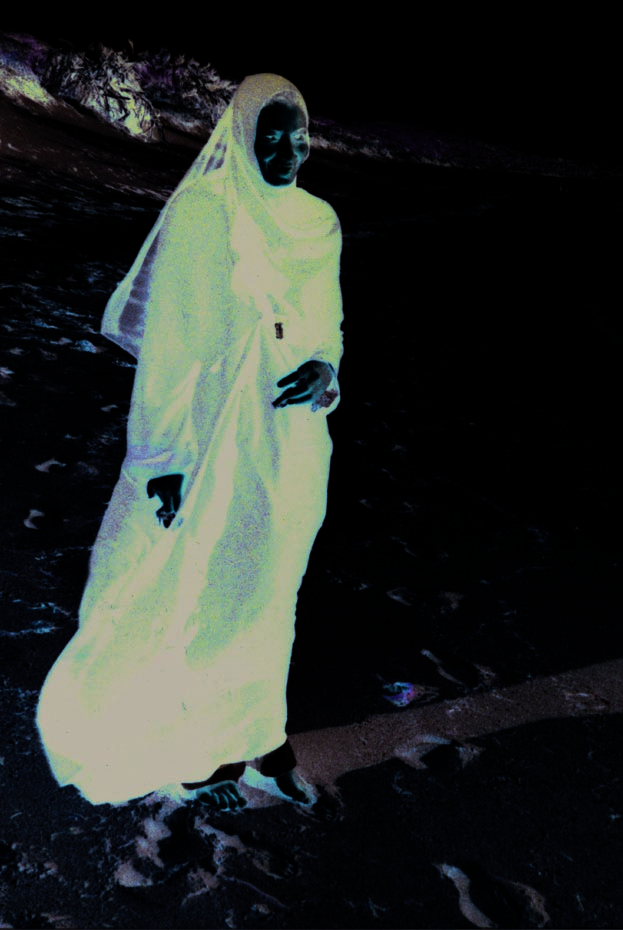

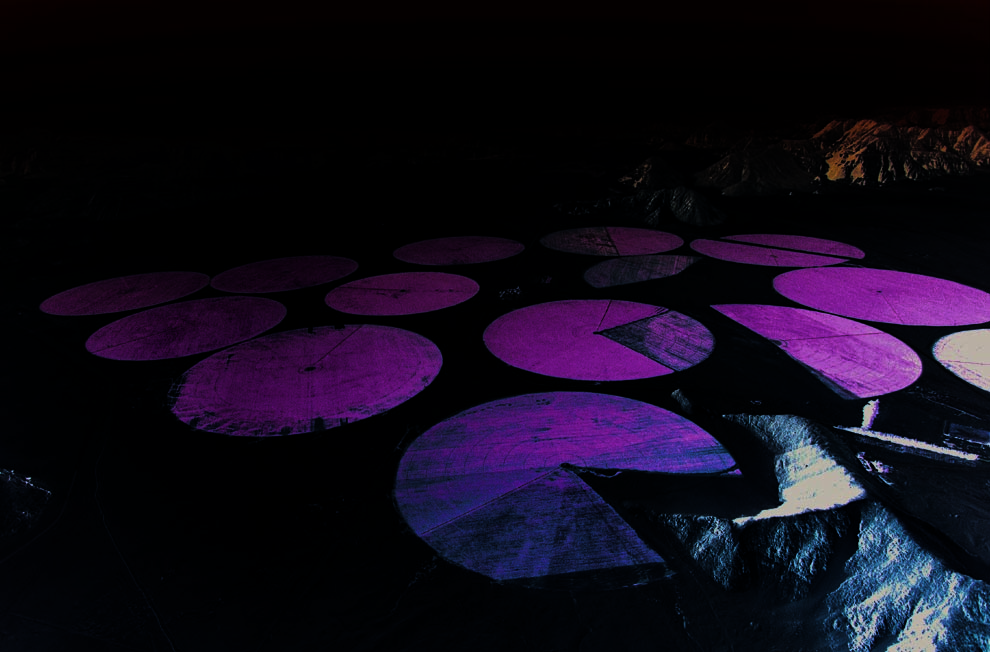

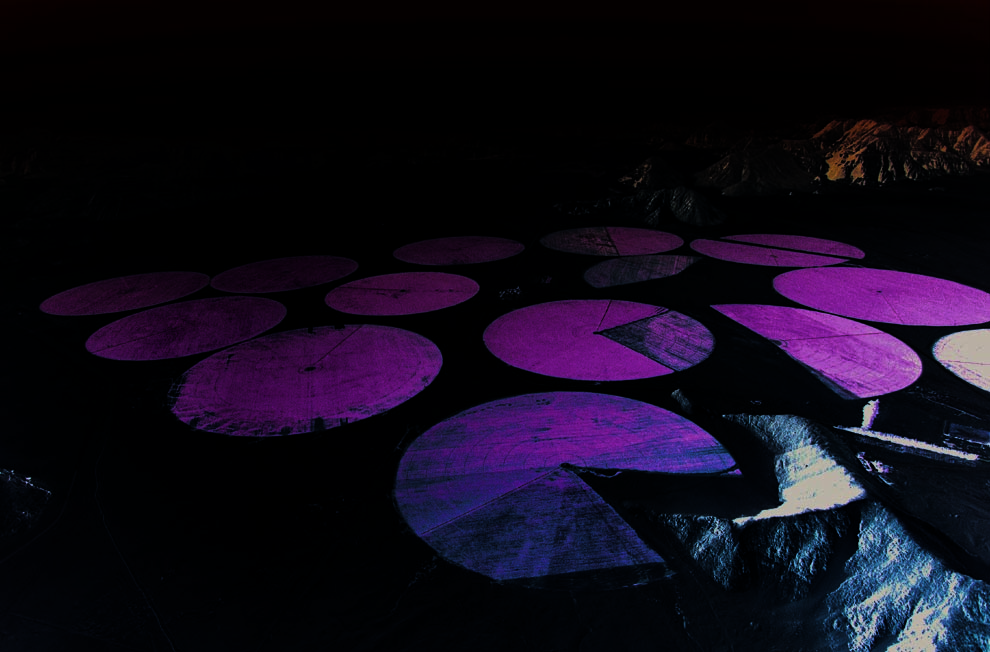

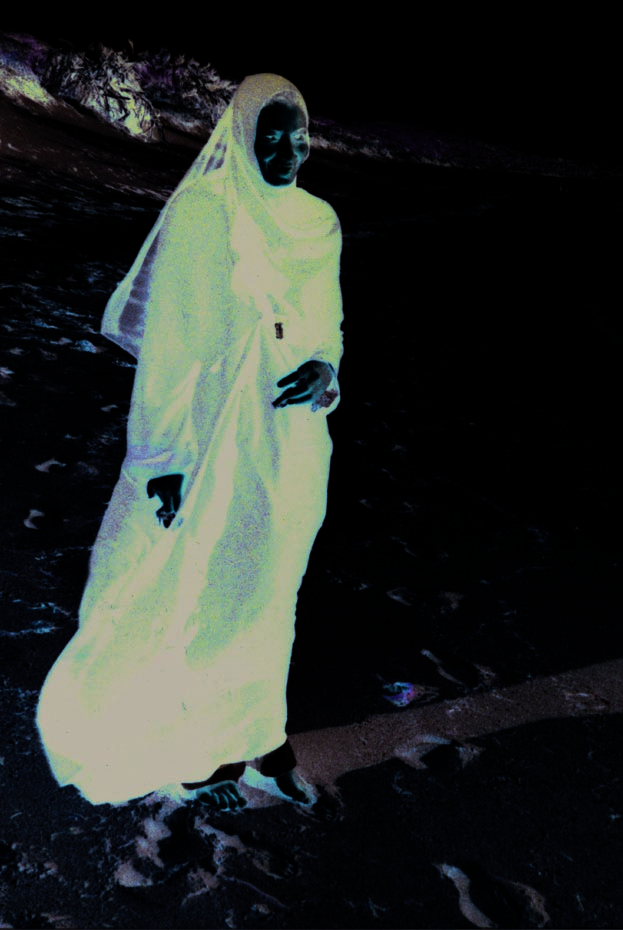

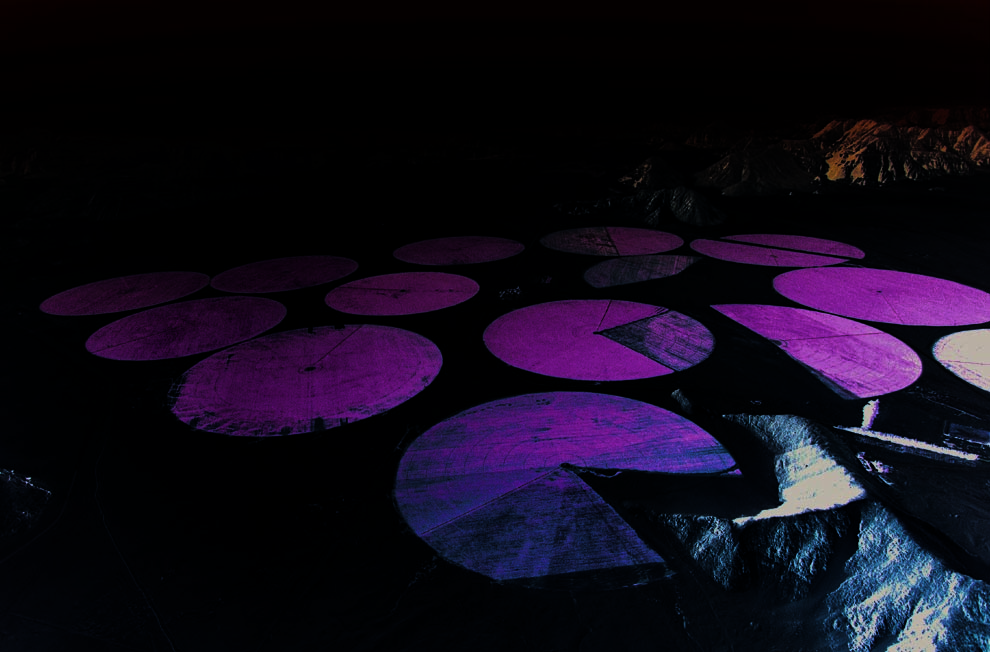

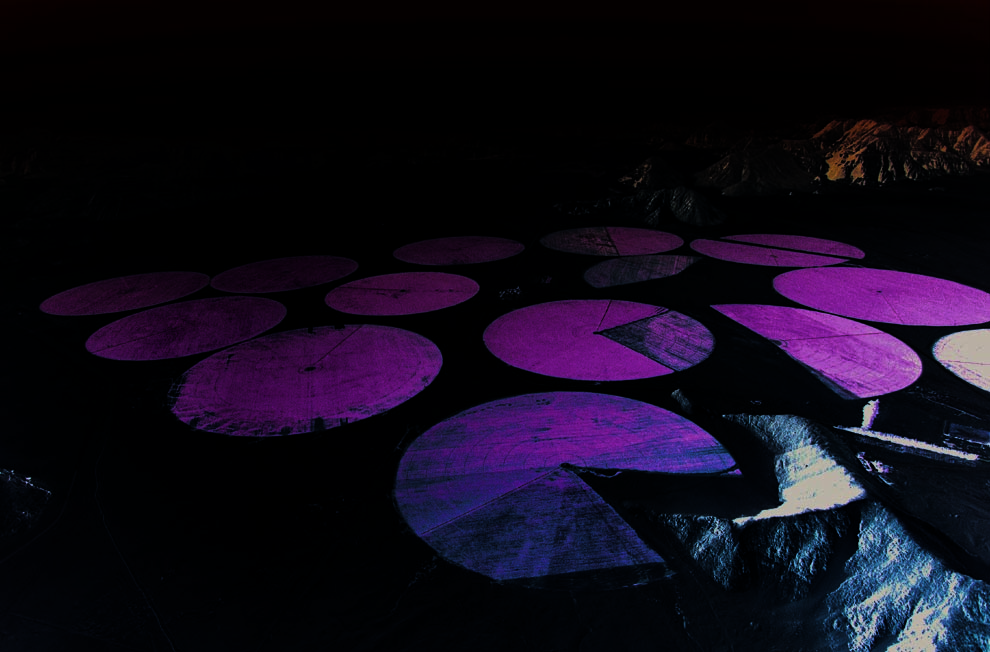

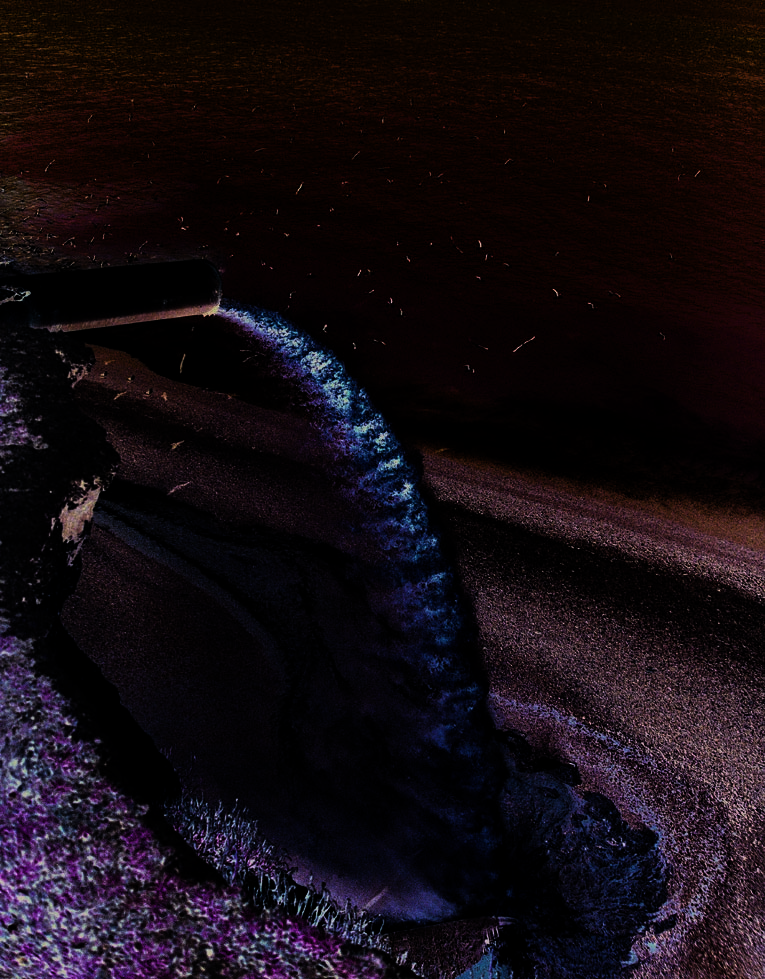

IN THE BARREN DESERT OF WADI RUM CROPS ARE

GROWN ON CIRCULAR IRRIGATED PATCHES OF LAND.

(PHOTO: CORBIS)

Today, freshwater is

used unsustainably

FRESHWATER

in the majority of

the regions studied

SHORTAGE

by GIWA. In two-

thirds of the regions, water is predicted to become scarcer by 2020

due to demand continuing to grow in paral el with increased

agricultural production, and population and economic growth.

Global climate change will exacerbate this situation. On a

global scale, the most widespread and adverse transboundary

consequences result from the modification of stream flow by

dams, reservoirs and river diversions, as well as by land-use

changes in the catchment area. Downstream ecosystems and

riparian communities are severely impacted by changes to the

flow regime of international rivers. Inappropriate subsidies

encourage inefficient water use, such as the growing of water-

intensive crops in water scarce regions.

e growing recognition that entire river basins, estuaries and

coastal areas are single planning units has led to a paradigm

shift of water management towards more integrated approaches.

Demand management was identified as an effective alternative

to building new reservoirs and deeper wel s. ere is a need to

move away from focusing exclusively on the direct economic

benefits of engineered structures to understanding their actual

environmental and socio-economic costs.

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

20

FRESHWATER SHORTAGE

21

Freshwater is a highly valuable resource for a large

BOX 1. TRANSBOUNDARY FRESHWATER RESOURCES

number of competing demands, including drink-

ing water, irrigation, hydroelectricity, waste disposal,

Approximately 60 of global freshwater flows and 50 of the Earth's land sur-

industrial processes, transport and recreation, as wel

face is located within the 263 international river basins.

as ecosystem functions and services. Prior to the 20th

More than 40 of the world's population live within international river basins.

century, human demand for water was relatively smal

Many of the world's largest lakes are transboundary, such as the Caspian Sea,

compared to availability in most parts of the world.

Aral Sea, Lake Chad, Dead Sea, Lake Tanganyika, Lake Victoria and the Great

Water demand dramatical y increased as a consequence

Lakes of North America.

of population and income growth, and the expansion

Transboundary groundwater systems of global significance include the Guarani

of industry and irrigated agriculture, so that demand

aquifer in South America, Chad Formation and Nubian Sandstone aquifer in

now exceeds supply in many developed and develop-

North Africa, and Gangetic Plain Quaternary aquifer in Asia.

ing countries. Today, freshwater scarcity affects more

More than 400 international treaties or agreements related to shared water

than a bil ion people and the integrity of many of the

resources have been signed since 1820, excluding agreements on navigation,

world's ecosystems. e achievement of many of the UN

fisheries, or the demarcation of borders. However, 60 of international basins

Mil ennium Development Goals (MDGs) wil depend

do not have any cooperative management framework.

on the improved management of freshwater resources.

(SOURCE: UNEP 2002)

One goal focuses specifical y on reducing the propor-

tion of people without sustainable access to safe drink-

Overextraction of aquifers is becoming severe in many

ing water and basic sanitation by 50. Managing water in

areas that depend heavily on irrigated agriculture or are

transboundary river basins poses great chal enges and requires

densely populated. e extraction of fossil water from

comprehensive solutions that take into account the needs of

deep aquifers is unsustainable as they will not be refil ed

both upstream and downstream countries (Box 1).

on human time scales. Knowledge of aquifers is insuffi-

e GIWA methodology (see Annex II) provides a

cient and further studies are needed in order to compre-

framework for evaluating three critical freshwater trans-

hensively assess transboundary aquifers.

boundary issues: (i) modification of stream flow; (i ) pol ution Agricultural land is becoming too saline to support

of existing supplies; and (i i) changes in the water table. e

important crops, the salinity of aquifers is too high for

results of the GIWA assessment for freshwater shortage are

human use, and saline waters encroach further up rivers

summarised in the global matrix in Annex III.

during dry seasons.

Land-use changes, including deforestation and the culti-

Global situation and trends

vation of wetlands, affect the water budget, thus causing

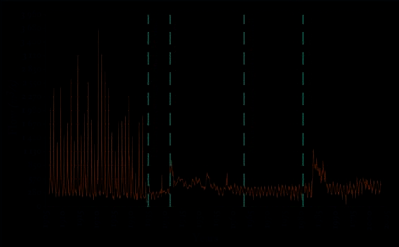

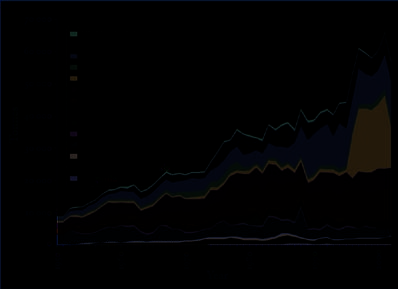

Freshwater shortage was assessed as the priority trans-

floods or droughts in many regions.

boundary concern in more GIWA regions/sub-systems than

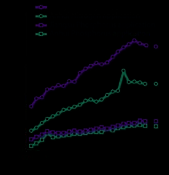

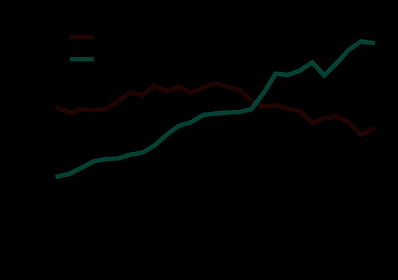

e majority of GIWA regional teams predict that envi-

any other GIWA concern. Many of these regions are arid

ronmental problems related to freshwater shortages will

and either renowned drought-prone basins in Africa or

increase by 2020.

subject to long-term unsustainable water management.

More than half of the regions/sub-systems considered

the overall environmental and socio-economic impacts of

freshwater shortages to be moderate or severe (Figure 1).

ENVIRONMENTAL AND

Impacts of the modification of stream flow caused by

SOCIOECONOMIC IMPACTS

dams or river diversions were more widespread and severe

than those caused by the pol ution of existing supplies or

Modification of stream flow

changes in the water table.

Nineteen GIWA regional teams identified the modification of

Water withdrawals by irrigated agriculture were identi-

stream flow as having severe impacts, particularly in Sub-Sa-

fied by the GIWA regional teams as causing the most se-

haran Africa, North Africa, Northeast Asia, Central America

vere environmental and socio-economic impacts.

and Europe & Central Asia (Figure 3). Table 2 summarises

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

20

FRESHWATER SHORTAGE

21

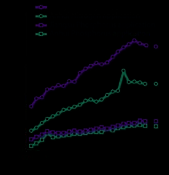

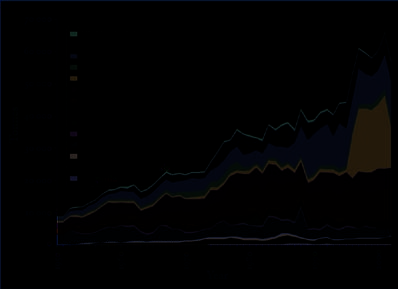

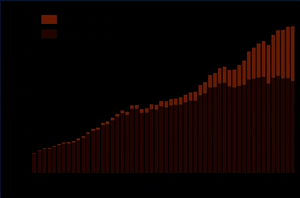

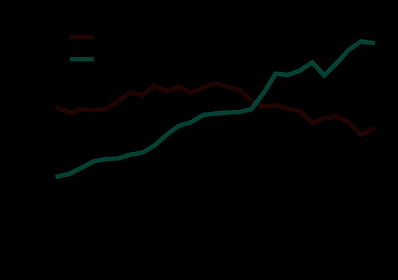

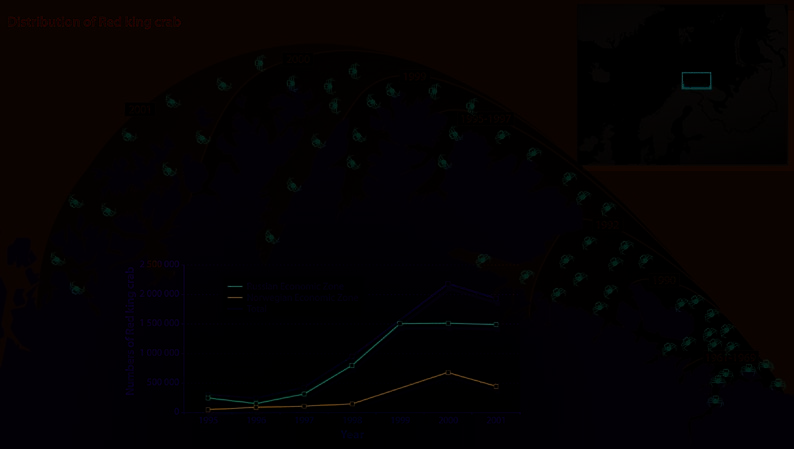

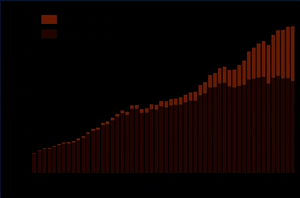

FIGURE 1. OVERALL ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF FRESHWATER SHORTAGE

FIGURE 2. FUTURE ENVIRONMENTAL TRENDS OF FRESHWATER SHORTAGE

the environmental and associated socio-economic impacts as-

Dams change flow patterns by storing water in res-

sessed by GIWA for a selection of transboundary river basins.

ervoirs during the wet season and releasing part of it dur-

Changes in the flow regime were principal y attributed

ing the dry season. e biodiversity of riparian and aquatic

to the development of large dams (e.g. the Colorado River,

habitats changes in response to the alteration of the flow

Figure 4). River diversions, inter-basin transfers and other

regime. Dams can also obstruct migration routes and re-

structures designed to supply water and energy also modify

duce fish spawning habitat. For example, dams on the Volga

stream flow.

River (Caspian Sea/23) have reduced the spawning habitat of

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

22

FRESHWATER SHORTAGE

23

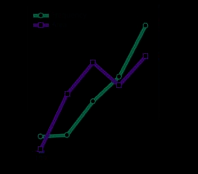

FIGURE 3. IMPACTS OF MODIFICATION OF STREAM FLOW

Caspian sturgeon, and these fish are now predominantly re-

the storage capacity of reservoirs, thus intensifying competi-

cruited in hatcheries.

tion over water supplies (Agulhas Current/45a). In the Niger

Fragmentation of rivers results in the trapping of sedi-

River (Guinea Current/42c), sedimentation in upstream res-

ments in reservoirs which can lead to downstream ecological

ervoirs causes coastal erosion and reduces nearshore produc-

changes and erosion in floodplains, deltas, estuaries and the

tivity as fewer sediments and nutrients reach the coast.

coastal zone. Land use changes, particularly deforestation,

In addition to fragmentation and changed flow re-

modify sedimentation and flooding regimes. e accumula-

gimes, evaporation and water consumption have signifi-

tion of sediments behind dams can affect downstream natu-

cant consequences for downstream ecosystems and societies.

ral resources and associated livelihoods, and may impede the

Global y, irrigated agriculture accounts for around 70 of

efficiency of dam infrastructure and reduce the storage capac-

freshwater withdrawals, fol owed by industry (21) and do-

ity of reservoirs. For example, in the Save River in Zimba-

mestic uses (10). Not all water withdrawals are `consumed',

bwe, soil erosion and sedimentation has significantly reduced

as return flows re-enter the hydrological system downstream.

Irrigated agriculture, however, returns only 30 of its water

withdrawals, while industrial and domestic users return

85-90 (FAO 2002). In Namibia's Eastern National Water

Carrier canal, more than 70 of the water is lost through

evaporation (Benguela Current/44). Freshwater shortage in

the Benguela Current region il ustrates the problems faced by

arid coastal environments worldwide (Box 2).

Loss of freshwater inflow to enclosed water bodies has

resulted in dramatic changes to many ecosystems, notably the

shrinking of the Aral Sea/24 and the Dead Sea (Jordan/51)

(Box 3). In the inland areas of the Canary Current/41 region,

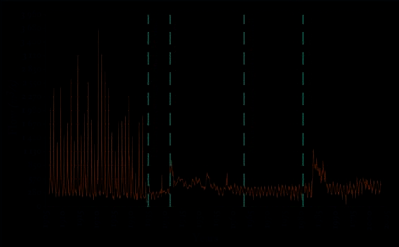

FIGURE 4. FLOW OF THE COLORADO RIVER BELOW THE

the Volta River Basin (Guinea Current/42b) and the Lake

HOOVER DAM 1905-2003

(SOURCE: USBR 2002)

Chad/43 Basin, reduced rainfal over the last few decades

CHALLENGES TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS: REGIONAL ASSESSMENTS IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

22

FRESHWATER SHORTAGE

23

TABLE 2. IMPACTS OF MODIFICATION OF STREAM FLOW IDENTIFIED IN GIWA REGIONS

GIWA region River basin or

hydrological system

Environmental impacts

Social, economic and health impacts

Decreased sediment transport to the coast

Lack of potable water

Gulf of

Erosion of the Colorado River Delta

Loss of crops

California Colorado River

Loss of wetlands

Loss of fisheries

Loss of endemic plants

Loss of traditional livelihoods

b Gulf of

Rio Grande/Rio Bravo,

Mexico

river and estuary

Increased salinity of estuarine habitats

Impacts on coastal fisheries

Conflicts over water resources

Yalu River, Huai River,

Reduction in water flow

a Yel ow Sea Yongsan River, Taedong Pol ution degrading nearby habitats and leading to annual mass fish kil s

Interruptions in water supply

River, Imjin River, Han

Pol ution of water supplies

Increase in infectious diseases

River, Kum River

Salinisation of coastal aquifers

Displacement of people

c Brazil

São Francisco, river and

Decreased sediment transport to the coast and coastal erosion

Loss of traditional livelihoods

Current

estuary

Reduced primary productivity

Reduced availability of fish

Navigation impediments

Loss of farmland and infrastructure

b Guinea

Reduced agricultural output

Current

Volta River

Decreased sediment transport to the coast and erosion

Displacement of people

Loss of marine biodiversity

Increased water-related diseases

Loss of traditional sites

Komadugu-Yobe River

Basin

Loss of floodplain ecosystems and wetlands

Reduced productivity of farmland

Degradation of grazing lands

Reduced availability of fish

Chari-Logone River

Acute freshwater shortage

Basin

Loss of floodplain ecosystems and wetlands

Lake Chad

Food insecurity in downstream areas

Increased water-related diseases

Shrinking of Lake Chad

Upstream/downstream conflicts

Lake Chad

Loss of plant species

Political disputes

Decreased fish stocks and diversity

Displacement of people

Increased vulnerability to flooding

Benguela

Increased water-related diseases

Current

Orange-Vaal River Basin Changed hydrological regime

Displacement of people

Disruption of family and community structures

d Somali

Displacement of people

Coastal

Rufiji/Ruvuma River

Changed flow and flood patterns

Malnutrition during periods of relocation

Current

Basin

Increased salinity in the Rufiji Delta

Social conflicts

Deteriorating human health

Amu Darya River,

Shrinking of the Aral Sea

International disputes

Aral Sea

Syr Darya River,

Fish extinctions

Loss of agricultural productivity

Aral Sea

Salinisation of soil and water resources

Loss of fisheries

Displacement of people

Jordan

Jordan River, Dead Sea

Shrinking of the Dead Sea

Lack of potable water

Salinisation of water resources

Increased water-related diseases

NOTE: THE TABLE PRESENTS A SELECTION OF REGIONS WHERE THE GIWA ISSUE MODIFICATION OF STREAM FLOW HAS BEEN ASSESSED AS SEVERE.

BOX 2. DESERTS BEHIND THE SEA: FRESHWATER SHORTAGE IN THE BENGUELA CURRENT REGION

In GIWA region 44, the land areas adjacent to the Benguela Current are