Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment

1b Arctic Greenland

15 East Greenland Shelf

16 West Greenland Shelf

Greenland Institute of Natural Resources

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Report editor: UNEP Collaborating Centre on Water and Environment (UCC-Water)

Contributors: Søren Anker Pedersen, GINR (Compiler and editor),

Jesper Madsen, NERI (Co-editor), Mogens Dyhr-Nielsen, UCC-Water (Co-editor)

Global International Waters Assessment

Arctic Greenland, East Greenland Shelf, West Greenland Shelf,

GIWA Regional assessment 1b, 15, 16.

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2004 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-940X

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and

in any form for educational or non-profi t purposes without

special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this

publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the

United Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2004. Pedersen, S.A., Madsen, J. and M. Dyhr-Nielsen, Arctic

Greenland, East Greenland Shelf, West Greenland Shelf, GIWA

Regional assessment 1b, 15, 16. University of Kalmar, Kalmar,

Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and do not necessarily refl ect those of UNEP. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating

agencies concerning the legal status of any country, territory,

city or areas or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information

herein is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not

warrant its completeness or accuracy. This particular report in the

GIWA Regional assessments series has been edited by the UNEP

Collaborating Centre on Water and Environment (UCC-Water).

Contents

Preface 9

Executive summary

10

Regional defi nition

12

Boundaries of the regions

12

Physical characteristics

12

Socio-economic characteristics

20

Conclusion

23

Assessment 24

Freshwater shortage

25

Pollution

25

Habitat and community modifi cation

30

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

33

Global change

36

Priority concerns

38

Causal chain analysis

40

Introduction

40

Immediate causes

40

Root causes

45

Conclusion

47

Policy options

49

Key issues and causes

49

Options for policy intervention

49

Conclusions

54

References 55

Annexes 62

Annex I List of contributing authors and organisations involved

62

CONTENTS

7

List of figures

Figure 1

Boundaries of the Arctic Greenland, East Greenland Shelf and West Greenland Shelf regions.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Figure 2

Greenland map showing a typical situation during the winter. The locations of the larger polynyas around Greenland are shown. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Figure 3

Ocean surface currents. Blue arrows indicate cold currents and red arrows show warm ones. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Figure 4

Gross primary production from July to August is greatest along edge of the ice off East Greenland and Labrador and near the coast where bottom

water is brought to the surface by upwelling. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Figure 5

(a) Annual pelagic primary production versus length of productive open water period. b) Geographical location of investigations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Figure 6

Catches of fish from region 16, West Greenland Shelf (upper figure) and region 15, East Greenland (lower figure). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Figure 7

National parks and protected areas indicated by their name. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Figure 8

Population pyramid for Greenland, 2001.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Figure 9

Mercury (left) and PCB (right) concentrations in human blood. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Figure 10 Polar bears live in ice-covered fjords and seas, their most important prey being ringed seals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Figure 11 Walruses occur in coastal waters. They often rest on small, sturdy ice floes. Thus, these floes are part of their habitat. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Figure 12

Time series of the winter NAO index (a), winter air temperature (b), sea temperature (c), landings of Atlantic cod (d), and northern shrimp (e)

in the West Greenland LME (16), 1950-2000. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Figure 13

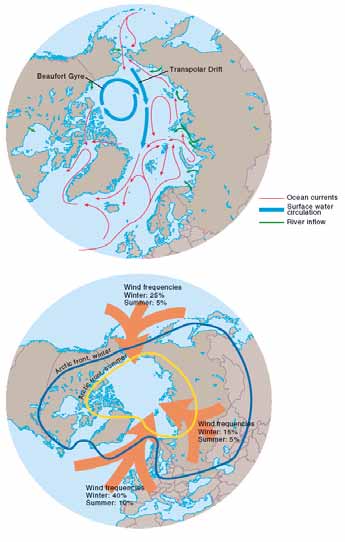

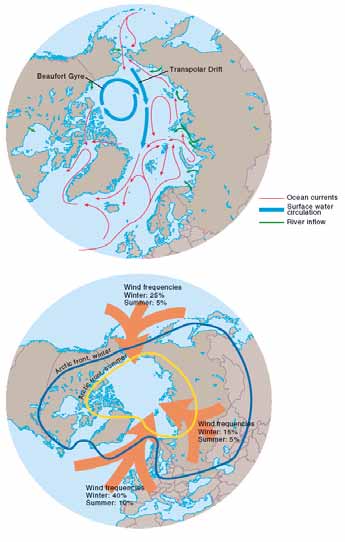

Pathways for pollutants transported to Greenland. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

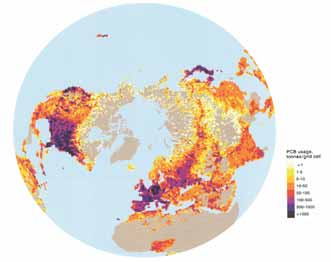

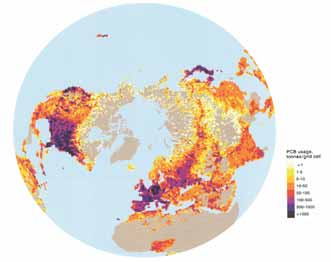

Figure 14 Estimated cumulative global usage of PCBs (1930-2000). Most of the use was in the northern temperate region.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Figure 15

Causal chain analyses regarding overexploitation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Figure 16

Causal chain analyses regarding chemical pollution. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

List of tables

Table 1

Scoring tables for the Arctic Greenland, East Greenland and West Greenland regions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Table 2

Heavy metals in the environment in Greenland. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Table 3

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the environment in Greenland. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Table 4

Other contaminants of concern. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Table 5

Human health impacts of contaminants in Greenland. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Table 6

Reported number of individuals by part-time and full-time hunters, 1996-2000. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Table 7

Calculated number of belugas in the area Qeqertarsuaq og Maniitsoq, West Greenland. From aerial observations.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Table 8

Prioritisation of impacts of Major Concern at present and in 2020 in Arctic Ocean (1), East- and West Greenland Shelf (15 and 16). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

8

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

Preface

Globally, people are becoming increasingly aware of the degradation

Two task team meetings were held in 2003:

of the world's water bodies. The need for a holistic assessment of

1) August 15, at the National Environmental Research Institute in

transboundary waters in order to respond to growing public concern

Roskilde, Denmark, and

and provide advice to governments and decision makers regarding

2) September 3, at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources in Nuuk,

management of aquatic resources has been recognised by several

Greenland.

international bodies focusing on global environment. To compile a

global overview, the Global International Water Assessment (GIWA) has

A number of selected experts were participating in these task team

been implemented by the United Nations Environment Programme

meetings. Other selected experts were unable to attend to the

(UNEP) in conjunction with the University of Kalmar, Sweden

meetings. The experts consulted for inputs and reviews of this report

(www.giwa.net).

are presented in Annex 1. The report was peer-reviewed by Dr. Henrik

Sparholt and Dr. Raphael V. Vartanov.

The importance of the GIWA has been underpinned by the UN

Millennium Development Goals adopted by the UN General Assembly

The report has been compiled and edited by:

in 2000 and the Declaration from the World Summit on Sustainable

Søren Anker Pedersen, GINR (Compiler and editor)

Development in 2002. The development goals aimed to halve the

Jesper Madsen, NERI (Co-editor)

proportion of people without access to safe drinking water and basic

Mogens Dyhr-Nielsen, UCC-Water (Co-editor)

sanitation by the year 2015. WSSD also calls for integrated management

of land, water and living resources and, by 2010 the Reykjavik

Declaration on Responsible Fisheries in the Marine Ecosystems should

be implemented by all countries that are party to the declaration.

This report presents the results of GIWA assessments of the three

Greenlandic GIWA regions Arctic Ocean (1), East Greenland Shelf (15),

and West Greenland Shelf (16). The report is the Greenland contribution

to GIWA and it is funded by the Danish Environmental Protection

Agency as part of the environmental support programme DANCEA

Danish Cooperation for Environment in the Arctic. The report has been

carried out in collaboration between National Environmental Research

Institute (contractor), Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, and

UCC-Water.

The report is based on the GIWA Methodology: "STAGE 1: Scaling and

Scoping" and "Causal chain analyses" (see www.giwa.net).

PREFACE

9

Executive summary

Greenland and its surrounding marine waters comprise a unique

where they are bioaccumulated in tissues of animals. Because these

arctic and fairly undisturbed ecosystem of global signifi cance. 85%

are important local diet items, both animals and human health might

of Greenland is covered by a continuous icecap, and the population

be aff ected. Over the next 20 years, environmental and human

of less than 60,000 lives in small towns and settlements along the

health impacts from pollution are expected to increase, unless strict

coast. The population is traditionally highly dependent on the marine

regulations and internationally adopted environmental protection

ecosystems, and also today, the economy of Greenland is strongly

measures are implemented.

related to the productivity of the marine waters. In the 20th century,

Greenland has experienced two major transitions, from seal hunting

With the large importance of the fi shing sector (locally as well as

to cod fi shery, then from cod to shrimp fi shery. Both aff ected the

internationally), unsustainable exploitation of fi sh has also been

human population centers of West Greenland and the economy. The

identifi ed as a key concern in both East Greenland Shelf and West

economic transitions refl ected large-scale shifts in the underlying

Greenland Shelf. Southern Greenland waters are moderately impacted,

marine ecosystems, driven by interactions between climate and

and due to the remoteness , the Northern waters are not aff ected

human impacts.

at all.

Accordingly, the coastal and marine waters hold by far most of

In the Northern and eastern waters, changes in ice cover and water

the international environmental aspects in relation to the Global

temperature due to climatic heating cause increasing impacts on these

International Water Assessment, whereas land and river issues are

unique ecosystems, in particular the habitats of endangered species

of minor or no importance. The eastern waters are characterized

like the polar bear.

by southern currents from the Arctic basin, and in the spring and

summer large amounts of sea ice drifts south. The western waters are

The key causes for the toxic pollution are related to toxic emissions to

infl uenced by a northern current, mixed by the cold eastern current

water and air in industrial areas in Northern Asia, Europe and America.

and the warmer waters from the Irminger current. The oceanographic

These sources are outside the control of the Greenland authorities and

and sea ice conditions are closely linked to climate variability. The last

can be controlled by international agreements only.

decades warming of the northern hemisphere has reduced summer ice

cover and increased open-water periods in East Greenland. But in the

The issue of overexploitation is caused by inappropriate management,

same period regional lower temperatures has increased ice cover, and

due to a lack of understanding of how the marine resources react

reduced open-water periods in West Greenland. The arctic ecosystems

to the combined pressures of fi sheries and climate change. The

are fragile and their stability is closely related to ocean temperature and

disappearance of the cod and the replacement by shrimp has been

to changes in ice cover.

related to changes in water temperature, but the actual impact of

the fi sheries are diffi

cult to determine. Accordingly, there is a need

A major environmental concern of the marine waters around Greenland

to improve the scientifi c understanding of the marine ecosystems

have been identifi ed to be chemical and toxic pollutants. Long-range

around Greenland, and to use these results in an ecosystems approach

transport of toxic contaminants reach the coastal waters of Greenland,

to fi sheries management.

10

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

It is also apparent that the potential future impacts of global warming

on the fragile arctic ecosystems can be mitigated only by control of the

release of greenhouse gasses by the larger consumers of fossil fuels in

the developed world. A continued international eff ort to control these

sources is mandatory to save the ecosystems of the Northern waters,

including the large mammals like the polar bear and the walrus.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

Regional defi nition

This section describes the boundaries and the main physical and

Norway (180 km south of Anchorage, Alaska, USA). The ice-free parts

socio-economic characteristics of the region in order to defi ne the

alone have a topography dominated by alpine areas and cover an area

area considered in the regional GIWA assessment and to provide

of 2 175 600 km2.

suffi

cient background information to establish the context within

which the assessment was conducted.

85% of Greenland is covered by a continuous, slightly convex ice cap,

which is the world's second-largest ice sheet. In a borehole drilled in

the central part of the ice cap, the drill reached the bedrock in a depth

of 3 030 m. The remaining 15% of the island is a narrow stretch of land

Boundaries of the regions

between the ice cap and the sea, where fl ora and fauna exists and the

people live mainly in the coastal areas, with access to open water.

The marine waters of Greenland holds by far most of the international

aspects in GIWA, whereas land and river issues are of minor or no

The coast around Greenland is dominated by bedrock shorelines

importance. Greenland holds three GIWA regions: Arctic (1), East

with many skerries and several archipelagos. Very large diff erences in

Greenland Shelf (15), and West Greenland Shelf (16) (Figure 1). It was

depths can be found within a short distance in the coastal zone. Some

agreed among task team experts to assess Greenland waters in these

of the world's largest fj ord complexes are found in East Greenland, e.g.

three predefi ned regions in order to maintain the comparability with

Kejser Franz Josephs Fjord and Scoresby Sund, leading out north of the

the other UNEP/GIWA regions and to use the GIWA methods. However,

Denmark Strait. In several places the icecap reaches the coast as glaciers

there are major diff erences between ecosystems from south to north

at the heads of fj ords; so called icefj ords. Deep fj ords often continue as

within regions 15 and 16 due to diff erences in physical characteristics,

deep channels outside the coastal line, dividing the off shore banks.

species compositions, and community structures on both the East and

West Greenland Shelf.

Greenland is located in the Arctic. That means that the average

temperature in July does not exceed 10°C, that there is permafrost

in most regions, so only the top layers of soil thaw in the summer,

and there are no forests. In southwest, however, there is generally no

Physical characteristics

permafrost and at a few locations close to the inland ice the average

temperature in July may exceed 10°C. The country can be divided from

Geography (location, geology, climate)

south to north into sub-arctic, low-Arctic and high-Arctic climate zones.

Geographically, Greenland is part of the North American continent,

The mean summer temperatures on both the west and the east coast

geopolitically, a part of Europe. Greenland is the biggest island in

diff er by only a few degrees from south to north, despite a distance of

the world. It stretches from Nunap Isua (Kap Farvel) in the south at

more than 2 600 km. The reason for this is the vast iceshield on the one

59°46' N lat to Odaap Qeqertaa (Odak Island) at 83°40' N lat (Figure 1).

hand, and the summer midnight sun in north Greenland on the other.

Odaap Qeqertaa lies only 700 km from the North Pole, and Kap Farvel,

Conversely, winter darkness and the absence of warm sea currents from

2 600 km further south, is at the same latitude as Oslo in southern

North and East Greenland mean that the temperature during the winter

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

Svalbard

Odaap Qegertaa

1b. Arctic Greenland

Thule

G R E E N L A N D S E A

Canada

B A F F I N B A Y

Greenland

16. West

Scoresbyund

Greenland

Shelf

Godhavn

D A V I S S T R A I T

D E N M A R K

S T R A I T

Iceland

Angmagssalik

Godthab

Elevation/Depth (m)

15. East

4 000

Greenland

2 000

Shelf

1 000

500

L A B R A D O R S E A

100

Nunap Isua

C

0

I

-50

-200

T

-1 000

N

-2 000

A

L

0

500 Kilometres

A

T

© GIWA 2004

Figure 1

Boundaries of the Arctic Greenland, East Greenland Shelf and West Greenland Shelf regions.

period diff ers considerably from north to south, average temperatures

the months of the year except deep inside the large fj ords in southern

in February 1961-1990: -30.9°C in the north and -3.9°C in the south (see

and western Greenland during the summer months. The "frostfree"

www.dmi.dk).

period in southern Greenland varies from 60 to 115 days per year.

The highest temperature offi

cially recorded in Greenland since 1958

The coldest place in Greenland is naturally on the ice cap, where the

is 25.5°C. It was recorded near the "ice cap" in Kangerlussuaq (West

temperature can fall to below -70°C. Temperatures in Greenland have

Greenland) in July 1990. In Greenland, frost can occur in principle in all

shown a slightly increasing trend for the last 125 years, although, on a

REGIONAL DEFINTION

13

shorter time scale, temperatures have generally fallen since the 1940s

2003; Heide-Jørgensen and Laidre, 2004). In the white stretch of frozen

(Anon, 2003a, Figure 2.10). This has been most marked on the west

Arctic Sea, there exist many winter refugia or "microhabitats" for air-

coast, where a temperature rise trend has only been seen over the last

breathing marine animals. Several species seek access to open water

few years. On the east coast, however, there has been an increasing

leads and productive foraging opportunities for many months of the

trend since the 1970s.

year. The refugia range widely in size, from a few hundred meters to

many kilometres of vast open water. They remain ice-free during even

Recorded precipitation in Greenland decreases with rising latitude

the coldest period of winter and are generally surrounded by solid sea

and from the coast to the inland area. In the south and particularly

ice. Often these areas are annual recurrent `polynyas' (the Russian word

in the southeastern region, precipitation is signifi cant with average

for `open water area surrounded by ice'), variable shore leads and cracks,

annual precipitation ranging from 800 to 2 500 mm along the coasts.

or tidal- and/or wind-driven openings in the consolidated pack ice.

Further inland, towards the ice cap, considerably less precipitation is

What defi nes these microhabitats is that they occur predictably in the

recorded.

same locations year after year, independent of how they are generated

and maintained. This geographical and temporal predictability permits

In the northern regions of Greenland there is very little precipitation,

numerous Arctic sea birds and marine mammals to utilise open water

from around 250 mm down to 125 mm per year. In the northeastern

during winter, when survival in the Arctic sea ice is most critical. Many

most coastal areas there are "arctic deserts", i.e. areas that are almost free

of these open water habitats demonstrate conspicuous levels of

of snow in winter, and where evaporation in summertime can exceed

production, generally due to large-scale upwelling events along the

precipitation.

ice edge driven by the absence of ice providing early availability of light

for photosynthesis. This widely attracts sea birds and marine mammals

Not surprisingly, snow is very common in Greenland. In principle, in the

that seek to benefi t from zooplankton production and associated fi sh

coastal region it can snow anytime during the year without snow cover

abundance in these areas (Heide-Jørgensen and Laidre, 2004).

necessarily forming. The winter snow depth is greatest in southern

Greenland, averaging from one to more than two metres in all the

Species that utilise open water winter refugia include Arctic cetaceans,

winter months and sometimes reaching up to six meters.

pinnipeds, sea birds and polar bears and their winter behavioural

preferences are specifi c to requirements for survival and reproductive

The prevailing patterns of wind direction, especially in winter,

success (Heide-Jørgensen and Laidre, 2004). One of the largest winter

transport air masses from industrialised areas to the Arctic. The cold

refugia is the North Water Polynya (NOW) found during winter in Smith

Arctic climate seems to create a sink for pollutant compounds (certain

Sound and the northernmost Baffi

n Bay (Figure 2). NOW is utilised

heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants), resulting in a so-called

during winter and spring by approximately 13 000 belugas or white

bio-accumulation in higher animals (fi sh, sea birds, marine mammals),

whales (Delphinapterus leucas) (who undertake a northbound migration

causing concern for human health of Greenlanders consuming these

to this locality from Lancaster Sound in the fall), thousands of narwhals

animals.

(Monodon monoceros), and 30 million little auks (Alle alle) feeding in the

area prior to the breeding season. Alternate and smaller open water

The Greenland ice cap, icebergs, and sea ice

localities of great importance are situated over shallow banks, such

The Greenland ice cap (1.7 million km2) holds 9 % of the world's

as Store Hellefi ske Bank in West Greenland, containing vast benthic

freshwater. The Greenland ice cap produces about 300 km3 of

resources utilised by species such as king eiders (Somateria spectabilis)

icebergs per year. About 10 % of all Greenland's icebergs stem from

and common eiders (Somateria mollissima) and walrus (Odobenus

one particularly active glacier near the town Ilulissat ("Icebergs" in

rosmarus) with limited diving abilities. Hundred of thousands of thick

Greenlandic) in Disko Bay, This glacier (Sermeq Kujalleq) is the most

billed murres (Uria lomvia) from Canada, Greenland and Svalbard over

prolifi c glacier in the Northern Hemisphere and produces 22 million

winter in smaller regions along the productive coastal open water area

tonnes of ice each day (Chisholm and Parfi t, 2002).

in West Greenland.

The extensive sea ice is one of the most characteristic and most

Oceanography

important features of the Arctic Ocean, North Greenland and adjacent

Comprehensive descriptions of the physical oceanography of the

waters. Sea ice plays a decisive role for marine productivity and life in

Greenland waters have been given by Buch (1990), Valeur et al. (1996),

Arctic Greenland (e.g., Rysgaard et al., 2003; Born et al., 2003; Wiig et al.,

Buch et al. (2004), and Rudels et al. (2002).

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

© GIWA 2004

Odaap Qegertaa

Nares strait

Northeast Water

North water

F R A M S T R A I T

ARES STRAIT

N

G R E E N L A N D S E A

W

est

Greenla

Kangertittivaq

n

Scoresby Sund

d

curr

r r e n t

e

n

c u

t

d

n

t

l a

n

n

e

e

rr

t

r e

u

n

G

c

r e

t

r

s

ic

u

a

t

c

E

n

r

la

o

t

d

A

a

h

r

t

b

r

a

o

© GIWA 2004

L

N

Polynyas

Figure 3

Ocean surface currents. Blue arrows indicate cold

currents and red arrows show warm ones.

0

500 Kilometres

100% Icecover January

Nunap Isua

(Source: Modified from Born and Bøcher, 2001)

Figure 2

Greenland map showing a typical situation during the

winter. The locations of the larger polynyas around

Greenland are shown. `Polynyas' is the Russian word for

the warmer Irminger Current. These two water masses mix intensely.

`open water area surrounded by ice'.

The hydrographic conditions along West Greenland depend greatly

(Source: Born and Bøcher, 2001)

on the relative strengths of these two currents. The West Greenland

East Greenland

Current, which fl ows over the Greenland shelf, continues northward

The surface layer in the eastern part of the Greenland Sea is dominated

until it reaches a latitude of about 65-66° N in the Davis Strait. At this

by the northward fl owing Norwegian Atlantic Current, an extension of

point, a part of it turns westward and unites with the south fl owing

the North Atlantic Current. Waters from the Arctic Basin are transported

Baffi

n Current along the Canadian east coast, and a part continues

southward through the Fram Strait along the east coast of Greenland

northward in Baffi

n Bay.

to the Greenland Sea (Figure 3). The East Greenland Current fl ows over

the Greenland shelf. During spring and early summer it carries large

North Greenland

amounts of pack ice along with it.

Baffi

n Bay receives polar water from the Arctic Ocean through the Nares

Strait and the Canadian Archipelago. This polar water fl ows southward

The East Greenland Current fl ows southward along the coast of East

along the eastern Canadian coast. Baffi

n Bay is covered by ice during

Greenland and rounds Cape Farewell. A branch of the North Atlantic

winter, and in very cold winters, the ice can cover the whole Davis

Current, known as the Irminger Current, turns westward along the west

Strait. In summer the ice breaks up and drifts south along Canada's

coast of Iceland. Part of the current turns further towards Greenland,

east coast.

where it fl ow southward parallel to the East Greenland Current down to

Cape Farewell, where it joins the East Greenland Current (Figure 3), and

Climate-oceanography-sea ice

fl ows up the west coast, securing largely open water in the harbours of

The oceanographic and sea ice conditions around Greenland are linked

Southwest and West Greenland.

to climate variability and the changes in the distributions of atmospheric

pressures on the northern hemisphere (e.g. Buch et al., 2001, 2004;

Southwest and West Greenland

Serreze et al., 2000; Johannesen et al., 2002; Macdonald et al., 2003). For

The water masses fl owing northward along the West Greenland coast

example the winter (December-March) North Atlantic Oscillation Index

originate partly from the cold East Greenland Current, and partly from

(NAO-index) tends to be positively correlated with next years winter sea

REGIONAL DEFINTION

15

ice concentrations in West Greenland, but negatively correlated with

mg C per m2 per day

next years sea ice concentrations in Northeast Greenland (Stern and

<100

Heide-Jørgensen, 2003). The last decades warming of the northern

100-200

hemisphere has given reduced summer ice cover and increased open-

200-300

water periods in East Greenland, however, at the same time regional

>300

lower temperatures, increased ice cover, and reduced open-water

periods has been observed in West Greenland (e.g. Stern and Heide-

Jørgensen, 2003).

Marine ecosystems

Basic information on biological diversity and marine ecosystems in

Greenland has been given in Jensen (1999) and Born and Bøcher (2001).

Specifi c research and reviews of potential environmental impacts and

status of species and their habitats have recently been given in reports

and scientifi c papers e.g. Heide-Jørgensen and Johnsen (1998), Riget et

al. (2000), Buch et al. (2001), Petersen et al. (2001), Glahder et al. (2003),

Mosbech et al. (1996, 1998), Mosbech (2002), Pedersen (2003), Møller et

al. (2003), Born et al. (2003), Wiig et al. (2003), Buch et al. (2004), Rysgaard

et al. (2003), Hansen et al. (2003), Heide-Jørgensen and Laidre, 2004).

Primary production

Figure 4

Gross primary production from July to August is

greatest along edge of the ice off East Greenland and

The annual pelagic primary production in the low arctic south Greenland

Labrador and near the coast where bottom water is

waters averages 40-80 g C/m of sea surface. Annual productions as high

brought to the surface by upwelling.

as 605 g C/m have been registered. This is more than in most boreal

(Source: Nielsen, 1958 in Born and Bøcher, 2001)

and tropical waters, but still compares poorly with annual productions

of 5.5 kg C/m near Antarctica and over 3.5 kg C/m off the Peruvian coast.

While the surface community in the open water is nutrient depleted in

Sea ice, ocean currents, light, nutrients, temperature, and grassing by

the late summer, the continuous supply of nutrients from the melt water

herbivores are primary factors determining the distribution of marine

at the marginal ice zone can support a high phytoplankton biomass.

productivity and animal life. Areas, in which water masses are vertically

Thus blooms can be observed at the ice edges throughout the season

mixed, with a continuous supply of nutrients to the surface, are

while it is more episodic in the open water.

especially productive. One example is the front area between polar

and Atlantic water masses that predominates off the southeast coast

To understand the carbon drawdown, it is essential to have a good

of Greenland. Another is the mixed water mass on the banks off West

description of the structure and succession of the zooplankton of

Greenland, where the surface layers are well supplied with nutrients

the area. The zooplankton infl uences the carbon dynamics in several

throughout the summer (Figure 4).

ways; by vertical migration, through grazing activity and by acting as

accelerators of sedimentation of organic matter through production

The annual cycle in primary production in the seas of Greenland is

of faecal material. During the last decade, the views on high latitude

normally initiated in May reaching peak biomasses in June. Large

pelagic food web structure have changed.

diatoms dominate the spring bloom, but depending on the nutrient

availability, the fl agellate Phaeocystis may also contribute. After the

Pelagic food web

spring bloom where silicate or nitrate is depleted from the surface

The present knowledge of pelagic food chain structure in high

layer, the phytoplankton biomass is low and dominated by autotrophic

latitude ecosystems is primarily based on sampling with coarse nets

fl agellates < 10 µm.

(>200 µm) ignoring the smaller components of the food web. However,

use of nets with smaller mesh size has documented that the smaller

Obviously there are signifi cant regional diff erences in the timing and

copepod species can contribute signifi cantly to standing stock of the

composition of the spring bloom within the northern North Atlantic.

grazer community, especially after the oldest Calanus stages have

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

left the surface layer. During the recent cruises in connection to the

removing and/or inhibiting the algae at the sea ice-water interface

Danish Global Change Program in the Greenland Sea, a pronounced

through physical disturbance and exposure to freshwater. Thus, seen

shift in the copepod community was observed from June to August;

on an annual scale, the primary production of sea ice algae in Young

in June Calanus dominated while the small copepod species and

Sund was <1% of the pelagic primary production.

developmental stages of Calanus took over in August. It is important to

keep in mind that the Calanus species have a 2-4 year life cycle while

In Young Sund the phytoplankton community was dominated by

the smaller species likely go through 2-3 generations per year. So the

diatoms in the surface samples as well as in the subsurface bloom

turnover of the copepod community and grazing rates in August is

succeeding the spring bloom. Pelagic primary production was limited

much higher than in June.

by light during sea ice cover. After break-up of the sea ice, silicate initially

limited primary production in the surface water due to a well established

Knowledge of the role of the microbial food web in the Arctic has

pycnocline, and maximum photosynthesis occurred in a subsurface

been limited because the microbial loop in cold water ecosystems

layer at 15-20 m depth. In August, production was displaced to deeper

has been considered less important than at lower latitudes. However,

water layers presumably due to nitrogen limitation. The carbon

recent comprehensive investigations in Disko Bay, West Greenland, have

budget describing the fate of the annual pelagic primary production

documented that bacterioplankton and unicellular zooplankton also

revealed that the pelagic production was tightly coupled to the grazer

play a prominent role in the food web of Arctic ecosystems (Hansen

community since total consumption by the grazer community. The

et al., 2003).

classical food web dominated this northeastern Greenlandic fj ord

and it was estimated that copepods account for >80% of the grazing

Young Sund

pressure upon phytoplankton (Rysgaard et al., 1999). Based on this

Since 1994 there has been an extensive research activity in the high

study and other values of annual pelagic primary production and sea

Arctic fj ord Young Sund (74°N) on the northeast coast of Greenland

ice cover found in the literature, annual pelagic primary production

(Rysgaard et al., 2003). In the Young Sund estuary, sea ice algae, primarily

in the Arctic was found to increase with the length of the open water

diatoms, were heterogeneously distributed in the sea ice both vertically

light period (Figure 5). Rysgaard et al. (2003) proposed future increase

and horizontally. Annual ice algal production at the sea ice-water

in the annual pelagic primary production, secondary production, and

interface in Young Sund may be highly variable and regulated by the

hence food production for higher trophic level animals in a wide range

thickness of snow cover. Primary production was <0.01 g C/m during

of Arctic marine areas, as a consequence of reduction and thinning

1998-1999. Compared to other coastal fast ice areas in the literature

of sea ice cover due to global warming. The reduction in sea ice may

this rate seems low but comparable to measurements further out in

be a benefi t to some marine mammals e.g. Atlantic walruses (Born et

the Greenland Sea. The low biomass and productivity in Young Sund

al., 2003), but probably not for others e.g. polar bears (Ursus maritimus)

was caused by a combination of poor light conditions due to snow

(Wiig et al., 2003).

cover and freshwater drainage from melt ponds and river discharge

120

)-1

yr

100

-1

(g C m

80

tion

oduc

y pr

60

40

20

Annual pelagic primar

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Productive open water period (months)

© GIWA 2004

Figure 5 (a) Annual pelagic primary production versus length of productive open water period. b) Geographical location of investigations.

Further details are given by Rysgaard et al. (1999)

REGIONAL DEFINTION

17

Due to physical diff erences and because diff erent species have diff erent

600

ranges of temperature and habitat tolerance there are diff erences

Other fish and shellfish

in species composition and community structure of the marine

Northern shrimp

500

Greenland halibut

ecosystems from south to north along East and West Greenland.

Wolffish

400

Redfish

Water temperatures and sea ice distributions play a decisive role in

Atlantic cod

determining the distribution of fi sh, sea birds and marine mammals.

onnes

300

For example the distribution of a fi sh species is limited not only by

1 000 t

200

the temperatures at which the species can survive, but especially by

100

the narrow temperature interval in which reproduction is successful.

Accordingly, the geographical range of Greenlandic fi sh species is

0

primarily determined by the distribution of cold water of polar origin

1960

1964

1968

1972

1976

1980

1984

1988

1992

1996

2000

and warmer water of Atlantic origin.

Year

160

Southwest and southeast Greenland

With respect to commercial fi sheries resources, the marine ecosystems

140

Other fish and shellfish

Northern shrimp

of Southwest and Southeast Greenland waters are the most productive

120

Greenland halibut

Redfish

in Greenland and the best investigated ones. They are intermediate

Atlantic cod

100

between the cold polar water masses of the Arctic region and

onnes

80

the temperate water masses of the Atlantic Ocean and they are

1 000 t

60

characterised by relatively few dominant species (e.g. Jensen, 1939;

Hansen, 1949; Rätz, 1999; Pedersen and Zeller, 2001). Ocean currents

40

that transport water from the polar and temperate regions aff ect the

20

marine productivity in the Greenland shelf areas, and changes in the

0

North Atlantic circulation system therefore have major impact on the

1960

1964

1968

1972

1976

1980

1984

1988

1992

1996

2000

distribution of species and fi sheries yield (Rätz, 1999; Rätz et al., 1999

Year

Pedersen and Rice, 2002; Pedersen et al., 2002, 2003; Wieland and

Figure 6

Catches of fi sh from region 16, West Greenland

Shelf (upper fi gure) and region 15, East Greenland

Hovgaard, 2002; Buch et al., 2004). The relative strengths of the warm

(lower fi gure).

vs. cold water currents contribute to the defi nition of the habitat of the

(Data from Horsted, 2000; NAFO, 2003; ICES, 2003; and Greenland Institute of

Natural Resources. Data for catches of fish in "LME: East Greenland" other than

fl ora and fauna.

cod is lacking before 1969)

Fish

the present very low levels (Rätz, 1999; Buch et al., 2004). During the

Since the beginning of the 20th century, cod (Gadus morhua) has been

same period, however, catches (inshore and off shore combined)

the most important commercial fi sh species in Greenland waters, with

of two other important species, Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius

annual catches peaking at levels between 400 000 and 500 000 tonnes

hippoglossoides) and northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) increased and

in the 1960s (Mattox, 1973; Horsted, 2000). Until the introduction of the

annual catches are presently about 25 000 tonnes and 100 000 tonnes,

200 mile EEZ in 1977, most of the catch was taken by foreign vessels.

respectively.

During the late 1960s, the annual catches of cod and other commercially

important fi sh species - mainly taken as by-catch in the cod fi shery, e.g.,

Other living resources

redfi sh (Sebastes marinus), Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus)

In addition to the fi sheries yields from mainly the West Greenland,

and wolffi

sh (Atlantic wolffi

sh, Anarhichas lupus, and spotted wolffi

sh,

but also the East Greenland large marine ecosystem, one has to add

A. minor) declined drastically (Figure 6).

the hunting (and consumption) of more than 100 000 seals, several

hundred whales and several hundred-thousand seabirds per year

After 1970 the catches of cod and redfi sh showed fl uctuations at much

on average (e.g. Mosbeck et al., 1998; Greenland Institute of Natural

lower levels compared to the 1960s (Figure 6). Except for a temporary

Resources, 2000; Namminersornerullutik Oqartussat, 2002). The seal

improvement of the cod fi shery during 1988-1990, the catches of cod,

hunt targets primarily ringed seals (Phoca hispida) and harp seals (Phoca

redfi sh, Atlantic halibut and wolffi

sh showed decreasing trends towards

groenlandica), but also other species including the walrus (Odobenus

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

rosmarus). The whale hunt is mainly on fi n whales (Balaenoptera

sustainable development issues. They have also included three more

physalus), minke whale (B. acutorostrata), beluga (Delphinapterus

indigenous organisations for a total of six permanent participants. One

leucas), narwhal (Monodon monocerus) and occasionally others. The

of the programs created under the Arctic Environmental Protection

seabird hunt is primarily on Brünnich's guillemot / thick-billed murre

Strategy and continued under the Arctic Council is the Arctic

(Uria lomvia), king eider (Somateria spectabilis), common eider (S.

Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). AMAP was designed

mollissima), little auk (Alle alle) and kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla). Polar bear

to address environmental contaminants and related topics, such as

(Ursus maritimus) is hunted and a total of about 170 animals are killed in

climate change and ozone depletion, including their impacts on human

Greenland per year with approximately an equal number in West- and

health (AMAP, 2002). In 2000, the Arctic Council approved the Arctic

East Greenland (Namminersornerullutik Oqartussat, 2002).

Climate Impact Assessment, overseen by AMAP, its sister working group

on Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), and the International

Transboundary aspects

Arctic Science Committee. According to AMAP (2002), this impact

The marine animal resources, e.g. fi sh, sea birds and sea mammals,

assessment will deliver a report to the Arctic Council in 2004.

generally have an extensive distribution area, involving the waters of

several nations. This means that fi shery, hunting and other infl uences

Greenland has responded to threats to the freshwater systems and

on one part of a population will eventually aff ect the rest of it, within

the fauna and fl ora these habitats support by establishing protected

as well as outside of Greenland waters. International cooperation

areas and designating important wetland areas under the Convention

on management and protection of marine species and resources is

on Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar) (Figure 7; Egevang

thus imperative if sustainable yields and protections of endangered

and Boertmann, 2001).

species are to be attained. Accordingly, Greenland is member of several

international organisations that advise a sustainable use of Greenland's

The objective of the UNESCO Convention concerning World Heritage

marine resources, e.g. North Atlantic Fisheries Organisation (NAFO),

is to help protecting irreplaceable expressions of former cultures and

International Council for the Explorations of the Sea (ICES), North

of natural landscapes of great importance and beauty. The foundations

East Atlantic Fishery Commission (NEAFC), North Atlantic Salmon

for two international conventions were laid in the mid-1960s and later,

Conservation Organisation (NASCO), Joint Commission for the

Conservation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga (JCNB), North

Atlantic Marine Mammal Conservation Organisation (NAMMCO), and

International Whaling Commission (IWC).

Thule

Greenland's membership of e.g. ICES and IWC is through Denmark

North and Northeast Greenland

National Park

and Greenland has an active Greenlandic representation/participation.

Greenland is a self-governing part of the Kingdom of Denmark. In

Melville Bay

1979 the Home Rule Act transferred the mandate of legislation to

the Greenland Parliament in all areas defi ned to be issues of self-

government. Hence, regulations issued in Denmark or international

conventions ratifi ed by her are not automatically in force also in

Lyngmarken

Greenland.

Qeqertarsuaq

Ilulissat Icefjord

Arnangarup Qoorua

In 1991, the eight Arctic countries Canada, Denmark, Finland,

(Paradisdalen)

Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, and the United States initiated the

Nuuk

Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy. Under this framework, the

Akilia

countries pledged to work together on issues of common concern.

Recognising the importance of the environment to the indigenous

Ikka

communities of the Arctic, the countries at that time included three

0

500 Kilometres

© GIWA 2004

Qinguadalen

indigenous organisations in their cooperative programs. In 1996, the

Figure 7

National parks and protected areas indicated by their

eight Arctic countries created the Arctic Council, incorporating the

name.

Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy and expanding it to include

(Greenland Home Rule, 2004).

REGIONAL DEFINTION

19

in 1972, merged into one, the UNESCO World Heritage Convention. The

Kingdom of Denmark, some fi elds of responsibility remain under the

fi ve Nordic countries, among others, ratifi ed the convention between

Danish state, including the Constitution, the right to vote, eligibility for

1977 and 1995. As Greenland is not a sovereign state, in these matters

election of justice, the concept of citizenship, inspection and enforcing

Greenlandic interests are upheld through the Danish government.

of jurisdiction in territorial waters, as well as all foreign policy and

monetary aff airs.

After a request by the Danish Ministry of the Environment in 1988,

the Greenland government has selected natural heritage areas and

The Home Rule Government is responsible for all other administrative

cultural monuments in Greenland for inclusion in the UNESCO World

areas, including transport and communication, and the environment

Heritage List (Mikkelsen and Ingerslev, 2002). This work was properly

and nature. The rights to Mineral and Petroleum are shared between

organised in 1995 when cooperation was established between the

the Danish Government and the Greenland Home Rule. Greenland is

Greenland Department of Culture, Education and Ecclesiastical Aff airs,

not a member of the EU, but has an OCT scheme (Overseas Countries

the Department of Health, Environment and Research, the Greenland

and Territories) that ensures the country open access to the European

National Museum and Archives, and the Greenland Institute of Natural

market for its fi sh products.

Resources. The Greenland National Museum selected culturally

signifi cant historical objects and the Institute of Natural Resources

Population

pointed out areas of special interest for the natural environment.

The population of Greenland was 56 542 in 2002 of which ~88%

Subsequently, these proposals comprised sites of both natural and

were born in Greenland, which is the offi

cial proxy measure for

cultural history.

Greenlandic (Inuit) ethnicity (Anon, 2003b). Most of the remainder of

the population (~12%) comes from Denmark. The population pyramid

The icefj ord of Ilulissat/Jakobshavn, West Greenland, which covers

for the indigenous population is relatively broad based until the age

an area of 796 km2 are being evaluated to become the fi rst UNESCO

group 30-34. Around 1970, a very high fertility rates decreased rapidly

World Heritage area in the Arctic (Mikkelsen and Ingerslev, 2002).

which, in combination with relatively few women of childbearing age,

The result of this evaluation will be announced in 2004. The icefj ord

resulted in small birth cohorts (Figure 8). After the dramatic decrease,

contains the Jakobshavn Glacier, which is a fl oating, calving ice cap

the size of the birth cohorts increased steadily from 1974 to 1995 but is

glacier. The glacier is presently located about 40 km east of the town

now once more on the decrease (Bjerregaard, 2003).

of Ilulissat. Because of the relatively easy access to the glacier from the

settlements in the immediate vicinity, the fj ord and glacier are well

known. The glacier is particularly famous for its high speed of 1 m/h

Age

Males

Females

and its production of calving ice which amounts to about 30 km3/year.

80+

This is more than any other glacier and comprises about 10% of the

75-79

entire production of calving ice from the Greenland ice cap (Mikkelsen

70-74

and Ingerslev, 2002).

65-69

60-64

55-59

50-54

Socio-economic characteristics

45-49

40-44

35-39

Political structure

30-34

Greenland has been a colony of Denmark since 1728, and obtained

25-29

20-24

home rule in 1979, so it is at present a semi-independent province of

15-19

Denmark. The Home Rule Government consists of a directly elected

10-14

parliament (the Landsting), comprising 31 members. A general

5-9

election is held every four years. The Landsting elects a government

0-4

(the Landsstyre), which is responsible for the central administration

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

%

under the Prime Minister (the Landsstyreformand). The members of

Figure 8

Population pyramid for Greenland, 2001.

the government head the various ministries. As Greenland is part of the

(Source: Greenland Statistics; AMAP, 2003)

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

East Greenland is inhabited by only about 3 600 people. West

Lifestyle

Greenland is inhabited by the majority of the Greenland population,

A sedentary lifestyle is becoming increasingly common among the

about 53 000 people, and the Greenland fi shing industry and all major

Greenlanders. In the villages, only 7% are self-reported sedentary

cities including the Capital Nuuk are situated in West Greenland. In

while this increased to 23% among the well-educated residents of

the capital, Nuuk, lives 13 500 people. 80% of the population lives in

the capital, Nuuk. Overweight is an increasing problem among the

coastal towns and settlements in Southwest Greenland and the Disko

Greenlanders; 35% and 33% of men and women, respectively, are

Bay, where also most of the commercial fi shing takes place and the fi sh

overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9) and 16% and 22% are obese (BMI=> 30)

processing plants are located. Outside this area subsistence hunting and

(Bjerregaard, 2003).

fi shing are predominant occupations. The fi shery in East Greenland is

performed by off shore fi shing vessels, both Greenlandic and foreign

The consumption of alcohol and tobacco has increased considerably

vessels, whereas the local and coastal fi shery is small, but of cultural

during the last 30-40 years but is now stagnant (Bjerregaard, 2003). The

and sociological importance.

impact of alcohol on social and family life is marked. Among those born

after 1960, more than 50% state that they experienced alcohol related

Culture

problems in their parental home.

The Danish/Norwegian colonisation of West Greenland started in

1721, and what today is termed the traditional Greenlandic culture is

According to import statistics, the average consumption of cigarettes

a mixture of Inuit and European culture. The traditional occupation of

increased from 5 cigarettes per day in 1955-59 to 9 in 1990-94. Recent

the Greenlanders until the early 20th century was the hunting of marine

population surveys estimate the proportion of cigarette smokers to be

mammals (seal, whales, and walrus). During the 20th century hunting

70-80% among both men and women compared with 40% in Denmark,

was increasingly substituted by fi shing, fi rst from small dinghies but later

but the proportions of heavy smokers are similar in the two countries.

from large sea-going vessels using the most modern equipment. The

Young people start smoking very early, often well before the age of 15,

Greenlandic culture today is still very much centred around traditional

and the lowest smoking prevalence is found among the elderly.

Greenlandic food (kalaalimernit), which is understood as the meat and

organs of marine mammals and fi sh often eaten raw, frozen or dried.

Economy

Seal meat, for instance, is usually ascribed several positive physical as

In 1998 gross national income (GNP) was more than 7.5 billion Dkr,

well as cultural qualities, and asking a person whether he or she likes

corresponding to 134 000 Dkr per capita. (Dkr = Danish Crowns; 1 Euro

seal meat is equivalent to asking whether he or she considers himself/

equals approximately 7.4 Dkr) (Anon., 2003b). Principal income for the

herself to be a true Greenlander (Bjerregaard, 2003).

Home Rule Government comes from a block grant from the Danish

state, which constitutes about 2/3 of the Greenland economy. The

Traditional sealing and whaling still plays an important role in the life of

remaining 1/3 is overwhelmingly based on fi shery and its products.

people especially in Northwest, North, and East Greenland although it

In addition, the Home Rule Government and the municipalities have

is not the dominant industry in economic terms. Leisure time hunting

revenue from personal and corporate taxes, indirect taxes, and licences.

and fi shing is a very common activity.

In addition, Greenland receives payment from the EU for access by EU

fi shermen to Greenland's fi shing waters.

The consumption of marine mammals, fi sh and sea birds is high, but

the young and the population in towns eat considerably less than

Exports

the elderly and the population in the villages. Seal is the most often

In 2001, 87% of Greenland's exports of 2 251 million Dkr consisted of fi sh

consumed traditional food item followed by fi sh. On average, 20% of

products, 60% of which were shrimps (Anon., 2003b). The export value

the Greenlanders eat seal 4 times a week or more often while 17% eat

of fi sh products is heavily dependent on the prices on the world market.

fi sh similarly often. Traditional food is valued higher than imported

Although there was a considerably larger production of shrimps in 2001

food; the highest preference is given to mattak (whale skin), dried

than ever, falling prices on the world market considerably reduced the

cod, guillemot, and blackberries. Almost all value traditional food as

export value.

important for health and less than one percent (in 1993-94) restricted

their consumption of marine mammals or fi sh because of fear of

Imports

contaminants (Bjerregaard, 2003).

Apart from fi sh and hunting products, only few goods are produced

in Greenland. Imports therefore include almost all goods used in

REGIONAL DEFINTION

21

households, business and institutions. In 2001 imports amounted to

Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides) on the other hand, has

2 466 million Dkr.

in the last 2 decades become important to the economy of the country.

The yearly catch of more than 20 000 tonnes comes fi rst and foremost

Industry

from the northwesterly districts.

Fishing is the main industry, and it is estimated that about 2 500 people

are directly employed by it. In addition, around 3 000 people work in

Redfi sh, catfi sh, Atlantic halibut, salmon and char are of minor

the fi sheries industry and derivative occupations. Hunting is of direct or

economical importance, however, important to the local socio-

indirect signifi cance for about twenty percent of the population, and is

economy in towns of Southwest Greenland.

the principal occupation Northern and Eastern Greenland. Sheep and

reindeer are raised in South Greenland. For many years it was expected

A number of marine mammals are essential for the survival of the

that tourism and the extraction of raw materials eventually would

traditional hunting communities. The most important of these are the

become leading industries, supplementing fi shing as major sources of

fi ve species of seal which are found in the waters around Greenland.

income. So far, however, the expectations have not been met.

The most common is the ringed seal, and the Greenlanders still harvest

around 80 000 of these every year whereas they also harvest 80 000 of

The fi sheries in Greenland are characterised by three main sectors

all the other species put together. A number of walruses and whales

with distinct diff erences between large-scale off shore, intermediate

are also caught (see Assessment, Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and

and small-scale inshore activities. This is not only due to structural and

other living resources). Considerable sums are involved in the lively

economic patterns, but also caused by political relations of importance

trade in meat which is only used locally. The only commercial use of

for the development process. The large-scale sector is dominated by a

the seals comes from the sale of skins to the Great Greenland tannery in

capital rationale, with concentration and centralisation through large-

Qaqortoq (Julianehåb). The Home Rule Government provides generous

scale projects and economy of scale as the fundamental mechanisms,

subsidies to the sealers because of the diffi

culty in selling the skins on

giving access to resources otherwise inaccessible, and the major

the world market. Polar bear hunting and the sale of polar bear skin are

contributor to the national economy. The intermediate sector of the

socio-economical important locally in West and East Greenland.

regional fi sheries is partly based on capital rationality, partly on a life

form which has become a backbone of many of the larger settlements,

The rich bird life around the coasts has also played a role in the life of

but also present in many smaller settlements. This sector is important

the Greenlanders. In addition to a number of diff erent types of gulls and

for the regional economies. The small-scale sector, relying on small

ducks, of which the most important is the common eider, uses have also

boats, dog-sledges and skidoos, is vital for the small settlements, and

been found for a number of colony birds, not least Brünnich's guillemot,

consequently constituting the backbone of the cultural heritage, and

known commonly as the polar guillemot.

important for the direct and indirect political attempts to maintain

reasonable living conditions for the smaller places. At the same time its

The fi shing and marine mammal hunting in Greenland is founded

contribution to the maintenance of the informal and subsistence sector

on resource assessments and quotas given by international advisory

is certainly not negligible (Rasmussen, 1998c; Caulfi eld, 1997; Marquardt

organisations and committees on fi shery and marine mammal

and Caulfi eld, 1995).

management (NAFO, ICES, NASCO, NEAFC, JCCM, NAMMCO, and IWC)

of which Greenland is a member. The Greenland Institute of Natural

Fishing and hunting

Resources is responsible for providing scientifi c advice on the level

Northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) constitute the most important

of sustainable exploitation of the living resource to the Greenland

commercial export. The annual catches of around 100 000 tonnes

Government, including long-term protection of the environment

contribute more than 1 billion Dkr to the Greenland economy. However,

and biodiversity. As of today, the scientifi c advice to the Greenland

this contribution is depending on e.g. the world marked prize for shrimp

Government of sustainable use of the renewable resources is entirely

products.

based on single-species assessments given for one year. However, for

northern shrimp (the most important commercial fi shery) an analytical

Cod (Gadus morhua) previously played a central role in the development

assessment framework using a stochastic version of a surplus-

of the economy, but the cod landings have fallen to <2 000 tonnes and

production model that included an explicit term for predation by cod

cod fi shing in Greenland today is of very low economic importance

was applied for the fi rst time in 2002.

compared to former periods.

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

Today cooperation between Greenland and EU is dominated by

Conclusion

fi sheries agreements. Within these agreements EU pays Greenland for

rights to fi sh parts of the quotas of the Greenland fi sh stocks. However,

The GIWA regions of Greenland, Arctic (1), East Greenland Shelf (15),

from 2007 Greenland and EU are expected to make a wider partnership

and West Greenland Shelf (16), cover huge areas, but they are sparsely

agreement.

populated. The development of modern Greenland has been based

on fi shing and hunting natural resources. Besides the importance of

The Greenland Government regulates the utilisation of renewable

transfers from Denmark, the society of Greenland, including the local

resources by quotas, license's and technical measures (e.g. mesh

economies, depends on living resources from the sea, and more than

sizes or closed seasons) (Namminersornerullutik Oqartussat, 2002;

90% and Greenland's total export value stems from fi sh products.

www.nanoq.gl). To enforce the decided regulations and laws on

Likewise, the social and physical health of Greenlanders, notably those

fi shing and hunting, Greenland has established the "Greenland

living in the more isolated areas, depends to a high degree on the

Fishing License Control" (GFLK) and "Greenland Hunting Patrol"

collection and consumption of traditional food.

(Jagtbetjentordningen).

Farming and land use

Geographically, Greenland's agriculture is placed in the south. It consists

mainly of sheep farming, and 25 000-30 000 lambs are produced each

year. There are also two farms with domesticated reindeer. The number

of sheep has remained relatively stable since 1990, whereas the number

of domesticated reindeer has more than halved. The area farmed has

increased by 85% since 1990 due to cultivation of heath lands for hay

cutting.

There is no forestry in Greenland apart from four experimental

plantations with conifers, with a total area of 100 ha.

In Greenland there are no roads connecting towns. Therefore all traffi

c

between towns and settlements is either by ship, boat, dog-sledge

(seasonally), snowscooter (seasonally) or by fi xed-wing aircraft or

helicopter. In the towns most goods are transported by car. The main

gateways to Greenland are the international airports (former American

military bases) in Narsarsuaq (South Greenland) and Kangerlussuaq

(West Greenland). From here traffi

c to all Greenland destinations is

being distributed either by small airplanes or by helicopters. The two

towns in East Greenland are accessible by air from Iceland.

Almost all goods transport, both to and within Greenland, is by sea.

A small proportion, mainly mail and perishable goods, is transported

by air. Only the areas from Paamiut (Frederikshåb) to Sisimiut

(Holsteinsborg) on the west coast is open water all year round, and

therefore accessible by boat. South of Paamiut (Frederikshåb) drift ice

from the east coast can cause trouble for fi sheries and transportation in

the summer months. North of Sisimiut (Holsteinsborg), ice conditions

limit navigation during winter. On the east coast ice may cause troubles

year round, as the east coast can only be navigated for a few months

in the summer.

REGIONAL DEFINTION

23

Assessment

This section presents the results of the assessment of the impacts of each of the fi ve predefi ned GIWA concerns i.e. Freshwater shortage,

Pollution, Habitat and community modifi cation, Overexploitation of fi sh and other living resources, Global change, and their constituent

issues and the priorities identifi ed during this process. The evaluation of severity of each issue adheres to a set of predefi ned criteria

as provided in the chapter describing the GIWA methodology. In this section, the scoring of GIWA concerns and issues is presented in

Table 1.

Table 1

Scoring tables for the Arctic Greenland, East Greenland and West Greenland regions.

Arctic Greenland

East Greenland

West Greenland

y

y

y

a

l

a

c

t

s

a

c

t

s

a

c

t

s

p

*

*

a

l

p

*

*

a

l

p

*

*

a

c

t

s

a

c

t

s

a

c

t

s

ent

p

ent

p

ent

p

m

i

c

i

m

m

i

c

i

m

m

i

c

i

m

n

i

m

Score

n

i

m

Score

n

i

m

Score

c

t

s

m

m

m

o

communit

c

t

s

communit

communit

r

i

t

y

*

*

*

c

t

s

o

c

t

s

r

i

t

y

*

*

*

c

t

s

o

c

t

s

r

i

t

y

*

*

*

v

i

r

o

n

n

n

o

a

l

t

h

a

l

t

h

a

l

t

h

t

her

erall

io

v

i

r

o

o

t

her

erall

io

v

i

r

o

o

t

her

erall

io

En

impa

Ec

He

O

impa

Ov

Pr

En

impa

Ec

He

O

impa

Ov

Pr

En

impa

Ec

He

O

impa

Ov

Pr

Freshwater shortage

0*

0

0

0

0

4

0*

0

0

0

0

5

0*

+1

0

0

0

5

Modification of stream flow

0

0

1

Pollution of existing supplies

0

0

1

Changes in the water table

0

0

0

Pollution

2*

0

0

0

2

3

3*

0

3

3

3

1

2*

0

3

0

2

2

Microbiological pollution

0

0

0

Eutrophication

0

0

0

Chemical

2

3

2

Suspended solids

0

0

0

Solid waste

0

0

1

Thermal 0

0

0

Radionuclide

0

0

0

Spills

0

0

0

Habitat and community modification

0*

0

0

0

0

2

1*

0

1

0

1

3

2*

0

0

0

2

3

Loss of ecosystems

0

0

0

Modification of ecosystems

0

1

2

Unsustainable exploitation of fish

0*

0

0

0

0

5

*3

0

2

0

3

2

3*

0

0

0

3

1

Overexploitation

0

3

3

Excessive by-catch and discards

0

1

1

Destructive fishing practices

0

3

3

Decreased viability of stock

0

0

0

Impact on biological and genetic diversity

0

0

0

Global change

2*

0

0

0

2

1

1*

0

0

0

1

4

1*

0

0

0

1

4

Changes in hydrological cycle

2

1

1

Sea level change

0

0

0

Increased UV-B radiation

1

1

1

Changes in ocean CO source/sink function

1

1

1

2

Assessment of GIWA concerns and issues according to scoring criteria (see Methodology chapter)

The arrow indicates the likely direction of future changes.

T

T

T

T

C

C

C

C

A

A

A

A

Increased impact

No changes

Decreased impact

0 No

known

impacts

1 Slight

impacts

2 Moderate

impacts

3 Severe

impacts

IMP

IMP

IMP

IMP

* This value represents an average weighted score of the environmental issues associated to the concern. ** This value represents the overall score including environmental, socio-

economic and likely future impacts. *** Priority refers to the ranking of GIWA concerns.

24

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 1B, 15, 16 ARCTIC GREENLAND, EAST GREENLAND SHELF, WEST GREENLAND SHELF

Freshwater shortage

Socio-economic impacts

Economic impacts

The Greenland ice cap contains nine percent of the world's freshwater.

West Greenland (region 16) a hydro power plant outside the Capital of

Greenland's water is renowned as some of the fi nest in the world. The

Greenland, Nuuk, has been positive for the economic development.

purity of the water has been measured at various locations in Greenland

in order, so to speak, to set the instruments used for measuring pollution

Health impacts

at zero (Pedersen, 2002).

No known impact.

Environmental impacts

Other social and community impacts

Modifi cation of stream fl ow