Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessments

Other reports in this series:

Russian Arctic GIWA Regional assessment 1a

Caribbean Sea/Small Islands GIWA Regional assessment 3a

Caribbean Islands GIWA Regional assessment 4

Barents Sea GIWA Regional assessment 11

Baltic Sea GIWA Regional assessment 17

Caspian Sea GIWA Regional assessment 23

Gulf of California/Colorado River Basin GIWA Regional assessment 27

Yellow Sea GIWA Regional assessment 34

East China Sea GIWA Regional assessment 36

Patagonian Shelf GIWA Regional assessment 38

Brazil Current GIWA Regional assessment 39

Amazon Basin GIWA Regional assessment 40b

Canary Current GIWA Regional assessment 41

Guinea Current GIWA Regional assessment 42

Lake Chad Basin GIWA Regional assessment 43

Benguela Current GIWA Regional assessment 44

Indian Ocean Islands GIWA Regional assessment 45b

East African Rift Valley Lakes GIWA Regional assessment 47

South China Sea GIWA Regional assessment 54

Sulu-Celebes (Sulawesi) Sea GIWA Regional assessment 56

Indonesian Seas GIWA Regional assessment 57

Pacifi c Islands GIWA Regional assessment 62

Global International

Waters Assessment

Regional assessment 24

Aral Sea

GIWA report production

Series editor: Ulla Li Zweifel

Editorial assistance: Matthew Fortnam, Monique Stolte

Maps & GIS: Rasmus Göransson

Design & graphics: Joakim Palmqvist

Global International Waters Assessment

Aral Sea, GIWA Regional assessment 24

Published by the University of Kalmar on behalf of

United Nations Environment Programme

© 2005 United Nations Environment Programme

ISSN 1651-940X

University of Kalmar

SE-391 82 Kalmar

Sweden

United Nations Environment Programme

PO Box 30552,

Nairobi, Kenya

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and

in any form for educational or non-profi t purposes without

special permission from the copyright holder, provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this

publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the

United Nations Environment Programme.

CITATIONS

When citing this report, please use:

UNEP, 2005. Severskiy, I., Chervanyov, I., Ponomarenko, Y.,

Novikova, N.M., Miagkov, S.V., Rautalahti, E. and D. Daler. Aral

Sea, GIWA Regional assessment 24. University of Kalmar, Kalmar,

Sweden.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors

and do not necessarily refl ect those of UNEP. The designations

employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions

of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or cooperating

agencies concerning the legal status of any country, territory,

city or areas or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has been peer-reviewed and the information

herein is believed to be reliable, but the publisher does not

warrant its completeness or accuracy.

Printed and bound in Kalmar, Sweden, by Sunds Tryck Öland AB.

Contents

Preface 9

Executive summary

11

Acknowledgements 14

Abbreviations and acronyms

15

Regional defi nition

17

Boundaries of the region

17

Physical characteristics

18

Socio-economic characteristics

22

Assessment 29

Freshwater shortage

29

Pollution

34

Habitat and community modifi cation

39

Unsustainable exploitation of fi sh and other living resources

43

Global change

43

Priority concerns for further analysis

47

Causal chain analysis

48

Introduction

48

Causal chain analysis

48

Conclusions

55

Policy options

56

Defi nition of the problem

56

Policy options

57

Recommended policy options

57

Conclusion

59

Conclusions and recommendations

60

References 62

Annexes 67

Annex I List of contributing authors and organisations

67

Annex II Detailed scoring tables

68

Annex III List of important water-related projects

71

The Global International Waters Assessment

i

The GIWA methodology

vii

CONTENTS

Preface

Water has always been the most limiting factor for the inhabitants

limited progress realised. In fact, a sardonic proverb concludes that, "If

of Central Asia. Historically, the countries of the region have adapted

all visiting experts had brought a bowl of water with them the Aral Sea

to the water scarce conditions through a legacy of sustainable water

would have been fi lled up again."

management that dates back several thousand years.

With the present global agenda set on achieving sustainable

The Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA) of the Aral Sea Basin

development and eradicating poverty, the countries of Central Asia

describes how since the 1960s water abstraction for economic activities,

must foremost address the root causes of its water problems. The

particularly irrigated farming, has become unsustainable and now

UN International Decade for Action 20052015, Water for Life, was

exceeds the carrying capacity of the region's ecosystems. Insuffi

cient

launched by the President of Tajikistan who also raised international

water is allocated to the lower reaches of the region's rivers and the

awareness of the water crisis in Central Asia. In the forthcoming years

Aral Sea, which has resulted in an environmental catastrophe. The

water polices, aimed at achieving the Millennium Development Goals,

inhabitants of the region are now forced to survive under conditions

will be implemented in all the countries of the region.

of increasing water stress. Against this backdrop, poverty and poor

health are rife throughout the region, from the Tajik mountains to the

In this context the GIWA assessment serves as a useful tool for decision

waterlogged wetlands of Karakalpakstan.

makers when exploring new mechanisms to resolve the situation.

Complementary to the GIWA assessment, the Global Water Partnership

The assessment takes a holistic approach to analysing the transboundary

(GWP) provides a neutral forum for regional stakeholders to discuss

environmental concerns of the region and in identifying the root causes

relevant water issues and formulate solutions through sustainable and

behind these problems. Specialists of various environmental and socio-

equitable water management practices.

economic disciplines expressed the immanency of the situation and

the need to take urgent action. Recent progress in addressing water

During the GWP Central Asia and Caucasus stakeholder conference

management issues is also discussed in the report and various options

in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, in January 2005, the outcomes of the GIWA

are proposed to reverse the negative trends in the condition of the

assessment were presented and discussed by participants. While the

aquatic environment of the Aral Sea Basin.

global community may assist in catalysing change, restructuring the

water agenda of Central Asia into a sustainable framework must be

Donors for over a decade have funded various initiatives aimed at

undertaken by regional policymakers.

resolving the causes of freshwater shortage in the region, but with

Björn Guterstam

Network Offi

cer

Global Water Partnership Secretariat, Stockholm

PREFACE

9

Executive summary

The Aral Sea Basin (GIWA region 24) is located in Central Asia and entirely

In view of this situation the concern of freshwater shortage, and more

or partially, covers Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan,

specifi cally the issue of stream fl ow modifi cation, was prioritised for

Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Iran. The transboundary waters of

Causal chain analysis (CCA) and Policy options analysis (POA). The GIWA

the region are the Syrdarya and Amudarya rivers, which have a major

Task Team identifi ed the following as immediate causes of modifi cation

hydrological impact on the Aral Sea Basin.

of stream fl ow:

Increased

diversion;

The GIWA Assessment evaluates the current status and the historical

Decreased ice resources;

trends of each of the fi ve predefi ned GIWA concerns i.e. freshwater

Inter-annual

climatic

variability.

shortage, pollution, habitat and community modifi cation, unsustainable

exploitation of fi sh and other living resources, global change, and

The main root causes of increased diversion stem from the regulation

their constituent issues. The assessment determined that freshwater

of rivers by reservoirs, which store huge volumes of water for irrigation

shortage exerted the greatest impacts on the Aral Sea Basin. The eff ect

and power generation. The collapse of the USSR triggered further

of climate change on freshwater shortage has also been considered in

problems for the region. The previously integrated economic system

this report.

fragmented, and social and economic turmoil followed, e.g. civil war

in Tajikistan (1992-1997). The quotas from the Soviet era have been

Freshwater shortage is a fundamental problem for the countries of

maintained and they regulate water use to some degree. However, in

Central Asia which has led to the destruction of ecosystems in the

recent years Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have persistently disputed the

Aral Sea and the degradation of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems in

current system of quotas and demand that they be revised. There is

Priaralye. As a result of freshwater shortages, the reuse of return waters

insuffi

cient coordination between upstream and downstream states

in irrigated farming is becoming more frequent, resulting in heavy

regarding the allocation of water resources and a lack of mechanisms

soil salinisation and the pollution of surface and underground waters.

aimed at regulating the diversion of rivers. Confl icts between the

Consequently, poor quality drinking water is having severe health

various water users, particularly hydropower engineering and irrigation,

impacts on the population, particularly in Priaralye.

remain unresolved.

In the 1960s when the total population in fi ve countries in the region

The following were identifi ed as root causes of freshwater shortage in

(excluding Afghanistan and Iran) was approximately 15 million, more

the region:

than 50% of the annual water yield of the Syrdarya and Amudarya

rivers was used for economic purposes. Since the beginning of the

Demographic: Increases in population have led to greater pressure on

1980s the renewable water resources of the Syrdarya and Amudarya

the water resources of the Aral Sea Basin.

basins are fully exploited and the regional economy is developing under

conditions of increasingly severe water shortages.

Economic: The collapse of the economic system formed under

Soviet rule, has led to a recession in the region and social upheavals.

Consequently, investment in the agricultural sector reduced, which led

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

to a decline in the productivity and the water effi

ciency of irrigation

The current use of transboundary water resources in Central Asia

systems. Water users are not given economic incentives to conserve

is complex due to a range of demographic, socio-economic and

water resources and there is no common approach to economically

ecological trends. In the post-Soviet period essential diff erences have

evaluating water.

been revealed concerning the approaches used by the countries within

the region to the mutual use of regional water resources, especially

Legal: There is weak legislation regulating water management. A

regarding the principles and criteria of interstate water sharing and

mutually acceptable legislative framework for interstate sharing of

the legal and economic mechanisms of water use. In addition to

transboundary water resources is absent. The current water legislation

the economic problems encountered during the transitional period

was formulated during the Soviet period and is not appropriate under

from Soviet rule, coordination between the countries in the sharing

present-day conditions.

of transboundary water resources and nature protection has also

proved problematic. Despite eff orts by the region's governments and

Governance: The transboundary nature of the major watershed basins in

the international community, the situation of water supply in Central

the region makes it impossible to solve the freshwater shortage concern

Asian states remains critical. One of the main reasons for the lack of

without inter-state agreements. Many of the agreements made to date

progress is the tendency of governments to take unilateral decisions

have not been implemented or adhered to by the countries of the

and actions, which often exacerbate problems in other countries due

region. For example, despite the governments signing agreements

to the transboundary nature of water resources.

aimed at resolving the water management issues, all of the countries

in the region intend to increase their irrigated areas. The transboundary

A signifi cant reduction in the volume of water resources used in human

water management system is inadequate as it is based on the principles

activities is unlikely in the region, at least in the immediate future.

of centralised regulation formed in the Soviet period. There is a lack

However, water management in the forthcoming decades can be

of clearly formulated national water strategies and each country's is

based upon the modern volume of available water resources, as there

signifi cantly diff erent, adopting various approaches to addressing the

is not believed to be signifi cant reductions in freshwater availability

problems of interstate use of water resources of transboundary basins

as a result of climate changes. Despite the considerable reduction

management. The national strategies are not integrated at the regional

in glacial resources, the fl ow rates of the main rivers have remained

level, for example, through a regional water strategy.

relatively unaltered in recent decades, suggesting the existence of a

compensating mechanism. It is believed that an infl ow of freshwater

Knowledge: The lack of knowledge regarding the contemporary

from the melt-water of underground ice accumulates in the perennial

characteristics of the region's water resources and future climatically

permafrost. The area of perennial permafrost is many times greater

induced changes in freshwater availability, is severely hindering

than the area of present-day glaciers, and therefore even slight melting

policy makers in making informed decisions in order to resolve water

of the permafrost could compensate for the reduction in freshwater

management issues.

supply caused by the decline in the area of the glaciers. This has yet

to be adequately researched by the scientifi c community, despite its

Technology: Water resources are not being utilised effi

ciently due to

importance when considering the infl uence of climate changes on

irrigated agriculture employing outmoded technology. Economic

freshwater resources.

constraints and the lack of economic incentives for farmers to save

water, is preventing the adoption of water saving technologies.

Increased water abstraction may lead to an ecological disaster by the

year 2010. The situation is so critical that this scenario may transpire if

Climatic variability: Freshwater shortage may become even more acute

only one of the countries increases abstraction of surface waters. The

over the next few decades if as predicted, water resources in the region's

success of interstate agreements on the sharing of water resources

major river basins reduce by 20-40%. However, some predictions show

may be jeopardised by the current level of water use, the continued

anthropogenic induced climate change to play a less signifi cant role

deterioration of water infrastructure and degradation of the environment.

than was previously thought as there is evidence of a compensating

A prerequisite to resolving the freshwater shortage problem is a

mechanism in the formation of run-off which is maintaining the total

comprehensive knowledge of the hydrodynamics of the region.

volume of renewable water resources.

12

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 24 ARAL SEA

The report highlights policy options which governments could

Financial, technical and organisational support is required from

implement and incorporate into strategic policies. The main

international organisations in the:

recommendations are:

reconstruction and updating of irrigation systems to increase water

The development and enactment of national water strategies

effi

ciency;

that comply with international water law and take into account

development of legislative principles and mechanisms for water

the interests of all the countries in the region. They should aim to

use at all levels, and in the implementation of integrated water

increase the effi

ciency of water use, primarily in irrigated farming,

resources management principles, and,

and promote the conversion of water intensive crops, such as rice

monitoring of the environment, particularly regarding climatically

and cotton, to less water intensive crops.

driven glaciosphere dynamics in the zone of run-off formation,

To broaden the understanding of socio-economic and

where approximately 75% of the region's renewable water

environmental characteristics and their relationship with the water

resources orginate.

resources of the region.

To initiate and support scientifi c research on water and the

These policy options are intended to considered by the international

environmental and socio-economic problems of the region.

scientifi c community, local, regional and international decision-makers,

funding bodies, and the general public, although at present, the latter is

At the regional level, it is recommended that: i) the existing system of

not suffi

ciently organised or powerful to act as a key stakeholder.

water resources management be reorganised; ii) a new multi-lateral

water sharing agreement be created; and iii) water pricing systems be

In conclusion, the water resources of transboundary basins in Central

introduced.

Asia are not optimally utilised, thus the freshwater shortage situation

remains unresolved and continues to deteriorate. Progress in this area

The tasks deserving special attention by the region's governments and

can be achieved through political rather than technical measures and

the international community are:

fi rstly requires the development of legal agreements at the national,

The creation of an interstate body empowered to implement

regional and international level.

eff ective and confl ict-free regional water resources management.

The development of a system of mutually acceptable political

and legislative decisions and measures in order to facilitate the

equitable and sustainable use of the region's water resources.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

13

Acknowledgements

This report presents the results of the Global International Waters Assessment

of the Aral Sea Basin, GIWA region 24. The assessment has been carried out by

a multidisciplinary team of international experts that included representatives

from each riparian country. Regional scientifi c institutions, such as the Russian

Academy of Science (RAS), Kazakhstan's Institute of Geography and Uzbekistan's

Hydrometeorology Institute all contributed to the assessment. The results were

discussed at the Regional Conference of GWP CACENA Stakeholders on the

17- 18th January 2005 in Bishkek and with the Committee for Water Resources of

the Ministry of Agriculture of Kazakhstan, IFAS, the Ministry of Nature protection of

Turkmenistan, and other local and regional authorities and executive bodies. The

Environment Programme (CEP) was also consulted.

14

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 24 ARAL SEA

Abbreviations and acronyms

ASBP-1 First

Aral

Sea

Basin

Program

IPPC

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

ASBP-2 Second

Aral

Sea

Basin

Program

IWP

Index of Water Pollution

CCA Causal

Chain

Analysis

IWRM Integrated

Water

Resources

Management

CDF Comprehensive

Development

Framework

MAC Maximum

Allowable

Concentration

CIA

Central Intelligence Agency

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

CIS

Commonwealth of Independant States

NPRS

National Poverty Reduction Strategy

CNR Commission

for

National

Reconciliation

SIC

Center of Scientifi c Information

DDT Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

SPECA

Special Programme for the Economies of Central Asia

FSU

Former Soviet Union

SRC ICWC Scientifi c-Research Center of Interstate Commission for

GDP Gross

Domestic

Product

Water Coordination of Central Asia

GEF Global

Environment

Facility

TACIS

Technical Assistance to the CIS

GFDL Geophysical

Fluid

Dynamics

Laboratory.

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

GIWA

Global International Waters Assessment

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

GNP Gross

National

Product

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientifi c and Cultural

ICG International

Crisis

Group

Organization

ICSD

International Commission on Sustainable Development

USSR

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

ICWC

Interstate Coordination Water Commission

UTO

United Tajik Opposition

IDA International

Development

Association

WTO World

Trade

Organization

IFAS

International Fund for saving the Aral Sea

IMF International

Monetary

Fund

INTAS

The Interrnational Association for the Promotion

of Co-operation with Scientists from the

New Independent States (NIS) of the Former Soviet Union

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

15

List of figures

Figure 1

Boundaries of the Aral Sea region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Figure 2

Vegetation types in the Aral Sea region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Figure 3

Mean air temperatures in January and July. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Figure 4

Annual precipitation in the Aral Sea region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Figure 5

Aerial view of meandering Syrdarya River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Figure 6

Correlation between mortality from infectious diseases (per 100 000 people) and a deviation of water quality from the accepted standards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Figure 7

Correlation between infant mortality rate (per 1 000 live births) and a deviation of water quality from the accepted standards. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

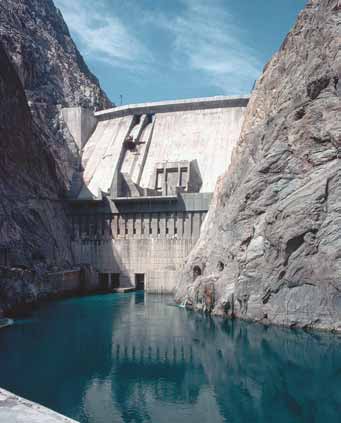

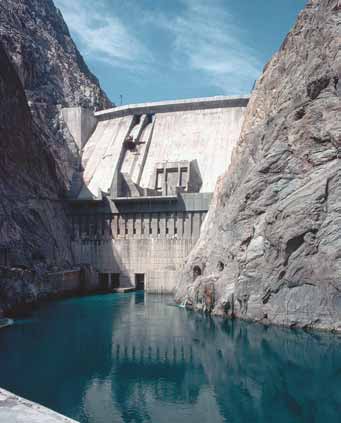

Figure 8

The Toktogul hydroelectric dam on the Naryn (Syrdarya) River, Kyrgyzstan. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Figure 9

Beached boat in a part of the Aral Sea which was once covered in water. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Figure 10

Peaks rising from a glacier in the Pamirs, Tajikistan. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Figure 11

Causal chain analysis model for the Aral Sea region.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Figure 12

Changes in surface area of the Aral Sea. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

List of tables

Table 1

Land resources of the Aral Sea Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Table 2

Mean annual river run-off in the Aral Sea Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Table 3

Water reservoirs in the Aral Sea Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Table 4

Ethnic composition of the population. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Table 5

Demographic characteristics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Table 6

Economic characteristics of the Aral Sea countries. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Table 7

Scoring table for the Aral Sea region. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Table 8

Groundwater reserves in the Aral Sea Basin and their uses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Table 9

Water pollution in Syrdarya River Basin. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Table 10

Salinity along the Amudarya River. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Table 11

Change in salinity along some rivers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Table 12

Historical changes in salinity in some rivers in the Amudarya and Syrdarya basins. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

16

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 24 ARAL SEA

Regional defi nition

This section describes the boundaries and the main physical and

Boundaries of the region

socio-economic characteristics of the region in order to defi ne the

area considered in the regional GIWA Assessment and to provide

According to the GIWA regional boundaries, the Aral Sea region includes

suffi

cient background information to establish the context within

the territory of three closed water basins - the Aral Sea, Lake Balkhash

which the assessment was conducted.

and Lake Issyk Kul. Each of these basins has specifi c natural and socio-

economic features which should be evaluated separately. This report

T

focuses on the Aral Sea Basin exclusively, which is

Russia

obol

situated between 55°00' E and 78°20' E and 33°45' N

and 51°45' N and has a total area of 2.7 million km2

Turgay

(2.4 million km2 within the border of fi ve former

republics of the USSR) (Bortnik & Chistijaeva 1990)

(Figure 1).

su

Sary

Kazakhstan

The Aral Sea Basin includes the basins of the Syrdarya

A r a l S e a

and Amudarya rivers which fl ow into the Sea, and

su

ry

Sa

the Tedzhen and Murgabi rivers, the Karakum canal,

Chu

and shallow rivers fl owing from Kopet Dag and

western Tien-Shan, as well as closed areas near these

rivers and the Aral Sea (Figure 1). Administratively,

Uzbekistan

arya

Bishkek

the region entirely covers Uzbekistan and Tajikistan,

Am

yrd

S

udar

some parts of Kazakhstan (the Kyzylorda and

ya

Tashkent

Naryn

ya

Syrdar

Kyrgyzstan

Shimkent regions and the southern part of the

Turkmenistan

Aktyubinsk region), Kyrgyzstan (the Osh and Naryn

Vakhsh

Karakum

Dushanbe

regions), Turkmenistan (excluding the Krasnovodsk

skiy Kanal

Tajikistan

region), and part of northern Afghanistan and

b

Murgab

a

Mashhad

h

Elevation/

northeastern Iran. This assessment does not focus

Murg

ndz

n

Karamb

Depth (m)

ar

eh

Pya

on the latter two countries and when the report

Iran

edz

4 000

T

Afghanistan

2 000

discusses `the fi ve countries of the region' it does

1 000

Harirud

500

not include these, but is referring rather to the fi ve

100

0

-50

former Soviet countries of the region.

-200

-1 000

0

500 Kilometres

-2 000

© GIWA 2005

Figure 1

Boundaries of the Aral Sea region.

REGIONAL DEFINITION

17

Physical characteristics

Soil and vegetation

The region is dominated by zonal semi-desert, semi-bush and desert

Geological composition and relief

dispersed bush and graminaceus vegetation (Figure 2). Semi-deserts

The geological composition and relief form the lithogenic background

and deserts cover approximately one third of the regions' surface.

of the geographical landscape. Figure 1 shows the main physio-

geographical features of the Aral Sea region. The territory is

The region contains the following soil and vegetation zones:

heterogeneous in terms of its geology. The plain-lands belong to the

Dry steppe with feather grass and tipchack vegetation, found upon

Turanian plate of the Gercian platform, where a deep covering layer

the chestnut (brown) soils, which cover approximately one quarter

(more than 10 km thick) of Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments lies upon

of the territory (northern part);

highly rugose Paleozoic sediments.

Semi-deserts with grass and shrubby vegetation, situated on lurid

(dark brown) semi-desert soils;

The mountainous areas of the region (the Pamirs, Tien-Shan, Pamiro-

Deserts of the temperate climatic belt with grey and brown soils;

Alay) comprise of newly formed rugose geological structures, which

Sands of semi-deserts and deserts with sporadic vegetation cover,

originate from the same plate formed in the Neogene period of the

which support a high diversity of plant species, but with limited soil

Cenozoic aeon. Continental neogene-quaternary sediments are found

cover. For example the Karakum desert hosts 827 species of higher

above this layer, which were formed by river processes and temporary

plants. The area is characterised by the anthropogenic degradation

water fl ows, as well as sea transgressions and aeolic (dust) processes.

of forests;

Grey soils of semi-deserts where trees and perennial vegetation

The geological constitution has a signifi cant impact on the relief and

prevail. Desertifi cation is observed and there has been degradation

landscape of the territory. The relief of the territory can be divided into

of steppes (grassy communities) as a result of agricultural activities,

two types: plain and mountainous.

and the savannahs (complexes of trees and grassy vegetation) due

to the salinisation of soils;

The plain relief is found in the Kazakh tableland (nipple-land) and

Xerophytic forests and bushes of the foothills and low mountains,

Turanian lowland. The Kazakh nipple-land covers the northern part

found upon brown and grey-brown soils;

of the plain and is actually a peneplain (hilly, elevated plain), which in

Wide-leaf forests situated upon mountainous grey and dark brown

some places is occupied by low-lying residual mountains. It is generally

soils.

200-500 m high, but the residual mountains of Ulu-Tau are over 1 100 m

in height.

Russia

Zone

The Turanian lowland is situated on the Turanian plateau, which

Desert

Forest

has predominantly fl at monotonous relief (-43 m in Sary-Kamysch

Intrazonal

depression), which rises to about 200 m above sea level (Sultan-

Open woodland

Semidesert and desert

Wis-Dag). This area contains alluvial and sea formed lowland plains,

Steppe

Kazakhstan

with benches and dry seabeds. It encompasses the southern areas

A r a l

S e a

of the plain territory. The arenaceous deserts Karakum, Kyzilkum

and Muyunkum are characterised by aeolic sandhills and ridges. The

elevated plateau of Usturt is located in the south of the region.

Uzbekistan

Bishkek

Tashkent

The Turanian lowland is bordered by the foothills of the Kopet-Dag

Turkmenistan

Kyrgyzstan

mountains and Parapamize (in Turkmenistan). To the southeast of the

Dushanbe

Tajikistan

territory, the catchment area is partially occupied by foothills and the

Mashhad

high mountains of Pamirs, Pamiro-Alai and Tien Shan, which are covered

Iran

Afghanistan

by more than 800 mountain glaciers.

© GIWA 2005

Figure 2

Vegetation types in the Aral Sea region.

18

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 24 ARAL SEA

Intrazonal soils are formed locally in river valleys and especially along

Biodiversity

broad deltas, and under "tugays" (periodically inundated forested

Biodiversity in the region is determined by the plain, sub-mountain and

areas). Permanent or periodically excessive humidifi cation results in

mountain landscapes, as well as the considerable latitudinal extension

the growth of tugay forests and bushes on alluvial soils.

of the region (almost 20° latitude). Mountain regions are characterised

by altitudinal and horizontal zoning with a high level of heterogeneity

Land use

caused by relief peculiarities. The highest numbers of endemic species

Central Asia's prosperity is strongly linked with the patterns of land

are observed in the isolated habitats. The relatively homogeneous

use development. At present, the total area of potential arable land is

structure of the fl at landscapes of the region becomes more complex

59 million ha, of which only 10 million ha are actually being cultivated

closer towards the mountain areas. The regional fl ora includes 1200

(Table 1).

species of anthophyta (fl owering plants) and 560 species of woody

vegetation, including 29 endemic species of Central Asia. The fl ora of

Table 1

Land resources of the Aral Sea Basin.

the Aral Sea coast includes 423 species of plant (Novikova 2001).

Potential arable

Total area

Arable area

Irrigated area

Country

area

(ha)

(ha)

(ha)

(ha)

Climate and climatic variability

Kazakhstan*

34 440 000

23 872 400

1 658 800

786 200

Owing to the extreme remoteness of the region from the oceans, it

Kyrgyzstan*

12 490 000

1 570 000

595 000

422 000

has a distinct continental climate. It is not subject to the monsoons of

Tajikistan

14 310 000

1 571 000**

874 000

719 000

Southern Asia as it is separated by high mountains, and it is seldom

Turkmenistan

48 810 000

7 013 000

1 805 300

1 735 000

subject to cyclones from the west.

Uzbekistan

44 884 000

25 447 700

5 207 800

4 233 400

Aral Sea Basin

154 934 000

59 474 100

10 140 900

7 895 600

The radiation balance (kkal/ cm2 annually) in the marine area of the

Notes: *Territories within the Aral Sea Basin. ** Areas suitable for irrigation.

Aral Sea averages as R=55.7. It is characterised in this region by an

(Source: FAO 1997)

absolute predominance of turbulent fl ows of heat compared with the

Half of the cultivated land belongs to the oasis, where it is naturally

expenditures of heat from the transpiration of moisture, whereas on

drained and the soil is fertile. The rest of the potential arable land would

the majority of the earth's surface there is a reverse interrelationship

require complex and costly development, including drainage, landscape

between these two parameters.

modifi cation and improvements in soil structure (SPECA 2004).

To

T

ob

bo

ol

January

Russia

l

Temperature

Russia

July

(°C)

-40

Turgay

Turgay

-30

-20

-10

0

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan

su

su

10

Aral

Sary

Aral

Sary

Sea

20

su

Sea

su

Sary

Sary

30

Chu

Chu

more

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

a

a

r

'

y

r

'

y

a

a

d

r

d

yr

Bishkek

y

Bishkek

S

S

Tashkent

Tashkent

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

Naryn

Naryn

Syrdar'ya

Kyrgyzstan

Syrdar'ya

Kyrgyzstan

Am

Am

ud

ud

a

a

r

Vakhsh

Vakhsh

'y

r

'y

a

a

Te

Kara

Dushanbe

Te

K

Dushanbe

k

a

um

ra

dz

k

s

um

ki

dz

y K

ski

he

a

y K

na

h

a

l

na

en

l

n

Tajikistan

Tajikistan

Mashhad

Mashhad

Murgab

Murgab

b

h

ab

zhd

a

dz

rg

n

r

g

n

ya

u

Mu

ya

P

M

P

Iran

Karambar

Iran

Karambar

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Harirud

Harirud

GIWA 2005

Figure 3

Mean air temperatures in January and July.

REGIONAL DEFINITION

19

The region is characterised by large variations in temperature and

Table 2

Mean annual river run-off in the Aral Sea Basin.

precipitation (Figure 3 and 4). The aridity of the climate increases in the

Annual river run-off (km3)

Aral Sea Basin

centre of the region. Annual precipitation ranges from 1 500 -2 500 mm

Country

Syrdarya

Amudarya

Aral Sea

(%)

at the glacier belts of West Tien Shan and West Pamir, to 500-600 mm at

Basin

Basin

Basin

Kazakhstan

2. 43

-

2.43

2.1

the foothills, and to 150 mm at the latitude of the Aral Sea. To the north

Kyrgyzstan

26.85

1.60

28.45

24.4

of this latitude, in Northern Kazakhstan, annual precipitation increases

Tajikistan

1.00

49. 58

50.58

43.4

to between 250 and 350 mm.

Turkmenistan

-

1.55

1.55

1.3

Precipitation

Uzbekistan

6.17

5.06

11.22

9.6

Russia

(mm/year)

Afghanistan and Iran

-

21.59

21.59

18.5

0-100

100-200

China

0.756

-

0.756

0.7

200-600

Total for the Aral Sea Basin

37.20

79.38

116.58

100

600-1 400

(Source: Kipshakbayev & Sokolov 2002)

1 400-2 800

Kazakhstan

2 800-5 600

Aral

5 600-10 000

territorial distribution of renewable water resources and a high degree

Sea

of variation in inter-annual run-off . About 43% of the Aral Sea Basin

resources are formed in the territory of Tajikistan and more than 24%

Uzbekistan

in the territory of Kyrgyzstan. A considerable fraction of surface run-

off resources (18.6%) is also formed in the territories of Afghanistan

Turkmenistan

Kyrgyzstan

and Iran (table 2). The main consumers of water resources, however,

are Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. The annual river run-

Tajikistan

off fl uctuates between a maximum volume 1.5-2.5 times greater,

Iran

and a minimum 2.0-2.2 times less, than the average annual run-off

Afghanistan

(Shultz 1965, Bolshakov 1974, Kipshaskbayev & Sokolov 2002). With an

arid climate and increasingly defi cient water resources such run-off

variations present an extreme risk for irrigated farming.

GIWA 2005

Figure 4

Annual precipitation in the Aral Sea region.

Rivers

The majority of the Aral Sea region belongs to the basins of the two

Hydrological characteristics

major rivers - the Amudarya and Syrdarya. The territory of the Tadjen,

The term "water resources" in this region refers to the annual volume

Murghab, Chu and Talas rivers orographically belong to the Aral Sea

of river fl ow measured where headwaters leave the mountains for the

Basin but the waters are exploited for irrigation or are lost on the sub-

lowlands and upstream of water intake structures used for irrigation.

mountain plain and do not reach the Aral Sea.

Table 2 shows the mean annual surface river run-off in the Aral Sea

Basin. The Amudarya Basin receives far greater water in the area of run-

The mountainous areas play an important role in maintaining the

off formation (0.256 km3/km2 per year compared to 0.170 km3/km2 per

ecological integrity and food security for the entire region. They only

year in the Syrdarya Basin), with 62% of its annual river run-off formed

occupy about 20% of the total area of the Aral Sea Basin but are the

on the territory of Tajikistan. The Aral Sea is supplied with 68% of its

source of approximately 75% of renewable water resources and contain

renewable water resources by the Amudarya Basin. It should be noted

freshwater resources within glaciers and underground ice; a reliable

that table 2 does not take into account the run-off from the Chu and

guarantee of stable river fl ow for the future.

Talas rivers, which orographically belong to the Aral Sea Basin. Taking

these waters into account, the total water resources in the Aral Sea Basin

The Aral Sea

is 123.6 km3 (Chub 2000).

Origins of civilisation and farming in the Aral Sea Basin can be traced

back 2 000 years. Natural environmental variance and human activity

Water supply in the region is not only aff ected by the modifi cation

have led to signifi cant ecological changes in the Aral Sea Basin.

of the main transboundary rivers in the region, but also by their

hydrological regime, which is characterised by an extremely irregular

20

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 24 ARAL SEA

Prior to the 1960s, the Aral Sea comprised an area of 68 300 km²,

Mountains. The total lake volume is 17 km3. Lake Sarez is under constant

including a water surface area of 66 100 km² and islands of 2 200 km².

observation by the government of Tajikistan and the international

The volume of seawater amounted to 1 066 km³ (Hurni et al. 2004,

community due to the possibility that the lake's dam could burst,

Bortnik & Chistjaeva 1990). The maximum depth of the Sea is 69 m,

putting an area of more than 5 000 km2 and over 5 million people at

but depths of less than 30 m are common in a large proportion of

risk (Olimov 2001).

the sea. The average sea level, meanwhile, fl uctuates between 52 to

53 m. Mineralisation of the Aral Sea waters over the past 100 years

The largest lakes in the low-lying areas of the Aral Sea Basin are

of instrumental observations has varied within a range of 10-12 g/l

situated in Uzbekistan and partially in Kazakhstan, in the lower and

(Glazovsky 1990 and 1995, Amirgaliev & Ismuchanov 2002).

middle reaches of the Amudarya and Syrdarya. The largest of them

were formed by drainage waters, which today consist predominantly

Historically, the Sea has risen and fallen considerably. During the

of drainage effl

uent from irrigated areas. The largest of these lakes

Quaternary period, variations in the level of the Aral Sea were as much

are Aydarkul (surface area of 30 km2), Sarykamysh (8 km2), Sudochye

as 36 m. In the fi rst half of the twentieth century the variance in sea level

and Parsankul (2 km2 each). The fi rst of the above-mentioned lakes

did not exceed 1 m, and the ecological situation was quite stable up to

is situated in the Arnarsay depression at the boundary between

the end of the 1950s. However, substantial variations have taken place

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan; its total volume is about 30 km3. It was

during the last 40 years, and this report focuses on this time period.

formed by the discharge of excess water from Chardarya water reservoir

(mainly due to winter water discharges from Tokhtogul water reservoir)

Decreased river infl ow since the early 1960s has changed the water

and drainage waters from the irrigated fi elds of the Golodnaya steppe

budget of the Aral Sea. By 1990, the area of the Sea had decreased to

in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

34 800 km² and its volume to 304 km³ (Glazovsky 1995), and since the

end of the 1950s the level of the Sea had fallen by more than 22 m

The majority of the once numerous and biologically productive

(Amirgaliev & Ismuchanov 2002). A signifi cant proportion (about

freshwater lakes in the delta of the Amudarya and Syrdarya have

33 000 km²) of the sea fl oor has dried up, the confi guration of the

completely dried up or lost their economic value, constituting one

shoreline has changed, and water mineralisation has increased from

of the most important and dramatic consequences of the irrational

10-12 in the 1930-1960s to 83-85 in 2002 (Amirgaliev & Ismuchanov

use of water resources in the Aral Sea Basin. It has caused the rapid

2002). Today the inland sea covers about half of its former area and its

degradation of the delta landscapes and an abrupt reduction in the

water volume has decreased by about 75%. As water mineralisation

biodiversity of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

increased, the spawning sites of fi sh disappeared and the forage reserve

depleted, which led to a decline in fi sh resources. Only fi ve species of

Water reservoirs

fi sh remain and nearly all limnoplankton and numerous haloplankton

The total volume of water reservoirs in the Aral Sea Basin is over 74 km3

became extinct (Aladin 1999, Aladin & Kotov 1989, Aladin et al. 2001,

(Table 3). The largest is Tokhtogul reservoir, which has a total volume

Treshkin 2001).

of 19.5 km3 and a useful volume of more than 14 km3. All of the large

water reservoirs have multi-purposes, but are mainly used for power

Lakes

generation and irrigation. On the territory of Uzbekistan, in addition to

There are more than 5 000 lakes in the Aral Sea Basin, of which more

numerous ponds and small-capacity water reservoirs used for irrigation,

than 4 000 are situated in the Amudarya and Syrdarya basins. Most

50 relatively large reservoirs with a total volume of 19 km3 have been

of the lake water reserves are concentrated in the Amudarya Basin

constructed.

(46 km3), whereas water reserves in the Syrdarya Basin only amount to

4 km3 (Chub 2000&2002, Chub & Myagkov 2002). The majority of these

A total of 45 hydropower plants with a total capacity of 34.5 GWh/year

lakes are of small area and limited volume, with many low-lying plain

were constructed on the largest reservoirs. The Nurek hydropower

lakes drying out in extremely dry years.

station on the Vakhsh River in Tajikistan (2 700 MWh/year) and the

Tokhtogul hydropower station (1 200 MWh/year) on the Naryn River in

Lake Karakul, a high-mountainous closed lake located in the Eastern

Kyrgyzstan are the largest (Kipshkbayev & Sokolov 2002, Duskayev 2000,

Pamirs, is the largest lake in the region with a water volume of more

Burlibayev et al. 2002, Mamatkanov 2001). Of all the countries of the Aral

than 26 km3. Lake Sarez was formed as the result of a tremendous

Sea Basin Tajikistan has the greatest hydroelectric potential of all the

landslide during an earthquake in 1911 and is also located in the Pamirs

countries in the Aral Sea Basin - more than 52 000 GWh/year.

REGIONAL DEFINITION

21

Table 3

Water reservoirs in the Aral Sea Basin.

of the population, Kazakhs (16.8%) and Russians (13.4%). In the fi ve

Water-storage

countries of the region the indigenous population dominate, especially

Largest water-storage reservoirs

reservoirs

Country

in Uzbekistan (80%) and Turkmenistan (77%). The highest percentage

Capacity

Capacity

Number

Name

River

(km3)

(km3)

of small ethnic groups united in the table under the heading "Other"

Kazakhstan

1

5.7

Chadarya 5.7

Syrdarya

is registered in Kyrgyzstan (11.8%) and Kazakhstan (8%). These are the

Tokhtogul

19.5

Naryn (Syrdarya)

most ethnically diverse countries.

Kyrgyzstan

13

23.5

Kirov

0.55

Talas

Orto-Tokay 0.47

Chuy

In general, the region is characterised by high population growth rates

Nurek

10.5

Vakhsh

(except in Kazakhstan), a negative balance of migration and a high infant

Tajikistan

19

29.0

Kayrakum

4.16

Syrdarya

mortality rate. The demography of Kazakhstan diff ers from the other

Nizhne-Kafirighan

0.9

Kafirnighan

countries due to its low rate of population growth (0.1), the greatest

Turkmenistan

18

2.86

Naue-Khan

0.88

Karakum canal

negative balance of migration (-6.16 migrants/1 000 population) and

Charvak

1.99

Charvak (Syrdarya)

the smallest percentage of the population living below the poverty line

Uzbekistan

50

19.0

Andizhan

1.90

Karadarya (Syrdarya)

(26% as compared with 34-80% in other countries of the region).

(Source: Kipshkbayev & Sokolov 2002, Duskayev 2000, Burlibayev et al. 2002, Mamatkanov 2001)

According to estimations it is technically feasible to harness about half

Kazakhstan has the smallest percentage of young people (under 15

of this potential energy. Until now only about 4 GWh/year have been

years old) in the region, accounting for only 26% of the population,

utilised.

whereas in the other countries of the region this fi gure ranges from 34

to 40%. Kazakhstan also has the highest proportion of the population

that are older than 65 (7.5%) (Table 5). These factors combined with the

lowest birth rate (17.83 births/1 000 population as compared with 26-

Socio-economic characteristics 32/1 000 in other countries) and the highest death rate in the region

(10.69/1000 population in 2002) may induce social and economic

Demographic characteristics

problems in the near future. It is also worth noting that Kazakhstan

Recent population growth fi gures may not be representative of future

trends. There is likely to be a decline in population growth rates, but it is

Table 4

Ethnic composition of the population.

not known by how much and when this is to occur. In principle, smaller

Ethnic group (%)

State

families will be desirable for the urban population, but for subsistence

Kazakh

Kyrgyz

Uzbek

Tajik

Turkmen Russian Ukrainian

German

Other

farmers it will remain attractive to have larger families, with more than 4

Kazakhstan

53.4

-

-

-

-

30.0

3.7

2.4

8.0

children. In any case, in the next 25 years the population of the region is

Kyrgyzstan

-

52.4

-

-

-

18.0

2.5

2.4

11.8

predicted to grow due to the age structure of the present population.

Uzbekistan

3.0

-

80.0

5.0

-

5.5

-

-

6.5

Tajikistan

-

-

25.0

64.9

-

3.5

-

-

6.6

Table 4 shows the ethnic breakdown of the population of each country

Turkmenistan

2.0

-

9.2

-

77.0

6.7

-

-

5.1

in the Aral Sea Basin, excluding Afghanistan. There are three dominant

Total

16.80

4.31

40.3

9.63

6.17

13.40

2.26

0.88

7.26

ethnic groups in the region: Uzbeks, who account for more than 40%

(Source: CIA 2002)

Table 5 Demographic

characteristics.

Migration

Infant

Life expectancy at birth

Total health expenditure

Death rate

Age structure

Growth rate

rate

mortality

Birth rate

Country

Population

(deaths/

(%)

(migrate/

rate (deaths/

Per capita

(births/1 000)

Female

Male

% of GDP

1 000)

0-14 (%)

15-64 (%)

1 000)

1 000)

(USD)

Kazakhstan

16 741 519

0.1

-6.16

58.95

69.01

58.02

211

3.7

17.93

10.69

26.0

66.5

Kyrgyzstan

4 822 166

1.45

-2.51

75.92

67.98

59.35

145

6.0

26.11

9.10

34.5

59.4

Uzbekistan 25

563

441

1.62

-1.94

71.72

67.60

60.38

86

3.7

26.09

7.98

35.5

59.8

Tajikistan

6 719 567

2.12

-3.27

114.77

67.46

61.24

29

2.5

32.99

8.51

40.4

54.9

Turkmenistan

4 688 963

1.84

-0.98

73.21

64.80

57.57

286

5.4

28.27

-

37.3

58.6

Total

58 435 656

(Source: CIA 2002, World Bank 2002)

22

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 24 ARAL SEA

has a relatively high level of social welfare for its population, which

of Kazakhstan also has the highest real growth of GDP in the region

is explained by the country having the greatest GDP/per capita

(12.2% as compared with 3-10% in other countries), a positive export

(5 900 USD) in the region, the highest percentage of elderly people, and

and import balance (2.3 billion USD), relatively low infl ation (8.5%)

relatively high expenditure on health care (211 USD per capita) (Table 5).

and low unemployment (Table 6). Kazakhstan also has the lowest

In contrast, Kyrgyzstan has the lowest percentage of elderly people in

population percentage living below the poverty line. The ratio of the

the region (less than 1%), which relates to the low level of social welfare.

contribution of the industrial sector in comparison to the agricultural

Tajikistan has the highest level of infant mortality (114.7deaths/1 000

sector towards the formation of GDP is 3.0, which is 1.8-4.6 times higher

live births), the highest birth rate (33.0/1 000 population), the lowest

than the corresponding ratio for the other countries in the region. In

GDP (1 140 USD per capita), the greatest percentage of the population

2003 GDP increased by 9.2%, the share of industrial output increased

living below the poverty line and the highest unemployment rate - 20%

by 8.7%, foreign trade by 8.3%, and investments into fi xed assets by

compared with 7-10% in the other countries (Table 5).

17.2%. Defi ciency of the budget in 2003 was less than 1% of GDP and

real wages increased by 8.3%. The general fi ve year growth of GDP in

Economic characteristics

Kazakhstan meant that in 2003, GDP had increased by 6.3% compared

Table 6 outlines the economic characteristics of the countries in the

to 1991.

region. Unfortunately the data for Turkmenistan is not complete.

Kazakhstan has undergone the most successful economic development;

The break-up of the USSR and the severe decline in demand for heavy

it has the highest GDP (98 billion USD), which is almost one third higher

industrial products from Kazakhstan resulted in the short-term collapse

than that of Uzbekistan and more than ten times that of Tajikistan. The

of the economy, with the steepest annual decline recorded in 1994.

poorest economic situation can be found in Tajikistan. In general, the

Between 1995 and 1997, the pace of economic reform and privatisation

region has experienced positive economic tendencies in recent years.

quickened, resulting in a substantial shifting of assets to the private

In Kazakhstan GDP growth has exceeded 6-7% over the last fi ve years.

sector. In 1993, Kazakhstan began a comprehensive structural reform

programme aimed at moving towards a market economy which was

Kazakhstan

internationally supported by bilateral and multilateral donors, including

Kazakhstan, the largest of the former Soviet republics excluding

the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Russia, is rich in fossil fuel resources and has plentiful supplies of other

minerals and metals, including gold, iron ore, coal, chrome and zinc.

Today, poverty in the country persists. In 2001, approximately 28% of

It also has a thriving agricultural sector in the areas of livestock and

the population were earning below the minimum subsistence level. A

grain production. There are vast areas of arable land. The agricultural

considerable proportion of the population has no access to potable

and the industrial sectors' share of GDP is estimated at 15% and 30%,

water and suff ers from the eff ects of pollution and environmental

respectively. Kazakhstan's industrial sector relies on the extraction

degradation.

and processing of natural resources and also on a growing sector

specialising in the construction of equipment, agricultural machinery

In 2000 and 2001, Kazakhstan experienced economic growth due to its

and defence technology.

booming energy sector, economic reform, good harvests, and foreign

investment. The opening of the Caspian Consortium pipeline in 2001,

Kazakhstan has a relatively high standard of infrastructure and the

from western Kazakhstan's Tengiz oilfi eld to the Black Sea, substantially

contribution of the services sector to the GDP is 60%. The economy

raised export capacity. The industrial policy in Kazakhstan is designed

Table 6

Economic characteristics of the Aral Sea countries.

GDP

Population

Industrial

Budget

below

production

Export

Import

Inflation rate Unemployment

State

Purchasing power parity

(million USD)

Per

Agriculture Industry

poverty line

growth rate

(million USD)

(million USD)

(%)

rate (%)

Total

Real growth

capita

(%)

(%)

(%)

(%)

(billion USD)

rate (%)

Kazakhstan

4 200

98.1

12.2

5 900

10

30

26.0

11.4

10 500

8 200

8,5

10.0

Kyrgyzstan

207

13.5

5.0

2 800

38

27

55.0

6.0

475

420

7.0

7.2 (1999)

Uzbekistan

4 000

62.0

3.0

2 500

33

24

-

3.5

2 800

2 500

23.0

10.0

Tajikistan

-

7.5

8.3

1 140

19

25

80.0

10.3

640

700

33.0

20.0

Turkmenistan

589

21.2

10.0

4 700

27

45

34.4

-

2 700

2 300

10.0

-

(Source: CIA 2002, World Bank 2002)

REGIONAL DEFINITION

23

to direct the economy away from overdependence on the oil sector

aid for development programmes in Kyrgyzstan over the past fi ve years,

by developing light industry (CIA 2002). Infl ation decreased from an

poverty remains a signifi cant issue in the country (UNDP 2003).

annual rate of 29% in 1996 to only 6.4% in 2003. In 1996, GDP growth

was estimated at 0.5%, compared to 9.2% in 2003.

Recent economic development is beginning to show as a result of

these measures. The rate of infl ation declined from 1 000% in 1993 to

Kyrgyzstan

15% in 1997. Following a cumulative decline of approximately 51% in

Kyrgyzstan is a small mountainous country with an economy

1991-1995, GDP grew by 7% in 1996 and 1997, by 6.7% in 2003 and 7.1% in

predominantly based on agriculture. The country has undergone

2004 (ICWC 2004). After concerted eff orts to attract private capital and

an economic transformation following the dissolution of the Soviet

interest to the mining sector, the Kumtor gold mine, the eighth largest

Union. Cotton and wool constitute the main agricultural products

in the world, began production in 1997 and achieved commercial levels

and exports. Industrial exports include gold, mercury, uranium, and

in May 1997, adding 4% to GDP. Agriculture, the largest sector in the

electricity. Kyrgyzstan has been one of the most progressive countries

economy of Kyrgyzstan, accounted for 45% of GDP and for half of the

of the former Soviet Union in carrying out market reforms.

total employment in 1997 (UNESCO 2000).

Policymakers have had diffi

culties dealing with the termination of

The production of most crops declined considerably between 1990

budgetary support from Moscow, the disruption of the former Soviet

and 1995 but has begun to recover more recently. Livestock and wool

Union's trade system and a large deterioration in the Kyrgyzstan

production however, two of the mainstays of the rural economy, have

Republic's terms of trade, primarily owing to large increases in import

declined severely and still remain depressed. Agro-industry faced crisis

prices of oil and natural gas. By 1999, GNP had declined to 260 USD per

between 1990 and 1996, with annual production declining by over 90%

capita, with severe declines in living standards.

for most commodities. In recent years state support has stimulated

growth in the agrarian sector.

Early reforms by the Government included the liberalisation of

most prices, the creation of a national currency, the introduction

Government intervention in agricultural marketing has largely

of a liberal trade regime, and the elimination of most capital fl ows.

disappeared. The foreign trade regime and prices have been

Substantive progress in tightening fi scal policies followed in parallel

liberalised. Over 65% of the agro-business has been privatised and

with a successful reform of the fi nancial sector, and monetary policy

demonopolised.

framework and instruments. In 1994, deposit and interest rates were

liberalised, directed credits were discontinued, and domestic fi nancing

However, the government and the international fi nancial institutions

of the budget defi cit was sharply curtailed.

have embarked on a comprehensive medium-term poverty reduction

and economic growth strategy. In November 2001, with fi nancial

On July 17, 1998, the Kyrgyz Republic successfully concluded World

assurance from the Paris Club, the IMF Board approved a three-year

Trade Organization (WTO) accession negotiations, paving the way for

93 million USD Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (CIA 2002).

the Kyrgyz Republic to become the 133rd and the fi rst Commonwealth

of Independent States member to join the WTO.

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is a dry, landlocked country of which 11% of the territory

In 2001 infl ation was lowered to an estimated 7%. Much of the

consists of intensely cultivated, irrigated river valleys. More then 60%

government's stock enterprises have been sold. Production had

of its population live in densely populated rural communities. The

severely declined since the break-up of the Soviet Union, but by 1995

country possesses signifi cant economic potential with a well educated

production had begun to recover and increase. Growth increased from

population and qualifi ed labour force. Uzbekistan is rich in natural

2.1% in 1998 to 5% in 2000, and again 5% in 2001. Nevertheless, poverty

resources such as gold, natural gas, oil, coal and copper. It is the world's

remains acute: approximately 40% of the Kyrgyz population lives in

ninth largest producer of gold (with an annual output of approximately

poverty, with 51% and 41% of the population in 2001 living in poverty in

60 tonnes) and is among the largest suppliers of natural gas (with an

rural and urban areas, respectively. In September 2002, the Government

annual production of more then 50 billion m3). In spite of its potential,

released the National Poverty Reduction Strategy (NPRS): 2003-2005,

Uzbekistan presently remains an underdeveloped country. Its GNP per

one element of the Comprehensive Development Framework (CDF) of

capita was estimated at 350 USD in 1999.

the Kyrgyz Republic to the year 2010. Despite substantial international

24

GIWA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT 24 ARAL SEA

Figure 5

Aerial view of meandering Syrdarya River.

(Photo: CORBIS)

More than 20% of Uzbekistan's GDP is generated in agriculture, which

In 1997 and during the fi rst half of 1998 economic trends were mixed. In

employs about 49% of the country's labour force. Primary commodities,

an eff ort to curb accelerating infl ation and a widening current account

such as cotton fi bre, mining and energy products, account for about 75%

defi cit, the authorities started tightening fi scal policies at the beginning

of its merchandise exports; cotton alone accounts for 40% of exports.

of 1997. As a result, macroeconomic performance began to improve

The cautious approach to reform, combined with a focus on developing

again. According to offi

cial statistics, real GDP grew by 5.2% in 1997 and

self-reliance in energy and improving the mining and agricultural

by 4.0% in the fi rst half of 1998, while average monthly consumer price

sectors including trade diversifi cation (especially of cotton export),

infl ation fell to 2.1% in 1997 and to 1.7% in the fi rst half of 1998. The IMF's

allowed Uzbekistan to avoid an output collapse recorded in many other

estimates suggest that the GDP growth in 1997 may have been only

former Soviet Union countries during the fi rst years of independence.

2.4%, while average monthly infl ation was estimated at about 3.5%.

Uzbekistan's GDP declined by less than 145 USD in 1991-1993, compared

with a former Soviet Union average of almost 40% (UNESCO 2000).

Uzbekistan is now the second largest cotton exporter, a large producer

of gold and oil, and a regionally signifi cant producer of chemicals

Uzbekistan has introduced some elements of a market system over the

and machinery. Following independence in 1991, the government

past decade (for example privatisation and capital markets). However,

sought to support its Soviet-like command economy with subsidies

the government has opposed, to varying degrees, the following: trade

and tight controls on production and prices. The state continues

liberalisation; currency convertibility and a unifi ed exchange rate; full

to be a dominating infl uence in the economy and has so far failed

price liberalisation; the elimination of government interference into the

to bring about necessary structural changes. The IMF suspended

key sectors of the economy (e.g. cotton production); and central bank

Uzbekistan's 185 million USD standby arrangement in late 1996

independence.

because of governmental steps that made impossible the fulfi lment

REGIONAL DEFINITION

25

of a Fund contribution. Uzbekistan has responded to the negative

fi scal performance has also been impressive, with the fi scal defi cit (on

external conditions generated by the Asian and Russian fi nancial crises

a cash basis) in the last quarter of 1997 narrowing to only 0.2% of GDP.

by emphasising import substitute industrialisation and tightening

During the fi rst quarter of 1998, the defi cit was 1.6% of GDP. Owing to

export and currency within its already closed economy. Economic

the restored macroeconomic stability and the availability of external

policies that have repelled foreign investment are a major factor in the

fi nancing for cotton production, GDP grew by 1.7% in 1997; the fi rst

economy's stagnation. A growing debt burden, persistent infl ation, and

real growth since independence in 1991. The recovery has continued,

a poor business climate led to disappointing growth in 2001. However,

with real GDP in the fi rst quarter of 1998 estimated to be 1.3% over the

in December 2001 the government voiced a renewed interest in

corresponding period in 1997.

economic reform, seeking advice from the IMF and other fi nancial

institutions (CIA 2002).

Tajikistan has the lowest GDP per capita among the 15 former Soviet

republics, the highest unemployment in the region and 80% of the

Tajikistan

population lives below the poverty line. Tajikistan has a negative

The Republic of Tajikistan has inherited a developed infrastructure

export-import balance and the highest infl ation level. At the same time

and a well-organised and varied industrial and agricultural basis from

Tajikistan has one of the highest rates of GDP growth in the region (only

its former Soviet period. However, transition to the market type of

Kazakhstan has greater GDP growth).

economy has led to serious changes in the economic system and in

the economic links between the countries of the region. As a result of

Cotton is the most important crop. Mineral resources, varied but

confl ict, economic stagnation, and changes in the structure of export

limited, include silver, gold, uranium, and tungsten. Industry consists

and import, the level of industrial output dropped by 60%, a fi gure

of a large aluminium plant, hydropower facilities, and small obsolete

which only started recovering at the end of the 1990s. The agrarian

factories, mostly in light industry and food processing. The availability

sector plays a major role in the modern economy of Tajikistan, but

of hydroelectric power has infl uenced the pattern and structure of the

the industrial sector is less signifi cant. To stop the deterioration in

industrial sector, with aluminium, chemicals and other energy-intensive

economic conditions, the government introduced several reform

industries as the sector's mainstays. The civil war (1992-1997) severely

measures in 1995, including fi scal retrenchment and price liberalisation,

damaged the already weak economic infrastructure and caused a sharp

supported by an IMF Stand-by arrangement and an IDA rehabilitation

decline in industrial and agricultural production. On independence in

credit in 1996. In the following two years the policy performance of

1991, the collapse of the trade and payments system among former

Tajikistan was mixed, largely because of the renewed confl ict and

Soviet Union countries triggered a precipitous decline in output. As a

weak institutional capacity. Much of the reform agenda contained in

result, national poverty increased, particularly in the more remote and

the above credit was eroded or even reversed because of the confl ict

war aff ected areas, with as much as 85% of the population considered

and the reform programme had been disrupted by mid-1997. The civil

poor. A large proportion of the labour force in Tajikistan (as high as

confl ict diverted resources to defence and security purposes to the

25%) and Kyrgyzstan depends on work abroad (particularly in Russia),

detriment of other essential needs, and at the same time revenues

remitting a signifi cant volume of income to their home countries.

declined. As of June 1997, the fi scal defi cit reached 10% of GDP, social

safety net payments were eight months in arrears, infl ation exceeded

Tajikistan has experienced strong economic growth since 1997.

60% and the currency depreciated rapidly. Recognising that the reversal

Continued privatisation of medium and large state-owned enterprises