Appendix 2

The Cook Islands--Climate Risk Profile1

Summary

the spatial scale and pervasive nature of weather and

climate. Thus, the likelihood of, say, an extreme

event or climate anomaly is often evaluated for a

The likelihood (i.e., probability) components country, state, small island, or similar geographical

of climate-related risks in the Cook Islands

unit. While the likelihood may well vary within a

are evaluated, for both present-day and

given unit, information is often insufficient to assess

future conditions. Changes into the future

this spatial variability, or the variations are judged

reflect the influence of global warming.

to be of low practical significance.

The risk events for which current and future

The following climate conditions are

likelihoods are evaluated are extreme rainfall events

considered to be potential sources of risk:

(both hourly and daily), drought, high sea levels,

strong winds, and extreme high air temperatures.

·

extreme rainfall events,

Tropical cyclone frequencies over the past century

·

drought,

are also examined. Some climate-related human

·

high sea levels and extreme wave heights,

health and infrastructure risks are also investigated.

·

strong winds, and

Projections of future climate-related risk are

·

extreme high air temperatures.

based on the output of global climate models, for

given emission scenarios and model sensitivity.

Some climate-related human health and

All the likelihood components of projected

infrastructure risks are also investigated.

climate-related risk show marked increases as a

result of global warming.

B.

Methods

A. Introduction

Preparation of a climate risk profile for a given

geographical unit involves an evaluation of current

Formally, risk is the combination of the

likelihoods of all relevant climate-related risks,

consequence of an event and the likelihood (i.e.,

based on observed and other pertinent data.

probability) of that event taking place.

Climate change scenarios are used to develop

While the consequence component of a

projections of how the likelihoods might change in

climate-related risk will be site or sector specific, in

the future. For rainfall and temperature projections,

general the likelihood component of a climate-

the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and

related risk will be applicable over a larger

Industrial Research Organization global climate

geographical area and many sectors. This is due to

model (GCM) was used, as it is considered to work

best in the South Pacific. For drought, strong winds,

and sea level, the Canadian GCM was used to

1 At this time the profile is limited to Rarotonga.

132

Climate Proofing: A Risk-based Approach to Adaptation

develop the projections, as this was the only GCM

envelope of projected emissions, and hence of

for which the required data were available.

greenhouse gas concentrations. For drought, both

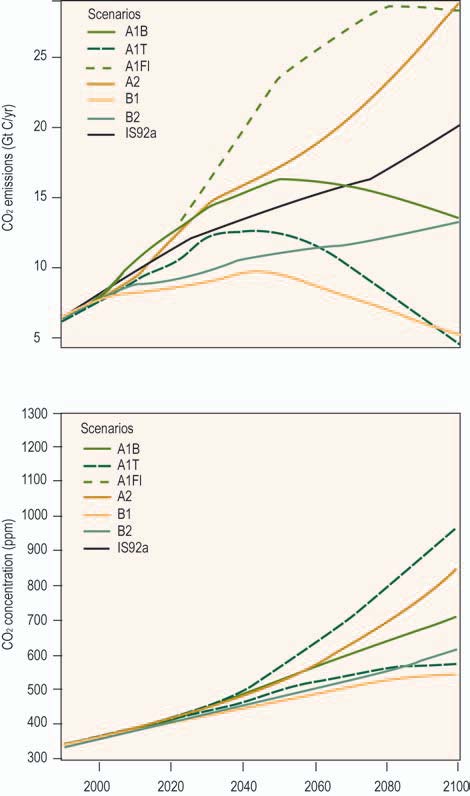

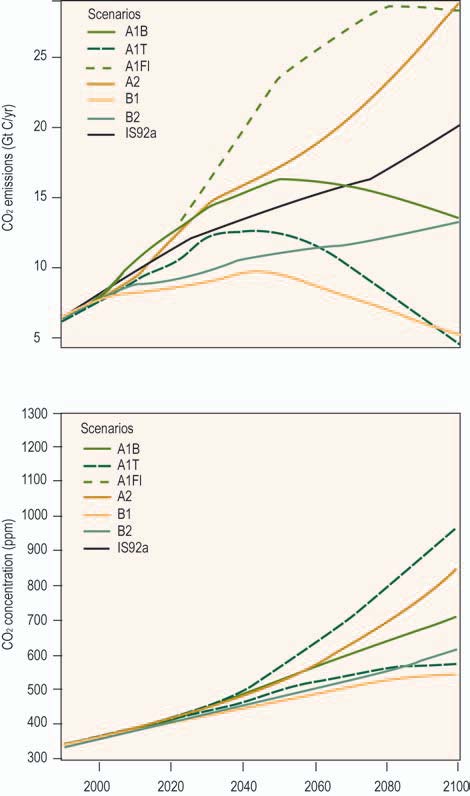

The SRES A1B greenhouse gas emission

the A2 and B2 emission scenarios were used, while

scenario was used when preparing rainfall,

for extreme wind gusts, only the A2 scenario was

temperature, and sea-level projections. Figure A2.1

used. Again, the required projections were available

shows that this scenario is close to the middle of the

only for these scenarios.

C.

Information Sources

Figure A2.1. Scenarios of CO Gas Emissions

2

and Consequent Atmospheric Concentrations

of CO

Daily and hourly rainfall, daily temperature, and

2

hourly wind data were obtained through the Cook

Islands Meteorological Service Office. Sea-level data

for Rarotonga were supplied by the National Tidal

Facility, The Flinders University of South Australia,

(a) CO emmisions

2

and are copyright reserved.

D. Uncertainties

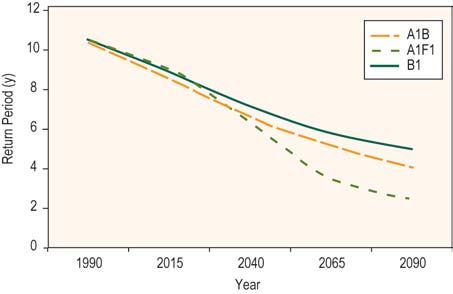

Sources of uncertainty in projections of the

likelihood components of climate-related risks are

numerous. These include uncertainties in greenhouse

gas emissions and those arising from modelling the

complex interactions and responses of the

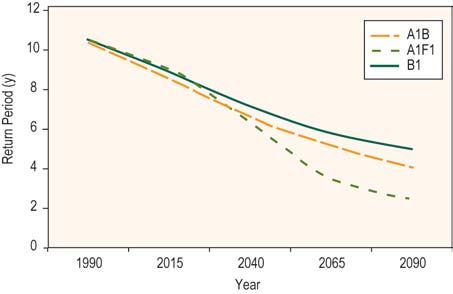

atmospheric and ocean systems. Figure A2.2 shows

how uncertainties in greenhouse gas emissions

impact on estimates of the return periods of a daily

precipitation of at least 250 mm for Rarotonga.

Similar graphs can be prepared for other GCMs

(b) CO concentrations

2

and extreme events, but are not shown here. Policy

and decision makers need to be cognizant of

uncertainties in projections of the likelihood

components of extreme events.

E.

Graphical Presentations

Many of the graphs that follow portray the

likelihood of a given extreme event as a function of

a time horizon. This is the most appropriate and

useful way in which to depict risk, since design life

(i.e., time horizon) varies depending on the nature

of the infrastructure or other development project.

Notes: CO = carbon dioxide; Gt C/yr = gigatonnes of carbon per year.

2

Source: IPCC 2001.

Appendix 2

133

F.

Extreme Rainfall Events

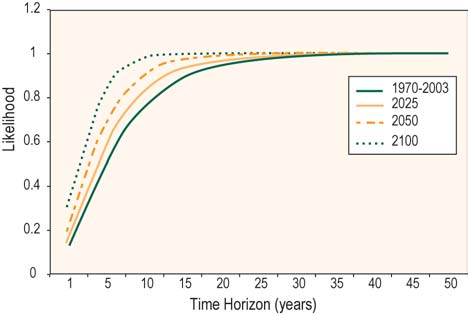

Figure 2.2. Return Periods for Daily Rainfall

of 200 mm in Rarotonga for Given

Daily Rainfall

Greenhouse Gas Emission Scenarios

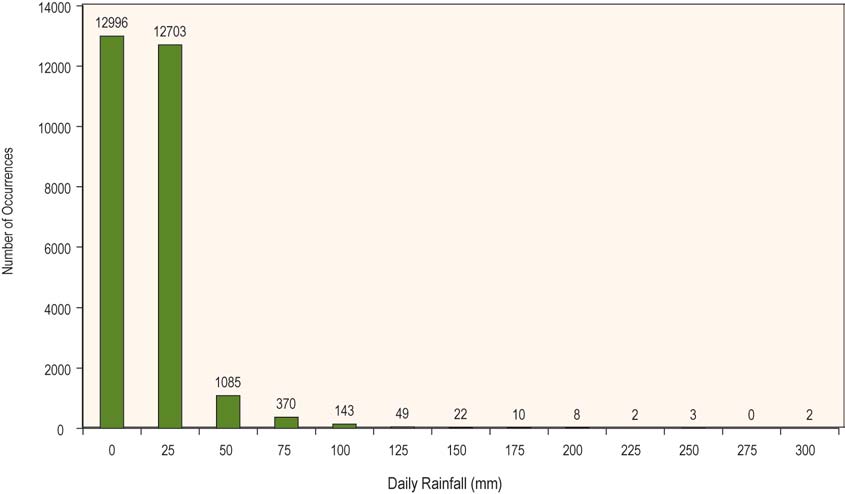

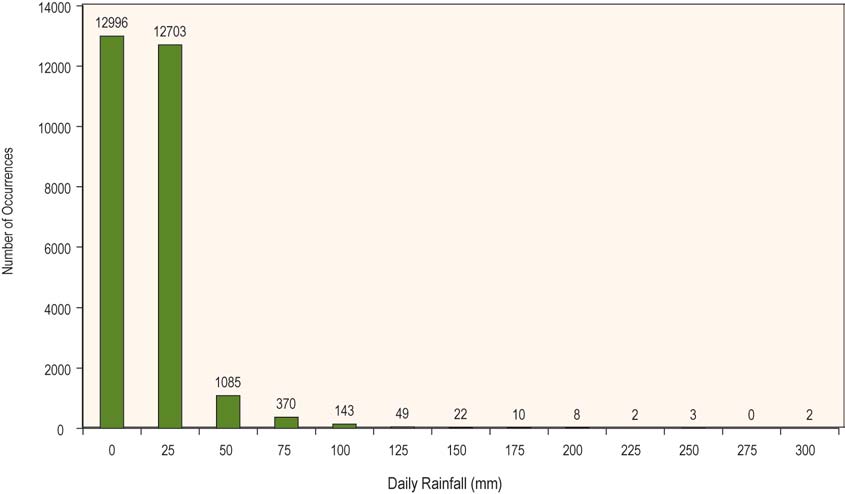

Figure A2.3 shows the frequency distribution of

daily precipitation for Rarotonga. A daily total above

200 millimeters (mm) is a relatively rare event, with

a return period (i.e., recurrence interval) of 11 years.

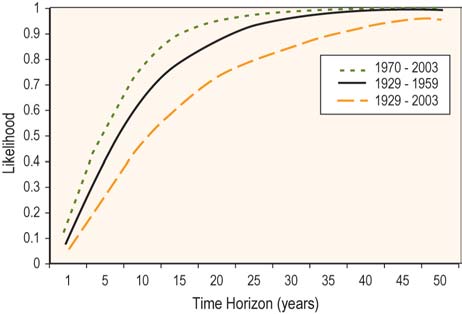

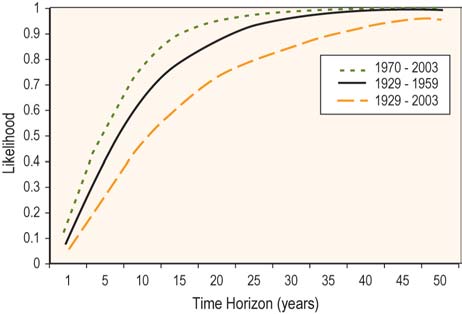

Figure A2.4 shows the likelihood of such an

extreme rainfall event occurring in Rarotonga within

a given time horizon ranging from 1 to 50 years.

It is clear that the frequency of extreme rainfall

events has increased markedly since 1929, when

records began.

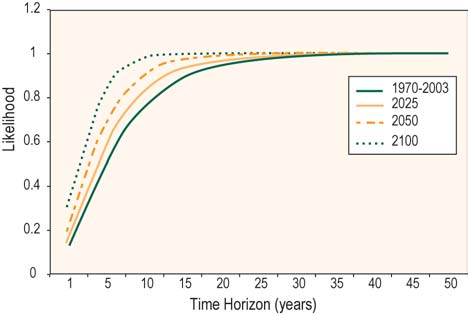

As shown in Table A2.1, global warming will

significantly alter the return periods, and hence the

likelihoods, of the extreme rainfall events. For

Note: Calculations used Hadley Center global climate model (GCM) with Best

example, Figure A2.5 illustrates how the likelihood

Judgment of Sensitivity.

of a daily rainfall of 200 mm will increase over the

Source: CCAIRR findings.

remainder of the present century.

Figure A2.3. Frequency Distribution of Daily Precipitation for Rarotonga

(19292003)

Note: The values above the bars represent the number of occurrences, for the given data interval.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

134

Climate Proofing: A Risk-based Approach to Adaptation

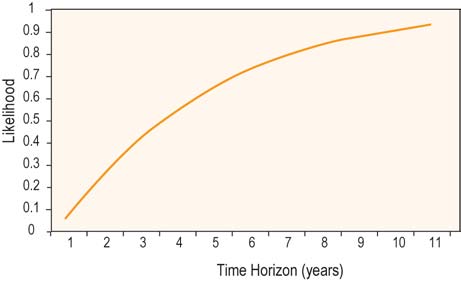

Figure A2.4. Likelihood of a Daily Rainfall

Figure A2.5. Likelihood of a Daily Rainfall

of at Least 200 mm Occurring within the

of at Least 200 mm Occurring within the

Time Horizon

Indicated Time Horizon

(years)

(years)

Note: 0 = zero chance; 1 = statistical certainty. Data for Rarotonga, for

indicated data periods.

Note: 0 = zero chance; 1 = statistical certainty. Data for Rarotonga.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

Table A2.1: Return Periods and Likelihood of Occurrence in 1 Year1 for Daily Rainfall in Rarotonga

Rainfall

Present

(mm)

(19702003)

2025

2050

2100

(at least)

RP

LO

RP

LO

RP

LO

RP

LO

100

1

0.78

1

.81

1

0.83

1

0.87

150

3

0.34

3

.38

2

0.44

2

0.56

200

7

0.14

6

.16

5

0.20

3

0.31

250

18

0.06

13

.08

10

0.10

6

0.17

300

38

0.03

26

.04

19

0.05

11

0.09

350

76

0.01

47

.02

35

0.03

19

0.05

400

141

0.01

81

.01

59

0.02

31

0.03

450

248

0

130

.01

95

0.01

50

0.02

500

417

0

201

0

148

0.01

78

0.01

Notes: RP = return period; LO = likelihood of occurrence.

1 A likelihood of 0 equals zero chance while a likelihood of 1 equates to a statistical certainty that the event will occur within a year.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

Appendix 2

135

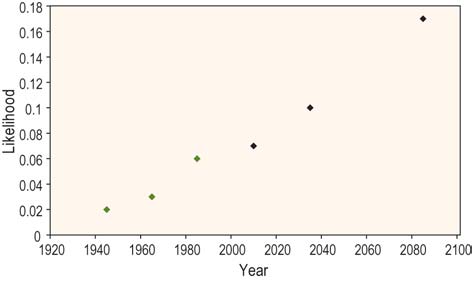

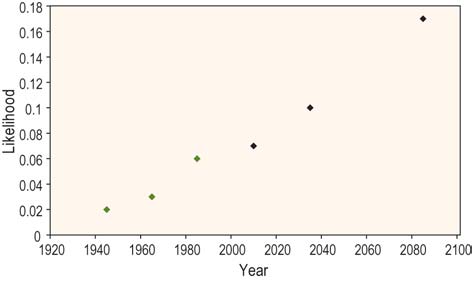

An obvious question arises: are the past changes

in the probability component consistent with the

Figure A2.6. Observed and Projected Likelihoods

changes projected to occur in the future as a result

of a Daily Rainfall of at Least 250 mm

of global warming? The trend of increasing likelihood

Occurring in a Year

that was apparent in the historical data for much of

the last century is projected to continue, in a

consistent manner, through the present century.

Observed and projected likelihoods of at least 250

mm of rain falling in a day are presented in Figure

A2.6. A high degree of consistency is apparent. It is

important to note that this consistency does not

prove the existence of a global warming signal in the

observed data. More detailed analyses are required

before any such attributions can be made.

F.

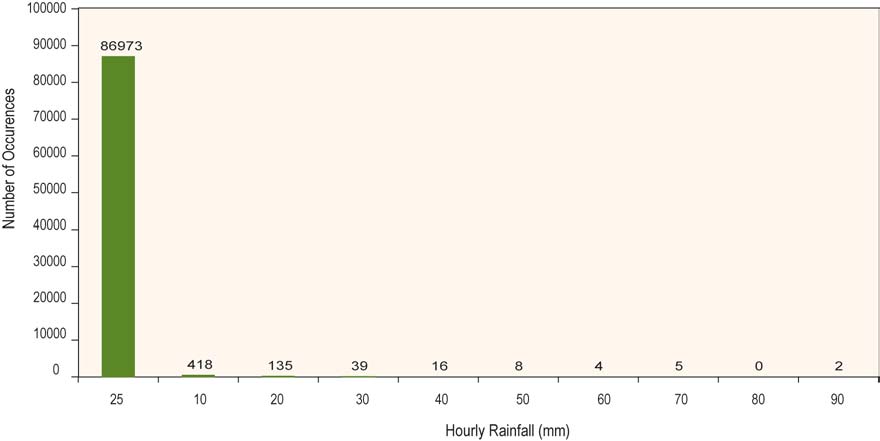

Hourly Rainfall

Notes: black symbols = observed likelihoods; green symbols = projected

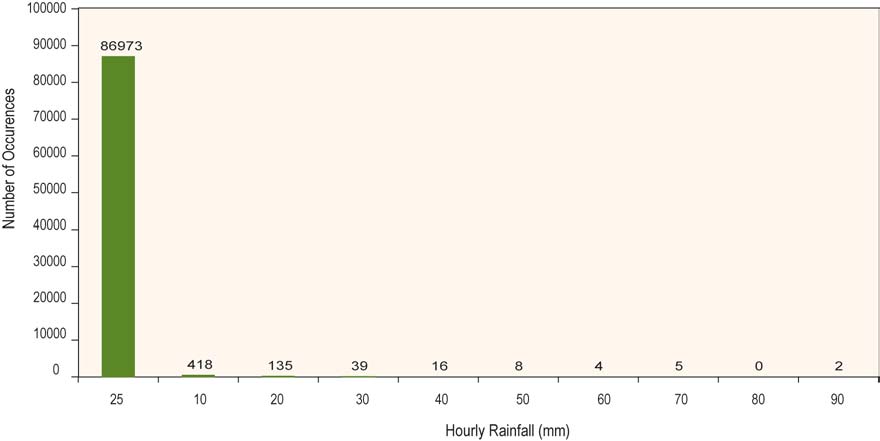

Figure A2.7 shows the frequency distribution of

likelihoods. Data for Rarotonga.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

hourly precipitation for Rarotonga. An hourly total

above 50 mm is a relatively rare event. Table A2.2 shows

such a rainfall has a return period of 3 years, and that

global warming will have a significant impact on the

return periods of extreme rainfall events.

Figure A2.7. Frequency Distribution of Hourly Precipitation for Rarotonga

Notes: Data for 19701979. The values above the bars represent the number of occurrences for the given data interval.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

136

Climate Proofing: A Risk-based Approach to Adaptation

Table A2.2: Return Periods and Likelihood of Occurrence in 1 Year for Daily Rainfall Rarotonga

Rainfall (mm)

Present

2025

2050

2100

(at least)

RP

LO

RP

LO

RP

LO

RP

LO

25

1

0.93

1

0.92

1

0.93

1

0.93

50

3

0.29

3

0.36

3

0.39

2

0.45

75

18

0.05

12

0.08

8

0.12

6

0.18

100

91

0.01

57

0.02

25

0.04

13

0.08

125

384

0

246

0

67

0.01

25

0.04

150

N/A

N/A

980

0

159

0.01

46

0.02

Notes: RP = return period in years; LO = likelihood of occurrence.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

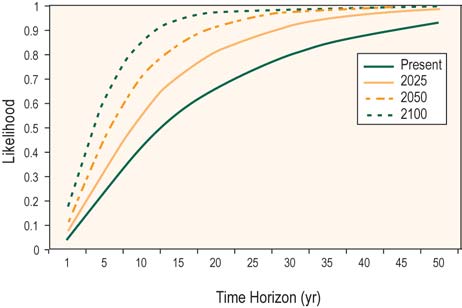

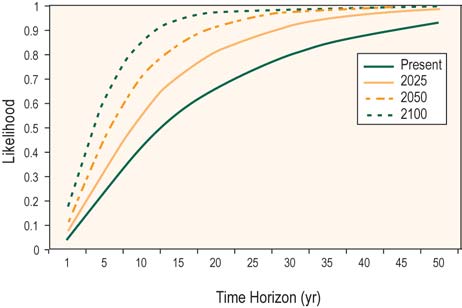

Figure A2.8 depicts the impact of global

F.

Drought

warming on the likelihood of an hourly rainfall of

75 mm for Rarotonga.

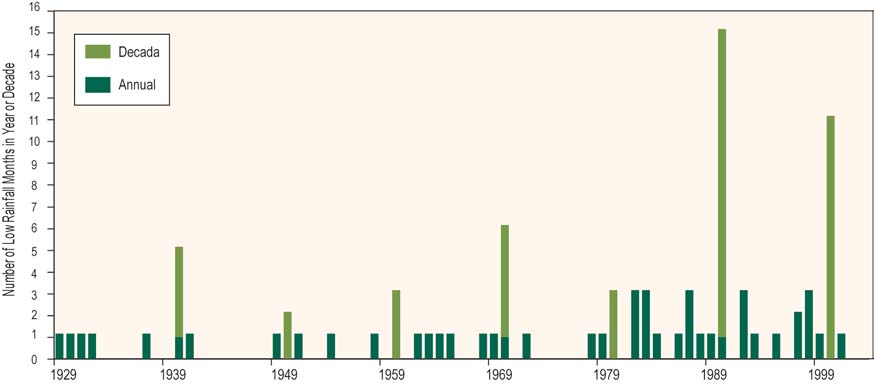

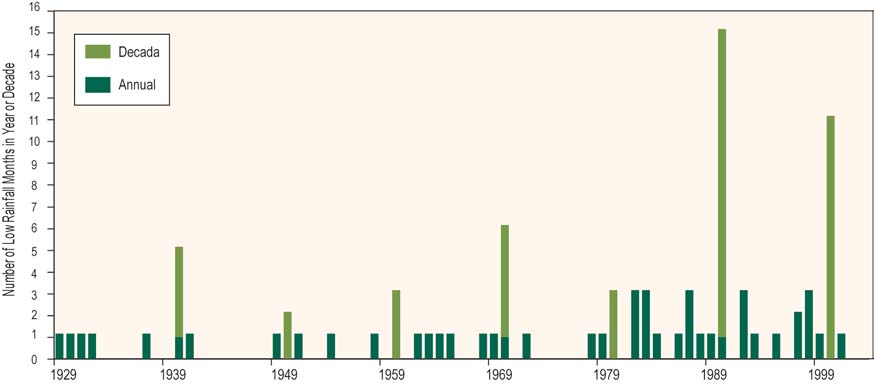

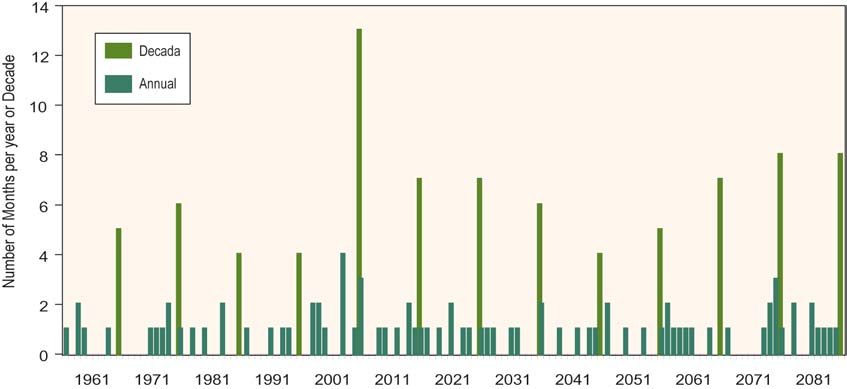

Figure A2.9 presents, for Rarotonga, the number

of months in each year (19292003) and each decade

for which the observed precipitation was below the

10th percentile. Monthly rainfall below the fifth

Figure A2.8. Likelihood of an Hourly Rainfall

percentile is used here as an indicator of drought.

of at Least 75 mm Occurring Within the

Most of the low rainfall months are concentrated

Indicated Time Horizon in Rarotonga

in the latter part of the period of observation,

(years)

indicating that the frequency of drought has

increased since the 1930s. The years with a high

number of months below the fifth percentile

coincide with El Niņo Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

events.

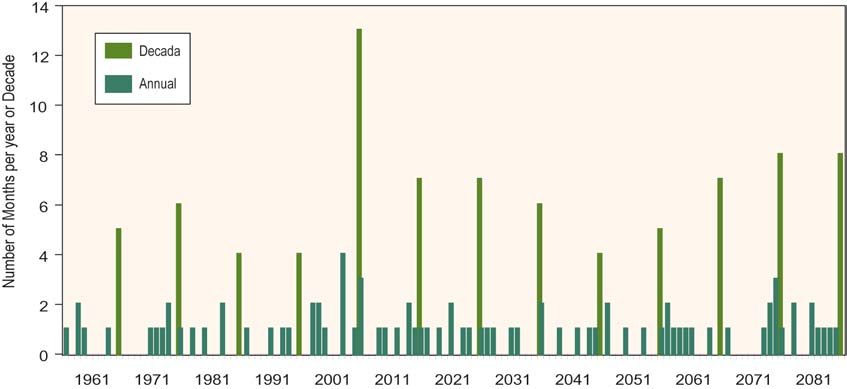

Figure A2.10 shows the results of a similar

analysis, but for rainfall estimates (19611990) and

projections (19912100).

The results indicate that prolonged and more

intense periods of drought will occur during the

remainder of the 21st century.

Notes: Likelihood 0 = zero chance; 1 = statistical certainty. Values for present

day based on observed data for 19802002, with gaps.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

Appendix 2

137

Figure A2.9. Number of Months in Each Year and Decade for which the

Precipitation was Below the Fifth Percentile

Note: data for Rarotonga.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

Figure A2.10. Number of Months Per Year and Per Decade for Which Precipitation in

Rarotonga was Observed, and is Projected to Be, Below the Fifth Percentile

Notes: data from the Canadian global climate module (GCM), with A2 emission scenarios and best estimate for GCM sensitivity.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

138

Climate Proofing: A Risk-based Approach to Adaptation

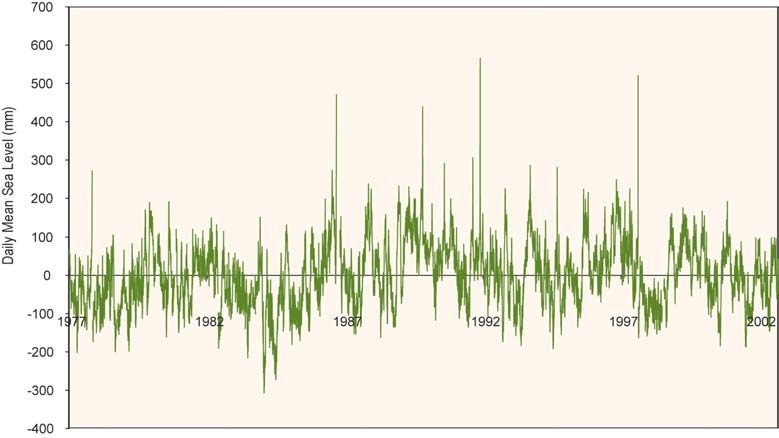

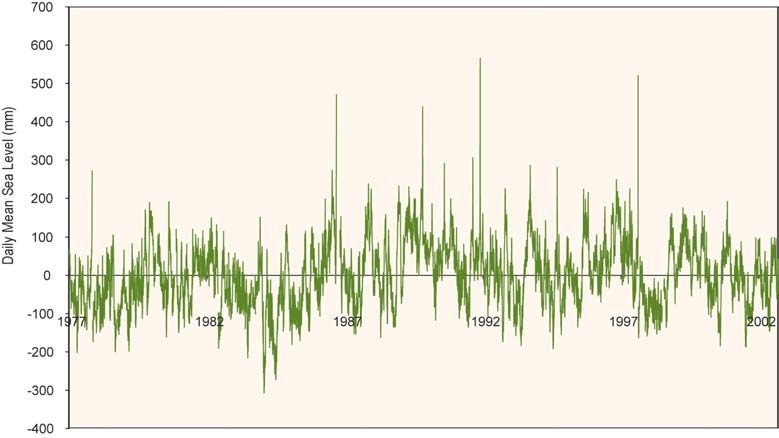

G. High Sea Levels and Extreme

Even more extreme high sea levels occur for

Wave Heights

time scales less than a day. Table A2.3 provides

return periods for given significant on-shore wave

Figure A2.11 shows daily mean values of sea level

heights for Rarotonga, for the present day and

for Rarotonga, relative to mean sea level. Large

projected future. The latter projections are based on

interannual variability occurs in sea level. The

the Canadian GCM 1 GS and the A1B emission

exceptionally high sea levels shown in Figure A2.11 are

scenario.

all associated with the occurrence of tropical cyclones.

Figure A2.11. Daily Mean Values of Sea Level for Rarotonga

(19772002)

Source: CCAIRR findings.

Table A2.3. Return Periods for Significant On-shore Wave Heights, Rarotonga

(years)

Sea Level (m)

Present Day

2025

2050

2100

(at least)

RP

LO

RP

LO

RP

LO

RP

LO

2

2

0.51

2

0.59

2

0.65

1

0.75

4

4

0.25

3

0.31

3

0.35

2

0.45

6

10

0.10

8

0.13

7

0.15

5

0.21

8

30

0.03

23

0.04

18

0.05

12

0.08

10

112

0.01

80

0.01

62

0.02

39

0.03

12

524

0

349

0

258

0

149

0.01

Notes: LO = likelihood pf occurrence; RP = return period.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

Appendix 2

139

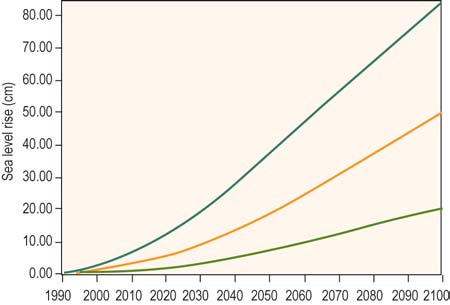

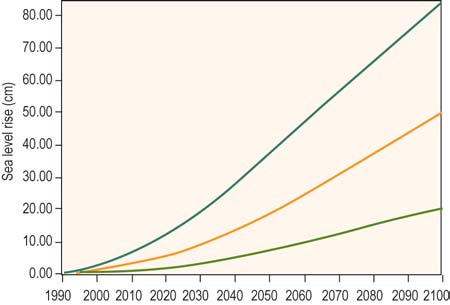

The indicated increases in sea level over the

next century are driven by global and regional

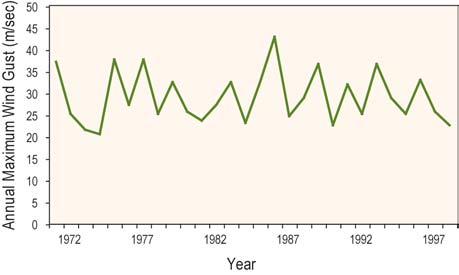

Figure A2.13. Annual Maximum Wind Gust

changes in mean sea level as a consequence of global

Recorded in Rarotonga for the Period

warming. Figure A2.12 illustrates the magnitude of

19721999

this contribution.

Figure A2.12. Sea Level Projections

for Rarotonga

Source: CCAIRR findings.

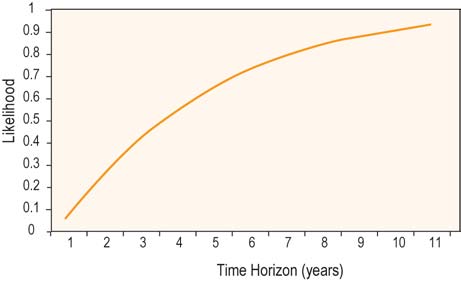

Figure A2.14. Likelihood of a Wind Gust of

40 m/sec (78 kt) Occurring Within the

Indicated Time Horizon, Rarotonga

Notes: Uncertainties related to global climate model sensitivity are indicated

by the blue, red and green lines, representing high, best estimate, and low

sensitivities, respectively.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

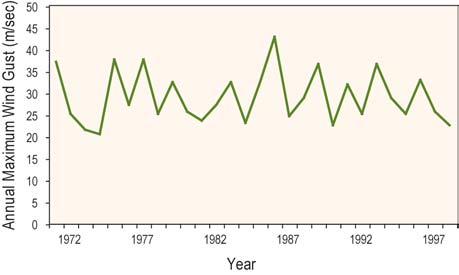

H. Strong Winds

Figure A2.13 shows the annual maximum wind

gust recorded in Rarotonga for the period 19721999.

Figure 2.14 presents the likelihood of a wind

gust of at least 40 m/sec occurring at Rarotonga

within the specified time horizon.

Table A2.4 presents the return periods based on

Notes: 0 = zero chance; 1 = statistical certainty. Data for Rarotonga, Cook

an analysis of the observed maximum hourly wind

Islands (19721999). A wind gust of 40 ms-1 has a return period of 20 years.

gust data and the adjusted GCM wind speed data.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

The return period estimates of Kirk are for open

water conditions. Strong agreement is observed

between these and the return periods based on

to show slightly shorter return periods for lower

observed data, suggesting that the Rarotonga

extreme wind speeds and slightly longer return

anemometer provides extreme gust estimates that

periods for higher extreme wind speeds.

are reasonably representative of open water

Arguably the most important finding arising

conditions.

from this analysis is the suggestion that, over the

Comparison of the return period estimates for

coming 50 years or so, the return periods for the

the 19611990 GCM data with the observed data also

most extreme wind speeds will reduce significantly,

reveals good agreement, though the GCM data tend

decreasing by approximately half by 2050.

140

Climate Proofing: A Risk-based Approach to Adaptation

Table A2.4: Estimates of Return Periods for Given Maximum Wind Speeds, Rarotonga

(years)

Return Period (years)

Wind Speed

Kirk

Observed Data

GCM Based Maximum Wind Speed Data

(m/sec)

(1992)

(19721999)

19611990

19912020

20212050

28.5

2

2

1

1

1

33.9

5

5

2

2

2

37.5

10

11

3

4

4

38.8

13

14

5

5

6

41.9

25

29

18

16

14

44.9

50

57

60

45

31

47.8

100

113

120

95

64

Note: GCM = global climate module.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

I.

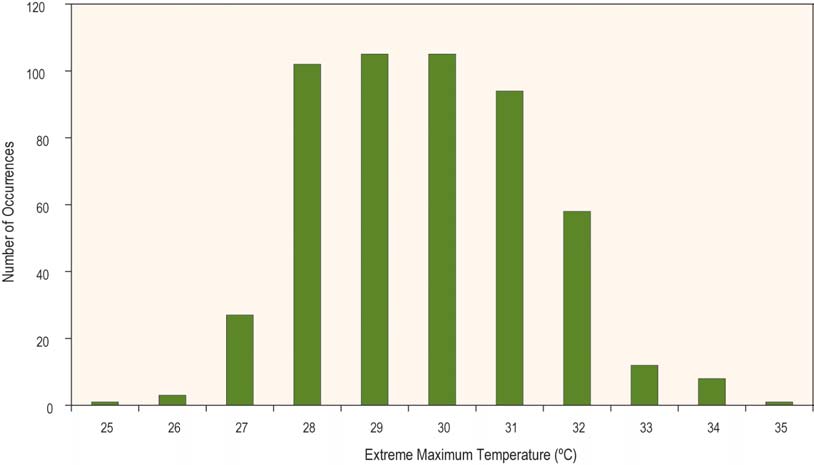

Extreme High Temperatures

maximum temperature for Rarotonga, based on

observed data (19612003) and GCM projections.

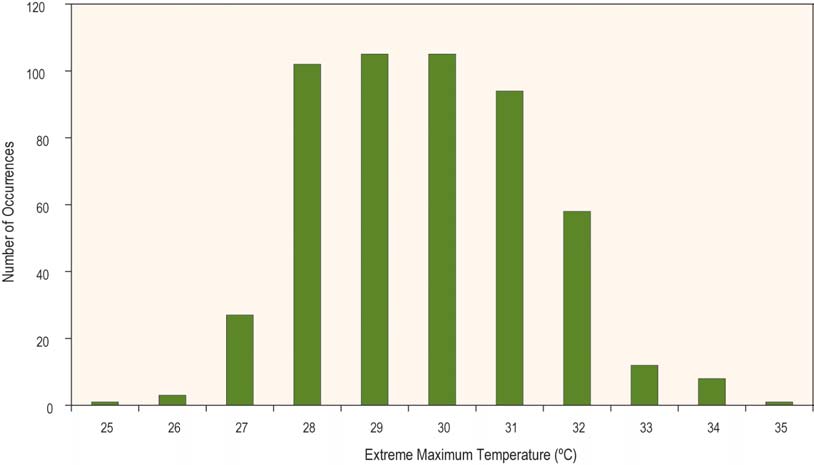

Figure A2.15 presents the frequency distribu-

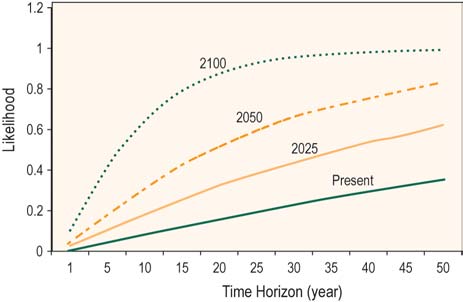

Figure A2.16 shows the likelihood of a

tion of daily maximum temperature for Rarotonga.

maximum temperature of at least 35°C occurring

Table A2.5 details the return periods for daily

within the indicated time horizon.

Figure A2.15. Frequency distribution of Monthly Extreme Maximum Temperature for Rarotonga

Note: Based on observed data from 1961 to 2003.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

Appendix 2

141

Table A2.5. Return Periods for Monthly Extreme Maximum Temperature, Rarotonga

(years)

Maximum

Observed

Projected

Temperature

(oC)

(1961-2003)

2025

2050

2100

RP

LO

RP

LO

RP

LO

RP

LO

31

1

0.72

1

0.90

1

0.97

1

1

32

3

0.33

2

0.54

1

0.71

1

0.94

33

9

0.12

5

0.22

3

0.34

2

0.64

34

29

0.03

14

0.07

9

0.12

3

0.29

35

108

0.01

52

0.02

29

0.03

10

0.10

36

435

0

208

0

115

0.01

37

0.03

Notes: LO = likelihood of occurrence; RP = return period.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

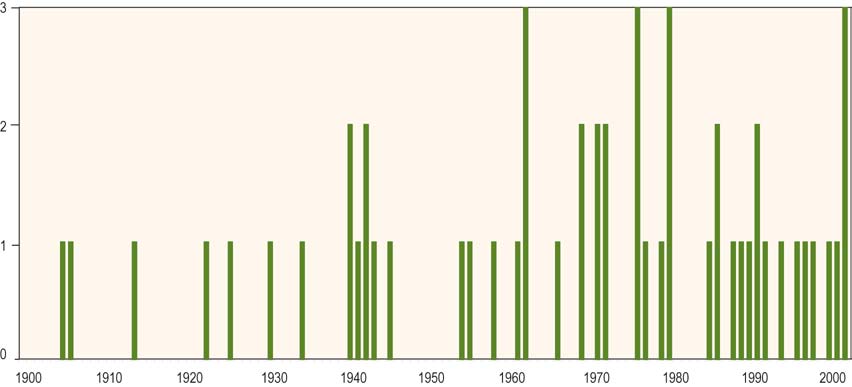

improved substantially over the same time period,

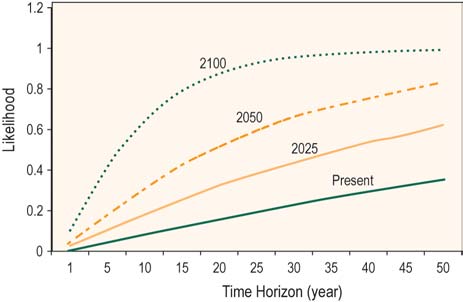

Fig A2.16 Likelihood of a Maximum

it is unwise to read too much into the marked

Temperature of at Least 35°C Occurring Within

contrast in frequency between the first and second

the Indicated Time Horizon in Rarotonga

halves of the 20th century. The record for the last

(years)

few decades is much more reliable, hence the

doubling in decadal frequencies between the 1950s

and 1990s may well be closer to the truth. It is

certainly consistent with the fact, since the 1970s

that El Niņo episodes have tended to be more

frequent, without intervening La Niņa events. The

duration of the 199095 El Niņo is unprecedented

in the climate record of the past 124 years.

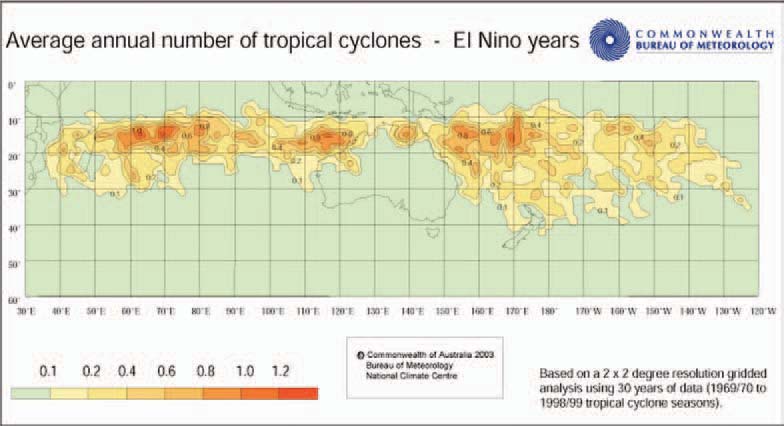

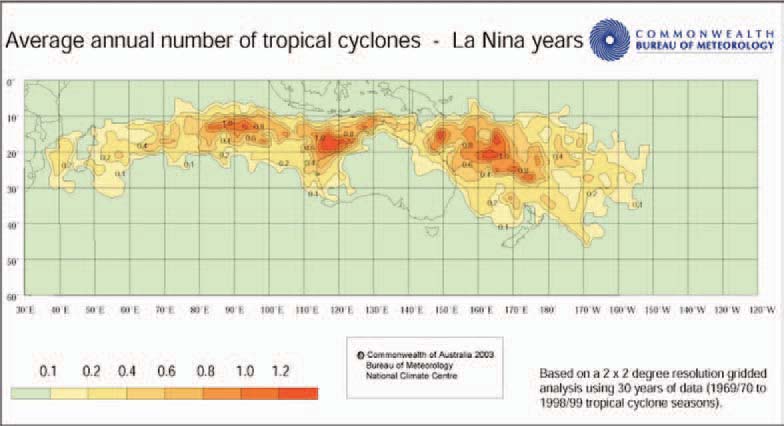

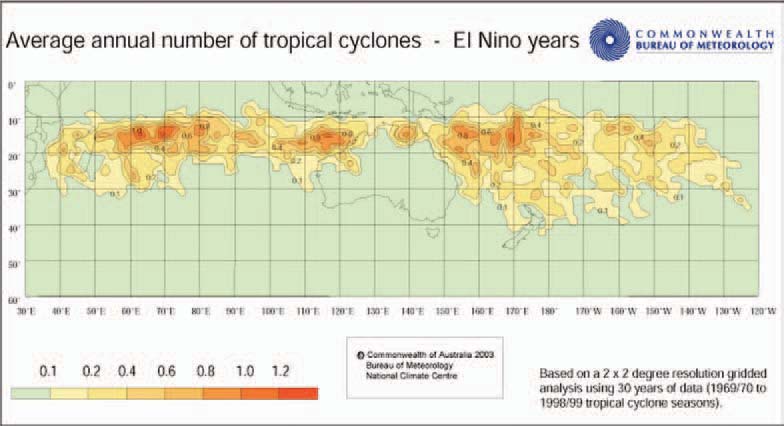

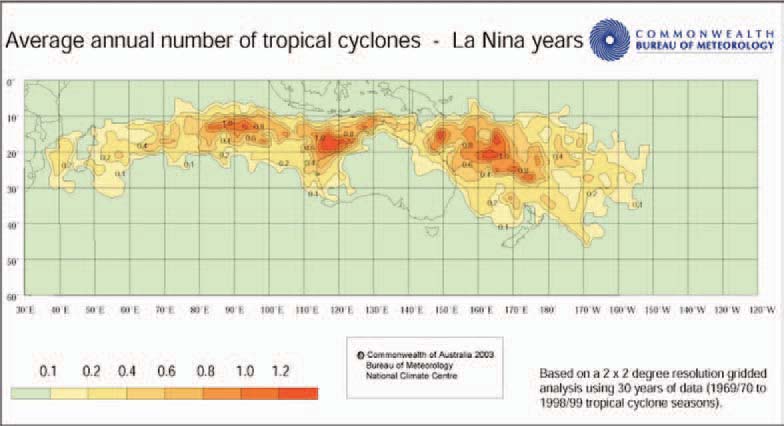

Studies by Australia's Bureau of Meteorology

(Figure A2.18a and b) reveal the consequences of

the weakened trade winds and eastward movement

of the warm waters of the western tropical Pacific

during El Niņo events. Because convective systems

(e.g., thunderstorms and rainstorms) and tropical

cyclones preferentially occur over warmer waters,

Note: 0 = zero chance; 1 = statistical certainty.

Source: CCAIRR findings.

changes in the pattern of sea surface temperatures

is reflected in the distribution of rainfall and tropical

cyclones.

A possible consequence of the increased

J.

Tropical Cyclones

persistence of El Niņo conditions in recent decades

is the apparent intensification of tropical cyclones,

as reflected in the systematic increase in upper 10

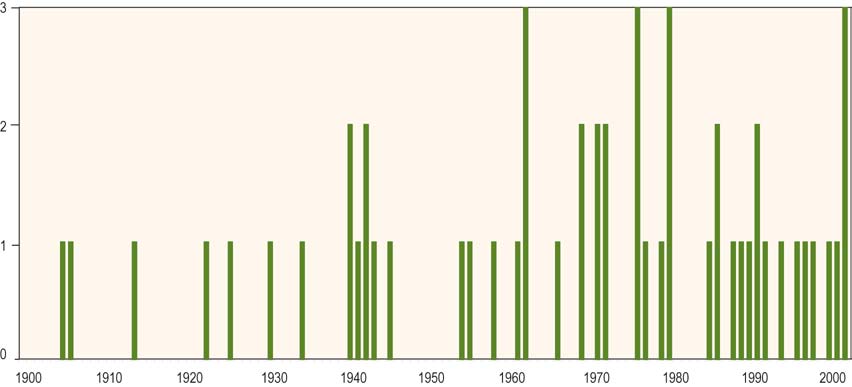

The number of tropical cyclones passing close

percentile heights of open water waves associated

to, and affecting Rarotonga appears to have

with tropical cyclones occurring in the vicinity of

increased during the last century (Figure A2.17).

Rarotonga (Table A2.6).

However, since observing and reporting systems

142

Climate Proofing: A Risk-based Approach to Adaptation

Figure A2.17. Number of Tropical Cyclones per Year passing Close to, and Affecting, Rarotonga

Sources: Kerr 1976, Revell 1981, Thompson et al. 1992, d'Aubert and Nunn 1994, Fiji Meteorological Service 2004, and Ready (personal communication).

Figure A2.18a. Average Annual number of Tropical Cyclones for El Niņo Years

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology, n.d. Reproduced by permission

Appendix 2

143

Figure A2.18b. Average Annual number of Tropical Cyclones for La Niņa Years

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology, n.d. Reproduced by permission

Table A2.6. Open Water Wave Height (Average of Top 10%)

Associated with Tropical Cyclones Recently Affecting Rarotonga

Cyclone

Wave Height

(name and year)

(m)

Charles (1978)

11

Sally (1987)

10

Val (1991)

14

Pam (1997)

14

Dovi (2003)

17

Heta (2004)

17

Nancy (2005)

22

Percy (2005)

19

Source: Dorrell (personal communication).

144

Climate Proofing: A Risk-based Approach to Adaptation