The

Danube River

Basin District

River basin characteristics, impact of human activities and economic analysis required under Article 5, Annex II and Annex III,

and inventory of protected areas required under Article 6, Annex IV of the EU Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC)

Part A Basin-wide overview

Short: "Danube Basin Analysis (WFD Roof Report 2004)"

//// Deutschland //// Österreich //// BosnaiHercegovina////Balgarija////H

//// Slovensko ///

r

/

v

ora

S

a

G

lo

ts

ve

k

n

a

rna

ija

//

i C

//

/

//

/

Ukr

C

aïna ////

e

rbija

ská r

//// S

epub

ânia

lika //// Magyarország////Moldova////Rom

The complete report consists of Part A: Basin-wide overview, and Part B: Detailed analysis of the Danube river basin countries

18 March 2005, Reporting deadline: 22 March 2005

Prepared by

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

(ICPDR) in cooperation with the countries of the Danube River Basin

District.

The Contracting Parties to the Danube River Protection Convention

endorsed this report at the 7th Ordinary Meeting of the ICPDR on

December 13-14, 2004. The final version of the report was approved

18 March 2005.

Overall coordination and editing by Dr. Ursula Schmedtje, Technical

Expert for River Basin Management at the ICPDR Secretariat, under

the guidance of the River Basin Management Expert Group.

ICPDR Document IC/084, 18 March 2005

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

Vienna International Centre D0412

P.O. Box 500

A-1400 Vienna, Austria

Phone: +(43 1) 26060 5738

Fax:

+(43 1) 26060 5895

e-mail: icpdr@unvienna.org

web:

http://www.icpdr.org/DANUBIS

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many people that have contributed to the

Specific text contributions have been provided by:

successful preparation of this report:

Jasmine Bachmann · Horst Behrendt · Sebastian Birk · Pavel Biza ·

the 13 Danube countries and their experts for their comprehensive

Joachim D'Eugenio · Jos van Gils · Johannes Grath · Carmen

data and text contributions, their comments and ideas,

Hamchevici · Wenke Hansen · Eduard Interwies · Eleftheria Kampa ·

the ICPDR River Basin Management Expert Group for the overall

Helga Lindinger · Igor Liska · Liviu Popescu · Mihaela Popovici ·

guidance and coordination of WFD implementation in the Danube

Tanja Pottgiesser · Ursula Schmedtje · Gerhard Sigmund ·

River Basin District,

Mario Sommerhäuser · Stefan Speck · Ilse Stubauer · Birgit Vogel ·

the other ICPDR Expert Groups for giving guidance on specific

Philip Weller · Gerhard Winkelmann-Oei · Alexander Zinke.

WFD issues, and for defining common criteria for basin-wide data

collection,

The maps have been produced by Ulrich Schwarz.

the consultants for drafting chapters and giving their expertise on

Danube issues,

the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project for technical and

financial support, and

the ICPDR Secretariat for the preparation of the Roof Report,

coordination and harmonisation of contributions, and editing to

create an informative and readable report.

This report was coordinated and edited by Ursula Schmedtje.

Technical support was given by Edith Hödl.

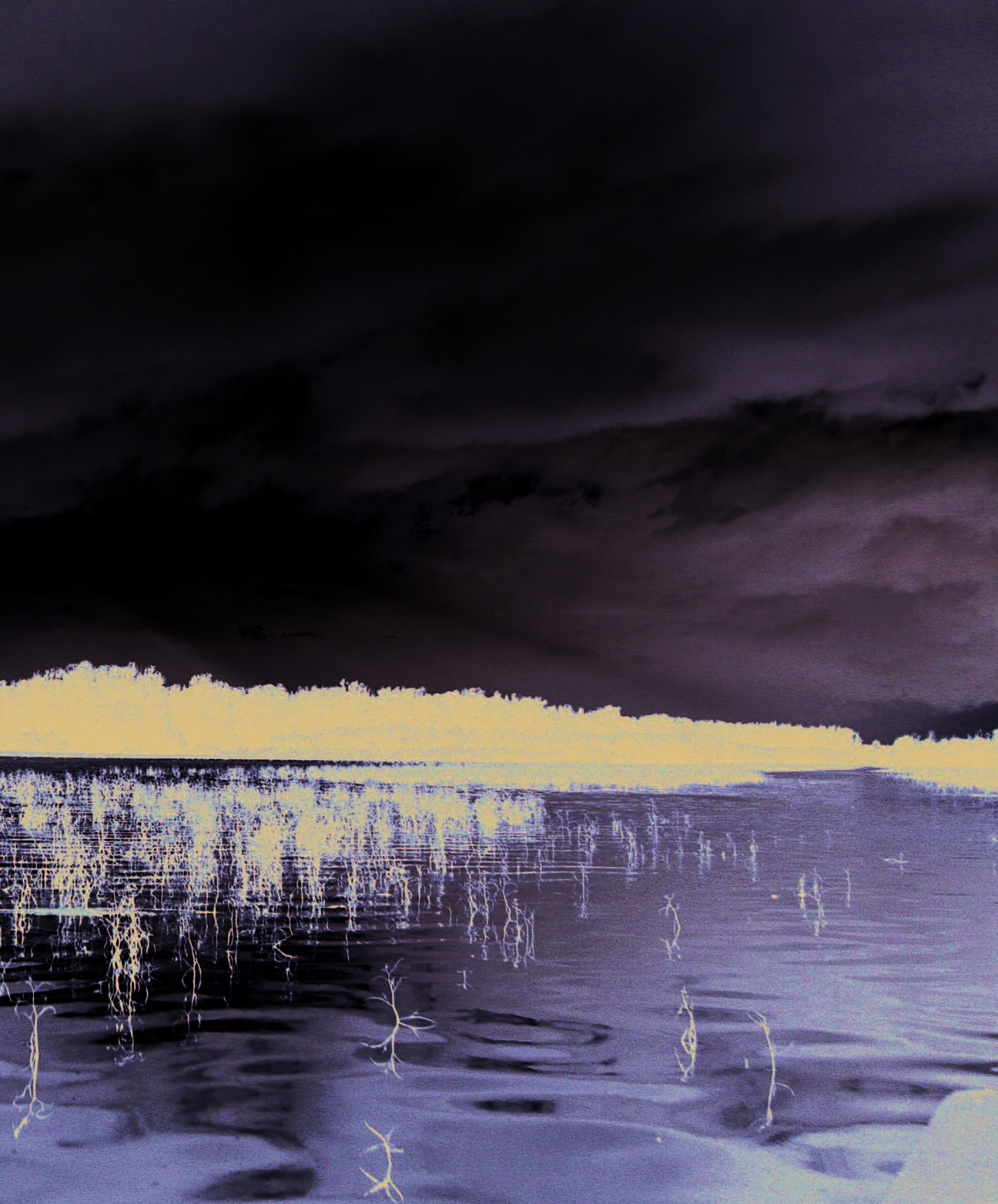

Mario Romulic, Croatia

Table of Contents

Analyses required under Article 5, Annex II and Annex III, and Inventory required under Article 6, Annex IV WFD

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Aim of the report

12

1.2. Structure and contents of the report

12

1.3. Status of the report and disclaimer

16

2. THE DANUBE RIVER BASIN DISTRICT AND ITS INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION ARRANGEMENTS

2.1. Delineation of the Danube River Basin District

18

2.2. States in the Danube River Basin District

20

2.3. International coordination of WFD implementation

22

2.3.1. Coordination at the basin-wide level

22

2.3.2. Bilateral and multilateral

24

2.3.3. Competent authorities

25

3. GENERAL CHARACTERISATION OF THE DANUBE RIVER BASIN DISTRICT

3.1. Geographic characterisation

26

3.2. Climate and hydrology

26

3.3. The Danube River and its main tributaries

28

3.4. Important lakes in the Danube River Basin District

30

3.5. Major wetlands in the Danube River Basin District

32

3.6. Important canals for navigation

33

3.7. Groundwater in the Danube River Basin District

35

4. CHARACTERISATION OF SURFACE WATERS (ART. 5 AND ANNEX II)

4.1. Identification of surface water categories

36

4.2. Surface water types and reference conditions

36

4.2.1. Ecoregions in the Danube River Basin District

36

4.2.2. Rivers

38

4.2.2.1. Typology of the Danube River

38

4.2.2.2. Typology of the tributaries in the Danube River Basin District

39

4.2.2.3. Reference conditions

41

4.2.3. Lakes

44

4.2.3.1. Lake types

44

4.2.3.2. Reference conditions

45

4.2.4. Transitional waters

45

4.2.5. Coastal waters

47

4.3. Identification of surface water bodies

48

4.3.1. Water bodies in rivers

48

4.3.2. Water bodies in lakes

48

4.3.3. Water bodies in transitional and coastal waters

49

4.3.4. Heavily modified water bodies (provisional identification)

49

4.3.5. Artificial water bodies

49

4.4. Identification of significant pressures

51

4.4.1. Significant point source pollution (overview)

52

4.4.1.1. Data availability

52

4.4.1.2. Contribution of sub-basins to the total point source pollution of the Danube

54

Table of Contents 2

4.4.2. Significant sources of nutrients (point and diffuse) including land use patterns

57

4.4.2.1. Introduction

57

4.4.2.2. Present state of the nutrient point discharges

57

4.4.2.3. Land use patterns and agricultural indicators

58

4.4.2.4. Diffuse nutrient pollution

66

4.4.2.5. Historical development of the diffuse source nutrient pollution into the Danube River system

71

4.4.3. Other significant diffuse source pollution

72

4.4.3.1. Analysis of priority pesticides used in the Danube River Basin District

73

4.4.4. Significant hydromorphological alterations

74

4.4.4.1. Hydropower generation

75

4.4.4.2. Flood defence measures

77

4.4.4.3. Navigation

78

4.4.4.4. Water transfer and diversion

79

4.4.4.5. Future infrastructure projects

79

4.4.5. Other significant anthropogenic pressures

80

4.4.5.1. Accident Pollution

80

4.4.5.2. Fisheries

82

4.4.5.3. Invasive species

82

4.5. Assessment of impacts on the basin-wide level

84

4.5.1. Impacts on rivers

86

4.5.1.1. Impacts from organic pollution

86

4.5.1.2. Contamination with hazardous substances

93

4.5.1.3. Impacts from nutrient loads

100

4.5.1.4. Impacts caused by hydromorphological alterations

109

4.5.1.5. Impacts from over-fishing

113

4.5.2. Impacts on lakes and lagoons

115

4.5.2.1. Neusiedlersee / Ferto-tó

115

4.5.2.2. Lake Balaton

115

4.5.2.3. Ozero Ialpug

116

4.5.2.4. Razim-Sinoe lacustrine system

116

4.5.3. Impacts on the Danube Delta

117

4.5.3.1. Link to pressures

117

4.5.3.2. Impact assessment

118

4.5.3.3. Expected future developments

118

4.5.4. Impacts on coastal waters and the wider marine environment of the Black Sea

119

4.5.4.1. Assessment of status and impact

119

4.5.4.2. Impact assessment

120

4.5.4.3. Expected future developments

124

4.5.5. Impacts on artificial water bodies

124

4.5.5.1. Main-Danube Canal

124

4.5.5.2. Danube-Tisza-Danube Canal System

124

4.5.5.3. Danube-Black Sea Canal

124

4.6. Heavily modified surface waters (provisional identification)

125

4.6.1. Provisionally identified heavily modified waters on rivers

125

4.6.1.1. Approach for selecting heavily modified water bodies for the basin-wide overview

125

4.6.1.2. Provisional identification of heavily modified waters on rivers based on the agreed criteria

125

4.6.2. Provisional HMWBs on lakes

129

4.6.3. Provisional HMWBs on transitional and coastal waters

129

Table of Contents 3

4.7. Risk of failure to reach the environmental objectives (overview)

130

4.7.1. Approach for the risk assessment on surface waters

130

4.7.2. Risk of failure analysis on rivers

132

4.7.2.1. Results on the Danube River

133

4.7.2.2. Results on the Danube tributaries

134

4.7.2.3. Discussion of results of the risk analysis on rivers

135

4.7.3. Risk of failure analysis on lakes

135

4.7.4. Risk of failure analysis on transitional and coastal waters

136

4.7.5. Risk of failure analysis on heavily modified water bodies

136

4.7.6. Risk of failure analysis on artificial water bodies

136

4.8. Data gaps and uncertainties

137

4.8.1. Typology of surface waters and definition of reference conditions

137

4.8.2. Significant pressures relevant on the basin-wide scale

137

4.8.3. Assessment of impacts on the basin-wide level

139

4.9. Conclusions on surface waters

141

4.9.1. Surface water types and reference conditions

141

4.9.2. Significant point and diffuse sources of pollution

141

4.9.3. Impacts from organic pollution

142

4.9.4. Contamination with hazardous substances

143

4.9.5. Impacts from nutrients

143

4.9.6. Impacts on the Danube Delta

144

4.9.7. Coastal waters and the wider marine environment of the Black Sea

144

4.9.8. Hydromorphological alterations

145

4.9.9. Important heavily modified surface waters

145

4.9.10. Invasive species

146

4.9.11. Risk of failure analysis

146

5. CHARACTERISATION OF GROUNDWATERS (ART. 5 AND ANNEX II)

147

5.1. Location, boundaries and characterisation of groundwater bodies

148

5.1.1. Important transboundary groundwater bodies in the Danube River Basin District

149

5.1.2. Summary description of the important transboundary groundwater bodies

151

5.2. Risk of failure to reach the environmental objectives (overview)

152

5.2.1. Approach for the risk of failure analysis on groundwater

152

5.2.2. Results of the risk analysis on groundwater

152

5.3. Data gaps and uncertainties

153

5.4. Conclusions on groundwater

153

6. INVENTORIES OF PROTECTED AREAS (ART. 6 AND ANNEX IV)

154

6.1. Inventory of protected areas for species and habitat protection

154

6.1.1. Approach for setting up the inventory

155

6.1.2. Definition of important water-related protected areas on the basin-wide scale

155

6.1.3. Establishment of the inventory with a core data set

155

6.2. Data gaps and uncertainties

156

6.3. Conclusions on protected areas

156

Table of Contents 4

7. ECONOMIC ANALYSIS (ART. 5 AND ANNEX III)

157

7.1. Economic analysis of water uses (overview)

157

7.1.1. Assessing the economic importance of water uses

157

7.1.1.1. Characteristics of water services

161

7.1.1.2. Characteristics of water uses

163

7.1.2. Projecting trends in key economic indicators and drivers up to 2015

163

7.1.3. Assessing current levels of recovery of the costs of water services

165

7.1.4. Preparing for the cost-effectiveness analysis

165

7.2. Data gaps and uncertainties

165

7.3. Conclusions on the economic analysis of water uses

165

8. PUBLIC INFORMATION AND CONSULTATION

166

8.1. Strategy for public participation in river basin management 2003-2009

166

8.2. ICPDR Operational Plan

167

8.2.1. Activities in 2004

167

8.2.1.1. Joining forces a Network of Public Participation Focal Points

167

8.2.1.2. Confidence building WFD brochure and WFD on the internet

167

8.2.1.3. Reaching the public developing a media network

167

8.2.1.4. Knowing your partners a stakeholder analysis

167

8.2.2. Celebrating the Danube River Basin Danube Day

168

9. KEY CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

169

10. REFERENCES

172

5

List of Tables

TABLE 1

Issues covered in Part A (Roof report) and Part B (National reports)

15

TABLE 2

Area of the Danube River Basin District

18

TABLE 3

States in the Danube River Basin District

20

TABLE 4

Coverage of the states in the Danube River Basin (DRB) and estimated population

21

TABLE 5

Overview of bilateral agreements and bilateral cooperations for WFD implementation in the Danube River Basin District

24

TABLE 6

List of competent authorities in the Danube River Basin District

25

TABLE 7

The Danube and its main tributaries (1st order tributaries with catchments > 4,000 km2) in the order of their confluence with the

Danube from the source to the mouth

29

TABLE 8

The main lakes (with a surface area > 100 km2) in the Danube River Basin

31

TABLE 9

Hydrological characteristics of DBSC and PAMNC

34

TABLE 10

Ecoregions in the Danube River Basin

37

TABLE 11

Definition of Danube section types

38

TABLE 12

Obligatory factors used in river typologies (System A and B)

40

TABLE 13

Optional factors used in river typologies by countries using System B

41

TABLE 14

Number of stream types defined on the DRBD overview level

42

TABLE 15

Basic criteria for defining reference conditions (harmonised basin-wide)

43

TABLE 16

Lakes selected for the basin-wide overview and their types

44

TABLE 17

Quality elements used to describe reference conditions of lakes

45

TABLE 18

Types of transitional waters in the Danube River Basin District

47

TABLE 19

Types of coastal waters in the Danube River Basin District

47

TABLE 20

Number of water bodies on rivers on the DRBD overview scale

48

TABLE 21

Criteria for the delineation of water bodies in rivers

48

TABLE 22

Transitional water bodies and reasons for their delineation

49

TABLE 23

Coastal water bodies and reasons for their delineation

49

TABLE 24

Artificial water bodies relevant on the basin-wide scale

50

TABLE 25

Definition of significant point source pollution on the basin-wide level

52

TABLE 26

Significant point sources of pollution in the Danube River Basin District according to the criteria defined in Table 25

53

TABLE 27

Municipal, industrial and agricultural point source discharges of COD, BOD, total nitrogen and phosphorus from

significant sources according the criteria of Table 25

55

TABLE 28

Specific point source discharges of COD, BOD, total nitrogen and phosphorus from municipal waste water treatments (WWTPs),

direct industrial discharges, and agricultural point discharges in the sub-catchments of the Danube

56

TABLE 29

Consumption of pesticides (in t/a) in some Danube countries and specific pesticide consumption (kg per ha agricultural area and year)

in the year 2001 according to the FAO database

73

TABLE 30

Classification scheme of water quality according to saprobic index

91

TABLE 31

Annual mean Saprobic Index based on macrozoobenthos (TNMN stations 1997-2000)

92

TABLE 32

Annual mean Saprobic Index based on phytoplankton (TNMN stations 1997-2000)

93

TABLE 33

Fish stocking and catch of sturgeon in Bulgaria in 2001-2003

114

TABLE 34

Matrix of common borders and number of nominated important transboundary groundwater bodies or

groups of groundwater bodies in the DRBD

149

TABLE 35

Nominated important transboundary groundwater bodies or groups of groundwater bodies in the DRBD

150

TABLE 36

General socio-economic indicators

158

TABLE 37

Water production, wastewater services and connection rates

159

TABLE 38

Wastewater treatment plants

160

TABLE 39

Population connected to wastewater treatment plants data refers to whole country

161

TABLE 40

Production of main economic sectors

161

List of Tables 6

TABLE 41

Electricity generation in the DRB: total and electricity generation devided by origin

162

TABLE 42

Inland navigation

165

TABLE 43

National trends in total water supply and demand up to 2015

164

TABLE 44

National economic growth rates for main economic sectors (up to 2015)

164

7

List of Figures

FIGURE 1

Structure of the report for the Danube River Basin District

13

FIGURE 2

Organisational structure under the Danube River Protection Convention

22

FIGURE 3

Coordination mechanisms for WFD implementation in the Danube River Basin (for bilateral agreements only some examples are shown;

a full list is contained in Table 5)

23

FIGURE 4

Location of the Danube River Basin in Europe

27

FIGURE 5

Longitudinal profile of the Danube River and contribution of water from each country (in %) to the cumulative discharge of the Danube

(in Mio m3/year), based on data for 1994-1997 using the Danube Water Quality Model

28

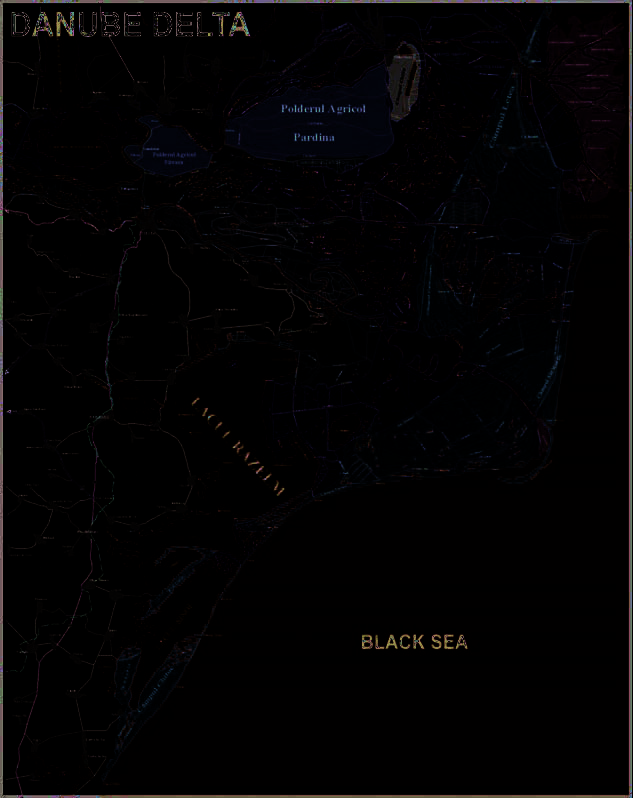

FIGURE 6

The Danube Delta

33

FIGURE 7

Ecoregions covered by the Danube River Basin District

37

FIGURE 8

Danube section types; the dividing lines refer only to the Danube River itself

39

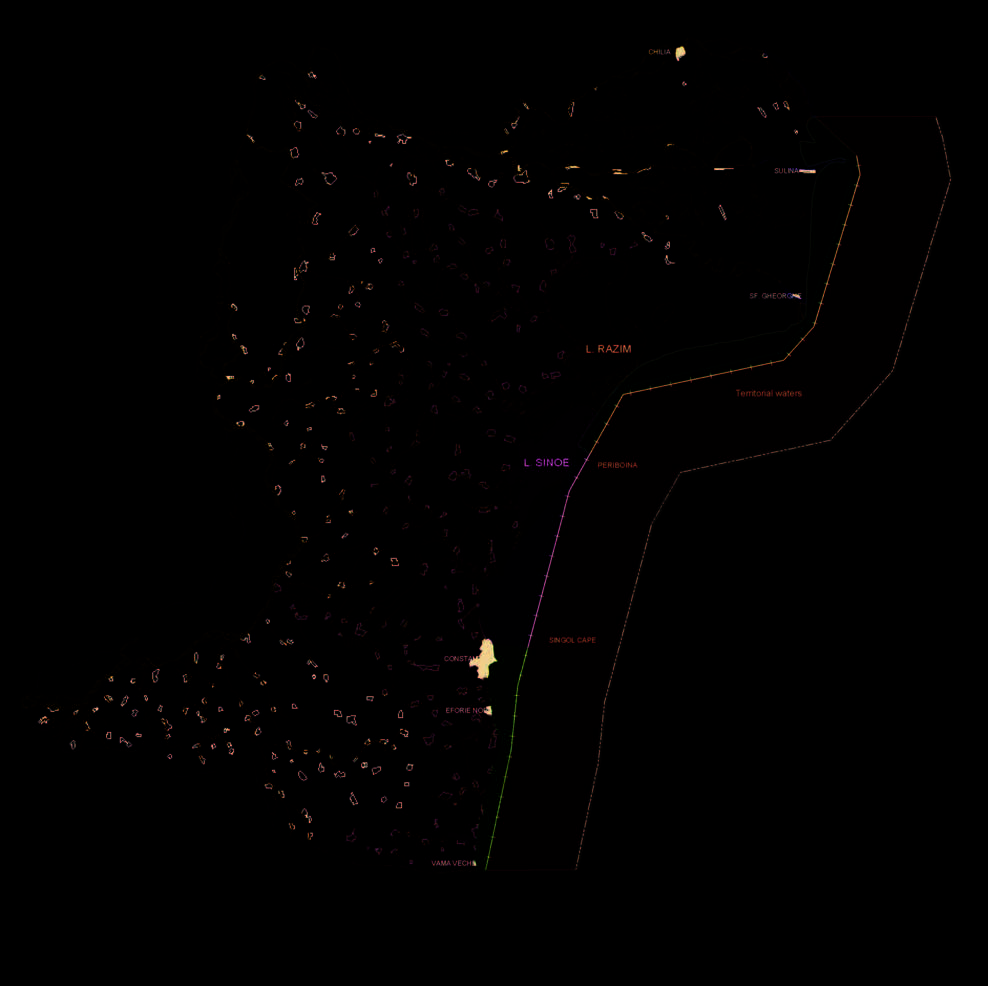

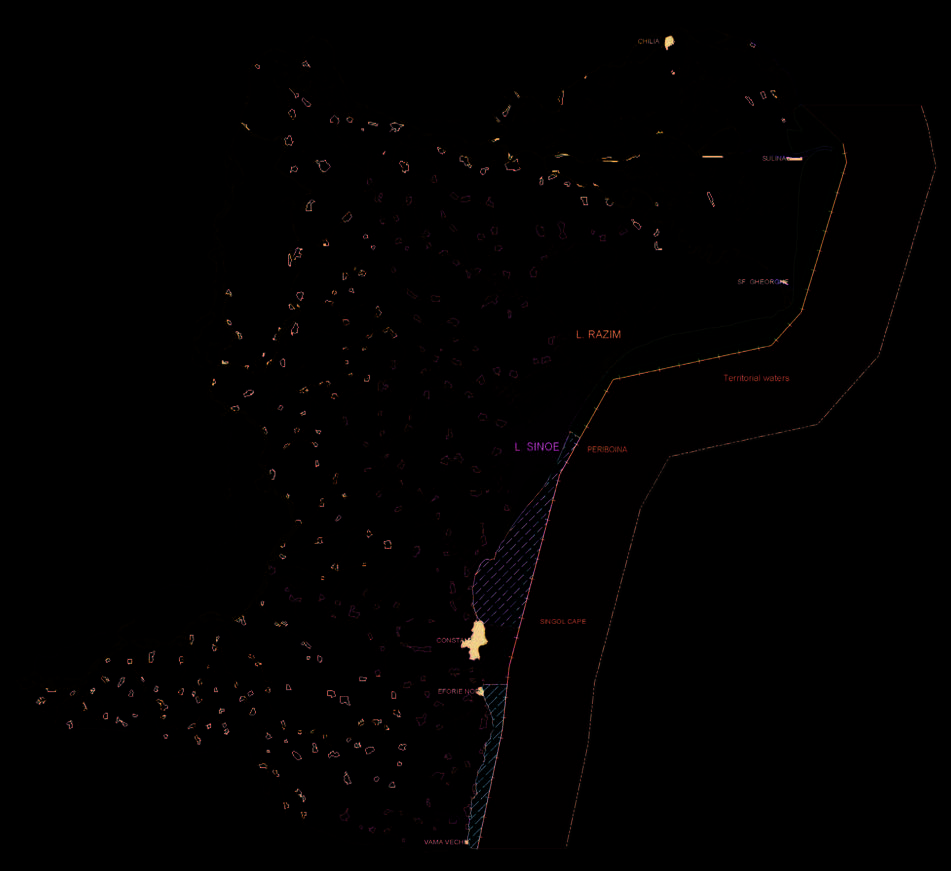

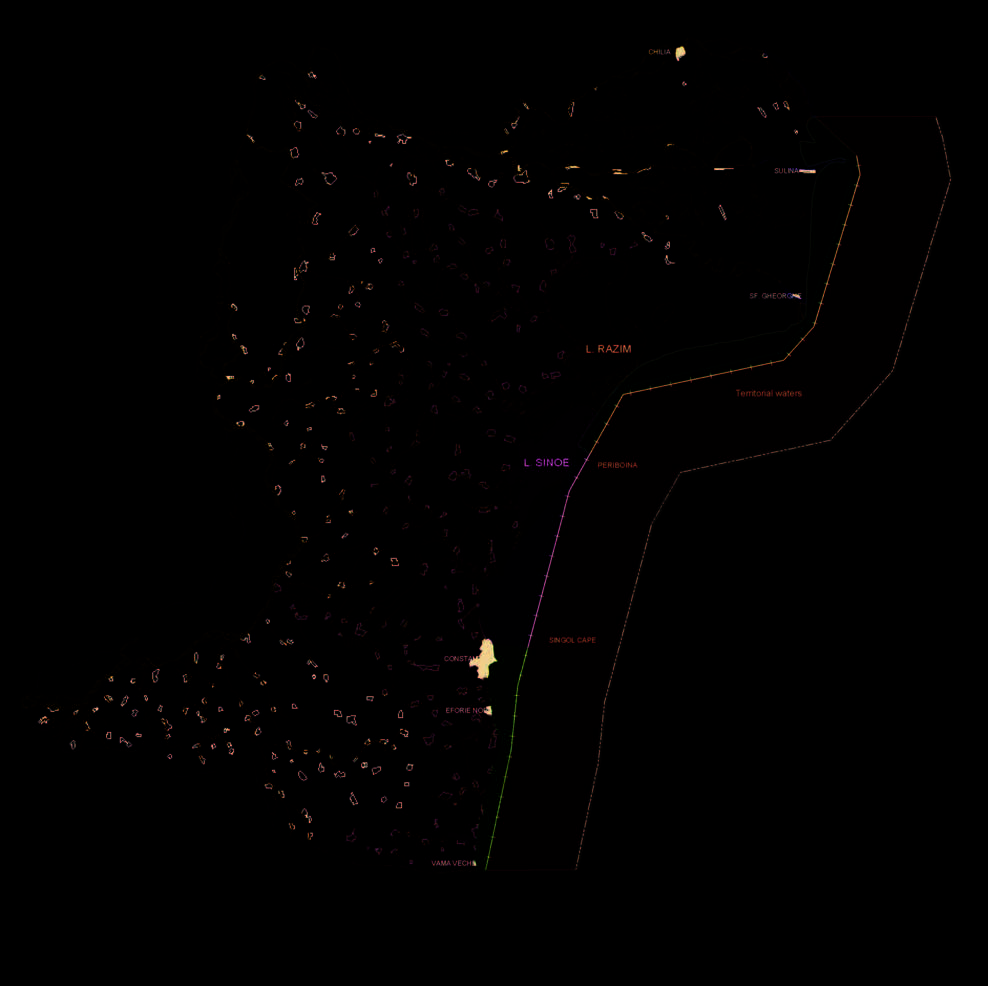

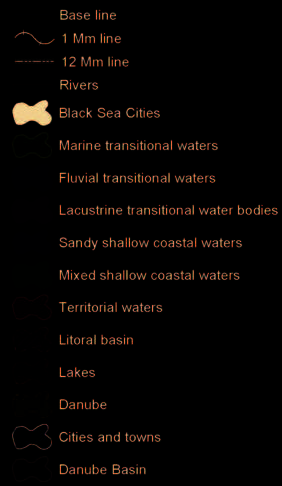

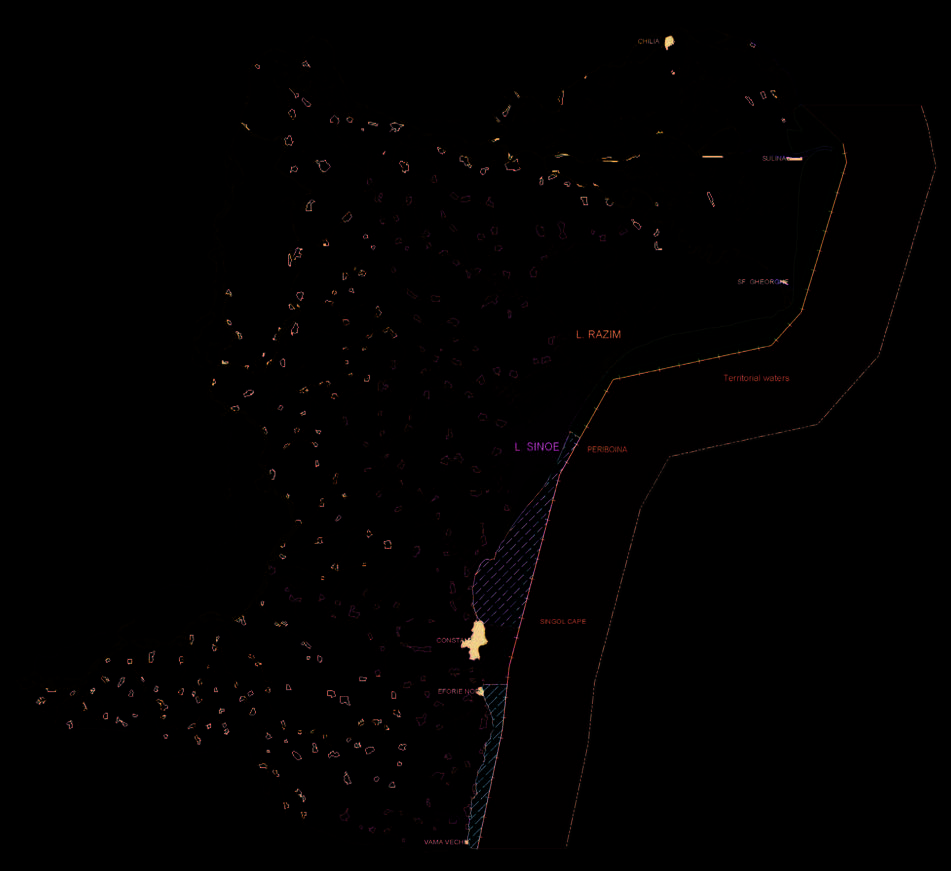

FIGURE 9

Location of transitional and coastal water types

46

FIGURE 10 Transitional and coastal water bodies in the Danube River Basin District

50

FIGURE 11 Inhabitant-specific N discharges from point sources (total load divided by total population in the state) in the Danube countries

for the period 1998 to 2000; results of the MONERIS application for this report

57

FIGURE 12 Inhabitant-specific P discharges from point sources (total load divided by total population in the state) in the Danube countries

for the period 1998 to 2000; results of the MONERIS application for this report

58

FIGURE 13 Portion of land use types in the total area of the Danube countries for the period 1998 to 2000 (data source FAO the exception is Germany -

DE* represents the land use for Baden- Württemberg and Bavaria according to the German Federal Statistical Office for the same period)

59

FIGURE 14 Portion of land use types at the parts of countries within the Danube basin and the average for the total Danube according to CORINE land

cover map and transferred USGS land cover map (source: SCHREIBER et al. 2003)

59

FIGURE 15 Consumption of nitrogen market fertilizers in the Danube countries, within the EU 15 countries, and EU maximum value in the period

1998 to 2000 (The bars represent the consumption of nitrogen market fertilizers per agricultural area of the Danube countries. The data

given for DE* represents the average N fertilizer consumption of the German "Länder" Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria. The database

is the national statistics published by the statistical offices of the countries or by FAO)

60

FIGURE 16 Consumption of nitrogen market fertilizers per inhabitant in the Danube countries, the EU 15 countries, and EU maximum value in the

period 1998 to 2000 (The bars represent the consumption of nitrogen market fertilizers per inhabitant living in the Danube countries.

The data given for DE* represents the average N fertilizer consumption of the German "Länder" Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria. The

database is the national statistics published by the statistical offices of the countries or by FAO)

61

FIGURE 17 Animal unit density per agricultural area in the Danube countries for the period 1998 to 2000. (The bars represent the animal units per

agricultural area in the Danube countries. The data given for DE* represents the animal unit density of the German "Länder" Baden-Württemberg

and Bavaria. The database is national statistics published by the statistical offices of the countries or by FAO, equivalents for Czech Republic

and Germany were used)

62

FIGURE 18 Animal units per inhabitant in the Danube countries for the period 1998 to 2000. (The bars represent the animal units per inhabitant in the

Danube countries. The data given for DE* represents the inhabitant-specific animal unit density of the German "Länder" Baden-Württemberg

and Bavaria. The database is national statistics published by the statistical offices of the countries or by FAO, equivalents for Czech Republic

and Germany were used)

62

FIGURE 19 Nitrogen surplus per agricultural area in the Danube countries for the period 1998 to 2000. Data sources: SCHREIBER et al. (2003), based on

data of FAO and national statistics for the German "Bundesländer"; data source for EU15 and EUmax: FAO (2004). The data of these sources

are not directly comparable, but give a general indication.

63

FIGURE 20 Phosphorus accumulation on agricultural area in the Danube countries for the period 1950 to 2000 (for data sources see Figure 19)

64

FIGURE 21 Agricultural area per inhabitant living in the Danube countries, the EU15 countries, the minimum in the EU15 countries, as well as the population

weighted average for the Danube basin for the period 1998 to 2000 (Data sources: see Figure 19)

65

FIGURE 22 Nitrogen surplus per inhabitant and year in the Danube countries for the period 1998 to 2000 (data sources: see Figure 19)

66

FIGURE 23 Pathways and processes used in MONERIS

67

FIGURE 24 Diffuse nutrient pollution by pathways for the total Danube river systems for the period 1998 to 2000; result of the MONERIS application

for this report

67

List of Figures 8

FIGURE 25 Total nutrient emissions by human sources and background values for the Danube river basin in the period 1998-2000

result of the MONERIS application for this report

68

FIGURE 26 Total N emissions by human sources for area of the countries within the Danube basin in the period 1998-2000

69

FIGURE 27 Total P emissions by human sources for area of the countries within the Danube basin in the period 1998-2000; result of the MONERIS application for

this report

69

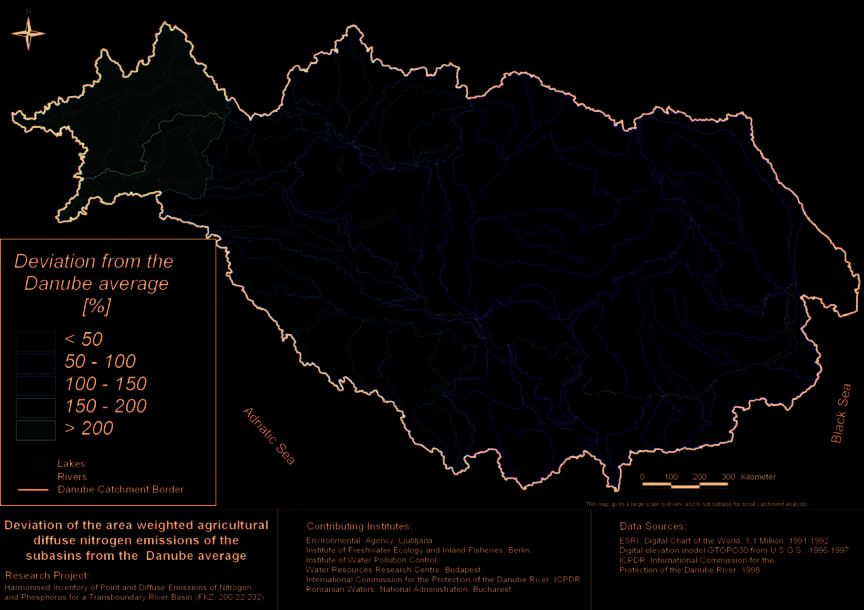

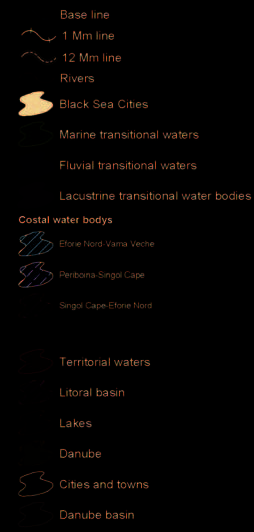

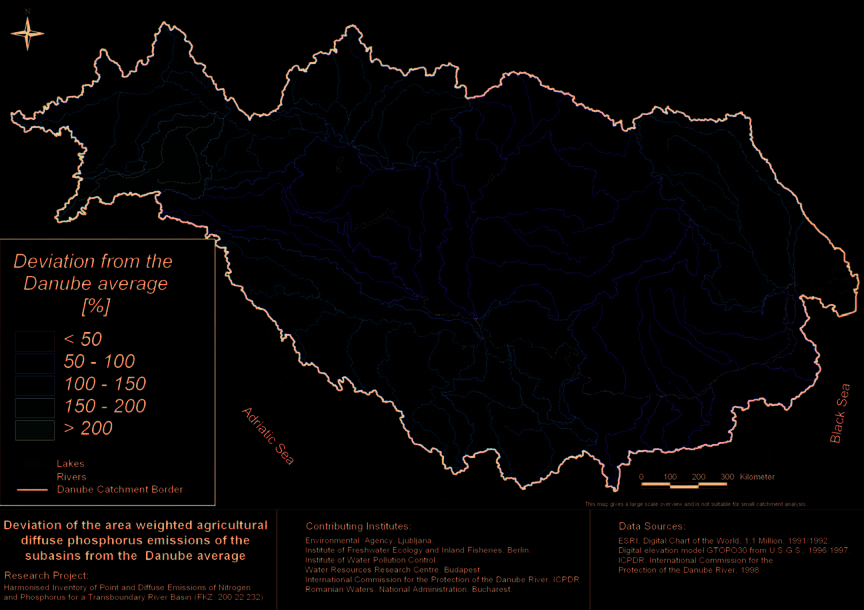

FIGURE 28 Deviations of the specific total diffuse nitrogen pollution from agricultural activities in the main sub-catchments of the Danube from the average for

the period 1998-2000

70

FIGURE 29 Deviations of the specific total diffuse phosphorus pollution from agricultural activities in the main sub-catchments of the Danube from the average

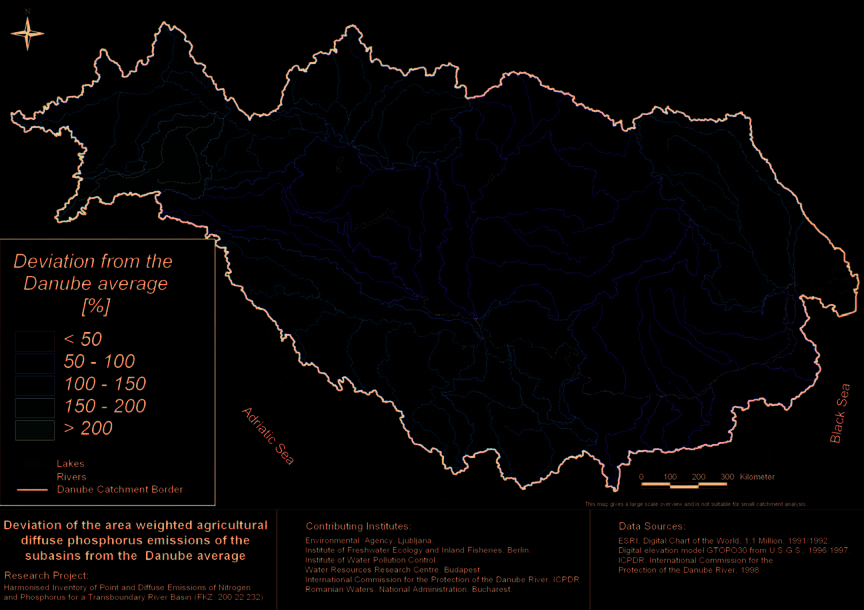

for the period 1998-2000

70

FIGURE 30 Temporal changes of the nitrogen emissions into the total Danube river system for the years 1955 to 2000 (see also Chapter 4.5.1.3)

71

FIGURE 31 Temporal changes of the phosphorus emissions into the total Danube river system for the years 1955 to 2000 (see also Chapter 4.5.1.3)

71

FIGURE 32 TNMN stations in the Danube river basin

85

FIGURE 33 Procedure for the estimation of the risk of failure to reach the environmental objectives of the WFD

86

FIGURE 34 Dissolved Oxygen - Spatial distribution of mean values of c10 for 1996 2000 data against the limit of Class II (TV - target value) the

Danube River Contrary to the other determinands, in the case of dissolved oxygen the "above target value" means a favorable situation

87

FIGURE 35 Dissolved Oxygen - Spatial distribution of mean values of c10 for 1996 2000 data against the limit of Class II (TV- target value) tributaries

Contrary to the other determinands, in the case of dissolved oxygen the "above target value" means a favorable situation

88

FIGURE 36 Biochemical Oxygen Demand - Spatial distribution of mean values of c90 for 1996 2000 data against the limit of Class II (TV - target value)

the Danube River. The values above the TV show unfavorable situations

89

FIGURE 37 Biochemical Oxygen Demand - Spatial distribution of mean values of c90 for 1996 2000 data against the limit of Class II (TV - target value)

tributaries. The values above the TV show unfavorable situations

89

FIGURE 38

Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD-Cr) Spatial distribution of mean values of c90 for 1996 2000 data against the limit of Class II (target value)

the Danube River. The values above the TV show unfavorable situations

90

FIGURE 39 Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD-Cr) Spatial distribution of mean values of c90 for 1996-2000 data against the limit of Class II (target value)

tributaries. The values above the TV show unfavorable situations.

90

FIGURE 40 Temporal trends of Cadmium in the Danube River

95

FIGURE 41 TNMN Water quality classes for cadmium and for mercury in 2001

96

FIGURE 42 Temporal trends of pp'-DDT in the Danube River

96

FIGURE 43 TNMN Water quality classes for Atrazine in 2001

97

FIGURE 44 Schematic representation of the nutrient balances in the surface water network

100

FIGURE 45 Overall assessment of present nutrient concentrations (on the basis of TNMN data from the year 2001)

101

FIGURE 46 Temporal and spatial trends of nitrate concentrations (data for the years 1996-2001; figures from TNMN Yearbook 2001; ICPDR 2001)

102

FIGURE 47 Temporal and spatial trends of the concentration of total phosphorus (data for the years 1996-2001; figures from

TNMN Yearbook 2001; ICPDR 2001)

103

FIGURE 48 Historical development of nutrient loads in the Danube River for dissolved inorganic nitrogen (top) and total phosphorous (bottom)

based on modelling results with MONERIS; the estimates refer to the Danube River before it enters the delta

104

FIGURE 49 Information related to the concentrations of chlorophyll-£\ in the Danube and its large tributaries, on the basis of TNMN field data

from 2001 (compare also Figure 50)

106

FIGURE 50 Concentrations of chlorophyll- \ [µg/l] in the Danube River on the basis of field data collected during the JDS (compare also Figure 49)

106

FIGURE 51 River load profiles of nitrogen (a) and phosphorus (b), subdivided over countries of origin derived from simulations with the

Danube Water Quality Model (DWQM) during the GEF-UNDP Danube Pollution Reduction Programme, 1999 UNDP/GEF (1999a)

108

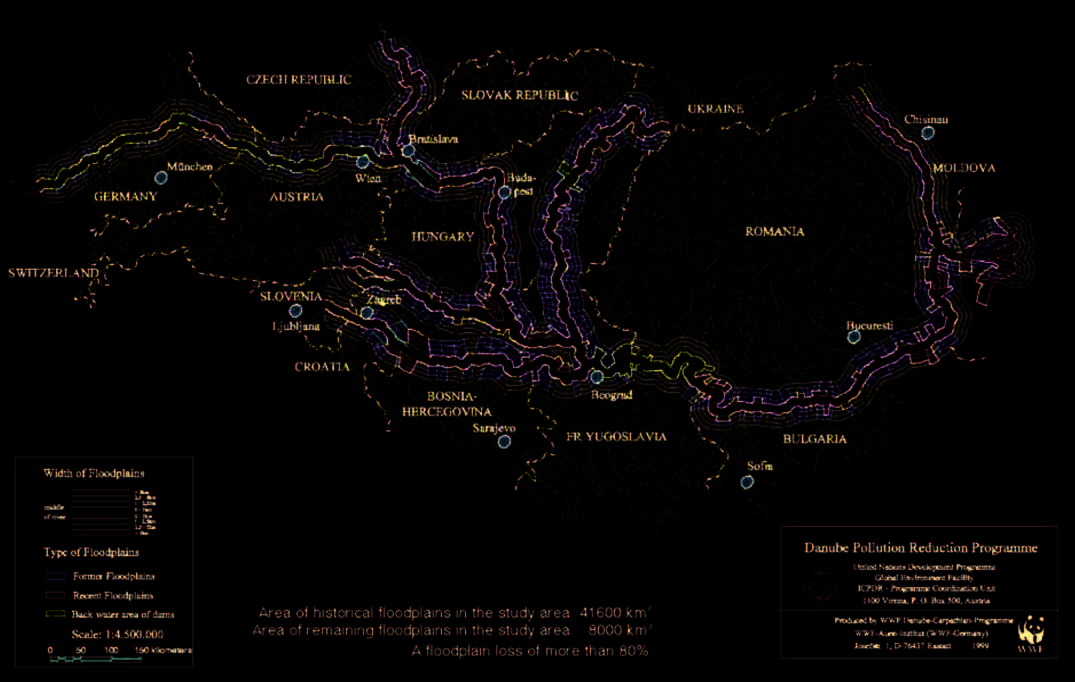

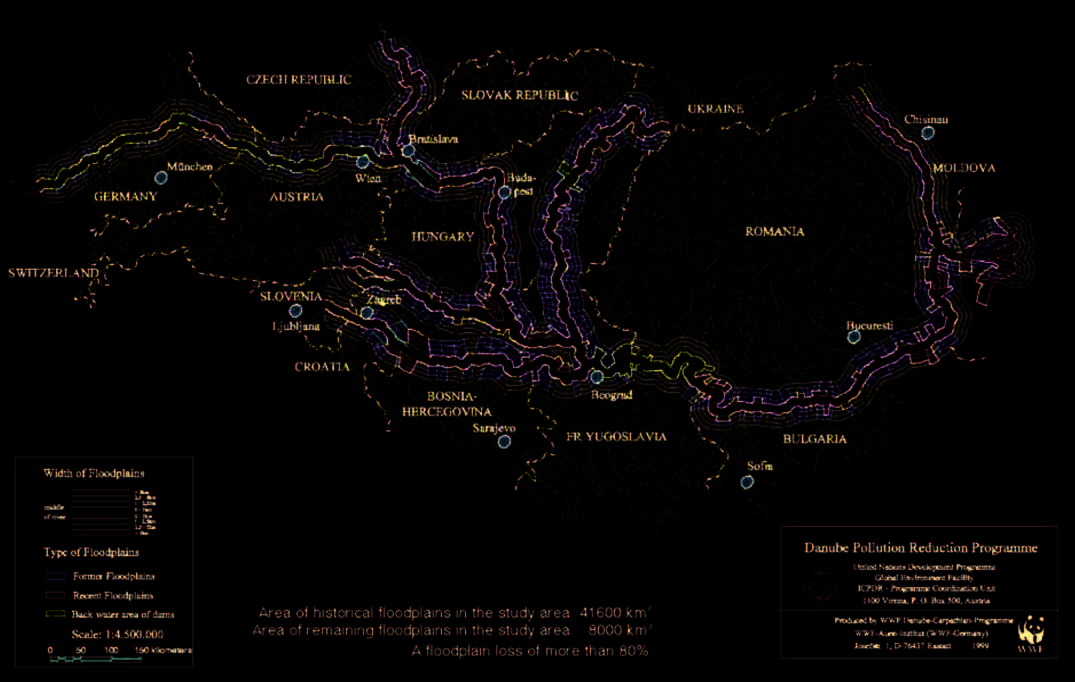

FIGURE 52 Symbolised view of floodplains in the Danube River Basin

FIGURE 53 Schematic representation of the distribution of water over the main Danube branches and the Delta complexes

111

FIGURE 54 The evolution of the inorganic nutrients concentrations (µM) in the Romanian coastal waters (Constanta monitoring site): phosphates (a),

silicates (b) and inorganic nitrogen (c) (Source: "State of the Environment of the Black Sea, Pressures and Trends, 1996 - 2000")

118

FIGURE 55 Development of the phytoplankton biomass in different parts of the Black Sea (derived by Horstmann and Davidov from field data

collected in the daNUbs research project)

120

FIGURE 56 Long term development of the N/P ratios in the Danube influenced waters off Constanta

121

List of Figures 9

FIGURE 57 Number of macro benthic species in front of the Danube delta (10 stations on 3 transects off Constanta, data from

C. Dumitrache, IRCM Constanta)

122

FIGURE 58 Development of seasonal areas of low oxygen concentration near the bottom on the northwestern shelf of the Black Sea

(after ZAITSEV & MAMAEV 1997)

122

FIGURE 59 Concentration of dissolved oxygen (expressed as % of saturation value) near the bottom on the Romanian shelf of the Western Black Sea

in September 1996, September 1999 and September 2003 (compiled in the daNUbs project from data collected by RMRI)

127

FIGURE 60 Main uses of the identified HMW sections on the Danube River

127

FIGURE 61 Main uses of the identified HMW sections on the tributaries of the DRBD

127

FIGURE 62

Physical alterations of the identified HMW sections on the Danube River

127

FIGURE 63

Physical alterations of the identified HMW sections on tributaries of the DRBD

127

FIGURE 64

Criteria used in expert judgement for the provisional identification of HMW sections on the Danube

128

FIGURE 65 Criteria used in expert judgement for the provisional identification of HMW sections on the tributaries of the DRBD

128

FIGURE 66 From the pressure and impact analysis to assessing the risk of failure to reach the environmental objectives

130

FIGURE 67 Risk classification of the Danube, disaggregated into risk categories. Each full band represents the assessment for one risk category

(hydromorphological alterations, hazardous substances, nutrient pollution, organic pollution). Colours indicate the risk classes.* SK territory.

133

10

List of Abbreviations

a.s.l.

above sea level

DRBD

Danube River Basin District

AEWS

Accident Emergency Warning System

DRBMP

Danube River Basin Management Plan

AOX

Adsorbable Organic Halogens

DRP

Danube Regional Project

AP

Action Programme

DRPC

Danube River Protection Convention

APC EG

Expert Group on Pollution, Prevention and Control

DTD

Danube-Tisza-Danube (Canal)

AQEM

The development and testing of an integrated assessment system

EC

European Commission

for the ecological quality of streams and rivers throughout Europe

ECO EG

Expert Group on Ecology

using benthic macroinvertebrates (EU-Project)

Econ ESG

Expert Sub-group on Economics

ARS

Accident risk spots

Eds

Editors

AT

Austria

EEA

European Environment Agency

AWB

Artificial Water Bodies

EEC

European Economic Community

BAT

Best available technology

EG

Expert Group

Bd

Band

EMIS EG

Expert Group on Emission

BG

Bulgaria

EPER

European Pollutant Emission Register

BOD

Biochemical Oxygen Demand

EQS

Environmental Quality Standards

BR

Biosphere Reserve

EU

European Union

BSC

Black Sea Commission

FAO

Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations

CCO-Mn

Chemical Oxygen Consumption

FAOSTAT

Database of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the

CEE

Central and Eastern Europe

United Nations

CIS

Common Implementation Strategy

FP EG

Expert Group on Flood Protection

CITES

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of

FP

Flood Protection

Wild Fauna and Flora

FPOM

Fine Particulate Organic Matter

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

GDP

Gross domestic product

COD-Cr

Chemical oxygen demand (dichromate method)

GEF

Global Environment Facility

COD-Mn

Chemical oxygen demand (manganesedichromate method)

GES

Good Ecological Status

CORINE

Coordination of information on the environment - CORINE

GIS ESG

Expert Sub-group on Cartography and GIS

land cover

GIS

Geographical Information System

CP

Contracting Party

GWP

Global Water Partnership

CPOM

Coarse Particulate Organic Matter

HMWB

Heavily Modified Water Body

CS

Serbia and Montenegro

HPP

Hydro-Power Plant

CZ

Czech Republic

HPS

Hydroelectric Power Station

daNUbs

Nutrient Management in the Danube Basin and its Impact

HR

Croatia

on the Black Sea

Hrsg

Herausgeber (Editor)

DBSC

Danube-Black Sea Canal

HU

Hungary

DDNI

Danube Delta National Institute for Research and Development

IAD

International Association for Danube Research

DDT

Chlorinated Organic Insecticides-1,1,1-Trichloro-2,2-bis-

IAWD

International Association of Water Supply Companies in the

(4'-chlorophenyl) ethane

Danube River Catchment Area

DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

IBA

Important Bird Area

DE

Germany

ICPDR

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

DEF

Danube Environmental Forum

IHD

International Hydrological Decade

DIN

Dissolved Inorganic Nitrogen

IHP

International Hydrological Programme of the UNESCO

DO

Dissolved oxygen

IRCM

Institutul Roman de Cercetari Marine, Constanta

DOC

Dissolved Organic Carbon

IUCN

International Union for the Conservation of Nature

DPRP

Danube Pollution Reduction Programme

JAP

Joint Action Programme

DRB

Danube River Basin

JDS

Joint Danube Survey

List of Abbreviations 11

km

kilometre

RefCond

Reference Conditions

MHQ

mean high flow

rkm

river kilometre

MLIM EG

Expert Group on Monitoring, Laboratory and Information

RMRI

Romanian Marine Research Institute

Management

RO

Romania

MLIM

Monitoring, Laboratory & Information Management

RR

Roof Report

MNQ

mean low flow

Si

Silica

MONERIS

Modelling Nutrient Emissions into RIver Systems

SI

Slovenia

MoU

Memorandum of Understanding

SK

Slovak Republic

MQ

mean flow

SWG

Standing Working Group

N

Nitrogen

t

ton

na

not available

TEN

Trans-European Transport Networks

NGO

Non-governmental Organisation

TNMN

Transnational Monitoring Network

OECD

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

TOC

Total Organic Carbon

OJ

Official Journal

TP

Total Phosphorus

OM

Ordinary Meeting

TS

Technical Support

P

Phosphorus

TV

Target value

PAHs

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

UBA

Umweltbundesamt (Federal Environment Agency)

PAMNC

Poarta Alba Midia Navodari Canal

UN/ECE

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

PIAC

Principal International Alert Centre

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

POPs

Persistent Organic Pollutants

UNESCO

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation

PPP

Purchase power parity

USGS

United States Geological Survey

PRTR

Pollutant Release and Transfer Register

VOCs

volatile organic compounds

PS

Permanent Secretariat

Vol

Volume

RBI

River Basin Initiative

WFD

Water Framework Directive

RBM EG

Expert Group on River Basin Management

WRI

Water risk index

RBM

River Basin Management

WWF

World Wide Fund for Nature

REC

Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe

WWTP

Waste Water Treatment Plant

Mario Romulic, Croatia

12

1. Introduction

1.1. Aim of the report

This report responds to reporting obligations of the Water Framework

This report therefore has different addressees:

Directive 2000/60/EC (WFD) under Article 5, Annex II and Annex III

the countries in the Danube river basin, this report being the common basis

regarding the first characterisation and analysis of the Danube River

for river basin management on the basin-wide scale,

Basin District. In addition, information is given on progress related to

the European Commission, to inform on the progress of WFD implementation,

Article 6 and Annex IV for setting up an inventory of protected areas

and

in the river basin district, as well as on progress related to Article 14

all interested parties as well as the general public, to inform about the

regarding public information and consultation.

results of the first analysis of the Danube River Basin District and to prepare

for the consultation process.

This report is the second report to the European Commission on the

progress of implementation of the WFD. The first report dealt with

the reporting obligations under Article 3.8 and Annex I related to the

1.2. Structure and contents of the report

delineation of the Danube River Basin District, the identification of

The Danube River Basin is the second largest river basin of Europe

the competent authorities for WFD implementation and on the

covering territories of 18 states including EU-Member States,

international coordination arrangements for international river basin

Accession Countries and other states. In addition to the Danube River

districts. The WFD Roof report 2003 (see explanations in Chapter 1.2)

Basin the Danube River Basin District (DRBD) includes some of the

was completed on 26 April 2004 and sent to the Commission on

Black Sea coastal catchments (see Chapter 2.1). Due to the large

22 June 2004.

number of states and the coordination requirements in the DRBD (see

Chapter 2.3) the report on the DRBD has been divided into two parts.

Annex II and III of the Directive stipulate the analysis of environmen-

Part A (roof report) gives the basin-wide overview; Part B (national

tal and economic characteristics including the assessment of

reports) gives all relevant further information on the national level as

significant anthropogenic pressures and impacts in surface waters

well as information coordinated on the bilateral level (see Figure 1).

and groundwater. This analysis forms the basis for the assessment

of the status of surface waters and groundwater in Europe and

The International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

illustrates, which water bodies are "at risk" of failing the environmen-

(ICPDR) is the implementing body under the "Convention on

tal objectives. The future developments of monitoring networks and

Cooperation for the Protection and Sustainable Use of the Danube

of the programme of measures will be based on the results of this

River" (Danube River Protection Convention, DRPC) and serves as

analysis.

the platform for coordination to develop the Danube River Basin

Management Plan (DRBMP). The ICPDR has a coordinating and

Article 14 of the Directive specifies that Member States shall

supporting function, but does not report on its own.

encourage the active involvement of all interested parties in the

implementation of the Directive and in the development of river

Each EU Member State will send the Roof report (Part A) together

basin management plans.

with its own national report (Part B) to the European Commission. In

addition, the ICPDR will informally send to the European

Commission a copy of the Roof report and a copy of the national

reports (Part B) of those countries, which are (currently) not obligated

to report to the European Commission (Bosnia i Herzegovina,

Bulgaria, Croatia, Moldova, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, and

Ukraine). This approach was also undertaken for the delivery of

information required according to Art. 3 (8) and Annex I WFD.

Introduction 13

Structure of the report for the

Part A Roof report

Danube River Basin District1

FIGURE 1

The Roof report gives the basin-wide overview on issues requiring

Part A: Roof report coordinated by the ICPDR

reporting under WFD. It provides information on the main surface

Part B: National reports

waters, which are shown in the Danube River Basin District overview

GERMANY

EU-Member State

map (Map 1) and the important transboundary groundwaters shown in

Map 15.

AUSTRIA*

EU-Member State

CZECH REPUBLIC

EU-Member State

The Roof report includes, in particular, an overview of the main

SLOVAK REPUBLIC**

EU-Member State

pressures in the DRBD and the related impacts exerted on the

HUNGARY

EU-Member State

environment. The overview includes effects on the coastal waters of

SLOVENIA

EU-Member State

the Black Sea as far as they are part of the DRBD, since their status

CROATIA

Accession Country

could be a reason for designating the whole DRBD as a sensitive area.

BOSNIA I HERZEGOVINA

Other

SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO***

Other

The analysis is based on available data resulting from past and

ongoing programmes and projects and a hierarchy of information

BULGARIA

Accession Country

used has been defined (see Chapter 1.3). The contents of the Roof

ROMANIA

Accession Country

report results from the work of the ICPDR expert groups and has

MOLDOVA

Other

been approved by the ICPDR at its Ordinary Meetings. The issues

UKRAINE

Other

referred to in the basin-wide overview will be the basis for the

including bilateral coordination:

*

with Switzerland and Italy,

preparation of the Danube River Basin Management Plan by the

**

with Poland

end of 2009.

*** with Albania and Macedonia

The Roof report intends to give an overview of the situation in the

Danube river basin district as a whole and to set the frame for the

understanding of the detailed national reports. The Roof report is

therefore comparatively brief. Detailed information is given in the

national reports.

Part B National reports

The National reports give all relevant further information on the

national level as well as information coordinated on the bilateral

level. Transboundary issues not covered by the ICPDR are solved at

the appropriate level of cooperation e.g. in the frame of bilateral/

multilateral river commissions. The national information is given in

addition to the information in Part A.

1 This figure reflects the situation at the time of reporting (March 2005).

Introduction 14

Interplay between Part A (Roof report) and Part B (National reports)

Regarding Annex III Economic analysis

The Roof report addresses those issues of Annex II, III and IV WFD

The Roof report addresses three issues:

relevant on the basin-wide scale, i.e. information concerning the

assessment of the economic importance of water uses,

1. Analysis of surface waters (Annex II, 1.)

projection of trends of key economic indicators and drivers up to 2015, and

2. Analysis of groundwaters (Annex II, 2.)

assessment of current levels of cost recovery of water services.

3. Economic analysis (Annex III)

The assessment of current levels of cost recovery of water services

4. Inventory of protected areas (Annex IV)

and the cost-effectiveness of measures is not analysed on the basin-

wide level as these issues are primarily of national importance. This

In addition, an overview will be given on steps undertaken on

report gives some general considerations on the issue, but the actual

the basin-wide level for public information and consultation.

analysis will be contained in the National reports (Part B).

Table 1 shows which information which will be given in which

part of the report.

Regarding Annex IV Inventory of protected areas

The protected areas for drinking water abstraction, for economically

Regarding Annex II 1. Analysis of surface waters

significant aquatic species, for recreational waters and the nutrient-

The Roof report gives an overview for the following surface waters:

sensitive areas (including vulnerable zones) are generally not of trans-

the Danube and its tributaries with a catchment size of > 4 000 km2,

boundary importance. These inventories have been set up nationally

all lakes and lagoons with an area of > 100 km2,

and are dealt with in the national reports.

the main canals,

transitional and coastal waters.

Wetlands play an important role in the Danube River Basin and many

A summary of the relevant information on surface waters will be

of them are transboundary and under international protection.

given in Part A. Detailed information will be in Parts B.

Therefore, an inventory of protected areas for species and habitats has

been set up where the maintenance or improvement of the status of

Regarding Annex II 2. Analysis of groundwaters

water is important for their protection. The protected areas selected

Groundwaters are generally of local or regional importance and are

for the basin-wide overview have been defined as follows

described in detail in the national reports. The Roof report gives an

an international protection status (RAMSAR and World Heritage Convention,

overview for important transboundary groundwater bodies according

UNESCO/ MAB and/or IUCN category II or Natura 2000 site), and

to the following criteria:

a size of > 1,000 ha.

all transboundary groundwater bodies > 4000 km2,

transboundary groundwater bodies < 4000 km2, if they are very important;

The National reports address all issues listed in Annex II and III WFD.

the identification as important has to be bilaterally agreed. The agreement

must include the criteria for the importance, e.g. socio-economic importance,

groundwater use, impacts, pressures, interaction with aquatic eco-systems.

Introduction 15

Issues covered in Part A (Roof report) and Part B (National reports)

TABLE 1

Part A Roof report

Part B National reports

Article 5 and

ANNEX II 1. ANALYSIS OF SURFACE WATERS

1.1 Surface water categories

X

X

1.2 Ecoregions and surface water types

X

X

1.3 Establishment of type-specific reference conditions

X

X

1.4 Identification of pressures

X

X

1.5 Assessment of impacts

X

X

ANNEX II 2. ANALYSIS OF GROUNDWATERS

2.1 Initial characterisation

X

X

2.1 Further characterisation

X

2.3 Review of the impact of human activity

X

X

2.4 Review of the impact of changes in groundwater levels

X

2.5 Review of the impacts of pollution on groundwater quality

X

X

ANNEX III ECONOMIC ANALYSIS

(a) Analysis of water uses incl. levels of cost-recovery for water services

X

X

(b) Judgements of most cost-effective combination of measures in respect of water uses

X

Article 6 and

ANNEX IV INVENTORY OF PROTECTED AREAS

1. (i) for abstraction of water intended for human consumption

X

1. (ii) for protection of economically significant aquatic species

X

1. (iii) as recreational waters, incl. areas designated as bathing waters

X

1. (iv) nutrient-sensitive areas, incl. areas designated as vulnerable zones

X

1. (v) for protection of habitats or species where the maintenance or improvement of

the status of water is important for their protection

X

X

Article 14

PUBLIC INFORMATION AND CONSULTATION

X

X

Introduction 16

1.3. Status of the report and disclaimer

In some cases, national data, which were available only for one or few

This report is the first comprehensive characterisation and analysis

countries, have not been used if there were alternative published data

for the entire Danube River Basin, in which all 13 Danubian countries

from other sources for the entire Danube basin, e.g. generated through

cooperating under the DRPC have participated. The nature, the

modelling tools. On one hand, the advantage of such an approach is

extent and the quality of the available data and information varies

that largely comparable data, e.g. generated through modelling,

considerably in relation to the issues and the countries concerned. All

for the DRBD can be presented. However, this approach leads to a

countries of the Danube basin have committed themselves to develop

number of consequences, which have to be born in mind when

jointly a Danube River Basin Management Plan by the end of 2009,

interpreting the findings of this report:

and, as a first step, provide the required information for this report.

1. Official national data have not been used and may, in some cases, differ

Some of the experiences while compiling the report are listed below

from the Danubewide data set. If the modelled data had been replaced by the

and should be born in mind when reading and interpreting the report.

national data only for some countries, the level of comparability would have

decreased. Hence, more emphasis was given on the relative quantitative

The key objective was to compile comparable data and information

levels rather than the correct absolute values.

throughout the basin and to generate the level of detail or aggregation

2. In particular, results used in this report stemming from models (e.g.

required for the assessment of transboundary and basinwide issues.

MONERIS) are focussed on a Danube-wide scale and in a generic way, these

Thus, for surface water, data collection focused mainly on the Danube

results have not been used to derive conclusions for particular countries or

River and, in most cases, on the main rivers and lakes as identified in

regions. The assumptions of the model and the input data are not fully repro-

the DRBD overview map. For groundwater, the focus was on the

duced in this report but are published in secondary literature. Some countries

important transboundary groundwater bodies. A more detailed level

may not agree with the estimations of such models, in particular when a

of the analysis will be presented in the national reports. Hence, this

more detailed analysis has been carried out on the national level. However, it

report should only be read and interpreted in conjunction with the

was appropriate to draw conclusions from the modelling results for a

national reports. Where inconsistencies may have occurred, the na-

comparison on the basin-wide scale.

tional report may provide the latest up to date information since they

3. Natural conditions may vary, and thereby significantly influence the results of

have been finalised several months after this report. In other words,

the modelling, e.g. data used in MONERIS for the upper part of the Danube

some of the data presented in this report were presented as a first

basin was based on a wet period, which included a major flood event. This

approximation or at a different level of aggregation but the finally

has led to the overestimation of nutrient loads for this area.

agreed result on the national level was only becoming available after

the final date of data delivery for this report as mentioned below.

In summary, the results of modelling and other publicly available data

and information have only been used if they provided added value to

The report is mainly based on available data. Wherever possible, the

the report and only generic conclusions have been drawn on the basis

following hierarchy of information has been used:

of those data. In most cases, it was an indication that official and

1. data that has previously been collected in the context of the ICPDR, e.g.

comparable data for the Danube basin do not yet exist.

results of the TransNational Monitoring Network

(1996-2000), the ICPDR Emission Inventory (status 2002) or the results

For some issues it was possible to get expert input through support of

of the Joint Danube Survey2 conducted in 2001;

the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project3. The contribution of the

2. data and information officially delivered by the competent authorities of the

Danube Regional Project consisted of

DRB countries (collected by the ICPDR in templates or questionnaires) during

conducted studies for the characterisation of surface waters and

the preparation of the report (data mostly from 2004) based on agreed

groundwater (development of a typology of the Danube River, study on hydro-

criteria;

morphological alterations in the DRB); Agricultural policy study as a

3. other published data and information.

contribution to the pressure and impact analysis; Contributions to the

economic analysis; and the development of a Public Participation Strategy;

The reference of the data sources has been included, in particular

specialised workshops for capacity building and for coordination/harmonisa-

for material used from the third category. Whenever a reference is

tion of WFD implementation amongst DRB countries;

missing, it can be assumed that the data fall under the second

data collection via templates and questionnaires, drafting of specific

category. The maps generated for this report are either produced by

chapters of this report, and preparation of DRBD maps for WFD topics

the ICPDR on the basis of data sources categories 1 or 2, or maps

through consultants input.

from other sources have been used and clear reference is provided.

2 ICPDR (2002).

3 United Nations Development Programme / Global Environment Facility Project: "Strengthening the Implementation Capacities for Nutrient Reduction

and Transboundary Cooperation in the Danube River Basin".

Introduction 17

As regards reporting obligations under the Water Framework

Moldova is attempting to meet the requirements of the WFD and has

Directive for EU Member States, this report together with the national

progressed jointly with Romania, with whom Moldova shares a

report will comprise the package of information sent to the European

border, in undertaking the necessary work to prepare the necessary

Commission in order to enable an assessment of the compliance and

information collection and assessment for reporting under WFD.

conformity with the Directive. Given the situation of data availability

Ukraine is at the beginning of preparing the necessary internal

described below, this report on its own may not be sufficient to

structures and management arrangements for WFD implementation

completely fulfil the requirements of the Directive, in particular when

and has discussed with the ICPDR and the UNDP Danube Regional

pragmatic approaches or generalisations had to be applied on the

Project potential assistance in capacity building related to this issue.

basin-wide level in order to come up with a first screening analysis

No timetable for completing tasks or meeting requirements has yet

within the very short available time frame.

been developed.

Moreover, the harmonisation of approaches and methodologies

All of the countries have, however, progressed with the work

throughout the basin is only at the beginning. In some areas, harmoni-

necessary and have attempted to organize their internal structures to

sation and comparability of data is already advanced (e.g. the TNMN)

meet the requirements of the Water Framework Directive.

or harmonised work was carried out for the purpose of this report

(e.g. the typology for the Danube river). In other areas, it was

This report is based on data delivered by the Danube countries by

necessary to rely completely on national approaches and thereby

8 November 2004. Data that has been compiled after this date will

presenting data based on a diversity of approaches. Whenever

only be contained in the national reports. Where data was not

harmonised criteria are being used in the report, the thresholds should

delivered by the countries other data sources were used where they

be interpreted as significant in the transboundary and basin-wide con-

were available. Other sources than the competent authorities of the

text of the Danube river basin. Given the immense size of the DRBD,

Danube River Basin have been clearly identified in the report.

it seems evident that criteria determining significance in the sense of

the Water Framework Directive are likely to be much more stringent.

As regards countries with a share of less than 2000 km2 in the DRBD,

Thereby the report only identifies the "major" problems, more stringent

Austria, Slovakia, and Serbia and Montenegro have endeavoured to

criteria in line with the Directive and protecting much smaller water

establish appropriate coordination with these neighbours. Italy and

bodies (e.g. lakes smaller than 100 km2 or groundwater bodies

Switzerland have submitted geographical data for this report. Poland

smaller than 4000 km2) must be used in the national reports. The data

delivered data to the Slovak Republic, through the Transboundary

concerning transboundary watercourses was bilaterally harmonised.

Commission established in the frame of bilateral agreement between

the Slovak Republic and Poland. Albania and Macedonia communicated

In view of the above, the delivery of data from EU Member States4

the competent authorities for water management issues.

and Candidate Countries5 in the Danube River Basin District6 was

satisfactory, even though there is still considerable divergence in the

In conclusion, this first assessment reflects the current level of prepa-

level of detail and availability of data from upstream to downstream.

ration for a harmonised, integrated river basin management. The

As regards the other Danubian countries, the situation during the

extent, the quality and the degree of harmonisation of the data will

preparation of the report was as follows:

improve with future reviews and updates of the characterisation and

Serbia and Montenegro after becoming a full Contracting Party to the

analysis making later assessments more comprehensive and robust.

Danube River Protection Convention in August 2003 has developed

Notwithstanding, this first analysis is an outstanding milestone and

a detailed timetable to complete the necessary work for the 2004

provides a sound basis for the next stages of the implementation of

report by the end of 2004.

the Water Framework Directive, in particular the development of the

Bosnia i Herzegovina is in the process of internal reorganization of the

monitoring programmes and the river basin management planning

water management sector to meet requirements of the Water Frame-

process. To this end, the identified gaps and deficiencies will guide

work Directive and has begun work to prepare the needed information.

the followup activities after finalisation of this report, in line with the

Croatia has also reoriented its water management in line with the

principles identified by the EU Common Implementation Strategy for

WFD, has undertaken most tasks needed and provided the majority

the Water Framework Directive.

of the information required for this report.

4 Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia.

5 Bulgaria, Romania (note: Croatia has become a new EU Candidate Country in June 2004 when the most part of the preparatory work was finalised).

6 Only referring to those 13 Danubian countries, which have a share of the Danube River Basin District larger than 2000 km2.

18

2. The Danube River Basin District and its

international coordination arrangements

Most of the information given in this chapter is taken from the Danube Roof Report 2003 (Art. 3.8 and Annex I), but is provided here to help readers use this

report as an alone-standing document.

2.1. Delineation of the Danube River Basin District

The International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

The Danube River Basin is the second largest river basin of Europe7

(ICPDR) is the implementing body under the "Convention on

covering 801,463 km2 and territories of 18 states including EU-Mem-

Cooperation for the Protection and Sustainable Use of the Danube

ber States, Accession Countries and other states that have not applied

River" (Danube River Protection Convention, DRPC) and serves as

for EU Membership. According to Article 3.3 of the WFD "Member

the platform for coordination to develop and establish the Danube

States shall ensure that a river basin covering the territory of more

River Basin Management Plan (DRBMP).

than one Member State is assigned to an international river basin

district". Where a river basin district extends beyond the territory of

The Danube River Basin District has been defined in the frame of the

the Community, the WFD requests the Member State or Member

work of the ICPDR. It covers 1) the Danube River Basin, 2) the Black

States concerned to "endeavour to establish appropriate coordination

Sea coastal catchments on Romanian territory, and 3) the Black Sea

with the relevant non-Member States, with the aim of achieving the

coastal waters along the Romanian and partly the Ukrainian coast.

objectives of this Directive throughout the river basin district."

(Art. 3.5 WFD). The main objective of WFD implementation is the

development of a Danube River Basin Management Plan.

Area of the Danube River Basin District

TABLE 2

Territory

Official area [km2]

Digitally determined area [km2]*

Danube River Basin (DRB)

18 countries (see Table 3)

801,463

Black Sea coastal river basins

Romania

5,198

5,122

Black Sea coastal waters

Romania and Ukraine

1,242

Danube River Basin District (DRBD)

807,827

* For the purpose of comparison the areas were calculated using GIS on the basis of the DRBD overview map. The value for

the Black Sea coastal river basins differs slightly from the official data, since other methods of calculation have been used.

7 The area of the DRB was determined digitally with GIS. If other sources are consulted this value may vary slightly,

because other methods of calculation have been used.

The Danube River Basin District and its international coordination arrangements 19

Map 1 shows the geographical coverage of the Danube River Basin

The coastal waters of the DRBD extend along the full length of the

District as well as the competent authorities. The outer boundary

Romanian coastline and along part of the Ukrainian coast up to the

of the Danube River Basin District was defined taking into considera-

hydrological boundaries of the Danube River Basin. The Romanian

tion the hydrological boundaries of the surface waters and ground-

coastal waters were included in the DRBD, because the water quality

water. In a few small places the district boundaries of groundwater

and the morphology of the seashore are substantially influenced by

and surface waters are not aligned (Germany, Slovenia, Serbia and

the Danube River. The Romanian coastal waters are delineated at

Montenegro, Bosnia i Herzegovina, and Bulgaria). Details can be

1 nautical mile from the baseline, which is defined along 9 points

found in the respective national reports.

within the territorial sea of Romania as laid down in the Romanian

Law No. 17/1990, modified by Romanian Law No. 36/2002. A

In addition to the Danube River Basin, the small coastal basins of the

detailed description of the coastal waters is contained in the

Black Sea tributaries lying on Romanian territory between the eastern

Romanian national report (Part B). The Ukrainian coastal waters are

boundary of the DRB and the coastal waters of the Black Sea have

not defined by Ukrainian law. For WFD implementation the coastal

been included in the Danube River Basin District. Here also lies the

waters are defined in line with Art. 2.7 WFD at 1 nautical mile from

Danube-Black Sea Canal (Canal Dunarea-Marea Neagra), which

the baseline.

diverts part of the water of the Danube River directly to the Black

Sea. These coastal catchments were included in the DRBD, because

The coastal waters of Bulgaria are not included in the DRBD, since

they influence the coastal waters along the Romanian coastline.

their characteristics are substantially influenced by rivers on

Bulgarian territory flowing into the Black Sea and by processes in the

Black Sea itself. Bulgarian coastal waters are assigned to the

Bulgarian Black Sea River Basin.

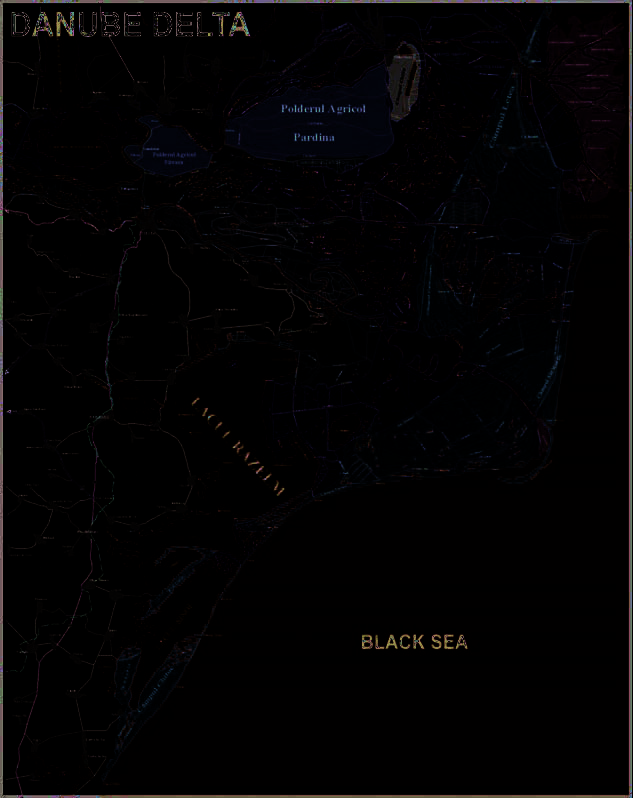

Danube River Basin District - Overview

MAP 1

The Danube River Basin District and its international coordination arrangements 20

2.2. States in the Danube River Basin District

States in the Danube River Basin District

TABLE 3

18 states have territories in the Danube River Basin District. Besides

State

ISO-Code

Status in the European Union*

Austria, Germany, and Italy, five additional Danube countries have

Albania

AL

-

become EU Member States on May 1, 2004. At the time of reporting,

Austria

AT

Member State

three other Danube countries are in the process of accession and are

Bosnia i Herzegovina

BA

-

preparing to fulfil the complete body of EU legislation in order to

Bulgaria

BG

Accession Country

become EU Members. Seven states have not initiated a formal

Croatia

HR

Accession Country

process to join the EU (see Table 3).

Czech Republic

CZ

Member State

Germany

DE

Member State

For the EU Accession countries the WFD is part of the `acquis

Hungary

HU

Member State

communautaire'. By the time the deadline for the completion of the

Italy

IT

Member State

River Basin Management Plan is reached in December 2009

Macedonia

MK

-

probably two more Danube countries, Bulgaria and Romania, will

Moldova

MD

-

have become EU Members. Croatia has officially become an

Poland

PL

Member State

Accession Country in April 2004 and will begin its accession

Romania

RO

Accession Country

negotiations in 2005. Although these countries have no reporting

Serbia and Montenegro

CS

-

obligations until they become EU-Member States, they are

Slovak Republic

SK

Member State

cooperating in the frame of the ICPDR to implement the necessary

Slovenia

SI

Member State

steps just as the other Non-EU States.

Switzerland

CH

-

Ukraine

UA

-

* The table reflects the situation at the time of reporting (March 2005).

The Danube River Basin District and its international coordination arrangements 21

Table 4 shows the coverage of the states in the DRB and the estimated

The Danube River Basin has a rich history with a strong cultural

population in the basin. The territory of Hungary is 100 % within

heritage. This is also reflected in the large number of ethnic groups

the basin. Romania, the Slovak Republic and Austria lie almost

in the basin and the large number of languages still spoken (at least

completely within the DRB (96 97 % of state). Countries sharing

17 official languages in the DRB). The official languages of the

< 2000 km2 are (in descending order by size) Switzerland, Italy,

ICPDR are English and German; English is the language used.

Poland, Albania and Macedonia. Romania contributes by far the

largest population in the DRB (more than 26 %), followed by

Hungary, Germany, and Serbia and Montenegro with nearly equal

percentages of the total population in the DRB (11 12 %).

Coverage of the states in the Danube River Basin (DRB) and estimated population

(data source: Competent authorities in the DRB unless marked otherwise)

TABLE 4

Official

Digitally

Percent of

coverage in DRB

determined coverage in

Percentage of DRB

Percentage of DRB

Population in DRB

population in DRB

State

Code

[km2]

DRB [km2]*

[%]

in state [%]

[Mio.]

[%]

Albania

AL

126

< 0.1

0.01

< 0.01

< 0.01

Austria

AT

80,423

10.0

96.1

7.7

9.51

Bosnia i Herzegovina

BA

36,636

4.6

74.9

2.9

3.58

Bulgaria

BG

47,413

5.9

43.0

3.5

4.32

Croatia

HR

34,965

4.4

62.5

3.1

3.83

Czech Republic

CZ

21,688

2.9

27.5

2.8

3.46

Germany

DE

56,184

7.0

16.8

9.4

11.60

Hungary

HU

93,030

11.6

100.0

10.1

12.47

Italy **

IT

565

< 0.1

0.2

0.02

0.02

Macedonia

MK

109

< 0.1

0.2

< 0.01

< 0.01

Moldova

MD

12,834

1.6

35.6

1.1

1.36

Poland

PL

430

< 0.1

0.1

0.04

0.05

Romania

RO

232,193

29.0

97.4

21.7

26.79

Serbia and Montenegro***

CS

88,635

11.1

90.0

9.0

11.11

Slovak Republic

SK

47,084

5.9

96.0

5.2

6.42

Slovenia

SI

16,422

2.0

81.0

1.7

2.10

Switzerland

CH

1,809

0.2

4.3

0.02

0.02

Ukraine

UA

30,520

3.8

5.4

2.7

3.33

Total

(801,463)

100

81.00

100

*

For the purpose of comparison the coverage of the states was calculated using GIS based on the DRBD overview map.

These values differ slightly from the official data of some countries, since other methods of calculation have been used.

**

Data source: Autonomous Province of Bozen South Tyrol.

*** According to the 2002 census the population in Serbia and Montenegro without the provinces of Kosovo and Metohia is 7.668.000 inhabitants.

On the territory of Kosovo and Metohia the last census was in 1981. On the basis of this census and OEBS data the estimated population of Kosovo

and Metohia in the Danube river basin today is about 1.300.000 inhabitants.

The Danube River Basin District and its international coordination arrangements 22

2.3. International coordination of WFD implementation

2.3.1. Coordination at the basin-wide level

and its environment. Austria, Bosnia i Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia,

The Danube River Protection Convention forms the overall legal

the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Moldova, Romania, the

instrument for cooperation and transboundary water management in

Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Serbia and Montenegro, Ukraine and the

the Danube River Basin. The main objective of the convention is the

European Community are Contracting Parties to the DRPC.

sustainable and equitable use of surface waters and groundwater and

includes the conservation and restoration of ecosystems. The

To facilitate the implementation of the DRPC, the Danubian countries

Contracting Parties cooperate on fundamental water management

agreed that with its entry into force the ICPDR is established. The

issues and take all appropriate legal, administrative and technical

ICPDR is therefore the framework for basin-wide cooperation (see

measures, to maintain and improve the quality of the Danube River

Figure 2).

Organisational Structure under the Danube River Protection Convention

FIGURE 2

CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR)

Implementation of Danube River Protection Convention (DRPC)

Decision making, management and coordination of regional cooperation

Approval of the budget and annual work programme

Follow up of activities and evaluation of results from Expert Groups

Joint Action Programme

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Creation of sustainable ecological conditions for land use and water mgmt

Capacity building and reinforcement of trans-boundary cooperation

Strengthening public involvement in environmental decision making

Permanent Secretariat (PS)

Reinforcement of monitoring, evaluation and Information System

Supporting the ICPDR sessions

Supporting the Expert Groups

Coordinating the work programme

Supporting project development and implementation

Maintenance of the Information System

Legal and Strategic

River Basin

Ecology (ECO EG)

Emissions (EMIS EG)

Monitoring, Laboratory

Accident Prevention

Flood Protection

issues (ad-hoc S EG )

Management (RBM EG)

Habitats and species

Emissions from

and Information Mgmt

and Control (APC EG)

(FP EG)

Strategic issues

Integrated river

protection areas

point sources

(MLIM EG)

Accident pollution

Preparation and

Legal issues

basin management

Management of

Emissions from

Trans-National

incidents

implementation of

Administrative and

Implementation

wetlands and

diffuse sources

Monitoring Network

AEWS operation

Action Plan for

financial issues

of the EU Water

floodplains

Guidelines on BAT

Laboratory Quality

Accident prevention

Sustainable Flood

Framework Directive

Assurance

Protection

Cartography and GIS

Danube Black Sea

(RBM/GIS ESG)

Joint Technical WG

Economic Analysis

(RBM/ECON ESG)

The Danube River Basin District and its international coordination arrangements 23

At its 3rd Ordinary Meeting on November 27-28, 2000 in Sofia the

Coordination mechanisms for WFD implementation

ICPDR made the following resolutions:

in the Danube River Basin (for bilateral agreements only

The ICPDR will provide the platform for the coordination necessary to

some examples are shown; a full list is contained in Table 5)

FIGURE 3

develop and establish the River Basin Management Plan for the Danube

River Basin.

The Contracting Parties ensure to make all efforts to arrive at a coordinated

international River Basin Management Plan for the Danube River Basin in

line with the requirements of the WFD.

In the ICPDR all Contracting Parties support the implementation of

the WFD in their territories and cooperate in the framework of the

ICPDR to achieve a single, basin-wide coordinated Danube River

Basin Management Plan. The ICPDR President has addressed

the other DRB countries not cooperating under the DRPC to commit

themselves to cooperate with the ICPDR to achieve a basinwide

coordinated DRBMP. Poland, Switzerland, Macedonia and Albania

have offered their support. From Italy no response was received.

On the operational level, it is the obligation of the Contracting Parties