Addressing Shark Finning in FFA

Member Countries: Issues and

Considerations

November 12, 2006

Mike A. McCoy

GILLETT, PRESTON AND ASSOCIATES INC.

2

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

CITES

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

CPCs

Contracting Parties, Cooperating non-Contracting Parties, Entities

or Fishing Entities

DWFN

Distant Water Fishing Nation

EEZ

Exclusive Economic Zone

ENGO

Environmental non-Governmental Organization

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations

FFA

Forum Fisheries Agency

FSM

Federated States of Micronesia

kg

kilograms

IATTC

Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission

ICCAT

International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas

IOTC

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission

IPOA

International Plan of Action (sharks)

IUCN

International Union for the Conservation of Nature

NAFO

Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organisation

NOAA

National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration

NPOA

National plan of Action (sharks)

PICs

Pacific Island member countries of FFA

RFMO

Regional Fisheries Management Organization

RSW

Refrigerated seawater

SCRS

Scientific Committee on Research and Statistics

TAL

Tropical Albacore fishery

TDL

Tropical Deep Longline fishery

TSL

Tropical Shallow Longline fishery

WCPFC Convention Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly

Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean

WCPO

Western and Central Pacific Ocean

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SUMMARY

4

INTRODUCTION

8

PART 1 BACKGROUND

11

1 The Basis for Shark Fin Demand in Commerce

11

2 Shark Fin Demand and Commercial Fishing in the WCPO

12

2.1 Relative Importance of Shark Fins from Pacific Island Countries

14

3 The Shark Finning Issue Worldwide

16

4 Impetus for Management Action

17

PART 2 SHARK FINNING BAN IMPLICATIONS FOR FFA PACIFIC ISLAND

MEMBERS

20

5 International Legislative Responses to the Finning Issue

20

6 RFMO Approaches to Control of Shark Finning in Tuna Fisheries

21

6.1 Significant Issues in the Existing RFMO Approach

21

7 Current Pacific Island Management Approaches to Shark Finning and Shark

Fishing

24

7.1 Relevant Information on Shark-related Fishery Management in FFA Member

Countries

24

7.2 Pacific Island Fishing Industry Concerns on Shark Finning

26

8. Potential Consequences for Pacific Island FFA Member Countries of

Implementing a Shark Finning Ban by the WCPFC

27

8.1 Summary of Available Information on Shark-related Commercial Activity in FFA

Member Countries

27

8.2 Potential Consequences for the Fishing Industry

29

8.3 Potential Consequences for Fisheries Management in FFA Member Countries

37

9. Potential Consequences for FFA Members of Not Implementing a Shark Finning

Ban

37

10. Conclusions

38

APPENDIX 1 Membership in Regional Fisheries Management Organizations

40

APPENDIX 2 Comparison of RFMO Approaches

42

References

45

4

SUMMARY

Basis for shark fin demand Increased demand in last 20 years for shark fins has been

in commerce

driven by (1) social and political reforms in China that have

not discouraged consumption of shark fin soup as in the

past, (2) relaxation of trade restrictions between Hong Kong

and China that have made it easier and more profitable to

process shark fins in China that are originally exported to

Hong Kong from worldwide sources, and (3) economic

expansion in China, including Hong Kong that has created

an expanded middle class more able to afford high priced

delicacies such as shark fin soup.

Relative importance of

Available Hong Kong trade data from 1998 representing

shark fins from FFA

about 50 percent of total shark fin trade worldwide indicates

Member Countries

that the "Oceania" category represented about 3.4% of

imports into Hong Kong by weight during that year. Of the

seven countries listed in this category, Australia was by far

the largest source of imports. Other areas with significant

exports were Fiji, Samoa, and "U.S. Oceania" (assumed to

be mainly American Samoa).

Impetus for and

Much of the impetus for imposing bans on shark finning has

international legislative

originated with ENGOs. Legislation banning finning now

responses to shark finning

exists in the U.S., Australia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and

the European Union. In the Pacific Islands, the laws of Palau

are the most encompassing, banning the possession of

sharks or any shark body parts onboard foreign fishing

vessels in the Palau EEZ.

RFMO approaches to shark The adoption of a binding recommendation by ICCAT

Finning

concerning shark conservation including a ban on finning

was preceded by four years of discussion and the adoption

of several preliminary non-binding resolutions, including

those to provide information on shark catches and

recommending conducting stock assessments on those

species most commonly caught as bycatch.

The validity of the provision that fins onboard total no more

than 5 percent of sharks onboard is being re-evaluated and

discussed in ICCAT and IATTC.

Only the IATTC binding resolution suggests that parties

"should establish a national plan of action for sharks". ICCAT

and IOTC do not address NPOAs in their shark conservation

recommendations.

ICCAT and IOTC recommendations are specific that parties

shall consider appropriate assistance to developing CPCs for

the collection of data on their shark catches. A similar

provision by IATTC say sit will consider assistance to

developing CPC for collection of data on shark catches,

5

presumably not just catches of the flag state.

Current FFA member

Cook Islands and Vanuatu ban shark finning as a result of

country management

their membership or being a cooperating non-party in one or

approaches to shark

more of the RFMOs. Australia bans shark fisheries in all its

finning

fisheries through domestic law or regulation, as well as being

a member of IOTC. Marshall Islands and Palau have

completed draft NPOAs for sharks.

Pacific Island fishing

In the short term a ban on finning will adversely affect vessel

industry concerns

and/or crew revenue. In the longer term, there is some

concern that finning bans may be only a precursor to

banning all bycatch of sharks and encourage those who

seek a ban on longline fishing.

Shark finning-related

Fiji and PNG are the countries with the greatest commercial

commercial activity in

activity related to shark fins. The 2005 declared value of

Pacific Island FFA member shark fins exported from PNG was US$1.33 million. An

countries

estimate of the overall value of the shark fin market in Fiji is

about US$29 million. FAO statistics rank New Zealand 9th in

the world in shark product exporting countries, at about the

same level as the U.S.

Trends in shark fin

Demand will continue to rise alongside China's economic

demand and utilization

development, unless the popularity of shark fin soup falls. In

the absence of controls placed on fishing, it is likely that

more targeted shark fisheries will develop. It may be that

abundant and fecund blue shark (Prionace glauca)

populations are able to sustain current fishing pressure, but

the resilience of other species is unknown.

Estimates of finning rates

Using observer data from Pacific Island countries held at

and volumes in Pacific

SPC, it is estimated that in the tropical shallow longline

Island longline fisheries

fishery about 11 sharks are finned for every tonne of tuna

caught; about 3.5 sharks are finned per tonne of tuna in the

tropical deep longline fishery, and 4 sharks per tonne of tuna

caught in the tropical albacore fishery.

Using assumptions on dressed shark weights for species

most commonly caught in the Pacific Island longline

fisheries, it is estimated that these rates result in 25 kg of

(wet) shark fin valued at $600 per tonne of tuna in the

tropical shallow longline fishery, 8 kg of fins worth $200 in

the tropical deep longline fishery, and 9 kg of fins worth $225

in the tropical albacore longline fishery.

Potential consequences

It is estimated that the financial losses to domestic PIC fleets

for the Pacific Island

from the inability to fin sharks would be on the order of $8.2

fishing industry of a shark

to $9.6 million. This represents about 6 to 7 percent of the

finning ban

total $137 million value of the longline catch by FFA Pacific

Island member countries in 2005.

Other potential consequences could include:

· Increased value of fin portion of directed shark fisheries,

and a potential switch of vessels in the tuna fishery to

6

targeting sharks if allowed by authorities

· Schemes to collect fins from tuna targeting vessels at

sea to bypass controls placed on finning

· Reduced use of ports by foreign transshipping longline

vessels which would not want to be scrutinized by

authorities enforcing a ban.

Potential consequences

If a ban on shark finning was adopted by the WCPFC that

for Pacific Island fisheries

mirrored language in the other three RFMOs, WCPFC

management of a shark

members could be required to do the following:

finning ban

1. Report all data for catches of sharks by the flag state,

likely to the Scientific Committee.

2. Take necessary measures to require that their fishermen

fully utilize their entire catches of sharks.

3. Require vessels to have onboard fins that total no more

than a percentage (currently 5 percent) of the weight of

sharks onboard.

4. Take the necessary measures to ensure compliance with

the (5) percent ratio through certification, monitoring by

an observer, or other appropriate measures. This would

not be necessary if members required fins and carcasses

to be offloaded together at the point of first landing.

5. Encourage the release of live sharks, especially

juveniles, to the extent possible, that are caught

incidentally and are not used for food and/or subsistence.

6. Where possible, undertake research to identify shark

nursery areas.

Potential consequences of

An increase in the pressure on FFA members and continued

not implementing a shark

pressure on WCPFC as a whole can be expected from

finning ban

ENGOs that desire a ban on shark finning.

The U.S. will likely rely on both formal and informal

diplomatic efforts to convince FFA member countries to

adopt a ban. The U.S. Shark fin Prohibition Act requires that

the U.S. government "seek agreements calling for an

international ban on shark-finning and other fishing practices

adversely affecting sharks... through the appropriate

regional fishery management bodies".

Protracted discussions could see the emergence of regional

or worldwide efforts to boycott fisheries that are perceived to

be not acting responsibly by continuing to allow shark

finning. If such boycotts eventuate, it is more likely to come

from ENGO sources than through government trade

sanctions.

Conclusions

Understandably, with many other issues to contend with,

there has not been much attention paid to shark finning by

fisheries administrators in the Pacific Islands. They will have

to address this issue at some point, as a shark finning ban

has already been adopted by other RFMOs and is now on

the agenda of WCPFC.

7

The impetus for adoption of a shark finning ban by WCPFC

will continue, with ENGOs and the U.S. providing most of the

pressure to do so within the WCPFC context.

The three RFMOs have not taken identical paths to adoption

of shark conservation measures, with the ICCAT example

being the most deliberate. The ICCAT case may offer some

guidance to FFA members uncomfortable with enacting a

ban now and accepting the management tasks required.

The FFA Pacific Island member countries that would be most

adversely affected by a ban on shark finning are Fiji and

Papua New Guinea, with the financial impact being the

greatest in the former.

The foregone revenue from shark finning to domestic fleets

in these two countries, while relatively small in comparison to

the overall value of the catch, will place additional financial

hardships on vessel owners and operators already

concerned with increasing costs of operation, including

higher fuel and air freight prices.

8

INTRODUCTION

Background to the Study

The subjects of sharks and shark finning have been on the fisheries management

agenda in Pacific Island countries for a relatively short period. The activities leading up

to and subsequent adoption of the Food and Agriculture Organization's Code of Conduct

for Responsible Fisheries (1995) and International Plan of Action-Sharks (2000) have

been two of the more visible activities that have brought the subject to the fore in recent

years.

Beginning in late 2005, discussions were held during meetings of the Western and

Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) on the possibility of the Commission

adopting a statement that would address shark conservation and include shark finning1.

The U.S., then and now not yet a member of WCPFC, circulated a document identical or

similar to one that they had strongly supported in the Inter American Tropical Tuna

Commission and which that organization had adopted the previous June.

At the last meeting of the WCPFC Commission in late 2005, it was decided that due to

the substantial work required before considering action on shark conservation, including

shark finning, the matter would be deferred until the upcoming third regular session of

the Commission.

FFA determined that the decision taken to defer provided the opportunity to undertake a

detailed study of the issues associated with shark finning. This would enable further

discussion among FFA members and an examination of the potential consequences for

member countries adopting or rejecting a shark finning ban, should such an action be

proposed.

As a result, FFA hired a consultant to undertake what was essentially a desk study

addressing shark finning in the Pacific Islands. The objectives of the study were to (1)

determine to the degree possible the current situation with regards to shark finning in

commercial tuna fisheries in Pacific Island countries, and (2) examine the implications of

the possible implementation or rejection of a ban on shark finning by the WCPFC. This

report is the result of that study.

Purposes of the Study

The purposes of this study as described in the consultant's terms of reference are to

provide advice to FFA Members on:

a) Shark fining practices in the WCPO, including quantification of the removal of

shark fins and the discarding of carcasses, and the increased incentive to exploit

shark species as a result of the expansion of shark fin markets;

b) The potential impacts on FFA Members of implementing measures that

prevent the removal of shark fins where carcasses are dumped;

c) The potential impacts on FFA Members of not implementing measures that

prevent the removal of shark fins where carcasses are dumped; and

1 The WCPFC Convention applies to shark species listed as highly migratory in Annex 1 of the United

Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

9

d) The applicability of individual FFA Member county NPOA-Sharks to the issue

of the removal of shark fins where the carcass is dumped.

Methodology

As noted, this report is the result of what was primarily a desk study. Travel was

undertaken to Manila from 4-8 August, 2006 to present the project to FFA

representatives gathered to attend the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries

Commission's Scientific Committee meeting. The trip afforded an opportunity and to

meet with FFA country representatives to elicit available shark finning-related

information. A brief side-trip was also taken to Palau from 9-12 August to interview

government officials, dive tour operators, ENGOs and longline fishing industry

representatives. Palau was chosen as an important venue for research because of its

stringent ban on shark finning and possession of sharks by foreign fishing vessels within

its Exclusive Economic Zone.

Organization of the Report

The report is divided into two main sections: a background section that provides

information useful to further understanding of the use and market for shark fins, and an

explanation of how market demand applies to PIC fisheries.

The second section addresses the implications for PICs of a shark finning ban.

International legislative responses to the shark finning issue are reviewed, followed by

the approach taken by RFMOs.

The second section also describes current PIC management approaches to sharks and

shark finning, as well as setting out the concerns of some operators in PIC domestic

fleets.

Within section two, potential consequences for PICs in implementing a shark finning ban

by the WPFC are presented. The first part describes possible impacts, including financial

impacts, on the domestic longline fishing industry. The second describes the

consequential actions from a finning ban that might be required of PIC fisheries

management.

The potential consequences for PICs of not implementing a shark finning ban are then

analyzed. A final section draws some conclusions from the information presented.

Terminology and Abbreviation Usage

A list explaining the use of acronyms and abbreviations appears at the beginning of this

report. The use of the term shark finning ban rather than shark finning measure

throughout the report is intentional, because measure might be seen to be one of a

hierarchy of terms applying to binding or non-binding agreements by RFMOs.

All values quoted in dollars are in U.S. dollars unless otherwise specified. Quantities

expressed in tonnes are metric tonnes. Use of the term "Pacific Island countries" or

PICs refers to Pacific Island FFA member countries except when stated otherwise.

10

Acknowledgements

In spite of the fact that the subject of shark finning can be somewhat of a sensitive issue

in some PICs, the consultant was accorded cooperation by those government fisheries

officials, vessel operators and industry representatives contacted in person and by

telephone. Representatives of ENGOs and the dive tour industry in Palau were open

and articulate in explaining the reasons for their concerns over shark fishing. Thanks

are due to all those contacted, in particular Michael Batty of FFA, Nannette Malsol of

Palau's Bureau of Marine Resources, Peter Ward from the Australian Bureau of Rural

Sciences, and Matthew Hooper of the New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries.

11

PART 1 BACKGROUND

1 The Basis for Shark Fin Demand in Commerce

Shark fins have been described as one of the most expensive fish products in the world

(Vannuccini 1999). They serve but one culinary purpose: the source of the primary

ingredient in shark fin soup, a delicacy that is consumed by Chinese and east Asian

communities, primarily in east Asia and but also worldwide2.

Chinese references point to records of the consumption of shark fin soup in China as far

back as the Sung dynasty, 960-1279. By the 14th century shark fin soup was established

as a traditional component of formal banquets (Clarke 2003). Literature on the subject

generally ascribes the historical use of shark fin soup (along with other specialties such

as birds' nest soup) to the quest by emperors and noblemen to locate exotic and health

promoting food. One interpretation of the high value placed on the product comes from

the fact that only a small quantity of the main ingredient can be obtained from a large

fish. As such, the fins were said to be noble and precious, qualities that made them fit for

the tables of emperors (Rose 1996). Over time, consumption of shark fin soup evolved

to where it was served in China mainly at dinner parties, weddings or banquets to

express the host's respect for his guests. According to Vannuccini (1999) the benefits of

shark fin as documented by old Chinese medical books include rejuvenation, appetite

enhancement, nourishing to blood, beneficial to vital energy, kidneys, lungs, bones and

many other parts of the body.

Shark fin soup is not made from the entire fin, but rather uses the ceratotrichia (usually

referred to in English as fin needles or fin noodles). The needles consist of the slender

golden colored fibers that lie between the cartilage within the fins found in many (but not

all) species of shark. These fin needles run in parallel and radial to the fin base,

supporting the web of cartilage within the fin itself.

The southern provinces of mainland China, primarily Guangdong and Fujian, are said to

have been the centers of shark fin culinary development where the technique was

developed of removing the fibers to produce "chi pian" or fin cakes used in the

production of the soup (Clarke 2003). Since the needles do not have any flavor

themselves, chicken stock or other ingredients are added to impart flavor to the soup.

The needles are separated from the cartilage during a laborious process that involves

cleaning and skinning of raw fins, boiling, removing fin ray membranes, bleaching, and

drying in multiple and differentiating steps which produce a variety of final product forms.

The most important traits of ceratotrichia in valuing shark fin from different species are

their thickness and length. Shark fins that yield long, thick fin needles are those that

command the highest prices (McCoy and Ishihara 1999).

During the Maoist era in China during the twentieth century, the consumption of shark fin

soup was limited as officials frowned upon its use and viewed it as an elitist food.

Beginning with China's reform policies instituted in 1986, changes took place removed

2 The Chinese communities in such places as Thailand and in North America (primarily New York, San

Francisco and Vancouver) also represent considerable (if unquantified) groups of consumers that provide

markets for shark fin outside of Asia.

12

this stigma and consequently increased the volume and manner of consumption that

have affected trade in shark fin that has continued until the present.

The reforms in China also allowed the establishment of shark fin processing operations

in southern China, making it possible for Hong Kong to both avail itself of cheaper labor

for fin processing and open up new markets, particularly in the booming southern China

region. The Hong Kong economy also greatly expanded during this period resulting in a

greater popularization of shark fin soup. One author described the Hong Kong situation

in the mid-1990s:

Whereas shark fin used to be a high-priced delicacy found in only expensive

shark fin restaurants, there are now many smaller restaurants specializing in

shark fin soup, and importing and processing their own shark fins. This

popularization of shark fin has made shark fin soup more accessible as it is now

possible to eat shark fin soup at a more reasonable price and during more casual

occasions; in the past, shark fin was consumed by those of lower economic

status only during formal banquets (Parry-Jones 1996)3.

Since the 1990s, continued economic expansion in mainland China has resulted in a

larger middle class that has also increased the demand for shark fin. This demand has

been transmitted to existing fisheries by traditional fin dealers and others. Attractive

prices have in turn fueled increases in the targeting of sharks, primarily for their fins. In

many cases there is a discarding of the carcass at sea and retention of the fins only, a

practice referred to as "shark finning".

2 Shark Fin Demand and Commercial Fishing in the WCPO

At least one author well-versed in the current shark fin trade has stated that it is likely the

volume of whole sharks landed by fishing vessels around the world once provided

sufficient fins to supply the fin markets of east Asia and east Asian communities

worldwide (Watts 2003).

That whole sharks landed by fishing vessels once provided sufficient fins to supply key

markets is debatable, at least in the last 40 to 50 years in an era of industrial longlining

in the WCPO. Shark fins have been collected through finning on tuna longline vessels in

the WCPO for many years. Up until recently in many Pacific Island ports it was not

uncommon to see drying shark fins hanging from the rigging of Asian longliners that did

not retain shark carcasses and had obtained the fins through finning4.

Up until the last 10 years or so the income from shark fins obtained through finning

formed a traditional portion of the crew's remuneration, often characterized as a bonus

or spending money for periods ashore. Increased demand resulting in higher fin prices

have no doubt encouraged the finning of sharks that might otherwise have been struck

off as either a nuisance or danger to fishermen onboard. The high fin prices have also

3 It should be recognized that there are numerous levels of quality in the ingredients preparation, and

presentation of shark fin soup. A bowl of soup can be purchased for as little as $5 in some restaurants, with

various flavorings added. At more exclusive restaurants, the cost (and presumably the quality) could easily

be fifteen to twenty times that figure.

4 Such fins, while still collected, are often now placed out of sight onboard longliners in port. This may be

because of sensitivities towards the issue of longlining, but also because it may invite thievery given their

current value.

13

altered the manner in which revenue is distributed in some fleets, contributing a greater

percentage to vessel revenue and less to crew bonuses than in the past.

Fins are typically sold in sets taken from the same shark. The primary fin set consists of

the dorsal fin, both pectoral fins, and the lower lobe of the caudal fin. The upper lobe of

the caudal is usually not retained, because in most species it does not contain the

ceratotrichia required for the end product. Other, smaller fins can also be retained and

are sold at a lower price as `chips'.

The increase in demand began in the mid-1980s as noted above. It has resulted in many

diverse sources of shark fins serving the markets in Hong Kong, Singapore, mainland

China and elsewhere. The fisheries supplying these markets are geographically and

technologically varied, and can be characterized as:

· fisheries directed at sharks, mostly gillnet or longline fisheries,

· bycatch from other fisheries such as tuna longline, tuna purse seine, and shrimp

and groundfish trawling, and

· Artisanal fisheries using relatively unsophisticated fishing gear

For vessels operating in these categories, sharks can be:

· stored onboard whole with fins attached,

· partially processed onboard with head, guts discarded, fins removed and the

resultant trunk and fins valuable in commerce retained, or

· discarded at sea with only the fins valuable in commerce retained.

The first category describes the situation that is most likely to occur in small-scale

artisanal fisheries, for example small-scale gill net fisheries where the catch is simply

taken onboard rolled into the net with which it was captured and dealt with ashore.

Except where required by law or regulation, it is usually not the practice to store whole

sharks onboard larger vessels such as industrial longliners because too much valuable

space in the fish hold is used.

The second category describes what happens to some (but not necessarily all) of the

catch by shark targeting and tuna-targeting fleets.

The third category, finning, takes place in tuna-targeting longline and purse seine

fisheries due to a combination of two major factors:

(1) there is increasing demand for shark fins, and

(2) the economics of catching and transporting fish products (including sharks)

often make it impractical/undesirable to retain more than the fins onboard.

The limited storage onboard many tuna-targeting longline vessels makes it

uneconomical to retain anything other than the fins from most sharks. Fins are by far the

most valuable part of the shark, and low prices or non-existent markets for shark meat

discourage further retention.

Even if markets could be found for shark meat, certain biological characteristics make it

unlikely that tuna vessels would take the time to properly handle and store sharks caught

14

by longline. Unlike teleosts, sharks have a large amount of urea in their meat as a result

of possessing a more primitive kidney system. When a shark dies, urea is converted to

ammonia. Proper handling and storage to preserve good quality meat onboard takes

time, and at least for now the returns do not justify the expense for most species. Even

on those large, distant-water longline vessels with sufficient storage space, only shortfin

mako shark trunks are retained as that is the one species with a market value high

enough to justify the freezing, storage, and handling required to bring the catch to

market5.

Trends in shark fin demand and utilization are important to identify in considering fishery

management responses. An author who has studied the shark fin trade extensively in

Hong Kong and elsewhere has been quoted as anticipating the following trends for the

shark fin trade:

Consumers: demand will continue to rise alongside China's economic

development, unless the popularity of shark fin soup falls

Producers: in the absence of controls placed on fishing, it is likely that more

targeted shark fisheries will develop

Species: it may be that abundant and fecund blue shark (Prionace glauca)

populations are able to sustain current fishing pressure, but the resilience of

other species is unknown (CITES 2006)

2.1 Relative Importance of Shark Fins from Pacific Island Countries

Once fins from sharks enter commerce, government statistics and available data do not

differentiate between species, even though biological differences between species as

well as morphometric differences play a large role in determining fin price.

Overall, it is believed that the total contribution of shark fins from the Pacific Islands has

been marginally significant in world trade, and much smaller than that from other

geographic regions. One source estimated the volume of dried shark fins from "Oceania"

to Hong Kong at about 105 metric tons in the first 11 months of 1998 (Figure 1), or about

3.4% of total Hong Kong imports for that period (McCoy and Ishihara, 1999).

5 The practice (sometimes referred to as high grading) of discarding a portion of the catch for economic

reasons is also sometimes employed with the target species; for example when smaller tuna retained during

the early stages of a trip are discarded to make room for larger or better quality fish later.

15

Figure 1 Hong Kong Imports of Dried Shark Fin

By Geographic Region, Jan. Nov. 1998

)

s 800

n 700

t

o

600

t

r

i

c

500

e 400

(

m 300

r

t

s 200

o

p 100

I

m

0

sia

sia

erica

A

erica

frica

E

A

A

cean

S

E

id-East

ceania

m

O

orth Am

N

South Am

Indian O

Source: Hong Kong Agriculture and Fisheries Department, unpublished data

Cited in McCoy and Ishihara (1999)

Hong Kong is the most important market in world trade for dried fins but is by no means

the only one. Singapore is also important because of its geographic location and large

ethnic Chinese population.

Taiwan is a significant market for wet (i.e. frozen) fins produced by local and distant

water Taiwanese fishing fleets.

Of the seven countries contained in the Oceania category in Hong Kong statistics,

Australia was by far the largest source of imports during the period with 53 metric tons or

50% of the total. Figure 2 depicts the relative volumes from the various countries

comprising the Oceania category in Hong Kong statistics.

Figure 2. Hong Kong Imports of Dried Shark Fin from Oceania,

JanuaryNovember 1998

)

s 60

n 50

t

o

40

t

r

i

c

e 30

20

(

m

10

r

t

s

o

0

p

I

m

US

W.

Australia Solomon

Fiji

New

Papua

Oceania

Samoa

Islands

Zealand

New

Guinea

Units: metric tons; Figures are rounded to nearest metric ton

Source: Hong Kong Agriculture and Fisheries Department, unpublished data, cited in McCoy

and Ishihara (1999)

16

Figure 2 is represents only dried shark fins, and not "wet" or frozen fins usually landed

by Taiwanese or domestic longliners in the Pacific Islands. Pacific Island countries that

may be significant sources of wet fins include Fiji, PNG, Marshall Islands, and (in the

past) Solomon Islands. These wet fins may be exported frozen to Taiwan as is done by

the shark targeting fleet in PNG, or partially processed onshore as might be the case in

Fiji, and sent to markets including Hong Kong.

Recent estimates of world trade in shark fins in 2000 put the figure of the trade

worldwide at 11,602 tonnes, and Hong Kong's portion of that trade at around 6,800

tonnes or 59% (Clarke et al. 2006)6.

3 The Shark Finning Issue Worldwide

With little scientific data on the levels of shark finning worldwide, most of the information

on shark finning available to the general public in developed countries is contained in

popular literature, much of which is used to drive efforts to ban finning. In much of this

literature it is often difficult to separate the issue of finning from that of shark

management in general.

Information and awareness campaigns, usually conducted by well-funded environmental

groups, often fail to make the distinction between shark conservation in general, the

management of sustainable shark fisheries, and the specific finning issue. Finning can

be presented in such a way as to taint all rational fisheries management arguments

concerning sharks, and this can cause problems for fisheries managers.

One way to describe finning in an international tuna management context is to view the

practice as:

increasing overall shark mortality by expanding the opportunities to retain only

the most valuable portions of the animal in situations where it might otherwise be

avoided or struck off the line before landing.

In the press and elsewhere the practice of finning is often linked to wastage and

described as a wasteful practice7. Minimizing waste in fisheries is a prominent feature of

the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries developed in 1995, and the concept

has been adopted as relevant in the subsequent FAO International Plan of Action for

Sharks (IPOA).

A second, often more extreme linkage is made by some ENGOs between shark finning

and animal cruelty. Examples of such linkage can be found in the statements on the

worldwide websites of various shark and animal welfare groups: "the brutal business of

shark finning" (Sea Shepherd Society); "horrible death for a magnificent creature" (Shark

Friends); "wasteful and often cruel practice (Shark Trust) and so on. This connection can

also find its way into legislative interpretations. In New Zealand, for example, it is not

6 This figure represents fins in a dried state, and is based on national customs statistics and adjusted for

observed underreporting for Mainland China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and Japan relative to Hong

Kong as an importer.

7 It is seldom noted in the popular literature and information concerning finning that waste in fisheries

originates as an economic issue, and finding economic uses for discards doesn't necessarily solve the

management problem. In fact, it can exacerbate it.

17

illegal to fin dead sharks under current fishery regulations but it is illegal to fin a live

shark under New Zealand's Animal Welfare Act.

The countries in Asia that serve as markets for shark fin have recently been the targets

of publicity campaigns by ENGOs in Asia which are focused on educating the consumer

and campaigning against the consumption of shark fin soup. These continuing efforts

are gaining momentum in several of the shark fin consuming countries, notably

Singapore and China (Hong Kong).

WildAid, one of the more prolific and financially well-endowed groups engaged in anti-

shark fin efforts, has enlisted the assistance of movie stars such as Jackie Chan in Hong

Kong to campaign against the consumption of shark fin soup. Most recently, WildAid

introduced a Chinese basketball star in the U.S., Yao Ming, as well as a Chinese pop

singer as their spokespersons in China campaigning against the consumption of shark

fin soup8.

It is the position of WildAid and some others engaged in efforts to reduce or eliminate

consumption of shark fin that the key to success is self-restraint practiced by consumers.

These groups believe that finning bans will not work and that the way to stop finning and

reduce shark mortality in general is to approach it from the demand, as opposed to

supply, side.

There has been some success in these campaigns in Asia. In June, 2006 Hong Kong

Disneyland removed shark fin soup from its menus at the theme park. A few months

later, Hong Kong University decided to discontinue serving shark fin soup at official

functions and banquets sponsored by the University.

One of the reasons, given in private and usually not in public pronouncements, by

groups and individuals engaged in the campaigns to reduce demand is that unless

consumer attitudes are changed and demand is eliminated or significantly weakened,

finning bans may only initially reduce supply. This will result in the commodity becoming

even more valuable, expanding illegal fisheries and attracting criminal activity9.

4 Impetus for Management Action

An important point for fisheries managers in the Pacific Islands to consider is that unlike

the controls placed on tuna fishing in the WCPO10, the impetus for banning shark finning

in the WCPO and elsewhere has rarely come from fisheries management personnel. A

review of the brief history of anti-shark finning campaigns and a perusal of the existing

popular literature and information disseminated by those groups engaged in anti-shark

finning campaigns reveals an approach that should not be ignored.

There has been a close working relationship and linkage between some shark

specialists and others engaged in shark research with conservation and environmental

8 While this activity was given publicity in many western countries, it was more or less ignored in mainland

China, and Yao Ming was criticized in China by those who did comment as being insensitive to his own

culture.

9 It is recognized that some criminal elements are already present in shark fin commerce, usually lower in

the supply chain where there can be strong competition for fins from fleets based in some locations. Murders

or attempted murders reportedly linked to shark fin commerce have been reported in South Africa, Honolulu,

Fiji, and San Francisco in recent years.

10 Examples are the early limits on purse seining by the Nauru Group and current FFA approaches to effort

limitation, as well as the negotiation of the UN Fish Stocks Agreement and the WCPFC Convention itself.

18

non-governmental organizations (ENGOs). Both groups have a desire to ban finning and

better manage and control shark fishing, with some wanting to curtail such fishing all

together. These partnerships, in the case of shark finning, tend to bypass fisheries

management agencies and rely on public sentiment to galvanize lawmakers to adopt

legislation banning shark finning.

An example of this strategy is the marshalling of public anti-finning sentiment during the

late 1990s that culminated in banning of shark finning in Hawaii and elsewhere

throughout the US where it was not already prohibited. Whereas ENGOs and activist

shark specialists joined forces and succeeded in getting shark finning outlawed on all

U.S. fleets and within the U.S. EEZ by 2001, fishery managers were generally reactive to

the issue, rather than pro-active in many cases.

In the U.S. case, pressure from well-financed ENGOs was exerted in the media, through

lobbyists and environmental groups in Washington DC and elsewhere that resulted in

the passage of a very strong law, the U.S. Shark Finning Prohibition Act. This law,

among other provisions, requires the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service to initiate

discussion with other nations to develop international agreements on shark finning and

shark catch data collection (NOAA 2005).

These two potent forces, shark specialists and ENGOs, can apply pressure directly to

governments in the developed world which then in turn react nationally (as in the U.S.

case), and internationally. On the international level, efforts have culminated at the Food

and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) with its adoption in 1999 of an

IPOA to serve as a guide to individual countries in the formulation of National Plans of

Action for sharks (NPOA). The IPOA directs NPOAs to implement the relevant sections

of the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries and "minimize waste and

discards from shark catches", and suggests doing so by "requiring the retention of

sharks from which fins are removed" (FAO 2006).

Further efforts by ENGOs are manifested in attempts to get governments to agree to

place certain shark species on lists of protected species covered by the Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and elsewhere.

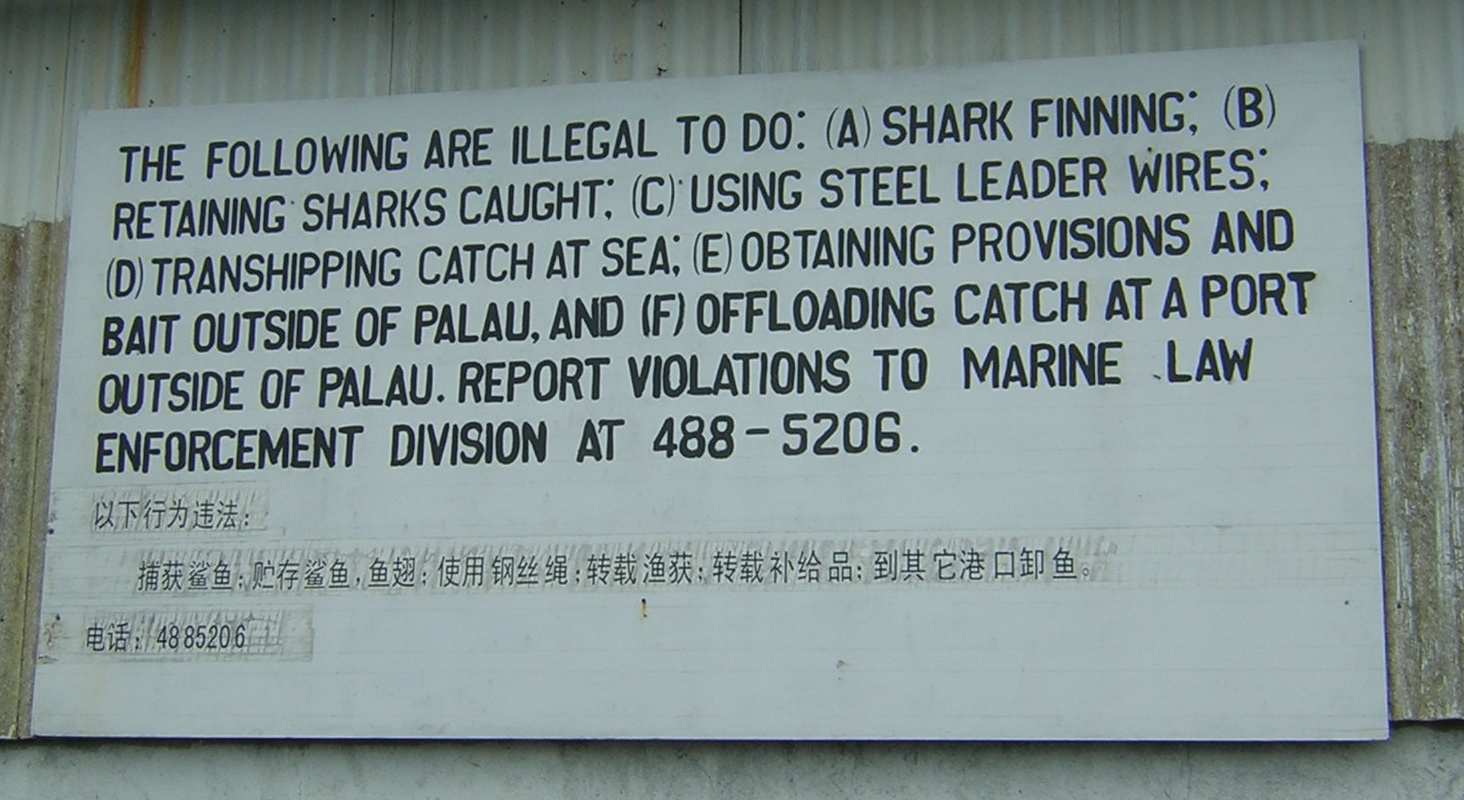

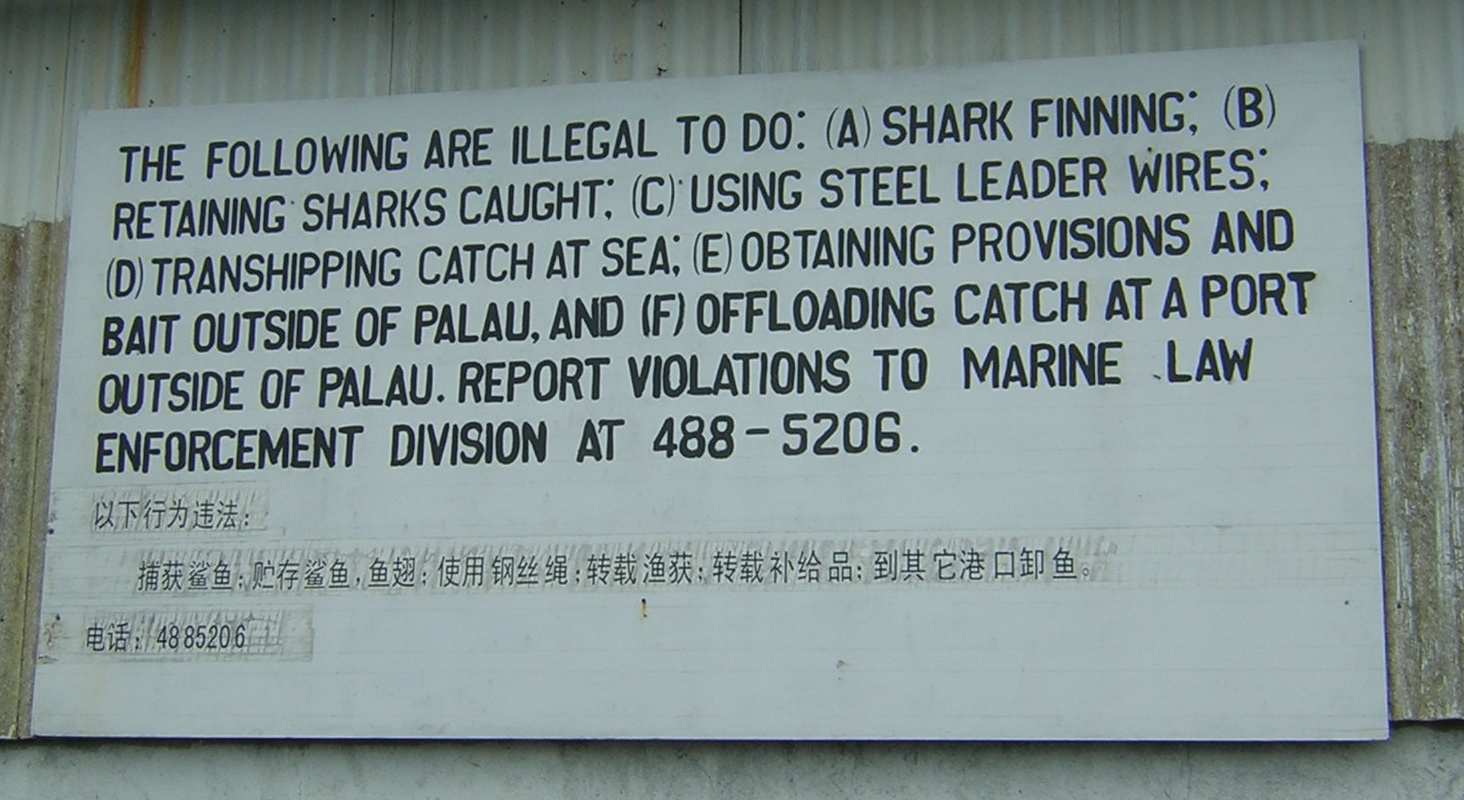

A notable effort that further illustrates the ability of local ENGOs to sway public policy is

the situation in Palau. There, efforts by ENGOs and the Palau-based local dive tourist

industry resulted in passage of the most stringent anti-shark finning and anti-shark

fishing laws in the Pacific (and perhaps anywhere). Figure 3 shows a billboard posted at

the wharf where longline vessels offload. The billboard was required to be posted by the

fishing company as one the settlement terms resulting from a court case against one of

the company's vessels for possession sharks. The company was required to post a

similar billboard in the Bahasa Indonesia language.

ENGOs in Palau continued their activities after the passage of these laws with much

broader goals in mind. One created a "Palau Shark Sanctuary Fund" with the stated

objective of achieving a declaration by Palau that would establish all waters within

Palau's EEZ as a World Shark Sanctuary. This ENGO and others promote Palau Shark

Week for dive tourists, while another conducts "Project S.A.V.E." (Shark Awareness

Visitor Education).

The acceptance by governments of efforts by ENGOs to globally ban the practice of

shark finning has not been universal, however. Many countries continue to allow the

practice, and even where nominally banned through membership in an RFMO,

government policy tends to reflect more deliberate approaches. For example, a

statement by Japan to a reservation on a shark finning resolution passed by the

19

International Union for the Conservation of Nature at the 2004 World Conservation

Congress in Bangkok, Thailand. At that meeting, as part of their objection the Japanese

Ministry of Foreign Affairs provided the following statement for the record:

The key point of (the) shark conservation issue is that fishery activities that only

target shark fins are deteriorating shark resources. We have to recognize that a

ban on finning without identifying species and areas with a real problem will

never lead to a real conservation and management of shark resources.

Figure 3 Billboard at Malakal Fish Wharf

20

PART 2 SHARK FINNING BAN IMPLICATIONS FOR FFA PACIFIC ISLAND

MEMBERS

Sharks are acknowledged to present formidable obstacles to fisheries managers, either

in directed fisheries or as bycatch. As noted by FAO (2006), sharks are known to have a

close stock-recruitment relationship, long recovery times in response to overfishing and

complex spatial structures. Conservation and management of sharks is also impaired by

the lack of accurate data on catch, effort, discards, and trade data, as well as limited

information on the biological parameters of many species and their identification.

For a variety of reasons, sharks have not received much attention from most Pacific

Island fishery managers when focusing on industrial tuna fisheries. The value of shark

landings by tuna-targeting vessels has historically been far below that of target tuna

species and attention has naturally been focused on the target catch which, for many

PICs, is directly linked to levels of access fees paid by distant water fishing nations

(DWFNs). When faced with a multitude of priorities relating to the target tuna catch, it is

not surprising that often understaffed fisheries departments have not focused extensively

on the collection of catch, bycatch, discard and landing data for sharks, all of which are

necessary to enable informed management decisions. There are exceptions, with Papua

New Guinea standing out as one FFA member country that has a shark management

plan in place with a total allowable catch. PNG compiles data on exports of sharks and

shark fins by a directed fishery but does not apply the same scrutiny to domestic

longliners targeting tuna.

Likewise, the subject of shark finning has not been the focus of most fisheries

departments in the Pacific Island region. It is known that several countries, Solomon

Islands being one, licenses shark fin exporters. Others however, such as the Marshall

Islands and FSM, do not require export data to be declared and essentially have no hard

data on the value or volume of shark fins exported.

5 International Legislative Responses to the Finning Issue

The mainly ENGO-led campaign against shark finning over the last ten years or so has

resulted in responses from national governments, RFMOs and other management

bodies that have been nothing short of remarkable.

Legislation or regulatory measures to ban shark finning has now been adopted by the

U.S. and Australia, as well as by Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and the European Union.

In the Pacific Islands region, one of the more extreme sets of measures taken by any

country has been that taken by Palau. In September, 2003, the President of Palau

signed a comprehensive law passed by that country's legislature that prohibits foreign

fishing vessels in Palau's waters from fishing for sharks, or possessing onboard sharks

or any parts of sharks, including fins. The law also bans the use of wire leaders (traces)

in longline gear.

As described above, the impetus for Palau's legislative stance on the issue of shark

finning (and on foreign vessels capturing or possessing sharks) stems primarily from the

ENGOs and private sector promoting the importance of tourism, including dive tourism,

in the Palau economy. Although pelagic sharks caught incidentally to longline fishing in

21

the Palau Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) are usually not those viewed by dive tourists,

the country's strong tourism sector wants to project the image of the country as

containing a pristine oceanic environment. Publicity given Palau's anti-shark fishing and

anti-shark finning laws, as well as a public burning of confiscated fins in 2004 has helped

promote eco-tourism in the country, according to dive tour operators interviewed in

August, 2006 as part of the research for this study.

6 RFMO Approaches to Control of Shark Finning in Tuna Fisheries

In the current management environment surrounding implementation of the Convention

on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western

and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPFC Convention), the approaches taken to shark finning

by other regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) are of major interest to

FFA member countries.

There are three other RFMOs involved with the management of tuna fisheries that have

recently addressed the issue of shark conservation, including the subject of finning: the

Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC), the International Commission for the

Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), and the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission

(IOTC). Each of these bodies has adopted either a resolution (IATTC and IOTC) or

recommendation (ICCAT) on the conservation of sharks that includes clauses aimed at

curtailing and eliminating the practice of shark finning11.

A list of member countries and cooperating non-members of these three organizations is

shown in Appendix 1. The three RFMOs adopting controls over shark finning represent a

total of 58 countries (including the EU as one member). Of these, 13 are either current

members or observers of the WCPFC Commission12.

It is perhaps not surprising that given some of the overlapping membership in the three

organizations which have already addressed the issue and the fact that each has as its

mandate the management of tuna fisheries, the adopted resolutions and

recommendations are very similar in their wording. Appendix 2 provides a comparison

between the relevant language contained in the documents addressing shark

conservation that have been adopted by the RFMOs.

6.1 Significant Issues in the Existing RFMO Approach

6.1.1 Steps Taken Prior to Adoption of Controls

In considering possible courses of action for FFA member countries in the WCPFC on

the subject of shark conservation and shark finning, it is useful to review the steps taken

by one RFMO prior to adoption of controls over shark finning.

11 A fourth RFMO that does not manage tuna but which has adopted control over shark finning in 2004 is the

Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organisation (NAFO).

12 Australia, Canada, China, Chinese Taipei, Cook Islands, European Community, France, Indonesia,

Japan, Korea, Philippines, United States, and Vanuatu.

22

ICCAT was the first of the three bodies to act on the subject of shark conservation,

adopting its recommendation on the final day of its meeting in November, 2004. The

IATTC resolution13 was subsequently adopted in June, 2005. The IOTC resolution was

likewise adopted in 2005, but the exact date is not clear.

The adoption of the ICCAT binding recommendation concerning the conservation of

sharks was preceded by at least four years of discussion on the subject of sharks, and

the adoption of earlier and related resolutions14.

· In 2000, the ICCAT Standing Committee on Research and Statistics

recommended ICCAT take the lead in conducting stock assessments for 3

species of shark

· In 2001, ICCAT adopted a non-binding resolution on sharks. This included

measures for improved data collection for pelagic sharks, and directed that stock

assessments for shortfin mako and blue sharks be conducted in 2004. Other

aspects provided for the release of incidentally caught live sharks and the

minimization of waste and discards (both of which appear in the 2004

recommendation).

· In 2003, a further resolution was adopted that required ICCAT parties to (1)

provide the Bycatch Working Group with information on shark catches, effort by

gear type, landings, and trade of shark products, and (2) fully implement an

NPOA in accordance with the FAO IPOA for sharks.

· In June, 2004 stock assessments were conducted by the Subcommittee on

Bycatch for two species of sharks.

· The recommendation was then formulated and adopted in November, 2004

(NOAA 2005)

It does not appear that the other two RFMOs, IATTC and IOTC, have taken the more

deliberate approach as did ICCAT. There may have been general agreement in the

former two organizations that since key parties agreed to the approach in ICCAT, they

would not object to similar wording in the RFMOs that followed ICCAT's lead.

6.1.2 Analysis of Certain Provisions Contained in Resolutions and

Recommendations

The adopted resolutions and recommendation of the three RFMOs contain certain

provisions that should be examined carefully.

Research directives: It is believed that as shown above, only ICCAT preceded the

adoption of its recommendation with steps intended to better define the conservation

and management problems addressed. The IATTC resolution directs the Commission to

provide preliminary advice on stock status of key shark species and propose a research

plan for a comprehensive assessment of these stocks. The IOTC resolution directs its

Scientific Committee (in collaboration with the Working Party on Bycatch) to do likewise.

13 In IATTC, resolutions are binding, recommendations are non-binding. Both are approved by consensus

(Meltzer 2005a).

14 In ICCAT resolutions are non-binding. Binding Recommendations are adopted by a simple majority vote

with a quorum of two-thirds of Contracting Parties, and enter into force 6 months later (Meltzer 2005b).

23

The "5 percent" debate: Each RFMO requires that fins onboard a vessel should not total

more than 5 percent of the weight of sharks onboard, up to the point of first landing. This

number, 5 percent, has and continues to be a subject of debate within and outside the

RFMOs concerned15. The 5 percent limit has its origins in the U.S. management of its

own longline fisheries on the East Coast of the United States. In 1993 the use of 5

percent as a measure of the weight of the fins compared to dressed carcasses onboard

was introduced in a Fisheries Management Plan on the basis of a very small sample of

just one species, sandbar shark, Carcharhinus plumbeus (Cortes and Neer 2005)16.

Some fishing industry representatives have argued that the number should be higher

than 5 percent on the basis of the species, sizes and manner of dressing sharks. In the

U.S. this argument is made for directed shark fisheries, while in other countries it is

made for sharks that are captured as bycatch in tuna fisheries. Concerns of some

industry representatives of having to meet the 5 percent figure as a measure include (1)

the potential for significant financial loss and (2) exposure to prosecution if 5 percent is

not an accurate depiction of fin-to-body weight representative of the catch in a particular

fishery.

ENGOs are concerned that increasing the number above 5 percent will enable more

sharks to be killed for their fins, and some ENGOs have argued that the number should

actually be lowered. It is noteworthy that each of the RFMO resolutions and

recommendation contains a clause that this aspect should be reviewed, during 2005 in

the case of IOTC and 2006 for IATTC and ICCAT.

Interestingly, there is little information available on the specific situation where carcasses

are retained in a frozen condition while fins are dried. In this situation, the weight of fins

at 5 percent of the weight of carcasses onboard would represent more sharks than

simply those onboard.

The banning of the use of wire traces/leaders: Only the IOTC resolution contains a

provision suggesting that wire traces be included in research to make fishing gears more

selective. Some vessel captains claim that the use of wire traces is to minimize the loss

of large tuna that can cut monofilament leaders when entangled under the gill plate.

Conversations with a vessel operator and an SPC Masterfisherman during the research

for this study indicate that, while wire traces can increase the numbers of sharks landed

by minimizing the times when the trace or leader is severed, some of the newer

monofilament lines used as trace material can have a similar effect. It should also be

pointed out that hook type is a factor in the retention of sharks on longlines as well. An

experiment in the Atlantic using circle hooks to minimize turtle bycatch has had the

unintended consequence of increasing shark catch (A. Bolton, pers. comm.).

Reference to NPOA: Only the IATTC resolution makes reference to parties establishing

a national plan of action for the conservation and management of shark stocks in

accordance with the FAO IPOA17. Even though the IATTC wording is qualified that

15During October, 2006 the EU is considering a Spanish request to increase the amount to 6.5 percent to

account for species and sizes of sharks landed, while a coalition of ENGOs, the UK-based Shark Alliance is

urging a reduction to 2 percent. Part of the argument has to do with the basis of the measurement, i.e.

dressed or whole sharks. According to a press release from the Shark Alliance, the European Parliament

rejected the EU Fisheries Committee's recommendation to increase the percentage, but it is now up to the

European Commission to determine which percentage is used (Shark Alliance 2006).

16 According to observer data held at SPC, this shark is only rarely captured in pelagic longline fisheries in

the WCPO.

17 There are 14 Pacific Island countries that are members of FAO: Cook Islands, Federated States of

Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon

Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu.

24

parties "should establish..." rather than shall establish, the inclusion of such wording

appears to raise the NPOA to a higher standard through its presence in the resolution.

There are two reasons why such a reference may be inappropriate. First, the IPOA is

clearly voluntary (paragraph 10) and, as is stated in the IPOA, is a plan of action. There

may be more appropriate ways for members to set out their goals for the management

and conservation of sharks and the manner in which they can be achieved. Second, the

FAO itself has identified a need to address deficiencies and enhance effectiveness of

the plan. A consultation was held in late 2005 to address these concerns and the subject

is set to be considered at the 2007 meeting of the Committee on Fisheries (FAO 2006b).

Collection of data on shark catches: Both ICCAT and IOTC are specific that they shall

consider appropriate assistance to developing CPCs for the collection of data on their

shark catches. The IATTC provision says it will consider assistance to developing CPCs

for collection of data on shark catches, presumably not just catches of the CPC flag

state.

7 Current Pacific Island Management Approaches to Shark Finning and

Shark Fishing

Attempts to elicit information on management approaches to shark finning by FFA

member countries during the course of this study resulted in a relatively wide range of

attitudes, policies, and legal approaches to the subject of shark fishing but few actual

prohibitions of shark finning.

Only four of the seventeen FFA member countries prohibit shark finning in their tuna

fisheries by either statute or virtue of their membership in one of the three RFMOs that

have passed a recommendation or resolution banning the practice:

· Vanuatu is a member or Contracting Party in all three RFMOs that have passed

binding recommendations or resolutions banning shark finning.

· Cook Islands is a Cooperating non-Party in IATTC, and also makes it is a license

condition of licensed longline vessels that if they catch sharks and wish to keep

the shark fins, the carcass must also be retained (NOAA 2005)

· Palau has stringent prohibitions against possession of any sharks or shark parts

onboard foreign vessels in their EEZ as has been noted above.

· Australia bans shark finning in all its fisheries (Ward, pers. comm.)

7.1 Relevant Information on Shark-related Fishery Management in FFA Member

Countries

The following summarizes additional relevant information on the management of shark

fisheries, shark bycatch, and shark finning in FFA member countries.

Australia: Completed a Shark Assessment Report in 2001 and a National Plan of

Action, Sharks in 2004. In line with the implementation of the Shark-plan,

management measures have been put in place in the longline sector to minimise

25

shark bycatch, prevent indiscriminate finning and to encourage full utilisation of

landed shark catch. Mandatory measures take effect through conditions placed

on relevant fishing permits issued by the Australian Fisheries Management

Authority (P. Ward, pers. comm.).

Cook Islands: No further information at this time

FSM: The law does not allow the targeting of sharks in fishing operations and

fishery administrators accept the use of wire traces or leaders as prima facie

evidence of such targeting.

Fiji: No further information at this time, although there is one report of a ban on

wire traces in the fishery.

Kiribati: No further information at this time

Marshall Islands: A draft NPOA was completed in late 2003 by a consultant

funded by FAO.

Nauru: No further information at this time

New Zealand: Manages most shark and ray species with substantial commercial

catches within the quota management system based on individual transferable

quotas (ITQ). All key shark bycatch species of New Zealand tuna longline

fisheries were introduced into the quota management system on 1 October 2004.

Strict reporting requirements apply. Key highly migratory shark species have

catch limits in place in New Zealand fisheries waters. Catch limits in New

Zealand fisheries waters are set at levels to provide only for bycatch of other

fisheries. New Zealand commissions research to assess shark populations. The

age and growth of key shark bycatch species (blue, mako and porbeagle sharks)

has been contracted. This information will assist in determining sustainable catch

levels. New Zealand is preparing a National Plan of Action for sharks. This plan

will be finalized in 2006. Finning of live sharks in New Zealand fisheries waters is

illegal under New Zealand's Animal Welfare Act. New Zealand recognizes that

landing only the fins of sharks is wasteful. New Zealand considers that the Quota

Management System will provide strong incentives to reduce the practice of only

landing the fins of shark bycatch. Catches are being monitored to determine

whether this is the case. (M. Hooper, pers. comm.).

Niue: No further information at this time.

Palau: Draft NPOA for sharks completed by a consultant in 2004.

Papua New Guinea: A domestic directed shark fishery exists in Papua New

Guinea and has been governed by a shark management plan since 2002 that

allows 9 vessels to be licensed with a Total Allowable Catch (TAC) of 2,000

tonnes (Kumoru 2003).

Samoa: No further information at this time

Solomon Islands: No further information at this time

Tokelau: Foreign fishing vessels licensed to fish in the Tokelau EEZ do so

under New Zealand requirements. No further information at this time

Tonga: Tonga does not encourage targeting of sharks in longline fisheries.

(Sione V. Matoto, pers. comm.)

Tuvalu: No further information at this time.

26

Vanuatu: No further information at this time.

7.2 Pacific Island Fishing Industry Concerns on Shark Finning

The concerns of some in the Pacific Islands tuna longline industry can be described as

both short and long term18. An immediate concern of some vessel operators in the two

FFA countries with the largest domestic fleets (Fiji and Papua New Guinea) regarding

potential banning of shark finning is the loss of revenue from shark fins which has

traditionally gone to either the crew or the vessel owner.

Vessel operators who allow crew to retain income from shark fins likely set pay scales

for their crew on the basis of this additional income, and loss of this source would have

financial implications for those operators. One operator in Fiji estimated that such

income could represent up to 30 percent of crew salaries when significant shark catches

are experienced.

These figures could vary considerably between ports in the Pacific Islands depending on

the circumstances at each port. Ex-vessel prices are often highest where there are

larger volumes produced by more vessels based or calling at a particular port (such as

Suva or Levuka). These ports usually have multiple buyers creating competition that can

drive up prices. There may also be some intermediate processing being done at ports

with larger volumes that change the economics for traders and may allow higher prices

to be paid. Price is also partly determined by onward transportation costs. Those ports

with expensive freight connections to Hong Kong, Singapore and elsewhere in Asia

could offer lower prices than ports with good freight services to those areas19.

Loss of this income to crew would require vessel operators to adjust wages upwards,

something that may not be practical in the current economic environment where fuel and

air freight prices have risen and are not expected to decline.

Vessel operators who use the revenue to offset vessel expenses would also be

squeezed, as overall catch revenue would be reduced. Either way, it is felt by those

queried that the loss of such revenue will exacerbate an already tenuous financial

situation in the industry.

In Palau, some shore-based operators that cater to foreign longliners offloading there

are concerned that the current stringent laws relating to possession of sharks and shark

body parts discourages vessels from offloading or being based in the country. This in

turn has a negative effect on business and exports. These operators suggest that a

relaxation of the current law to allow something like 5 percent of fins equal to sharks

onboard would be a benefit to the economy of Palau.

This sentiment was echoed by two tuna longline vessel operators contacted in PNG and

Fiji. According to these operators, measures to reduce shark catches would be

welcomed by the industry. At present the lack of controls over shark finning can result in

18 Information was obtained by telephone interviews with vessel operators in Fiji and Papua New Guinea, as

well as informal queries made on behalf of this study during an FFA/SPC fishing industry workshop held in

Fiji during September, 2006.

19 An additional factor that may contribute to ex-vessel prices in some ports that are higher than might be

expected given world market conditions is that some traders reportedly use the export of shark fins as a

means to repatriate capital and avoid currency controls. In this situation they may be willing to out-bid

competitors for the purchase of shark fins if the perceive an opportunity for benefits other than from the

shark fins themselves.

27

crews targeting sharks for their own financial benefit, even when the revenue is

supposed to be applied to vessel expenses. They are faced, however, with the problem

that if a ban on finning was to go into effect there would be insufficient space onboard to

store whole sharks and the target catch. This could lead to attempts to hide fins,

resulting in exposure of operators to enforcement penalties.

There is also some concern that in the medium to longer term the strong impetus

provided by success in the banning of shark finning will carry over and reinforce ongoing

efforts at (1) banning the capture of sharks entirely, either as bycatch or in directed

fisheries, leading to (2) banning longlining entirely.

These concerns are not unfounded. Efforts aimed at reducing the capture of sharks

through the use of new technology are already well underway in the developed

countries. The most recent winner of the "Smart Gear" competition sponsored by the

Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) was an idea to place small magnets above baited

hooks that would repel sharks entirely from longlines.

Likewise, efforts to attempt a worldwide moratorium on longlining spearheaded by some

of the more extreme ENGOs20 have been underway for some time and included bringing

the issue before the United Nations during the Informal Consultative Process on the Law

of the Sea, in June, 2005. Dive and eco-tour operators in Palau interviewed in August,

2006 are all in agreement that the efforts resulting in the banning of the possession of

sharks and shark fins by longline vessels in Palau is only a first step towards eliminating

all longlining in the Palau EEZ.

8. Potential Consequences for Pacific Island FFA Member Countries of

Implementing a Shark Finning Ban by the WCPFC

There are two major areas of potential impact to FFA members if a shark finning ban

was to be adopted by the WCPFC. Major impacts would be felt in some countries by (1)

the fishing industry, including those engaged in the shark fin business onshore and (2)

fisheries management authorities with domestic longline fleets in the form of flag state

enforcement requirements.

In order to better understand these impacts, it is useful to briefly review the available

information on the relative importance of shark fins from Pacific Island countries in world

trade, and summarize known commercial activity in FFA member countries

8.1 Summary of Available Information on Shark-related Commercial Activity in

FFA Member Countries

The following summarizes additional relevant information on commercial activity

involving shark fins in those FFA member countries that can be useful in assessing

impacts of implementing measures to ban finning.

FSM: No further information at this time

Fiji: There are currently 63 domestic-based longline vessels licensed in Fiji

which can fish in Fiji's EEZ. An additional 74 longliners are based in Fiji but do

20 An "extreme" ENGO is defined here as one that is known by the author to use or disseminate information

on Pacific Island tuna fisheries selectively and sometimes out of context to further their goals.

28

not operate in the EEZ. Most or all of these vessels participate in shark finning to

some degree, as the market is very active. There are currently five companies

engaged in the processing of shark fins in Fiji, with the number of employees

ranging from 5 to 20. Some of these firms have been engaged in business for a

relatively long time and deal in other commodities such as beche de mer. Most

are Asian or of Asian origin. The sources of fins for these companies are (1)

domestic-based longline vessels, and (2) vessels offloading at the cannery in

Levuka. Only a small amount of the overall supply is thought to be provided by

local artisanal and village-based fisheries. An estimation of the overall annual

value of the shark fin market in Fiji is F$50 million. (A. Turanganivalu, pers.

comm.)

Kiribati: There are reportedly 3 exporters of shark fins in the country, but

volumes and sources of fins, i.e. artisanal or industrial fisheries, are not known.

Marshall Islands: Although there appear to be at least three shark fin exporters

purchasing fins from longliners based in Majuro and purse seiners transshipping

in the harbor, the Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority does not maintain

records on this activity and export values and volumes are unknown.

Nauru: No further information at this time

New Zealand: In FAO statistics, New Zealand ranked 9th in the world in shark

product exporting countries with 4 percent of the world total, about the same as

the U.S.21 (Lack and Sant 2006).

Niue: During the early phases of operation of their shore-based fish processing

plant, it was required for longliners to offload shark trunks from sharks taken in

the fishery. This was apparently done without a firm export market for trunks and

resulted in the search for such markets, assumedly because of a growing

inventory of shark trunks ashore.

Papua New Guinea: Export data indicates an average of about 131 tonnes of

frozen shark fin and 10 tons of dried shark fin were exported during 2001-2005.

Sources of the frozen shark fin is said to be the directed fishery, while dried shark

fin represents bycatch from domestic longliners, and village artisanal production.

In 2005, the declared export value of frozen and dried shark fins combined was

US$1.328 million (L. Kumoru, pers. comm.).

Samoa: The manager of the largest longlining company in Apia claims he does

not get involved with shark fin and leaves it up to the individual skippers and

crews to dispose of them (M. Batty, pers. comm.)

Solomon Islands: Several shark fin exporters are licensed by the Department of

Fisheries and Marine Resources. Honiara is known by some distant water purse

seine crews as a good place to sell fins because of the high prices (S. Retalmai,

pers. comm.).

Tokelau: No further information at this time

Tonga: There are two or three shark fin buyers/exporters in Nuku'alofa, but only

one is consistent. Two companies have conducted export trials with sharks.

(Sione V. Matoto, pers. comm.)

Tuvalu: No further information at this time

21 Taiwan with about 20 percent of the world's total, and Spain with 13 percent were #1 and #2, respectively.

29

Vanuatu: There is one local shark fin buyer in Vanuatu who also deals in beche

de mer. At the village level there is full utilization of sharks. There is one small-

scale artisanal operator based in Santo that targets sharks for fins and teeth,

giving the carcasses to villagers. (W. Naviti, pers. comm.)

8.2 Potential Consequences for the Fishing Industry

The concerns of the Pacific Island fishing industry of a finning ban are cited in section

7.2 as both short and long term. Among PICs, Papua New Guinea with 25 to 40

domestic tuna longliners active at any one time and Fiji with over 60 such vessels have

the largest fleets and would be the countries most affected. Very few (if any) other PICs

would be adversely affected.

It is assumed that the vessels in PNG and Fiji, most of which deliver fresh fish preserved

either in ice or refrigerated seawater (RSW) would not be in a position to retain the vast

majority of captured sharks onboard in order to comply with requirements of finning bans

as adopted by the three RFMOs discussed above. The reasons for this inability or

unwillingness to retain sharks include:

· Limited fish hold space

· Need for special handling22