THE COASTAL OCEANS OF SOUTH-EASTERN

AFRICA

JOHANN R. E. LUTJEHARMS

"The Coastal Oceans of South-Eastern Africa (15,W)" by Johann R. E. Lutjeharms

reprinted by permission of the publisher from THE GLOBAL COASTAL OCEAN: THE

SEA - IDEAS AND OBSERVATIONS ON THE PROGRESS IN THE STUDY OF THE SEAS,

VOLUME 14, PART B, edited by Allan R. Robinson and Kenneth H. Brink, pp. 783-834,

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Copyright © 2006 by the President and

Fellows of Harvard University.

In The Sea, Volume 14B, editors: A. R. Robinson and K. H. Brink,

Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 783- 834

2006

2

Chapter 20. THE COASTAL OCEANS OF SOUTH-EASTERN

AFRICA

JOHANN R. E. LUTJEHARMS

University of Cape Town

Contents

1. Introduction to the region

2. Mozambique Channel

3. Region east of Madagascar

4. Northern Agulhas Current regime

5. Southern Agulhas Current regime

6. Future research directions

Bibliography

1. Introduction to the region

The coastal ocean off south-eastern Africa is characterised by at least one common,

coherent aspect: it forms part of what may be considered to be the greater Agulhas

Current circulation and all its components are largely dominated by this current

system. In other respects it is very diverse (Schumann, 1998). It extends from the

tropics to a region adjacent to the Subantarctic. The shelf regions are very narrow in

some distinct parts and quite wide in others (Fig. 20-001). Certain parts of the shelf

regions have been studied fairly intensively, while for other regions there is no data or

information to speak of. The current extent of knowledge on this coastal ocean region

is therefore, relying on the existing data base, very inhomogeneous.

Knowledge on the bathymetry and geology of the region has not changed

significantly since a previous review of this kind (Schumann, 1998), so will only be

dealt with here where it affects other aspects of the nature of the coastal oceans. The

equatorward border of the system lies at the northern mouth to the Mozambique

Channel (Fig. 20-001). This is a useful and generic choice and not just one brought

about by geographical pragmatism. The major influence of the Indian monsoon

system on the dominant ocean currents lies entirely to the north of this border (e.g.,

Ridderinkhof and de Ruijter, 2003). Numerical model studies (e.g., Maltrud et al.,

1998) suggest a residual monsoonal effect on currents in the Mozambique Channel,

but direct current observations to date do not support this. By contrast, the poleward

border of the region coincides with the termination of the Agulhas Current at the

Agulhas Current Retroflection south-west of the southern tip of Africa. The eastern

border of the coastal oceans of south-eastern Africa has to include the waters to the

east of the island of Madagascar. As is described below, the coastal waters of the east

coast of Madagascar are not a distinctly separate system (Cooke et al., 2004) but in

many ways form a coherent part of the greater Agulhas Current system. Nevertheless,

for organisational purposes the coastal oceans of this system can be separated into

four distinctive parts: the shelf regions in the Mozambique Channel, the shelf regions

east and south of Madagascar, the shelf inshore of the northern Agulhas Current and,

last,

3

Fig. 20-001 Bathymetry of the South West Indian Ocean in km (after Dingle et

al., 1987a and Simpson, 1974) and the major circulation features. Shelf regions

shallower than 1 km are shaded; hatching indicates upwelling. Some major place

and feature names used in the text are given.

inshore of the southern Agulhas Current. As will be seen, making this geographic

distinction between the southern and northern parts of the Agulhas Current is

important since the nature of the waters and the circulation on their respective shelves

are dissimilar (viz. Fig. 20-001). This comes about as a result of the different

behaviour of the edge of the Agulhas Current in these two regions. For an

understanding of the characteristics of waters on the continental shelves it is therefore

necessary briefly to describe the existing knowledge on the offshore ocean currents of

the greater Agulhas Current system.

The Agulhas Current is supplied with water from essentially two different sources:

the South Equatorial Current and recirculation in a South-West Indian Ocean subgyre

(Stramma and Lutjeharms, 1997; Fig. 20-002). The greater part (40 Sv out of a total

65 Sv in the upper 1 000 m) comes from the subgyre. This configuration of the basin-

wide circulation has been thought to be reflected in the behaviour and natural history

of marine animals (Heydorn et al., 1978), for example the migrations of leatherback

sea turtles (Hughes et al., 1998). The manner in which the South Equatorial Current

acts as a source for the Agulhas Current is not entirely clear. It was previously

thought that this current bifurcates on reaching the east coast of Madagascar - forming

the southern and the northern branches of the East Madagascar Current. The northern

branch of this current and the remainder of the South Equatorial Current would then

pass the northern tip of Madagascar and move onwards to the east coast of the African

4

Fig. 20-002 Circulation patterns of the South West Indian Ocean. (After

Stramma and Lutjeharms, 1997.) The thickness of the lines denotes the volume

flux in the upper 1 500 m. Thin lines indicate lines of historical hydrographic

stations on which the portrayal is based. The Agulhas Current along south-

eastern Africa is largely supported by recirculation in a South West Indian

Ocean subgyre.

continent. Here a similar split would occur with some of the water passing northwards

into the Somali Current and the rest southward into the Mozambique Channel as the

Mozambique Current.

These two western boundary currents - the southern limb of the East Madagascar

Current and the Mozambique Current - would then have a confluence somewhere off

South Africa to form the Agulhas Current. This is the classical portrayal of flow in

this ocean region (Michaelis, 1923) still found in many textbooks and most atlases

and is largely based on analyses of ships' drift (e.g., Sætre, 1985; Lutjeharms et al.,

2000b). However, modern observations have shown this depiction to be largely

incorrect. The new findings on these currents are of substantial importance for

understanding the flow patterns on the adjacent continental shelves.

It has been demonstrated that no coherent, unbroken western boundary current

exists in the Mozambique Channel. First adumbrated by using the full set of non-

synoptic hydrographic observations (Sætre and Jorge da Silva, 1984) as well as by

modelling (Biastoch and Krauß, 1999), modern synoptic observations (De Ruijter et

al., 2002) have unequivocally shown that mesoscale eddies are formed at the narrows

of the channel and progress from here southward. No continuous current exists. On

averaging the motions of the drifting eddies (as happens by plotting the means of

many ships' drift observations; e.g., Lutjeharms et al., 2000b) there is the suggestion

of a consistent and continuous boundary current, leading to the classical

misinterpretation.

These Mozambique eddies drift southward along the shelf edge at speeds of

about 5 cm/s and may eventually reach the Agulhas Current (Schouten et al., 2002).

They form the major elements of the circulation in the Mozambique Channel. The

movement in the rest of the channel seems to be sluggish and quite variable, but there

are few observations to support any firm conclusion in this regard, particularly on the

eastern side of the channel. Here there is a dearth of modern hydrographic or current

meter observations (Lutjeharms, 1977). In contrast to classical portrayals, the

Mozambique Channel is therefore now seen as a minor source of water for the

Agulhas Current proper (Fig. 20-002), and only in an intermittent manner. The same

holds for the East Madagascar Current.

5

Instead of being a direct tributary to the Agulhas Current, the southern branch of

the East Madagascar Current has been noted to retroflect south of Madagascar both in

hydrographic data (Lutjeharms et al., 1981a) as well as in satellite remote sensing

(Lutjeharms, 1988). This implies that this current, as in the case of the purported

Mozambique Current, contributes very little to the Agulhas Current, and if so, only

spasmodically. However, the retroflection of the East Madagascar Current has been

shown to be a region that generates both cyclonic as well as anti-cyclonic eddies (De

Ruijter et al., 2003), carrying away some of the shelf waters in the process. Although

these two currents systems East Madagascar Current and Mozambique eddies -

therefore do not form a continuum with the Agulhas Current itself, they do influence

its behaviour indirectly and can therefore be considered to constitute an inherent part

of the greater Agulhas system.

The Agulhas Current proper is fully constituted somewhere near 28° S, along the

east coast of the province of KwaZulu-Natal of South Africa, between Maputo and

Durban (Fig. 20-001). Here the continental shelf is narrow and the course of the

current very stable. This is true for the whole of what might be considered the

northern Agulhas Current (Gründlingh, 1983) extending downstream as far as Port

Elizabeth, at the eastern end of the broad shelf region south of Africa known as the

Agulhas Bank (Fig. 20-001). The coincidence of a narrow shelf and a very stable

juxtapositioned current is not fortuitous; De Ruijter et al. (1999a) have demonstrated

that the continental slope plays an important role in stabilising the trajectory of the

current. The only part of the shelf that does not comply with these stabilising

requirements lies just upstream of Durban, the Natal Bight. At this coastal offset the

shelf is anomalously wide and the continental slope considerably gentler than at other

locations adjacent to the north Agulhas Current. Perturbations on the current path that

occur here will grow, move downstream and have considerable effects on the

subsequent behaviour of the current (Van Leeuwen et al., 2000). This intermittent

meander on the Agulhas Current (Lutjeharms and Roberts, 1988) is called the Natal

Pulse and has a considerable effect on the circulation of the adjoining shelf region.

When the waters in the Agulhas Current reach the Agulhas Bank, the nature of the

current changes dramatically.

From the latitude of Port Elizabeth it is know as the southern Agulhas Current

and, in contrast to the northern Agulhas Current, a range of meanders are formed on

its shoreward side (Lutjeharms et al., 1989a). These meanders cause shear edge

eddies and attendant plumes that move with the current and influence the upper

waters of the shelf in this region. The average trajectory of the current follows the

shelf edge, thus lying farther and farther from the coastline (viz. Fig. 20-001), until

the tip of the Agulhas Bank is passed. In the western lee of the shelf this major current

generates an intense cyclonic eddy (Penven et al., 2001a) that eventually drifts off

into the South Atlantic Ocean. The current itself continues south-westward into the

South Atlantic until it retroflects.

The Agulhas Retroflection is a region exhibiting some of the highest levels of

mesoscale variability in the world ocean (Lutjeharms and van Ballegooyen, 1988;

Garzoli et al., 1996). This is due to the manner in which the retroflection loop

occludes, intermittently forming large Agulhas rings (Lutjeharms and Gordon, 1987)

that then drift off into the South Atlantic (Duncombe Rae, 1991; Duncombe Rae et

al., 1996; Schouten et al., 2000). It has been suggested (Duncombe Rae et al., 1992)

that these rings may interact with the coastal upwelling on South Africa's west coast,

but analyses of the tracks of such rings (e.g., Schouten et al., 2000) indicates that such

6

interaction must be a rare exception. Most rings spend some time in the vicinity of

where they have originally been shed (Boebel et al., 2003), losing a substantial part of

their characteristic heat and salt (Arhan et al., 1999) and having their water masses

exchanged with other rings (Fine et al., 1988) and with Agulhas cyclones (Lutjeharms

et al., 2003b). There is some evidence that Agulhas rings may often be found next to

the western edge of the Agulhas Bank (Lutjeharms and Valentine, 1988) and may

play a role in carrying surface water directly from the Agulhas Current northward past

the western edge of the bank (Lutjeharms and Cooper, 1996).

On moving away from their source region, Agulhas rings tend to move further

away from the African coast (Byrne et al., 1995; Schouten et al., 2000).

Comprehensive reviews of what is currently known about the inter-ocean exchange

that takes place here can be found in Lutjeharms (1996) and in De Ruijter et al.

(1999b). That part of the flow not involved in ring formation, the Agulhas Return

Current (Lutjeharms and Ansorge, 2001), moves water eastward along the Subtropical

Convergence. These deep-sea components of the greater Agulhas system therefore no

longer have a direct influence on the shelf regions. They, as well as the Agulhas

Current proper, may have an indirect effect via their influence on the atmosphere and

on biota.

The Agulhas Current has a marked, visible effect on the overlying atmosphere

through the creation of cumulus clouds (Lutjeharms et al., 1986b), especially along its

southern part and at the Agulhas Retroflection where the heat and moisture loss to the

atmosphere is substantial (Mey et al., 1990). In these regions, under the right

conditions, the thermodynamic considerations adequately account for the formation of

cumulus clouds (Lee-Thorp et al., 1998, 1999). The uptake of moisture in the marine

boundary layer (e.g., Jury and Walker, 1988) can have a marked effect on the

moisture of the adjacent coastal zone and in consequence on the intensities of local

storms and thus on rainfall (Rouault et al., 2002). Increasing rainfall may in turn be

felt in the salinity, water column stratification and colour of the adjacent shelf waters.

Jury et al. (1993) have in fact shown that the distance of the Agulhas Current offshore

has a noticeable effect on the coastal rainfall. Under different climate change

scenarios, the behaviour of the Agulhas Current may change significantly and the

effect on coastal and shelf rainfall may change in concert (Lutjeharms and de Ruijter,

1996).

The Agulhas Current not only has a direct effect on rainfall over the adjacent

coast and shelf, it also has an effect on regional atmospheric circulation patterns

(Reason, 2001) and thus on rainfall over much wider areas. An increase in sea surface

temperature of 2 °C at the Agulhas Retroflection (Crimp et al., 1998) can substantially

affect the atmospheric circulation over the whole southern African subcontinent. An

increase in sea surface temperature over the South Indian Ocean will statistically lead

to an increase in rainfall over regions that form the drainage regions for some of the

main rivers of the South African east coast (Walker, 1990). The effect of increased

runoff on different shelf seas may be very uneven. An investigation of the shelf

waters in the Natal Bight shortly after a major rainfall event (Lutjeharms et al., 2000c)

suggests that it might be relatively insignificant here and restricted to a small area just

offshore of the mouth of the river. Along the Mozambican coast it may, by contrast,

affect the surface salinities of substantial parts of the shelf (Sætre and de Paula e

Silva, 1979).

To summarise: the south-western Indian Ocean may be considered to be that part

of the South Indian Ocean that is not directly influenced by the monsoonally driven

7

ocean currents. The shelf regions of this particular region are largely dominated by

what may be considered to be the greater Agulhas Current system. Along the east

coast of Madagascar and the east coast of South Africa this consists of well-

developed western boundary currents. Along the east coast of Mozambique it consists

of a series of eddies drifting poleward and along the west coast of Madagascar it may

be a sluggish flow with no distinct pattern or temporal behaviour. Too few

observations are available to characterise the latter unambiguously. This is also true

of the behaviour of shelf waters in many other parts of the Mozambique Channel.

2. Mozambique Channel

A proper understanding of the nature of the waters over the shelves of the

Mozambique Channel is constrained by the large degree of ignorance on the water

movement in the adjacent deep sea. As noted above, historically the flow here has

been visualised as consisting of an intense western boundary current along the east

coast of Mozambique. Although this has now been shown to be incorrect (e.g.,

Ridderinkhof et al., 2001), the average drift patterns at the sea surface (e.g., Sætre,

1985) nevertheless indicate a strong movement poleward along the eastern shelf of

Mozambique (Fig. 20-004) whereas elsewhere in the channel the average flow is

small and its direction indistinct. The variability of the flow is very high in the

western side of the channel, but low in the eastern side. This variability is evident in

analyses of ships' drift (Lutjeharms et al., 2000b), altimetric observations (e.g.,

Lutjeharms et al., 2000d) and in modelling of the region (e.g., Biastoch and Krauß,

1999). These results both strong currents at the shelf edge and high variability of

course all agree with the concept of a train of eddies moving poleward through the

channel. Knowledge on the deep sea circulation that may affect the shelves is even

more lacking on the eastern side of the channel.

Ships' drift observations, altimetry and even the few hydrographic observations

give no unambiguous indication of the movement of water here. In general speeds are

low and to the north in the ships' drift observations (Sætre, 1985; Lutjeharms et al.,

2000b) whereas modelling results (e.g., Biastoch et al., 1999) indicate an average

flow to the south. Interpretations from the very few hydrographic data (e.g., Menaché,

1963; Sætre and Jorge da Silva, 1984; Donguy and Piton, 1991) have included a

northward flow as well as a southward flow. The only known direct observations

indicated a weak northward (Martin et al., 1965) and a weak southward flow (Piton

and Poulain, 1974). Satellite observations have indicated the presence of cyclonic

eddies off the shelf edge at the south-western coast of Madagascar that draw coastal

water, rich in chlorophyll-a, seaward (Quartly and Srokosz, 2004). What does stand

out in all appropriate data is that the intensity of current variability on the eastern side

of the channel is considerably lower than on the western side.

2.1 General water mass characteristics in the channel

The temperature-salinity characteristics of the waters in the Mozambique

Channel are shown in Fig. 20-003. This figure is based on relatively old hydrographic

data, but homogeneously covers a greater part of the channel than more modern data.

It demonstrates that the salinities of waters in the upper layers lie in a band between

8

35.00 and 35.40, with a few outliers, mostly as fresher water. These particular outliers

may be due to river runoff. At 18° C there are two different water masses, identifiable

Fig. 20-003 The temperature-salinity and temperature-oxygen characteristics

of the water masses in the Mozambique Channel. (After Lutjeharms, 1991.)

Sigma-t isolines have been added on the T-S scattergram. Water types that are

evident are Equatorial Indian Ocean Water (Eq IOW), Subtropical South Indian

Ocean Water (Subt SIOW), Central Water, Antarctic Intermediate Water

(Antarc IW), North Indian Deep Water (NIDW) and North Atlantic Deep Water

(NADW).

by distinct salinities. They are Equatorial and Subtropical Indian Ocean Water

respectively and are found in different parts of the channel on different occasions. No

durable delimitation for the distribution of either is to be found (Sætre and Jorge da

Silva, 1984), although Equatorial Indian Ocean Water (also called Tropical Surface

Water) is found largely in the northern part of the channel. Since waters to a depth of

900 m are know to upwell onto the Mozambican shelf (e.g., Lutjeharms and Jorge da

Silva, 1988) one can expect to find water types down to the less saline water of the

Central Water (viz. Fig. 20-003) in some coastal regions, but most of the waters on

shallow shelves would come from waters in more superficial layers.

9

Fig. 20-004 Bathymetry of the Mozambique Channel and the continental shelf

off Madagascar in km (after Simpson, 1974) with the major circulatory features.

Shaded areas are shallower than 1 km; hatched areas denote upwelling. Names

of places and features mentioned in the text are given.

2.2 Effects of shelf morphology

The general bottom morphology of the shelves in the Mozambique Channel is shown

in Fig. 20-004. The shelf is narrow on the western side of the narrows of the channel

at about 16° S, but wide on the eastern side. They are fairly narrow on both sides of

the channel at its southern mouth. The rest of the Mozambican shelf is wide, while

that off Madagascar is narrower. Just south of the mouth of the channel there is an

extensive offset in the coastline just off the Mozambican capital of Maputo, the

Delagoa Bight. There is also an offset south of Angoche (Fig. 20-004). The shelves

around the numerous islands, particularly the Comores in the northern mount of the

channel, are narrow. These shapes of the shelf edge have a decided effect on the

coastal water movement.

One of the consequences of the changes in direction of the coastline is in the

formation of coastal lee eddies. An example of such a feature can be seen off the town

of Angoche (Fig. 20-005). Here the flow along the greater part of the shelf edge - and

probably on the shelf as well - is strongly poleward. At the time it was assumed that

this formed part of a continuous Mozambique Current (Nehring, 1984); currently the

10

consensus is that this most probably was part of the edge of an anti-cyclonic eddy

drifting southward (e.g., De Ruijter et al., 2002). Notwithstanding the ignorance on its

Fig. 20-005 Lee eddy at Angoche along the Mozambican coast (viz. Fig. 20-

004). The dynamic topography of the sea surface relative to the 600 dbar level is

given in dynamic centimetre, based on a cruise undertaken in 1980. Dots

represent station positions. The continental margin shallower than 1 km is

shaded. (After Nehring et al., 1987.)

source, the important thing to note is the fact that there was a strong current poleward

on this occasion, even though it might have been intermittent. This current overshot

the offset in the coast at about 16° S, forming a distinct lee eddy to the south (Fig. 20-

005). This eddy had a diameter of about 100 km and deeper water was upwelled in its

core (Schemainda and Hagen, 1983). This is shown by an enhanced nutrient content

of more than 12 mol/ nitrate-nitrogen at 75 m depth compared to 2-4 mol/ in the

offshore current at the same depth. A resultant peak in chlorophyll-a concentration

was also observed in this lee eddy (Nehring et al., 1987). Although no hydrographic

stations were carried out on the shelf itself, the implication clearly is that the motion

on the adjacent shelf would be equatorward.

The shelf configuration at this presumed lee-eddy is similar to that of the St Lucia

and the Port Alfred upwelling cells (Lutjeharms et al., 1989b; Lutjeharms et al.,

2000a; Figs 20-001 and 20-016). At all three of these locations a strong current along

the shelf edge moves past an offset in the coastline, from a narrow shelf and then past

a wider shelf. According to the theory put forward by Gill and Schumann (1979), this

should lead to upwelling inshore of the strong current. In the former two cases it does,

therefore perhaps also off Angoche at about 16° S in the Mozambique Channel. In his

analysis of seasonal sea surface temperatures and the depths of isotherms along this

coastline, Jorge da Silva (1984a) has shown the prevalence of upwelling at this spot,

but only for certain periods of the year. His database for such seasonal analysis was

not very large, so that this result can only be considered tentative. If the hypothesis is

correct and this upwelling is driven by poleward currents as part of passing eddies, it

would be sporadic and not a continuous feature. Nevertheless, this spot represents the

11

highest observed chlorophyll-a values along this coastline (Nehring et al., 1987) and

may therefore have a decided influence on the ecosystem of this whole shelf region.

If the offshore eddies that form at the narrows (De Ruijter et al., 2002;

Ridderinkhof and de Ruijter, 2003; Fig. 20-004) consistently move along the shelf

edge it is likely that the waters on the adjacent shelf would experience alternating

poleward and equatorward setting currents. This situation is also found on the shelf

adjacent to the northern Agulhas Current where the shelf waters move largely in

harmony with the current, but on the intermittent passing of a Natal Pulse, reverse and

set strongly against the direction of the Agulhas Current (Lutjeharms and Connell,

1989). Quartly and Srokosz (2004) have used satellite observations of ocean colour to

demonstrate that passing Mozambique eddies extract water from the neighbouring

Mozambican shelf and inject it into the mid-channel region. In this way the exchange

of waters between the shelf and the deeper part of the channel will consist of rather

frequent episodes, driven from afar. They (Quartly and Srokosz, 2004) have also

shown that the passage of eddies past the Delagoa Bight appears to affect the

circulation there.

Fig. 20-006 The Delagoa Bight eddy off the city of Maputo in southern

Mozambique (viz. Fig. 20-04). Isotherms at 200 m depth show the cold water

upwelled in the centre of the eddy, based on a cruise undertaken in 1982. (After

Lutjeharms and Jorge da Silva, 1988.) The broken line shows the intersection of

the 200 m isobath with the shelf edge; the shelf itself is shaded.

The Delagoa Bight is a large offset in the coastline at the latitude of Maputo (see

Fig. 20-004). The flow past here, either as the start of the Agulhas Current or as the

landward end of passing, anti-cyclonic Mozambique eddies, is poleward. This passing

water generates a cyclonic flow in the bight (Lutjeharms and Jorge da Silva, 1988)

and the resultant Delagoa Bight eddy dominates the flow at the shelf here throughout

most of the year (Fig. 20-006). Over a period of 23 years it has been observed 11

times in the hydrographic results of research cruises. It has been hypothesised that this

12

recurrent eddy has largely determined the distribution of the sediment base of the

Delagoa Bight (Martin, 1981). There is evidence (Gründlingh, 1992a) that these

eddies may on occasion escape from the bight and drift into the deep ocean. On this

part of the Mozambican shelf the water movement will most probably be totally

dominated by this lee-eddy. If the same effects are found here as in lee-eddies in the

other offsets in this coastline (e.g., Nehring et al., 1987), it can be assumed that there

is considerable vertical movement of water in the lee eddy (Schemainda and Hagen,

1983). Water masses in this eddy have temperature-salinity characteristics implying

substantial upwelling in the core of the eddy from depths of at least 900 m. Hence

there should be nutrient enrichment of the surface layers and thus increases in the

chlorophyll-a content. To date this has not been observed, except intermittently at the

north-eastern point of the Delagoa Bight (Quartly and Srokosz, 2004). This sporadic

increase in primary productivity may be the result of current-induced upwelling as

predicted by Gill and Schumann (1979). If driven by passing eddies, such intermittent

upwelling would be expected.

The shelf morphology of the eastern part of the Mozambique Channel is different

to that of the western part (Fig. 20-004). For the most part the shelf is narrow except

at the narrowest part of the channel at about 17° S where the eastern shelf is

widest. As mentioned before, the flow along this eastern shelf edge is quiescent

compared to the western side of the channel (Sætre, 1985; Lutjeharms et al., 2000b)

with low speeds and low eddy kinetic energy. The average current direction seems to

be equatorward. Nevertheless, there are tentative indications from the distribution of

chlorophyll-a (Quartly and Srokosz, 2004), as observed from satellite, that cyclonic

eddies form along the southern tip of Madagascar and drift into the channel. They

seem to draw water off the shelf and inject it into the waters of the central channel.

In summary, the shelf edges of the western part of the Mozambique Channel

seem to be influenced mainly by passing Mozambique eddies that have their origin in

the narrows of the channel and by secondary effects due to these eddies, namely

upwelling at coastal offsets, the generation of lee eddies at shelf offsets and the

extraction of shelf waters to mid-channel. It is possible that parts of the eastern shelf

of the Mozambique Channel are also influenced by eddies, but the data at hand are

inadequate to show this unambiguously. It is evident that such eddies would be

considerably more infrequent than and not as intense as those that affect the western

shelf of the channel. Besides the direct influence of the currents at the shelf edge, the

waters over the shallower parts of the shelf may be substantially influenced by the

reigning winds.

2.3 Effect of winds and tides

The meteorological conditions for the Mozambique Channel have been summarised

by van Heerden and Taljaard (1998). In austral summer the mean wind direction is

uniformly from a south-easterly direction and weak. In winter the average wind

direction differs for the southern and the northern part of the channel. The southern

part experiences south-easterly winds; the northern part north-westerlies. The

northern part thus may be considered to form part of the monsoonal wind system of

the Indian Ocean up to 15° S (Sætre and Jorge da Silva, 1982) whereas the southern

part does not. The border between these two systems is the Inter Tropical

Convergence Zone. Donguy and Piton (1991) have attempted to relate the currents in

the channel to the monsoonal winds, but with only a few cruises and short sea level

13

records at their disposal a conclusion of monsoonal seasonality in the currents is

probably premature. As mentioned above, the large scale current systems show no

evidence of monsoonal influence.

The winds over the shelf regions agree in part with the current direction

hypothesised by Sætre and Jorge da Silva (1984). Except for the most southern part of

the western shelf the Delagoa Bight the winds along this coastline all have a

strong equatorward component year round. Sætre and Jorge da Silva (1984) have

therefore concluded that the shelf currents here also are in that direction. These

inferred current directions are in contrast to ships' drift observations (Sætre, 1985;

Lutjeharms et al., 2000b) that show consistent movement poleward over the western

shelf region. The winds over the eastern shelf are also largely northward, but vary

with season.

During summer the shelf waters of the Mozambique Channel may also be affected

by passing tropical cyclones that, as a rule, move poleward through the channel (Van

Heerden and Taljaard, 1998). Some, however, make landfall somewhere along the

coast of Mozambique. The effect of passing cyclones on the water movement over the

shelves is dramatic. In situ current observations have shown (H. Ridderinkhof,

personal communication) a reversal of current direction to a depth of at least 200 m at

the passing of a severe cyclone.

Tides are an important component of water motion in the Mozambique Channel,

especially when compared to other parts of the South-West Indian Ocean where tidal

ranges are small. There is a gradual increase in tidal range from less than 2 m to the

north and to the south of the channel to more than 5 m in its central part. This is the

product of a double standing wave system, driven from either end, which develops in

the channel (Pugh, 1987). Low lying coastal regions and estuaries, particularly on the

Mozambican side, contain extensive areas of salt marshes and mangrove swamps as a

result of the tidal motion (G. B. Brundrit, personal communication). Over the wide,

shallow parts of the Sofala Bank (viz. Fig. 20-007) strong tidal currents lead to the

continuous movement of sand banks and other mobile sedimentary seabed features.

In summary, tidal currents are important in the shallow parts of the shelves, but the

usually weak winds have a limited affect on the main water movement over the

shelves of the Mozambique Channel, with the exception of passing cyclones whose

influence might be short lived.

Apart from the wind regimes, in a region of high rainfall (Van Heerden and

Taljaard, 1998) the influence of river runoff on the shelf waters may be important.

2.4 Effect of river runoff

The runoff from the Mozambican land mass varies seasonally, but there also are

considerable interannual differences (Jorge da Silva, 1984c). The total runoff from the

Zambezi River (viz. Fig. 20-004, 20-007), for example, was 168.9 km3 for 1977-78;

whereas for 1982-83 it was a mere 50.3 km3. Intermittent tropical cyclones bring

event-scale rainfall episodes that may totally dominate the annual rainfall distribution.

This naturally also holds for the Madagascar land mass, but runoff records for that

country are difficult to obtain. One of the few coastal regions for which accurate

observations of the effect of the river runoff on the shelf waters have been made on a

number of occasions (Jorge da Silva, 1984c; 1984b) is along the Sofala Bank. It lies

between 16° and 21° S on the western shelf of the channel (Fig. 20-004).

14

The salinity of surface waters close to the Zambezi River mouth on the Sofala

Bank may drop as low as 20.00 (Sætre and de Paula e Silva, 1979) at a time when

water at the shelf edge may be 35.4 (viz. Fig. 20-007). This river water may be

severely discoloured, giving a Secchi disc depth of less than 2 m (Jorge da Silva,

1984b). The

Fig. 20-007 Surface salinities on the Sofala Bank - the wide, shallow shelf off

central Mozambique - based on a cruise of 1982. (After Jorge da Silva, 1984c.)

For general location see Fig. 20-004. Dots show station positions. Locations of

station sections in the bottom panels are shown by roman numerals in the upper

panel. The shelf shallower than 50 m is shaded. Fresher water (< 35.0) extended

to a depth of 15 m directly off the Zambezi River mouth; to 30 m off the Luala

15

River mouth. Note the high salinity values south of the city of Beira, due to

marsh runoff.

plume of muddy water can be quite extensive (Sidorn et al., 2001) and has been

thought to play a major role in the natural history of local biota, such as shrimp. The

fresher water may extend over the shelf to a distance of 50 km offshore. It may be

confined to the top 15 m of the water column, or it may extend to the full depth of the

shelf (Fig. 20-007), presumably dependent on the density differences between the

river and shelf waters as well as the concurrent wind action. Plumes of fresh river

water have been observed to extend both equatorward as well as poleward from most

rivers here. No clear pattern of movement is therefore immediately evident. Sætre and

de Paula e Silva (1979) have shown that the greater part of the Sofala Bank is affected

by fresher surface water.

The chlorophyll-a distribution as well as the primary productivity on the Sofala

Bank seems to be largely controlled by the effluent from rivers. These carry loads of

nutrients (Jorge da Silva, 1984c) that, as mentioned above, may penetrate half-way

across the shelf. The chlorophyll-a distributions exhibit very analogous patterns. That

these distributions occur with a high frequency can be seen by the organic matter

content of the surface sediments on this part of the shelf. It is highest directly off the

Zambezi River mouth and in a narrow strip adjacent to the coast to either side of this

river mouth. Some small pelagic fish seem to concentrate in these waters (Jorge da

Silva, 1984c). Otherwise pelagic fish on the Sofala Bank seem chiefly to frequent

strips parallel to the coast, most extending along the whole coastline (Brinca et al.,

1981).

One may quite reasonably expect the observed effects of fresh water runoff on the

Sofala Bank to hold for the rest of the shelf regions of the Mozambique Channel as

well, where there are fewer measurements of this kind. The salinity of shelf waters

along most of Mozambique varies seasonally with the river outflow, with the lowest

salinities found in February (Sætre and de Paula e Silva, 1979). Apart from the

expected seasonality, results for the Sofala Bank show great inter-annual variability

and one could assume that this holds for all the other Mozambican shelf regions as

well. The freshening of the shelf waters off Mozambique by river run-off seems

ubiquitous.

There is at least one clear exception. At the southern extremity of the Sofala Bank,

between 20° to 21° 30' S (viz. Fig. 20-007), there is a large expanse of coastline that is

subject to inundation by seawater. The subsequent runoff from this region can be

extremely salty. Salinity values in excess of 36 are not uncommon (e.g., Jorge da

Silva, 1984c). During September of 1982 surface values of 37.2 were observed near

the coast (Brinca et al., 1983). The influence of this saline water has been observed a

distance of 100 km offshore and throughout the shallow water column of 50 m.

2.5 Characteristics of the western shelf

To recapitulate, the water mass characteristics of the shelf waters on the western shelf

of the Mozambique Channel have been presented by Jorge da Silva et al. (1981),

Jorge da Silva (1984a), Lutjeharms and Jorge da Silva (1988) and Sætre and Jorge da

Silva (1982). Except for regions and times where river run-off plays a major role, the

water masses over the shelf are identical to those offshore (viz. Fig. 20-003) at the

same depths. This means that the subsurface salinity maximum of Subtropical Surface

16

Water (at depths of 150 300 m) is much more pronounced in the southern part of the

channel than farther north. In the Delagoa Bight eddy, at the southernmost extremity

of the shelf (Lutjeharms and Jorge da Silva, 1988), there is hardly any evidence of

Tropical Surface Water left. The exchange of water masses between the shelf and the

deep ocean seems to vary considerably. The passage of Mozambique eddies may play

a key role here. At parts of the western shelf where the shelf is very narrow (viz. Fig.

20-004) and the current at the shelf edge strong, such as at the narrows of the channel

(Angoche; Sætre, 1985) and just north of the Delagoa Bight (Inhambane; viz. Fig. 20-

004; Lutjeharms et al., 2000b), one may expect that the shelf edge currents may have

a more decided effect, whereas along the Sofala Bank where the shelf is widest (Fig.

20-004), this effect would be substantially less.

Sætre and Jorge da Silva (1982; 1984) have carried out the most detailed analyses

of water masses on this shelf to date. They have claimed that the circulation patterns

of the shelf waters can be visualised by the temperature distribution at 150 m depth.

This leads to a different pattern for the hydrographic results of each research cruise

for the region. A set of cyclonic eddies of various shapes and sizes are evident. Based

on these data one may therefore safely assume that the waters and the circulation on

this shelf region are very variable. What effect does this have on the ecosystem of this

shelf region?

Surveys of organisms and in particular of fish resources have been made on the

western shelf region of the Mozambique Channel (Nehring, 1984; Nehring et al.,

1987; Sætre and de Paula e Silva, 1979; Jorge da Silva, 1984a), but particularly on the

Sofala Bank (Brinca et al., 1981; Jorge da Silva, 1984c). The values of column

chlorophyll-a concentration are relatively low over most of the outer parts of the

shelf, somewhat higher at the shelf edge (Sætre and de Paula e Silva, 1979). Over

inner parts it can rise to 98 mg/m2 (Nehring et al., 1987). The exception, mentioned

above, are the observations in the upwelling cell off Angoche where values of 600

mg/m2 have been observed. The distribution of zooplankton biomass in the upper 30

m of the water column shows a similar general distribution with low values of 20-40

mg/m3 over most outer parts of the shelf with higher values, up to 160 mg/m3 at inner

stations. The exception is for the region directly poleward of the Angoche upwelling

cell where observations of 320 mg/m3 have been made. No evidence for such major

increases in either phytoplankton or zooplankton have to date been found in the

Delagoa Bight eddy. Even though Nehring et al. (1987) have shown that the primary

productivity at inshore stations on the shelf was double that of stations farther

offshore, there were considerable differences between stations close to each other on

the shelf. Large degrees of spatial and temporal variability can therefore be assumed.

An analysis of the seasonal distribution of the depth of the 20° and the 23° C

isotherms has shown that large parts of the outer shelf would in principle be suitable

for yellowfin tuna fisheries, whereas the skipjack tuna are most likely to be found off

Angoche and Maputo, i.e. at the sites of upwelling induced by lee eddies (Fig. 20-

008). The distribution of fish; demersal, small pelagic, larger pelagic, mesopelagic as

well as that of crustaceans has been summarised by Sætre and de Paula e Silva

(1979). In most cases where more than one survey cruise was carried out there was a

considerable difference between the cruise observations and this was usually

considered to be due to seasonality in the distribution of organisms. It may have been

due to irregular temporal changes of shorter duration.

In short, the circulation on the Mozambican shelf is very variable in both space and

time and may be influenced by offshore currents only where the shelf is narrow. Run-

17

off from land plays a key role, but exhibits both seasonal and inter-annual variations.

The biogeography exhibits the same variability. Although the interpretation of the

circulation patterns as well as the biogeography of this western shelf of the

Mozambique Channel is constrained by limited data, this is even more the case for the

eastern shelf.

Fig. 20-008 Tuna vulnerability to catching by surface gear on the Mozambican

shelf, superimposed on average sea surface temperatures during the period

January to March. (After Jorge da Silva, 1984a.) The 50 m isobath is shown.

Note the increased concentration in the lee eddies off Angoche and in the

Delagoa Bight off Maputo.

2.6 Characteristics of the eastern shelf

18

The eastern shelf of the Mozambique Channel can using information currently

available - be divided into three specific regions: the very south where the shelf is

more or less zonal, the very north, where the shelf forms part of the Comoro Basin

(viz. Fig. 20-004) and, third, the meridional shelf in between.

The Comoro Basin lies directly south of the South Equatorial Current (Piton and

Poulain, 1974). Between it and the narrows of the channel an anti-cyclonic gyre is

formed that seems relatively stable (Donguy and Piton, 1991). The surface currents of

which the gyre consists are not strong (Sætre, 1985) except near the African coast

where mean speeds in excess of 0.5 m/s are to be found (Lutjeharms et al., 2000b).

The variability on the African side is high. The currents over the eastern shelf in the

Comoro Basin are weak but in general in an equatorward direction. This rather

inadequate portrayal is nonetheless supported by direct measurements (Piton and

Poulain, 1974; Martin et al., 1965) as well as by a variety of models (e.g., Biastoch

and Krauß, 1999; Asplin et al., 2004; Sætre, 1985).

The water types on the shelf are dominated here by Tropical Surface Water with a

salinity range from 34.3 to 35.2 (Donguy and Piton, 1969). There is no evidence to

date that Subtropical Surface Water with greater salinity is found on the shelf,

although in principle it is entirely possible since this water mass is found at about 200

m depth in the region. Surface temperatures exceed 26° C throughout the year, except

in the months of August and September. Highest temperatures (> 29°) are found in

April; lowest (25° to 26° C) in August. Surface salinities are lowest (34.4) in March;

highest in the period September to November (>35.10). Recent observations on this

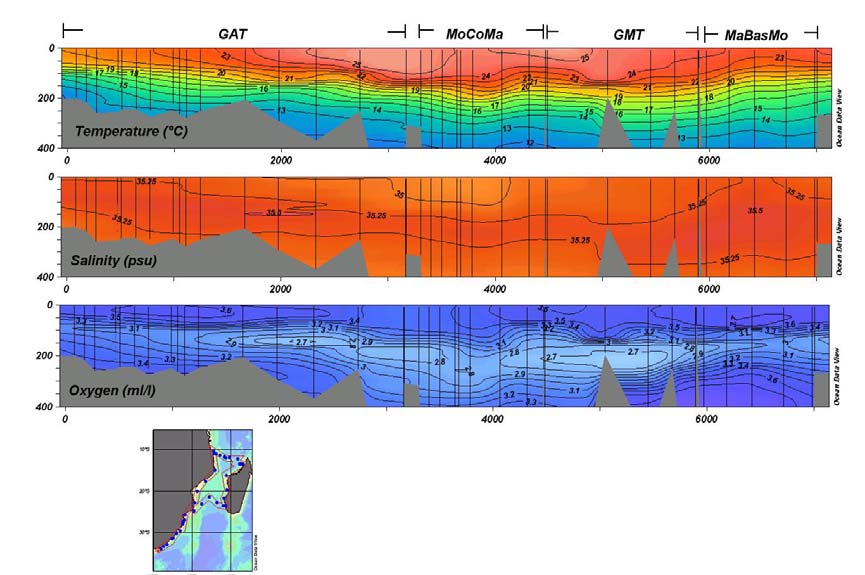

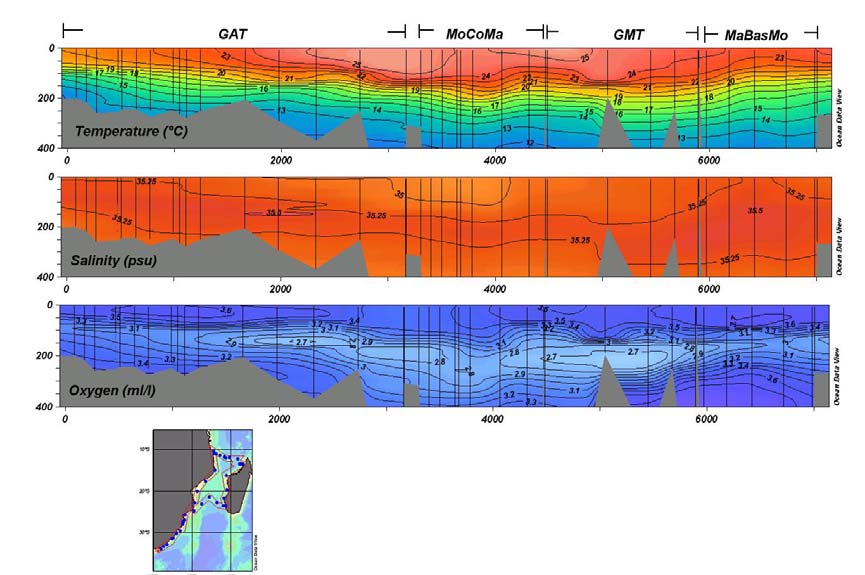

Fig. 20-009 Hydrographic characteristics of shelf waters along the east coast

of South Africa and the continental shelves in the Mozambique Channel. (With

special permission of M. Roberts.) GAT is the section from Port Elizabeth in the

south along the east coast of South Africa and of Mozambique; MoCoMa

represents the zonal section from the coast of Mozambique to the west coast of

Madagascar via the Comores; GMT a poleward section along the west coast of

19

Madagascar and MaBasMo a zigzag section from the southern point of

Madagascar to the island of Bassas da India and on to Maputo on the east coast

of Mozambique.

shelf region (Roberts, personal communication) shows that the water column consists

of a warm mixed layer to a depth of about 80 m with the seasonal thermocline

extending to 250 m. Salinities in the centre of the Comoro Gyre are slightly elevated

above those found on the adjacent shelves. An oxygen minimum lies at 200 300 m

depth and is less strongly developed in the centre of the gyre. The hydrography of the

middle part of the western shelf of Madagascar is not much different.

Here, according to the only observations to be found (Roberts, personal

communication) the warm mixed layer extends to 150 m, with a uniform salinity

between 35 and 35.25 (Fig. 20-009). Particularly noteworthy is the oxygen minimum

layer found between 150 and 250 m that is strongly developed here, more so than

anywhere else on the shelves of the region. How representative these observations are

remains unknown. The little that is known about the currents along the shelf edge

(e.g., Sætre, 1985; Lutjeharms et al., 2000b) here, suggest that they are very weak and

will most probably have very little influence on the movement of the waters on the

shelf itself. As mentioned before, satellite imagery, particularly of ocean colour

(Quartly and Srokosz, 2004), shows that cyclonic eddies along this coastline may on

occasion draw off substantial amounts of shelf water and with it chlorophyll-a into

the deeper parts of the channel. The origin of these eddies, between 200 to 300 km in

diameter, is uncertain. De Ruijter et al. (2003) have shown that cyclones can be

formed at the termination of the southern East Madagascar Current and these could

Fig. 20-010 The temperature/salinity (left panel) and the temperature/dissolved

oxygen characteristics for the shelf waters south of Madagascar. (After

20

Anonymous, 1983.) The line of stations on which this was based was taken to the

south-west of Andriamanao (viz. Fig. 20-04).

conceivably drift into the Mozambique Channel along the shelf edge. Although a

number of hydrographic interpretations (e.g., Sætre and Jorge da Silva, 1984; Donguy

and Piton, 1991) imply a southward setting current along this shelf, direct

measurements (Martin et al., 1965) and ships' drift observations (Lutjeharms et al.,

2000b) indicate otherwise. Cyclonic eddies could therefore be advected equatorward

along this coast.

The third and last component of the eastern shelf of Madagascar is the southern

part. The movement of the shelf waters here may be more dynamic, since it could

conceivably be affected by the southern limb of the East Madagascar Current (viz.

Fig. 20-004). This would most likely be true largely for the eastern part of this shelf

region (Lutjeharms et al., 2000b). Hydrographic observations on the shelf show the

normal temperature/salinity characteristics to be expected (Fig. 20-010). Surface

temperatures (in June) were 24 °C and surface salinities 35.3. (The higher

temperatures shown in the scatter diagram of Fig. 20-010 represent temperatures

farther offshore.) Both Tropical and Subtropical Surface Waters are evident in the

temperature/salinity values. The Tropical Surface Water extended from the surface to

about 100 m depth. The Subtropical Surface Water below that extended to about 250

m. A well-developed subsurface oxygen minimum was found at a depth of 80 to 200

m.

The surface salinities and temperatures all suggest an upwelling regime on this

southern shelf. During the first extensive cruise over this shelf (June 1983;

Anonymous, 1983) the temperatures at the coast were 2 °C lower than further

offshore. The salinities were up to 35.6, indicating upwelled Subtropical Surface

Water (see Fig. 20-010). Ocean colour also shows signs of enhanced chlorophyll-a

values along this coastal segment (Quartly and Srokosz, 2004) and that these may be

drawn off the shelf in plumes. The presumed upwelling is concentrated in an

upwelling cell on the south-eastern corner of Madagascar (Lutjeharms and Machu,

2000; DiMarco et al., 2000) where enhanced concentrations of chlorophyll-a and

lower temperatures are found most frequently. The question remains if these remotely

sensed suggestions of upwelling may not be due to runoff from land.

Hydrographic evidence specifically collected to ascertain the origin of these

elevated values of chlorophyll-a (Machu et al., 2002) has recently shown

unequivocally that there is indeed upwelling at this location. The upwelling does not

seem to be strictly related to the wind patterns and it has therefore been hypothesised

(Lutjeharms and Machu, 2000) that the driving force for the upwelling is the

juxtapositioned East Madagascar Current. This would be comparable to the upwelling

at the eastern extremity of the Agulhas Bank (Lutjeharms et al., 2000a; viz. Fig. 20-

016) and at the northern extremity of the Natal Bight (Lutjeharms et al., 1989b; viz.

Fig. 20-011). However, there is some evidence (Quartly and Srokosz, personal

communication) that the chlorophyll-a concentration at this location has a distinct

seasonal pattern with the highest concentrations found in the austral winter months of

July and August, the lowest in December. Major winds at this location are from the

east in winter, from the north-east in summer (Sætre, 1985) suggesting winds more

favourable for upwelling along the full south coast of Madagascar in winter, at the

south-eastern corner in summer. The importance of the wind compared to the current

in driving this upwelling therefore remains unresolved.

21

The biological implications of this upwelling are intriguing, but to date not

properly quantified. Apart from the remotely sensed chlorophyll-a, surveys of fish

stocks (Anonymous, 1983) have shown slightly higher concentrations of demersal

fish on the southern shelf than off the adjacent, eastern shelf. Mackerel numbers were

higher on the southern shelf, but scad lower. In general fish were found with such a

very scattered distribution on this shelf that no firm conclusions can be reached on

their biogeography.

In summary, the waters over the shelves of western Madagascar seem fairly

unusual, based on the current - very limited - data. Water masses are those found

offshore, except for an intensification of the subsurface oxygen minimum, and the

currents are most probably weak and variable. The wider, southern shelf exhibits

characteristics of upwelling, but this does not seem to have a marked effect on higher

trophic levels.

An outline of the characteristics of the shelf waters of the Mozambique Channel as

a whole is, as can be seen from the above descriptions, largely a function of the

amount of available data and their quality. The broad Mozambican shelf is

characterised by substantial terrestrial influence from runoff both from rivers and salt

marshes. Lee eddies at Angoche and in the Delagoa Bight may play an important, but

local role. The effect of Mozambique eddies intermittently passing by the shelf edge

is not known. Water masses over the northern shelves are predominantly Tropical

Surface Water, those to the south Subtropical Surface Water. This seems true for the

western as well as the eastern shelves of the Mozambique Channel. About the latter

very little is known, except that it is relatively broad.

The shelf to the east of Madagascar is by contrast much narrower and the offshore

circulation totally different.

3. Region east of Madagascar

Not only is the shelf narrow here, but the continental slope is precipitous (viz. Fig. 20-

004). Along the shelf flows a small, but intense western boundary current, the East

Madagascar Current (e.g., Lutjeharms et al., 1981a). Swallow et al. (1988) have

observed a speed in the southern limb of this current of 0.66 m/s, at a latitude of 23

°S, about 50 km from the coast, with a standard deviation of only 12 cm/s. The speeds

in the northern branch of this current (Schott et al., 1988) are not much different. The

separation point between the northern part, flowing equatorward, and the southern

part, flowing poleward, is estimated to lie between 17 and 18 °S (e.g., Lutjeharms et

al., 2000b; viz. Fig. 20-004). This may vary with season as the wind patterns shift

northward along this coastline in the austral winter (Van Heerden and Taljaard, 1998).

No direct observations have been made to date, but one may assume that the waters

over the shelf move in concert with the strong offshore currents.

As can be expected, the temperature/salinity relationships of the waters on this part

of the shelf are indistinguishable (Anonymous, 1983) from those found on the shelf

south of Madagascar (Fig. 20-010).

Little is known about the biological productivity of the region. Fish distributions

are scattered with a decrease in pelagic as well as demersal fish as one moves

equatorward. Catches of sharks and rays increase on going northward along this coast

(Anonymous, 1983).

22

In summary, all that is known with a certain degree of certainty about the shelf

seas east and south of Madagascar is the presence of the East Madagascar Current at

the shelf edge and the likelihood of persistent upwelling south-east of the island. The

interaction between these or the influence of the current on the shelf circulation

remains unknown due to an extreme paucity of observations.

Compared to the lack of data and knowledge about this particular part of the shelf

seas of the South-West Indian Ocean, the region inshore of the northern Agulhas

Current is very much better studied and understood.

4. Northern Agulhas regime

The northern Agulhas Current is defined as that part of the current extending from the

southern mouth of the Mozambique Channel downstream to the eastern edge of the

Agulhas Bank (viz. Fig. 20-001). This component of the current flows past a shelf that

may be considered to consist of two categories. For the greater part the shelf is narrow

and the continental slope has a steep gradient. The only exception is a part of the shelf

along the province of KwaZulu-Natal known as the Natal Bight. Here the shelf is

considerably wider and the slope much broader and with a gentler gradient (Fig. 20-

011). As will be seen below, this shelf morphology has some remarkable effects on

the offshore currents.

23

Fig. 20-011 The bathymetry of the continental shelf along the northern Agulhas

Current. (After Simpson, 1974.) The continental shelf area is shaded. The 200 m

isobath is shown as a broken line. Hatched areas denote upwelling. Place names

and circulatory features are mentioned in the text.

The core of the northern Agulhas Current follows the shelf edge very closely

almost all of the time (Tripp, 1967) meandering less than 15 km to either side

(Gründlingh, 1983). For a western boundary current this is quite unusual, but it has

important consequences for the circulation on the adjacent shelf. As can be expected,

in its very surface layers the behaviour of the current is not as stable (Pearce, 1977a)

with changes in speed occurring from day to day and the penetration of surface water

of the current onto the shelf taking place at irregular intervals. In some cases short-

term current reversals at the edge of the current have been observed (Gründlingh,

1974; Schumann, 1981; Pearce et al., 1978), possibly due to shear edge eddies or to

the effect of the wind. Surface speeds of the inshore edge of the current may exceed

1.5 m/s, salinities may lie between 35.00 and 35.50 and temperatures in summer may

exceed 28. In winter these sea surface temperatures drop to less than 21 °C (Pearce,

1978). Shallow water near the shelf edge is usually Tropical Surface Water. The

characteristic salinity maximum of Subtropical Surface Water is found at a depth of

150 to 250 m at least 60 km offshore (Pearce, 1977a) although this distance may vary

on a near-daily basis. One would therefore expect the waters over the adjacent shelves

to consist largely of modified Tropical Surface Water, but as it turns out, this is not

the case.

This established current disposition is not entirely stable, as mentioned above.

During about 15% of the time and at irregular intervals the current moves offshore

in a sudden, single meander (Gründlingh, 1979). This Natal Pulse (Lutjeharms and

Roberts, 1988) moves downstream with the current at a rate of about 20 km/day.

Features of this kind have also been observed north of the Natal Bight (Gründlingh

and Pearce, 1984; Gründlingh, 1992a), however, all information currently available

suggests that it is only meanders that originate at the Natal Bight that consistently

progress downstream with the current. Theoretical studies (De Ruijter et al., 1999a)

have shown that it is the weak gradient of the shelf at the Natal Bight that will allow

baroclinic instability in the Agulhas Current to occur here and to grow once the core

of the current has been detached from the sharp slope gradient. The trigger for this

meander has been thought to be the adsorption of offshore eddies, the tell-tale signs of

which have been seen in many satellite images in the thermal infrared (e.g.,

Gründlingh, 1986; Lutjeharms and Roberts, 1988). This has recently been proven to

be the case (Schouten et al., 2002). It is interesting to note that some marine animals

such as leatherback sea turtles carefully use all these circulation features to move

about in the ocean (Hughes et al., 1998; Luschi et al., 2003). The question remains

what, if any, effects these unusual meanders have on the shelf waters. This will be

discussed in a section to follow. It is necessary first to describe the wind regimes over

this shelf region.

4.1 Winds along the shelf off south-eastern Africa

Tropical cyclones hardly ever reach this coastline, in contrast to that of Madagascar

and Mozambique (Jury and Pathack, 1991). On the infrequent occasions when they do

arrive at the coast (e.g., Poolman and Terblanche, 1984), one would expect the

24

shallow waters of the shelves over which they move to be thoroughly mixed.

Otherwise the shallow waters, as measured by moored current meters (upper ~20 m),

follow the reigning winds closely (Pearce et al., 1978).

Coastal winds for the region have been analysed in detail by Schumann (1989). He

has shown that the main wind axis is parallel to the coast. At Durban the wind is 5

times more likely to blow along the shelf than across it, whereas at East London (viz.

Fig. 20-011) it is three times more likely. Average wind speeds are about 2.5 m/s at

Durban; 3.2 m/s at East London (for 1984). The average wind speeds along the coast

and across it were not very different. The north-easterly wind and the south-westerly

winds both occur about 50% of the time (Schumann and Martin, 1991), with both

showing seasonality in wind speed, the north-easterly winds having slightly greater

seasonality. During summer the alongshore component of the wind is considerably

higher (Hunter, 1988), particularly farther downstream.

An important additional wind process for the coastal waters is diurnal land and sea

breezes. These can exhibit speeds of the same magnitude as those brought about by

normal synoptic systems (Hunter, 1988). Hunter (1981) has used offshore wind

observations to show that land breezes can here extend at least 60 km seaward. The

direction of these winds may have a decided influence on cloud formation,

precipitation over the shelf as well as coastal runoff.

As mentioned before, it has been demonstrated that cumulus cloud lines frequently

form over the northern Agulhas Current (Lutjeharms et al., 1986b; Lee-Thorp et al.,

1998) but mostly when the winds are along-current, from the north-east. During such

along-current air motion there is an enormous uptake of moisture from the current

(Lee-Thorp et al., 1999; Rouault et al., 2000). About 5 times as much water vapour is

transferred to the atmosphere above the current itself than from ambient waters.

During on-shore winds this moisture is advected inland and may contribute

significantly to moisture convergence and rainfall over the interior of South Africa. In

fact, it has been shown that this leads to local intensification of storm systems and the

concurrent flood events (Rouault et al., 2002). To what extent this leads to measurable

dilutions of coastal waters by river runoff is not known. What is known is that the

presence of the Agulhas Current has a consistent effect on coastal rainfall all along its

Fig. 20-012 The influence on coastal rainfall of the distance of the core of the

Agulhas Current from the coastline. (After Jury et al., 1993.) The abscissa gives

the distance upstream from Port Elizabeth (see Fig. 20-011). The solid curve

gives the distance from the coast to the core of the Agulhas Current as expressed

25

by sea surface temperatures. Note that the distance is greater off the Agulhas

Bank (0 km) and at the Natal Bight (800 km). The broken line shows the coastal

rainfall. Both curves are expressed as standardized departures; that of the

distance from the coast having been inverted for comparison.

northern part (Jury et al., 1993; Fig. 20-012). Wherever the current is close to the

coast, such as between Durban and Port Elizabeth, the rainfall is enhanced; wherever

the current axis diverges from the coastline, such as at the Natal Bight and at the

southern part of the Agulhas Current, coastal rainfall is significantly reduced. This is

not the only process that makes the Natal Bight an unusual shelf region.

4.2 The Natal Bight

The Natal Bight is formed by a landward offset between Richard's Bay and

Durban in an otherwise rather linear coastline (Fig. 20-011). The northern part of the

bight is shallower than 50 m; the southern part deeper. There are some well-

developed canyons in the bathymetry of the continental slope, but these do not extend

onto the shelf, where they have been filled in by sediment (Martin and Flemming,

1988). The major depocentre of the region is the offshelf Tugela Cone (viz. Fig. 20-

013), evidence that the Tugela River is the major source of sediment for this shelf

region. Sediments over the shelf itself consist largely of sand. The percentage is in

excess of 75% over all parts of the Natal Bight shelf except seaward of the Tugela

River (Flemming and Hay, 1988) where mud is the dominant sediment type. Gravel

patches are found largely, but not exclusively, at the shelf edge where scouring from

the Agulhas Current is to be expected. The distribution of sediments (Flemming and

Hay, 1988) is particularly instructive here since it gives a clear indication of the

integrated movement of the bottom waters where other data may not be available.

Fig. 20-013 A conceptual model of the bedload movement on the continental

shelves adjacent to the northern Agulhas Current. (After Flemming and Hay,

1988.)

26

The shelf directly equatorward of the Natal Bight has, for instance, seen hardly any

hydrographic investigations. However, the general bedload dispersal model suggests

that the shelf waters move equatorward here, in clear disagreement with the concept

of a straightforward Mozambique-Agulhas Current continuity. A bedload parting is

found at about 28 °S (Fig. 20-013). Analyses of ships' drift (Harris, 1978) indicate

that poleward of this point the currents over the shelf follow the Agulhas Current 75%

of the time. This implied movement is consistent along the whole coastline except just

downstream of Durban where it again is equatorward. This latter discrepancy may be

due to an embedded lee eddy that is a recurring feature of the circulation at this

location just south of the Natal Bight (e.g., Anderson et al., 1988; Meyer et al., 2002)

and will be discussed in greater detail below.

The submarine bedform distribution is even more instructive. Active submarine

dune fields, moving with the current, are found north of the Natal Bight and along the

shelf break of the northernmost half of the bight. Along the southern half of the shelf

break there is no evidence of the influence of the current, suggesting that it overshoots

here (viz. Fig. 20-011), maintaining some distance from the shelf edge and thus not

affecting the sediments. It is intriguing that off Durban the movement of the mobile

dune field is, by contrast, northward, substantiating the persistence of the lee eddy

surmised to occur here (Pearce et al., 1978; Meyer et al., 2002). Flemming and Hay

(1988) have inferred a complex shelf circulation from the sediment distributions and

the bedforms, consisting of a cyclonic movement over the northern, shallower part of

the bight and a dipolar structure of an inner anticyclonic and an outer cyclonic eddy

over the southern, deeper parts. What is in fact known about the circulation here?

First, the presence of a persistent upwelling cell at the upstream end of the Natal

Bight is the most prominent part of the hydrodynamics of the shelf waters of the Natal

Bight and a fundamental key to understanding the ecosystem of this shelf sea. From

all other perspectives it may be considered to be a semi-enclosed system. The strong

and ever-present Agulhas Current at the shelf edge forms a formidable barrier to

exchanges of water and biota with the open ocean. At the northern end of the bight,

between Richard's Bay and Cape St Lucia, the shelf widens as the current sweeps

poleward. This bathymetric arrangement is believed to lead to topographically

induced upwelling (Gill and Schumann, 1979), as it does elsewhere along the

trajectory of the Agulhas Current.

In this general region sea surface temperatures are about 26 °C in the summer

months, peaking in February (Pearce, 1978) and dropping to about 21 °C in August.

Observations of sea surface temperature in the region (Gründlingh, 1974; Gründlingh

and Pearce, 1990) have shown that off Richard's Bay the temperatures are always a

few degrees lower. As could be expected, the water here is largely Tropical Surface

Water with only the occasional presence of Subtropical Surface Water (Pearce, 1978).

Others (Lutjeharms et al., 2000c) have shown that the purest Subtropical Surface

Waters is found on the shelf edge off Richard's Bay and St Lucia. This sporadic

presence of Subtropical Surface Water on the shelf, otherwise found at depths of 150

m or more offshore (Pearce, 1977b), is highly suggestive. Subsequent investigations

using satellite images (Lutjeharms et al., 1989b) and a dedicated hydrographic cruise

(Lutjeharms et al., 2000c; Meyer et al., 2002) have demonstrated unequivocally that

this is indeed a persistent upwelling cell.

Lower temperatures are observed here more or less continuously, although the

areal extent of the surface expression may vary considerably. This surface expression

seems to have no clear seasonal pattern, neither is it clearly related to potential

27

upwelling inducing winds (Lutjeharms et al., 1989b). Pearce (1978) has shown that

evidence of 16 °C water (Subtropical Surface Water, viz. 20.3) at depths of 125 m,

sometimes less than 100 m depth, on the shelf is intermittent, with no clear pattern. It

can therefore be accepted that this upwelling is not wind-driven. The effect of this

upwelling can be observed at the sea surface along the inner edge of the Agulhas

Current as far downstream as Durban as the colder surface water is dragged

southward as a cool filament (Lutjeharms et al., 1989b). Further evidence for the

nature of this upwelling cell comes from nutrient distributions (Carter and d'Aubrey,

1988; Meyer et al., 2002; Fig. 20-014). It shows that the influence of the upwelling

cell extends over a sizeable part of the bight. Carter and d'Aubrey (1988) have given

historical nutrient values all over the bight and state that there is no clear seasonal

pattern in the occurrence of nutrients. Vertical sections show clearly (Lutjeharms et

al., 2000c) that this nutrient-rich water is upwelled at the St Lucia upwelling cell and

from there moves over the floor of the bight southwards. Further evidence for the

effect of this upwelling cell comes from biological observations.

Fig. 20-014 Distribution of dissolved nitrate at 10 m depth over the Natal Bight

during July 1989. (After Meyer et al., 2002.) Dots represent station positions.

28

The shelf shallower than 200 m has been shaded. The presence of an active

upwelling cell equatorward of Richard's Bay is evident.

The distribution of chlorophyll-a exhibits a very similar pattern to that of the

nutrients (e.g., Meyer et al., 2002), with the enhanced values slightly lower very close

to the coast, implying an active upwelling process taking place during the

observations. Oliff (1973; as quoted by Carter and Schleyer, 1988) has shown how the

phytoplankton production reacts almost instantaneously to an upwelling event at

Richard's Bay. Reviews of the plankton, zooplankton as well as the benthic species

found in the Natal Bight have been given by Carter and Schleyer (1988) and by

McClurg (1988) respectively. These studies were based on information that was

geographically very inhomogeneous, since they had to depend on an eclectic set of

previous collections not designed uniformly to cover the shelf as a whole. From these

scattered observations it is impossible to infer the extent of the biological influence of

the St Lucia upwelling cell over the Natal Bight shelf, particularly over the southern

part.

The waters of the poleward part of the Natal Bight are by contrast unspectacular

and fit well into the ranges, both physical and biological, to be expected at these

latitudes. The nutrients are low (Carter and d'Aubrey, 1988; Meyer et al., 2002),

coming from Tropical Surface Waters. The nutrient concentrations are 1.01 1.86

mol/ (nitrate), 0.48 0.72 mol/ (phosphate) and 3.50 4.69 mol/ (silicate) at

10 m depth. The values on this part of the shelf do not exhibit great differences from

those found in the surface waters of the Agulhas Current. The exception is to be found

close to the Tugela River mouth (viz. Fig. 20-011) where values of all nutrients are

higher during floods and chlorophyll-a values are enhanced (Carter and Schleyer,

1988). This is reflected in greater densities of fish larvae at such times (Beckley and

van Ballegooyen, 1992). When this outflow was directly observed during such a flood

event, the indications were that most of the outflow occurred at a depth of 30 m and

extended at least 25 km offshore. Salinities and temperatures over the shelf otherwise

closely follow those of the Agulhas Current itself, also its seasonal cycle.

The circulation in the southern part of the bight is much harder to establish.

Remote sensing has suggested a cyclonic eddy (Malan and Schumann, 1979) and this

has been considered the main element in many conceptual portrayals ever since (e.g.,

Pearce, 1977b, Gründlingh and Pearce, 1990; Schumann, 1987; Harris, 1978).

Observations show (Pearce, 1977b) that close to the coast the currents only follow the

Agulhas Current 50% of the time. Ship's drift close inshore (1.6 km) is also about

equally divided between poleward and equatorward drift (Harris, 1964; Pearce et al.,

1978), agreeing with wind frequencies. The closer to the current, the greater the

tendency is to follow its direction closely (Harris, 1978). The only quasi-synoptic

hydrographic survey of the bight as a whole (Lutjeharms et al., 2000c) gives no

indication of a consistent circulation. There are indications that the location of the

edge of the Agulhas Current may show greater shifts in location along the edge of this

particular part of the shelf than farther up- or downstream (Gründlingh and Pearce,

1990) and that shear edge eddies may play an important role on occasions (e.g.,

Lutjeharms and Roberts, 1988; their Fig. 10b). Putting it all together, Pearce et al.

(1978) have concluded, on the basis of an eclectic set of observation, that "at any one

time a succession of eddies of a variety of scales (are) generated by shear processes or

meteorological forcing probably exists in the (Natal Bight)" and this is as good a

29

summary of what is currently known as data will allow. Directly south of the bight,

adjacent to the city of Durban (Fig. 20-011), the situation seems much simpler.

As mentioned above, a number of investigators (e.g., Pearce et al., 1978;

Schumann, 1982; Anderson et al., 1988; Lutjeharms et al., 2000c and Meyer et al.,

2002) have pointed out the presence of a cyclonic eddy directly off Durban, in the lee

of the broader shelf that forms the Natal Bight. Currents measured off Durban do

show a dominant north-eastward component (Fig. 20-015). Ship's drift close inshore

(1.6 km) is similar to further north on the shelf about equally divided between

poleward and equatorward drift (Harris, 1964; Pearce et al., 1978), which agrees with

wind frequencies. Drifters have shown the same bi-polar tendency. Results presented