United Nations

Environment Programme

Chemicals

Europe

Eur

REGIONAL REPORT

ope

RBA PTS REGIONAL REPOR

Regionally

Based

T

Assessment

of

Persistent

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals

11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Chātelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone : +41 22 917 1234

Fax : +41 22 797 3460

Substances

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

December 2002

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and

Printed at United Nations, Geneva

GE.03-00167January 2003500

Economics Division

UNEP/CHEMICALS/2003/3

G l o b a l E n v i r o n m e n t F a c i l i t y

UNITED NATIONS

ENVIRONMENT

PROGRAMME

CHEMICALS

Regional y Based Assessment

of Persistent Toxic Substances

Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech

Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Georgia, Germany, Hungary,

Ireland, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands,

Norway, Poland, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation,

Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, United Kingdom of Great

Britain and Northern Ireland

EUROPE

REGIONAL REPORT

DECEMBER 2002

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY

This report was financed by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through a global project with co-

financing from the Governments of Australia, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States of

America

This publication is produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound

Management of Chemicals (IOMC)

This publication is intended to serve as a guide. While the information provided is believed to be

accurate, UNEP disclaim any responsibility for the possible inaccuracies or omissions and

consequences, which may flow from them. UNEP nor any individual involved in the preparation of

this report shall be liable for any injury, loss, damage or prejudice of any kind that may be caused by

any persons who have acted based on their understanding of the information contained in this

publication.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations of UNEP

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning

the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), was established in

1995 by UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO and OECD (Participating Organizations), following

recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development to strengthen

cooperation and increase coordination in the field of chemical safety. In January 1998, UNITAR formally

joined the IOMC as a Participating Organization. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of

the policies and activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the

sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the environment.

Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested together with a

reference to the document. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to

UNEP Chemicals.

UNEP

CHEMICALS

UNEP Chemicals11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Chātelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 917 8170

Fax:

+41 22 797 3460

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and Economics Division

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE ....................................................................................................................................................... VI

EXECUTIVE SUMMMARY............................................................................................................................VII

1.

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1

1.1.

BACKGROUND................................................................................................................................ 1

1.2.

OVERVIEW OF THE RBA PTS PROJECT ..................................................................................... 1

1.2.1. Objectives ............................................................................................................................1

1.2.2. Results..................................................................................................................................2

1.3.

METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................. 2

1.3.1. Regional

divisions................................................................................................................2

1.3.2. Management

structure..........................................................................................................2

1.3.3. Data

processing....................................................................................................................2

1.3.4. Project

funding.....................................................................................................................3

1.4.

SCOPE OF THE EUROPEAN REGIONAL ASSESSMENT........................................................... 3

1.4.1. Introduction..........................................................................................................................3

1.4.2. Omissions/weaknesses.........................................................................................................3

1.4.3.

Other European Assessment projects...................................................................................4

1.5.

GENERAL DEFINITIONS OF CHEMICALS.................................................................................. 5

1.5.1.

Persistent Toxic Substances.................................................................................................5

1.5.2. Pesticides..............................................................................................................................5

1.5.3. Industrial

Chemicals ............................................................................................................8

1.5.4. Unintended

by-products.......................................................................................................9

1.5.5.

Other PTS of emerging concern in Europe..........................................................................9

1.6.

PHYSICAL SETTING ..................................................................................................................... 15

1.6.1. Physical/geographical

description of the terrestrial Europe ..............................................15

1.6.2.

Climate and meteorology...................................................................................................16

1.6.3. European

freshwater

environments....................................................................................16

1.6.4. European

marine

environment...........................................................................................17

1.7.

PATTERNS OF DEVELOPMENT/SETTLEMENT....................................................................... 18

1.8.

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................................. 19

2.

SOURCES OF PTS ............................................................................................................................... 22

2.1.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION TO PTS SOURCES................................................................ 22

2.2.

DATA COLLECTION AND QUALITY CONTROL ISSUES....................................................... 22

2.2.1. Introduction........................................................................................................................22

2.2.2. Emission

inventories..........................................................................................................22

2.2.3. Conceptual

approach..........................................................................................................23

2.3.

PESTICIDES.................................................................................................................................... 24

2.3.1. Aldrin .................................................................................................................................24

2.3.2. Chlordane...........................................................................................................................24

2.3.3. DDTs..................................................................................................................................25

2.3.4. Dieldrin ..............................................................................................................................25

2.3.5. Endrin.................................................................................................................................25

2.3.6. Heptachlor..........................................................................................................................25

2.3.7. Hexachlorobenzene............................................................................................................25

2.3.8. Mirex..................................................................................................................................26

2.3.9. Toxaphene..........................................................................................................................26

2.4.

INDUSTRIAL CHEMICALS .......................................................................................................... 26

iii

2.4.1. Polychlorinated

biphenyls..................................................................................................26

2.5.

UNINTENDED BY-PRODUCTS ................................................................................................... 27

2.5.1. Dioxins

and

furans .............................................................................................................27

2.6.

OTHER PTS OF EMERGING CONCERN IN EUROPE ............................................................... 28

2.6.1. Brominated

flame

retardants..............................................................................................28

2.6.2. Lindane

(-HCH) ...............................................................................................................28

2.6.3. Organic

mercury ................................................................................................................29

2.6.4. Organic

tin .........................................................................................................................29

2.6.5. Pentachlorophenol..............................................................................................................29

2.6.6.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.....................................................................................30

2.6.7.

Short chain chlorinated paraffins .......................................................................................32

2.6.8. Hexabromobiphenyl...........................................................................................................34

2.7.

CONLUSIONS................................................................................................................................. 34

2.8.

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................................. 35

3.

ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGICAL AND ECOTOXICOLOGICAL

CHARACTERISATION ....................................................................................................................... 37

3.1.

LEVELS AND TRENDS ................................................................................................................. 37

3.1.1. Introduction........................................................................................................................37

3.1.2. Air ......................................................................................................................................37

3.1.3. References..........................................................................................................................41

3.1.4. Deposition ..........................................................................................................................43

3.1.5.

Snow and ice ......................................................................................................................45

3.1.6. Aquatic

ecosystems............................................................................................................45

3.1.7. Terrestrial

ecosystems........................................................................................................59

3.1.8. Hot

spots ............................................................................................................................67

3.1.9. Conclusions........................................................................................................................72

3.2.

ECOTOXICOLOGY OF PTS OF REGIONAL CONCERN .......................................................... 74

3.2.1. Introduction........................................................................................................................74

3.2.2.

Overview of harmful effects ..............................................................................................74

3.2.3.

Mechanisms of harmful effects..........................................................................................74

3.2.4.

Ecotoxicological effects on the particular types of biota...................................................77

3.2.5.

Ecotoxicological databases and laboratory and field studies.............................................79

3.2.6. Data

gaps............................................................................................................................80

3.2.7. References..........................................................................................................................81

3.3.

HUMAN EFFECTS OF PTS OF REGIONAL CONCERN............................................................ 85

3.3.1. Introduction........................................................................................................................85

3.3.2.

Overview of harmful effects ..............................................................................................86

3.3.3.

National and regional human health effects reports...........................................................88

3.3.4. Conclusions........................................................................................................................90

3.3.5. References..........................................................................................................................90

3.4.

HUMAN EXPOSURE TO PTS COMPOUNDS IN REGION III EUROPE ............................... 92

3.4.1. Introduction........................................................................................................................92

3.4.2. PCBs ..................................................................................................................................93

3.4.3. PCDD/Fs ............................................................................................................................95

3.4.4. HCB ...................................................................................................................................99

3.4.5.

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers.......................................................................................100

3.4.6. Conlusions........................................................................................................................100

3.4.7. References........................................................................................................................101

4.

ASSESSMENT OF MAJOR PATHWAYS OF CONTAMINANTS TRANSPORT......................... 103

4.1.

GENERAL FEATURES ................................................................................................................ 103

iv

4.2.

REGION SPECIFIC FEATURES.................................................................................................. 104

4.3.

OVERVIEW OF EXISTING MODELLING PROGRAMMES AND PROJECTS ...................... 104

4.3.1. Introduction......................................................................................................................104

4.3.2. Steady

state

models..........................................................................................................104

4.3.3. Dynamic

models ..............................................................................................................105

4.4.

EMEP/MSCE-POP MODEL A MODEL USED IN THE REGION .......................................... 107

4.4.1. Introduction......................................................................................................................107

4.4.2. Benzo(a)pyrene

(B(a)P) ...................................................................................................108

4.4.3.

-HCH ..............................................................................................................................111

4.4.4. Polychlorinated

biphenyls................................................................................................113

4.4.5. Hexachlorobenzene

(HCB) ..............................................................................................114

4.4.6. PCDDs/Fs ........................................................................................................................116

4.5.

EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE FOR LONG-RANGE TRANSPORT (LRT) ............................. 118

4.6.

CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................ 120

4.7.

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................... 121

5.

PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE REGIONAL CAPACITY AND NEED

TO MANAGE PTS ............................................................................................................................. 123

5.1.

INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 123

5.2.

MONITORING CAPACITY ......................................................................................................... 123

5.2.1. Introduction......................................................................................................................123

5.2.2.

Existing regional monitoring programmes ......................................................................124

5.2.3. Local

monitoring..............................................................................................................125

5.3.

EXISTING REGULATION AND MANAGEMENT STRUCTURES ......................................... 125

5.3.1. International .....................................................................................................................125

5.3.2. Regional ...........................................................................................................................125

5.4.

WHITE PAPER ON THE COMMISSION ON A NEW CHEMICALS POLICY IN EUROPE .. 127

5.4.1. National............................................................................................................................128

5.5.

STATUS OF ENFORCEMENT .................................................................................................... 128

5.6.

ALTERNATIVES OR MEASURES FOR REDUCTION............................................................. 128

5.7.

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ....................................................................................................... 131

5.8.

IDENTIFICATION OF NEEDS .................................................................................................... 132

5.9.

CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................ 134

5.10.

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................... 134

CONCLUSIONS .............................................................................................................................................. 134

ANNEX I ..................................................................................................................................................... 143

v

PREFACE

The production of this report was made possible through a co-operation of many regional experts, EC, regional

government and institutions.

Number of project: GF/CP/4030-00-20, Number of subproject: GF/XG/4030-00-86

Implementation: Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

The project manager for this study was Prof. Dr. Ivan Holoubek, RECETOX TOCOEN & Associates, Brno, Czech

Republic.

Regional Team: Ruth Alcock (UK), Eva-Brorström-Lundén (SE), Anton Kocan (SK), Valeryj Petrosjan (RU), Ott Roots

(EE), Victor Shatalov (RU)

Team of regional experts: Zarema Amirova (RU), Aake Bergman (SE), Andreas Beyer (GE), Ludk Blįha (CR), Peter

Bureaul (GE), Peter Coleman (UK), Pavel Cupr (CR), Sergey Dutchak (RU), Jan Duyzer (NL), Jerzy Falandysz (PL),

Christine Fuell (HELCOM), Emanuel Heinisch (GE), Irena Holoubkovį (CR), Kevin Jones (UK), Antonius Kettrup

(GE), Jiķ Kohoutek (CR), Svetlana Koroleyva (RU), Michal Krzyzanowski (WHO-Europe), Roland Kubiak (GE),

Gerhard Lammel (GE), Andre Lecloux (B/EUROCHLOR), Miroslav Machala (CR), Alexander Malanichev (RU),

Michael McLachlan (GE), Janina Lulek (PL), Anna Palm (SE), Andy Sweetman (UK), Dick van de Meent (NL),

Martin van den Berg (NL), Jan Vanderbroght (GE), John Vijgen (D), Peter Weiss (AT), Sabine Wenzel (GE)

In 2000, The United Nations Environmental Program asked this Regional Team to participate in a global

assessment of PTS, in particular to produce a report on PTS in the European region. This document is intended

to meet that request. The report is one of twelve, which make up the global assessment.

The authors are grateful to the all reviewers for their critiques and advice.

Ivan Holoubek

RECETOX / TOCOEN & Associates

Kamenice 126/3

625 00 Brno

Czech Republic

holoubek@recetox.muni.cz

The preparation of this report and meeting of Regional team and Technicals Workshops were also partly covered by

EUROCHLOR/CEFIC; Masaryk University Brno, CR; TOCOEN, s.r.o. Brno, CR and Czech-Moravian Cement, a.s., CR.

vi

EXECUTIVE SUMMMARY

1. INTRODUCTION

There is a need for a scientifically-based assessment of the nature and scale of the threats to the environment

and its resources posed by persistent toxic substances that will provide guidance to the international community

concerning the priorities for future remedial and preventive action. The assessment will lead to the

identification of priorities for intervention, and through application of a root cause analysis will attempt to

identify appropriate measures to control, reduce or eliminate releases of PTS, at national, regional or global

levels.

The objective of the project is to deliver a measure of the nature and comparative severity of damage and

threats posed at national, regional and ultimately at global levels by PTS. This will provide the GEF with a

science-based rationale for assigning priorities for action among and between chemical related environmental

issues, and to determine the extent to which differences in priority exist among regions.

The project relies upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and information as the basis for the

assessment. No research will be undertaken to generate primary data, but projections will be made to fill

data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment. The proposed activities are designed to obtain

the following expected results:

1.

Identification of major sources of PTS at the regional level;

2.

Impact of PTS on the environment and human health;

3.

Assessment of trans-boundary transport of PTS;

4.

Assessment of the root causes of PTS related problems, and regional capacity to manage these

problems;

5.

Identification of regional priority PTS related environmental issues; and

6.

Identification of PTS related priority environmental issues at the global level.

The outcome of this project will be a scientific assessment of the threats posed by persistent toxic substances to

the environment and human health. The activities to be undertaken in this project comprise an evaluation of the

sources of persistent toxic substances, their levels in the environment and consequent impact on biota and

humans, their modes of transport over a range of distances, the existing alternatives to their use and remediation

options, as well as the barriers that prevent their good management.

2. SOURCES OF PTS

Persistent Toxic Substances (PTS) can be introduced into the environment via numerous sources and activities.

Point and diffuse sources include releases from industrial and domestic sites, traffic, waste disposal operations

such as incinerators and landfills. Secondary sources include the spreading of sludge on land and remobilisation

of previously deposited compounds from soils and water bodies. Some sources are capable of regulation (such

as industrial point sources) while other diffuse emissions represent unregulated and/or difficult to regulate

inputs (fugitive releases from landfills, domestic open burning of waste).

During the last decade a large amount of progress has been made in the production of atmospheric emission

inventories of several PTS compounds within Europe. However there is still a lack of comparability in

inventories produced by various organisations for the same compound group and this reduces transparency

when comparing or compiling inventories. Improved emission inventories for PTS have become increasingly

important as emission or source driven fate models for regional and global scales are developed. Inventories

serve as useful information for decision makers in order to reduce the impact of these pollutants on the

environment.

Source inventories represent a crucial step in developing appropriate risk control strategies for PTS using an

inventory of releases to air, water or land it is possible to rank sources in order of importance and so target

source reduction measures effectively and incorporate effective risk reduction measures.

During the last two decades there has been a growing interest within environmental research community to

understand the fluxes, behaviour, fate, and effects of PTS compounds. Various studies and assessments of PTS

vii

in the environment have been carried out by several international organisations, such as United Nations

Environmental Programme (UNEP), the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN ECE), the

World Health Organisation (WHO), the Nordic Council of Ministers, the Paris and Oslo Commissions, the

Helsinki Commission, and the Great Lakes Commission, as well as the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment

Programme (AMAP).

Conlusions

· Within the Region as a whole there is a large amount of data relating to industrial point source

emissions to the atmosphere. Sources to air of well studied compounds such as PAHs, PCBs, and

PCDDs/Fs are generally well characterised and inventories have been calculated and updated regularly

via EMEP. Due to restrictions on the manufacturing and more stringent control of releases, emissions

from primary sources have been declining during the last 20 years. Understanding of secondary source

inputs and the potential for environmental recycling of individual compounds continues to be limited

and few measurements are available.

· Obsolete stocks of pesticides represent a potential source of PTS material particularly within the

Central European Countries and Newly Independent States. Exact quantities and components of the

stockpiled wastes are unknown at present but quantities are thought to be in excess of 80 000 t.

· For the compounds of emerging concern (e.g. PBDEs, chlorinated parrafins) emission sources to all

environmental compartments are very poorly characterised, few formal inventories have been

established and there is limited understanding of the principal contemporary source categories. For

PBDEs, evidence of increasing concentrations in human tissues from Sweden would suggest that

emissions into the Region have been rising during the last 20 years.

· Unlike sources to air, sources to land and water are very poorly quantified for all the PTS compounds.

· Prioritization of sources inputs within the Region as a whole highlight that the following compounds

represent ongoing releases in the Region which are of most concern with respect the environment and

health:

-

Hexachlorobenzene (HCB)

-

PCBs

-

PCDD/Fs

-

PCP

-

PBDEs

-

Short chain chlorinated paraffins

3. ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGICAL AND ECOTOXICOLOGICAL

CHARACTERISATION

3.1 Levels and trends

The first part of this chapter deals with the environmental levels and trends. The relative spatial and temporal

variations in environmental concentrations of PTSs are briefly described. The following sections describe

ecotoxicology, toxicology and human exposure to PTS in Region III.

Conclusions

· Region III has a lot of information concerning to environmental levels of PTS, but geographic

distribution of the available data is not equal for all parts of Region, better situation is in some

countries of EU and Central Europe.

· Very good and traditional monitoring system concerning also PTS exists (EN ECE EMEP, OSPAR,

HELCOM) which are oriented to air and deposition (EMEP), seas (OSPAR, HELCOM); some new are

ongoing (Caspic Sea, Black Sea). As far as rivers, the monitoring is realised mainly based on the

national level, but a lot of multinational or regional activities already exist (Rhine, Danube).

· The measurements of PTS levels in some other compartments such as lakes, soils or vegetation is

partly performed based on the international programmes (IM EMEP), national monitoring programmes

(soils) or pilot or research projects (biota, lakes). Human exposure is measured and studied on the

European levels (activities WHO Europe) and very frequently on the national levels.

viii

· Although monitoring indicates that the loads of some hazardous substances have been reduced

considerably over the past ten years especially in the Baltic Sea region, problems still persist.

Comprehensive knowledge about the impact of most available chemicals, and their combinations, on

human health and the environment is still lacking.

· The increasing number of these man-made substances is a matter of concern and calls for the

application of the precautionary principle. On the other hand other seas, such as Black or Caspic still

have a lot of heavily contaminated sites, where petroleum hydrocarbons and phtalates are the dominant

organic contaminants of the Caspian Sea. Only traces of persistent organochlorines were detected in the

Caspian seals (highest section of the food web). But also the level of contamination of the Caspian Sea

decreased significantly during the last 10 years.

· The loads of many substances have been reduced by at least 50 % since the late 1980s - mainly due to

the effective implementation of environmental legislation, the substitution of hazardous substances

with harmless or less hazardous substances, and technological improvements.

· In former communistic countries reductions have been mainly due to fundamental socio-economic

changes.

· The organochlorinated pesticides (OCPs) are no longer in use, have never been used, or have even been

banned within the Region III. But one serious problem that remains is that in some countries various

obsolete pesticides still remain in temporary storage awaiting suitable disposal.

· Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are no longer produced or used in new ways. Inventories are still

being carried out in CEECs. Following an analysis of the legislative situation throughout the CEE part

of Region, and the current uses, stockpiles and releases of PCBs measures have been proposed to

ensure their safe handling and to reduce releases of PCBs from existing equipment.

· As a results of former production, long time and widespread use and also long-range transport from

other part of Globe, OCPs, PCBs, PCDDs/Fs and PAHs and also some newer PTS are found in all

environmental compartments including remote high mountain European sites, but principially the

decreasing trends are observed.

· In this context, it is important to remember that a lot of countries of Region, such as the UK, Germany

and others have a long industrial history, involving combustion activity in the form of wood and coal

burning. For example in the UK, over 65 million ton of coal was being burned each year nationally in

the 1850s. The smelting of metals and the production of iron and steel also have a long history in the

UK and Europe, processes known to have significant PCDDs/Fs emissions. It is important to remember

that the history of PCDDs/Fs environmental inputs/burdens in the UK and Europe may therefore not be

mirrored in other regions of the world.

· Several studies reported that air PCDDs/Fs levels are declining in urban/industrialized centres. These

trends are observed in Western Europe and are believed to be largely due to emission abatement actions

taken in the early nineties. The decline of PCDDs/Fs levels in the atmosphere resulted in a decrease of

these compounds in "atmospherically impacted" media such as vegetation, cow“s milk and meat

products. Moreover, the human dietary intake of dioxins and furans dropped by almost a factor of 2

within the past 7 years.

· Analyses showed a decrease in the concentrations of the PAH compounds in the particle-phase in the

ambient air during the second part of 80“s. This is a result of that the cars equipped with catalyst

engines became a mandatory 1991. Also improvement of the fuel and the increased use of district

heating, contribute to this trend. As far as the last 10 years, and the annual average concentrations of

PAHs seem to stagnate due to a permanent increase of motorized traffic on the one hand and a better

combustion technology and an increase in the use of natural gas for domestic heating on the other hand.

· Relatively worse situation can be observed in the towns in the former communistic countries, where the

number of cars dramatically increased after the political changes. The same problems have all larger

cities in CEE countries after the political changes extremely high increase of town traffic and

decreasing contribution from former industrial sources as the result of falling-off of production.

3.2 Ecotoxicology of PTS of regional concern

This chapter describes the effects in organisms other than humans, which have been proved for region Europe

III by means of special research. The term "ecotoxicology" will be used to discuss the effects of persistent toxic

substances (PTS) on both the aquatic and terrestrial biota.

Conclusions

ix

· Analysis of the observed ecotoxicological effects of PTS on birds, mammals and fish in Europe has

shown, that although a wide number of laboratory and manipulated in situ studies with various

organisms and effects were conducted and are documented in the literature, one has to carefully and

critically evaluate these data.

· On one hand, the controlled laboratory toxicological studies with individual compounds or carefully

prepared mixtures usually allow clear dose-response causality between chemical exposure and

observed effects to be defined.

· On the other hand, laboratory tests alone seldom adequately describe what is likely to occur in the

environment. The often complex and subtle effects of chronic, low-level environmental exposure to

PTS are less well understood.

· In the environment, the universal exposure of organisms to low levels of a wide range of chemical

contaminants makes it extremely difficult to ascribe an observed effect to any particular one of them.

There is also the possibility that, in the environment, toxic substances in combination may act

additively, antagonistically or synergistically.

· PTS can act via different mechanisms and cause various adverse effects in wildlife. Mechanisms

causing ecotoxicological effects include non-specific toxicity (narcosis) and more specific mechanisms,

such as aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) mediated toxicity, steroid receptor dependent effects,

metabolic activations, immune suppression and neurotoxicity.

· The assessment of priority of PTS, included in the list of the Stockholm Convention, has been

performed by scoring them on the basis of data, available in the Region Europe-III.

· The second group of ecotoxicants, which were mentioned in the Stockholm Convention, was also

scored.

3.3 Human effects of PTS of regional concern

Many environmental epidemiological studies indicate that correlations do exist between chemical

contamination and observed human health effects. To evaluate critically the adverse effects of individual PTS,

it is necessary to compare data derived from experiments with the laboratory animals, the results of

epidemiological studies due to accidental or occupational exposure, as well as the effects observed for

,,average" population.

It is very difficult to elucidate cause and effect relationships between human exposure to low levels of a PTS in

the environment and the particular adverse health effects, not least because of the broad range of chemicals to

which humans are exposed at any one time. The measurable residues of PCBs, dioxins and various

organochlorine pesticides present in human tissues around the world and contamination of food, including

breast milk, is also the worldwide phenomenon.

Evidence for low-level effects of PTS on humans are more limited than those for wildlife but are consistent

with effects reported both in exposed wildlife populations and in laboratory experiments on animals. This is

why the data from ,,hot-spot" accidental events or occupational exposures can help to formulate the safety

values for PTS. Trying to elucidate the toxicological effects of PTS, one has always to remember about many

confounding factors affecting human health (life style, dietary habits), which are often very poorly evaluated.

Concluding the general introduction, it is worthwhile to mention, that WHO came to the conclusion, that

,,where levels of some PTS in breast milk approach or slightly exceed tolerable levels, breast feeding should not

be discouraged since the demonstrated significant benefits of this practice greatly outweigh the small

hypothetical risk that POPs may pose". This conclusion has been supported by the report of AMAP, the authors

of which suggest that consideration should be given to developing dietary advice to promote the use of less-

contaminated traditional food items, which will also maintain nutritional benefits.

Conclusions

· Analysis of the results of environmental epidemiological studies shows, that correlations do exist

between the chemical contamination of air, water and soil and human health. To elucidate the particular

effects of individual toxicants (genotoxicity, estrogenic effects, carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity,

immunotoxicity, etc.) it is important to compare the above mentioned results with the data, obtained

from experiments with the laboratory animals.

x

· The assessment of priority PTS, included in the list of the Stockholm Convention, has been performed

by scoring them on the basis of data, available in the Region Europe-III.

· The second group of toxicants, which were mentioned in the Stockholm Convention, was also scored.

3.4 Human exposure to PTS compounds in Region III Europe

The persistent bioaccumulative properties of PTS substances means, that they have the capacity to transfer

through terrestrial and aquatic foodchains and accumulate in human lipids. As omnivores we occupy a top

position in terrestrial and aquatic foodchains and as a result consume a high proportion of food in which

persistent lipophilic compounds will have effectively biomagnified. Once ingested, PTSs sequester in body

lipids, where they equilibrate at roughly similar levels on a fat-weight basis between adipose tissue, serum, and

breast milk.

It is possible to document three distinct types of human exposure to PTS compounds:

High-dose acute exposure: typically results from accidental fires or explosions involving electrical

capacitors or other PCB-containing equipment, or high dose food contamination.

Mid-level chronic exposure is predominantly due to the occupational exposure, and, in some cases,

also due to the proximity of environmental storage sites or high consumption of a PTS-contaminated

dietary source, such as fish or other marine animals.

Chronic, low-dose exposure is characteristic for the general population as a consequence of the

existing global background levels of PTSs with variations due to diet, geography, and level of

industrial pollution. Low level and population-wide effects are more difficult to study. People are

exposed to multiple PTSs during their lifetime and all individuals today carry detectable levels of a

range of PTSs in their body lipids.

Over the last 10-15 years as interest in exposure to these compounds has increased there have been numerous

surveys of both typical `background' levels in the population and also small surveys of occupationally exposed

individuals whose body lipids contain elevated concentrations.

Compounds are most often monitored in human milk, serum and adipose although milk monitoring is far more

widely practiced due to the relative ease of sample collection. Milk not only provides evidence of maternal

exposure to contaminants, it also provides information to assess risk to breast-fed infants. Contaminants in

breast milk for example increase with maternal age and decrease with the number and duration of lactation

periods (e.g. TCDD levels in breast milk decrease roughly 25% after each successive breast-fed child). The

most popular compounds for analysis include the OC pesticides and PCBs.

Numerous analyses have now been made of PCBs in samples of human milk from the general population

within the region. Countries with a long history of human tissue sampling - from the early 1980s - include the

Netherlands, Sweden and Germany. Within the Central European Countries, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and

Poland also have a sizeable database of information spanning the last 10-15 years. Standardized collection and

analytical protocols now exist for analysing many PTS compounds in breast milk in these countries in addition

to tissue banking facilities. For example, between 1986 and 1997 over 3 500 milk samples were analysed in

Germany for a range of organochlorine compounds. Far fewer analyses of human samples have been made for

PCDD/Fs, principally due to the high cost. As a general rule, travelling eastwards within the Region, the

number and size of data sets for all compounds reduces significantly.

Evidence from market basket surveys of principal foods and food groups suggest that exposure to many of the

classical PTS compounds via food is very similar throughout the Region. This is also supported by the

extensive movement of food products throughout Europe providing many consumers with a `European'

average food basket of produce. To a large extent personal choices in food preferences will ultimately control

our intake of persistent compounds throughout life. Since aquatic foodchains are subject to a greater loading of

many pollutants than terrestrial ones, individuals who consume fish and seafood obtain an appreciable

proportion of their annual intake via this route. For example, fishermen on the east coast of Sweden who have

eaten fatty Baltic fish (herring and salmon) almost daily were found to have roughly twice the blood levels of

DDT, PCBs and dioxins than people with a more average fish intake.

European exposure to dioxins via food has declined considerably during the last decades. This is due to

successful efforts that have led to the reduction of many known dioxin sources. Today the estimated intake by

the European population of PCDDs/Fs and non-ortho PCBs, expressed as WHO-TEQs, is 1.2-3.0 pg.kg-1

xi

bw.day-1. Since the 80“s various tolerable daily intake ,,recommendations" have been used, and for many

population groups, such as new-borns and high fish consumers, these recommendations have been exceeded,

and still are. Recently a tolerable weekly intake (TWI) of dioxins, furans and non-ortho PCBs, corresponding to

14 pg WHO-TEQ.kg-1 bw, was set by the EU Scientific Committee on Food (SCF).

The SCF has, as of 2002, established maximum limit values for dioxins and furans in consumer food on the

European market in order to reduce the overall dioxin contamination of the food-chain, and the exposure of the

European population. The goal is to have a 25 % decline in the exposure by year 2006. The WHOPDDDs/Fs-TEQ

maximum limits, based so far on the concentrations of PCDDs/Fs only, are set for foods such as meat, fish,

poultry, dairy products and oil and fats and range from 0.75-6 pg.g-1 lipid. With one exception the

WHOPDDDs/Fs-TEQ maximum limit is set on lipid basis, namely for fish. For fish the EU limit is 4 WHOPDDDs/Fs-

TEQ.g-1 fresh weight.

The absolute and relative contributions of PCDDs/Fs and non-ortho and mono-ortho PCBs to the total WHO-

TEQs of six foods chicken, beef, butter, human milk, salmon and cod liver from Northern Europe, were

determined and compared to the current EU limit values. For all foods studied, PCBs contribute to more than

50 % to the total WHO-TEQ. For cod liver the contribution of PCBs to the total WHO-TEQ is high at more

than 80 %. Sum TEQ levels in the salmon and cod liver reflects the relatively highly contaminated aquatic

food-chain.

Conclusions

· In summary, human exposure to PTS compounds in dominated by intake via terrestrial and aquatic

food products which have high lipid content and have been subject to bioaccumulation within

agricultural foodchains e.g. milk, meat, eggs and fish, (particularly oily and/or long-lived species).

Exposure is generally well characterized and quantified for PCBs and PCDD/Fs and a range of

organchlorine pesticides. The vast majority of adult exposure will be below current WHO guideline

values. Individuals exceeding the guideline value will be dominated by subsistence fishermen and their

families, individuals who consume several meals of oily fish each week in addition to those consuming

locally produced foods in the vicinity of an on-going source of contamination.

· Human lipid concentrations of well characterized compounds such as PCBs and PCDD/Fs have been

declining significantly in recent years throughout the Region at a rate of approximately 5% per year

since the early 1990s. This decline coincides with European restrictions on the manufacture and release

of these compounds into the environment and in particular, into the atmosphere. For some PTS

compounds of emerging concern such as PBDEs, there is some evidence of increasing trends in human

breast milk during the last 20 years.

· Breast-fed infants represent a distinct sub-group of the population whose exposure to PCDD/Fs and

Dioxin-like PCBs will exceed current guideline values based on bodyweight for the first few months of

life. In view of the significant declining trends in TEQ concentrations in breast milk over the last 20

years, WHO strongly recommend that breast feeding is encouraged and promoted for the child benefit.

4. ASSESSMENT OF MAJOR PATHWAYS OF CONTAMINANTS TRANSPORT

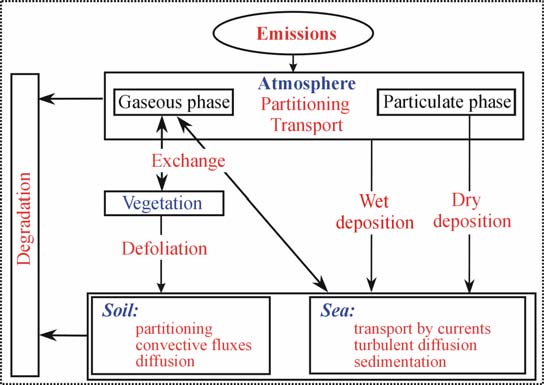

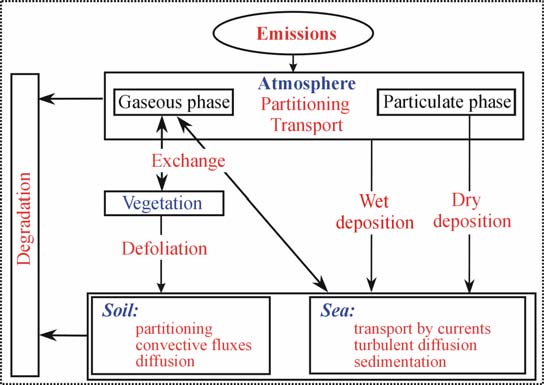

As many persistent toxic substances are semivolatile, their atmospheric transport can occur either in the gas

phase or in the particle phase of the atmosphere. Due to their low vapour pressure, PTSs tend to partition

mainly into organic carbon containing media, such as soil, sediment, biota or aerosols. However, their volatility

is often high enough to allow for long-range transport in a way that has been described as the "grasshopper

effect". This means that the chemical is trapped in an organic phase without being degraded, and is then

released back into the atmosphere, allowing for a short transport, after which it is trapped again and the

procedure continues until the chemical is ultimately degraded. This "grasshopper effect" allows persistent

chemicals of low vapour pressure to be transported long distances to areas where they have never been used,

which is of concern both for ethical and environmental reasons. Transboundary movement may also be possible

via large water bodies, where chemicals of low water solubility can be transported a long way via water

particles and suspended sediment material or chemicals with high water solubility can be very effectively

transported in the dissolved state. Migrating fish could also contribute to this phenomenon.

Regardless of in which medium a chemical is being transported, what ultimately determines a chemical's

potential of long-range transport and thus transboundary movement are its partitioning properties in

combination with the nature of the environmental media in or between which the transport occurs. Therefore,

xii

crucial in order to achieve an adequate description of a chemical's movement, is to create a picture, which

accurately describes the possible transport pathways that a chemical substance can undergo. This is a

complicated task, since the complexity of the environment cannot be underestimated. As a first approach, the

environment can however be divided into basic units, or compartments, which might include air with aerosols,

water with water particles, soil, sediment and vegetation, or other significant media. The aim is then to achieve

a description of transport processes and to derive a full picture of the movement of chemicals within the region

being assessed.

Today, most PTS are banned and not "primarily" emitted in the European region. Transboundary air transport

has been shown to be important for the occurrence of these chemicals in northern Europe. Atmospheric

deposition is an important pathway for PTS to both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. The cold climate in the

northern part of the region may favour the deposition of the PTSs. Environmental compartments, such as

vegetation, soil and sediments, will act as reservoirs for PTSs. In this region, contaminated sites, so-called "hot

spots", will also constitute as significant reservoirs for PTSs. PTSs may be re-emitted back from the ecosystem

to the atmosphere and be transported both within and from the region into the Arctic areas (grasshopper effect).

Conclusions

· Transboundary transport is important for the occurrence of PTS in the European region. Atmospheric

transport processes are important pathways for PTS to both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

· The evidence of LTR in the region has been investigated both with measurements and modelling.

· An integrated monitoring/modelling approach is applied for assessment of PTS contamination in the

European region. This approach includes arrangement of superstation network, model assessment of

contamination levels and national measurement campaigns. In modelling activities accumulation in

the compartments other than atmosphere is important.

· At present there exist a lot of multicompartment PTS transport models both steady-state and dynamic

describing PTS fate in the environment. In the framework of LRTAP Convention the EMEP/MSCE-

POP model is used for assessment of PTS contamination in the region.

· Modelling activities are useful for evaluation of PTS redistribution between various environmental

compartments, long-term trends of environmental contamination, spatial distribution of

concentrations in different media (atmosphere, soil, seawater, vegetation) and transboundary

transport.

· Some PTS possess very high long-range transport potential and hemispheric/global scale is reasonable

for them to assess European contamination. The hemispheric version of EMEP/MSCE-POP model

indicates the ability of some PTS to transport to and from the European region.

· PTS often possess very high long-range transport potential and hemispheric/global scale is reasonable

to assess European contamination. The results of EMEP/MSCE-POP model indicate the ability of

some PTS such as PCBs, PCDDs/Fs, -HCH.

5. PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE REGIONAL CAPACITY AND NEED TO MANAGE PTS

Region III has 29 countries, 22 from them signed and 8 already ratified SC. Many countries of the Region also

signed (24 from 36 which signed this Protocol in that time) and ratified (11 from 12) the Aarhus Protocol to the

Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution on POPs.

The production and use of PCBs and OCPs are restricted or banned with very few exceptions. Air, water, soils,

plants and foods are legally protected against hazardous substances in the Region. The PTS inventories of

releases to air, water, land and products are ongoing process. Few countries has complex emission inventory

based on the measurement of real emission factors, all countries based on EMEP and CORINAIR activities are

using the European Atmospheric Emission Guidebook for annual inventory, but lack of actual inventories exist

as far as water and land releases and the products contents of PTS. The most "open" problem is PTS by-

products such as PCDDs/Fs, PAHs, HCB. Also the inventory of obsolete pests is on the acceptable level. The

evidence of PTS hot spots is still problem in CEECs.

Conclusions

· The production and use of PCBs and OCPs are restricted or banned with very few exceptions. Region

has legal, economical and political capacity for solution of PTS environmental problems mainly based

on the EU strategy and co-operation between EU and accession countries.

xiii

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1.

BACKGROUND

The introduction of xenobiotic chemicals that are generally referred to as "persistent toxic substances" (PTS)

into the environment and their resulting effects is a major issue that gives rise to concerns at local, national,

regional and global scales. Many of the substances of greatest concern are organic compounds characterised by

persistence in the environment, resistance to degradation, and acute and chronic toxicity. In addition, many are

subject to atmospheric, aquatic or biological transport over long distances and are thus globally distributed,

detectable even in areas where they have never been used. The lipophilic character of these substances causes

them to be incorporated and accumulated in the tissues of living organisms leading to body burdens that pose

potential risks of adverse health effects. Toxic chemicals, which are less persistent but for which there are

continuous releases resulting in essentially persistent exposure of biota, raise similar concerns. The persistence

and bioaccumulation of PTS may also result in an increase over time of concentrations in consumers at higher

trophic levels, including humans.

A sub-group of the persistent toxic substances are the "persistent organic pollutants" (POPs) identified by the

international community for immediate international action1. These chemicals have serious health and

environmental effects, which may include carcinogenicity, reproductive impairment, developmental and

immune system changes, and endocrine disruption, thus posing a threat of lowered reproductive success and in

extreme cases possible loss of biological diversity.

1.2.

OVERVIEW OF THE RBA PTS PROJECT

Following the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety2, the UNEP Governing

Council decided in February 1997 (Decision 19/13 C) that immediate international action should be initiated to

protect human health and the environment through measures which will reduce and/or eliminate the emissions

and discharges of an initial set of twelve persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Accordingly an

Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established with a mandate to prepare an international

legally binding instrument for implementing international action on certain persistent organic pollutants. To

date three3 sessions of the INC have been held. These series of negotiations have resulted in the adoption of the

Stockholm Convention in 2001. The initial 12 substances fitting these categories that have been selected under

the Stockholm Convention include: aldrin, endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, toxaphene, mirex, heptachlor,

hexachlorobenzene, PCBs, dioxins and furans. Besides these 12, there are many other substances that satisfy

the criteria listed above for which their sources, environmental concentrations and effects are to be assessed.

Persistent toxic substances can be manufactured substances for use in various sectors of industry, pesticides, or

by-products of industrial processes and combustion. To date, their scientific assessment has largely

concentrated on specific local and/or regional environmental and health effects, in particular "hot spots" such as

the Great Lakes region of North America or the Baltic Sea. In response to the long-range atmospheric transport

of PTS, instruments such as the Convention on Long-Range Trans-boundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) under the

auspices of the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) have been developed. The Basel Convention

regulates the trans-boundary movement of hazardous waste, which may include PTS. Some PTS are covered

under the recently adopted Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain

Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade. FAO has initiated a process to identify and

manage the disposal of obsolete stocks of pesticides, including PTS, particularly in developing countries and

countries with economies in transition.

1.2.1. Objectives

There is a need for a scientifically-based assessment of the nature and scale of the threats to the environment

and its resources posed by persistent toxic substances that will provide guidance to the international community

1

The initial twelve POPs are: aldrin, chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor, hexachlorobenzene, mirex, toxaphene,

polychlorinated biphenyls, dioxins and furans.

2

Conclusions of the IFCS sponsored Experts Meeting on POPs and final Report of the ad hoc working group on POPs, Manila, 17-

22 June 1996, "Persistent Organic Pollutants: Considerations for Global Action".

3

At the time of the submission of the project proposal, October 1999.

1

concerning the priorities for future remedial and preventive action. The assessment will lead to the

identification of priorities for intervention, and through application of a root cause analysis will attempt to

identify appropriate measures to control, reduce or eliminate releases of PTS, at national, regional or global

levels (Annex D).

The objective of the project is to deliver a measure of the nature and comparative severity of damage and

threats posed at national, regional and ultimately at global levels by PTS. This will provide the GEF with a

science-based rationale for assigning priorities for action among and between chemical related environmental

issues, and to determine the extent to which differences in priority exist among regions.

1.2.2. Results

The project relies upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and information as the basis for the

assessment. No research will be undertaken to generate primary data, but projections will be made to fill

data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment. The proposed activities are designed to obtain

the following expected results:

1) Identification of major sources of PTS at the regional level;

2) Impact of PTS on the environment and human health;

3) Assessment of trans-boundary transport of PTS;

4) Assessment of the root causes of PTS related problems, and regional capacity to manage these

problems;

5) Identification of regional priority PTS related environmental issues; and

6) Identification of PTS related priority environmental issues at the global level.

The outcome of this project will be a scientific assessment of the threats posed by persistent toxic substances to

the environment and human health. The activities to be undertaken comprise an evaluation of the sources of

persistent toxic substances, their levels in the environment and consequent impact on biota and humans, their

modes of transport over a range of distances, the existing alternatives to their use and remediation options, as

well as the barriers that prevent their good management.

1.3.

METHODOLOGY

1.3.1. Regional divisions

To achieve these results, the globe is divided into 12 regions namely: Arctic, North America, Europe,

Mediterranean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indian Ocean, Central and North East Asia (Western North Pacific), South

East Asia and South Pacific, Pacific Islands, Central America and the Caribbean, Eastern and Western south

America, Antarctica. The twelve regions were selected based on obtaining geographical consistency while

trying to reside within financial constraints.

1.3.2. Management structure

The project is managed by the project manager situated at UNEP Chemicals in Geneva, Switzerland. Each

region is controlled by a regional coordinator assisted by a team of approximately 4 persons. The co-ordinator

and the regional team are responsible for promoting the project, the collection of data at the national level and

to carry out a series of technical and priority setting workshops for analysing the data on PTS on a regional

basis. Besides the 12 POPs from the Stockholm Convention, the regional team selects the chemicals to be

assessed for its region with selection open for review during the various workshops undertaken throughout the

assessment process. Each team writes the regional report for the respective region.

1.3.3. Data processing

Data is collected on sources, environmental concentrations, human and ecological effects through

questionnaires that are filled at the national level. The results from this data collection along with presentations

from regional experts at the technical workshops, are used to develop regional reports on the PTS selected for

analysis. A priority setting workshop with participation from representatives from each country results in

priorities being established regarding the threats and damages of these substances to each region. The

2

information and conclusions derived from the 12 regional reports will be used to develop a global report on the

state of these PTS in the environment.

The project is not intended to generate new information but to rely on existing data and its assessment to arrive

at priorities for these substances. The establishment of a broad and wide- ranging network of participants

involving all sectors of society was used for data collection and subsequent evaluation. Close cooperation with

other intergovernmental organizations such as UNECE, WHO, FAO, UNPD, World Bank and others was

obtained. Most have representatives on the Steering Group Committee that monitors the progress of the project

and critically reviews its implementation. Contributions were garnered from UNEP focal points, UNEP POPs

focal points, national focal points selected by the regional teams, industry, government agencies, research

scientists and NGOs.

1.3.4. Project funding

The project costs approximately US$4.2 million funded mainly by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) with

sponsorship from countries including Australia, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the USA. The

project runs between September, 2000 to April, 2003 with the intention that the reports be presented to the first

meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention projected for 2003/4.

Results from the project will be used by the GEF and other funding agencies to provide priorities for future

remedial action to reduce or eliminate these substances from the environment. In addition, the project will

provide support to international conventions such as the Rotterdam Convention, the UNECE LRTAP

Convention, the Regional Seas Agreement and the Stockholm Convention. It will present opportunities for

bilateral or multilateral action, network building and co-operation within and between regions and stimulate

research through the identification of data gaps.

1.4.

SCOPE OF THE EUROPEAN REGIONAL ASSESSMENT

1.4.1. Introduction

Europe is the largest chemical-producing region in the world, accounting for 38 % of the total; Western Europe

alone accounts for 33 % (UN ECE, 1997; EEA 1998). Chemical production and use provide 2 % of Europe“s

GDP and 7 % of its employment.

The number of existing chemicals on the market is large, but the exact number is unknown. Over 100 000 were

registered in the European Inventory of Existing Commercial Chemical Substances (EINECS) in 1981, but

current estimates of marketed chemicals varies widely, from 20 000 to as many as 70 000. Little is known

about the toxicity of about 75 % of these chemicals. Of the existing chemicals, some have been selected for risk

assessment by various international conventions or bodies. The increasing interest is focused on the chemical

properties of persistent and bioaccumulative chemicals and most of the activities involve the development of

substance risk profiles.

1.4.2. Omissions/weaknesses

The numerous data that have been used to estimate PTS emissions and human exposure levels are only of

limited comparability (Liem and van Zorge, 1995).

Over the last 40 years of continuous determination of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) and polychlorinated

biphenyls (PCBs) in environmental samples, the analytical procedures have been changing according to the

developments in the analysis of trace substances. Unfortunately, comparisons between contemporary analytical

results and older data can be questionable because of differences in the analytical procedures. The authors of

various reports and papers have used different formats for the presentation of their material and often such

important data as the number of samples, date of sampling and limit of detection, have been ommitted(Kocan et

al., 1994a, b; Schutz et al. 1998).

Consequently, some of the data presented in this study should be treated as indicating general levels and trends

in environmental contamination and human exposure to PCBs and certain OCPs. Where possible, trends and

other evaluations given in this report will include qualifying information to allow a better insight into the

validity and comparability of the data.

3

Analytical uncertainty will largely influence the comparisons between the estimated dioxin emissions for the

several countries. However, reported values should be regarded as best available estimates so far (Liem and van

Zorge, 1995).

Based on the published data, no clear indication of substantial differences in dioxin levels of common sources

can be noted. Some differences exist in food consumption patterns between the selected countries and some

differences occur in the selection of foods likely to contribute to the total dioxin intake. Obviously, these

differences are not reflected in the intakes that have been estimated for the different background exposures in

the selected countries.

1.4.3. Other European Assessment projects

A number of regional organisations have already conducted assessments of persistent toxic substances. Where

they exist, the present project will rely on these assessments which include the Quality Status of the North East

Atlantic completed by the Oslo and Paris Commission, the State of the Arctic Environment completed by the

Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, the State of the Marine Environment of the Baltic of the

Helsinki Commission, and the work accomplished in the European Union through the Dangerous Substances

Directive.

1.4.3.1. The Convention on Long-Range Trans-boundary Air Pollution (LRTAP)

In the European region, in addition to EU Directives and regional initiatives, countries, which are members of

EU and newly associated states, are guided by a number of regional and international treaties (EEA, 1998;

HELCOM, 2000; OSPAR, 2000).

Regionally the most important one is The Convention on Long-Range Trans-boundary Air Pollution (LRTAP),

adopted in 1979 under the auspices of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) covers

Europe and North America. This Convention includes measures for eliminating or restricting use, reducing

consumption and unintentional emissions or contamination, eliminating waste and improving the management

of chemicals. The POPs Protocol of this Convention includes 16 pollutants 12, which are on the list of SC

plus chlordecone, hexabromobiphenyl, hexachlorocyclohexanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

Based on the decisions of Steering Body of CLRTAP and WHO Europe, the new evaluation of some POPs

from the list of POPs Protocol and some new candidate substances is developed.

1.4.3.2. OSPAR Convention

The 1992 OSPAR Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic requires

that Contracting Parties shall `take all possible steps to prevent and eliminate pollution and shall take the

necessary measures to protect the maritime area against the adverse effects of human activities so as to

safeguard health and to conserve marine ecosystems and, when practicable, restore marine areas which have

been adversely affected'.

To provide a basis for such measures, Contracting Parties are required to undertake and publish at regular

intervals joint assessments of the quality status of the marine environment and of its development, for the

maritime area covered by the Convention. These assessments should also evaluate the effectiveness of

measures taken or planned for the protection of the marine environment, and identify priorities for action

(Article 6 of and Annex IV to the OSPAR Convention).

1.4.3.3. HELCOM activities with regard to hazardous substances including POPs

The first Helsinki Convention was signed in 1974 by the then seven Baltic coastal states and entered into force

on 3 May 1980. In the light of political changes, and developments in international environmental and maritime

law, a new convention was signed in 1992 by all the states bordering on the Baltic Sea and the European

Community. After ratification the Convention entered into force on 17 January 2000. The Convention covers

the whole of the Baltic Sea area including inland waters as well as the water of the sea itself and the seabed.

Measures are also taken in the whole catchment area of the Baltic Sea to reduce land-based pollution.

The Helsinki Commission adopted in its 19th Meeting (26 March 1998) the HELCOM Recommendation 19/5

concerning the HELCOM Objective with regard to Hazardous Substances. The HELCOM Objective with

regard to hazardous substances is to prevent pollution of the Convention Area by continuously reducing

discharges, emissions and losses of hazardous substances towards the target of their cessation by the year 2020,

4

with the ultimate aim of achieving concentrations in the environment near background values for naturally

occurring substances and close to zero for man-made synthetic substances. Hazardous substances are

substances that are toxic, persistent and liable to bioaccumulate, or otherwise give reason for concern - by

influencing the hormone or immune systems (HELCOM).

1.5.

GENERAL DEFINITIONS OF CHEMICALS

1.5.1. Persistent Toxic Substances

The twelve persistent organic pollutants (POPs) from the Stockholm Convention are separated into three

groups, pesticides, industrial compounds and unintended by-products. One compound belongs to more than one

group, hexachlorobenzene. It belongs to all three groups, pesticides (fungicide), industrial compounds (by-

product) and unintended by-products. The regional specific PTS are also defined. Besides the twelve

substances selected under the Stockholm Convention (aldrin, endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, heptachlor,

mirex, toxaphene, hexachlorobenzene, PCBs, dioxins and furans), the following substances have also been

included in this assessment: atrazine, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, lindane, organic mercury, organic tin,

pentachlorophenol, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, short chain chlorinated paraffins, hexabromobiphenyl,

phthalates, nonylphenols and tert-octylphenol.

1.5.2. Pesticides

1.5.2.1. Aldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-1,4,4a,5,8,8a-hexahydro-1,4-endo,exo-5,8-dimethano-naphthalene

(C12H8Cl6).

CAS Number: 309-00-2

Properties: Solubility in water: 27 µg.l-1 at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 5.17-

7.4.

Discovery/Uses: It has been manufactured commercially since 1950, and used throughout the world up to the

early 1970s to control soil pests such as corn rootworm, wireworms, rice water weevil, and grasshoppers. It has

also been used to protect wooden structures from termites.

Persistence/Fate: Readily metabolized to dieldrin by both plants and animals. Biodegradation is expected to be

slow and it binds strongly to soil particles, and is resistant to leaching into groundwater. Aldrin was classified

as moderately persistent with half-life in soil and surface waters ranging from 20 days to 1.6 years.

Toxicity: Aldrin is toxic to humans; the lethal dose for an adult has been estimated to be about 80 mg.kg-1 body

weight. The acute oral LD50 in laboratory animals is in the range of 33 µg.g-1 body weight for guinea pigs to

320 mg.kg-1 body weight for hamsters. The toxicity of aldrin to aquatic organisms is quite variable, with

aquatic insects being the most sensitive group of invertebrates. The 96-h LC50 values range from 1-200 µg.l-1

for insects, and from 2.2-53 µg.l-1 for fish. The maximum residue limits in food recommended by FAO/WHO

varies from 0.006 mg.kg-1 milk fat to 0.2 mg.kg-1 meat fat. Water quality criteria between 0.1 to 180 µg.l-1 have

been published.

1.5.2.2. Chlordane