UNEP - GEF

Regionally

3

Based

Assessment

of

Persistent

Toxic Substances

Global R

UNEP Chemicals

11-13 Chemin des Anémones

eport 200

CH-1219 Châtelaine

Geneva, Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 917 1234

Fax: +41 22 797 3460

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

eport 200

3

R

http://www.chem.unep.ch/pts

UNITED NA

TIONS

Designed and printed by the Publishing Service, United Nations, Geneva -- GE.03.01710 -- July 2003 -- 2,000

Global

This report was financed by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through a global project with co-

financing from the Governments of Australia, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States of

America.

This publication is produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound

Management of Chemicals (IOMC).

This publication is intended to serve as a guide. While the information provided is believed to be

accurate, UNEP disclaim any responsibility for the possible inaccuracies or omissions and

consequences, which may flow from them. Neither UNEP nor any individual involved in the

preparation of this report shall be liable for any injury, loss, damage or prejudice of any kind that may

be caused by any persons who have acted based on their understanding of the information contained

in this publication.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations of UNEP

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the

delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), was

established in 1995 by UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO and OECD (Participating Organizations),

following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and

Development to strengthen cooperation and increase coordination in the field of chemical

safety. In January 1998, UNITAR formally joined the IOMC as a Participating Organization. The

purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and activities pursued by the

Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the sound management of

chemicals in relation to human health and the environment.

Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested

together with a reference to the document. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint

should be sent to UNEP Chemicals.

UNEP

CHEMICALS

UNEP Chemicals11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 917 8170

Fax:

+41 22 797 3460

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and Economics Division

Regionally

Based

Assessment

of

Persistent

Toxic Substances

CONTENTS

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

Abbreviations and acronyms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4

eport 2003

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Source Characterization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Environmental Levels, Trends and Effects . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Assessment of Major Transport Pathways . . . . . . . . . . . 137

Root Causes, Needs, Barriers and Alternatives to PTS . 160

Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185

Basic Chemical Definitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204

Global R

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

Funding:

Funding for this assessment was provided by The Global Environmental Facility, the governments of Australia, Canada,

France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States of America.

Management:

Project Directors James Willis, Ahmed Djoghlaf

Project Manager Paul Whylie

Steering Group - The World Health Organisation, The World Bank, International PPOs Elimination Network,

UNEP/GEF Coordination Unit, International Council of Chemical Associations, The Scientific and Technical Advisory

Panel of the GEF, The United Nations Environment Programme Global Resource Information Database, The Global

International Waters Assessment, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, United Nations Environment

Programme - Chemicals Division

Scientific Technical Support Bo Wahlstrom, Heidi Fiedler, Laurent Granier

Administrative Support Cairine Cameron, Immaculate Njeru, Esther Santana

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors of the Global Report:

Paul Whylie UNEP, Chemicals Division

Patrick Dyke United Kingdom

Joan Albaiges Spain

Frank Wania Canada

Ricardo Barra Chile

Ming Wong Hong Kong, People's Republic of China

Henk Bouwman South Africa

Authors of the Regional Reports:

Arctic Region: Institution The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, Oslo Norway.

Author: Hans Martin.

North America Region: Institution North America Commission for Environmental Cooperation, Montreal Canada.

Regional Coordination: Victor Shantora and Joanne O'Reilly.

Authors: Hans Martin, Jorge Sanchez, Roy Hickman, Tony Clarke, Stephanie Martin, Padro Colucci.

Europe Region: Institution Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic.

Authors: Ivan Holoubek, Ruth Alcock, Eva Brorström-Lunden, Anton Kocan, Valeryj Petrosjan, Ott Roots, Victor

Shatalov

Mediterranean Region: Institution Associació per el Desenvolupament de la Ciència i la Technologia, Barcelona,

Spain.

Authors: Joan Albaiges, Fouad Abousamra, Elena De Felip, Mladen Picer, Assem Barakat, Jean-François Narbonne.

Sub-Saharan Africa Region: Institution University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Authors: Oladele Osibanjo, Nabil Bashir, Hosseah Onyoyo, Henk Bouwman, Robert Choong Kvet Yive, Jose

Okond'Ahoka.

Indian Ocean Region: Institution Industrial Toxicology Research Centre, Lucknow, India.

Authors: P.K. Seth, M.U. Beg, M. Yousaf Hayat Khan, G.K. Manuweera, M. Sengupta.

Central & N.E. Asia Region: Institution Hong Kong Baptist University, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong SAR.

Authors: Ming Wong, Kyunghee Choi, Elena Grosheva, Shin-ichi Sakai, Yasuyuki Shibata, Noriyuki Suzuki, Wang Ji.

S.E. Asia & S. Pacific Region: Institution The Marine Environment and Resources Foundation Inc.

Authors: Gil S. Jacinto, Des W. Connell, Sani Ibrahim, Lim Kew Leong.

Pacific Islands Region: Institution: South Pacific Regional Environment Programme, Apia, Samoa.

Authors: Bruce Graham, Bill Aalbersberg, Michelle Rogow, Pita Taufatofua.

Central America & the Caribbean Region: Institution Secretaria Permanente del Consejo Superior Universitario

Centroamericano.

Authors: Luisa Castillo, Roosebelt Gonzalez, Joth Singh, Oscar Nieto, Gonzalo Dierksmeier, Jaime Espinoza.

E & W South America Region: Institution EULA-Chile Center, University of Concepción, Concepción, Chile.

Authors: Ricardo Barra, Juan Carlos Colombo, Wilson Jardim, Nadia Gamboa, Gabriela Eguren.

Antarctica Region: Institution Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, Cambridge, UK.

Author: Julian Priddle.

Special Contributions:

The software to capture the data was developed by Kisters AG, Duisburg, Germany.

The cover page design was developed by Sylvie Sahuc, UNOG Printing Services, Geneva, Switzerland.

The participants of the Global Priority Setting Meeting gave meaningful review to the draft global report.

2

PREFACE

The Global Environment Facility through its Contaminated Based Operational Programme (OP10) supports

projects that can lead to implementation of more comprehensive approaches for restoring and protecting the

International Waters environment. The Programme assists initiatives that help characterise the nature, extent

and significance of these contaminants. In furthering this process, UNEP, with the generous financial

support of the Global Environment Facility Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and

the United States of America undertook this regionally based assessment of persistent toxic substances

(PTS). A major objective was to identify priorities for future interventions by the GEF under OP10.

Additionally, the assessment will greatly assist the GEF in shaping the strategic priorities of its third phase.

The project achieves this by:

Delivering a measure of the nature and comparative severity of damage and threats posed at national,

regional and ultimately at global levels by PTS.

Providing the GEF, UNEP and others with a science-based rationale for assigning priorities for action

among and between chemical-related environmental issues and for determining the extent to which

differences in priority exist among regions.

Evaluating the sources of PTS, their levels in the environment and consequent impacts on biota and

humans, their modes of transport over a range of distances, the existing alternatives to their use and

remediation options, the global capacity for their good management and the barriers that prevent such

management.

Stimulating research through the identification of data gaps.

This report is based upon the information presented in the twelve regional reports developed during the

regional phase of the project. The project was managed by UNEP Chemicals in Geneva, Switzerland.

UNEP would like to thank the Steering Group members that met periodically and provided thoughtful and

meaningful direction during the implementation of the project.

Many scientists, representatives of governments, industry and non-government organisations and other

interested parties participated in providing data, and in the technical and priority setting meetings that were

held across all relevant regions. Unfortunately, we cannot list all the persons but offer our thanks and

appreciation to their contribution and effort in the development of the regional and global reports. The lead

authors for this report deserve special mention for overcoming the challenge of drafting and finalising the

document. Their task was a difficult one given the mountains of data that required sorting and analysis. We

thank them for their patience, wisdom and steadfast commitment toward the successful completion of this

report.

This global assessment of PTS is the first of its kind. The many major data gaps that were encountered and

the short time period allowed provided many challenges. However, we are pleased to present the initial

Regionally Based Assessment of PTS and hope it will be useful to governments, non-governmental

organizations, intergovernmental organizations and others in their efforts to protect people and the

environment from the risks of toxic chemicals.

Since this project was initiated, governments negotiated and adopted the Stockholm Convention on Persistent

Organic Pollutants. We hope that this assessment will be a useful contribution to the work of the Parties of

that treaty in protecting our health and environment, and will also support efforts under other international

agreements such as the Rotterdam Convention, the Basel Convention, the UNECE LRTAP Convention, the

Global Programme of Action for Protection of the Marine Environment and the Regional Seas Agreements.

Klaus Töpfer

Executive Director

United Nations Environment Programme

3

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ACP

Arctic Contamination Potential

ADI

Acceptable

Daily

Intake

ALRT

Atmospheric Long Range Transport

AMAP

Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme

APEs

Alkylphenol

Ethoxylates

BCF

Bioconcentration

Factor

BHC

Benzenehexachloride

BPH

Benzo(a)pyrene oxidation

CEEC

Central and Eastern Europe

CEP

Caspian Environment Programme

CIS

Commonwealth of Independent States

CSIRO

Commonwealth Scientific & Industrial Research Organisation

CTD

Characteristic Travel Distance

DDD /DDE

Metabolites of DDT

DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

DLPCBs

Dioxin-like PCBs

EDCs

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

EMAN

Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Network

EMEP

Co-operative Programme for Monitoring and Evaluation of the Long-Range

Transmission of Air Pollutants in Europe

EPER

European Pollutant Emission Register

ERL

Effects Range Low

ERM

Effects Range Median

EROD

7-ethoxyresorufin-O-deethylase

EUSES

European Union System for the Evaluation of Substances

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations

FERTIMEX Fertilizantes

Mexicianos,

S.A.

GEF

Global Environment Facility

GEMS

Global Environment Monitoring System

GLBTS

Great Lakes Bi-national Toxics Strategy

HCB

Hexachlorobenzene

HELCOM

Helsinki Commission/The Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission

HCHs

Hexachlorocyclohexanes

HIPS

High Impact Polystyrene

HYSPLIT

Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory

HxBB

Hexabromobiphenyl

4

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

IFCS

Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety

IMO

International

Maritime

Organisation

INFOCAP Information

Exchange

Network on Capacity Building for the Sound Management of

Chemicals

IPPC

Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control

I-TEQ

International Toxicity Equivalence

KAW

Air/Water Partition Coefficient

KOA

Octanol/Air Partition Coefficient

Kow

Octanol/Water Partition Coefficient

LC50 Median Lethal Concentration

LD50 Median Lethal Dose

LOAEL

Lowest Observable Adverse Effect Level

LRT

Long

Range

Transport

LRTAP

Long Range Transport Air Pollutants

LRTP

Long Range Transport Potential

MDL

Minimum

Detectable

Level

MEDPOL

Mediterranean Pollution Monitoring and Research Programme

MEA

Multi Lateral Environmental Agreements

MEMAC

Marine Emergency Mutual Aid Centre

MRL

Maximum Residue Limit

MSCE-East

Meteorological Synthesizing Centre-East

MSWI

Municipal Solid Waste Incinerator

NAFTA

North American Free Trade Agreement

NARAPs

North American Regional Action Plans

ND

Not

detected

NEPC

National Environment Protection Council

NGOs

Non-Governmental Organisations

NHATS

National Human Adipose Tissue Survey

NIS

Newly Independent States

NOAA

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NOAEL

No Observable Adverse Effect Level

NOEL

No Observable Effect Level

NPRI

National Pollutant Release Inventory

NWT

Northwest

Territories

OCs

Organochlorines

OCPs

Organochlorine

Pesticides

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

5

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

OPs

Organophosphates

OSPAR

Commission for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic

PAHs

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

PBDEs

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers

PCBs

Polychlorinated

biphenyls

PCDDs

Polychlorinated dibenzo- p-dioxins

PCDFs

Polychlorinated dibenzofurans

PCP

Pentachlorophenol

PFOS

Perfluorooctane

sulfonate

PIC

Prior Informed Consent

POPs

Persistent Organic Pollutants (group of twelve as defined in the Stockholm Convention

2001)

PRTRs

Pollutant Release and Transfer Registers

PVC

Polyvinylchloride

REACH

Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of Chemicals

RENPAP

Regional Network on Pesticide Production in Asia and Pacific

ROPME

Regional Organisation for the Protection of the Marine Environment

ROWA

Regional Organisation of West Asia

SAICM

Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management

SCCPs

Short-chain chlorinated paraffins

SMOC

Sound Management of Chemicals

SPM

Suspended

particulate

matter

SPREP

South Pacific Regional Environment Programme

SR

Special

Range

t Tonnes

TBBPA

Tetrabromobisphenol A

TCDD

Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

TEL

Tetraethyllead

TEQ

Toxicity

Equivalents

TML

Tetramethyllead

TOMPS

Toxic Organic Micropollutants Survey

TPT

Triphenyltin

TRI

Toxics Release Inventory

UNECE

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

UNIDO

United Nations Industrial Development Organisation

WFD

Water Framework Directive

WHO

World Heath Organisation

WMO

World Meteorological Organization

6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In 1997 the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Governing Council decided that immediate

international action should be initiated to protect human health and the environment through measures which

will reduce and/or eliminate the emissions and discharges of an initial set of twelve "persistent organic

pollutants" (POPs). The present project was initiated in mid-1998 at a time when the negotiations for an

international legally binding instrument for implementing international action on certain persistent organic

pollutants had just started and while the outcome of the negotiations was still purely conjectural. It was

initiated by GEF after discussions with UNEP to address a broader set of issues and substances than those

which finally were agreed under the Stockholm Convention on POPs. This project therefore deals with

"persistent toxic substances" or PTS and is deliberately looking at a wider group of chemicals than the

twelve "POPs" under the Stockholm Convention.

The Regionally Based Assessment of Persistent Toxic Substances (RBA PTS) Project was designed to gather

data and assess the sources, environmental concentrations, the transboundary movement and effects of a

selected number of PTS. The objective of the project is to provide a measure of the threats and damage to

the environment and human health posed by these substances. It is intended that the results of the project

will guide the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and other funding agencies toward priorities for future

action to mitigate the effects of these PTS.

The project was designed to be based in the regions and draw on the resources and expertise at the country

level. Regional teams were set up to be responsible for delivering the data gathering and assessment and

UNEP provided central project management and coordination functions. A steering group made up of

representatives of interested international organisations, environmental and industrial non-governmental

organisations and scientists provided assistance to the project manager in guiding and delivering the project.

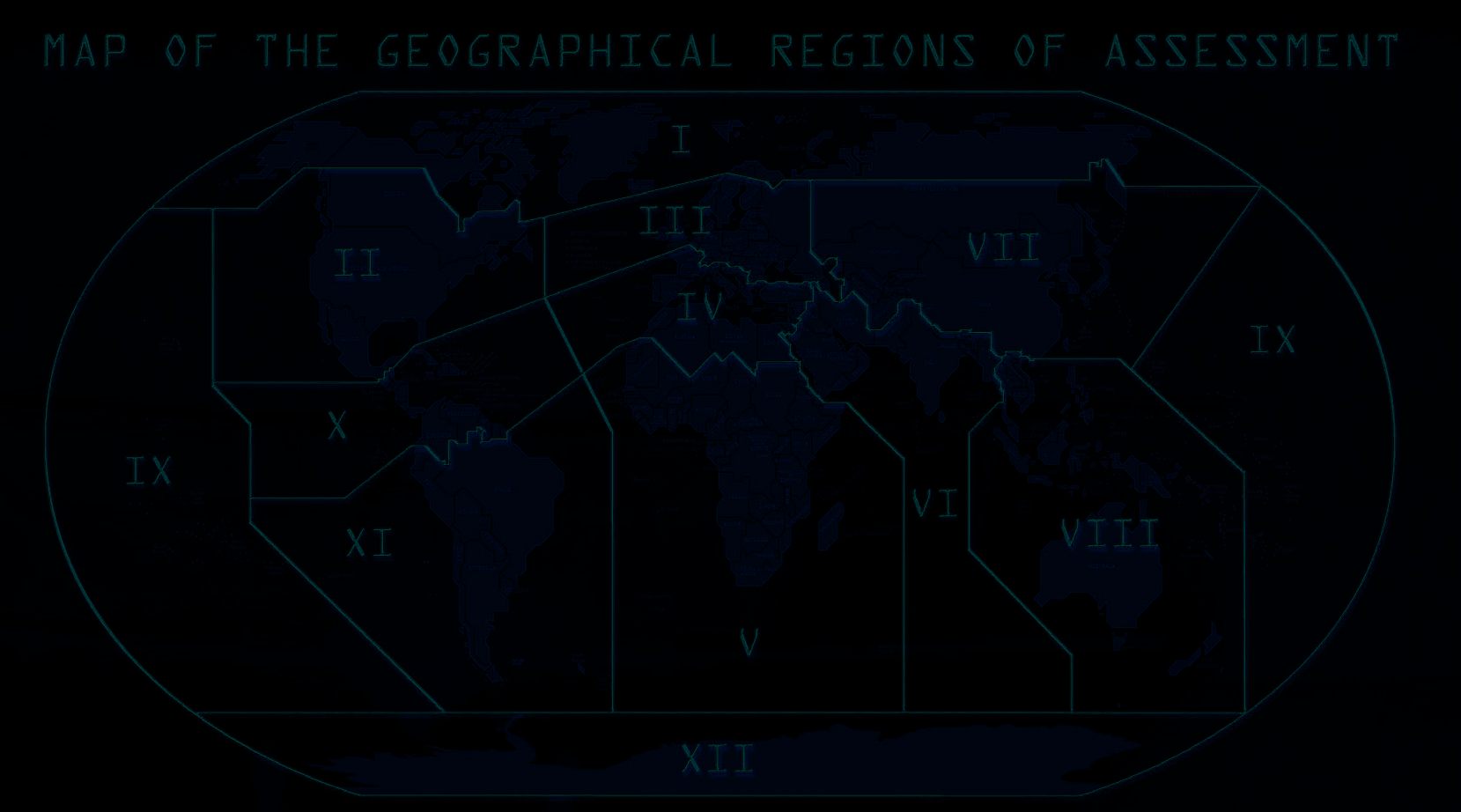

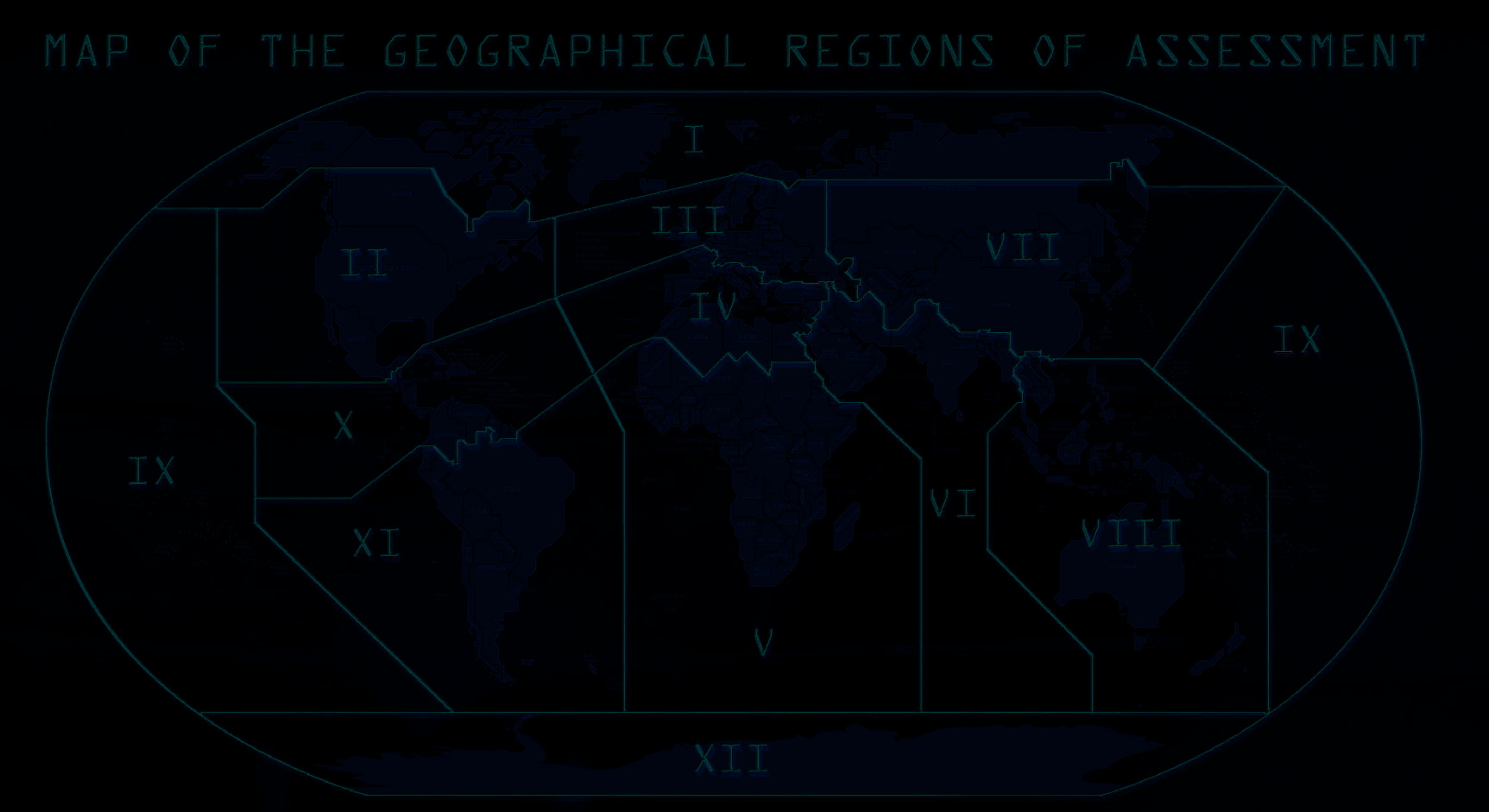

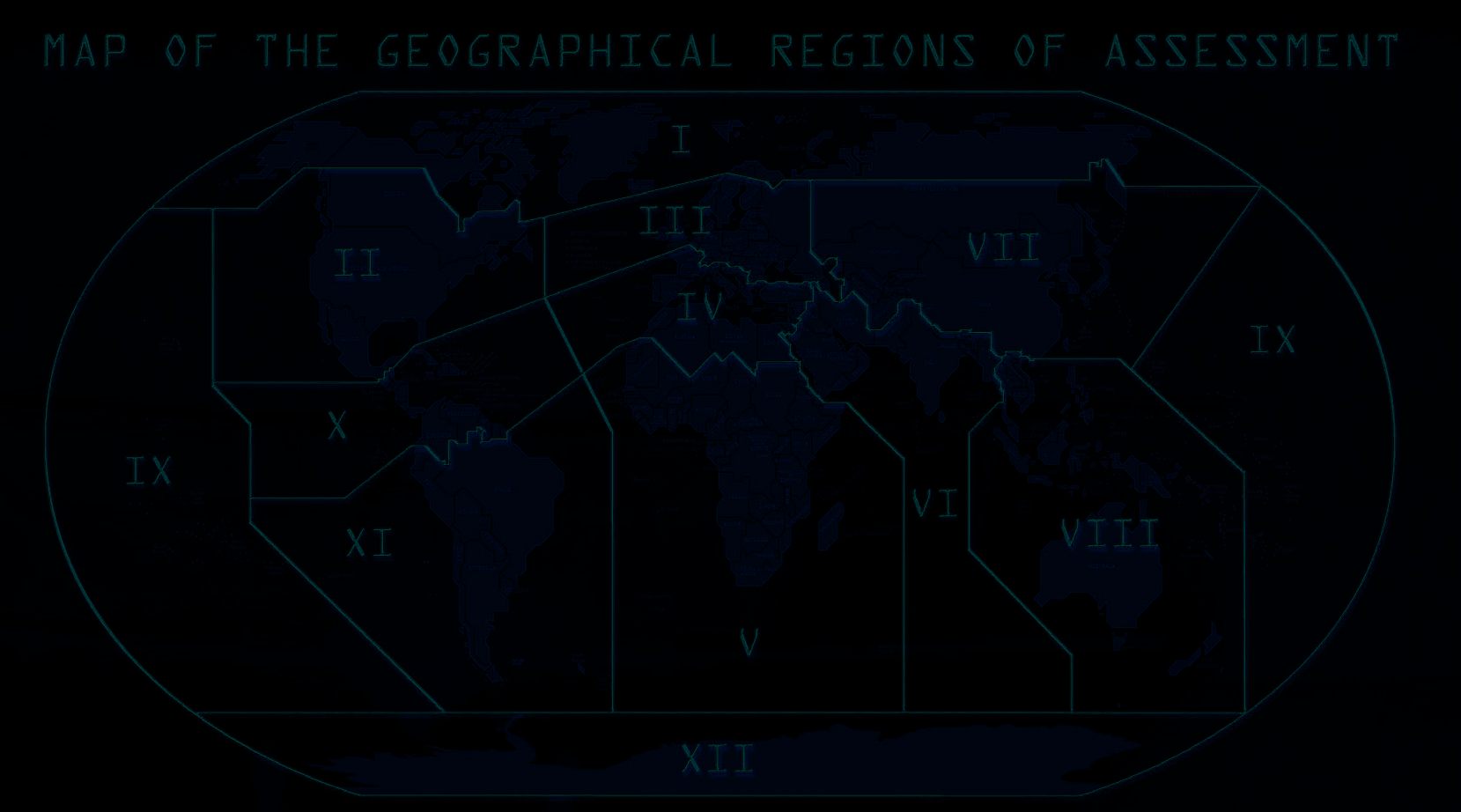

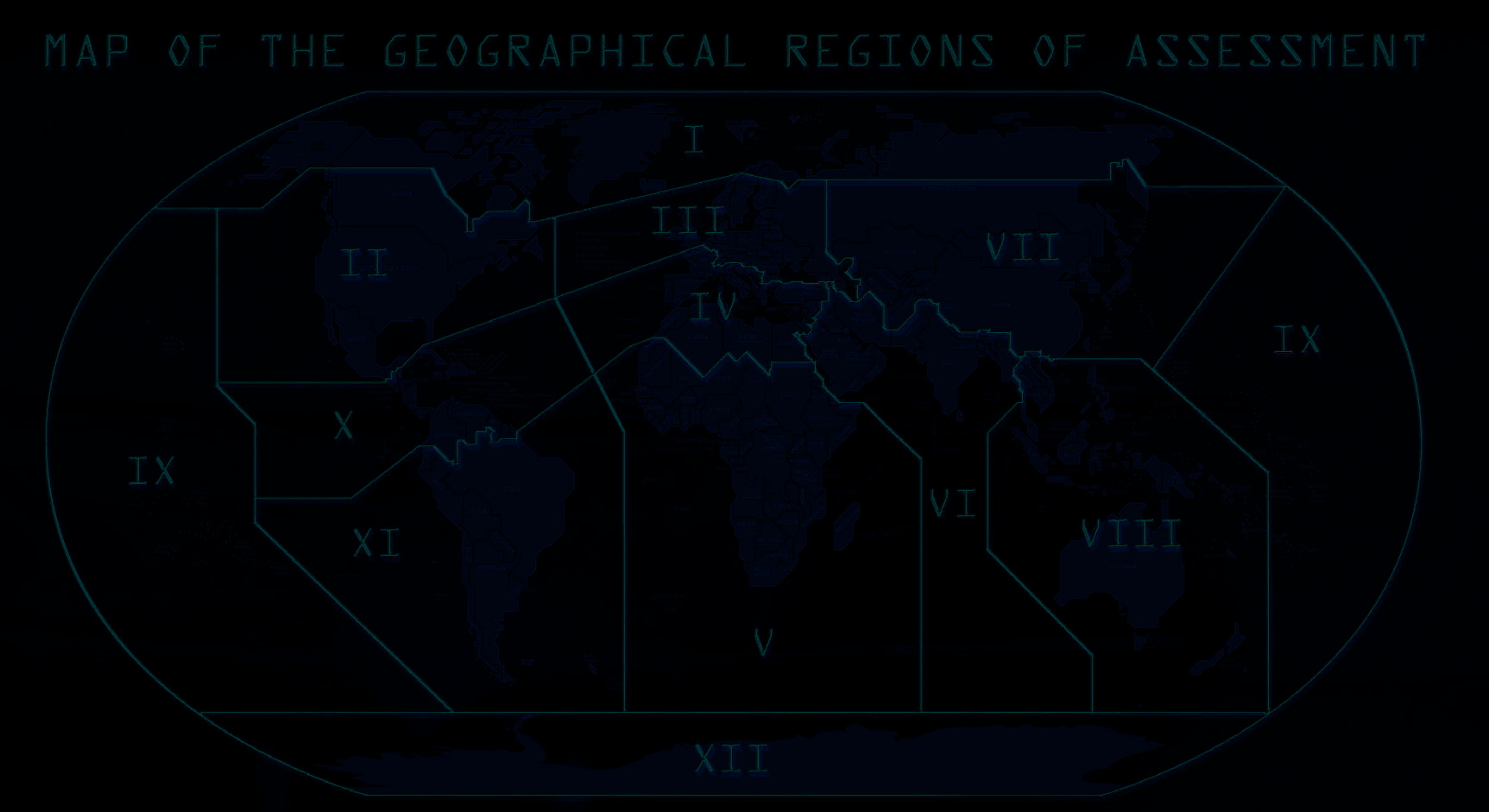

For this project the globe was partitioned into twelve regions. The regions were linked to important

international waters in keeping with the focus of the project. The twelve regions were:

I Arctic

VII - Central and North East Asia

II - North America

VIII - South East Asia and South Pacific

III Europe

IX - Pacific Islands

IV Mediterranean

X - Central America and the Caribbean

V - Sub-Saharan Africa

XI - Eastern and Western South America

VI - Indian Ocean

XII - Antarctica

7

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

Methodology

As this was a regionally based assessment, most of the work occurred in the various regions and effectively

at the country level. A key feature of the data gathering part of the project was that an invitation was

extended very widely for data. Information was sought from governments, research institutions, academics,

non-governmental groups and industry. A Regional Coordinator and an accompanying team of four to five

persons were selected. The process for the assessment is explained in the box below.

Steering

UNEP

Group

Chemicals

Project

Manager

Regional Teams

Data Collection

Regional Technical Workshops

Regional Priority Setting Meetings

12 Regional Reports

Global Priority Setting Meeting

A Global Report

The regional teams were responsible for data gathering and assembly. One tool that was developed to assist

in this data gathering was a standard data input form or questionnaire. It was clear that when dealing with

complex and disparate data from a wide variety of sources, there is no simple and effective system which will

easily and adequately handle the information.

Technical workshops were held with wide participation of experts within each region. Regional Priority

Setting Meetings were organised in which participants agreed on the key priorities related to PTS amongst

the stakeholders. A Global Team of six experts, along with the Project Manager, was composed to develop

the global report mainly from the findings of the regional reports. A Global Priority Setting Meeting allowed

feedback and further input via comments and submissions into the draft report.

Chemicals assessed

The term `PTS' does not imply any particular level of risk but rather is a broad consideration for substances

that persist in the environment, are found in areas far removed from sources and display some level of

toxicity. Persistent toxic substances may be manufactured intentionally for use in various sectors of industry,

one important sub-group being pesticides, while others may be formed as by-products during a variety of

processes (industrial, non-industrial and natural) including combustion.

All regions considered the 12 designated "Stockholm POP" chemicals. They were also able to select

additional chemicals that were of concern within the region. This project was primarily concerned with data

gathering and not with assessing which chemicals are or could be considered PTS and the inclusion of a

chemical for assessment does not imply that it meets any particular criteria of toxicity, persistence or effect.

Additionally, the assessment of any given chemical in this project does not imply in any way that the

chemical should be subject to inclusion in the list of Stockholm POPs.

The chemicals considered under the project are listed below. Not all the other chemicals were necessarily

assessed by every region during the regional assessment.

8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

List of chemicals assessed

STOCKHOLM POPS

OTHER CHEMICALS

ALDRIN HEXACHLOROHEXANE

ENDRIN POLYAROMATIC

HYDROCARBONS

DIELDRIN ENDOSULPHAN

CHLORDANE PENTACHLOROPHENOL

DDT

ORGANIC MERCURY COMPOUNDS

HEPTACHLOR ORGANIC

TIN

COMPOUNDS

TOXAPHENE ORGANIC

LEAD

COMPOUNDS

MIREX PHTHALATES

HEXACHLOROBENZENE PBDEs

POLYCHLORINATED BIPHENYLS

CHLORDECONE

DIOXINS (PCDDs)

OCTYLPHENOLS

FURANS (PCDFs)

NONYLPHENOLS

ATRAZINE

SHORT-CHAIN CHLORINATED PARAFFINS

PFOS

HEXABROMOBIPHENYL

Conclusions

Many PTS are a historical problem, i.e., their massive and worldwide use occurred during a time of

ignorance of the environmental problems potentially caused by them. In addition, the extensive

commercialisation and industrialisation that was undertaken some fifty years ago, increased the demand and

pace for the production of chemicals and the development of poor processes even in waste management.

The root causes discerned for the expression of PTS are outlined below:

Persistence

Cost of chemicals

Low water solubility

Perceived effectiveness

High toxicity

Ignorance

Unsustainable production/consumption

The capacity to monitor PTS differs widely across regions. While undertaking sophisticated monitoring

programmes and having adequate legislative action to enforce environmental protection, the developed

regions still require further financial resources and increased monitoring facilities. However, the gap is wide

with regards to the needs of the developing regions. In Sub-Saharan Africa, Central America and the

9

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

Caribbean, the Indian Ocean and parts of Asia, the monitoring of PTS is mainly ad hoc and relies on analyses

from research and on accidents. There is need for practical technology transfer and an increase in available

financial resources to provide sustainable development of control mechanisms. Regional partnerships

between developed and developing countries and among the latter should be encouraged.

Barriers do exist that mitigate against the implementation to solutions and alternatives to PTS. These

include the following:

· Lack of comprehensive scientific data

· Lack of monitoring and inventory capacity

· Lack of suitable legislative framework

· Ineffective enforcement of regulations

· Illegal trade and use

· Inappropriate use and abuse

· Lack of awareness and information

· Commercial pressures

· Lack of clear responsibilities and limited coordination

· Lack of financial resources

· Lack of availability and acceptance of alternatives

While many alternatives to PTS have been researched, it is not necessarily easy to find suitable, workable

systems to replace the desired qualities of these chemicals. The quality of persistence, low water solubility

toxicity and the cost efficiency of processes that may release or emit PTS are difficult to replace. However,

there are real examples that do exist where alternative measures have been instituted and have generated the

desired result that was provided by the replaced PTS. Examples include:

For pesticides Integrated Pest Management; Integrated Vector Management; Replacement of chlorinated

pesticides; Organic farming.

For industrial chemicals and unintended by-products Environmentally sustainable production; Best

available technology; Destructive technology without unwanted emissions.

Priority Environmental Source Issues

A lack of data was a serious constraint with the compilation of many of the regional reports, especially from

regions with developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Quantitative comparisons of

production and releases by source type and chemical across regions was very difficult, as the lack of data,

method of reporting, completeness, reported time trends in reductions and or increases, allowed mostly

qualitative horizontal comparisons.

The general and comparative sensitivity of specific regions was not considered (i.e. would a small source of

PAH in Region I be more important, than a relatively large source in a region just to the south?). Key

observations, considerations, conclusions and suggestions that follow are outlined below:

· Obsolete stocks and reservoirs of released PTS (such as contaminated sediments and soils, and stocks of

obsolete pesticides) are located in a number of regions and are major current sources. This aspect has

been identified as a serious concern in developing as well as developed regions, thereby sharing a

common environmental issue. This presents a potential of collaboration on remediation and other

technologies between developed and developing nations, including nations with economies in transition.

· Even though much has been done to reduce emissions, industrial activity, (both in developed and

developing regions as well as countries with economies in transition) must still be considered as a major

source of PCDD/PCDF, and probably other related PTS. The characterisation and location of these

activities on a global basis needs to be better understood, for a strategic application of interventions to be

cost and time effective.

10

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

· Open burning and biomass burning are probable, but largely unknown sources of PAH and PCDD/PCDF

in developing regions, or regions with a mixed economy. Open burning and biomass burning in many

areas exposes biota and human populations, due to their close proximity (land fills, domestic heating,

close location to water etc), and needs to be much better understood. Large cities as such can also be

considered as a concentration of both various PTS sources and exposure routes, specifically involving the

human population. Large cities are normally also located close to fresh water, and often with coastal

areas, two areas of major concern due to pollution potential and sensitivity of the ecosystems.

· The developed regions can be considered as the major sources of intentionally produced industrial PTS

(chlorinated paraffins, PBDE, PFOS and others). This is then transported via the environment, as well as

through trade, to other regions. A better understanding is needed, as double counting (produced in one

country, and used in another) could give the false impression about specific chemicals. The issue of

secondary sources, such as e-waste, also needs to be better understood, as production, transport, primary

use, and waste treatment (secondary use), will all be potential sources (to a greater or lesser extent).

· Very little is still known about the sources of organometalics in all the regions, although mercury is being

addressed by the Global Mercury Assessment. Not enough information was available to make any

qualitative statements about this issue, but concern is still obvious from the various regional reports.

· PCB remains a large problem in almost all the regions, although it should be recognised that PCB is one

of the specific issues that will be addressed by the National Implementation Plans under the Stockholm

Convention.

· DDT and the lack of a clear and effective alternative continue to hamper development, as well affecting

the health of millions of people in many regions. Combined and continued efforts (such as with the

WHO) is needed to address this insidious issue, as well as to raise the understanding of the problems in

other regions.

· The source profile (Table 2.9) indicates that much more is known about most PTS sources in the

developed regions, but in developing regions, major data gaps exist regarding the non-intentional and

intentionally produced industrial PTS. Capacity and means to address the related issues remain a primary

aspect that will need attention to assist developing regions in this regard.

· It must be recognised that the source profile is likely to change with more information from various

activities, including the NIPs. Part of the lack of information can be ascribed to little capacity within

developing regions to address source aspects. It will therefore be very useful if the source profile could

be regularly updated, providing a clear means to understand the global issues, as well as to provide

guidance on interventions, research and prioritisation.

· The source profile is also likely to change, as changes in sources within the various regions, through

mitigation measures or through economic and social development are likely to occur.

· Perhaps one of the most useful outcomes of the Global Source Characterisation was the beginning of the

relative understanding of the contributions and problems faced by the various regions. If the

enhancement of this understanding can be done through the maintenance and expansion of some of the

momentum and networks that has been generated through this effort, much value will be derived on a

number of levels, inter alia research, capacity building, intervention planning and public trust.

The majority of the issues identified above, are in most cases regional specific. This means that addressing

these priorities within the identified regions, will contribute significantly towards reducing the releases on a

global scale. Addressing the issues on a regional level, within the scope of a global strategy, will enable

better application of resources on mitigation measures, sustainable development, environmental protection

and, human health improvement. Future developments however, could change the pattern. Increased

industrialisation of developing regions could alter the global source profile, if appropriate technologies are

not instituted.

Priority environmental concentration issues

As expected, the situation is very different across the regions. There are regions with a tradition in gathering

information on PTS since the 70's, whereas in others there are important data gaps or even no information

exists for some PTS. Therefore, priorities across regions may be based on facts (existing information and

11

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

reported hot spots) or suspicions that environmental levels are high due to the existence of a variety of

sources. From the regional reports the following picture of concerns can be obtained:

· The levels of PTS pesticide chemicals that were widely used across the regions in the past are now

declining because regulatory measures, such as banning, use restrictions, etc. This is the case of DDT,

heptachlor and chlordane. The use of mirex and toxaphene, which has been limited to certain regions,

follow the same trends. These are in general PTS of secondary concern, except in the Polar Regions

where there is evidence of still increasing levels.

· PTS pesticide chemicals that are still in use show detectable levels in practically all environmental

compartments and, in some cases, are quite high. Even when they are banned in some regions there are

also examples of elevated environmental levels in recent records, demonstrating illegal use or transport

between regions. Examples include lindane and endosulphan.

· Industrial PTS chemicals which have been banned or subject to control in some regions (and

environmental levels shows a clear decline since regulatory measures were taken), may still continue to

be used in developing countries, where levels are even increasing as is the case of PCBs. Effective

assessment, control of use and remediation will be a priority.

· Unintentionally produced PTS are of concern in the developed world, where levels reported are high, and

obviously of great concern. Data are scarce in the developing world, representing a big data gap,

although open burning may be of high concern. This is particularly the case with PCDD/PCDFs and

PAHs.

· New candidate chemicals for global concern are insufficiently covered to draw a complete picture, while

there are clear evidences of ecotoxicological effects for some of them. Gathering information becomes a

priority. This is the case of PCP, brominated compounds, alkylphenols, etc.

For a better assessment of the PTS levels and effects, two major gaps need to be adequately filled, and this

becomes also a priority:

Data generation and gathering should be extended throughout the regions, particularly for some PTS and

compartments, and more important, in a harmonised manner, to allow data to be compared over time and

between studies, countries and regions.

Regionally adapted benchmarks, namely environmental quality guidelines and human tolerable daily intakes,

should be defined and more widely used to compare measures of environmental levels with environmental or

health effects.

Integration of information on environmental measurements of sources and pathways with physical and

biological models is required to aid the design and implementation of monitoring, research, and management,

including mitigation.

Recommendations

While many recommendations were made in reports at the regional level, an attempt has been made to

extract considerations that can be translated to achieving a global strategy. It is expected that any future

actions that would consider the data from these reports will ensure that only validated information is captured

in the decision process. Some positive considerations which developed during the implementation of this

project should be incorporated into any relevant post project exercise.

Network The use of the network established should be incorporated into any relevant post project

enterprise. A good relationship exists among all the regional coordinators and teams that will provide

synergy for any future project.

Regional Direction - The use of a regional strategy to attain global results has proven successful for the

implementation of this project. This pattern should be replicated for future initiatives.

Emerging Chemicals - It will be appropriate for UNEP to concentrate on work associated with the twelve

selected PTS under the Stockholm Convention. However, certain other emerging chemicals are a cause for

concern globally and these should be considered in future programmes.

The Stockholm Convention has legally binding obligations for the Parties. These obligations consider the

activities required to address the reduction and control of the selected twelve chemicals under the

12

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Convention. This report recognises the ultimate responsibility of the Parties to the Stockholm Convention,

and presents certain recommendations on the Stockholm POPs for possible consideration at the Conference

of the Parties. These include:

o Ratification of Environmental International Conventions The three major International

Conventions pertaining to chemical management (Stockholm, Rotterdam and Basel) present a

unique opportunity for all countries to be involved regionally and internationally in chemical

management exercises that can only enhance the reduction of the levels and effects of PTS in the

environment. In particular, the ratification of the Stockholm that directly considers the reduction

and ultimate elimination of twelve POPs should be considered with priority.

o Global strategy for Implementation of NIPs All countries that have signed the Stockholm

Convention that are considered `GEF eligible' have access to funds to create National

Implementation Plans (NIPs) under the Stockholm Convention. These Plans are being

administered by several Executing International Agencies. Even though there are disparities

between countries, it is recommended that a global strategy be crafted to ensure efficiency, foster

synergy between Agencies and to promote regional collaboration during the development of

NIPs

o A global assessment of the strategies to eliminate the use of DDT for malaria

control - Many countries are now battling to reduce if not eliminate the use of DDT for malaria

vector control. A global assessment would include a close collaboration with industry and the

WHO should recommend the best alternatives that now exist. The assessment would be used to

promote the development of alternatives and to pursue the use of other less caustic chemicals and

non-chemical solutions.

Below are post project initiatives suggested for future action based on the results of the assessment. These

initiatives involve, in the main, chemicals outside of the twelve selected Stockholm POPs.

Update of the Regionally Based Assessment of PTS

Many pieces of data and aggregated analyses were not captured under the current assessment. As such, it is

considered prudent that the assessment be updated on a regular basis. This exercise could be carried out

every 3-5 years resulting in a periodic assessment of the status of the selected chemicals with room for

possible addition or subtraction.

Filling of data gaps

Consistently throughout the regional reports, it was established that major data gaps existed that prevented

the scientific acknowledgement of intuitive concerns for certain chemicals. These gaps varied from region to

region and from chemical to chemical. Unfortunately, it is difficult to prioritise the importance of these data

gaps on a global scale given the differences between regions. However, an effort to glean information based

on regional priorities should be considered with expediency.

Conduct of a global assessment of PCDD/PCDFs and PAHs emissions from

open burning

It is being shown from the RBA PTS that open burning is a major concern in all habitable regions under the

project. However, there is limited knowledge of the extent of the problem. The NIPs being developed by

each signatory to the Stockholm Convention includes an assessment of the needs associated with the

reduction of emissions of dioxins and furans. However, this could be aided by a global programme to

ascertain measurements for various open burning sites. The intention is to establish with a fair degree of

accuracy, estimated emissions from these various sources using models based on representative

measurements taken from major, established open burning sites.

A resource centre for new PTS chemicals

In order to be at the cutting-edge of the emerging concerns from certain PTS, UNEP Chemicals will develop

a resource centre for those chemicals for which limited information is available especially in the developing

world. These substances will include all the emerging chemicals identified in this report outside of the

13

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

Stockholm POPs. The centre would be interactive and developed as a network with a clearinghouse

function. Such a centre would collate data from the developed and developing world, collaborate in ongoing

work analysing these chemicals in terms of production, use and environmental concentrations and provide

publications to share the emerging information in a wide circulation throughout all countries.

A global strategy for increasing public awareness on PTS issues

Consistently, the recurring message in the recommendations for all the regional reports is the need for broad

public awareness programmes especially among civil society to increase the knowledge and sensitivity on the

dangers of these chemicals. The increased awareness of what these chemicals are in the first instance and

the danger involved from exposure will go a long way in ensuring reduced risk to public health and the

environment. Working with SAICM (The Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management) and

the IOMC (The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals), emphasis is placed

on informing the public through audio-visual means and wherever possible, in the local language and using

appropriate awareness strategies.

A global source profile

Currently, the Stockholm Convention obliges Parties to the Convention to carry out source profiles for those

substances under that Convention. In order to keep track of what is happening, a global profile of selected

priority chemicals would be undertaken on a timely basis to provide useful information on the production,

emissions and releases of certain PTSs. Such a programme would rely on relevant, existing, global and

regional data centres as well as the global monitoring network being established. It would make use of the

wide network already developed through the RBA PTS Project as a means of collecting vital country and

regional information for assessment. The SAICM should consider this recommendation as part of its

portfolio.

A global strategy for technology transfer

In the past the transfer of technology has on occasion not been appropriate given the differences in

geography, development of supporting institutions, culture and language. In order to ensure maximum

benefit from the transfer of technology to reduce the release and emissions of PTS and subsequent effects to

the environment, an agreed strategy would be developed that has the acceptance of all stakeholders. It is

recommended that the SAICM consider in its work the importance of technology transfer and the need for it

to reflect national requirements and situations, and to consider developing guidance on this matter.

Development of capacities and predictive capability of the LRT of PTS

For most of the regions of the globe no quantitative region-specific tools for transport assessment exist. The

three major reasons for that are: Lack of region-specific process and understanding; lack of sufficient/and or

sufficiently good data for model input and a lack of capacity for developing and using transport models

within the regions. This knowledge gap not only prevents a quantitative treatment of PTS fate, but may often

impede even a conceptual qualitative understanding of PTS transport behaviour in regions other than the

Northern temperate environment. Therefore, there is need to gain a quantitative understanding and predictive

capability of the transport and accumulation behaviour of various PTS under a variety of geographic and

climatic circumstances, that reflect the diversity of the entire global environment. To achieve this, the

following should be undertaken: a) Conduct studies aimed at a quantitative understanding of fate processes

that are both unique and important for the transport behaviour of PTS under various regional circumstances.

Specifically, identify PTS fate processes of importance in polar, arid and tropical ecosystems and investigate

them with the aim to derive quantitative information suitable for inclusion into regional and global fate and

transport models for PTS. Such fate processes may include phase partitioning, air-surface exchange,

contaminant focussing and degradation processes; b) Ensure there are resources and capacity for monitoring

PTS in remote environments. Models and a quantitative understanding of fate processes can not substitute for

field data, but are dependent on them; c) Support the development, improvement, evaluation and use of

regional and global PTS transport models of variable complexity; and d) Build capacity within the regions

for studying and modelling PTS transport processes.

14

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1

BACKGROUND

There is considerable concern amongst Governments, Non-Governmental Organisations, scientists and the

wider community over potential adverse effects on the environment and human health from exposure to

chemicals. The long life times and potential for long-range transport of certain chemical pollutants requires

that concerted international action is put in place to effectively control exposures since such chemicals

released in one place may have impacts at a considerable distance from the source.

In 1997 the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Governing Council decided that immediate

international action should be initiated to protect human health and the environment through measures which

will reduce and/or eliminate the emissions and discharges of an initial set of twelve "persistent organic

pollutants" (POPs). International negotiations resulted in the adoption of the Stockholm Convention on

Persistent Organic Pollutants in May 2001. The 12 substances initially addressed in the Stockholm

Convention are: aldrin, endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, toxaphene, mirex, heptachlor, hexachlorobenzene,

polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polychlorinated dibenzodioxins (PCDD) and polychlorinated

dibenzofurans (PCDF). Criteria are set out by which other chemicals will be considered for addition to the

Convention.

The present project was initiated in mid-1998 at a time when the negotiations for an international legally

binding instrument for implementing international action on certain persistent organic pollutants had just

started and while the outcome of the negotiations was still purely conjectural. It was initiated by GEF after

discussions with UNEP to address a broader set of issues and substances than those which finally were

agreed under the Stockholm Convention on POPs. This project therefore deals with "persistent toxic

substances" or PTS and is deliberately looking at a wider group of chemicals than the twelve POPs under the

Stockholm Convention. PTS is a descriptive term and does not reflect a narrow definition of chemical

properties or a legal definition but rather is used as an umbrella term for compounds that show persistence in

the environment (and hence may have effects at some distance from their source and for some time after they

are released) and which are toxic. The project was designed to compile and evaluate existing data on PTS. It

was not intended to be a formal risk or hazard assessment. Inclusion of a chemical as PTS within this project

does not imply that there is necessarily any given level of risk or imply a need for a specific action

(regulatory or otherwise) but that the chemical properties in terms of persistence and potential toxicity mean

that further assessment at the regional or international level may need to be undertaken as a basis for such

action, as appropriate.

Persistent toxic substances may be manufactured intentionally for use in various sectors of industry. One

important sub-group is pesticides, others may be formed as by-products from a variety of processes

(industrial, non-industrial and natural) including combustion. To date, scientific assessments have often been

focused on specific local and/or regional environmental and health effects, in particular "hot spots" such as

the Great Lakes region of North America or the Baltic Sea in Europe.

1.2

OBJECTIVES

The objective of this project, as stated in the project brief, was to deliver a measure of the nature and the

comparative severity of damage and threats posed at national, regional and ultimately at global levels by

Persistent Toxic Substances (PTS).

In order to address this overall objective a number of sub-objectives were developed:

To establish a regionally based network of experts and teams to gather and evaluate data on

PTS

To set up a framework for broad-based stakeholder input within regions to determine regional

priority issues related to PTS

To gather available data on sources of selected PTS within each region

To gather available data on concentrations of PTS in the environment, including animals and

humans

To gather available information on the effects of PTS on humans and ecosystems

15

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

To gather available information on the long-range transport of PTS

To gather from the regions available information on the management of PTS and barriers to

improved management

To develop regional reports containing the findings of the work

To hold a global priority setting meeting to review the results and priorities of the global

assessment

To develop a global report synthesizing the results from the regions and identifying key

priority areas, recommendations for future action and data gaps.

1.3

SCOPE OF PROJECT

The project was designed to meet the objectives outlined above using a regionally based team approach and

using existing data available within the regions.

The project combines two aspects of the PTS issue it is underpinned by a science-based assessment and as

such it has gathered, analysed and presented information and also drawn together stakeholders in the regions

to discover their priority issues related to PTS. The project has been carried out independently of actions

related to the negotiation and implementation of any international, regional or national agreements or policies

and while it may help to provide information to such processes it was not designed and implemented with

that objective.

The scope and impact of PTS are very broad with sources from many activities and practices, a wide range of

chemicals, multiple pathways of exposure and highly variable behaviour in the environment as well as a wide

variation in toxicities. The persistence and widespread occurrence and low absolute levels of PTS present

challenges to those authorities and scientists studying PTS. Analytical data can be expensive to acquire and

may have limited application. Providing a firm foundation for assessment and possible action to prevent and

mitigate potential effects of PTS requires a holistic approach to data gathering, assembly and assessment

often based on limited data. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific

certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental

degradation.

1.4

METHODOLOGY

The project was designed to be based in the regions and draw on the resources and expertise at the country

level. Regional teams were set up to be responsible for collecting the data, implementing technical

workshops and making the regional assessment. UNEP provided central project management and

coordination functions and guidance was provided from the centre in order to facilitate a consistent approach.

A Steering Group made up of representatives of relevant international organisations, environmental and

industrial non-governmental organisations and scientists provided assistance to the Project Manager in

guiding and delivering the project.

1.4.1 The Regions

For this project the globe was partitioned into twelve regions. The twelve regions were linked to important

international waters in keeping with the focus of the project and designed to provide a manageable structure

for the project execution. The twelve regions were:

I Arctic

VIII - South East Asia and South Pacific

II - North America;

IX - Pacific Islands

III Europe

X - Central America and the Caribbean

IV Mediterranean

XI - Eastern and Western South America; and

V - Sub-Saharan Africa

XII - Antarctica.

VI - Indian Ocean

VII - Central and North East Asia (Western North

Pacific)

16

INTRODUCTION

1.4.1.1

Region I Arctic

The regional boundaries used were those set for the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Project (AMAP).

The region includes the Arctic regions of the eight circumpolar countries: Canada, Denmark (Greenland);

Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States of America (USA). Climate varies

considerably with maritime climates along the coast of Norway, adjoining parts of the Russian coast and a

narrow coastal strip of Alaska. A continental climate is found from northern Scandinavia to Siberia and

eastern Alaska to the Canadian Arctic archipelago.

Much of the Arctic region is lightly populated and not industrialised, however, heavy industry in or near the

Arctic parts of Russia and Scandinavia, historical equipment uses and waste disposal practices may be

significant sources of PTS. In addition various PTS have found uses within the Arctic region.

1.4.1.2

Region II North America

Region II consists of the Canada the USA and Mexico except the Arctic parts of Canada and the USA

(Region I) and Hawaii (Region IX). Climatic variation is large from Arctic in the north to tropical in the

south.

The USA and Canada are developed, industrialised countries with sophisticated industry and regulation,

Mexico is a developing country with increasing industrialisation.

1.4.1.3

Region III Europe

The Europe region for this project consists of Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria,

Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Georgia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Liechtenstein,

Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation,

Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. It excludes

those parts of the countries assessed under Region I (Arctic).

Region III spans three climatic zones the circumpolar zone in the north, the subtropical zone south of the

Alps including the Dinaric alps and the Balkans and the temperate zone warm in the central and southern

area and cool in the north.

The countries included in Region III range from highly industrialised economies (such as Germany and the

UK) to countries with economies in transition including some with aged industrial infrastructure to those

with greater reliance on agriculture and a developing economic structure.

The chemical industry, metal production and processing and agriculture are all significant parts of the

economy.

17

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

1.4.1.4

Region IV Mediterranean

Region IV consists of countries clustered around the Mediterranean Sea: Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Bosnia-

Herzegovina, Croatia, Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Libyan Arab

Jamahiriya, Malta, Monaco, Morocco, Palestine, Portugal, San Marino, Slovenia, Spain, Syrian Arab

Republic, The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Tunisia, Turkey and Yugoslavia.

The climate is generally characterised by mild wet winters and hot dry summers with more than 90% of

annual precipitation falling in winter.

Much of the population and urban development occurs along the coastal strip. Large variations are observed

in the levels of development, ranging from highly industrialised economies of such as France, Italy and Spain

through industrialising countries such as Greece and Turkey to developing countries in the south.

1.4.1.5

Region V Sub-Saharan Africa

The region consists of the following countries and island states: Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso,

Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Brazzaville), Cote d'Ivoire,

Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana,

Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius,

Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone,

Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The region can be divided into three major regions the Northern Plateau, the Central and Southern Plateau

and the Eastern Highlands. The equatorial belt has rainfall whereas the northern and southern African

countries and those in the Horn of Africa are typically arid or semi arid.

In general the African economy is fragile and largely agricultural and high debts contribute to comparatively

low levels of industrialisation and development. Most industrial areas are located close to lakes, rivers and

estuaries.

1.4.1.6

Region VI Indian Ocean

The region consists of Bahrain; Bangladesh; Bhutan; India; Iran; Iraq, Kuwait; Maldives; Nepal; Oman;

Pakistan; Qatar; Saudi Arabia; Sri Lanka; the United Arab Emirates and Yemen. Climate varies considerably

across this region covering mountain environments through to coastal and desert environments.

The economies and levels of development and income also vary strongly across the region with some

countries deriving high incomes from oil production and others with largely agricultural and undeveloped

economies.

1.4.1.7

Region VII Central and North East Asia

The region consists of eleven countries: Afghanistan, China; Japan; Republic of Korea; Democratic People's

Republic of Korea; Russian Federation (excluding the Arctic part Region 1 and western part Region III);

Mongolia; Kazakhstan; Kyrgyzstan; Tajikistan; Turkmenistan; and Uzbekistan. Region VII includes a

continental landmass, several major islands and various bodies of water with mountains, plains and deserts.

The major part of the population is concentrated in the eastern half of the region. The region has countries

which are in the process of rapid development with increasing industrialisation and mineral and oil

production, highly industrialised economies in transition and fully developed industrial economies. In

addition some areas are at an earlier stage of development.

1.4.1.8

Region VIII Southeast Asia and the Pacific

The region consists of: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People's Democratic

Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet

Nam.

Climate ranges from tropical (Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea) through to semi temperate conditions

in the continental plateau and the mountains. The climate in Australia is generally arid or semi arid, it is

temperate in the south and tropical in the north. New Zealand is temperate with some regional contrasts.

The sub-region remains very diverse in terms of economic development, political systems, ethnicity, culture,

and natural resources. Singapore, for example, is an OECD country and Brunei Darussalam, an oil-rich

18

INTRODUCTION

microstate, Myanmar, Lao People's Democratic Republic, and Cambodia are essentially agrarian economies,

while Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Viet Nam are rapidly industrializing. Australia and

New Zealand are developed countries with mixed economies and substantial agricultural sectors.

1.4.1.9

Region IX Pacific Islands

The region is very diverse. Twenty two countries and territories were included in this region: American

Samoa; Cook Islands; Federated States of Micronesia; Fiji; French Polynesia; Guam; Kiribati; Marshall

Islands; Nauru; New Caledonia; Niue; Northern Mariana Islands; Palau; Pitcairn Islands; Samoa; Solomon

Islands; Tokelau; Tonga; Tuvalu; Vanuatu; Wallis and Funtuna; and various other US territories.

The islands are spread across more than 30 million square kilometres of which more than 98% is ocean. Of

7500 islands about 500 are inhabited. Countries and territories range from single islands to groupings of

more than 100. Some islands are mountainous, others are low lying atolls. Economies tend to be based on

agriculture and fishing.

1.4.1.10

Region X Central America and the Caribbean

Region X consists of the countries of: Antigua and Barbuda; Bahamas; Barbados; Belize; Bermuda;

Colombia; Costa Rica; Cuba; Dominica; Dominican Republic; El Salvador; Grenada; Guatemala; Guyana;

Haiti; Honduras; Jamaica; Nicaragua; Panama; Puerto Rico; Saint Kits and Nevis; Saint Lucia; Saint Vincent

and the Grenadines; Suriname; Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela. In general the climate is tropical.

The economies of many countries used to be largely agricultural. However, development of mining in

Venezuela, Guyana and Suriname, tourism in the Caribbean and, latterly, increasing manufacturing have

somewhat reduced the dominance of agriculture.

1.4.1.11

Region XI Eastern and Western South America

This region consists of eight countries: Argentina; Bolivia; Brazil; Chile; Ecuador; Paraguay; Peru and

Uruguay. Climate varies considerably across the region from tropical in the north through more temperate to

desert with high mountains with alpine conditions.

The economies range from relatively undeveloped through those based on exploitation of mineral and other

natural resources through to the large economy of Brazil (in the top 10 countries worldwide in terms of

GDP).

1.4.1.12

Region XII Antarctica

This region was not defined by national boundaries but rather by setting geographical limits. The region

included all land and ocean south of 50°S from 50°W to 30°E; south of 45°S from 30°E to 80°E; south of

55°S from 80°E to 150°E; and south of 60°S from 150°E to 50°W, as well as Ile St Paul and Ile Amsterdam,

Macquarie Island and Gough Island.

The region is remote, land mass has cold desert conditions with much of the land permanently covered by

ice. Islands within the region range from permanently snow covered to more temperate conditions with more

developed terrestrial ecosystems.

There is no indigenous population or industrial activity.

1.4.2 Structure (regional teams)

The basic functional unit for the project delivery was the "Regional Team"1. Each Regional Team consisted

of a regional coordinator appointed by UNEP and a team of four or five team members selected by the

coordinators and approved by the Steering Group. The regional team was responsible for project planning

and execution at the regional level.

1 The approach in three regions was significantly different. The assessment of Region I was carried out by a contractor

working for the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) and was based on the existing AMAP report

(AMAP 1998), the Arctic report for the RBA was reviewed. In region II a contractor compiled the report and only a

priority setting meeting was undertaken. The work of Region XII was delegated to the Scientific Committee on

Antarctic Research (SCAR) who in turn subcontracted the work.

19

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

A network of experts was assembled at the country level. These experts were drawn from academia,

Government, industry and non-Governmental Organisations and provided data and information to the

regional teams for use in the assessment, in part through participatory regional workshops. Establishing and

operating the network presented some challenges but after initial teething troubles some regions found the

process valuable and effective. This was especially true where there was little previous experience in

working with such networks and where basic infrastructural weaknesses were an issue.

Central project management and direction was provided by UNEP Chemicals in Geneva to ensure that

regions were working in a compatible manner and to provide guidance on common issues that arose.

Due to the particular circumstances of the Arctic and Antarctic no regional meetings were held.

1.4.3 Approach

This project was based on the collection, synthesis and analysis of existing data. There is a considerable

quantity of existing data available relating to the sources, environmental levels, transport and effects of a

variety of PTS.

The project was based on a regional structure to ensure that, in so far as possible, the conclusions and

priorities were based on the specific situation and circumstances in the different regions.

It is important to evaluate what is known in the regions, what are the perceived priorities and where the major

data gaps and deficiencies are. This will provide GEF and UNEP with a soundly-based rationale for

assigning priorities for future action on chemical issues and help to direct a focused and cost-effective

programme of future work by countries and regions.

The Regional Teams were responsible for data gathering and assembly. One tool that was developed to

assist in this data gathering was a standard data input form or questionnaire. Some Teams made more use of

the standard questionnaires than others. It was clear that when dealing with complex and disparate data from

a wide variety of sources with no control or influence over the studies from which data were being collected,

there is no simple and effective system that will easily and adequately handle the information. In some

regions comparatively greater use was made of data in the general scientific literature (in the case of Region

XII all data came from this source).

A key feature of the data gathering part of the project was that an invitation was extended very widely for

data. Information was sought from governments, research institutions, academics, non-governmental groups

and industry. The nature of the project was such that although the reports and findings were widely

disseminated there was no formal process of review by governments.

Workshops were organised in the relevant regions to bring together interested parties, to brief them on the

project and to gather feedback and data relevant to the project. In general a two-stage approach was taken to

have a workshop on sources and concentrations of PTS in the environment and a second on toxicological and

ecotoxicological impacts and transboundary movement of PTS.

Regional Priority Setting Meetings were organised in which participants were involved in a process designed

to discover what the key priorities related to PTS amongst the stakeholders were. Participation was taken

from representatives of governments, industry, NGOs, and scientists from within each respective region.

This process drew both on analytical and related data as well as the perceptions of risk and harm amongst

stakeholders.

To assist with the process of setting priorities, a simple scoring system was developed. The participants were

asked to assign a "score" to the chemicals. The score could be 0, 1 or 2 and relating to different aspects of

PTS knowledge: sources; levels; effects and gaps. A score indicated no concern (0), local concern (1), and

regional concern (2), while for gaps 0 indicated that supporting data were available, 1 that the data were

limited, and 2 that data were largely missing.

The holding of and outputs from the Regional Priority Setting Meetings provide a powerful tool in the study

of PTS and how the problems are perceived in the Regions by a broad group of stakeholders. The results

from this exercise gave an overview of the various aspects of the occurrence of PTS within a Region and

integrated perceptions and data. Nevertheless, precaution should be taken when looking at this dataset as a

basis to prioritise PTS and hence to orientate future research and actions. Inevitably, the judgements

expressed by participants usually reflected their specific experience, knowledge and perception of the

20

INTRODUCTION

problems and often for a specific country only. Such a simple scoring system restricts the depth of

information and the results should be used as a part of a wider assessment and not taken as definitive for a

region.

The findings of the project were summarised in 12 regional reports (see reference list). The overall findings,

key themes and examples from the regional reports have been assembled into this report but for a full picture

of the work carried out and data gathered, the regional reports should be used alongside this global report.

The project was separate from and independent of activities related to the negotiation and subsequent

implementation of the Stockholm Convention although findings from this work may be of relevance to

entities working on the Stockholm Convention.

1.4.4 Persistent Toxic Substances - PTS

This project is concerned with a group of chemicals that are termed "Persistent Toxic Substances" or PTS.

There is no formal or legal definition of PTS but rather the concept was developed during the project

development phase to encompass chemicals that could be of concern due to their potential toxicity to

ecosystems or humans. These chemicals exhibited characteristics of environmental persistence so that long-

term exposures might result and effects may be felt some distance from the point of production or release.

The project was developed with the explicit intention to consider a broader range of chemicals and issues

than the 12 POPs that were the subject of the negotiations to develop a legally binding agreement which led

ultimately to the Stockholm Convention. The number of possible chemicals that could meet the definition of

being PTS is very large. In order to ensure that the project was both consistent and at the same time able to

be responsive to the priorities of the regions the following approach was taken: all regions would consider the

12 designated "Stockholm POP" chemicals, they would also be able to select additional chemicals that were

of concern within the region.

In order to help the regions in selecting PTS chemicals a listing was compiled and provided to the regions for

their consideration. This list was drawn from chemicals which could be grouped as PTS and which had been

considered for action or assessment in other programmes. Information relevant to the process for deriving

the list and a discussion of the selection of PTS at the planning workshops and in the project initiation is

described in the Guidance Document issued at the beginning of the project (UNEP 2000).

This project was primarily concerned with data gathering and not with assessing which chemicals are or

could be considered PTS. The inclusion of a chemical for assessment does not imply that it meets any

particular criteria of toxicity, persistence or effect. It is crucial to recognise that the exclusion of chemicals

from this assessment does not imply that there are not other potential PTS that may be important.

The project provides information on those chemicals that were considered and is based on the information

and data provided during the project period. Supplementary data and further studies may change the relative

priorities and may change the interpretation of the data available. The work is therefore to be seen as a step

in the process of evaluating PTS and not as a definitive study and all conclusions are drawn with that in

mind.

The chemicals considered in each region are shown in Table 1. Most regions considered chemicals selected

from the list of provided by UNEP but some added additional chemicals as well. Since only limited data are

available in some regions, the fact that a chemical was not considered does not necessarily mean that it is not

present or not necessarily a priority. The listing is broken down to show those chemicals defined as

"Stockholm POPs", and "other PTS" which are grouped according to their primary use or designation as

pesticides, industrial chemicals or unintentionally produced PTS.

Some chemicals will have multiple uses and these may all need to be considered. Hexachlorobenzene may

be used as a pesticide, an industrial chemical and can also be unintentionally produced, while PAHs are

usually produced unintentionally but are also produced for use as an industrial chemical.

21

RBA PTS GLOBAL REPORT 2003

Table 1

Chemicals considered in the regions.

I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII

Aldrin

"Stockholm POP"

pesticides

Chlordane

DDT

Dieldrin

Endrin

Heptachlor

Mirex

Toxaphene

Hexchlorobenzene

(HCB)

POP industrial

Polychlorinated

chemicals

biphenyls (PCBs)

POP unintentionally Dioxins (PCDDs)

produced

Furans (PCDFs)

Other PT

Atrazine

S

pesticides

Lindane (HCH)1

Hexachlorocyclohexanes

(HCH)1

Chlordecone

Pentachlorophenol

Endosulphan

Organotin

Organolead

Other PTS -

industrial

Hexabromobiphenyl

(HxBB)

Polybrominated

diphenyl ethers (PBDE)

Phthalate esters

Short-chain chlorinated

paraffins (SCCPs)

Nonyl/octyl phenols

Perfluorooctane

sulfonate (PFOS)

Other PT

Organomercu

S

ry

unintentionally

Polycyclic aromatic

produced

hydrocarbons (PAH)

Note 1 potential confusion arises since lindane is an isomer of the HCH grouping, some data refer

specifically to lindane, other data are more general and related to HCH. Treatment by the regions was not

always consistent.

22

INTRODUCTION

1.5

PURPOSE AND STRUCTURE OF GLOBAL REPORT

The outputs from the Regionally Based Assessment (RBA) include:

Twelve regional reports addressing the findings of the project at the regional level including

regional priorities developed by stakeholder meetings;