United Nations

Environment Programme

Chemicals

Pacific Islands

REGIONAL REPORT

Regionally

Based

Assessment

of

Persistent

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals

11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone : +41 22 917 1234

Fax : +41 22 797 3460

Substances

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

December 2002

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and

Printed at United Nations, Geneva

Economics Division

GE.03-00161January 2003300

UNEP/CHEMICALS/2003/9

G l o b a l E n v i r o n m e n t F a c i l i t y

UNITED NATIONS

ENVIRONMENT

PROGRAMME

CHEMICALS

Regional y Based Assessment

of Persistent Toxic Substances

American Samoa, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji,

French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New

Caledonia, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Pitcairn Islands,

Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Wallis

and Futuna, Other US territories

PACIFIC ISLANDS

REGIONAL REPORT

DECEMBER 2002

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY

This report was financed by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through a global project with co-

financing from the Governments of Australia, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States of

America.

This publication is produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound

Management of Chemicals (IOMC).

This publication is intended to serve as a guide. While the information provided is believed to be

accurate, UNEP disclaim any responsibility for the possible inaccuracies or omissions and

consequences, which may flow from them. UNEP nor any individual involved in the preparation of

this report shall be liable for any injury, loss, damage or prejudice of any kind that may be caused by

any persons who have acted based on their understanding of the information contained in this

publication.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations of UNEP

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning

the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), was

established in 1995 by UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO and OECD (Participating

Organizations), following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on

Environment and Development to strengthen cooperation and increase coordination in the

field of chemical safety. In January 1998, UNITAR formally joined the IOMC as a Participating

Organization. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and

activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the

sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the environment.

Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested

together with a reference to the document. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or

reprint should be sent to UNEP Chemicals.

UNEP

CHEMICALS

UNEP Chemicals11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 917 8170

Fax:

+41 22 797 3460

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and Economics Division

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE.................................................................................................................... VI

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... VIII

1

INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1

1.1

OVERVIEW OF THE RBA PTS PROJECT .............................................................................1

1.1.1 Objectives ...............................................................................................................................1

1.1.2 Results.....................................................................................................................................1

1.2 METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................................2

1.2.1 Regional

Divisions..................................................................................................................2

1.2.2 Management

Structure............................................................................................................2

1.2.3 Data

Processing.......................................................................................................................2

1.2.4 Project

Funding.......................................................................................................................2

1.3

DEFINITIONS OF PTS CHEMICALS .....................................................................................2

1.3.1 -

Pesticides ..............................................................................................................................3

1.3.2

- Industrial compounds ...........................................................................................................6

1.3.3

- Unintended by-products .......................................................................................................6

1.3.4 -

Regional

specific ..................................................................................................................6

1.4

DEFINITION OF THE PACIFIC REGION ............................................................................10

1.5 PHYSICAL

SETTING .............................................................................................................10

1.5.1 Regional

Diversity ................................................................................................................10

1.5.2

The role of the ocean.............................................................................................................10

1.5.3

Geographical Variations: High Islands and Low Atolls.......................................................11

1.5.4 Population

Variations ...........................................................................................................11

1.5.5 New

health

concerns.............................................................................................................12

1.5.6 Fragile

economies .................................................................................................................13

2

SOURCE CHARACTERISATION.................................................................14

2.1 BACKGROUND

INFORMATION TO PTS SOURCES ........................................................14

2.1.1 Pesticides ..............................................................................................................................14

2.1.2

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) .......................................................................................14

2.1.3 Organolead

Compounds .......................................................................................................14

2.1.4

Dioxins, furans and other unintentional byproducts.............................................................14

2.1.5 Organtin

Compounds ............................................................................................................15

2.1.6

Other PTS Chemicals............................................................................................................15

2.2

DATA COLLECTION AND QUALITY CONTROL ISSUES...............................................15

2.3

PRODUCTION, USE AND EMISSION..................................................................................15

2.3.1

Current Pesticide Use............................................................................................................15

2.3.2

Emissions of Unintentional Byproducts ...............................................................................15

2.3.3

Other PTS Chemicals............................................................................................................16

2.4 HOT

SPOTS .............................................................................................................................16

2.5 DATA

GAPS ............................................................................................................................17

2.6

SUMMARY OF THE MOST SIGNIFICANT REGIONAL SOURCES ................................17

2.7 CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................................................................17

iii

3

ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGY AND

ECOTOXICOLOGY PATTERNS ..................................................................19

3.1 LEVELS

AND

TRENDS .........................................................................................................19

3.1.1

ANALYSIS BY INDIVIDUAL PTS ...................................................................................19

3.1.2

PTS IN PICs BY SAMPLE TYPE .......................................................................................20

3.1.3 Trends ...................................................................................................................................24

3.2

TOXICOLOGY OF PTS OF REGIONAL CONCERN...........................................................24

3.2.1

Toxicology by Individual PTS and Toxicological Data in the Pacific Islands...............................25

3.3

ECOTOXICOLOGY OF PTS OF REGIONAL CONCERN...................................................28

3.4 DATA

GAPS ............................................................................................................................28

3.5 CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................................................................28

4

ASSESSMENT OF MAJOR PATHWAYS OF TRANSPORT....................30

4.1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................30

4.2

OVERVIEW OF EXISTING MODELLING PROGRAMMES AND PROJECTS ................30

4.2.1

General features / Regionally specific features ....................................................................30

4.3 ATMOSPHERE........................................................................................................................30

4.4 OCEANS ..................................................................................................................................31

4.5 FRESHWATER

AND

GROUNDWATER..............................................................................31

4.5.1

Local Water Discharges........................................................................................................31

4.5.2 River

Discharges...................................................................................................................31

4.5.3 Groundwater .........................................................................................................................31

4.6 BIO-TRANSPORT ...................................................................................................................32

4.6.1 Traditional

transport..............................................................................................................32

4.7 DATA

GAPS ............................................................................................................................32

4.8 CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................................................................32

4.9 RECOMMENDATIONS..........................................................................................................33

5

PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE REGIONAL

CAPACITY AND NEEDS TO MANAGE PTS..............................................34

5.1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................34

5.2 MONITORING

CAPACITY....................................................................................................34

5.3

EXISTING REGULATIONS AND MANAGEMENT STRUCTURES .................................34

5.4

STATUS OF ENFORCEMENT...............................................................................................34

5.5

ALTERNATIVES OR MEASURES FOR REDUCTION.......................................................36

5.6 TECHNOLOGY

TRANSFER..................................................................................................36

5.7 IDENTIFICATION

OF

NEEDS ..............................................................................................36

6

FINAL RESULTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS........................................37

6.1 IDENTIFICATION

OF

BARRIERS........................................................................................37

6.2 IDENTIFICATION

OF

PRIORITIES......................................................................................37

6.2.1 Priority

PTS ..........................................................................................................................37

6.2.2 Priority

Needs .......................................................................................................................38

6.3

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE ACTIVITIES..........................................................39

iv

ANNEX 1: REFERENCES .........................................................................................41

ANNEX II: LIST OF ACRONYMS..........................................................................43

ANNEX III: RESULTS FROM DATA COLLECTION ........................................44

ANNEX IV: SCORING OF CHEMICALS...............................................................53

v

PREFACE

Overview of the global project

The introduction of xenobiotic chemicals that are generally referred to as "persistent toxic substances" (PTS)

into the environment and resulting effects is a major issue that gives rise to concerns at local, national, regional

and global scales. Many of the substances of greatest concern are organic compounds characterised by

persistence in the environment, resistance to degradation, and acute and chronic toxicity. The lipophilic

character of these substances causes them to be incorporated and accumulated in the tissues of living organisms

leading to body burdens that pose potential risks of adverse health effects. There is a need for a scientifically-

based assessment of the nature and scale of the threats to the environment and its resources posed by persistent

toxic substances that will provide guidance to the international community concerning the priorities for future

remedial and preventive action.

The UNEP Governing Council in its decision 19/13C on POPs, concluded that international action is required

to reduce the risks to human health and the environment arising from the releases of the 12 specified POPs. The

Governing Council further identified the need to develop science-based criteria and a procedure for identifying

additional POPs as candidates for future international action and recognised the need to develop an instrument

that would take into account differing regional conditions.

The GEF/UNEP Regionally-Based Assessment of Persistent Toxic Substances project was developed in

response to these needs. The project has relied upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and

information as the basis for assessment. No research was undertaken to generate primary data, but projections

have been made to fill data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment. The proposed activities

were designed to obtain the following expected results:

i.

Identification of major sources of PTS at the regional level;

ii.

Impact of PTS on the environment and human health;

iii.

Assessment of transboundary transport of PTS (both within and between regions);

iv.

Assessment of the root causes of PTS related problems, and regional capacity to manage these

problems; and

v.

Identification of regional priority PTS related environmental issues.

The Pacific Islands Region is one of twelve covering the globe. Each region was tasked with contributing a report

on the priorities for PTS that pose a threat, and/or cause damage or deleterious environmental effects in the region.

This report, along with those from other regions will be used to derive a global report on the selected PTS.

The information contained in this report was originally assembled by a small Regional Team, working in

conjunction with a much wider network of Regional Experts. The initial findings of the Team were presented and

discussed at a Regional Technical Workshop, which was held in Apia, Samoa, 14-17 May 2002. The revised

draft report was then presented to a Regional Priority Setting Meeting in Nadi, Fiji, 27-30 August, 2002, and the

outcomes of that meeting are reflected in the contents of this report.

Composition of the Regional Team

The members of the Regional Team were chosen on the basis of the following criteria:

Each member should have extensive technical and scientific experience on PTS related subjects;

Each member should be recognised and respected in their country and in the sub-region as competent in the

PTS field;

The members should come from differing countries to represent a cross-section of the region;

Members should be selected to ensure that competence resides to undertake the writing of the various

chapters of the regional report including the chapter on regional capacity, the socio-economic profile and

root causes of PTS;

Each member should be accessible by email and have internet access;

Each member should have administrative and technical support of a recognised institution; and

Each member should be fluent in English.

The Team Members thus chosen, were as follows:

vi

Regional Coordinator

Dr Bruce Graham, Pollution Prevention Coordinator, South Pacific Regional Environment Programme

(SPREP), Apia, Samoa

Team Members

Prof. Bill Aalbersberg, Professor of Natural Products Chemistry, University of the South Pacific, Fiji

Ms Michelle Rogow, Environmental Engineer, Emergency Response Section, Region IX, US Environmental

Protection Agency, San Francisco, USA

Dr Pita Taufatofua, Deputy Director and Head of Research and Extension, Ministry of Agriculture & Forestry,

Tonga

Other

Prof. John Morrison of the University of Woolongong, NSW, Australia, was engaged to act as a Technical

Advisor to the Team, and to facilitate the regional meetings. Professor Morrison is BHP Professor of

Environmental Science, and Coordinator of the Oceans and Coastal Research Centre.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the willing assistance from members of the Regional Network

who provided information on PTS chemicals within the region. The invaluable contributions from the

participants at the Regional Technical Workshop and the Regional Priority Setting Meeting are also gratefully

acknowledged.

Funds for the project were provided by the Global Environment Facility through UNEP Chemicals. We also

acknowledge financial support from the New Zealand Official Development Assistance programme, which

supported some of the SPREP input to this work.

vii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

This report provides a regional review of the production, use, environmental impacts and environmental

transport of the group of chemicals know as persistent toxic substances (PTS). The introduction of these

chemicals into the environment and resulting effects is a major issue that gives rise to concerns at local,

national, regional and global scales. The report is intended as a scientifically-based assessment of the nature

and scale of the threats to the environment and its resources posed by past and present uses of persistent toxic

substances both within the region and beyond. It is intended to contribute to a global assessment of PTS that

will provide guidance to the international community concerning future priorities for national, regional and

global activities in this area.

For the purposes of this study, the Pacific Islands Region was defined as that area encompasing all of the

independent island states and territories within the Pacific Ocean, with the exception of Papua New Guinea.

The review was based on existing information only, and did not involve any original research. The information

for the review was assembled by a small Regional Team on the basis of information supplied from a wide range

of people throughout the region and beyond (the Regional Network).

PTS CHEMICALS OF INTEREST TO THE REGION

The chemicals included in this review were the 12 chemicals covered under the Stockholm Convention on

Persistent Organic Pollutants, plus several other PTS chemicals. The 12 Stockholm chemicals are aldrin,

chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, dioxins and furans, endrin, hexachlorobenzene, heptachlor, mirex, polychlorinated

biphenyls (PCBs) and toxaphene. Information was also obtained on endosulphan, hexachlorocyclohexanes

(HCH) , phthalate esters, polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pentachlorophenol, and organolead, organotin

and organomercury compounds. Other chemicals considered for inclusion in the survey were, atrazine,

chlordecone, hexabromobiphenyl, polybrominated biphenyl ethers, chlorinated paraffins, octylphenols, and

nonylphenols. However, no data was found for any of these chemicals, although this does not preclude their

existence within the region.

SOURCES OF PTS

There is no manufacture in the region of any of the PTS chemicals covered in this report, although many of

them are known to have been used in the region. The current usage of PTS pesticides in the region is low, and

should be eliminated over the next 10 years or so. Existing stockpiles of PCBs and PTS pesticides should also

be eliminated over the next few years. There is no evidence of PCBs being actively used in the region although

small quantities are believed to still exist in a few in-use transformers. No information has been obtained on

the use or otherwise of organlead and organomercury compounds.

Numerous hot spots have been identified, consisting mainly of stockpiles of hazardous wastes and obsolete

chemicals, pesticides and transformer oils. Over 100 contaminated sites were identified, of which 54 were

assessed as needing major remediation work. These sites include PCBs, buried pesticides, pesticides storage,

timber treatment and rubbish dumps. Significant efforts will be required for remediation of these sites.

Generally, there is lack of data on the emissions of dioxins, furans and other complex organics from

combustion processes and other sources in the region. Some estimates of dioxin emission have been made for

some of the countries, on the basis of existing fuel use data.

ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS

The amount of available data on environmental levels of PTS in the region is extremely limited. Of those

samples analysed, the majority have been environmental media (air, water, sediment and marine organisms

used as pollution indicators). Hardly any data exists for levels in humans (plasma, milk, fat). Drinking water

and food analyses are also very limited. Many Pacific Island countries appear to have had no PTS analyses

performed.

A large number of samples had detectable levels of PTS, owing both to local usage and global transport,

especially by wind currents. PTS were recorded in some samples for which there is no record that that

particular chemical was ever imported into that country. This could indicate either illegal entry or

environmental transport.

In general, concentrations are relatively low for most samples. There are a few samples, however, especially of

sediments from urban areas, that would lead to a classification as contaminated sites in developed countries,

and warrant remediation. There are also contaminated areas in Micronesia due to past military activities which

have impacted marine food samples.

viii

Overall the highest concentrations of PTS tend to have been found for DDT and its derivatives, especially in

Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands where DDT is used to control malarial mosquitoes, and PCBs, which

have been used as electrical oil insulating material and often disposed of in a haphazard manner. Organolead

and organotin levels are also high in some areas, probably due to their use in gasoline and marine paints

respectively.

TOXICOLOGY

Toxicology of PTS in the Region is in its infancy. Very few toxicological or exposure investigations have been

conducted in the Pacific Islands and even fewer relate to PTS. The only body burden studies found in the

Region were conducted in Samoa in 1979 and the Northern Mariana Islands in 2000. Information from the

neighboring country of Papua New Guinea identified DDT in mothers' milk with one sample above 3 mg/kg

(ppm). This is notable because while most of these pesticides are no longer in use, DDT is still used for

malaria control in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu.

In the absence of comprehensive human health studies and body burden data for this report, chemical

contamination in food sources was assessed, although this data is also very limited. Looking at some of the

more widely utilized PTS around the Region, gives an indication of the impact that use has had on food

sources. The highest levels of DDT in marine foods were found in Fiji shellfish, but once again, the sampling

was extremely limited. In Papua New Guinea, DDT levels in oysters were considerable. Consistent with use,

PCBs have been detected at notable levels in imported foods and in marine foods, especially in former United

States trust territories contaminated by electrical oil residues. In 1979, Samoan fish were found to have the

highest levels of HCHs and heptachlor in the Region. Unfortunately, it was a small sampling and there is no

recent data. Most lead and mercury levels were in the range found in developed countries (mean values around

200 µg/kg wet weight). This is surprising given the low levels of industry in these countries.

While toxicological studies in the Pacific Islands have been limited and human health risks have not yet been

effectively assessed, some data has been gathered, without identification of serious problems. More work is

needed to effectively assess the impact of PTS on human health in the Pacific Islands.

ECOTOXICOLOGY

Impacts from PTS to ecosystems of the Pacific could have a major impact on the economic base of the Pacific

Islands. Many of the Pacific Islands depend on fisheries, agriculture, timber and tourism. Each of these

industries could be heavy impacted by contamination of PTS. When ecosystems are impaired, natural

resources are reduced and economic impacts will follow. Because Pacific Island natural resources are finite

much care should be taken in preservation and impact mimimization.

While no published ecotoxicological data was found in the Pacific, the Regional Team has looked at some of

the work done on non-migratory sea-otters on the Pacific coast of the United States. One study (Jarman, et al,

1996), indicated that PCBs were found in higher concentrations in remote areas of Alaska (Aleutian Islands).

While local military sources may have contributed to these levels, there are also indications that transboundary

movement of PCBs has also contributed to the levels of PCBs found.

While there have been no specific transboundary studies in the Pacific Islands, there are a number of theories

that have been developed regarding transboundary movement of PTS in and out of the Pacific Region. Some of

these theories are supported by studies conducted in the surrounding continents and current work being carried

out relating to climate change issues.

TRANSPORT PATHWAYS

While there have been no specific transboundary studies in the Pacific Islands, there are a number of theories

that have been developed regarding transboundary movement of PTS in and out of the Pacific Region. Some of

these theories are supported by studies conducted in the surrounding continents and current work being carried

out relating to climate change issues.

Transport mechanisms in the Pacific include some typical means, as well as regionally specific features

including the freshwater lens under many islands, highly porous substrata, the possibility of significant

contributions from imported foodstuffs, and large fish movements contributing to PTS transport. Information

on contaminant concentration and pathways of transport in the Pacific Islands is rare.

As mentioned previously, some PTS substances, such as DDT are still in use in some Pacific Island Countries.

These substances may be contributing to more recent loading of PTS into the environment and transport out of

the Region. Extrapolations from other regions indicate that there may be transboundary movement of

contaminants into the Pacific Region and that there are a few special situations of major significance in this

ix

Region. More work on integrating environmental chemistry with other components of the Regional

contamination assessment is urgently required.

ASSESSMENT OF REGIONAL CAPACITY AND MANAGEMENT NEEDS

The Pacific Region currently has very limited capacity to manage PTS and assistance is needed in all areas.

This includes the need for increased monitoring capacity, improved regulations, management structures and

enforcement systems, and perhaps most of all far more people in the region with the skills' knowledge and

experience to implement and utilise all of the above. There are also significant needs in the area of technology

transfer, epsecially in relation to alternatives to the use of PTS and other possible reduction measures.

FINAL RESULTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The Priority PTS for the Pacific Islands region were identified on the basis of the available information

presented at the Regional Technical Meeting and confirmed by the Regional Priority Setting Meeting. A

ranking of the chemicals was produced by scoring each chemical against the guidelines provided by UNEP. It

should be noted though, that this scoring was only done for the categories of Source, Environmental Levels and

Data Gaps. No scores were give for human health or ecotoxicological effects because there was no relevant

data available from within the region. The results of this exercise indicate that DDT, PCBs, dioxins, furans,

PAHs and the organometallic PTS are considered to be the highest priority PTS for the region.

The regional meetings also identified other priority needs for the region, especially in terms of capacity

building. These included priority needs in education, training and community awareness and participation, and

requirements for chemical management systems, technology information and research. These requirements are

addressed in a series of recommendations which are given in Chapter 6 of this report.

x

1 INTRODUCTION

This report provides a regional review of the production, use, environmental impacts and environmental

transport of the group of chemicals know as persistent toxic substances (PTS). The review is based on existing

information only, and did not involve any original research. The information for the review was assembled by

a small Regional Team on the basis of information supplied from a wide range of people throughout the region

and beyond (the Regional Network). The recommendations given in the report on future needs and regional

priorities, were developed during a Regional Technical Workshop and a Regional Priority Setting Meeting.

1.1 OVERVIEW OF THE RBA PTS PROJECT

Following the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety, the UNEP Governing

Council decided in February 1997 (Decision 19/13 C) that immediate international action should be initiated to

protect human health and the environment through measures which will reduce and/or eliminate the emissions

and discharges of an initial set of twelve persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Accordingly an

Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established with a mandate to prepare an international

legally binding instrument for implementing international action on certain persistent organic pollutants. These

series of negotiations have resulted in the adoption of the Stockholm Convention in 2001. The initial 12

substances that have been selected under the Stockholm Convention are: aldrin, endrin, dieldrin, chlordane,

DDT, toxaphene, mirex, heptachlor, hexachlorobenzene, PCBs, dioxins and furans. Beside these 12, there are

many other substances that satisfy the criteria for persistent toxic substances for which their sources,

environmental concentrations and effects are to be assessed

Persistent toxic substances can be manufactured substances for use in various sectors of industry, pesticides, or

by-products of industrial processes and combustion. To date, their scientific assessment has largely

concentrated on specific local and/or regional environmental and health effects, in particular "hot spots" such as

the Great Lakes region of North America or the Baltic Sea.

1.1.1 Objectives

There is a need for a scientifically-based assessment of the nature and scale of the threats to the environment

and its resources posed by persistent toxic substances that will provide guidance to the international community

concerning the priorities for future remedial and preventive action. The assessment will lead to the

identification of priorities for intervention, and through application of a root cause analysis will attempt to

identify appropriate measures to control, reduce or eliminate releases of PTS, at national, regional or global

levels.

The objective of the project is to deliver a measure of the nature and comparative severity of damage and

threats posed at national, regional and ultimately at global levels by PTS. This will provide the GEF with a

science-based rationale for assigning priorities for action among and between chemical related environmental

issues, and to determine the extent to which differences in priority exist among regions.

1.1.2 Results

The project relies upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and information as the basis for the

assessment. No research was undertaken to generate primary data, but projections have been made to fill

data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment. The proposed activities were designed to

obtain the following expected results:

1. Identification of major sources of PTS at the regional level;

2. Impact of PTS on the environment and human health;

3. Assessment of transboundary transport of PTS;

4. Assessment of the root causes of PTS related problems, and regional capacity to manage these problems;

5. Identification of regional priority PTS related environmental issues; and

6. Identification of PTS related priority environmental issues at the global level.

The outcome of this project will be a scientific assessment of the threats posed by persistent toxic substances to

the environment and human health. The activities undertaken in this project comprise an evaluation of the

sources of persistent toxic substances, their levels in the environment and consequent impact on biota and

humans, their modes of transport over a range of distances, the existing alternatives to their use and remediation

options, as well as the barriers that prevent their good management.

1

1.2 METHODOLOGY

1.2.1 Regional Divisions

To achieve these results, the globe was divided into 12 regions namely: Arctic, North America, Europe,

Mediterranean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indian Ocean, Central and North East Asia (Western North Pacific), South

East Asia and South Pacific, Pacific Islands, Central America and the Caribbean, Eastern and Western South

America, Antarctica. The twelve regions were selected based on obtaining geographical consistency while

trying to reside within financial constraints.

1.2.2 Management Structure

The project is directed by a project manager who is situated at UNEP Chemicals in Geneva, Switzerland. A

Steering Group comprising of representatives of other relevant intergovernmental organisations along with

participation from industry and the non-governmental community was established to monitor the progress of

the project and provide direction for the project manager. Each region was controlled by a regional coordinator

assisted by a team of approximately 4 persons. The co-ordinator and the regional team were responsible for

promoting the project, the collection of data at the national level and to carry out a series of technical and

priority setting workshops for analysing the data on PTS on a regional basis. Besides the 12 POPs from the

Stockholm Convention, the regional team selected the chemicals to be assessed for its region with selection

open for review during the various workshops undertaken throughout the assessment process. Each team wrote

the regional report for the respective region.

1.2.3 Data Processing

Data was collected on sources, environmental concentrations, human and ecological effects through

questionnaires that were filled at the national level. The results from this data collection along with

presentations from regional experts at the technical workshops, were used to develop regional reports on the

PTS selected for analysis. A priority setting workshop with participation from representatives from each

country resulted in priorities being established regarding the threats and damages of these substances to each

region. The information and conclusions derived from the 12 regional reports will be used to develop a global

report on the state of these PTS in the environment.

The project is not intended to generate new information but to rely on existing data and its assessment to arrive

at priorities for these substances. The establishment of a broad and wide- ranging network of participants

involving all sectors of society was used for data collection and subsequent evaluation. Close cooperation with

other intergovernmental organizations such as UNECE, WHO, FAO, UNPD, World Bank and others was

obtained. Most had representatives on the Steering Group Committee that monitored the progress of the

project and critically reviewed its implementation. Contributions were garnered from UNEP focal points,

UNEP POPs focal points, national focal points selected by the regional teams, industry, government agencies,

research scientists and NGOs.

1.2.4 Project Funding

The project cost approximately US$4.2 million funded mainly by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) with

additional sponsorship from countries including Australia, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the

USA. The project started in September, 2000 and is expected to end in April, 2003 with the intention that the

reports be presented to the first meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention

projected for 2003/4.

1.3 DEFINITIONS OF PTS CHEMICALS

The chemicals included in this review were the 12 chemicals covered under the Stockholm Convention on

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), plus several other PTS chemicals. The 12 POPs are aldrin, chlordane,

DDT, dieldrin, dioxins and furans, endrin, hexachlorobenzene, heptachlor, mirex, polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs) and toxaphene. Information was also obtained on endosulphan, hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCH) ,

phthalate esters, polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pentachlorophenol, and organolead, organotin and

organomercury compounds.

Other chemicals considered for inclusion in the survey were, atrazine, chlordecone, hexabromobiphenyl,

polybrominated biphenyl ethers, chlorinated paraffins, octylphenols, and nonylphenols. No data was found for

2

any of these chemicals, although this does not preclude their existence within the region. The potential for this

and the need for appropriate regional investigations, are discussed later in this report.

Definitions of each of the chemicals considered in the report are give below.

1.3.1 - Pesticides

1.3.1.1 Aldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-1,4,4a,5,8,8a-hexahydro-1,4-endo,exo-5,8-dimethanonaphthalene

(C12H8Cl6). CAS Number: 309-00-2

Properties: Solubility in water: 27 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 5.17-

7.4.

Discovery/Uses: It has been manufactured commercially since 1950, and used throughout the world up to the

early 1970s to control soil pests such as corn rootworm, wireworms, rice water weevil, and grasshoppers. It has

also been used to protect wooden structures from termites.

Persistence/Fate: Readily metabolized to dieldrin by both plants and animals. Biodegradation is expected to be

slow and it binds strongly to soil particles, and is resistant to leaching into groundwater. Aldrin was classified

as moderately persistent with half-life in soil and surface waters ranging from 20 days to 1.6 years.

Toxicity: Aldrin is toxic to humans; the lethal dose for an adult has been estimated to be about 80 mg/kg body

weight. The acute oral LD50 in laboratory animals is in the range of 33 mg/kg body weight for guinea pigs to

320 mg/kg body weight for hamsters. The toxicity of aldrin to aquatic organisms is quite variable, with aquatic

insects being the most sensitive group of invertebrates. The 96-h LC50 values range from 1-200 µg/L for

insects, and from 2.2-53 µg/L for fish. The maximum residue limits in food recommended by FAO/WHO

varies from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat to 0.2 mg/kg meat fat. Water quality criteria between 0.1 to 180 µg/L have

been published.

1.3.1.2 Dieldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydroexo-1,4-endo-5,8-

dimethanonaphthalene (C12H8Cl6O). CAS Number: 60-57-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 140 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.78 x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

3.69-6.2.Discovery/Uses: It appeared in 1948 after World War II and used mainly for the control of soil insects

such as corn rootworms, wireworms and catworms.

Persistence/Fate: It is highly persistent in soils, with a half-life of 3-4 years in temperate climates, and

bioconcentrates in organisms. The persistence in air has been estimated in 4-40 hrs.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity for fish is high (LC50 between 1.1 and 41 mg/L) and moderate for mammals (LD50

in mouse and rat ranging from 40 to 70 mg/kg body weight). However, a daily administration of 0.6 mg/kg to

rabbits adversely affected the survival rate. Aldrin and dieldrin mainly affect the central nervous system but

there is no direct evidence that they cause cancer in humans. The maximum residue limits in food

recommended by FAO/WHO varies from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat and 0.2 mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality

criteria between 0.1 to 18 µg/L have been published.

1.3.1.3 Endrin

Chemical Name: 3,4,5,6,9,9-Hexachloro-1a,2,2a,3,6,6a,7,7a-octahydro-2,7:3,6-dimethanonaphth[2,3-b]oxi-

rene (C12H8Cl6O). CAS Number: 72-20-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 220-260 µg/L at 25 °C; vapour pressure: 2.7 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW:

3.21-5.34Discovery/Uses: It has been used since the 50s against a wide range of agricultural pests, mostly on

cotton but also on rice, sugar cane, maize and other crops. It has also been used as a rodenticide.

Persistence/Fate: Is highly persistent in soils (half-lives of up to 12 years have been reported in some cases).

Bioconcentration factors of 14 to 18,000 have been recorded in fish, after continuous exposure.

Toxicity: Endrin is very toxic to fish, aquatic invertebrates and phytoplankton; the LC50 values are mostly less

than 1 µg/L. The acute toxicity is high in laboratory animals, with LD50 values of 3-43 mg/kg, and a dermal

LD50 of 5-20 mg/kg in rats. Long term toxicity in the rat has been studied over two years and a NOEL of 0.05

mg/kg bw/day was found.

3

1.3.1.4 Chlordane

Chemical Name: 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-2,3,3a,4,7,7a-hexahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H6Cl8). CAS

Number: 57-74-9

Properties: Solubility in water: 56 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.98 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25 °C; log KOW: 4.58-

5.57.

Discovery/Uses: Chlordane appeared in 1945 and was used primarily as an insecticide for control of

cockroaches, ants, termites, and other household pests. Technical chlordane is a mixture of at least 120

compounds. Of these, 60-75% are chlordane isomers, the remainder being related to endo-compounds including

heptachlor, nonachlor, diels-alder adduct of cyclopentadiene and penta/hexa/octachlorocyclopentadienes.

Persistence/Fate: Chlordane is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of about 4 years. Its persistence and

high partition coefficient promotes binding to aquatic sediments and bioconcentration in organisms.

Toxicity: LC50 from 0.4 mg/L (pink shrimp) to 90 mg/L (rainbow trout) have been reported for aquatic

organisms. The acute toxicity for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 200-590 mg/kg body weight

(19.1 mg/kg body weight for oxychlordane). The maximum residue limits for chlordane in food are, according

to FAO/WHO between 0.002 mg/kg milk fat and 0.5 mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality criteria of 1.5 to 6 µg/L

have been published. Chlordane has been classified as a substance for which there is evidence of endocrine

disruption in an intact organism and possible carcinogenicity to humans.

1.3.1.5 Heptachlor

Chemical Name: 1,4,5,6,7,8,8-Heptachloro-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H5Cl7). CAS

Number: 76-44-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 180 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.4-

5.5.

Production/Uses: Heptachlor is used primarily against soil insects and termites, but also against cotton insects,

grasshoppers, and malaria mosquitoes. Heptachlor epoxide is a more stable breakdown product of heptachlor.

Persistence/Fate: Heptachlor is metabolised in soils, plants and animals to heptachlor epoxide, which is more

stable in biological systems and is carcinogenic. The half-life of heptachlor in soil is in temperate regions 0.75

2 years. Its high partition coefficient provides the necessary conditions for bioconcentrating in organisms.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of heptachlor to mammals is moderate (LD50 values between 40 and 119 mg/kg

have been published). The toxicity to aquatic organisms is higher and LC50 values down to 0.11 µg/L have been

found for pink shrimp. Limited information is available on the effects in humans and studies are inconclusive

regarding heptachlor and cancer. The maximum residue levels recommended by FAO/WHO are between 0.006

mg/kg milk fat and 0.2 mg/kg meat or poultry fat.

1.3.1.6 Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)

Chemical Name: 1,1,1-Trichloro-2,2-bis-(4-chlorophenyl)-ethane (C14H9Cl5). CAS Number: 50-29-3.

Properties: Solubility in water: 1.2-5.5 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.2 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

6.19 for pp'-DDT, 5.5 for pp'-DDD and 5.7 for pp'-DDE.

Discovery/Use: DDT appeared for use during World War II to control insects that spread diseases like malaria,

dengue fever and typhus. Following this, it was widely used on a variety of agricultural crops. The technical

product is a mixture of about 85% pp'-DDT and 15% op'-DDT isomers.

Persistence/Fate: DDT is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of up to 15 years and of 7 days in air. It also

exhibits high bioconcentration factors (in the order of 50000 for fish and 500000 for bivalves). In the

environment, the product is metabolized mainly to DDD and DDE.

Toxicity: The lowest dietary concentration of DDT reported to cause egg shell thinning was 0.6 mg/kg for the

black duck. LC50 of 1.5 mg/L for largemouth bass and 56 mg/L for guppy have been reported. The acute

toxicity of DDT for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 113-118 mg/kg body weight. DDT has been

shown to have an estrogen-like activity, and possible carcinogenic activity in humans. The maximum residue

level in food recommended by WHO/FAO range from 0.02 mg/kg milk fat to 5 mg/kg meat fat. Maximum

permissible DDT residue levels in drinking water (WHO) is 1.0 µg/L.

1.3.1.7 Toxaphene

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated bornanes and camphenes (C10H10Cl8). CAS Number: 8001-35-2

4

Properties: Solubility in water: 550 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW : 3.23-

5.50.

Discovery/Uses: Toxaphene has been in use since 1949 as a nonsystemic insecticide with some acaricidal

activity, primarily on cotton, cereal grains fruits, nuts and vegetables. It was also used to control livestock

ectoparasites such as lice, flies, ticks, mange, and scab mites. The technical product is a complex mixture of

over 300 congeners, containing 67-69% chlorine by weight.

Persistence/Fate: Toxaphene has a half life in soil from 100 days up to 12 years. It has been shown to

bioconcentrate in aquatic organisms (BCF of 4247 in mosquito fish and 76000 in brook trout).

Toxicity: Toxaphene is highly toxic in fish, with 96-hour LC50 values in the range of 1.8 µg/L in rainbow trout

to 22 µg/L in bluegill. Long term exposure to 0.5 µg/L reduced egg viability to zero. The acute oral toxicity is

in the range of 49 mg/kg body weight in dogs to 365 mg/kg in guinea pigs. In long term studies NOEL in rats

was 0.35 mg/kg bw/day, LD50 ranging from 60 to 293 mg/kg bw. For toxaphene exists a strong evidence of the

potential for endocrine disruption. Toxaphene is carcinogenic in mice and rats and is of carcinogenic risk to

humans, with a cancer potency factor of 1.1 mg/kg/day for oral exposure.

1.3.1.8 Mirex

Chemical Name: 1,1a,2,2a,3,3a,4,5,5a,5b,6-Dodecachloroacta-hydro-1,3,4-metheno-1H-cyclobuta[cd]penta-

lene (C10Cl12). CAS Number: 2385-85-5

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.07 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 3 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW: 5.28.

Discovery/Uses: The use in pesticide formulations started in the mid 1950s largely focused on the control of

ants. It is also a fire retardant for plastics, rubber, paint, paper and electrical goods. Technical grade

preparations of mirex contain 95.19% mirex and 2.58% chlordecone, the rest being unspecified. Mirex is also

used to refer to bait comprising corncob grits, soya bean oil, and mirex.

Persistence/Fate: Mirex is considered to be one of the most stable and persistent pesticides, with a half-life is

soils of up to 10 years. Bioconcentration factors of 2600 and 51400 have been observed in pink shrimp and

fathead minnows, respectively. It is capable of undergoing long-range transport due to its relative volatility

(VPL = 4.76 Pa; H = 52 Pa m 3 /mol).

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of Mirex for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 235 mg/kg and dermal

toxicity in rabbits of 80 mg/kg. Mirex is also toxic to fish and can affect their behaviour (LC50 (96 hr) from 0.2

to 30 mg/L for rainbow trout and bluegill, respectively). Delayed mortality of crustaceans occurred at 1 µg/L

exposure levels. There is evidence of its potential for endocrine disruption and possibly carcinogenic risk to

humans.

1.3.1.9 Hexachlorobenzene (HCB)

Chemical Name: Hexachlorobenzene (C6Cl6) CAS Number: 118-74-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 50 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.09 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.93-

6.42.

Discovery/Uses: It was first introduced in 1945 as fungicide for seed treatments of grain crops, and used to

make fireworks, ammunition, and synthetic rubber. Today it is mainly a by-product in the production of a large

number of chlorinated compounds, particularly lower chlorinated benzenes, solvents and several pesticides.

HCB is emitted to the atmosphere in flue gases generated by waste incineration facilities and metallurgical

industries.

Persistence/Fate: HCB has an estimated half-life in soils of 2.7-5.7 years and of 0.5-4.2 years in air. HCB has

a relatively high bioaccumulation potential and long half-life in biota.

Toxicity: LC50 for fish varies between 50 and 200 µg/L. The acute toxicity of HCB is low with LD50 values of

3.5 mg/g for rats. Mild effects of the [rat] liver have been observed at a daily dose of 0.25 mg HCB/kg bw.

HCB is known to cause liver disease in humans (porphyria cutanea tarda) and has been classified as a possible

carcinogen to humans by IARC.

5

1.3.2 - Industrial compounds

1.3.2.1 Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated biphenyls (C12H(10-n)Cln, where n is within the range of 1-10). CAS Number:

Various (e.g. for Aroclor 1242, CAS No.: 53469-21-9; for Aroclor 1254, CAS No.: 11097-69-1).

Properties: Water solubility decreases with increasing chlorination: 0.01 to 0.0001 µg/L at 25°C; vapour

pressure: 1.6-0.003 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.3-8.26.

Discovery/Uses: PCBs were introduced in 1929 and were manufactured in different countries under various

trade names (e.g., Aroclor, Clophen, Phenoclor). They are chemically stable and heat resistant, and were used

worldwide as transformer and capacitor oils, hydraulic and heat exchange fluids, and lubricating and cutting

oils. Theoretically, a total of 209 possible chlorinated biphenyl congeners exist, but only about 130 of these are

likely to occur in commercial products.

Persistence/Fate: Most PCB congeners, particularly those lacking adjacent unsubstituted positions on the

biphenyl rings (e.g., 2,4,5-, 2,3,5- or 2,3,6-substituted on both rings) are extremely persistent in the

environment. They are estimated to have half-lives ranging from three weeks to two years in air and, with the

exception of mono- and di-chlorobiphenyls, more than six years in aerobic soils and sediments. PCBs also have

extremely long half-lives in adult fish, for example, an eight-year study of eels found that the half-life of

CB153 was more than ten years.

Toxicity: LC50 for the larval stages of rainbow trout is 0.32 µg/L with a NOEL of 0.01 µg/L. The acute toxicity

of PCB in mammals is generally low and LD50 values in rat of 1 g/kg bw. IARC has concluded that PCB are

carcinogenic to laboratory animals and probably also for humans. They have also been classified as substances

for which there is evidence of endocrine disruption in an intact organism.

1.3.3 - Unintended by-products

1.3.3.1 Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs) and Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs)

Chemical Name: PCDDs (C12H(8-n)ClnO2) and PCDFs (C12H(8-n)ClnO) may contain between 1 and 8 chlorine

atoms. Dioxins and furans have 75 and 135 possible positional isomers, respectively. CAS Number: Various

(2,3,7,8-TetraCDD: 1746-01-6; 2,3,7,8-TetraCDF: 51207-31-9).

Properties: Solubility in water: in the range 0.43 0.0002 ng/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2 0.007 x 10-6 mm

Hg at 20°C; log KOW: in the range 6.60 8.20 for tetra- to octa-substituted congeners.

Discovery/Uses: They are by-products resulting from the production of other chemicals and from the low-

temperature combustion and incineration processes. They have no known use.

Persistence/Fate: PCDD/Fs are characterized by their lipophilicity, semi-volatility and resistance to

degradation (half life of TCDD in soil of 10-12 years) and to long-range transport. They are also known for

their ability to bio-concentrate and biomagnify under typical environmental conditions.

Toxicity: The toxicological effects reported refers to the 2,3,7,8-substituted compounds (17 congeners) that

are agonist for the AhR. All the 2,3,7,8-substituted PCDDs and PCDFs plus coplanar PCBs (with no chlorine

substitution at the ortho positions) show the same type of biological and toxic response. Possible effects include

dermal toxicity, immunotoxicity, reproductive effects and teratogenicity, endocrine disruption and

carcinogenicity. At the present time, the only persistent effect associated with dioxin exposure in humans is

chloracne. The most sensitive groups are fetus and neonatal infants.

Effects on the immune systems in the mouse have been found at doses of 10 ng/kg bw/day, while reproductive

effects were seen in rhesus monkeys at 1-2 ng/kg bw/day. Biochemical effects have been seen in rats down to

0.1 ng/kg bw/day. In a re-evaluation of the TDI for dioxins, furans (and planar PCB), the WHO decided to

recommend a range of 1-4 TEQ pg/kg bw, although more recently the acceptable intake value has been set

monthly at 1-70 TEQ pg/kg bw.

1.3.4 - Regional specific

1.3.4.1 Hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCH)

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,5,6-Hexachlorocyclohexane (mixed isomers) (C6H6Cl6). CAS Number: 608-73-1 (-

HCH, lindane: 58-89-9).

6

Properties: -HCH: solubility in water: 7 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

3.8.

Discovery/Uses: There are two principle formulations: "technical HCH", which is a mixture of various

isomers, including -HCH (55-80%), -HCH (5-14%) and -HCH (8-15%), and "lindane", which is essentially

pure -HCH. Historically, lindane was one of the most widely used insecticides in the world. Its insecticidal

properties were discovered in the early 1940s. It controls a wide range of sucking and chewing insects and has

been used for seed treatment and soil application, in household biocidal products, and as textile and wood

preservatives.

Persistence/Fate: Lindane and other HCH isomers are relatively persistent in soils and water, with half lives

generally greater than 1 and 2 years, respectively. HCH are much less bioaccumulative than other

organochlorines because of their relatively low liphophilicity. On the contrary, their relatively high vapor

pressures, particularly of the -HCH isomer, determine their long-range transport in the atmosphere.

Toxicity: Lindane is moderately toxic for invertebrates and fish, with LC50 values of 20-90 µg/L. The acute

toxicity for mice and rats is moderate with LD50 values in the range of 60-250 mg/kg. Lindane resulted to have

no mutagenic potential in a number of studies but an endocrine disrupting activity.

1.3.4.2 Endosulfan

Chemical Name: 6,7,8,9,10,10-Hexachloro-1,5,5a,6,9,9a-hexahydro-6,9-methano-2,4,3-benzodioxathiepin-3-

oxide (C9H6Cl6O3S). CAS Number: 115-29-7.

Properties: Solubility in water: 320 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.17 x 10-4 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW: 2.23-

3.62.

Discovery/Uses: Endosulfan was first introduced in 1954. It is used as a contact and stomach insecticide and

acaricide in a great number of food and nonfood crops (e.g. tea, vegetables, fruits, tobacco, cotton) and it

controls over 100 different insect pests. Endosulfan formulations are used in commercial agriculture and home

gardening and for wood preservation. The technical product contains at least 94% of two pure isomers, - and

-endosulfan.

Persistence/Fate: It is moderately persistent in the soil environment with a reported average field half-life of

50 days. The two isomers have different degradation times in soil (half-lives of 35 and 150 days for - and -

isomers, respectively, in neutral conditions). It has a moderate capacity to adsorb to soils and it is not likely to

leach to groundwater. In plants, endosulfan is rapidly broken down to the corresponding sulfate, on most fruits

and vegetables, 50% of the parent residue is lost within 3 to 7 days.

Toxicity: Endosulfan is highly to moderately toxic to bird species (Mallards: oral LD50 31 - 243 mg/kg) and it

is very toxic to aquatic organisms (96-hour LC50 rainbow trout 1.5 µg/L). It has also shown high toxicity in rats

(oral LD50: 18 - 160 mg/kg, and dermal: 78 - 359 mg/kg). Female rats appear to be 45 times more sensitive to

the lethal effects of technical-grade endosulfan than male rats. The -isomer is considered to be more toxic than

the -isomer. There is a strong evidence of its potential for endocrine disruption.

1.3.4.3 Pentachlorophenol (PCP)

Chemical Name: Pentachlorophenol (C6Cl5OH). CAS Number: 87-86-5.

Properties: Solubility in water: 14 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 16 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.32

5.86.

Discovery/Uses: It is used as insecticide (termiticide), fungicide, non-selective contact herbicide (defoliant)

and, particularly as wood preservative. It is also used in anti-fouling paints and other materials (e.g. textiles,

inks, paints, disinfectants and cleaners) as inhibitor of fermentation. Technical PCP contains trace amounts of

PCDDs and PCDFs

Persistence/Fate: The rate of photodecomposition increases with pH (t1/2 100 hr at pH 3.3 and 3.5 hr at pH

7.3). Complete decomposition in soil suspensions takes >72 days, other authors reports half-life in soils of 23-

178 days. Although enriched through the food chain, it is rapidly eliminated after discontinuing the exposure

(t

1/2 = 10-24 h for fish).

Toxicity: It has been proved to be acutely toxic to aquatic organisms and have certain effects on human health,

at the time that exhibits off-flavour effects at very low concentrations. The 24-h LC50 values for trout were

reported as 0.2 mg/L, and chronic toxicity effects were observed at concentrations down to 3.2 µg/L.

Mammalian acute toxicity of PCP is moderate-high. LD50 oral in rat ranging from 50 to 210 mg/kg bw have

7

been reported. LC50 ranged from 0.093 mg/L in rainbow trout (48 h) to 0.77-0.97 mg/L for guppy (96 h) and

0.47 mg/L for fathead minnow (48 h).

1.3.4.4 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)

Chemical Name: PAHs is a group of compounds consisting of two or more fused aromatic rings. CAS

Number:

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.00014 -2.1 mg/L at 25ºC; vapour pressure: from 0.0015 x 10-9 to 0.0051

mmHg at 25°C; log KOW: 4.79-8.20

Discovery/Use: Most of these are formed during incomplete combustion of organic material and the

composition of PAHs mixture vary with the source(s) and also due to selective weathering effects in the

environment.

Persistence/Fate: Persistence of the PAHs varies with their molecular weight. The low molecular weight

PAHs are most easily degraded. The reported half-lives of naphthalene, anthracene and benzo(e)pyrene in

sediment are 9, 43 and 83 hours, respectively, whereas for higher molecular weight PAHs, their half-lives are

up to several years in soils/sediments. The BCFs in aquatic organisms frequently range between 100-2000 and

it increases with increasing molecular size. Due to their wide distribution, the environmental pollution by PAHs

has aroused global concern.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of low PAHs is moderate with an LD50 of naphthalene and anthracene in rat of 490

and 18000 mg/kg body weight respectively, whereas the higher PAHs exhibit higher toxicity and LD50 of

benzo(a)anthracene in mice is 10mg/kg body weight. In Daphnia pulex, LC50 for naphthalene is 1.0 mg/L, for

phenanthrene 0.1 mg/L and for benzo(a)pyrene is 0.005 mg/L. The critical effect of many PAHs in mammals is

their carcinogenic potential. The metabolic action of these substances produce intermediates that bind

covalently with cellular DNA. IARC has classified benz[a]anthracene, benzo[a]pyrene, and

dibenzo[a,h]anthracene as probable carcinogenic to humans. Benzo[b]fluoranthene and indeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene

were classified as possible carcinogens to humans.

1.3.4.5 Phthalates

Chemical Name: They encompass a wide family of compounds. Dimethylphthalate (DMP), diethylphthalate

(DEP), dibutylphthalate (DBP), benzylbutylphthalate (BBP), di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)(C24H38O4) and

dioctylphthalate (DOP) are some of the most common. CAS Nos.: 84-74-2 (DBP), 85-68-7 (BBP), 117-81-7

(DEHP).

Properties: The physico-chemical properties of phthalic acid esters vary greatly depending on the alcohol

moieties. Solubility in water: 9.9 mg/L (DBP) and 0.3 mg/L (DEHP) at 25°C; vapour pressure: 3.5 x 10-5

(DBP) and 6.4 x 10-6 (DEHP) mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW: 1.5 to 7.1.

Discovery/Uses: They are widely used as plasticisers, insect repellents, solvents for cellulose acetate in the

manufacture of varnishes and dopes. Vinyl plastic may contain up to 40% DEHP.

Persistence/fate: They have become ubiquitous pollutants, in marine, estuarine and freshwater sediments,

sewage sludges, soils and food. Degradation (t1/2) values generally range from 1-30 days in soils and

freshwaters.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of phthalates is usually low: the oral LD50 for DEHP is about 25-34 g/kg,

depending on the species; for DBP reported LD50 values following oral administration to rats range from 8 to

20 g/kg body weight; in mice, values are approximately 5 to 16 g/kg body weight. In general, DEHP is not

toxic for aquatic communities at the low levels usually present. In animals, high levels of DEHP damaged the

liver and kidney and affected the ability to reproduce. There is no evidence that DEHP causes cancer in humans

but they have been reported as endocrine disrupting chemicals. The EPA proposed a Maximum Admissible

Concentration (MAC) of 6 µg/L of DEHP in drinking water.

1.3.4.6 Organotin compounds

Chemical Name: Organotin compounds comprise mono-, di-, tri- and tetrabutyl and triphenyl tin compounds.

They conform to the following general formula (n-C4H9)nSn-X and (C6H5)3Sn-X, where X is an anion or a

group linked covalently through a hetero-atom. CAS Number: 56-35-9 (TBTO); 76-87-9 (TPTOH)

Properties: Solubility in water: 4 mg/L (TBTO) and 1 mg/L (TPTOH) at 25°C and pH 7; vapour pressure: 7.5

x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C (TBTO) 3.5 x 10-8 mmHg at 50ºC (TPTOH); log KOW: 3.19 - 3.84. In sea water and

under normal conditions, TBT exists as three species in seawater (hydroxide, chloride, and carbonate).

8

Discovery/Uses: They are mainly used as antifouling paints (tributyl and triphenyl tin) for underwater

structures and ships. Minor identified applications are as antiseptic or disinfecting agents in textiles and

industrial water systems, such as cooling tower and refrigeration water systems, wood pulp and paper mill

systems, and breweries. They are also used as stabilizers in plastics and as catalytic agents in soft foam

production. It is also used to control the shistosomiasis in various parts of the world.

Persistence/Fate: Under aerobic conditions, TBT takes 1 to 3 months to degrade, but in anaerobic soils may

persist for more than 2 years. Because of the low water solubility it binds strongly to suspended material and

sediments. TBT is lipophilic and tends to accumulate in aquatic organisms. Oysters exposed to very low

concentrations exhibit BCF values from 1000 to 6000.

Toxicity: TBT is moderately toxic and all breakdown products are even less toxic. Its impact on the

environment was discovered in the early 1980s in France with harmful effects in aquatic organisms, such as

shell malformations of oysters, imposex in marine snails and reduced resistance to infection (e.g. in flounder).

Molluscs react adversely to very low levels of TBT (0.06-2.3 ug/L). Lobster larvae show a nearly complete

cessation of growth at just 1.0 ug/L TBT. In laboratory tests, reproduction was inhibited when female snails

exposed to 0.05-0.003 ug/L of TBT developed male characteristics. Large doses of TBT have been shown to

damage the reproductive and central nervous systems, bone structure, and the liver bile duct of mammals.

1.3.4.7 Organomercury compounds

Chemical Name: The main compound of concern is methyl mercury (HgCH3). CAS Number: 22967-92-6

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.1 g/L at 21°C (HgCH3Cl) and 1.0 g/L at 25ºC (Hg(CH3)2); vapour pressure:

8.5 x 10-3 mm Hg at 25°C (HgCH3Cl); log KOW: 1.6 (HgCH3Cl) and 2.28 (Hg(CH3)2).

Production/Uses: There are many sources of mercury release to the environment, both natural (volcanoes,

mercury deposits, and volatilization from the ocean) and human-related (coal combustion, chlorine alkali

processing, waste incineration, and metal processing). It is also used in thermometers, batteries, lamps,

industrial processes, refining, lubrication oils, and dental amalgams. Methyl mercury has no industrial uses; it is

formed in the environment by methylation of the inorganic mercurial ion mainly by microorganisms in the

water and soil.

Persistence/Fate: Mercury released into the environment can either stay close to its source for long periods, or

be widely dispersed on a regional or even world-wide basis. Not only are methylated mercury compounds

toxic, but highly bioaccumulative as well. The increase in mercury as it rises in the aquatic food chain results in

relatively high levels of mercury in fish consumed by humans. Ingested elemental mercury is only 0.01%

absorbed, but methyl mercury is nearly 100% absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. The biological half-life

of mercury is 60 days.

Toxicity: Long-term exposure to either inorganic or organic mercury can permanently damage the brain,

kidneys, and developing fetus. The most sensitive target of low level exposure to metallic and organic mercury

following short or long term exposures appears to be the nervous system.

1.3.4.8 Organolead compounds

Chemical Name: Alkyllead compounds may be confined to tetramethyllead (TML, Pb(CH3)4) and

tetraethyllead (TEL, Pb(C2H5)4). CAS Number: 75-74-1 (TML) and 78-00-2 (TEL).

Properties: Solubility in water: 17.9 mg/L (TML) and 0.29 mg/L (TEL) at 25°C; vapour pressure: 22.5 and

0.15 mm Hg at 20°C for TML and TEL, respectively.

Discovery/Uses: Tetramethyl and tetraethyllead are widely used as "anti-knocking" additives in gasoline. The

release of TML and TEL are drastically reduced with the introduction of unleaded gasoline in late 70's in USA

and followed by other parts of the world. However, leaded gasoline is still available which contribute to the

emission of TEL and to a less extent TML to the environment.

Persistence/Fate: Under environmental conditions such as in air or in aqueous solution, dealkylation occurs to

produce the less alkylated forms and finally to inorganic lead. However, there is limited evidence that under

some circumstances, natural methylation of lead salts may occur. Minimal bioaccumulations were observed for

TEL in shrimps (650x), mussels (120x) and plaice (130x) and for TML in shrimps (20x) , mussels (170x), and

plaice (60x).

Toxicity: Lead and lead compounds has been found to cause cancer in the respiratory and digestive systems of

workers in lead battery and smelter plants. However, tetra-alkyllead compounds have not been sufficiently

tested for the evidence of carcinogenicity. Acute toxicity of TEL and TML are moderate in mammals and high

9

for aquatic biota. LD50 (rat, oral) for TEL is 35 mg Pb/kg and 108 mg Pb/kg for TML. LC50 (fish, 96hrs) for

TEL is 0.02 mg/kg and for TML is 0.11 mg/kg.

1.4 DEFINITION OF THE PACIFIC REGION

For the purposes of this report the Pacific Region was taken as the area between latitudes 23° N and 23° S of

the Equator and between longitudes 130° W and 120° E. of the International Dateline. It covers over 30 million

square kilometers of the Earth's surface, spreading from the Northern Marianas and Palau in the Northwest to

Pitcairn Islands in the Southeast. Papua New Guinea, the largest of the Pacific Island countries was not

included as part of the Region, although some of the data from that country has been included in the report for

comparative purposes. The region includes the 22 countries and territories listed in the table below, together

with the type of government operating in each:

Table 1.1: Countries and Territories Included in the Region

Countries

Type of Government

Countries

Type of Government

American Samoa

US territory

Northern Mariana Islands Self-governing

Cook Islands

Self-governing state

Palau

US compact association

Federated States of

Federation with US

Pitcairn Islands

British territory

Micronesia

compact of association

Fiji

Independent state

Samoa

Independent state

French Polynesia

French territory

Solomon Islands

Independent state

Guam

US territory

Tokelau

New Zealand territory

Kiribati Republic Tonga Kingdom

Marshall Islands

Republic with US

Tuvalu Independent

state

compact of association

Nauru Republic

Vanuatu

Independent Republic

New Caledonia

French territory

Wallis and Futuna

French territory

Niue Independant

state

Other1 US

territories

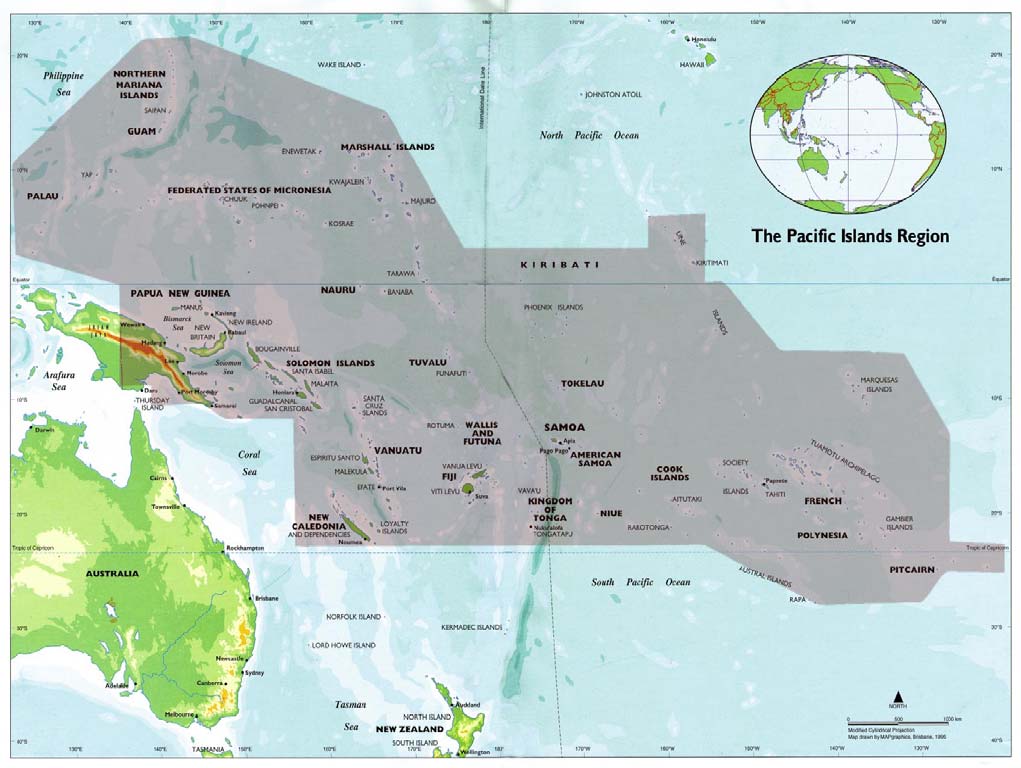

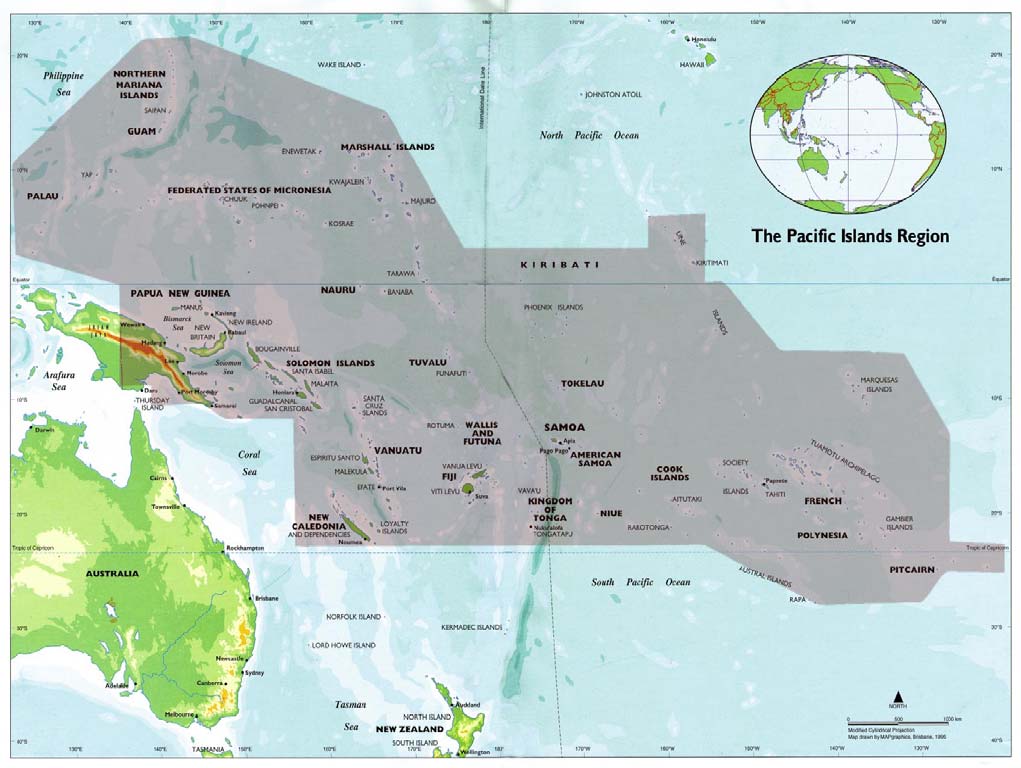

A map of the Pacific Islands region is given in Figure 1.

1.5 PHYSICAL SETTING

1.5.1 Regional Diversity

The Pacific Islands region is very diverse, and encompasses a wide variety of geographical features,

populations, cultures, economies and politics within its 22 Island countries. Most of the countries were

colonized until recently, and this has had lasting effects on the social, cultural, political and economic and

development status of each island state. The Pacific Islands often are considered as covering three sub-regions;

Melanesia (west), Polynesia (southeast) and Micronesia (north), based on their ethnic, linguistic and cultural

differences. The physical sizes, economic prospects, available natural resources and political developments

within these sub-regions suggest that the groupings are still useful, although not necessarily ethnically correct.

1.5.2 The role of the ocean

Spread over an area of 30 million square kilometers, more than 98 per cent of which consists of ocean, the

Pacific region is vast. This area is three times larger than either the USA or China. Of its 7500 islands, only

about 500 are inhabited. This isolation complicates administration, communication, marketing and export of

agricultural and fishing products and the provision of basic services in health, education and training. The

ocean, however, has played a positive role as a natural barrier against the spread of human and plant diseases

and pests, even though this situation is changing fast with modern communication and transport. The size of

the ocean, coupled with the spread of small islands proves to be of large economic value for fisheries

development, particularly because of the EEZs and the sale of fishing rights to DWFNs (Distant-Water Fishing

Nations) for the large Pacific tuna resource.

1

Johnston Atoll, Midway Island, Wake Island, Jarvis and Palmyra

10

The importance of the aquatic environment to the people of the Pacific cannot be overstated. The ocean is a

primary source of food and revenue for most nations in the region, and it is important that this not be adversely

affected by chemical contaminants.

Figure 1.: Map of the Pacific Islands

(The area shaded in grey is the region covered by the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme)

1.5.3 Geographical Variations: High Islands and Low Atolls