CERMES Technical Report No 11

Socio-economic profile of fisheries in the

Grenadine Islands

DAVID GILL, PATRICK McCONNEY AND ROBIN MAHON

Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES)

University of the West Indies, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences,

Cave Hill Campus, Barbados

2007

ABSTRACT

Socio-economic profile of fisheries in the Grenadines

DAVID GILL, PATRICK McCONNEY AND ROBIN MAHON

For proper and effective management of fisheries, there is a need to understand not only their

biophysical environment but also their demographic and socio-economic environment and

dynamics. From June to August 2006, students from the Centre for Resource Management

and Environmental Studies (CERMES) embarked on a trans-boundary socio-economic and

livelihood assessment of fisheries in the Grenadines. The study was divided into two stages

and took place in the Vincentian islands of Bequia, Mustique, Canouan, Mayreau and Union

Island and the Grenadian islands of Petit Martinique and Carriacou. The goal of the first stage

was to create a basic demographic profile of the fishers and to gather data on their gear and

resource-use patterns. This was done through extensive interviews at all of the major fishing

villages in the Grenadines. During this stage 267 fishers were interviewed.

The second phase of this project aimed to create a more detailed socio-economic profile of

the fisheries. This stage involved acquiring more detail on temporal and spatial features of

fishing practices, information on the market orientation of the fishers, revenue, expenditures

and material style of life. Over 75% of the fishers interviewed in the study rely on fishing as

their major income source and less than half have an alternative livelihood. Due to lack of a

reliable source of income, many continue to fish well beyond retirement age. This suggests a

possible vulnerability within the fishing community, especially within the older population.

Shallow-shelf demersals are the most important species group and also the most

overexploited and thus the governments should look to encourage fishers into other fisheries

through market incentives, training and loans. The information from this study will help

resource managers better understand the social and economic factors that affect the fisheries

and may lead to more sustainable and informed decision making. Sectoral and regional

linkages need to be strengthened so as to ensure that the industry goes forward sustainably.

Keywords: demographic, fisheries, Grenadines, socio-economic

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to all who supported me throughout this study:

To God for His goodness and mercy

To my supervisors Dr. McConney and Dr. Robin Mahon for their guidance and patience

To my family and friends for their support. To my team-mate Tanya. To Jean, Kim, Donna,

Kali & Diane for all your help

To the many fishers, fisheries officers and others in the Grenadines for their cooperation and

readiness to share their experiences without whose help, this study would not have been a

success

ii

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................II

1

INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 1

1.1

SUSTAINABLE GRENADINES PROJECT (SUSGREN)................................................................................ 1

1.2

MARINE SPACE USE INFORMATION SYSTEM (MARSIS) ....................................................................... 1

1.3

PROJECT OBJECTIVES............................................................................................................................ 2

1.4

SOCIO-ECONOMIC MONITORING (SOCMON) AS RESEARCH APPROACH................................................. 2

1.5

REPORT OUTLINE.................................................................................................................................. 3

2

METHODOLOGY...................................................................................................................................... 3

2.1

PREPARATORY ACTIVITIES, PLANNING AND RECONNAISSANCE ............................................................ 3

2.2 ...................................................................................................................................................................... 3

2.3

FIELD DATA COLLECTION: SAMPLING METHODOLOGY ......................................................................... 4

2.3.1

Phase I: Rapid initial survey........................................................................................................... 6

2.3.2

Phase II: In-depth survey................................................................................................................ 6

2.4

ANALYSIS, INTERPRETATION AND VALIDATION.................................................................................... 6

3

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: STUDY AREA ..................................................................................... 7

3.1

GEOGRAPHY......................................................................................................................................... 7

3.1.1

Natural threats: Hurricanes ........................................................................................................... 8

3.1.2

Society and economy....................................................................................................................... 8

3.1.3

Marine Protected and Conservation Areas .................................................................................... 9

3.2

ISLAND PROFILES.................................................................................................................................. 9

3.2.1

Bequia............................................................................................................................................. 9

3.2.2

Canouan........................................................................................................................................ 10

3.2.3

Carriacou...................................................................................................................................... 10

3.2.4

Mayreau........................................................................................................................................ 10

3.2.5

Mustique ....................................................................................................................................... 11

3.2.6

Petite Martinique .......................................................................................................................... 11

3.2.7

Union Island ................................................................................................................................. 11

3.3

FISHERIES INFRASTRUCTURE.............................................................................................................. 12

3.3.1

Canouan Fisheries Complex......................................................................................................... 12

3.3.2

Clifton Fisheries Complex, Union Island ..................................................................................... 12

3.3.3

Paget Farm Fishing Complex, Bequia.......................................................................................... 13

3.3.4

Lobster Storage Facilities, Bequia ............................................................................................... 13

3.3.5

Mustique Fishing Complex, Mustique .......................................................................................... 13

3.4

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF FISHING .......................................................................................... 13

3.4.1

Grenada and its Grenadines......................................................................................................... 13

3.4.2

St. Vincent and its Grenadines...................................................................................................... 14

3.5

CURRENT STATUS OF FISHING IN THE GRENADINES............................................................................ 15

3.5.1

Data limitations ............................................................................................................................ 15

3.5.2

Economic value............................................................................................................................. 15

3.5.3

Trading vessels ............................................................................................................................. 16

3.5.4

European Union ban and quality control ..................................................................................... 16

3.6

FISHERIES MANAGEMENT ................................................................................................................... 17

3.6.1

Fished species............................................................................................................................... 17

3.6.2

Legislation and current management measures ........................................................................... 17

3.6.3

Species and gear regulations........................................................................................................ 18

3.7

FISHING TECHNIQUES ......................................................................................................................... 19

3.7.1

Handlining .................................................................................................................................... 19

3.7.2

Traps............................................................................................................................................. 19

3.7.3

Trolling ......................................................................................................................................... 19

3.7.4

Seine net fishing............................................................................................................................ 19

3.7.5

Gill and trammel nets ................................................................................................................... 20

3.7.6

Longlining/Palang ........................................................................................................................ 20

3.7.7

Diving ........................................................................................................................................... 20

3.8

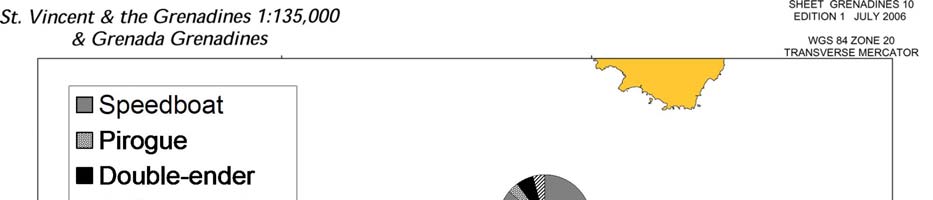

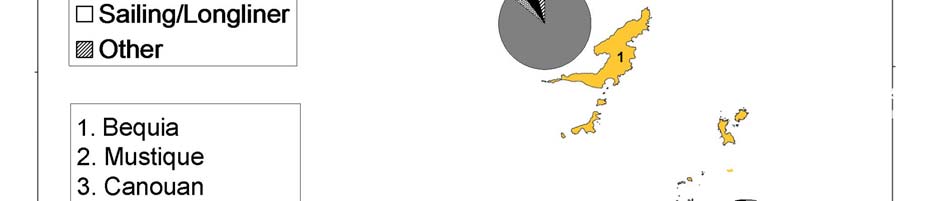

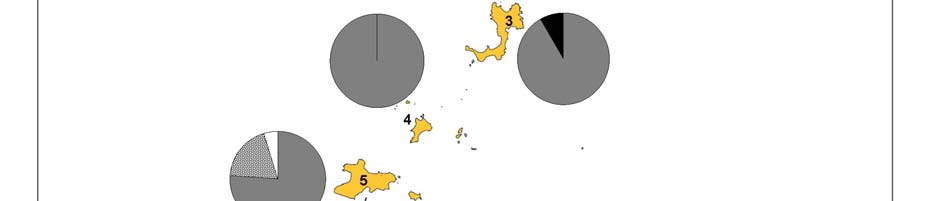

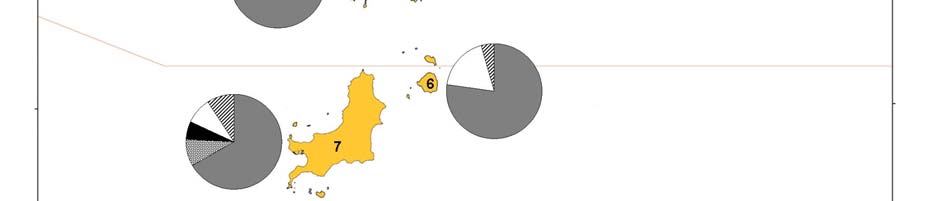

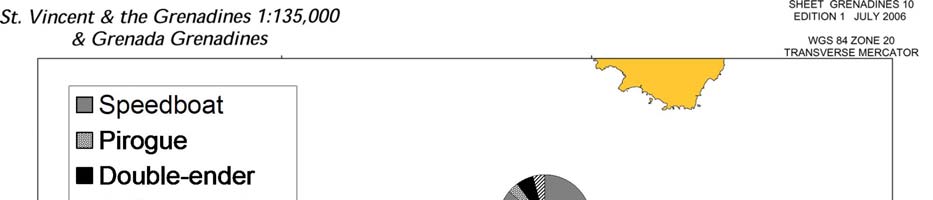

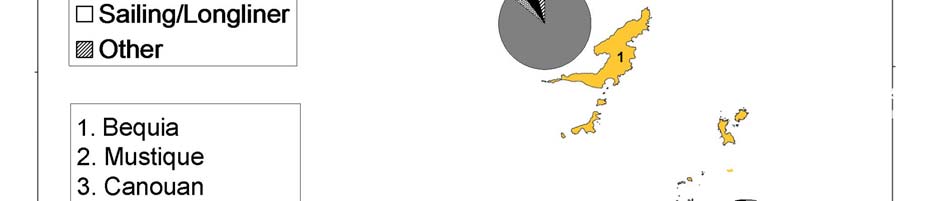

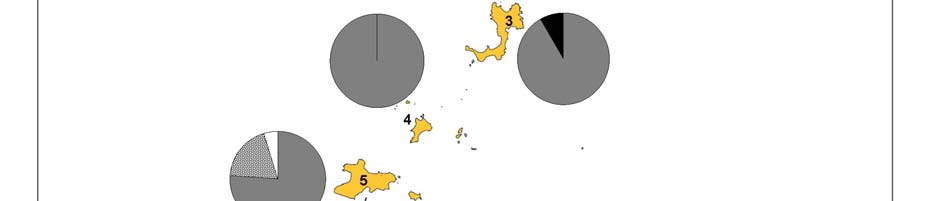

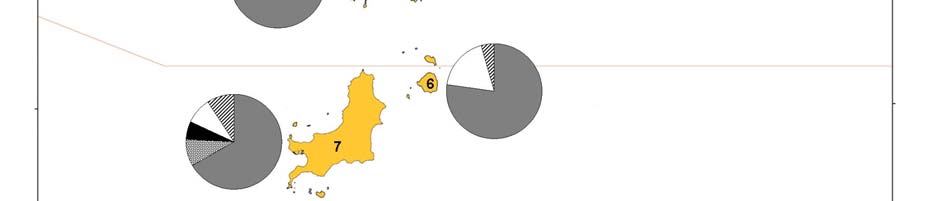

BOAT TYPES ....................................................................................................................................... 20

4

RAPID INITIAL SURVEY (PHASE I): RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ........................................... 20

iii

4.1

ALTERATIONS TO SAMPLING DESIGN .................................................................................................. 21

4.2

DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION ............................................................................................................ 21

4.3

DEPENDENCY ON FISHING .................................................................................................................. 22

4.4

BOAT OWNERSHIP .............................................................................................................................. 24

4.4.1

Boat ownership by island.............................................................................................................. 24

4.4.2

Boat ownership, dependency on fishing, and age ......................................................................... 24

4.5

OTHER OCCUPATIONS......................................................................................................................... 25

4.6

BOAT AND ENGINE TYPES ................................................................................................................... 27

4.7

COASTAL AND MARINE RESOURCE USE............................................................................................... 29

4.7.1

Fishing techniques ........................................................................................................................ 29

4.7.2

Fish groups targeted..................................................................................................................... 32

4.7.3

Areas fished .................................................................................................................................. 34

5

IN-DEPTH SURVEY (PHASE II): RESULTS AND DISCUSSION.................................................... 39

5.1

DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION ............................................................................................................ 39

5.1.1

Education...................................................................................................................................... 40

5.2

HOUSEHOLD COMPOSITION ................................................................................................................ 41

5.3

MATERIAL STYLE OF LIFE................................................................................................................... 41

5.4

OCCUPATIONS AND DEPENDENCY ...................................................................................................... 43

5.5

SHARE SYSTEMS ................................................................................................................................. 44

5.6

CLEANING AND SERVICING................................................................................................................. 44

5.7

COASTAL AND MARINE ACTIVITIES .................................................................................................... 45

5.7.1

Target species ............................................................................................................................... 45

5.7.2

Limitations .................................................................................................................................... 45

5.7.3

Fishing techniques ........................................................................................................................ 47

5.7.4

Fishing intensity............................................................................................................................ 48

5.7.5

Fishing grounds ............................................................................................................................ 49

5.8

FISH MARKETING................................................................................................................................ 50

5.8.1

Demand......................................................................................................................................... 50

5.8.2

Market information by species type .............................................................................................. 50

5.8.3

Market information by buyer ........................................................................................................ 52

5.9

MARKET ORIENTATION BY FISHER PREFERENCE (RELIABILITY, PRICE, CONVENIENCE) ...................... 52

5.9.1

Tourist sector................................................................................................................................ 53

5.10

PHYSICAL CAPITAL............................................................................................................................. 53

5.10.1

Boat and engine ....................................................................................................................... 53

5.10.2

Gear ......................................................................................................................................... 53

5.11

EXPENSES........................................................................................................................................... 54

5.11.1

Trip expenses ........................................................................................................................... 54

5.11.2

Recurrent expenses .................................................................................................................. 54

6

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................................... 55

6.1

DEMOGRAPHICS AND STAKEHOLDER CHARACTERISTICS .................................................................... 55

6.2

RESOURCE USE PATTERNS .................................................................................................................. 55

6.2.1

Demersal fishery........................................................................................................................... 55

6.2.2

Reducing vulnerability.................................................................................................................. 55

6.3

MARKET ATTRIBUTES AND ORIENTATION........................................................................................... 56

6.4

MATERIAL STYLE OF LIFE................................................................................................................... 56

6.5

SECTORAL COORDINATION................................................................................................................. 56

6.6

REGIONAL COORDINATION ................................................................................................................. 57

7

REFERENCES.......................................................................................................................................... 58

8

APPENDICES ........................................................................................................................................... 61

Citation

Gill, D., P. McConney and R. Mahon. 2007. A socio-economic profile of fisheries in the

Grenadine Islands. CERMES Technical Report No. 11. 69pp.

iv

1 INTRODUCTION

Resource management involves balancing conservation with sustainable use (Bunce &

Pomeroy 2003). Resource users have an immense impact on the environment and are the

most vulnerable to its degradation. Managers therefore have to possess an understanding of

the resource use patterns and the socio-economic factors that act upon it (CFRM 2004).

Through interviews with members of the fishing community, this study seeks to create a

socio-economic profile of fishers in the Grenadines. Decision makers can combine

biophysical and socio-economic data to better understand the coastal environmental and the

human interactions and uses that affect it. This information will help to identify coastal areas

that may be at risk of overexploitation and to design appropriate conservation strategies that

will not threaten the livelihoods of the fishermen. It will also aid managers in recognising the

vulnerability of the fishermen to natural and anthropogenic shocks (e.g. hurricanes, market

fluctuations, increased oil prices etc) and to build resilience through informed decision

making. Stakeholder interaction and information gathering enhance local participation in

management and increase the chance of further participation in conservation activities

(Walters et al. 1998). Currently there are various on-going initiatives in the Grenadines to

which this project is supplementary.

1.1 Sustainable Grenadines Project (SusGren)

The goal of the Sustainable Grenadines Project (SusGren) is to assist in the protection of the

social and economic wellbeing of the Grenadine people through the integration of sustainable

development (CERMES 2005). SusGren seeks to build capacity through partnerships with

other civil society organisations and stakeholders providing them with tools to be more

actively involved in managing the resources that they depend heavily on. The information

from this study will help to create an understanding of the socio-economic characteristics of

fishers which is essential to aid SusGren in fulfilling its mandate of promoting sustainable

livelihoods. SusGren commenced this work by hosting a fisherfolk workshop in February

2006 where fishers from around the Grenadines were able to raise and discuss the major

issues affecting the industry (CERMES 2006).

1.2 Marine Space Use Information System (MarSIS)

MarSIS is a computerised Geographic Information System (GIS) which is being created to

amalgamate social, economic, cultural and biophysical resource information & policy to

assist resource managers in effective coastal management (Baldwin 2006). It will identify

critical habitats and areas of concern and conflict amongst marine resource users. This project

aims to combine scientific data with local ecological knowledge to fill information gaps,

promote participation and highlight policy decisions and concerns that should take

precedence. The process began at the planning and data scoping phase in June 2005-May

2006. During this process key informants were identified and support was obtained from the

governments of St. Vincent and the Grenadines and of Grenada. Information for the initial

data scoping was obtained through dialogue with various non-government organisations,

community leaders, key informants and observations at the sites of interest.

At present, data are being collected on all the major marine resource user groups in the

Grenadines. These include day tour operators, dive operators, ferries, and yacht charter

companies. Similar studies have been conducted with the water taxi operators in the

Grenadines (Cooke et al. 2005 and Lizama et al. 2006) and will be compiled with

information from this study to create a marine resource user profile. Key marine habitats,

conservation and management issues, resource use patterns and stakeholder information were

spatially analysed and represented on maps. Subsequent to the data collection, workshops

1

will be held to obtain feedback from stakeholders and government, to identify information

gaps and to plan the next stage of the project.

1.3 Project objectives

The purpose of this project is to acquire socio-economic information on fisheries in the

Grenadines for future use in fisheries and integrated coastal management decision-making.

Specifically, in connection with the SusGren and MarSIS initiatives, this includes the

objectives of collecting information on:

Demographics and stakeholder characteristics: creating a basic demographic profile of

fishers

Resource use patterns: acquiring information on the fishing practices (temporal and

spatial) of fishers in the Grenadines

Market attributes and orientation: gaining an understanding of the market orientation

of the fishers, prices received and patterns by island

Material style of life: acquiring basic information on the income, expenditure and

material style of life of the fishers

This information will provide insight on the location of fishers, what resources they have

available, fishing practices and usage and their perceptions on the resource. This will be made

available to interested parties (government, NGOs, etc) and the spatial socio-economic data

will be used to supplement the attribute data for the MarSIS database (see Section 1.2). The

report will also include recommendations that are suggested by the fishers to improve the

industry.

Although this study involves taking information from stakeholders, it will hopefully facilitate

the creation of a climate of participation amongst the fishers and promote linkages between

the conservation groups, government, scientific communities (e.g. university researchers) and

the fishers. Participatory research methods facilitate stakeholder involvement in the decision

making process by providing a means of input into information to be used for management

decisions. This process allows for community concerns to be aired and resolved and areas of

historical, social and cultural importance to be identified. Through education and

involvement, stakeholders can have a better understanding of the resource and their influence

on it and this process may help to increase support for and participation in management

(Bunce & Pomeroy 2003).

1.4 Socio-economic Monitoring (SocMon) as research approach

The benefits of incorporating local knowledge into resource management are immense.

Collection of data on locations of resources, spatial and temporal information and the use

patterns is an overwhelming task for small Fisheries Divisions in the Caribbean and therefore

they must also rely on the resource users to acquire this information (Walters et al. 1998).

Spatial & temporal information is required to assess the current space-use patterns in the

Grenadines and to develop comprehensive management plans for the area.

A socio-economic assessment is a means to understanding the social, cultural, economic and

political conditions of individuals, groups, communities and organisations (Bunce &

Pomeroy 2003). Fishers play a very important role in coastal resource management as they

directly impact and rely on the sea.

SocMon is a set of guidelines for creating a socio-economic monitoring program at Caribbean

coastal management sites (Bunce & Pomeroy 2003). Using a list of established socio-

economic variables, SocMon allows researchers and managers to help select and prioritise

which variables to include in their analysis, based on the goals and objectives of their project.

2

1.5 Report outline

The next chapter on methodology precedes a description of the study area. The results of

rapid and in-depth surveys are discussed in the fourth chapter. Finally there are conclusions

with recommendations on priority next steps. References are listed and four appendices

provide information on fishes caught and fishing vessels along with copies of the two survey

instruments used.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Preparatory activities, planning and reconnaissance

A modification of the SocMon Caribbean methodology (Bunce & Pomeroy 2003) was

applied in this study. A flow chart outlining the major steps of the process is in Figure 2.1.

Rese

R

ar

ese ch

ar

go

ch

al

go s

al and

a

obj

nd

ect

obj

iv

ect es

iv

Da

D ta scop

ta sc

ing

i

&

&

Second

Seco

ar

nd y

ar da

y

ta

t

a

re

r conn

con ai

a ssan

ss

ce

an

ce

anal

ana ys

y is

Stak

St eho

ak

l

eho der

der

Ident

Iden ificat

i

i

cat on of

n

maj

o

maj r

r

Ident

en ifi

f ca

i ti

t on o

on f

identi

n fic

fi ati

t on

issu

iss es

e and

a

con

nd

cer

con

ns

cer

info

f rm

r a

m tion

o gaps

De

D term

r ination of SocMo

M n vari

r ables

e

De

D te

t rm

r ination of

f

samplin

sam

g d

plin

e

g d si

s gn

Field d

Fiel

a

d d ta

t c

a o

c llecti

lle

o

cti n

Final a

Fina n

l a al

a ys

y is & r

is & e

r port

por i

t ng

Figure 2.1 Flow chart outlining the major phases of the study

During the months of January to June, Ms. Kimberly Baldwin of the Centre for Resource

Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES) conducted an initial scoping of the

marine resource users of the Grenadines (Baldwin 2006). This involved secondary data

collection, interviews with key informants and other stakeholders and general observation of

the study area. Concurrently, secondary data assessment and scoping was also conducted and

the data were compiled so as to identify the information gaps required to complete the

MarSIS database (see Section 1.2). Based on the gaps identified, the objectives of this study

3

were created and the SocMon variables that were utilised in this study were selected. The list

of SocMon Caribbean variables can be found in Table 2.1 in which the ones chosen for this

study are highlighted.

Table 2.1 List of variables in the SocMon Caribbean methodology with selected variables highlighted in

grey

Var. no.

Community or secondary source

Var. no.

Household or individual survey

K1

Study area

S1

Age

K2

Population

S2

Gender

K3 Number

of

households

S3

Ethnicity

K4 Migration

rate

S4

Education

K5 Age

S5

Religion

K6 Gender

S6 Language

K7 Education

S7

Occupation

K8 Literacy

S8 Household

size

K9 Ethnicity

S9

Household income

K10 Religion

S10

Household activities

K11

Language

S11

Household goods and services

K12

Occupation

S12

Types of household uses

K13

Community infrastructure

S13

Household market orientation

K14

Coastal and marine activities

S14

Household uses

K15

Goods/services from marine activities

S15

Non-market and non-use values

K16

Types of use of good/service

S16

Perceptions of resource conditions

K17

Value of goods and services

S17

Perceived threats

K18

Goods/services market orientation

S18

Awareness of rules and regulations

K19

Use patterns

S19

Compliance

K20

Levels and types of impact

S20

Enforcement

K21

Level of use by outsiders

S21

Participation in decision-making

K22

Household use

S22

Membership in stakeholder organisations

K23

Stakeholders

S23

Perceived coastal management problems

K24

Tourist profile

S24

Perceived coastal management solutions

K25

Management body

S25

Perceived community problems

K26

Management plan

S26

Successes in coastal management

K27

Enabling legislation

S27

Challenges in coastal management

K28

Management resources

S28

Material style of life

K29

Formal tenure and rules

[New]

Boat painting and engine servicing

K30

Informal tenure, rules, customs and

[New]

Boat cleaning

traditions

K31 Stakeholder

participation

K32

Community and stakeholder organisations

It must be noted however that this study did not employ the entire SocMon Caribbean

methodology as it was planned as an assessment rather than with the intention of monitoring.

To get an idea of some of the possible environmental impacts of fishing (mainly marine

pollution) and to gather data to be compared with the water taxi study conducted by Lizama

et al. (2005), two new variables were created. To examine these variables, fishers were

questioned on their boat and engine cleaning/maintenance practices.

2.2 Field data collection: Sampling methodology

The study took place between the months of June and August 2006 on 7 of the inhabited

islands of the Vincentian and Grenada Grenadines (see Table 2.2). The design of the

questionnaires followed the methods outlined in the SocMon Caribbean methodology (Bunce

& Pomeroy 2003) and some of the content was adapted from questionnaires created by

4

McConney (2005), Cooke et al. (2005) and Lizama et al. (2005) that were used for other

resource users in the Grenadines.

Table 2.2 Fishing communities/villages in each island that were surveyed during the data collection phase

Island Fishing

Village

St. Vincent and the Grenadines

Port Elizabeth, Lower Bay, La Pompe,

Bequia

Friendship Bay

Paget Farm

Mustique

Mustique Fishing Camp

Grand Bay,Charles Bay

Canouan

Canouan Fisheries Complex

Mayreau

Saline Bay, SaltWhistle Bay

Union Island

Clifton, Ashton

Grenada

Petite Martinique

Sanchez

Hillsborough, Belmont, Windward,

Carriacou

L'Esterre, Paradise Bay, Harvey Vale

The sampling design was a census, similar to the one that was used by Cooke et al. (2005)

and Lizama et al. (2005) where each community was intensely surveyed until no new

respondents were encountered. At the start of the data collection, however, it was evident that

it would be virtually impossible to conduct a census of all the fishers in the Grenadines given

the time and the resources available, and the following limitations: (1) the study took place

out of lobster season, and subsequently, fishers were either engaged in other occupations or

out of the island; (2) some of the fishers were dispersed throughout the islands which would

require a much greater sampling effort and time to interview each household on the island;

and (3) this study focused on persons who depended on fishing for their livelihoods, as

opposed to recreational fishers.

To overcome these limitations, the sampling design of Phase I was restructured from a census

to a saturation sample, where all persons located in and around the major fishing villages and

markets were surveyed, until the interviewers encountered few to no new fishers. Therefore,

the 267 fishers that were identified in the rapid initial survey (Phase I) are in fact an

underestimation in census terms. However this is an adequate sample, estimated at 10-20% of

all fishers based on key informant and secondary data. Because of the methods, limitations

and biases listed above it cannot be claimed that the study sample is statistically

representative, but it is likely that results obtained from it reflect population characteristics to

a large extent.

5

2.2.1 Phase I: Rapid initial survey

This stage involved visiting the major fishing communities and interviewing all the fishers

encountered in the area, totalling 267 fishers. A simple, one page questionnaire (see

Appendix 1) was used to collect:

· Demographic information on the fisher

· Type of fishery he/she is involved in

· Boat and equipment characteristics

· Spatial information on fishing practices

The survey took approximately 3-5 minutes to complete, depending on the details given by

the respondent. In very small, compact fishing villages (e.g. Mustique Fishing Camp,

Mustique), sampling was completed in one day and almost 100% of the fishers in the area

were surveyed. Sampling in large fishing communities such as Paget Farm, Bequia ranged

from 2-4 days to ensure that all available fishers were interviewed.

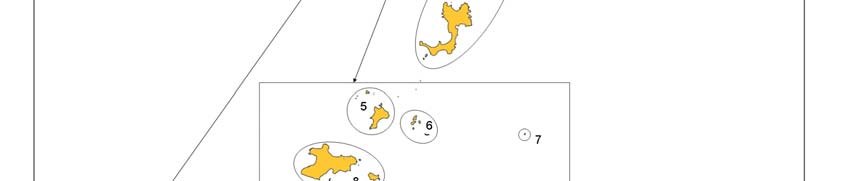

2.2.2 Phase II: In-depth survey

After the initial survey was conducted on each island, the second survey was constructed and

tested on select fishers in the field (n=3). The sampling design of this survey was to use the

initial survey as a sampling frame and re-interview 25-33% of the fisher respondents on each

island visited in the first stage, but without rejecting any new fishers that were encountered

(see Figure 2.2). Another aim was to attempt to involve each type of fisher in the study by

purposely ensuring that the less common types of fishers were included. However, due to the

multiplicity of the types of fishing practiced, it was difficult to distinguish a fisher by a

particular fishing technique. Also as the survey depended on the willingness of individuals to

participate and their level of interest, not all of the data could be collected in each interview.

The surveys conducted in Phase II (see Appendix 2) encountered 64 fishers, most of whom

were encountered during Phase I. The interview took an estimated 15-45 minutes to complete

depending on the detail given by the respondent.

40%

35%

d

30%

e

w

i

e

25%

t

e

r

v

n

s

i

er

Initial Survey

20%

In Depth

i

sh

f

f

15%

t

o

r

cen

e

10%

P

5%

0%

Bequia

Canouan

Carriacou

Mayreau

Mustique

Petite

Union Island

Martinique

Island

Figure 2.2 Proportions of fishers interviewed by island during the initial and in-depth survey

2.3 Analysis, interpretation and validation

After the data were collected, the key informants identified in Baldwin 2006 (mainly fisheries

officers) were consulted to validate the information for their respective islands. The data were

compiled and analysed in Microsoft Excel 2003 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS) version 11.

6

During the month of October, community meetings (comprising of mainly fishers) were held

in each island. The goals of these meetings were to: 1) present information to the community

on MarSIS and the results of this study, 2) conduct a simple fishery resource mapping

exercise and 3) to validate some of the major results of the study.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: STUDY AREA

A major part of any SocMon study is the characterisation of the study area. This provides a

critical background to the physical, social, economic and cultural conditions that affect the

community under examination. Information in this section comprises both secondary data and

results from discussions with key informants and fishers.

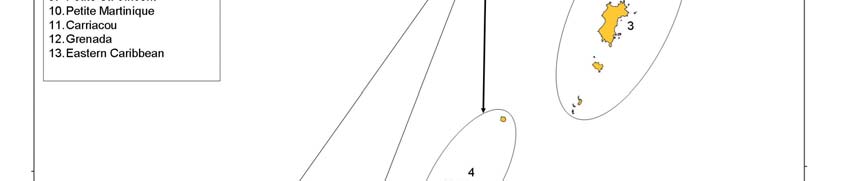

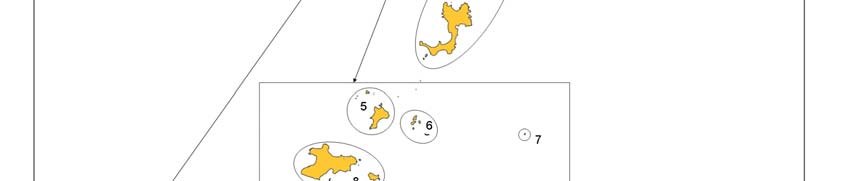

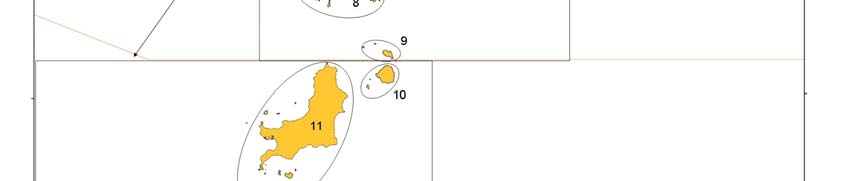

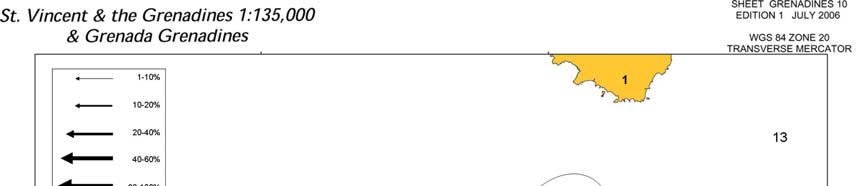

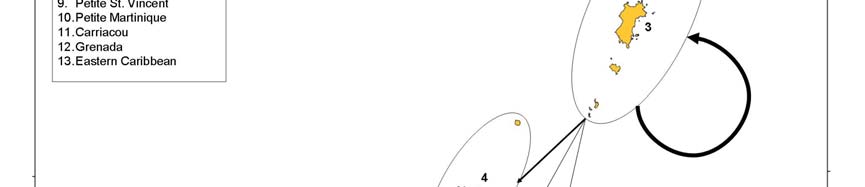

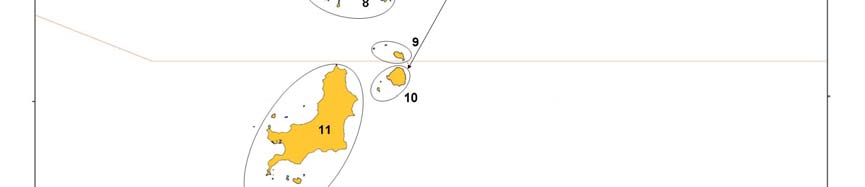

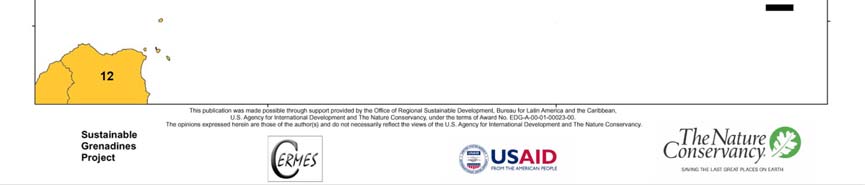

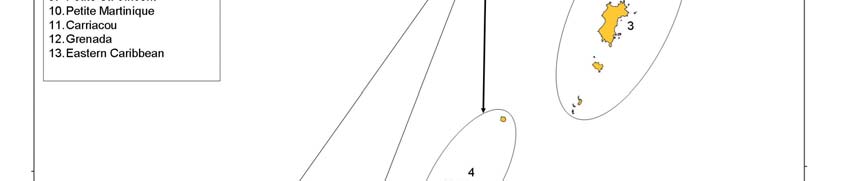

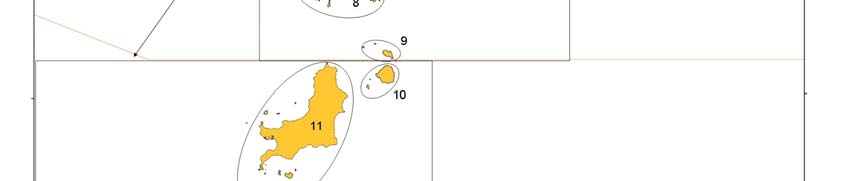

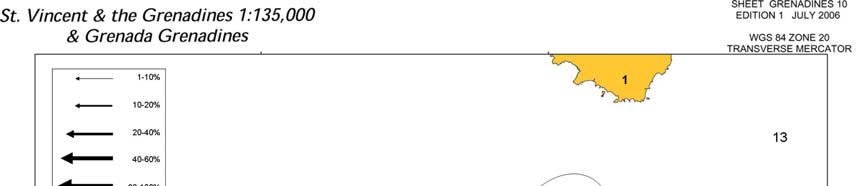

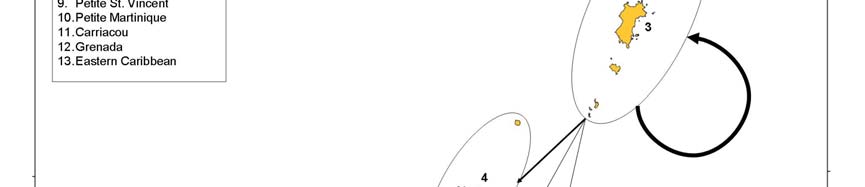

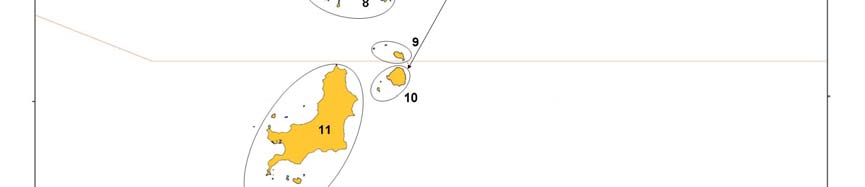

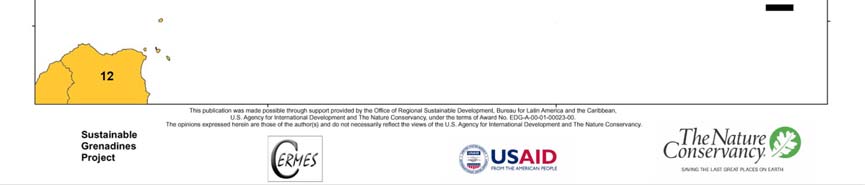

3.1 Geography

The Grenadine islands lie on a shallow bank located between the islands of St. Vincent and

Grenada (see Figure 3.1). Islands north of the boundary belong to St. Vincent and south of

the boundary belong to Grenada. Most of these low lying islands were formed by volcanic

activity associated with Grenada (ECLAC 2004) which created an archipelago consisting of

over 30 islands (CCA/IRF 1991).

o

15

MARTINIQUE

CARIBBEAN

SEA

ST. LUCIA

ST. VINCENT

BARBADOS

ES

E

IN

D

A

EN

E

R

E G

E

TH

T

ATLANTIC

GRENADA

OCEAN

TOBAGO

TRINIDAD

o

10

o

VENEZUELA

60

Boundary

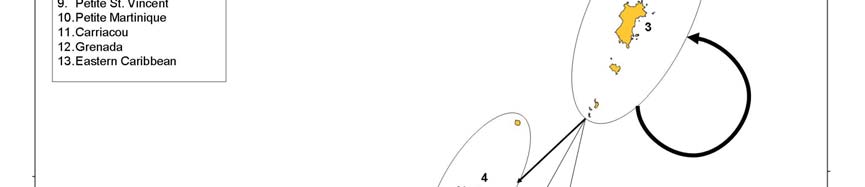

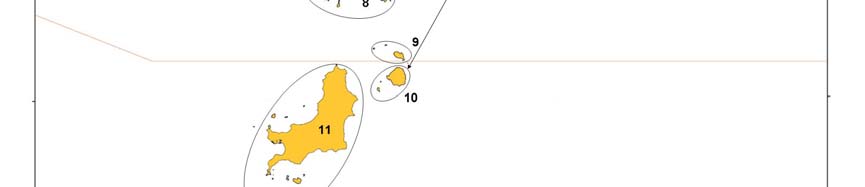

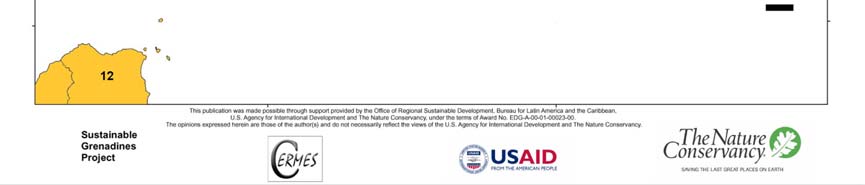

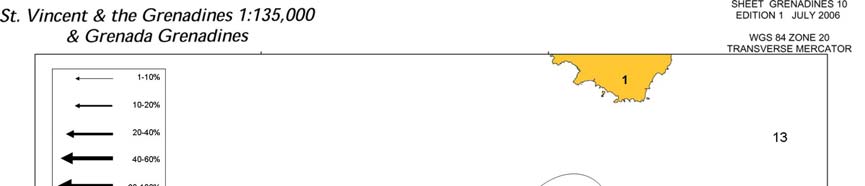

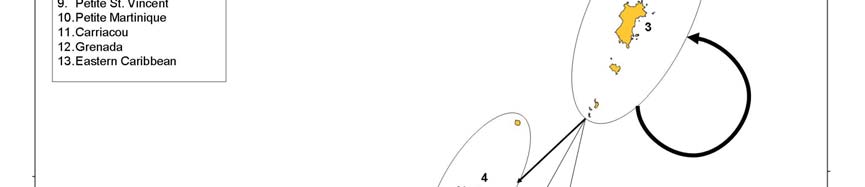

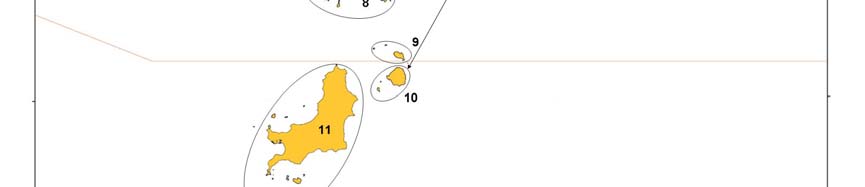

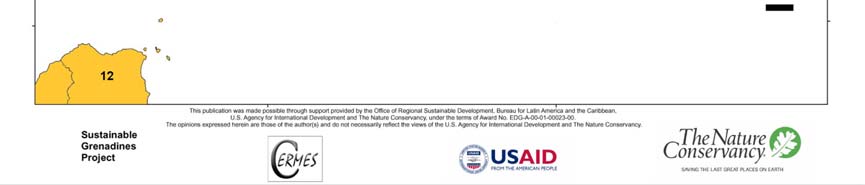

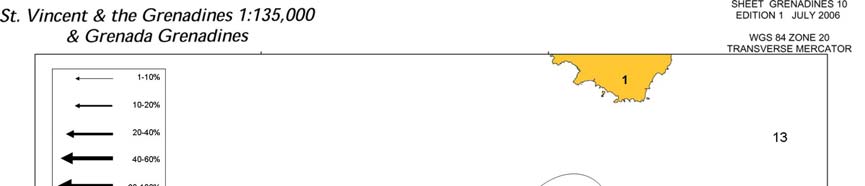

Figure 3.1 Map of the Grenadine Islands showing the study site

The Grenadines are older and more geologically complex than the St. Vincent mainland and

the shallow bank hosts a multitude of reef systems, mangroves and seagrass beds which

provide habitat for a wide diversity of plant and animal species. Three quarters of the

Grenada Bank is less than 50 m deep allowing for extensive bottom habitat for coral reef

formation (CCA/IRF 1991) and a productive fishing area. Shallow reefs host species such as

echinoderms, hard and soft corals, crustaceans, sponges and a wide variety of reef fish (Price

& Govindarajulu 1998, Comley et al. 2002). All of these combine with the wide open spaces

to create a spectacular picturesque land and seascape that attracts visitors from all around the

world.

The many islets and bays in the Grenadines allow for mangrove ecosystems and sea grass

beds. These act as nurseries for many commercially important species. In Tyrell Bay,

7

Carriacou, the Oyster Bed mangrove hosts thousands of oysters which filter feed on the roots

on the red mangrove trees and act as a natural harbour to boats during storms. Seagrass beds

in islands such as the Tobago Cays and Union Island support a wide diversity of species

including rays, turtles, starfish, squid and juvenile fish.

The Grenadines experience very low rainfall (sometimes as low as 460mm) compared to

1700mm on the St. Vincent mainland (Culzac-Wilson 2003). This impacts on the availability

of water to the local population that relies in part on storing rain water. This has also led to a

greater dependency on the sea for food and income than on the land (Jardine & Straker 2003).

3.1.1 Natural threats: Hurricanes

The Grenadines are located below 13o north, placing them just below the main hurricane belt.

However in the last half century, occasional hurricanes such as Hurricane Janet, Allen, Ivan,

and Emily have caused severe damage to infrastructure and the natural environment. These

hurricanes also severely impacted the boating, fishing and yachting industry on which the

Grenadines rely heavily (Cooke et al. 2005). In 1982, Hurricane Allen devastated the fishery

sector in the Vincentian Grenadines (Mohammed & Rennie 2003). The recent 2004

Hurricane Ivan affected mainland Grenada and its Grenadines to the point that restoration

efforts have not yet been completed. After the hurricane, news reports out of Grenada stated

that 90% of the houses in Grenada were damaged. Some of the reefs in the southern

Grenadines (e.g. leeward side of Sandy Island, Carriacou) suffered extensive damage which

may take decades to recover. Fishers (especially those in the Southern Grenadines) stated that

Hurricane Ivan has drastically reduced their catch (mainly lobsters and demersals) and have

severely altered the bottom habitat.

3.1.2 Society and economy

The population density on most of the Grenadine islands is relatively low and communities

are spread apart in towns and/or rural villages. Many of these rural villages are hubs for

fishing activities. Around 1991, reports stated that the majority of the male population in the

Vincentian Grenadines were fishers or actively involved in a related sector and it is the main

income earner for many households (CCA/IRF 1991). This creates vulnerability among a

large section of the population as they depend heavily on one industry. Some of the fishers

combat this by diversifying their income through other occupations such as: water-taxiing,

construction, transportation of goods between islands and small-scale agriculture (Cooke et

al. 2005).

The Vincentian and Grenada economies have been historically driven by agriculture. In the

Grenadines, marine resources play a vital role in food security, sustaining livelihoods and in

the cultural and social activities. As the land in the Grenadines is not very productive for

agriculture (Jardine & Straker 2003), many made their living from fishing as it was one of the

few options for employment, especially after the second World War (Mohammed et al.

2003). For example, in the 1960s, the conch fishery became the most significant economic

activity on Union Island.

Tourism has been the driving force for the economy of many Caribbean islands and has been

increasingly becoming part of the Grenadine economy (Statistical Office 2001). In 1985, St.

Vincent & the Grenadines saw a change where the majority of tourist arrivals shifted from

the mainland to the Grenadines (CCA/IRF 1991). Due to the attraction of the Tobago Cays,

many flock from around the world to this anchorage. It is estimated that 84% of yachters

visiting the Vincentian Grenadines make a stopover in the Tobago Cays (ECLAC 2004).

Tourism has significantly impacted the people of the Grenadines. In the 1990s, the tourism

boom from resorts on Petite St. Vincent and Palm Island attracted many away from fishing in

8

the southern Grenadines into job opportunities such as construction (Chakallal et al. 1994). It

has brought foreign exchange, employment and additional revenue from tourist taxes and

expenditure (ECLAC 2004). However, tourism has also brought loss of amenities and

negative environmental impacts such as reef and sea grass damage from anchors and sewage.

Verbal reports of tourists spearfishing illegally within the Tobago Cays were common and

this poses a significant threat to the effectiveness of the marine protected area (MPA). Not

many of the fishers are involved in or work within the tourism sector. The main interaction

between fishers and the tourism sector in the Grenadines is the sale of catch, especially

lobster. Here fishers receive a much better price in restaurants, hotels and to tourists directly.

With an expected increase in tourism arrivals, the market for fish is expected to increase

consequently over the years.

3.1.3 Marine Protected and Conservation Areas

Within the Grenadines there are nine marine conservation areas (Kirby-Straker 2003) all of

which are in the Vincentian Grenadines. The Sandy Island/Oyster Bed Mangrove area is a

proposed marine park in the Grenada Grenadines which is currently operating informally.

Out of the nine marine conservation areas, the Tobago Cays marine park is the only marine

protected area in the Grenadines where fishing is completely prohibited within the

boundaries. However one of the traditional fishing camps is located within its MPA on Petit

Tabac and it appears that the fishers were not consulted when the park was being established.

Fishers frequent this area to access the rich fishing areas within the Tobago Cays and it is a

known turtle fishing site. Some of the fishers seem resentful towards the establishment of this

park and there is also concern over the rumoured establishment of another park in the east

coast of Canouan. It is unclear whether or not fishers still utilise the camp in the Tobago

Cays. Many believe that enforcement is lacking and that fishing occurs regularly within the

park by locals and visitors.

3.2 Island profiles

3.2.1 Bequia

At 8.1 km2 (SusGren 2005) Bequia is the most northerly and largest of the Vincentian

Grenadine islands (see Figure 3.1). As with all of the Grenadine islands, Bequia was

originally inhabited by the Arawaks and then later Caribs before the first European settlement

in the early 18th century (Bequia Tourism Association 2006). After the Vincentian

Grenadines were handed over to the British, many rich and poor settlers came and set up

plantations on the island. By 1828, sugar production peaked and soon crashed afterwards and

thus many of the wealthy settlers left the island (Bequia Tourism Association 2006).

Boat building and sea faring are a rich part of Bequia's heritage. As the islands are totally

dependent on trade, maritime activities were not new to Bequians (Bequia Tourism

Association 2006). Admiralty Bay was the main port on this island, with imports of many

supplies and exports of sugar, lime, molasses and cotton. The island's boat building industry

was supported by the abundance of white cedar trees which are excellent for boat

construction which is still used to this day (Belmar 2006). Many of the island's first settlers

were seamen and carpenters and by the 1900s, Bequia led the Grenadines in boat and ship

building and whaling (Bequia Tourism Association 2006).

Bequia hosts an annual fishing competition on Fisherman's Day where many of the artisanal

fishers from around the Grenadines compete for prizes. This event which is organised by the

Rotary Club, promotes the importance of the fishing industry within the Grenadines and it is

attended by locals and visitors alike. In July 2006, 46 fishers (19 boats) from around the

9

islands participated in a competition. At this competition around 530.7 kg of fish were caught

and immediately sold due to the large demand of fish. This was a complete opposite to what

is usually seen on normal fishing days were the fishers were complaining of lack of demand

and market to sell their catch. This event can be repeated elsewhere promote the fishing

industry in other fishing communities.

3.2.2 Canouan

"Cannoun", which is Carib for turtle is located in the middle of the Grenadine archipelago

(Miller Publishing Company. 2004a). At 7.8 km2 (SusGren 2005), a large portion of

Canouan is owned and managed by foreign owners. Eight hundred of the 1830 acres is owned

by Italian investors (Canouan Resource Development Limited) and utilised in the tourism

sector (Miller Publishing Company 2004a).

Recently there were announcements of proposals for a marine conservation area on the

Atlantic side of the island. Some see this more as an attempt to place more restrictions on the

movement of locals on the island which will have a negative impact on the livelihoods of

fishers, than a genuine conservation initiative.

3.2.3 Carriacou

Carriacou is the largest of the Grenadine islands (33.7 km2 (SusGren 2005)). The name

Carriacou is Carib for "land of the reefs" (Price & Govindarajulu 1998) and this island has a

assortment of sea grass beds, reefs and mangroves, each hosting a great diversity of plant and

animal species. One of the island's major mangrove systems, Tyrell Bay, is an important bay

for seine fishers. The Tyrell Bay marina currently under construction may have a great

impact on mangroves and reefs in the area thus affecting the fishery. Many of the fishers

recognise this area as an important nursery area for many commercially important species

such as robins, jacks, snapper and barracuda. There is also concern over the Environmental

Impact Assessment (EIA) process of this project and locals believe that their views were not

taken into consideration and that this project would subsequently negatively impact their

livelihoods.

On this island, there appeared to be more job diversity than on the other smaller islands (e.g.

agriculture, larger construction and services sector, trade, etc.). The major settlements on

Carriacou coincide with the major fishing villages. Here many of the Scottish and Irish were

concentrated and it is now made up of mostly fishers. The houses in this area seem to be in

very good condition indicating a reasonably high standard of living. In Hillsborough there is

a resident fisheries officer with the mandate of supervising fisheries in Carriacou and Petite

Martinique. The fish market in Hillsborough appeared to be very active at the time of the

survey with fishers selling their catch relatively easy. Although the island is large, there is

only one major gas station on the island and fishers have to travel into Hillsborough to

purchase fuel. The government is planning to build a fisheries complex in Hillsborough that

will be able to process the landings of the fishers with a focus of meeting the international

Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) standards.

3.2.4 Mayreau

Mayreau is the smallest of all the Grenadine islands (2.6 km2 (SusGren 2005)). The island

consists of one main village with a small close-kit community of around 170 persons. In the

north, Saltwhistle Bay is a calm leeward bay which is a major stop for yachters travelling to

the Tobago Cays. On the island there is one major hotel and a few guest houses and

restaurants. Fishers here have few options to sell on the island so many rely on trading

10

vessels. Hurricane Ivan caused a bit of damages to homes and one fisher was encountered

who after 2 years is still rebuilding his home.

3.2.5 Mustique

Mustique, the only inhabited private island in the Northern Grenadines, is 5.2 km2 (SusGren

2005). In 1968, the Mustique Company was formed and was developed with the goal of

enhancing tourism on the island (Miller Publishing Company 2004b). Persons who purchase

property on the island buy shares and become part of the company. Locals however live in

specific designated areas in gated communities and access to the island is regulated. Workers

who do not live on the island use ferries to come from St. Vincent.

3.2.6 Petite Martinique

Petite Martinique is a small volcanic dome located 4.5 km to the east of Carriacou (Price &

Govindarajulu 1998). The island has a population of about 800 and is supported by

unregulated marine trade, fishing and boat building (Price & Govindarajulu 1998). Many

Scottish and Irish shipwrights and sailors arrived in Petite Martinique after emancipation and

helped to establish the fishing industry on the island (Logan 2001). Even now, fishing is the

main economic activity on Petite Martinique (Logan 2001). One fisher on the island stated

that there are no real resources for agriculture or infrastructure for tourism and thus fishing is

the only major option for persons entering the workforce. The island which is only 2.3 km2

(SusGren 2005) contributes 15% of Grenada's fish landings (Food and Agriculture

Organization 2000) and the majority of trading vessels in the Grenadines are based off this

island. Fishers are able to sell directly to the trading vessels most of which export to

Martinique. The island has an ice machine which is heavily used by the longline fishers and

is much cheaper than ice sold in the some of the other islands. As with Winward, Carriacou,

the homes on the island indicate a relatively good standard of living amongst fishers. Many

fishers leave island for extended periods of time to engage in the longline fishery based in

Grenada which exports to the Unites States.

Petite Martinique is the only island with an active fishing cooperative. Here gear and

concessions are sold and the facilities are expanding with locker facilities and a boat docking

site. As the co-op was operating at a loss under the government's control, the cooperative was

leased to the current president of the co-op. Although many fishers in the Grenadines see

cooperatives as beneficial, participation in the Petit Martinique co-op is low (i.e. only 15

members on an island with an estimated 150-200 fishers). Even with a very low fee of EC $5

per month, fishers are not paying their monthly dues. Due to a lack of funds, the cooperative

store is leased to the current president who also stated that the co-op has a considerable

amount of debt.

3.2.7 Union Island

Union Island is one of the largest of the Vincentian Grenadine islands (8.3km2 (SusGren

2005)) and is located on the southwest edge of the Grenada bank (Price & Price 1998).

Fishing was the major economic driver around the mid twentieth century (Mohammed et al.

2003) and presently Tourism is becoming a significant contributor to the economy of Union

Island. Flights bring tourists to transfer to the nearby private Palm Island and Petite St.

Vincent.

The island, similar to Carriacou has a network of sea grass beds, mangroves and coral reefs.

The two main fishing villages in Union Island are in Ashton and Clifton. These are also the

sites for two large lagoon ecosystems (Price & Price 1998). Clifton is the tourism centre of

the island with most the major hotels, restaurants, airport and other amenities. Many yachts

11

frequent Clifton Harbour and the island has the highest population of watertaxi operators

(Cooke et al. 2005).

Ashton is a more community based, rural fishing town that is located in the south of the

island. Union Island has had a history of unsustainable large scale developments and

environmentally unfriendly planning. In Clifton, the development of the airport resulted in

the levelling of Red Island (a protected area), destruction of a mangrove, and the reduction in

current flow within the lagoon, causing an increase in pollution retention time (Price & Price

1998). In Ashton, the lagoon hosts a multiplicity of ecosystems: coral reefs, seagrass beds,

salt marshes, mangroves, etc. Frigate Island which lie on the boundary of the lagoon was

designated a marine conservation area by the 1986 Fisheries Act (Price & Price 1998).

However, in spite of all of this, the 300 bertha marina was scheduled to be built along with a

50 acre golf course and a large condominium complex (Price & Price 1998). This

immediately reduced the current flow in the lagoon and thus a reduction in water quality by

increased suspended sediment, increased chlorophyll concentration due to nutrient build-up,

and consequently reduced coral reef and seagrass health and live cover (Goreau & Sammons

2003). Fishers have stated that this has negatively impacted on fish populations in the area

and subsequently reduced their catch rates.

3.3 Fisheries Infrastructure

3.3.1 Canouan Fisheries Complex

The Canouan fisheries complex was constructed by the Japanese government. Similar to the

complex in Mustique, this complex consists of sleeping quarters, storage and locker facilities,

refrigerators for cold storage and other infrastructure such as compressor (scuba tank refills)

and desalination equipment. Almost all the fishers that utilise this complex are from Paget

Farm, Bequia and pay approximately EC $35 per week in rent. A large portion of the fish is

sold to the government and stored at the facilities. This fish is then sold primarily to

restaurants and hotels on the island. Locals purchase fish at a small stall in Charlestown and

not many locals were observed going the fishing complex. Competition among fishers was

stated to be one of the main reasons why they choose to leave Bequia.

3.3.2 Clifton Fisheries Complex, Union Island

In 1994, the Japanese built a fishery complex in Clifton similar to the facility in Bequia.

Many suspect that the Japanese government is using these contributions as an incentive for

voting to lift the ban on whaling (see information on whaling in Section 3.4.2). Although this

facility would be more than adequate to cope with landings, the operational costs were too

high for the government and thus the facility is not utilised. As a result, fishers in Union

Island complain of not having enough amenities available to them. As the complex is not in

use, there are no real storage facilities available, especially for fishers with large catches. The

intention of the facility was to have storage racks where fishers can keep catch and lockers

for gear. Water scarcity is also a problem in Union Island. This impacts on the cost and

availability of ice to the fishermen, especially since the ice machine in the fishing complex is

not in operation. One fisher reported that the cost of ice in Union Island is times the amount

sold in St. Vincent. The island also lacks a gas station and fishers purchase gas from the

Anchorage Yacht Club and a local market retailer usually at a higher than normal price. A

representative of the government stated that once St. Vincent & the Grenadines receive the

license again to sell to the European Union, they will re-open the complex. Offers to lease it

to a private operator failed due to the high overhead costs of the facility.

12

3.3.3 Paget Farm Fishing Complex, Bequia

Paget Farm is the most active fishing village in Bequia. In 1994 the Japanese built a large

fishing complex in Paget Farm with facilities for storage and cleaning, ice machine, offices

and a research lab. There is also a built-in desalination plant which is necessary to operate

such a large facility in a water scarce island. Despite all of this, the complex was not utilised

due to high operational cost. The facilities have only been recently opened and leased to a

local company called Grenadine Seafood Distributors. The company estimates the monthly

overhead costs for the facilities at EC $7,000 for utilities and EC $7,000 for rent. The

company is currently investigating the use of solar technology for electricity to reduce some

of these costs. There are also plans to use the desalination plant to help supply some of the

Paget Farm community with potable water. The company was expecting around $1,000-

$2,000 in fish per day (primarily demersals) which will be aimed at the export market.

3.3.4 Lobster Storage Facilities, Bequia

Due to concern over the European Union ban on the importation of fish from St. Vincent &

the Grenadines, a live lobster pool was built next to the docks in Paget Farm. This was to

keep the lobsters alive as long as possible, reducing the chance of tissue decay. It is

approximately 450 cubic feet and is maintained and operated by a local fisher. A major

Barbadian importer purchases lobster from the fisher which are subsequently transported and

sold in Barbados at restaurants and hotels. The Grenadine Seafood Distributors were also

developing plans to create their own live lobster pools for facilitating export.

3.3.5 Mustique Fishing Complex, Mustique

The Mustique Company owns and operates the fishing complex on the western side of the

island. Fishers here have living quarters, cold storage, cleaning area, cooking area a haul up

site. Rent at the facility is free; however, the fishers have to pay for utilities. Most of the

fishers here are older Bequian fishers from Paget Farm. The company buys from fishers and

sells to tourists, private houses. Some tourists come to buy fish for consumption and to use as

bait for game fishing (e.g. robins, jacks).

3.4 History and development of fishing

3.4.1 Grenada and its Grenadines

Prior to the 1950s, the main fisheries in Grenada and its Grenadines were the flying fish and

offshore pelagic fishery, beach seining and handlining for demersals (Mohammed & Rennie

2003). There was also a significant amount game fishing associated with tourism. It was in

the 1940s that researchers started to notice the decline in demersals fish stocks in the

Leeward Islands and began to encourage a shift towards offshore pelagics and deep slope

species (Mohammed & Rennie 2003). After World War II, there was an influx of inboard

gasoline engines at lower costs and these were used on double enders, whalers and pirogues.

During this time as well, there were price controls instated on fish to ensure affordability,

even when landings were low (Mohammed & Rennie 2003).

Demersals remained the most important species group in the second half of the last century

and the influence of fish pots and the mechanisation of the pelagic fleets on the mainland

began to spread to the smaller islands. Sloops from the mainland were used with handline and

troll lines to fish for demersals in the Grenada and Vincentian Grenadines. Up to the 1970s,

traditional fishing gear and small scale fisheries still dominated Grenada its Grenadines. Row

boats were used to fish for demersals near to shore and it is expected that this was also

practiced in the Grenadine islands as well. There was also a trend towards younger boat

13

owners buying motorised boats and older fishers using the traditional row boats and double

enders.

The Artisanal Fisheries Development Project was established in 1982 as an effort by the

government to expand the fisheries sector. The goal of this US$2.7 million project was also

to increase employment, reduce fish imports, expansion of fish markets, duty-free prices on

fishing equipment and a marketing mechanism for sale of produce (Mohammed & Rennie

2003). With the donations of vessels from Cuba and other linkages, longlining skills and gear

were transferred to Grenadians. There was also a significant change of the use of flying fish

from human consumption to becoming primarily a bait fish. By the 1990s, the processing and

export market was well established with yellowfin tuna, swordfish and sailfish being some of

the major export species. With the increase in infrastructure and market for offshore pelagics,

the decline in the demersal fishery and government incentives that fishers in the Grenadines

began to switch to longlining (Mohammed & Rennie 2003). Even today, many of the Petite

Martinique fishers spend most of their time on longlining vessels based in Grenada.

3.4.2 St. Vincent and its Grenadines

There is the clear distinction between fisheries of the St. Vincent mainland and those of the

Grenadines. The Vincentian fisheries focus on inshore and offshore pelagics, with the

occasional humpback whaling whereas Grenadine fisheries target mainly inshore and deep

slope demersals, lobsters, conch and whales (Mohammed et al. 2003).

Due to the size of the fishery and its unreliability, the market for fish and shellfish did not

develop till after the 1940s. In addition, as the industry was not developed and most fished at

the subsistence level, the majority of the population got their source of protein from salted

cod imported from Newfoundland (Mohammed et al. 2003). Trade was limited by the

availability transport and distance, only a few islands like Canouan exported to the

"mainland" (i.e. the island of St. Vincent) and some exported turtle shell to Trinidad.

Nearing the middle of the last century, Canouan began to "process" fish by salting demersals.

In the 1940s (similar to Grenada), a price control was placed on fish.

After World War II, there was an influx of persons entering the fishing industry due to a lack

of other opportunities (Mohammed et al. 2003). The trade relationship between Martinique

and the Grenadines began around the 1950s. In the period of 1955-1958 about 227 t of fish

were traded and this new market led to an increased interest in the industry. Increasing

regional demand for species such as conch in Trinidad and Grenada led to the development of

the conch fishery in Union Island in the 1960s. By the 1970s as catch and effort increased,

all of the conch exports were diverted to Martinique and signs of overexploitation became

evident. As time progressed, Bequia became the major exporter of demersals and lobster to

Martinique. Canouan exported iced and salted fish to St. Vincent and Grenada and iced fish

less frequently to Dominica and St. Lucia.

In the 1960s there was an effort by the government, the Food and Agriculture Organization

(FAO) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) to advance the industry.

Efforts were made to offer duty-free concessions on gear, timber and engines were made but

were not successful. Another program was initiated to guarantee prices to French Antilles'

companies for the sale of fish but this also was not successful.

In the 1980s, a combination of Hurricane Allen, rising fuel prices, high cost of engines and

scarcity of spare parts caused a severe decline in the Grenadine fishery. Indications of

overexploitation of many species also became evident in the 1980s. Low abundance in

shallows and smaller sized lobsters increased fishing effort (scuba and faster boats) and

deeper fishing for demersals all testified that species were being overfished especially in the

14

shallower waters. It was recognised by managers that demersals on deeper banks and offshore

pelagics could withstand increased effort (Mohammed & Rennie 2003).

Whaling began as the most important fishery in the Grenadines (Mohammed et al. 2003).

There was a significant number of whalers from the Eastern United States that settled in the

Grenadines. In the 1870s, William Wallace Jr. started the first whaling station in Friendship

Bay (Bequia Tourism Association 2006). Another whaling station was subsequently set up by

Joseph Ollivierre on Petit Nevis (Whale and Dolphin Conservation n.d). The landing of a

whale is a significant community event and the majority of the whale meat is distributed

amongst the locals and little of the whale by-products are wasted. Whale oil became the

fourth most valuable export of the country (Bequia Tourism Association 2006). Between the

1890s-1925, it was estimated that 25,000 to 500000 imperial gallons of whale oil produced

from the six St. Vincent and Grenadine stations (Whale and Dolphin Conservation n.d).

Bones and some of the other by products (e.g. baleen) are used in furniture and in home and

building décor. Even to this day, whaling in the Grenadines is still conducted using the same

techniques that were used when the fishery first began there. Fishers travel out to sea in a

small double-ender (previously a dug out canoe) with a small crew and would use harpoons

to strike and capture the whales. The majority of whales targeted are humpbacks which

migrate south during the Northern Hemisphere winter (see Appendix 3).

In 1987, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) recognised the aboriginal, subsistence

use of humpback whales by Bequians (Whale and Dolphin Conservation n.d). Schedule

paragraph 13(4) of the International Whaling Commission regulations allows for the "taking

of [ ] humpbacks by Bequians of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, but only when the meat and

products of such whales are to be used exclusively for local consumption in the St. Vincent

and the Grenadines" (Whale and Dolphin Conservation n.d). Currently there is a quota of 3

whales and the harvesting of sucking calves and females with sucking calves is forbidden.

However, it was noted that calves were landed in 1992, 1993, 1998 and 1999 and escorts

were killed as they attacked the boat attempting to defend the other whale (Whale and

Dolphin Conservation n.d).

3.5 Current status of fishing in the Grenadines

3.5.1 Data limitations

As the Grenadines are many small, dispersed islands with very little government

administrative infrastructure, obtaining current and accurate data on landings is very

challenging. It is not unexpected to see that most of the fisheries statistics and information are

for the mainland and very little is documented separately for the Grenadines. It was also

noted that the catches for inshore and reef species were vastly underrepresented in Grenada

fisheries statistics as some of the important landing sites are not recorded (Mohammed and

Rennie 2003). Similar data gaps exist in the Vincentian Grenadines as well (Chakallal et al.

1994)

3.5.2 Economic value

According to a recent FAO report, it is estimated that 1,120 tons is landed in St. Vincent and

the Grenadines each year (Food and Agriculture Organisation 2002a). In 2000, exports from

fishing in St. Vincent & the Grenadines was valued at US $961 000 (Food and Agriculture

Organisation 2000a). In Grenada and the Grenada Grenadines, the export of tuna to the U.S.

market contributes US $3.5 million of foreign exchange to the economy (Food and

Agriculture Organisation 2000a). Fishing contributes 2% to the Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) in St. Vincent & the Grenadines and 1.5-2% in Grenada (Food and Agriculture

Organisation 2000a, 2002a). This however does not reflect the value of fisheries to the people

15

of the Grenadines as the total GDP include industry and agriculture on the St. Vincent and

Grenada mainland where the majority of the population lies. The proportion of each species

group landed in St. Vincent and the Grenadines are as shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Composition of average annual total landings in St. Vincent & the Grenadines by species group

Species Group

Percentage (%) of Total Annual

Landings

Shellf

ish 5

Demersals 10

Small Coastal (inshore) pelagics

45

Offshore pelagics

35

Other species

5

(Source: Jardine & Straker 2003)

The market for fish in the Grenadines is small and the majority of the fisheries are small-scale

using small fiberglassed boats and/or wooden crafts with one or two gasoline powered

outboard engines (Chakallal et al. 1994). Through observation it is evident that this is still

characteristic of the fishery. Overall demersals species are the most important with

handlining being the preferred fishing technique (Mohammed & Rennie 2003). In 2005,

demersals constituted 94% of the total landings in Carriacou (Statistical Division 2006).

There is no fisherfolk organisation for the fishers in the Vincentian Grenadines, Petite

Martinique in the Grenada Grenadines being the only island with a fishing cooperative.

3.5.3 Trading vessels

Fish trading vessels visit bays around the Grenadines and fishers sell their catch directly to

their boats (Jardine & Straker. 2003). In the period of 1996-2000, 118.6 tons or 13.1% of the

average annual landings in St Vincent & the Grenadines went directly to trading vessels. In

Petite Martinique, 98% of all the fish caught are exported to Martinique (Logan 2001) mostly

by trading vessels. This is supported by previous studies which reported that the majority of

the finfish from the Grenada Grenadines were exported to Martinique (Chakallal et al. 1994).

Currently, there are a total of 7 trading vessels operating in the Grenadines, most of which

operate out of Petite Martinique and Carriacou. The trading vessels are usually sloops with a

mast and are around 12-20 metres in length and driven by a >120hp engine (Chakallal et al.

1994). These vessels usually spend most of their time in Grenadines and 3-5 days to travel

and unload their stock. Martinique is one of the major buyers of fish from the Grenada

Grenadines with estimates of receiving 85% of all finfish exported to this island in 1990

(Chakallal et al. 1994). At around that time as well, 539.8 mt or 70% of total (Vincentian and

Grenada Grenadines) landed catch were exported to Martinique (Chakallal et al. 1994).

During the study, it was observed that the trading vessels accept mainly demersal species as

well as offshore pelagics. On some of the trading vessels, it was observed that species such as

Doctorfish and Ocean Surgeon (Acanthuridae sp.) were not accepted, neither was any fish

less than 9 inches in fork length (to ensure compliance to the European Union standards).

However, the fork length of each fish was estimated rather than measured.

3.5.4 European Union ban and quality control

In 1999, the European Union began to put restrictions in place on the imported fish into its

territories (Logan 2001). These included setting up standards of handling and procession that

had to be met and to promote better fishing practices (e.g. rejection of juvenile fish). This

resulted in a ban the importation of fish from St. Vincent & the Grenadines. Since then, the

16

Vincentian government has begun to improve the conditions within the fish markets to meet

the international standards. This includes encouraging the use of ice on vessels and in

vending stalls, acquisition of devices for monitoring bacteria, heavy metals, etc from the

Japanese and European Union and the training of fisheries staff in quality control and

assurance (Food and Agriculture Organisation 2002a). It is not clear when the next round of

inspections will take place so as to assess the new operating and processing conditions.

According to the Fisheries Division Officer for the Grenada Grenadines, the government has

successfully implemented quality control and assurance practices within the fishing industry.

With the threat of losing access to this vital market, the government was motivated to put the

necessary measures in place to meet the new standards. This was a coordinated effort with the

local government, fishers and the private vessels where the Grenada government provided

free training for the private trading vessel staff and fishers to reach the widely recognised

HACCP standards.

3.6 Fisheries management