CERMES

Technical Report No 8

Determination of the Socio-economic Importance of

the Lobster Fishery of the British Virgin Islands

GREGOR

Y FRANKLIN

Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES)

University of the West Indies, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences,

Cave Hill Campus, Barbados

2007

ABSTRACT

Determination of the socio-economic importance of the

lobster fishery of the British Virgin Islands

GREGORY FRANKLIN

The British Virgin Islands is heavily dependent on tourism and the Caribbean spiny lobster

(Panulirus argus) is one of the delicacies which the visitors enjoy. The British Virgin Islands

1998 Fisheries Management Plan identified signs of overfishing in the lobster fishery throughout

the territory with acute overfishing in certain areas. Measures were implemented in the 2003

Fisheries Management Regulations aimed at conserving this species. Among these measures, the

closed season for lobster, from March through June, was the one expected by the stakeholders to

cause hardship. This closed season was expected to have negative socio-economic impacts on

fishers and restaurants. These stakeholders therefore asked for a socio-economic survey to be

made. This survey was arranged by the Conservation and Fisheries Department of the Ministry

of Labour and Natural Resources which has responsibility for the fishing industry.

The objectives of the survey were to determine the economics of the lobster fishery in respect of

expenditure and revenue and describe its social importance to the stakeholders. It was also to

update and expand a previous economic survey to specifically include lobster. The survey was

also to establish or strengthen linkages among stakeholders for research on the lobster fishery

through the use of participatory research methods and to recommend a system of socio-economic

monitoring for the lobster fishery. The primary methods for conducting the survey were

questionnaires, focus group meetings and key informant interviews.

Results show that most of the lobster fishers have made a significant investment in the fishery

and are highly dependent on it for personal income. There is interdependency between fishers

and restaurants, and a few family enterprises exist where boat and restaurant are owned by same

person. The newly imposed closed season for lobster can cause a loss of income to the

stakeholders because of its timing which starts at the peak in tourist arrivals to the territory and

continues almost to the end of the tourist season. Some recommendations are made for

strengthening the participation of stakeholders in further research on the lobster fisher and for

establishing a system for regular socio-economic monitoring.

Keywords: British Virgin Islands, Socio-economic survey, Caribbean spiny lobster

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am especially grateful to those who made this project possible and the many people who

assisted and encouraged me in completing it. I thank the Government of the British Virgin

Islands, in particular, the Conservation and Fisheries Department of the Ministry of Labour and

Natural Resources, for hosting me and facilitating the research.

Conducting the survey was critical to this project and this task could not have been accomplished

without the help of Ms. Abbi Christopher, Mr Samuel Davies, Mr Arlington Pickering, Mr Ken

Pemberton, Mrs. Jasmine Hodge-Bannis; to them my thanks are extended. I also wish to express

gratitude to the presidents of the Virgin Gorda Fishermen's Cooperative and of the Jost Van

Dyke Fisherfolk Association and the participants in the survey.

Much appreciation is expressed to my supervisor, Dr Patrick McConney, Snr. Lecturer

CERMES, and my external supervisor, Mrs Christine Chan-A-Shing, the Fisheries Officer

(BVI), for their invaluable advice and assistance with this task.

Special thanks to my CERMES colleagues: Danny for his assistance with aspects of the project

during our sojourn in The BVI; and to Bertha, Katherine, and Amanda.

ii

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT...........................................................................................................................I

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................................II

1

INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................................1

1.1

GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION..............................................................................................................................1

1.2

FISHING AREA .............................................................................................................................................2

1.3

FISHERIES IN THE BVI .................................................................................................................................2

1.4

SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT OF LOBSTER FISHERIES MANAGEMENT...............................................................3

1.5

HOST ORGANISATION ..................................................................................................................................3

1.6

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ...............................................................................................................................3

1.7

ORGANISATION OF REPORT..........................................................................................................................4

2

METHODOLOGY.............................................................................................................................................4

2.1

SOCIO-ECONOMIC SURVEYS ........................................................................................................................4

2.1.1

Fishers questionnaire ............................................................................................................................4

2.1.2

Restaurant questionnaire.......................................................................................................................5

2.1.3

Key informants.......................................................................................................................................5

2.1.4

Focus groups .........................................................................................................................................5

2.2

DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION.......................................................................................................6

2.3

LIMITATIONS ...............................................................................................................................................6

2.4

SECONDARY DATA ......................................................................................................................................6

3

RESULTS ...........................................................................................................................................................7

3.1

LOBSTER FISHERY OVERVIEW......................................................................................................................7

3.2

FISHERS SURVEY .........................................................................................................................................9

3.2.1

Demographics........................................................................................................................................9

3.2.2

Livelihoods...........................................................................................................................................11

3.2.3

Vessels .................................................................................................................................................13

3.2.4

Ownership, kinship and sharing ..........................................................................................................14

3.2.5

Local knowledge of lobster biology .....................................................................................................16

3.2.6

Catch and effort ...................................................................................................................................17

3.2.7

Revenue................................................................................................................................................21

3.2.8

Maintenance and operating costs ........................................................................................................22

3.2.9

Marketing arrangements......................................................................................................................25

3.2.10

Attitudes and perceptions regarding the resource and management ..............................................25

3.2.11

Lobster closed seasons and other regulations ................................................................................26

3.3

RESTAURANT SURVEY...............................................................................................................................28

3.3.1

Closed restaurants ...............................................................................................................................28

3.3.2

Patrons.................................................................................................................................................29

3.3.3

Tourist arrivals ....................................................................................................................................30

3.3.4

Restaurant size.....................................................................................................................................31

3.4

FIRST FOCUS GROUP MEETING ...................................................................................................................31

3.4.1

General recommendations for the lobster fishery................................................................................31

3.4.2

Entry into fishing and alternative income............................................................................................31

3.4.3

Threats to the lobster fishery ...............................................................................................................32

3.4.4

Opinions on fisheries regulations ........................................................................................................32

3.4.5

Relationship with the fisheries authority .............................................................................................32

3.4.6

Where fish is sold.................................................................................................................................33

3.5

SECOND FOCUS GROUP MEETING ...............................................................................................................33

3.5.1

Number of fishers.................................................................................................................................33

3.5.2

Where fish is sold.................................................................................................................................33

3.5.3

Gear, threats and abundance...............................................................................................................33

3.5.4

Registration and relationship with the fisheries authority...................................................................34

3.5.5

Opinions on fisheries management......................................................................................................34

4

DISCUSSION ...................................................................................................................................................35

4.1

SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF THE LOBSTER FISHERY .......................................................................35

4.1.1

Fishers .................................................................................................................................................35

iii

4.1.2

Restaurants ..........................................................................................................................................37

4.1.3

Others ..................................................................................................................................................38

4.2

LINKAGES AMONG STAKEHOLDERS FOR PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH.........................................................39

4.3

SOCIO-ECONOMIC MONITORING FOR THE LOBSTER FISHERY......................................................................40

5

REFERENCES.................................................................................................................................................42

6

APPENDICES ..................................................................................................................................................44

APPENDIX 1: FISHER'S QUESTIONNAIRES .................................................................................................................44

APPENDIX 2: ATTITUDES AND PERCEPTIONS REGARDING RESOURCES AND MANAGEMENT....................................51

APPENDIX 3: RESTAURANT QUESTIONNAIRE ...........................................................................................................54

APPENDIX 4: FIRST FOCUS GROUP MEETING ............................................................................................................56

APPENDIX 5: SECOND FOCUS GROUP MEETING ........................................................................................................57

APPENDIX 6: COST OF SAFETY EQUIPMENT..............................................................................................................58

APPENDIX 7: QUESTIONNAIRE ON BACKGROUND INFORMATION FROM FISHING COMPLEX .....................................59

Citation: Franklin, G. 2007. Determination of the socio-economic importance of the lobster

fishery of the British Virgin Islands. CERMES Technical Report No. 7. 59pp.

iv

1 INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this paper is to determine the socio-economic importance of the lobster fishery of

the British Virgin Islands. This socio-economic study was executed as a research project during

an internship hosted by the Conservation and Fisheries Department (CFD) of the Ministry of

Natural Resources and Labour of the Government of the British Virgin Islands.

The department seeks to manage the natural resources of the British Virgin Islands in a

sustainable manner. It was formed specifically to address the growing environmental stresses

that the British Virgin Islands are experiencing.

This socio-economic survey aims to provide knowledge about the importance of the lobster

fishery to individuals and groups of stakeholders. It will assist the CFD in gauging the impacts of

new fisheries regulations on these stakeholders and in implementing adequate management for

the fishery, especially by involving stakeholders in decision-making to help determine whether

the lobster closed season will have negative socio-economic impacts.

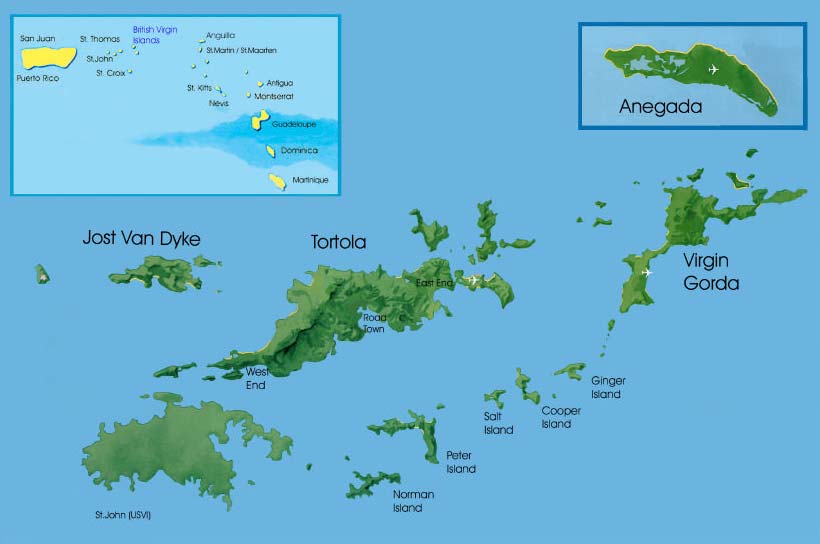

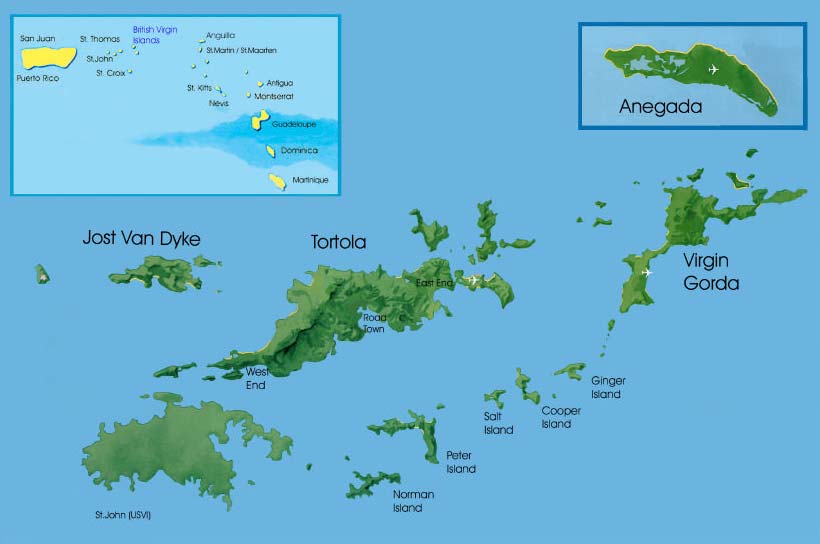

1.1 Geographic location

The British Virgin Islands (BVI) is an archipelago comprising thirty six islands, islets and cays

situated in the Eastern Caribbean at longitude 64°30'W and latitude 18° 30'N (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Map of British Virgin Islands

Sixteen of these islands are inhabited. The main islands include Tortola which is linked by a

bridge to nearby Beef Island, Anegada, Virgin Gorda and Jost Van Dyke. The islands together

constitute a total area of 153 km2 (59 square miles) with a territorial sea of 1,489 km2 (575

square miles) The British Virgin Islands are located on the same geological shelf as Puerto Rico

and the US Virgin Islands, with the exception of St. Croix. (The Development Planning Unit,

Government of BVI, 2005).

1

1.2 Fishing area

The total shelf area is approximately 10,393 km2 (3,026 square nautical miles) of which about

3,130 km2 belong to the BVI. About 90% of the shelf floor lies in water shallower than 60m.

(200 ft) and it is dotted with coral reefs and rocks with a total slope length of 176 km.

BVI has an Exclusive Economic Zone of 84,050 km2. The area beyond the shallow shelf

belonging to the BVI is approximately 74,813 km2. Several banks rise above the general shelf

floor but the most notable ones associated with fishing are the Barracuda Banks or Sea Mount to

the south east of Virgin Gorda, the Barracouta Banks or North Drop to the north of Jost Van

Dyke (Government of BVI, 2005).

1.3 Fisheries in the BVI

Fishing is an important source of income for some of the people of the BVI as it is for most of its

Caribbean neighbours. However, earnings from fishing contribute a relatively small percentage

to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) when compared with other sectors such as tourism. For

example, in 1991 earnings from tourism (the hotel and restaurant sector) accounted for 10.98%

of the GDP whereas contributions from fishing towards GDP were merely 1.44%. The trend over

the next 5 years was a reduced contribution from fishing and an increase from tourism so that in

1996, the contribution from tourism was 19.66% and that from fishing was 0.73 % (Table 1.1.)

Table 1.1: Contribution from fishing and tourism to GDP, 1991 to 1996

Economic

sector

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996

Fishing

1.44 1.63 1.7 0.73 0.92 0.73

Hotels

&

Restaurants

10.98 11.8 11.39 16.95 17.78 19.66

Source: Development Planning Unit

The three major fisheries contributing to the GDP are the nearshore commercial artisanal

fisheries, the offshore pelagic longline fishery and the recreational fisheries. Fishing licence fees

contribute to the government revenue.

The artisanal fisheries typically employ small boats, less than 25 ft (7.5 m) in length, and

traditional fishing methods such as fish pots, hand line, gill net, seine net, and diving. Most of the

artisanal fishing is carried out on the shelf surrounding the islands. Target fish species are

demersal reef fish, such as snapper and grouper, inshore pelagics, like the carangids and

barracuda, and offshore pelagics, such as tuna, dolphinfish and wahoo. These fisheries also

include invertebrates such as conch, whelk and lobster. The offshore longline pelagic fishery is

limited in size and few boats now operate. The recreational fisheries are classified into the big-

game sport fishery and the pleasure fishery. The big-game sport fishery involves professional

angling aimed at marlin and sailfish with boats of 25 to 50 ft in length (7.5 to 15 m). The

pleasure fishery involves amateur angling, targeting tarpon and bonefish, where vessel sizes

range from 17 to 40 ft in length (5 to 12 m).

The fish resources of the BVI have been divided into five categories: shallow water reef fish,

deep slope and bank fish (e.g. snappers and groupers), coastal pelagic fish e.g. (bonito, blue

runner, yellowtail and mackerel), large pelagic fish (e.g. tunas, swordfish, dolphin, wahoo and

bill fishes) and benthic invertebrates (e.g. crustaceans and molluscs such as lobster, conch and

whelk) (Government of BVI, 1997).

Due to concerns of the CFD over the sustainability of some fisheries, the Virgin Islands Fisheries

Regulations, 2003, include precautionary management measures to protect a number of species.

2

Among these measures are closed seasons. For the Caribbean spiny lobster (Panulirus argus),

the annual closed season extends from March 1st to June 30th. In addition to the closed season,

there are minimum size limits, restrictions on catching berried lobsters, and restrictions on

spearing, hooking and impaling lobsters. The regulations also stipulate that fish traps or pots

must have a biodegradable panel.

According to data collected on the seasonality of fishing gear by the CFD, fish traps are used all

year but the department estimated an average of 40 weeks of use due to weather conditions and

repair time. Other methods such as the use of hand lines, fishing rods and diving also have a

season of an estimated 40 weeks. Horizontal longlines are used for a period of about 22 weeks,

from October to May. Although seine nets can be used all year, there are 2 seasons, from

November to March for jacks, (Selar crumenopthalmus) and from March August for bonito

(Sarda sarda), hardnose (Blue runner/ Caranx crysos) and yellowtail snapper (Ocyurus

chrysurus).

1.4 Socio-economic impact of lobster fisheries management

Enforcement of the closed season for lobster has been resisted by some stakeholders who

reportedly fear loss of income because a major income generating commodity will become

unavailable during the height of tourist season. There are accusations that some of the major

stakeholders were excluded from consultations on establishing a closed season. Stakeholders also

stated that a comprehensive socio-economic survey of the fishery was not done, and this should

be an integral part of the decision-making with regard to the closed season (BVI Conservation

and Fisheries Department, 1995).

Stakeholders mentioned that the information base for the closed season needs to be strengthened.

The requirement for strengthening the biological information base for the lobster closed season is

being addressed by a lobster monitoring programme conducted by the CFD in collaboration with

the fishers. It involves the sampling of catches by fisheries officers on the fishing boats,

sampling of landings at the BVI Fishing Complex, as well as nearshore observation of lobster in

selected habitats.

1.5 Host organisation

The Conservation and Fisheries Department is responsible for all aspects of natural resources

management in the BVI and is divided into five functional units; the Fisheries Unit, the

Environmental Unit, the Environmental Education Unit, the Geographic Information Systems

Unit and the Administration Unit. The goal of the fisheries unit is to ensure that stocks are

maintained at, or are restored to, levels that can maximise sustainable yield given an appropriate

environmentally sound and economically justified effort.

Part of the mandate of the department is to work closely with fishermen to manage the fisheries

resources, to monitor the natural environment and wildlife, to map the natural resources of the

territory, to provide information on the environment to the public and to develop policies and

legislation for managing the natural environment (Virgin Islands Government Gateway, 2006).

1.6 Research objectives

The specific objectives of the project are to:

· Determine the economics of the lobster fishery in respect of expenditure and revenue

· Describe the social importance of the fishery to several categories of stakeholders

3

· Update and expand a previous economic survey to specifically include lobster.

· Establish or strengthen linkages among stakeholders for research on the lobster fishery

through the use of participatory research methods

· Recommend a system of socio-economic monitoring for the lobster fishery

1.7 Organisation of report

The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows: Chapter 2 describes the research methods,

Chapter 3 sets out the results of the fishers and restaurant surveys, Chapter 4 discusses results

and Chapter 5 is the conclusion and recommendations. Questionnaires used are included in the

appendices.

2 METHODOLOGY

The research took the form of a survey of groups of stakeholders, based mainly on two sets of

questionnaires and two focus group meetings. Key informants were also interviewed to get a

background of the fishery and some of the issues involved. Fieldwork was conducted from

August to October 2005 on the four main inhabited islands; Anegada, Tortola, Jost Van dyke and

Virgin Gorda. The investigator was based on Tortola and worked with the staff of the CFD. He

was assisted by another student from the Centre for Resource Management and Environmental

Studies (CERMES), who was also doing research in the BVI. Primary and secondary data were

collected.

2.1 Socio-economic surveys

The socio-economic surveys were directed at stakeholders identified as having an interest in the

lobster fishery. These included fishers and boat owners, the management of restaurants and

hotels, the Ministry of Tourism, the Conservation and Fisheries Department, and the BVI Fishing

Complex. For the purpose of this research, it was decided to select two groups who were directly

impacted by the closed season regulation. One group comprised fishers and boat owners and the

other group was the management of restaurants. Questionnaires were prepared for each to gauge

their dependence on the lobster fishery (Appendices 1, 2 and 3). Other information was collected

from secondary sources and key informants and aimed at establishing background information

on the fishery and on the island in general. In both surveys convenience samples were selected

based on the accessibility of respondents so results may not be representative of the fishery.

2.1.1 Fishers questionnaire

The fishers questionnaire of Pomeroy (1999) along with the SocMon Caribbean guidelines

(Bunce and Pomeroy, 2003) were used to prepare the fishers questionnaire in the present study.

Information was collected on the type of fishing, the income and expenditure in the fishing

operation main sources of income in the fishers' households and the number of dependants of

fishers. The overall goal was to determine the dependence of the fisher and his household on

fishing in general and on lobster fishing in particular. It also provided a sense of his investment

and perhaps indebtedness in the fishery.

The boat owners and fishers to be interviewed were selected from a list of known lobster fishers

provided from the records of the CFD. The list was supplemented with names provided by the

fisheries officers from their personal knowledge, and names were added from records of lobster

landings obtained from the BVI Fishing Complex. The final list contained 55 names and was

believed by the officers to be fairly complete.

4

The fishers were contacted either directly by the fisheries officers to arrange interviews for

administration of the questionnaire or the opportunity was taken to interview them while they

were at meetings scheduled for extension work by the officers. In addition, a few were contacted

on an ad hoc basis when they visited the CFD office. Twenty-seven questionnaires were

administered to fishers on the islands of Tortola, Virgin Gorda, Jost Van Dyke and Anegada. The

interviews were conducted either at the fishers' homes, the CFD main office or at a government

office on Virgin Gorda that was used by the CFD for meetings.

2.1.2 Restaurant questionnaire

The restaurant questionnaire (Appendix 3) was designed to be self-administered. It targeted

operators of independent restaurants and hotels on the same four islands as the fishers

questionnaire. Information was collected on the size of the restaurant, the number of staff

employed, the number of patrons and the amount of lobster sold.

The list of restaurants was mainly compiled from a listing obtained from the publication "BVI

restaurant and food guide", which lists most of the restaurants in the BVI, gives their menus and

quotes the price range for meals. Names additional of restaurants were provided by members of a

fisherfolk organisation.

Thirty restaurants were identified based on them advertising lobster on their menus. These were

selected for an initial list of restaurant stakeholders. A further 12 restaurants were added to the

list from the knowledge of key informants, bringing the total to 42. Questionnaires were sent to a

number of these restaurants but responses to the questionnaires were slow and it was therefore

decided to interview the restaurant managers in person. Of the 42 restaurants identified, 19

establishments were contacted, but because many were temporally closed for refurbishment or

for other reasons, only 11 questionnaires were completed.

2.1.3 Key informants

Formal and informal key informant interviews provided the opportunity to obtain additional in-

depth information on the fishery. They permitted respondents to clarify statements or to further

elaborate on brief comments. Formal interviews were used with the fishers and restaurant

management as well as the manager of the BVI Fishing Complex. The informal interviews were

used with staff from the CFD and the president of the fisherfolk association. Informal interviews

were also used with some of the knowledgeable and experienced fishers for more information on

fishing gear and techniques.

2.1.4 Focus groups

The focus group is a means to evaluate or acquire knowledge of a specific theme. It is basically

an interview of a small number of people (6-10) together and it allows for the gathering of a

great deal of information during one session. The group discussion is led by a facilitator who

draws out and gathers data from people knowledgeable in the field. Questions are posed to start

discussion on the topic. Prior to the session, ground rules for participation are agreed upon with

the participants.

Focus group sessions were held on two islands. Invitations to the first session were made via

announcement on the radios and invitations posted in strategic areas on Tortola. The second was

arranged by the president of the Virgin Gorda Fishermen's Cooperative. The focus group guides

are listed in Appendix 4 and 5 respectively.

5

The first session was held at the CFD located on Tortola. The meeting attendance was low as

only 2 fishers and 2 CFD staff members attended, one of the latter, however, being a part-time

fisherman. The following topics were discussed at the meeting:

· Background on fishers and fishing in BVI

· Threats

· Fish sales

· Laws, regulations, enforcement

· Registration

· Management - who should manage the fisheries

The second, better attended, focus group meeting was conducted on Virgin Gorda with about

eight fishers from that island, members of the Virgin Gorda Fishermen's Cooperative. The

purpose of this focus group meeting was to gain insight into the attitudes and perceptions of the

fishers towards the resource and towards management issues related to specific parts of the

fishers survey.

2.2 Data analysis and interpretation

Questionnaire responses were coded and entered into data tables. Data were analysed using SPSS

for Windows (SPSS Inc.). Graphs and charts were generated in order to facilitate visualization

and interpretation of the collected data.

The SocMon Caribbean methodology calls for validation meetings to be held with socio-

economic assessment participants in order to help confirm and interpret findings through group

discussion and feedback from the data collected. There was insufficient time to hold these

meetings while in the BVI, but it would be useful for the participants to be made aware of the

results set out in this paper. SocMon also calls for identifying key learning and recommendations

for adaptive management. These are included in the conclusions and recommendations.

2.3 Limitations

The methodology sought to avoid or overcome many of the limitations of social surveys. These

are listed below and were taken into account in the generation and interpretation of results.

· Fishers seemed reluctant to take part in the survey due to concern about possible taxation

on their income from fishing, so income estimates may require further validation.

· The refusal of some fishers to be interviewed for unknown reasons may have biased the

sample of respondents.

· Only fishers who were known to the officers and who were comfortable being

interviewed took part, may have introduced bias.

· Fishing is not full time employment for many fishers, and part-time fishers are elusive.

· Not all fishers are registered with the CFD, so unknown full-time fishers may exist.

· Many restaurants were closed at the time the survey was being conducted.

· The small number of people at the first focus group may have reduced the quality or

diversity of data collected during that meeting, but this is not likely.

2.4 Secondary data

Secondary data sources consisted mainly of the records and reports of the CFD, ranging from

fisheries statistics to registration records to the reports of previous studies and consultations. The

information from these sources is included in the results and discussion.

6

3 RESULTS

This section presents the results from the fishers and restaurants questionnaires and from the

focus group meetings. The fishers' questionnaire examines the basics of the lobster fishery;

information on the boats and boat owners; local knowledge of lobster biology; gear used and

fishing effort. Income, operating costs, marketing and boat maintenance are also examined. The

fishers' attitudes and perceptions with respect to the resource and its management are examined

as well. Results from the restaurant survey indicate the status of the business and seasonality of

operation. The focus group meetings produced information that directs attention to the threats to

the species and the industry, and to legislative and regulation issues. These meetings also

produced some recommendations for the lobster fishery.

3.1 Lobster fishery overview

The lobster fishery is one of the commercial artisanal fisheries of the BVI. Most of the fishers

use traps while some dive, both free diving and SCUBA. The traps or "pots", as they are

commonly called, are rectangular and generally made of wire mesh. There are 2 types of mesh

used, a square, welded, plastic coated 2 inch mesh (Figure 3.1) and a galvanised, hexagonal,

twisted, "chicken-wire" mesh of about the same mesh size (Figure 3.2). The frame is usually

made of welded ½ inch diameter "construction" steel rod commonly used in the building

industry. A zinc anode, similar to those used to protect boat propellers from corrosion, is

attached to reduce corrosion. Fishers tie the pots in strings or "slings" of 4 to 8 pots with buoys at

both ends of each string. The use of strings, even though discouraged by the fisheries regulations,

makes it easier to locate and haul the pots.

Figure 3.1: Lobster pot made of square wire mesh

7

Figure 3.2: Lobster pot made of galvanised "chicken wire" mesh and wood frame

The pots can be used for either fish or lobster but according to fishers, some species of fish, such

as triggerfish, attack lobster and fishers say the lobster therefore avoid pots containing such fish.

Fishers therefore target either fish or lobster in a number of ways, which include location, depth,

bait and pot design. The fisher may set the pots in an area known for either lobster or fish and

use bait such as cow skin, to attract lobster. The funnel of the trap for fish is longer and it turns

down towards the centre of the trap, while the funnel of the lobster trap tends to be shorter and

looks inward. In some cases the funnel of the lobster pot may be wide and shallow, to discourage

entry of the deep bodied triggerfish and to give clearance to the lobster's antennae. Some fishers

say that the type of wire and its condition also influence whether triggerfish or lobster enter the

pot.

Lobster caught in the BVI is used mainly in the tourist industry; most is sold to hotels and

restaurants that cater to visitors. There is limited consumption of lobster by the general

population. However, there is a reported increase in consumption during the August Festival.

Fishers also take home small amounts of their catch. Little is exported officially but fishers have

commented that foreign fishers and yachters may be harvesting the resource illegally.

There is a yachting community consisting of visitors from the USVI, Puerto Rico, the USA and

other places who sail either their own vessels, or rented or chartered boats. Their consumption of

lobster is unknown. They are known to buy from the BVI Fishing Complex. The manager of the

complex reported that sometimes a tender from a yacht comes to the complex for lobster but

such sales are recorded as individual sales, with no indication as to who bought them. It has been

suggested that these visitors also purchase lobster directly from fishers and some fishers suspect

that the visitors also fish lobster on their own. A large part of the yachting community comprises

Puerto Rican nationals, and some restaurants report that such visitors come to the BVI in the

summer and on US public holidays and buy large quantities of lobster.

8

3.2 Fishers survey

3.2.1 Demographics

The 27 respondents were male, but that is not to say that they are no female fishers on the

islands. One was present while her husband was being interviewed and she indicated that she

fished occasionally. The president of the Jost Van Dyke Fisherfolk Association is also female.

Fishers and staff of the CFD, however, say that there are only a few female fishers in the

territory. At least one on Virgin Gorda fishes for lobster.

Most of the respondents (66%) are BV Islanders or "belongers". The BVI is a British Overseas

Territory and cannot confer the right of citizenship. The government therefore confers the status

of "belonger" to certain individuals and this carries much of the rights and privileges associated

with nationality in an independent country. Of the others, 15% stated they were not "belongers"

but were of other Caribbean nationalities such as Vincentian, St Lucian and US citizens.

Nineteen percent said they were residents, but they did not volunteer further information on

nationality (Figure 3.3). So a third of the respondents were "non-belongers".

n=27

Non-belonger

33%

Belonger 67%

Figure 3.3: Nationality of respondent

Of those surveyed 63% said they had a fisher's licence, 22% did not have and 19% did not say

(Figure 3.4). The proportion of fishers with licences is slightly higher for "non-belongers" (67%

licensed) than for "belongers" (61% licensed) but the number of responses is small and the large

percentage of non-response needs to be taken into account.

9

70%

n=27

60%

50%

)

%

t

s

( 40%

en

d

n

o 30%

esp

R 20%

10%

0%

Licensed

Not licensed

Didn't say

Figure 3.4: Possession of fisher's licence

The fishers interviewed ranged in age from 33 to 78 years. However, most respondents were 50

to 64 years, with few older fishers (Figure 3.5).

16.0

n=26

14.0

) 12.0

s

(% 10.0

nt

de

8.0

on

6.0

e

s

p

4.0

R

2.0

0.0

30 to

35 to

40 to

45 to

50 to

55 to

60 to

65 to

70 t0

75 to

34

39

44

49

54

59

64

69

74

79

age range

Figure 3.5: Age of fishers

The years spent fishing varied from 5 to 60, and the period spent fishing specifically for lobster

ranged from 5 to 40 years (Figure 3.6). One respondent reported fishing for 60 years. The age at

which respondents started fishing ranged from 9 to 63 years old with a mean of 25.6. The age at

which fishers started to target lobster ranged from 10 to 63 years old but with a higher mean of

29.9. Fishing generally (for species other than lobster) has shown what may be a decline in the

past 14 years, perhaps indicating an increasing concentration on lobster.

10

25

General fishing - n=26

Lobster fishing - n=24

) 20

(%

15

nts

de

on 10

e

s

p

R

5

0

5 to 9 10 to 15 to 20 to 25 to 30 to 35 to 40 to 45 to 50 to 55 to

14

19

24

29

34

39

44

49

54

60

Years fishing

Figure 3.6: Number of years fishing

3.2.2 Livelihoods

Most of the respondents, 89% (24 respondents) said they were the main providers in their

households. Figure 3.7 shows respondents' sources of income besides fishing. The largest group

(34.6%) were those who depended on fishing alone, 30.8% had unspecified occupations and

construction accounted for 19% of the alternative occupations listed. The remaining respondents

were involved equally in farming, hotel, office, and professional work.

40.0

35.0

)

n=26

30.0

(%

25.0

nts

de 20.0

15.0

e

s

pon 10.0

R

5.0

0.0

e

on

urc

ers

ng

mi

office

ional

rism

all oth

far

nstructi

/tou

co

profess

hotel

no other so

Sources of income other than fishing

Figure 3.7: Sources of income other than fishing

The majority of respondents, 61.5%, reported making from 76% to 100% of their individual

income from fishing. Of those remaining, 15.3% made between 51% and 75 % of their income

11

from that activity. For 11.5%, fishing contributed 25% or less, and also 26 to 50% of income

(Figure 3.8).

70.0

61.5

60.0

n=26

50.0

%

s

40.0

dent

30.0

spon

e

R 20.0

15.4

11.5

11.5

10.0

0.0

1 to 25

26 to 50

51 to 75

76 to 100

Percent income from fishing

Figure 3.8: Proportion of income from fishing

Over 70% of the respondents targeted both lobster and fish, while 24 % targeted lobster alone

and 4% targeted fish alone (Figure 3.9).

fish

4%

lobster

24%

both

72%

Target species

Figure 3.9: Target species of respondents

Sixty-two percent (13 of 21) of the respondents who stated their period for fishing lobster said

they fished lobster throughout the year. The others had varying fishing seasons that ranged from

6 to 10 months. One fished from March to June (the current closed season), one in October, five

in November and one in December. They also ended their seasons at different times, two in

12

April, one in May, one in July and two in August. The proportion of fishers operating in each

month peaked in March and was lowest in September (Figure 3.10).

25

n=21

20

)

%

s ( 15

LEGAL CLOSED SEASON

dent

10

spon

Re

5

0

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Figure 3.10: Lobster fishing periods

3.2.3 Vessels

As noted in the 1992 BVI Fisheries management Plan, the majority of vessels are manufactured

in the USA (CFD. 1998.). They are commercially built vessels with brand names such as

"Boston Whaler", "Lindsey" and "Beechcraft". Most are made of fibreglass (91%) but a small

proportion is made of either aluminium or a combination of wood and fibreglass. Boat lengths

range from 17 to 48 ft. (5.18 to 14.63 m). Boats less than 25 ft (7.62 m) generally had outboard

engines, while boats over 26 ft (7.92 m) used inboard engines. Engine horsepower ranged from

40 to 370, with one 48ft boat having two 370 hp diesel engines. Slightly more vessels were in the

range from 100-199 hp (29%) than in the flanking categories (Figure 3.11).

13

35

30

)

n=24

% 25

t

s

(

20

e

n

15

e

s

pond

10

R

5

0

0 to 100

100 to

200 to

300 to

400 to

500 to

600 to

700 and

199

299

399

499

599

699

over

Total HP

Figure 3.11: Range of boat engine horsepower

Figure 3.12 shows the total value of boat and engine of respondents, with the largest proportion

(38.5%) being less than US$25,000 in investment and declining as the value increased.

45.0

38.5

40.0

n=13

) 35.0

%

30.8

(

s 30.0

nt 25.0

de 20.0

15.4

on 15.0

s

p

e

7.7

7.7

10.0

R

5.0

0.0

< $25,000

$25,000 -

$50,000 -

$75,000 -

> $100,000

$49,000

$74,000

$99,000

Value of boat and engine

Figure 3.12: Total value of boat and engine

3.2.4 Ownership, kinship and sharing

Most of the respondents (73%) captained their own boat. Two respondents (7.7%) were boat

owners but did not captain the vessel; one of these did not fish but employed a fisherman instead.

The other did not give full information. Two respondents (7.7%) were captains of boats owned

by others, and 2 of the respondents were crew only (Figure 3.13).

14

80.0

70.0

)

n=26

60.0

%

t

s

( 50.0

n

de 40.0

on 30.0

e

s

p

20.0

R

10.0

0.0

owner/captain

owner

crew only

captain only

Part owner

Status of respondent

Figure 3.13: Status of respondent on boat

Twenty-one respondents fished on only one boat, while 5 fished on more than one vessel, 4 of

these 5 were boat owners. Twenty-five out of twenty-seven respondents gave the number of crew

they fished with. There was a total of 33 crewmen among the respondents; 20 full-time and 13

part-time crewmen. Seven respondents fished with one full-time crewman each, and 6 others

with 1 part-time crewman each. Those with 2 crewmen each were: 4 with 2 full-time crewmen; 3

with 2 part-time crewmen; and one with 1 part-time and 1 full-time crewman. The largest vessel,

48ft (4.63m) in length, had 3 full-time crewmen and one part-time crewman along with the

owner/captain. Four respondents fished alone.

If the 55 fishers named by the fisheries officers were boat owners, and their operations followed

the pattern of the survey, then 93% of these (51) carry crew. The 27 primary fishers who were

surveyed had a total of 33 crewmen; which suggests 67 crewmen added to the total of 55 fishers.

This gives an estimated total of 122 people fishing lobster. There were 20 full time to 13 part

time fishers, using the same ratio suggests that there may be 41 full time and 26 part time crew (

Figure 3.14).

With respect to family relationship, 10 of the

crewmen (30%) are related to the captains. Five

Part tim e crew

fishers each carried 1 son as crewman, 2 of these

22%

sons were full-time and 3 part-time. The other

relatives include 1 brother and 1 nephew as full

Prim ary

fisher/boat owner

time crewmen. In 3 cases the fishers mentioned

45%

that relatives were among the crew but did not

specify the nature of the relationship. Twenty-one

crew members were not related to the fisher and 2

Full tim e crew

respondents did not say if relatives were among

33%

their crew.

15

Figure 3.14: Estimated numbers of crew to primary fisher

Fourteen fishers/boats (58%) used a sharing system of some sort while 10 (42%) did not. Of the

four respondents (16%) who fished alone, only 1 expressed a sharing system in which half of the

proceeds went to the owner/captain and half to the boat. For the others, the actual sharing

systems varied, 5 boats (20%) paid a fixed salary to crewmen, while 2 boats (8%) paid a salary

based on the catch. The others share money in varying proportions to the owner, captain, crew,

boat and gear, with the owner's shares in the range of 20% to 50%, boat shares from 20 to 60%

and crew shares from 20 to 40%. Two boats allocated shares to gear.

3.2.5 Local knowledge of lobster biology

The reproductive process of the lobster allows some observed phenomena to be used to indicate

the spawning season. The male Caribbean Spiny Lobster (Panulirus argus) attaches a

spermatophore to the female. This appears as a dark patch on the sternum of the female called a

"tar spot". A detailed description is extracted below.

Among the spiny lobsters, females can mate only immediately after they have

shed their old shell (moulted) while their new exoskeleton is still soft. In mating,

the male lobster transfers a spermatophore (sperm packet) to the female;

depending upon the species, he may slip the spermatophore into her genital pore,

in which case the eggs are fertilized before they are laid, or may attach a

spermatophore to the outside of her shell, in which case the female scratches the

spermatophore open to release sperm just as her eggs emerge. Regardless of the

system of sperm delivery, female lobsters store sperm (inside or outside their

bodies) until conditions are right for "spawning", or fertilization. The female then

retains the fertilized eggs on her abdomen for weeks or months until they hatch

Females bearing fertilized eggs are called "berried lobsters" or said to be "in

berry" (Bliss 1982, cited in Seafood Watch).

Regarding the biology of the species, 80% of respondents indicated that there is a specific time

when lobsters are berried, 12% stated they did not know and 8% said there was no specific time.

The months named for berried lobsters ranged from March to September with most identifying

the period between May and August as the season.

Forty-four percent of the fishers answering this question indicated that they did not notice a

specific time when lobsters had tar spots, 40% said there was a specific time and the remainder

said there was none. The months that fishers noticed seeing the tar spot varied from February to

December, with most in the period from June to September.

Fifty-six percent said they did not know if there was a specific time when lobsters moult, (shed

their shell) while 28% said there was no specific time. Only 16% indicated there was a specific

time when lobsters moult. From these few, the time given for moulting ranged from January to

August, with most saying from May to August. Some of the respondents stated that they

encounter only small numbers of moulting or "soft" lobsters. These findings are displayed in

Figure 3.15.

16

16.0

14.0

Berried n= 20

)

% 12.0

Tar spot n=10

s

( 10.0

Moult n=4

nt

de 8.0

on 6.0

e

s

p

4.0

R 2.0

0.0

Jan

Feb Mar

Apr May Jun

Jul

Aug Sep

Oct

Nov Dec

Figure 3.15: Times at which differences related to mating are observed

The majority of respondents (45%) indicated that there was a specific time when there were

more male than females lobsters. Forty-one percent indicated that they did not know, while fewer

than 14% stated there was no specific time at which differences in relative abundance of either

sex were observed. For those noting a difference, the predominant months when more males than

females were observed, were from January to September with two peaks, one in April to May

and the other July to September. More females were observed in the months March to April, in

June and the period August to September (Figure 3.16).

6.0

More male n=11

5.0

More female n=11

)

% 4.0

s

(

nt

de 3.0

on

2.0

e

s

p

R

1.0

0.0

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Figure 3.16: Times at which differences in relative abundance of either sex are observed

3.2.6 Catch and effort

Most of the respondents owned their fishing gear (87.5%) while only 12.5 % did not. Forty-six

percent of respondents said they dived while doing any kind of fishing, fifty-four percent did not

dive, and only 8% of all respondents used SCUBA. Information gathered from the focus group

meeting on Virgin Gorda is that divers operate in teams of about 3, one of whom uses SCUBA

while the others do not.

17

Total trip length varied from 2 to 15 hours (Figure 3.17). The largest group of respondents (33%)

were at sea from 4 to 6 hours per trip. The next largest group (28%) were at sea for 7-9 hrs.

Nineteen percent spent less than 3 hours per trip, while at the other end of the scale, a total of

19% made trips between 10 and 15 hours in length. The actual time spent fishing varied from 1

to 8 hours with 58% spending between 4 and 6 hours. About a quarter, (26%) spent 3 hours or

less actually fishing, while 16% fished for 7 to 9 hours.

The majority of respondents (52%) made one trip per week, while 22% made 2 trips and fewer

than 9% made 3 trips in 2 weeks (Figure 3.18). The remaining minority (4%) made as many as 4

trips weekly. Considering, however that some fishers rotated hauling between different groups of

pots, the actual frequency of hauling for over half the respondents was generally once per week,

with about 22% hauling twice per week or more, and another 22% hauling less than once per

week. One individual reported hauling pots about once per month, this is probably in the slow

season when the demand for lobster is low. Fishers reported either hauling less frequently or

leaving the trap doors open in the slow season.

35.0

30.0

)

n=21

25.0

%

(

nts 20.0

nde

o 15.0

e

s

p

10.0

R

5.0

0.0

1 to 3

4 to 6

7 to 9

10 to 12

13 to 15

Trip lengths (hr)

Figure 3.17: Length of fishing trips at sea

18

60.0

50.0

n=23

)

% 40.0

(

nts

de 30.0

on

e

s

p

20.0

R

10.0

0.0

1

>1 to 2

3

4

Number of trips per week

Figure 3.18: Number of trips per week

The total number of traps operated from each boat ranged from 2 to 450 with a maximum of 200

being hauled per trip. The biggest proportion (36%) indicated that they hauled 26 to 50 pots per

trip (Figure 3.19).

40.0

n=22

35.0

) 30.0

%

t

s

( 25.0

n

de 20.0

15.0

e

s

pon

R 10.0

5.0

0.0

1 to 25

26 to 50

51 to 75 76 to 100

101 to

126 to

151 to

176 to

125

150

175

200

Number of Traps

Figure 3.19: Number of traps hauled

Catches of fish from pots ranged from 20 to 300 pounds (9 to 136 kg) per trip with 30% being in

the range 26 to 50 pounds (12 to 23 kg) (Figure 3.20).

19

35.0

30.0

)

n=20

% 25.0

(

t

s

n 20.0

de 15.0

on

p

e

s 10.0

R

5.0

0.0

1 to 25

26 to 50 51 to 75 76 to 100

101 to

126 to

226 to

276 to

125

150

250

300

Average weight of potfish per trip

Figure 3.20: Average weight of potfish per trip

Lobster catches per trip (Figure 3.21) were reported to mostly be in the range of 51 to 100

pounds (23 to 45 kg) with another peak at 176 to 200 pounds (80 to 90 kg).

25.0

n=24

20.0

s

%

15.0

nt

10.0

e

s

ponde

R

5.0

0.0

1 to

26

51

76

101 126 151 176 201 226 251 276 301 326 351 376

25

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

to

50

75

100 125 150 175 200 225 250 275 300 325 350 375 400

Average weight of lobster per trip (lbs)

Figure 3.21: Average weight of lobster per trip

Catch per trap ranged from less than half a pound of lobster (0.5 kg) to over 11 pounds (5 kg) per

trap with a mean of 3.7 pounds (1.7 kg) (Figure 3.22).

20

35

n =23

30

25

%

nts 20

de

on 15

r

e

s

p

10

5

0

<1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Lobster catch per trap (lbs)

Figure 3.22: Catch per trap for lobster

3.2.7 Revenue

Average annual revenue has been calculated for each respondent, based on the estimated

individual catches of lobster and fish along with stated selling prices and trips per week. The

length of fishing season for pots was 40 weeks as estimated by the CFD. This number was used

for those fishing all year. For those fishing part of the year their stated fishing period (if less than

40 weeks) was used. The calculation used was: Average catch per trip x number of trips per week

x average selling price x estimated number of weeks fishing per year, for fish or lobster. The

estimated annual gross revenue for each respondent is shown in Table 3.1 (currency is US$). The

estimated annual total income for mixed fishing operations ranged from $5,400 to $339,700 with

a mean of about $90,400. Thirty percent of the operations had estimated gross earnings below

$30,000, and another thirty percent had gross earnings between $40,000 and $59,000.

Table 3.1: Estimated annual gross revenue from individual fishing enterprises

Annual income

Annual income

Annual income

Total estimated

from fish

from lobster

from other species

annual income

$ 2,500

$ 2,800

$ 5,400

$ 5,600

$ 5,600

$ 5,000

$ 10,000

$ 15,000

$ 6,400

$ 18,000

$ 24,400

$ 4,800

$ 19,600

$ 24,400

$ 5,500

$ 16,800

$12,100

$ 34,400

$ 12,000

$ 25,000

$ 37,100

$ 40,000

$ 40,000

$ 16,000

$ 28,000

$ 44,000

$ 30,400

$ 17,200

$ 47,600

$ 37,700

$ 10,500

$ 48,200

$ 16,000

$ 36,400

$ 52,400

$ 6,000

$ 48,000

$ 54,000

$ 25,000

$ 14,400

$15,400

$ 54,800

21

Annual income

Annual income

Annual income

Total estimated

from fish

from lobster

from other species

annual income

$ 44,000

$ 42,000

$ 86,000

$ 5,000

$ 100,200

$ 105,200

$ 49,500

$ 61,200

$ 110,700

$ 12,600

$ 112,000

$ 124,600

$ 98,200

$ 72,000

$ 170,200

$ 187,900

$ 187,900

$ 82,500

$ 117,000

$ 199,500

$ 43,100

$ 225,500

$ 268,600

$114,200

$ 225,500

$ 339,700

Total from all

$616,400

$1,435,600

$27,500

$2,079,700

respondents

Mean

$ 90,400

Few respondents targeted other species commercially besides fish and lobster. These additional

species were conch and whelk, which were caught commercially only for special orders on

occasions such as the August Festival. The August Festival commemorates the emancipation

proclamation and is celebrated on the first Monday in August. It is the main cultural festival of

the BVI. Many BV Islanders, living abroad, return home to join in the celebration. These visitors

seek the traditional foods which are not normally available overseas, including conch and whelk,

but although lobster is not considered by many to be a traditional delicacy, it is reported that

there is an increase in lobster consumption during the festival.

3.2.8 Maintenance and operating costs

Fuel cost per trip ranged from under $50 to over $200 with most being $51 to $100 per trip

(Figure 3.23).

45

40

) 35

% 30

s

(

nt 25

de 20

on 15

e

s

p

R 10

5

0

0-50

51-100

101-150

151-200

>201

Cost of fuel (US $)

Figure 3.23: Operating fuel cost

Ice is not a major cost for lobster fishers since they keep lobsters alive for sale and need ice only

when catching fish. The most ice carried per trip cost $50 but some fishers carry a single bag of

ice which costs $3 (Figure 3.24). The mode was $11 to $20 per trip.

22

50

45

40

)

% 35

t

s ( 30

e

n

d 25

n

o 20

15

Resp 10

5

0

0-10

11-20

21-30

31-40

>41

cost of ice (US $)

Figure 3.24: Cost of ice per trip

Bait also varied in cost, half of the respondents spent about $40 to $60 in bait while the other half

spent less (Figure 3.25).

60

50

)

% 40

s

(

dent 30

spon 20

Re

10

0

01-20

21-40

41-60

Cost of bait (US $)

Figure 3.25: Cost of bait

Food was not a major expense on most trips since they did not fish overnight. About half of the

respondents spent $10 or less per trip, while one respondent spent as much as $55 for a trip with

2 full time crewmen for an average of eight and a half hours at sea per trip. (Figure 3.26)

23

60

50

)

% 40

t

s

(

en

d 30

n

o

sp 20

Re

10

0

0-10

11-20

21-30

>31

Cost of food (US $)

Figure 3.26: Operating cost of food

The majority of respondents (62%) indicated that boats were repaired or maintained annually and

13% did this twice a year. Equal proportions of respondents (31.8%) reported annual

maintenance costs between $100 and $500, and between $1000 to $1500 (Figure 3.27). The

range between $500 and $1000 accounted for 13.6% of respondents. The remaining respondents

had relatively high annual maintenance costs, nine percent spending in the range of $2,500 to

$3000. Only 25% of respondents had insurance on their boats, 71% did not, while the other 4%

did not know if the owner had insured the boat. The annual cost of insurance ranges between

$500 and $3700.

35

n=22

30

) 25

%

s

(

nt 20

15

e

s

ponde

R 10

5

0

100 to

501 to

1001 to 1501 to 2001 to 2501 to 3001 to 3501 to 4001 to

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

4000

4500

Annual maintenance cost

Figure 3.27: Annual maintenance cost of boat.

24

3.2.9 Marketing arrangements

Fisheries regulations stipulate that unless information to the contrary is gazetted, 60% of catches

from local registered fishing vessels and 80% from foreign vessels shall be landed at the BVI

Fishing Complex or at a landing site agreed in writing with the Complex. However, most of the

lobster (between 90 to 100%) was sold directly to restaurants. Respondents stated that a higher

price and close proximity to restaurants were the main reasons.

Prices ranged from $5.00 to $7.00 per pound with a mean of $6.26. An interview with the

manager of the BVI Fishing Complex revealed that there is limited consumption of lobster by the

general population and he suggested that the price is too high for most householders. The BVI

Fishing Complex buys lobster at $6.00 per pound and sells at $7.00. During the tourism off

season, due to reduced demand from the restaurants, the fishers may drop the price to the

complex to $5.00 per pound. The manager of the complex pointed out that the complex has no

holding tanks and the lobsters are kept in traps over the side of the dock. Postharvest losses are

higher than normal during this extended holding period.

The respondents sold their fish either to the BVI Fishing Complex or directly to customers. The

reasons given for selling to outlets outside of the Complex include custom, convenience and

proximity to the chosen outlets. Some fishers found it easier to sell the fish whole to the

Complex rather than having to clean it for sale to the public even though the price paid by the

Complex may be lower. Some fishers said that they sell to the Complex because doing so allows

them to maintain a relationship with the Complex, whereby they can buy fuel and supplies at

reduced prices and on credit.

3.2.10 Attitudes and perceptions regarding the resource and management

This was a part of the original questionnaire but due to the length, this section was dropped and

only those respondents who were willing to answer the additional questions were asked directly

about the attitudes and perceptions towards the resource and management. The questions were

also asked as part of the focus group session with the Virgin Gorda Fishers Cooperative.

Everyone claimed to be aware of the regulations regarding lobster fishing and rated the

compliance of others with the regulations as generally moderate to acceptable. They rated

enforcement as moderate to minimal.

Concerning the abundance of fish and lobster, most felt that the amount of fish and lobster had

decreased over the past 5 years, from 2000 to 2005. However, with regard to a 10 year span,

from 1995 to 2005, 40% believed there was a decrease in abundance and 30% thought there was

no change. No respondents thought that there had been an increase in abundance over the last 10

years.

Regarding the number of fishers, three of seven respondents said there was an increase in the

number of fishers in the past 5 years, while three others thought there was a decrease and one

thought there was no change in numbers. With regard to any perceived increase in numbers of

fishers over the span of the last 10 years, two respondents said the numbers had not changed, one

said there was an increase in numbers and one said there was a decrease. The other respondent

said he did not know.

Eight of eleven respondents reported an increase in demand for lobster over the past 5 years,

with two stating there was no change. One said he did not know. Five out of 10 who responded,

25

stated that the price for lobster had increased over the past five years, four claimed there was no

change and one said prices had decreased.

3.2.11 Lobster closed seasons and other regulations

Eight of eleven respondents were in favour of a lobster closed season, while the remaining three

were not. Two out of nine said they had been affected by the BVI closed season, and five said

they had not yet been affected but expected they would be. They cited loss of income to both

fishers and restaurants as the negative impact. The preferred period for the closed season was

June or July to October and the frequency of responses given for the months preferred is shown

in Figure 3.28.

120.0

100.0

)

%

80.0

t

s

(

e

n

60.0

e

s

pond

40.0

R

20.0

0.0

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Months

Figure 3.28: Respondents preference for closed season

Declared closed seasons for other Caribbean countries are presented in Table 3.2. The majority

of the closed seasons within the Caribbean range between March and July, within which the

closed season for the BVI falls (March to June). Those countries closer to the BVI, have closed

seasons which start later than the BVI. Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Florida, Bermuda and

the Bahamas all start their season in April. However, Cuba has 2 closed seasons at different

locations on the island, one which starts at the beginning of March and closes at the end of May

and the other which starts in the middle of March and ends in the middle of June. The US Virgin

Islands do not have a closed season for lobster.

26

Table 3.2: Lobster closed seasons in various Caribbean countries

Jan Feb Mar Apr May

Jun Jul Aug

Sept Oct Nov

Dec

Bahamas

Belize

Bermuda

Brazil

Colombia

Cuba

Cuba

Dominican Republic

Honduras

Jamaica

Mexico

Nicaragua

St.Lucia

USA Florida

Venezuela

BVI

Turks and Caicos

Puerto Rico

Grenada

Cayman Islands

Dominica

St Vincent and Grenadines

Source: Adapted from Dilrosun (2000).

All of those who were asked about the new BVI fishery regulations agreed with the restrictions

on size, with at least one commenting that the minimum size was still too small. They also

agreed on the restrictions on the use of spear guns, specifically for lobster, which are normally

sold live. The reasons being that restaurants prefer live lobster and some fishers stated that

lobsters decrease in weight after dying. These respondents also agreed on restrictions on taking

berried lobsters. While six were in favour of the ban on taking moulting lobster, three were

against it and two gave no response. Some suggested that dropping moulting lobster overboard

would be a waste since predators would eat them. Some respondents reported leaving the soft-

shelled lobster in the pots as they dropped them back.

Almost all of these respondents thought that fishers and government should make decisions

together on management issues. Only one thought that management should be by fishers only.

Some stated they did not like government handing down decisions that affected their lives

without consultation. When asked if they had been aware of consultations on the new

regulations, eight said they had, and two said they had not. Even though they claimed to favour

fishers' involvement in management, only two of the eleven were members of a fisherfolk

organisation.

27

3.3 Restaurant survey

3.3.1 Closed restaurants

Of the 42 restaurants identified for the survey, 19 (45.2%) were listed as being closed at some

time during the off season in the publication, The BVI Restaurant and Food Guide, and nine

(21.4%) were listed as being open all season. Only 12 responded to the questionnaire and the

management of others did not return the questionnaire or arrange to be interviewed. The

restaurant closures extended from August to October (Figure 3.29), so in this period lobster

would not be served.

40.0

35.0

)

% 30.0

(

25.0

osed

cl 20.0

r

t

ed 15.0

o

p

e 10.0

R

5.0

0.0

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Figure 3.29: Closure of restaurants

The results are therefore biased in the sense that responses came from restaurants that were open

in the slow (off-peak) season and there were no responses from those that were closed.

Approximately 36% of the restaurants surveyed were in operation between 16 and 30 years,

while another 36% were open between 31 and 50 years (Figure 3.30).

40

36.36

36.36

35

30

)

%

(

s

25

20

18.18

pondent

15

s

e

R

9.09

10

5

0

<15

16-30

31-45

45-60

years open

Figure 3.30: Number of years for which various restaurants were in operation

28

3.3.2 Patrons

Numbers of restaurant patrons or guests varied dramatically between peak and off-peak seasons.

The reported numbers of guests per week ranged from 75 to 2500 in the peak season depending

on the size of the restaurant, while the comparable numbers reported for the off-peak season

were between 10 and 1000. For the peak season, 30% of respondents indicated that they had less

than 100 guests per week at the restaurant, 30% had between 101 and 200 and 30% had over

1000 guests per week (Figure 3.31). The patrons in the off-peak season were between 0.5% and

65.5% of numbers in the peak season, with a mean of 37%.

35

30

)

% 25

s

(

n=12

20

15

pondent

s

e 10

R

5

0

<100

101-

201-

301-

401-

501-

601-

701-

801-

901-

>

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000

1000

N um ber of G uests in peak m onths

Figure 3.31: Number of guests per week in peak season

For the off-peak months, 50% of the restaurant management reported less than 100 guests per

week while ranges between 700 and 800, 800 and 900, 900 and 1000 were reported by 10%

each. (Figure 3.32).

60

50

)

%

n=12

40

s (

nt

30

nde

o 20

e

s

p

R 10

0

<100

101-

201-

301-

401-

501-

601-

701-

801-

901-

>

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000

1000

Number of Guests in off-peak season

Figure 3.32: Number of guests per week in off-peak season

Half of the respondents indicated that their restaurants are closed at some time during the tourist

off season which falls between July and October. Reported lobster purchases (Figure 3.33) and

29

the restaurants reported peak seasons indicate their main business season extends from

November into June.

With regard to purchasing lobster, all restaurants surveyed bought most of their lobster directly

from the BVI fishermen but some also bought from the BVI Fishing Complex occasionally. The

reported cost of lobster ranged from $6.00 to $8.00 per pound. The total monthly restaurants

purchases of lobster for those surveyed are shown in Figure 3.35. Seven respondents (58.3%)

claimed prices remained constant throughout the year and five (41.7%) claimed the price varied.

While this could have given valuable information for determining seasonality the monthly prices

were not given.

500

450

400

350

l

bs) 300

(

ht 250

e

i

g 200

W 150

100

50

0

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Figure 3.33: Average monthly lobster purchases

3.3.3 Tourist arrivals

Records of tourist arrivals to the BVI from 1996 to 2002 indicate an annual peak in March and a

low in September. Figure 3.34 shows average tourist arrivals by month for that period. To the

extent that lobster is mainly for tourist consumption the number of visitors may serve as a rough

proxy for patterns in market demand.

40,000

35,000

30,000

s

val 25,000

e arri 20,000

15,000

Averag 10,000

5,000

0

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec