CERMES Technical Report No 10

Assessing sustainable "green boat" practices of

water taxi operators in the Grenadines

D.T. LIZAMA AND R. MAHON

Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES)

University of the West Indies, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences,

Cave Hill Campus, Barbados

2007

ABSTRACT

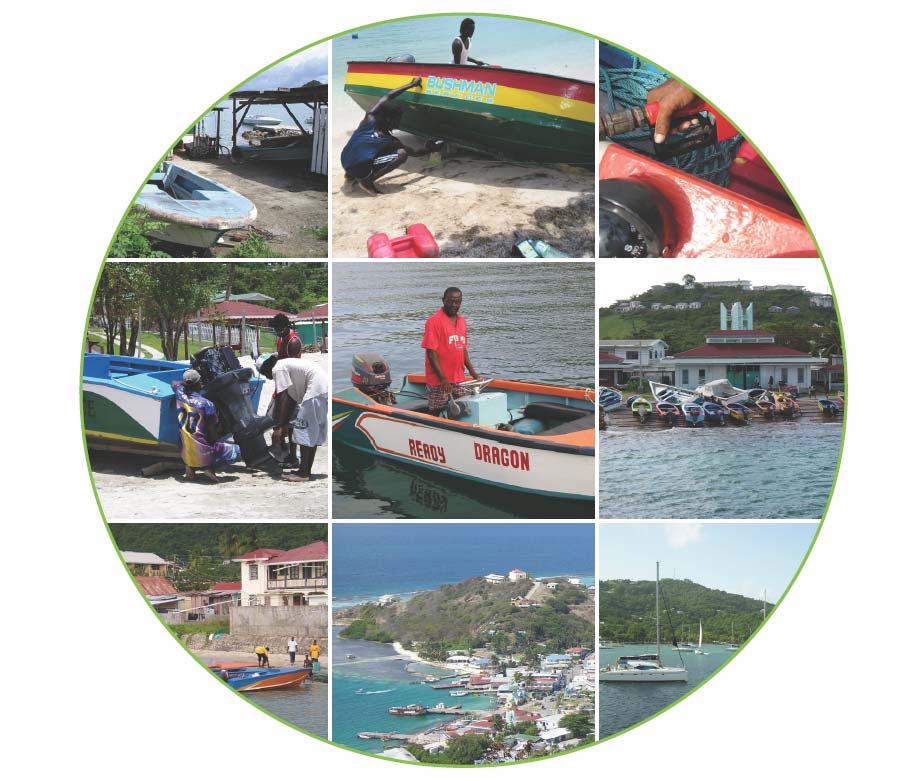

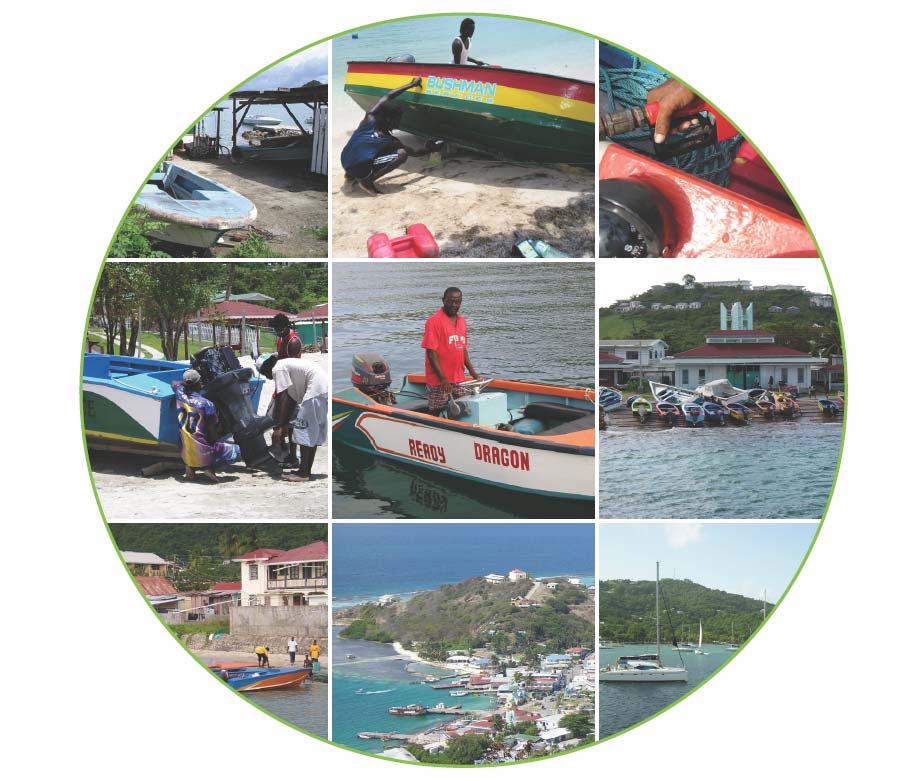

The Grenadines is an island chain in the Windward Islands of the West Indies. The islands are

situated between mainland St. Vincent and Grenada and lie across the boundary of the countries

of St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Grenada. The coastal and marine ecosystems of all the

Grenadine islands are of considerable value to the national economies and quality of life.

Residents depend on the resources for their livelihoods through various activities. Water taxiing

is an important form of employment in the Grenadines that services both the tourism industry

and the local transportation system.

During the development of the strategic plan in Phase 1 of the Sustainable Grenadines project,

building capacity of water taxi operators to provide better customer service and reduce impact on

the environment was identified as a priority. The majority of the water taxi operators from the

islands take their tourists to the Tobago Cays Marine Park in St. Vincent and the Grenadines and

to other areas near Carriacou and Petite Martinique in Grenada that are in the process of being

protected.

Along with tourist arrivals and more frequent, stronger storms, it has been identified that water

taxi operators are also contributing to the degradation of the marine environment in and around

these areas of interest by engaging in non-environmental boating practices. To verify this, a

study was conducted titled, "Assessing sustainable `green boat' practices of water taxi operators

in the Grenadines".

Fifty water taxi operators were randomly selected and interviewed in six Grenadine islands. The

water taxi operators were questioned about their routine boating practices, threats to the marine

environment, the value of the marine resources and measures that should be put in place to

protect them.

Results indicate that water taxi operators' current practices are often not environmentally

friendly. This is evident through improper anchoring, littering, usage of non-environmentally

friendly cleaning agents and equipment, etc. Using the results of the in-depth survey, a booklet

compiling the best environmental practices for boat operation covering several topics has been

drafted for the water taxi operators. Considering the importance of the marine resources to all

stakeholders, the resources need to be protected and laws enforced to ensure intergenerational

equity. Improved boating practices by water taxi operators can contribute significantly to marine

environmental conservation in the Grenadine islands.

Key words: "Green boat", water taxi, Grenadines

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to all who helped me through this study:

To the water taxi operators and other key persons in the community who gave their time, support

and more importantly, information. Without their input, this survey would not have been a

success.

To my advisor, Dr. Robin Mahon, for his patience and guidance. Dr. Mahon, thank you for your

unlimited kindness and words of advice.

To everyone who helped in editing my research paper, many thanks!

To Olivia Carballo-Avilez for translating the abstract to Spanish.

To two dear friends, Bertha and Alexcia for making the summer of 2005 an enjoyable one!

I thank my family and friends for their prayers, support and encouragement throughout the year.

ii

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................

ACKNOLEDGEMENTS.........................................................................................................

1

INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................................1

1.1

BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................................1

1.2

GOAL AND OBJECTIVES...............................................................................................................................2

2

LITERATURE REVIEW..................................................................................................................................3

2.1

PROGRAMMES .............................................................................................................................................4

2.2

REGULATIONS AND GUIDELINES .................................................................................................................5

2.2.1

International ..........................................................................................................................................5

2.2.2

Regional.................................................................................................................................................6

2.2.3

National .................................................................................................................................................7

2.3

ASSESSMENT OF SUSTAINABLE BOATING.....................................................................................................8

3

METHODOLOGY.............................................................................................................................................9

3.1

LITERATURE SURVEY AND REPORT REVIEWS...............................................................................................9

3.2

PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF WATER TAXIS MEMBERS.....................................................................................9

3.3

IN-DEPTH QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY...........................................................................................................10

3.3.1

Data analysis .......................................................................................................................................11

4

RESULT............................................................................................................................................................11

4.1

PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF WATER TAXIS OPERATORS................................................................................11

4.2

IN-DEPTH QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY...........................................................................................................11

4.2.1

Water taxiing as an occupation ...........................................................................................................11

4.2.2

Marine awareness and value of marine resources ..............................................................................13

4.2.3

Threats and solutions...........................................................................................................................16

4.2.4

Service(s) offered .................................................................................................................................18

4.2.5

Anchoring ............................................................................................................................................18

4.2.6

Solid waste...........................................................................................................................................18

4.2.7

Fuel and Oil.........................................................................................................................................20

4.2.8

Engines and engine maintenance.........................................................................................................20

4.2.9

Vessel maintenance..............................................................................................................................23

4.2.10

Education ........................................................................................................................................25

5

DISCUSSION ...................................................................................................................................................26

6

RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................................................................30

7

RERENCES......................................................................................................................................................32

8

APPENDICES ..................................................................................................................................................34

Citation

Lizama, D.T. and R. Mahon. 2007. Assessing sustainable "green boat" practices of water taxi

operators in the Grenadines. Sustainable Grenadines Project. CERMES Technical Report No. 10.

41pp.

iii

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

The Grenadines is an island chain in the Windward Islands of the West Indies. The islands are

situated between mainland St. Vincent and Grenada and lie across the boundary of the countries

of St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Grenada. The 30 islands and cays that comprise the

Grenadine Islands are among the most popular cruising grounds in the Caribbean, surrounded by

coral reefs and clear blue waters ideal for diving, snorkelling and boating

(www.lonelyplanet.com).

The islands in the Grenadines have an interesting history of indigenous Ciboney, Arawaks,

French and British settlers. These settlers mixed with each other giving the Grenadines its unique

mixture of cultures and traditions. During the 1700s alone, it was settled by the British, captured

by the French and then restored to the British in the late 1700s. Of the six islands where this

survey was carried out, Carriacou is the largest island and most developed and Mayreau the

smallest and least developed. Bequia remains the most visited island in the Grenadines due to its

close proximity to mainland St. Vincent. The least visited islands are Carriacou and Petite

Martinique, which only get the tourists that trickle down from the northern Grenadine islands.

The coastal and marine ecosystems of all the islands are of considerable value to the national

economy and quality of life (French Cooperation Programme, 1994). Residents in the

Grenadines have traditionally relied on the sea for their livelihoods; they use it for fishing,

travelling, recreation and other activities. For the residents of the Grenadines, tourism and fishing

are the major activities and income earners. The environment, however, that these industries rely

on has been significantly degraded. The beaches, land and marine water quality have all been

degraded, while the food resources of the land and sea have been depleted.

Most of the Grenadine islands have been struggling with the concept and practices of sustainable

development and this can be attributed to several factors. Islands such as Mustique and Bequia

have taken some of the measures and implemented programmes focusing on sustainability, but

many of the other islands do not have the human or technological resources to put such measures

in effect. Other reasons why this has not been successful include lack of governmental support,

lack of organisations to spearhead such programmes on several islands and lack of knowledge or

information on such initiatives. Examples where one industry (tourism) is causing adverse

effects on the environment and threatening the marine ecosystem of the Grenadines include poor

coastal development, increase in solid wastes, beach degradation, and poor boat operation

practices. There are regulations, conventions and agreements that provide the basis for

developing programmes, measures and alternatives that may be adopted to reverse the situation

in the Grenadines.

The Sustainable Grenadines Project is addressing some of the impacts mentioned above. This

project started in 2002 with the overall goal to promote integrated sustainable development of the

Grenadine Islands for the social and economic well being of the people who live there

(www.cermes.cavehill.uwi.edu). The project has two purposes, which are first to develop a

participatory co-management framework for integrated sustainable development in the

Grenadines and second, to demonstrate participatory sustainable development that can be

adapted by small islands systems. (www.cermes.cavehill.uwi.edu). Phase 1 of the project,

"Stakeholder assessment and participatory project development" was successfully completed in

1

2003. Phase 2 constitutes implementing the participatory strategic plan developed in phase one,

over a five-year period (November 2003-December 2008). It has four focal areas including

continued capacity building of the non-governmental organizations and government

departments; creating networks to develop functioning linkages between stakeholders and

assisting stakeholders in developing proposals to seek funding for other projects.

During Phase 1 of the Sustainable Grenadines Project, participants and partners recognised that

the water taxi operators have the potential to significantly impact the environment throughout the

Grenadines because of their daily activities. The majority of the water taxi members are small-

scale operators who struggle to make a living from the business. They work throughout the

Grenadines providing transportation services to the other islands and charter tours for tourists

and locals in both the high and low seasons. The high season represents high influx of tourists

and plenty business opportunities for the water taxi operators. Low season on the other hand,

represents limited visitors; hence, business declines and some operators revert to other sources of

income. Negative impacts of working at sea daily may arise from poor boat operation practices

such as inappropriate anchoring, grounding on reefs, waste disposal and improper boat

maintenance, among others. Although operators have been using boats to carry out their

activities for years, they have only recently formed and become members of water taxi

associations in the Grenadines. These are the Southern Grenadines Water Taxi Association

(SGWTA) of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, which formed in early 2004, and the Carriacou and

Petit Martinique Water Taxi Association (CPMWTA), which formed in June 2004.

It was during the development of the strategic plan in Phase 1 of the Sustainable Grenadines

project, that building the capacity of water taxi operators to provide better customer service and

reduce impact on the environment was identified as priority. The planning was followed-up

specifically for the water taxi operators in June 2004 in a vision and project-planning workshop

(CEC, 2004). This led to the submission of a proposal to the Global Environment Facility (GEF)

seeking funding for a project to build environmental stewardship through workshops and training

sessions among the water taxi operators from both associations (CEC, 2005). The inception

meeting for this project was held in April 2005.

This study focuses on one of the five components of the Water Taxi Project: "assessing the

sustainable `green boat' practices of water taxi operators in the Grenadines". The aim is to assess

their sustainable boat operation practices and subsequently, inform the operators about their

impacts on the natural environment. This is intended to help the water taxi operators become

better caretakers of the environment and be more capable of passing on the information to their

customers and the public in general (CERMES, 2004).

Finally, the perception of the value of the marine ecosystem to the operators and the knowledge

the operators have about sustainable practices are unclear. This study will also serve to provide

strategic recommendations to address any problems identified. This information will then help to

inform the operators about sustainable practices, while ensuring the protection of the

environment.

1.2 Goal and objectives

The primary goal of this project is to "assess the sustainable `green boat' practices of the water

taxi operators in the Grenadines" and to inform them about ways to improve their boat operation.

The objectives of this project are:

2

(a) To identify the water taxi operators on Union Island, Bequia, Mayreau, Canouan, Petite

Martinique and Carriacou.

(b) To research sustainable boating practices world wide, in the Wider Caribbean and in the

Grenadines

(c) To identify which sustainable practices can be adopted or adapted for the Grenadines

(d) To contribute to the Sustainable Grenadines Project via providing information and

recommendations for green boat operation training for water taxi operators.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The Earth is rich with various types of natural resources. However, the management of these

resources since the early 1960's have been a growing concern throughout the world. This has

been driven by the increasing awareness of the local and global damage that is inflicted upon the

environment as a result of several direct and indirect anthropogenic activities (Goodbody et al.,

2002). It was not until about thirty years later that there was a joint global effort at the Earth

Summit in 1992 that all countries were issued a mandate to protect the environment for the

present and future generations. Since then, the Earth Summit has served as the base for some

important conventions relevant to sustainable development and protection of the natural

resources. The Convention on Biological Diversity among others is of partial interest for this

paper as it seeks to conserve and promote the sustainable use of biodiversity on Earth

(http://www.joburg.org.za/summit/simple.stm). In addition, there are also several marine

conventions, agreements, etc. that seek to conserve the resources of the marine environment.

These conventions and other non-binding agreements are evident on the international, regional

and local levels.

The marine environment is also exposed to many anthropogenic activities, many of which have

significant impacts on coral reefs. Anthropogenic activities such as habitat destruction,

overexploitation and introduction of invasive species all result in species depletion. Humans

then, are largely responsible for this and the overall degrading quality of all ecosystems on Earth.

So then, the management of the resources really means to manage the people and their diverse

and potentially damaging activities whether within their private places or shared resources

(Goodbody et al., 2002). However, for people to fully cooperate with sustainable development

and how to best achieve these goals, they must be sufficiently informed, their livelihoods

understood and the benefits explained.

The growing, unsustainable, tourism industry throughout the Caribbean is to blame for many of

these negative impacts. There are increase water transportation, visitor arrivals, more coastal

construction for hotels, resorts and beach facilities. While these are no different for the

Grenadines, one major factor that the Sustainable Grenadines Project is focusing on is boat

operation in the Grenadines where operators in general, engage in daily activities that degrade

the environment. There are several approaches by many people throughout the world to reduce

the negative impacts by boat operators. This is carried out on several levels of green boating

across the globe. Some examples include clean-up programmes, regulations and guidelines

(international, regional and national), environmental best practices manuals, boat operation and

environmental awareness and education about the entire integrated ecosystems being affected.

3

2.1 Programmes

Support from international and regional organizations are helpful, but interest and initiative from

the countries that need such practices, are usually more effective. There are various countries

throughout the world and region that are promoting sustainable boating practices on different

levels as measures to protect the environment. Some examples that put forth different approaches

to green boating include the environmentally sound boating and marinas: the good mate/clean

marinas partners. This is organised by The Ocean Conservancy in partnership with the United

States and the British Virgin Islands. They are hoping that this will serve as a model for other

Caribbean States.

In California, USA, there is the `Boating Clean and Green Campaign' designed to reduce

pollution from boating and marine businesses. This programme combines boater education

(focusing on environmentally sound boating practices) with technical assistance to local

government and marine businesses. The programme also incorporates a variety of stakeholders

including universities, non-governmental organizations and more. It helps to install services that

reduce oil and fuel spills, sewage discharges, hazardous wastes and marine debris through

absorbent pad exchange programmes, oil-change services that collect used oil for recycling,

bilge-pump outs, plus oil water separation facilities and more (www.ucce.ucdavis.edu).

There have been efforts in Florida and Australia in establishing "clean marina programmes" and

other environmental programmes that aim to protect the marine ecosystem. In Florida, the

Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has established the Clean Marina

Programme (CMP) for marinas, boatyards and boaters. This programme works closely with the

Clean Boating Partnership, where the CMP is having a positive impact on educating Florida's

boat industry and preserving its waterways (www.floridacleanboatingpartnership.com). It

focuses on the recreational aspect of waterway access on topics such as hurricane preparedness,

boat cleaning, boat impact on plant and sea life etc. Education resulting in positive action is the

basis for these programmes.

In Australia, there is also an established "Clean Marina" programme that applies to all yacht

clubs, boat clubs, slips, boatyards and marinas across Australia. The programme supports

Australia's marine industries in all their endeavours, while protecting the waterways

(www.bia.org.au). The programme not only provides rules on valuable environmental practices,

but also rewards benefits. There is also the Boating Industry Association Ltd. (BIA)'s Code of

Practice and the Environment. It demonstrates members' concerns for environmental recreational

boating facilities and services. The BIA also encourages their customers to follow the rules set

out in part seven (7) of the code, whereby it discusses responsible boat navigation, maintenance,

and preventative actions by each individual to maintain clean water and minimise the near shore

water based recreation (www.bia.org.au). Through the BIA there are also many programmes that

focus on environmental practices such as "Best Management Practice for Marinas and Boat

Repair Facilities"; "Project Anchor"; and the "Pollution Reduction Programme".

These programmes can be adapted to suit the situation in the Grenadines. The CMP could be

beneficial to the islands especially Carriacou since the new marina is in the construction phase.

Other environmental programmes that seek to inform boat operators about their malpractices

while protecting the environment are vital as operators can see value in changing their boating

practices for the protection of the resources on which they depend.

4

2.2 Regulations and Guidelines

2.2.1 International

Several international organisations' objectives, goals, meetings, conventions and agreements

address impacts, mitigations, adaptations etc., concerning negative impacts on the marine

environment by marine vessels; however, only one focuses on small crafts. All aim to: protect

international waters from pollution (liquid and solid), reduce loss of marine biodiversity, ensure

that information is shared globally and to ensure that support is provided. Some international

examples include:

1. The International Maritime Organisation (IMO)

2. The International Convention for the Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78)

3. World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD)

4. Jakarta Mandate

5. Convention on Biological Diversity

An example of an international organisation that addresses such issues is the International

Maritime Organisation (IMO), which is one of the responsible international organisations for

improving maritime safety and preventing pollution to water and air from marine vessels. The

IMO also serves as the Secretariat for the International Convention for the Pollution from marine

vessels MARPOL 73/78. In 1996, the IMO also took on the role as leader to ensure that other

international organisations and programmes coordinated the development of the global

programme of action clearing house mechanism with respect to oils and marine litter. MARPOL

is the international convention aimed at controlling pollution from the shipping sector. It has five

annexes that cover specific kinds of pollution and Annex V deals with garbage and litter

(www.marine-litter.gpa.unep.org). In Annex V, the Wider Caribbean Sea and regions along with

the North and Baltic seas were designated as "Special Areas". The disposal of all garbage

especially plastics, into these areas is strictly prohibited.

The World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) held in Johannesburg 2002 re-

emphasised Agenda 21. Agenda 21 is a comprehensive plan for global, national and local action

by organisations of the United Nations, governments and major groups in every area where

humans impact the environment (www.marine-litter.gpa.unep.org). Chapters 17 and 21 of

Agenda 21 pertain to bodies of salt water and solid waste disposal, respectively. These are the

heavily impacted areas many depend on and therefore raise several issues. Chapter 17 discusses

the protection, national use and development of their living resources. Chapter 21 deals with

solid waste disposal (domestic refuse and non-hazardous waste) that may be in large or small

quantities.

The Jakarta Mandate on Marine and Coastal Biodiversity is a subunit of the Convention of

Biological Diversity (CBD), which is a global consensus on the importance of marine and

coastal biological diversity. The CBD aims at promoting the conservation of biodiversity; the

sustainable use of its components; and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the

utilisation of biodiversity resources.

5

The only international agreement that outlines specific guidelines for small crafts is Safety of

Life at Sea (SOLAS), but since it addresses safety regulations, it is beyond the scope of this

paper.

Some of the international organisations, meetings and conventions discussed here all seek

environmentally sound waste management. This however, should not be concerned only with

safe disposal or recovery, but also with the root cause of the problem.

2.2.2 Regional

On the regional "Wider Caribbean" scale, the Caribbean Sea is protected by most of its coastal

countries. There are also several regional organisations, conventions, programmes and action

plans that apply to the Caribbean region for protection of the Caribbean Sea from litter, habitat

destruction, discharge, inter alia. Over the past ten years this has especially been the focus for

Small Island Developing States (SIDS). The SIDS Plan of Action has now been adapted for

developing countries. So far, there has been a lot of progress for some developing countries, but

rather than laws, there are more organisations, actions plans, and programmes that have been

formed, implemented and adopted.

Some regional examples include:

1. Cartagena Convention

2. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)- Regional Seas Programme

3. Global Environment Facility (GEF)-International Waters Project

Source: (www.marine-litter.gpa.unep.org).

The Cartagena Convention - Convention for the Protection and Development of Marine,

Environment and Wider Caribbean -- is binding. It is a convention that entered into force in 1986

for achieving sustainable development of coastal and marine resources in the Wider Caribbean

region through effective integrated management that allows for increased economic growth. The

convention covers various aspects of marine pollution and requires that the contracting Parties

adopt measures aimed at preventing, reducing and controlling pollution from ships, dumping,

and land based activities among others (www.cep.unep.org/). In addition, the Parties to the

convention take measures to preserve fragile ecosystems (like coral reefs and seagrass beds), as

well as habitat depletion, threatened or endangered species and develop technical and other

guidelines.

An example of a regional programme is the Caribbean Environmental Programme (CEP), which

was established under the UNEP regional seas programme by the diverse states and territories of

the Wider Caribbean to collectively address the protection and development of coastal areas

using the framework known as the Caribbean Action Plan, which was established in 1981. The

UNEP regional seas programme, which was initiated in 1974, focuses not on the mitigation and

elimination of the consequences, but also on the causes of environmental degradation as a global

programme implemented through regional components (wwwv.marinelitter-gpa.unep.org). The

programme also focuses on solid waste and marine debris and oil and litter as major issues in the

region. The CEP has four sub programmes, namely Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife

(SPAW), Assessment and Management of Environmental Pollution (AMEP), Information

Systems for the Management of Marine and Coastal Resources (CEPNET) and Education

Training and Awareness (ETA). Although each sub-programme has different objectives, a

common goal is to regionalise the global conventions, agreements etc., for the Caribbean region,

6

through coordination, sharing information, data networking, and improving the research and

technical managerial capacities to address environmental issues adequately

(www.cep.unep.org/).

The GEF international waters project is in progress, but has not yet been approved. This is the

sustainable management of the shared marine resources of the Caribbean's large marine

ecosystem and adjacent regions. Some objectives of the project include implementing legal

policy; policy and institutional reforms (regionally and nationally) and to improve shared

knowledge base so that sustainable use and management of the transboundary living marine

resources will be possible and more abundant.

2.2.3 National

St. Vincent and the Grenadines has only recently considered putting regulations in place for

small boat operators. The SGWTA held discussions with the Port Authority, Tourism Authority

and the Coast Guard about measures that should be put in place for the safety and certification of

small boat operators (Smith, personal communication). To date, these have not even been

drafted. The only official action that has taken place is the registration of the SGWTA. It was

registered in 2004 as a non-profit organisation under the Company Act of 1994, sections 5 and

329 (Smith, personal communication). A constitution was then developed for the SGWTA,

which explains the duties of the executive committee, resignation and removal of members,

projects and activities, publications, meetings and many more important matters relating to this

body. The SGWTA has developed some rules and regulations that all water taxi operators should

abide by while operating their boats in the Grenadines. It is noted however, that not all operators

recognise or respect these rules and regulations and therefore they must be revised. The SGWTA

executive members hope that these new rules and regulations can be implemented and enforced

in the near future (Smith, personal communication).

It may have also been beneficial for the government of St. Vincent and the Grenadines to

implement the mandatory provision of the IMO and the International Ship and Port Facility

Security Code in 2004. It is a new, comprehensive security regime that seeks to establish an

international framework of co-operation between governments, government agencies and the

shipping and port industries in order to detect and take preventive measures against security

incidents affecting ships or port facilities used in international trade1. This however has not been

done and the coastguards seldom patrol the Grenadine waters. On the other hand, using the

National Environmental Management Strategy Plan for St. Vincent and the Grenadines the

government agencies have various jurisdictions of environmental management and addresses

several environmental issues, but due to lack of proper management, effective enforcement and

awareness2, but water taxi operators, among others, who depend on the sea's resources continue

to destroy and pollute the waters intentionally and unintentionally.

The Grenada Ports Authority is the official licensing authority for all water taxis operating in

Grenada, Carriacou and Petite Martinique. The water taxis are separated into two categories

(inshore and charters) and must meet certain requirements in order to get a license and operate.

Unlike the SGWTA, the CPMWTA has not drafted any rules and regulations for the water taxi

1 (http://www.imo.org/Newsroom/mainframe.asp?topic_id=583&doc_id=2689#code)

2http://72.14.203.104/search?q=cache:AK4qricmMf8J:www.oecs.org/esdu/documents/Nems/SVG%2520NEMS%2

520Final2%252019Apr04.pdf+Environmental+Laws+of+St.+Vincent+and+the+Grenadines&hl=en&gl=bz&ct=cln

k&cd=5

7

operators. This is something that they are working on for the future (Bethel, personal

communication). The government of Grenada has already implemented some measures to ensure

sustainable boating practices, but they concern only safety issues. In the future under SOLAS, all

boaters will be required to have distress flares, first aid kit, engine repair tools and VHF radio.

Also, starting 2008, the Grenada Ports Authority has stated that they will not issue licenses to

water taxi operators with gasoline engines. All water taxi operators will be required to have

diesel engines by that time (CERMES, 2004). Apart from that Grenada has about 40 pieces of

legislation that govern the protection and management of Grenada's biodiversity and addresses

environmental management and protection. Water taxi operators in Grenada among other users

of the environment continue with the same non-environmentally friendly practices due to the

lack of effective enforcement of existing legislations and at mitigating adverse impacts on the

environment. In addition, general lack of awareness and understanding of the value, sustainable

use and the need for immediate conservation of natural resources by decision makers and

stakeholders and other identified gaps in the legal system3, also contribute to such practices.

2.3 Assessment of sustainable boating

The most useful literature on assessments of sustainable boating was from other parts of the

world than the Caribbean and it is suggested that the Grenadine boat operators adopt the

environmentally friendly boat practices. Several assessments that were conducted throughout the

world looked at the following main issues and the best practices for each. These include general

vessel maintenance, anchoring, waste disposal, education of the water taxi operators and

passengers, engine maintenance and fuel/ oil. It is quite possible that boat operators and other

users of the marine environment can adopt these best practices and therefore start minimising the

negative impacts occurring throughout the Grenadines.

The Maryland Department of Natural Resources (Maryland Clean Marine Initiative for

Chesapeake Bay) in the United States has a manual that they developed for boaters using the

Bay. This guide discusses the issues, the legal setting as it is in the United States, and best

management practices for each issue. For example, for vessel maintenance, it explains the effects

of each stage of refurbishing namely sanding, washing, and painting and outlines the best

practices (www.dnr.state.md.us).

The Centre for Environmental Leadership in Business (CELEB), Coral Reef Alliance (CORAL)

and Tourism Operators Initiative (TOI) together have also developed a manual as a practical

guide detailed with best practices for all users of the marine environment. Some of the topics

discussed include anchoring, boat maintenance, boat operation, viewing marine wildlife, waste

disposal and more. It also has a self-assessment checklist whereby operators; owners of marinas

and other users of the marine environment can evaluate themselves based on the daily activities

they carry out. The manual discusses each issue and explains why people should care about such

issues and suggests some best practices that should be followed at all times (CELB, et. al., 2001).

The Australian government has outlined its own best practices that boaters must practice while

operating in and around the great Australian barrier reef. Their guidelines also discuss several

activities that affect the marine environment and the best practices that boaters can follow or

implement (www.gbrmpa.gov.au).

3 http://72.14.203.104/search?q=cache:HVp4ruym5mgJ:www.biodiv.org/doc/world/gd/gd-nr-01-

en.pdf+Environmental+Laws+of+Grenada&hl=en&gl=bz&ct=clnk&cd=6

8

Other sources of information concerning green boat practices include websites and online groups

that the researcher was subscribed to. These include the Sustainable Grenadines yahoo group, the

CAST group, MBT (Marine Based Tourism) group, Ocean Journal for environmental managers,

and several websites.

3 METHODOLOGY

The research comprises four parts:

· Literature survey and review;

· Preliminary survey of water taxi operators;

· In-depth questionnaire survey of the sample of water taxi operators;

· Data analysis.

3.1 Literature survey and report reviews

Programmes, training and other best environmental practices for boat operation developed in

different countries were reviewed and compared with those of the Grenadines. Best practices for

sustainable boating practices have been implemented worldwide; these have been researched and

reviewed to determine if they are applicable and adaptable to alleviate the non-environmental

boat operation in the Grenadines.

Laws, conventions and protocols such as those mentioned in the literature review were also

reviewed to determine which ones apply to the activities of small boat operators. These may be

helpful in the Grenadines where they can be adapted and implemented or used to amend the

currents laws concerning boating throughout the islands.

Meetings/interviews with key informants were carried out with the water taxi associations'

presidents, the secretary and manager of the Sustainable Grenadines Project, members of the

Carriacou Environmental Committee (CEC) and Ms. Susan Mahon, manager of Counterpart

Caribbean. Information gathered through the interviews with these various people was used as

background information to determine the variables that were researched and to understand their

concerns of the boating activities.

In addition, information from the literature survey and review suggests that the Caribbean region

is behind in implementing and in some cases enforcing the necessary environmental laws that

relate to protection and conservation of the marine resources. The Caribbean is also behind in

adopting techniques, taking measures and making the general public aware of such

environmental issues that people can associate with. Many reports show that other countries,

usually the developed, first world countries have addressed the issues on a larger global scale

that many underdeveloped and developing countries cannot adhere to or take part in. As a result,

the countries including St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Grenada are now struggling to

understand the concept of sustainable development through `green boat' practices on a smaller

scale and are aiming at localising the efforts to reach that of developed countries.

3.2 Preliminary survey of water taxis members

The preliminary survey was carried out on the islands of Union Island, Bequia, Canouan,

Mayreau, Petite Martinique and Carriacou. This initial survey was a collaborative effort between

Alexcia Cooke and the researcher since both were interviewing the same group of people. Her

researched focused on "A livelihoods analysis of the water taxi operators in the Grenadines".

9

Both persons worked together to develop the questionnaire (Appendix I) and shared the effort of

administering them to the water taxi operators throughout the Grenadines. The preliminary

survey was conducted throughout the islands to find out who were water taxi operators; members

of the two water taxi associations; and to establish contacts and beginning to understand water

taxi operators and their business. Other basic information about the boats such as length, type of

boat, type of engine and boat name among other things was also acquired. To find out how many

operators there were on each island, the researchers used the "snowball approach" asking each

water taxi operator that was interviewed to name others and the location on the island where they

could be found and so on, until no new names came up. On Bequia and Carriacou, significant

members in the community associated with the water taxi operators, suggested to them that they

meet with the researchers. A total of one hundred persons were interviewed from across the

islands for this preliminary survey.

This first survey also served as an icebreaker for the water taxi operators, because all were

informed about the second survey. After the sample size was determined many from each island

were re-interviewed for the in-depth survey. The timeframe for this preliminary survey was

approximately eight days to cover all the islands. After the preliminary survey was completed, all

the data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS).

3.3 In-depth questionnaire survey

Of the one hundred water taxi operators that were initially identified and interviewed throughout

the Grenadines, a fifty percent (50%) sample was taken; only 47 were successfully interviewed,

which represents a confidence of ninety-five percent (95%) confidence interval and error level of

six (3.5%). Ninety-five percent (95%) is used as the rule of thumb when it is difficult to

determine confidence interval or error level of the results. Using the confidence interval, sample

size (50 respondents) and number of completed interviews, the error level was calculated using

the online "random sample calculator".4 These fifty (50) people were spread across all the

islands by means of a random selection using Excel Data Analysis tool. Other respondents were

selected as back-up in the event that those persons who were randomly selected could not be

interviewed. For this in-depth survey, the fifty water taxi operators served as the representative

sample of all water taxi operators from Union Island, Bequia, Mayreau, Canouan, Petite

Martinique and Carriacou using a more in-depth questionnaire. The number of persons that were

selected for a re-interview for each island is as follows: Union Island (20); Bequia (8); Canouan

(1); Mayreau (7); Petite Martinique (5) and Carriacou (10). The number of back-up respondents

used from each island is as follows- Union Island (3); Mayreau (1) and Carriacou (2). Each

person with a contact number was called before departing for the island to verify if they would

be available on the suggested day. Others were informed of our return by personal

communication with the researcher or through their colleagues.

The in-depth survey was also conducted by means of an administered questionnaire (Appendix

II). The questions in this survey focused on several issues concerning boating practices that the

water taxi operators carry out daily in the Grenadines. The structure of the questionnaire

included open-ended, close-ended and selection questions. It covered subheadings such as

coastal and marine activities, attitudes/perceptions of the marine environment and environmental

practices, threats/problems to the marine environment etc. The variables for the questions in this

4 http://www.custominsight.com/articles/random-sample-calculator.asp

10

questionnaire were drawn from various sources found during the literature review. The estimated

time frame for this second survey was approximately nine days to cover all the islands.

3.3.1 Data analysis

The questionnaires from the in-depth study were reviewed to ensure all the questions were

completely answered before the analysis started. The information for each water taxi operator

was entered into a Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) database in "data view" as the

first part of the electronic analysis. The data was then transferred from SPSS to an Excel

spreadsheet to facilitate the analysis.

4 RESULT

4.1 Preliminary survey of water taxis operators

The preliminary survey covered basic information about the water taxi operators across the

Grenadines and served as background information about each water taxi operator in reference to

their boat name, boat size, boat type, engine type and engine horsepower, among other variables.

This information was then used as the basis to develop the questionnaire for the in-depth

questionnaire and to begin understanding the water taxi operators from each island and their

preference in boats. This activity is reported on fully by Cooke et al., 2005.

4.2 In-depth questionnaire survey

Of the fifty water taxi operators (representing a 50% sample size) that were randomly selected

from those identified in the initial survey, only forty-seven were successfully interviewed. Some

questions did not apply to the water taxi operators in Bequia because they do not have a water

taxi association. Lastly, as expected, there were questions that some water taxi operators

deliberately did not answer for the fear of being identified or because they did not think it was

appropriate to reveal the malpractices of other water taxi operators.

Union Island has the largest number of water taxi operators and the largest number that are

registered. This may be attributed to the association having its own constitution under the laws of

St. Vincent and the Grenadines. As a result, most of the water taxi operators that were re-

interviewed came from Union Island. Bequia and Carriacou both had eight people, followed by

Mayreau with seven people, Petite Martinique with five and Canouan with only one person

(Table 4.1). Majority of the water taxi operators were a member of a water taxi association with

SGWTA having the most registered members. Bequia presently does not have a water taxi

association and it seems that there is interest in forming one, but the idea is controversial.

Using the results of the in-depth survey, a booklet compiling the best environmental practices for

boat operation covering several topics has been drafted for the water taxi operators. It is expected

that the operators will work together in unison with personnel from the Sustainable Grenadines

Project and with each other to modify the drafted booklet to suit them.

4.2.1 Water taxiing as an occupation

Twenty-four respondents fall within the 31-40 yrs age group with half having completed primary

and secondary level education respectively. Eighteen respondents (38%) have been water taxi

operators for more than ten years falling in the 11-20 yrs range and with an even amount of 13

respondents being operators for less than five years and between 6-10 years. Three water taxi

operators completed tertiary level education. These three people and the majority of those who

had completed secondary school were from either Carriacou or Petite Martinique (Grenada).

11

Contrary to what some water taxi operators say, water taxiing provides many of the respondents

with the most income. The graphs below show that water taxiing provides the highest proportion

of income for people whether it is their primary (Figure 4.1) or secondary job. Figure 4.2 shows

that there are many who do not have a second occupation and rely on water taxiing alone.

Fishing also ranks high as an

50

occupation that provides

45

high income. Others who

40

have yet a third job are only

ops 35

a few and the choices vary

T

W 30

from artist, security officer

of 25

and mooring renter.

t

age

20

r

c

en 15

e

P

10

5

0

wa s

tr

r

r

p

m

fi

c

b

b

a

a

d

t

c

e

e

r

s

a

u

e

r

p

o

e u

u

s

a

o

e

h

r

i

a

t

a

n

r

c

t

l

p

c

p

l

is

b

k

a

i

d

c

r

'

t

e

e

h

n

e

t

t

t

a a

in

u

s

r

a

g

n

e

h

s

m

k

x d

g

r

t

t

n

t

r

b

n

i

a

a

y

e

n iv

n

t

ic

ry

a

n

o

g in

m

w

g

teu e

rb

t

r

an

r

a

e

e

g

q

n

e

u

ta

r

e

l

Figure 4.2: The occupations that provides the highest proportion of income for water taxi operators

50

45

40

s

op 35

T

W 30

25

20

r

c

e

n

t

a

ge of

15

Pe 10

5

0

art b c e f

f

n

r

s

s

w

w

w

i

i

o

e

s u

o

n

s

r

o

n

e

u

a

e

in

t

i

n

g

h

e

n

l

p

l

t

l

t

ld

d

( d

s

i

in

s

e

f

e

e

p e

t

n

g

t

m

is

r

r

in

s

a r

ru

e

ry

o

h

m

t

g

u

i

e

a

n (b

c

r

o

o

a

x

rf

t

t

i

r

r

i

i

o

i

n

f

k

i

n

n

a

o

g

fi

in

e

in

g

g

t

n

c

g

t

g

)

s

e

s

i

o

n

)

r

wn

s

e

tr

r

u

c.

Figure 4.1: The occupations that provide the second highest proportion of income for water taxi operators

12

Mayreau, Carriacou and Petite Martinique are the islands where occupations other than water

taxiing provide the highest proportion of income (Table 4.1). Fishing provides more or about the

same income as water taxiing in two of the islands. Unlike Union Island and Bequia, WTops are

making a decent living from being water taxi operators, as it is their main source of income.

4.2.2 Marine awareness and value of marine resources

Each water taxi operator interviewed was fully aware that the Tobago Cays is a marine park. Of

the 47 respondents, only one water taxi operator said that he does not respect the Tobago Cays as

a marine park.

More than 50% of the water taxi operators were aware of the rules and regulations (all and some

combined) for the Tobago Cays Marine Park (TCMP) and of these, 25% said that they did not

know all the rules. On the other hand, 46% of the water taxi operators said that they were totally

unaware of the rules and regulations of the Tobago Cays Marine Park (TCMP) put forth by the

SGWTA (Table 4.2).

46% of water taxi operators believed that their colleagues respected the TCMP while 40%

believed that the water taxi operators did not respect the Tobago Cays as a marine park. 12% did

not know if the majority of other operators respected the park (Table 4.3).

13

Table 4.1 Cross tabulation of Grenadine Islands and jobs that provide the highest proportion of income

Grenadine

Islands

Occupations Bequia

Canouan

Mayreau

Union Petite

Carriacou

Island

Martinique

Apartment

1

rentals

Artists

1

(painting)

Beach

1

barbeque

Builder

(boats)

1

1

Builder

2

(houses)

Carpentry

1

Fishing 2 3 1

3

Boat

mechanic

1

Property

1

manager

Real

estate

1

Restauranteur

1

Scuba

diving

1

1

Trucking

1

Water

taxiing

5

1 3 9 2

2

Don't

know

1

Percentage of

22.7 4.5

13.6 40.9 9.1

9.1

WTops

TOTAL

17.0 2.1

14.9 36.2 12.8

17.0

(percentage %)

TOTAL

8

1 7 17

6

8

(WTops)

Table 4.2 Frequency and percentage of water taxi operators' awareness of the

rules and regulations of TCMP

Response Frequency

Percent

Yes 13

27.7

No 22

46.8

Not all

12

25.5

Total

47

100.0

Table 4.3 Frequency and percentage of water taxi operators' respect for the TCMP

Response Frequency

Percent

Yes 22

46

.8

No 19

40

.4

Don't know

6

12.8

Total 47

100.

0

14

The majority (55%) said that the park should not be zoned and one person had no opinion on

zoning the park (Table 4.4). Of the 26 respondents who thought the park should not be

zoned, 24 gave a reason why. Most were of the opinion that the park should remain open to

the public with everyone having equal access to the park and its resources (Table 4.5).

The majority of the water taxi operators expressed that they highly valued the marine

environment because they depended on the resources for their livelihood. Many said the

marine environment's beauty interests them and that tourists come to see the natural

attractions. Only two persons said that they value the marine environment as an area that is

kept safe for water taxi operators and tourists (Table 4.6).

Table 4.4 Frequency and percentage of water taxi operators' opinion on zoning TCMP

Response Frequency

Percent

Yes 20 42

.6

No 26 55

.3

Don't know

1

2.1

Total 47 100.

0

Table 4.5 Frequency and percentage of water taxi operators' reasons for not zoning TCMP

Response Frequency

Percent

Free full public access

20

42.6

It would create segregation

4

8.5

Not applicable

19

40.4

No response

4

8.5

Total

47

100.5

Table 4.6 Frequency and percentage of water taxi operators' perception of the value of the

marine resources

Response Frequenc

y

Percent

Dependent on the resources for livelihood

24

51.1

Natural attraction for water taxi operators and tourists

20

42.5

That the area is kept safe for water taxi operators and tourists

2

4.3

No response

1

2.1

Total 47

100.0

Only two respondents (4%) did not know that the marine environment serves many roles and

functions to both humans and marine organisms. All other forty-five persons (95%) said that

they were aware that the marine environment has different roles and functions to all life that

depends on its resources.

Only nine (19%) water taxi operators were not aware that certain boating activities/practices

could be harmful to the marine environment. Only one of these nine persons, although

unaware that some practices were harmful, did not express interest in learning more about

environmentally friendly boating practices. The other 46 respondents were enthusiastic that

they could learn more about boating and in the process learning to take better care of the

environment on which their livelihood depends. After understanding that certain boating

practices could cause potential damage and being informed that keeping their boat in the best

15

conditions can reduce such negative impacts, 46 respondents said that they were willing to

upgrade their boats.

4.2.3 Threats and solutions

This section reports on the perceived threats and possible solutions to the negative impacts on

the marine environment as stated by the water taxi operators throughout the Grenadines.

More than half the water taxi operators have observed other water taxi operators doing

activities/practices that could potentially harm the marine environment. Although some

claimed to have seen other water taxi operators in the act, many declined to say what they

actually saw. The leading responses from those who did respond were littering and speeding

in the harbour.

Table 4.7: Frequency and percentage of water taxi operators that prefer to use the

The average

different entrances to the Tobago Cays Marine Park

speed that

Entrance Frequenc

water tax

y

i

Percentage

operators

Horseshoe back reef (east)

2

2.1

drive when

Petite Bateau (west)

2

2.1

approaching

Petite Ramadal/Baradal (north)

13.4

28.6

harbours or

Jamesby (south)

22.3

47.6

beaches is

six knots,

Do not go to TCMP

9.2

19.5

but majority

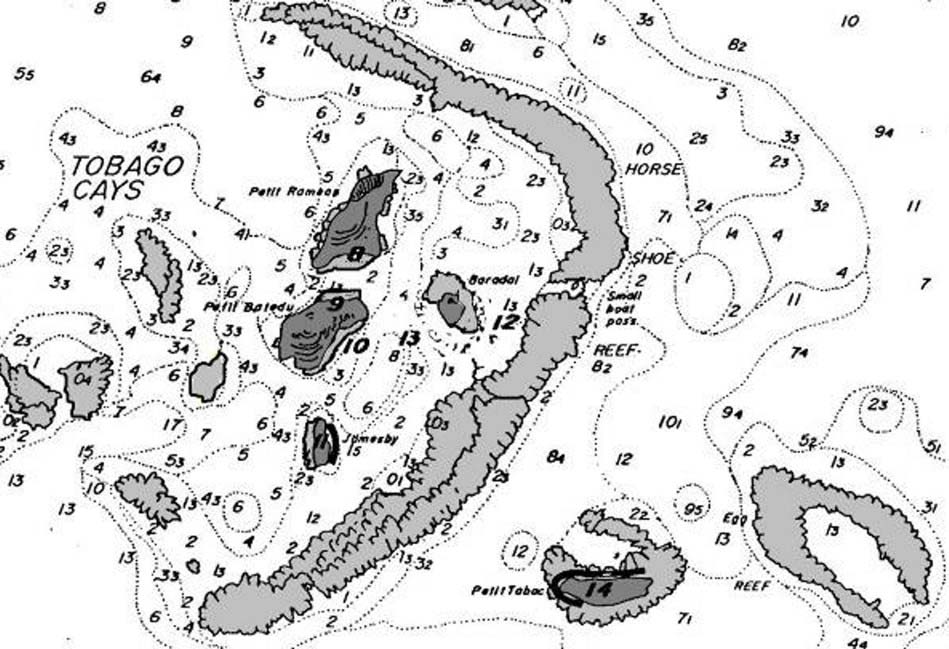

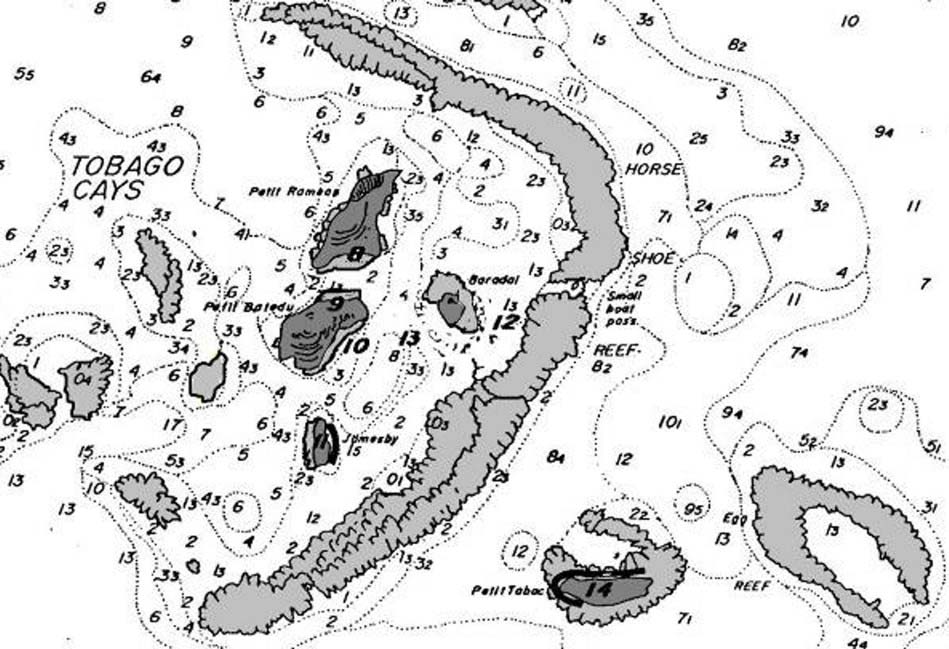

said they drove at a consistent five knots in these areas. In respect to deeper waters, they

drive much faster but say they do slow down when approaching the reefs. Many patch reefs

surround the Tobago Cays, but water taxi operators are keen on using the areas with few

reefs with channels that will take them through to the Cays. The map of the Tobago Cays in

Appendix III shows the islands and the reef areas. Water taxi operators from all the islands

who make trips to TCMP prefer to enter the Tobago Cays using the southern entrance by

Jamesby Cay; this accounted for more than 47% of all operators (Table 4.7).

Water taxi operators agree that the marine environment is under stress from various threats.

Some provided many possible threats to the environment, whilst the majority gave only one.

The following graphs display the opinions and the possible solutions to some of these

primary threats (Figures 4.3 and 4.4).

The majority thinks that enforcement against speeding and garbage disposal into the sea is

necessary and should be implemented as soon as possible. Others suggested that water taxi

operators be informed about these wrongs and also empower them to help enforce some of

the rules and regulations. Two persons said frequent boat servicing and regular inspection

from officials might reduce impacts on the marine environment from boats

16

50

45

s 40

op

T 35

f

W 30

o 25

t

a

ge 20

15

r

c

en

Pe 10

5

0

po

l

n

s

W

l

a

l

ck

o r

pe

T

uti

e

o

o

o

e

d

p

n

f

sp

i

s

-

eq

o

ng

v

oi

n

l

i

,

u

s

f

s

i

u

ip

e

t

e

m

ar

l,g

e

e

a

n

a

r

t

an

bag

d

e

fish

Figure 4.3: Primary threats to the Tobago Cays Marine Park

25

s 20

op

T

f

W 15

o

ge

ta 10

en

e

rc

5

P

0

inf

e

e

e

e

m

g

o

n

n

n

m

e

r

o

m

fo

fo

fo

p

re

ne

r

r

r

o

w

ce

ce

ce

w

f

ra

a

m

e

re

l

t

p

a

&

e

e

r

rm

q

r

o

f

u

t

i

d

t

n

p

n

e

e

a

e

e

n

n

o

x

a

t

t

c

i

r

u

g

o

b

o

a

g

f

o

m

p

in

a

W

a

e

e

s

rb

t

n

r

a

t

a

to

c

t

t

s

g

h

in

o

p

e

p

e

s

r

s

c

s

ee

p

d

d

k

e

i

i

n

s

s

c

g

po

t

s

io

a

n

l

Figure 4.4: Possible solutions to the threats at the Tobago Cays Marine Park

17

4.2.4 Service(s) offered

Most of the water taxi operators provide more than one service for their customers, with

transporting people between islands and taking passengers on day-long boating trips being

the two most common services (Table 4.8). Some provide only limited services, but most

provide as many as they can, especially during the low season when business is restricted to

only limited number of trips and days for the week. The high and low seasons vary for each

Grenadine Island; Carriacou, Petite Martinique and Mayreau water taxi operators say unlike

other islands, they do not have seasons per se.

Table 4.8: The number of water taxi operators offering different services

Response Boating Transportation

Transportation

Selling

Collecting and

BBQ at

trips

b/w islands

from yachts to

goods

disposing of

night

shore

garbage

Offered 38

40

30

27 12

1

Not offered 9

7

17

20

35

46

4.2.5 Anchoring

The use of anchors by water taxi operators is a potential problem if the anchors are deployed

in dense reef or seagrass areas as this could damage these fragile marine ecosystems. Water

taxi operators must take extra precaution when selecting an area to anchor, as coral reefs and

seagrass beds are particularly susceptible to anchor damage. Most water taxi operators use

anchors to secure their boats at sea (Figure 4.5). A few said they prefer to use moorings if

they are readily available for rental or they use their own moorings. A few others said they

use them interchangeably, that is, they use anchor if they are renting their moorings. More

than half (27 respondents) has both bow and stern lines for more secure tying when docking

and for emergency purposes.

4.2.6 Solid waste

More garbage is being produced in the Grenadines with increasing visitors. Many people are

deeply concerned about improper waste disposal in the Grenadines. They are concerned

about waste disposal from boat operators and visiting tourist yachts. Solid waste (empty oil

bottles, paper, garbage collected from yachts etc.) is often thrown overboard by irresponsible

boat operators or disposed of on a nearby beach. Solid waste is generated on board for about

60% of the water taxi operators. Many provide food and drinks for the passengers on day

trips. The solid wastes vary and include bottles, plastics and aluminium foil. Those that do

provide food and drinks say they take the garbage to a bin or the local dump upon returning

to their island. For Mayreau and Petite Martinique, the waste is taken to Union Island and

Carriacou respectively, which have dumpsites. It is evident that plastics are the most

common of all solid wastes, followed by bottles (Figure 4.6).

18

90

80

70

60

o

p

s

T

W 50

of

40

t

age

30

e

rcen

P

20

10

0

Anchor M ooring

Both

Figure 4.5: Percentage of water taxi operators who use anchors/moorings solely or both

60

50

s

op 40

T

W

of 30

t

a

ge

20

e

r

c

en

P

10

0

bideg

biode rada

gra ble

dable

bottles

styrofoam

plastics

pap

paper er

Figure 4.6: Percentage of water taxi operators who generate a variety of solid wastes

19

4.2.7 Fuel and oil

All the water taxi operators use gas for their engines whether it is a portable tank or a built in

system for direct fuel injection. About 68% of water taxi operators are aware that the tank

should only be filled to ninety percent capacity. Only a few water taxi operators said that

when they are adding the oil to the gas, they fill the tank up to the brim. This particular

question was not applicable to those operators with two-stroke direct fuel injection and four-

stroke engines because these particular engines have a system where the engine does the

mixing of the oil and the gas. One person said they did not know if they filled the tank to the

brim when adding the oil (Figure 4.7).

80

70

60

ops

T 50

W

40

ge of

a

30

c

ent

Per 20

10

0

Yes

No

Don't know

Not applicable

Figure

4.7: Percentage of water taxi operators who fill gas tanks to the brim when adding oil

4.2.8 Engines and engine maintenance

Water taxi operators are very particular with the engine brand they use. The water taxi

operators identify brand with durability and reliability from those that have proven to be

successful for water taxi operators in the past. Yamaha is the leading brand that water taxi

operators across the Grenadines prefer and therefore accounted for 93% (forty-four persons)

from the sample size. Johnson and Evinrude were the other two engine brands used (Table 4.

9).

More than 85% of the water taxi operators in the Grenadines have the conventional two-

stroke engine. Only a few of them have the resources to afford a two-stroke direct fuel

injection engine or a four-stroke engine (Figure 4.8). There may be several reasons for this

fact.

20

Table 4.9: Frequency and percentage of the engine brands water taxi

operators use

Types of engines

Frequency

Percent

Yamaha 44

93

.6

Johnson 2

4.

3

Evinrude 1

2.

1

Total 47

100.0

90

80

70

s

op 60

T

W

50

e

of

tag 40

30

e

rcen

P

20

10

0

conventional 2-stroke

2-stroke direct fuel

4 stroke

injection

Figure 4.8: Percentage of water taxi operators using conventional and direct fuel injection 2-

stroke engine

Many water taxi operators carry out general routine engine maintenance to ensure that the

boat is functioning properly before they depart on their boating trips. A total of 27%

check the gas tank hoses before they go out on each trip, while others check daily, but

surprisingly many rarely check them at all. In addition, 34% of individuals also conduct a

general engine service before each trip and 25% only check the engine when they think it

needs servicing (Table 4.10).

Twenty percent of water taxi operators change a damaged propeller the very next day

after it is damaged (Figure 4.9). About the same percentage said that they could only

change a damaged propeller when they have sufficient money. The majority of more than

50% however, said that they usually wait a few days before changing it.

21

Table 4.10: Frequency and percentage of water taxi operators checking their hoses and

servicing engines at different intervals

Checks hoses for leaks and

Services engine

breaks

Response

Frequency Percentage Frequency Percentage

(%)

(%)

Daily 11

23.4

5

10.6

Weekly 8

17.0

9

19.1

Monthly 0

0

5

10.6

Each trip

13

27.7

16

34.0

As needed

5

10.6

12

25.5

Rarely 8

21.3

0

0

60

50

s

op 40

T

W

30

age of

20

e

r

c

ent

P

10

0

weeks after

as the money the next day days after the no response

the incidents

is acquired

incident

Figure 4.9: Percentage of water taxi operators showing the timeframe in which they can afford

to change a damaged propeller

Although most boat engines have a built-in electric tilt, on some boats it does not

function, but there are also many water taxi operators who do not use the tilt to raise the

engine when in shallow waters even though it may be working. More than 55% of the

water taxi operators said that their engine had an electric tilt. The follow-up question of

whether the tilt was working properly did not apply to those who did not have an engine

with a tilt. Only one person admitted that their tilt was not working properly. All those

without a tilt said they had to manually pull up the engine(s) when in shallow waters or

approaching shallow reef areas. Table 4.11 shows that 12% of the water taxi operators

admitted to not using the tilt or manual pull-up when it was necessary.

22

Table 4.11: Frequency and percentage of water taxi operators who use the

tilt on the engine or manually pull it up

Types of engines

Frequency

Percent

Yes 41

87

.2

No 6

12

.8

Total 47

100.

0

4.2.9 Vessel maintenance

Most water taxi operators in the Grenadines agree that a well-maintained vessel is

necessary for good customer service, aesthetics and releases less pollution to the marine

environment. Maintaining a clean vessel, however, through basic washing/cleaning the

boat (inside and outside) and also through the various processes of scraping, painting,

etc., has high potential of releasing toxins into the marine environment. Many water taxi

operators, 46% clean their boats daily and about 30% clean them weekly (Table 4.12).

Table 4.12: Frequency and percentage of how often water taxi operators

clean their boat

Response

Washing/Cleaning boat

Frequency Percentage

(%)

Daily

22

46.8

Weekly

14

29.8

Monthly

1

2.1

As needed

9

19.1

Rarely

1

2.1

Water taxi operators use these three main agents to clean their boats. About 40 persons

(85%) use a soapy detergent; 24 persons (51%) use bleach and 15 persons use

disinfectant to get rid of `germs' and odours (Figure 4.10).

For most of the Grenadine Islands, water taxi operators find it best to refurbish their boats

during the low season, when they are less busy. Most water taxi operators refurbish their

boats once a year, which accounts for more than 60%. Some prefer to or rather, can

afford to refurbish their boats more than once a year. A few rarely refurbish their boats

(Figure 4.11).

Only nine percent of water taxi operators do not use a special type of paint on the hull of

their boats. These four water taxi operators use house paint and one person chose not to

respond. Figure 4.12 shows 45% of water taxi operators use a type of epoxy paint on the

hull of their boats, while 23% use marine and antifouling paint.

23

45

40

35

r

s

to

30

ra

p

e

x

i

o

25

ta

r

a

te

20

f

w

o

. o

15

N

10

5

0

disinfectant

clorox (bleach)

squeezy (soapy detergent)

Figure 4.10: Number of water taxi operators who use each cleaning agent

70

60

s 50

WTop 40

a

ge of 30

c

ent

Per 20

10

0

2 times/yr

3 times/yr

rarely

yearly

Figure 4.11: Percentage of water taxi operators who refurbish their boats at different intervals

24

50

45

40

s 35

op

T 30

W

25

t

a

g

e

of

20

r

c

en

15

Pe

10

5

0

antifouling

epoxy paint

house paint

marine paint

no response

paint

Figure 4.12: Percentage of water taxi operators who use different types of paint

4.2.10 Education

Nine percent of water taxi operators do not give an information briefing for passengers,

but this is attributed to the fact that they do not provide the service of day trips. Those

who do give a briefing say that they talk about do's and don'ts for the surrounding waters

and about the corals they are familiar with (e.g. fire coral). This was reported as the most

popular topic followed by historical information about the area and about fishing as an

occupation and recreational activity (Figure 4.13).

60

50

o

p

s

40

T

W

of 30

20

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

ge

P

10

0

do's and

history and

currents

not applicable no reponse

don'ts

fishing of area

Figure 4.13: Percentage of water taxi operators who discuss different topics for the educational briefing

25

5 DISCUSSION

As with most research studies, there are several limitations to note and avoid in future

studies of this type. Although this research survey provides many answers and insights,

there were gaps and unresolved issues that were inevitable.

1. The representative sample size of fifty persons was not met due to two refusals

from the water taxi operators and one water taxi operator who did not show up for

the interview.

2. Since the operators live throughout the Grenadines (including Bequia, Canouan,