CERMES Technical Report No 4

An assessment of the vulnerability of the Cocal area,

Manzanilla, Trinidad, to coastal erosion and projected sea

level rise and some implications for land use

DENYSE MAHABIR AND LEONARD NURSE

Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES)

University of the West Indies, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences,

Cave Hill Campus, Barbados

2007

ABSTRACT

An assessment of the vulnerability of the Cocal area, Manzanilla, Trinidad, to coastal

erosion and projected sea level rise and some implications for land use

DENYSE MAHABIR AND LEONARD NURSE

There has been an overwhelming concern over the possibilities of the consequences of the rise in

the production of greenhouse gases, particularly by the developed countries. What poses the

greatest concern is the effect that these gases will have on the climate. The greatest threat

however is going to be faced by Small Island Developing States (SIDS). For all intent and

purposes most small islands can be considered to fall into the category of what some may call the

coast.

This paper looks at and area on the East coast of Trinidad- the Cocal area, its erosion status,

vulnerable resources within that area and the possible impacts that four scenarios of sea level rise

will have on a portion of the East coast in Trinidad. It makes use of Geographic Information

Systems, more specifically the programme Arc View; so as to determine how far inland the sea

will go and what land uses will be affected. In doing so, a holistic approach was taken so as to

formulate ways in which the effects of the rising sea and coastal erosion can be dealt with.

Key words: vulnerability, sea level rise, land use, Trinidad

i

ACKNOLEDGEMENTS

Throughout life we are very fortunate to have met persons who are very helpful, kind,

considerate, understanding and supportive. The time spent on this paper has really brought to life

so many of these persons because the completion of this research paper would not have been

possible without the help of so many people. Firstly I would like to thank the Almighty God

because without him nothing is possible and everything is possible. To my supervisor, Dr.

Leonard Nurse, my heartfelt thanks and gratitude for all the assistance and guidance that you

have given me throughout the duration of the project. I would also like to say special thanks to

the following persons:

Dr. Jacob Opadeyi

Ms Shahiba Ali

Mr. Lloyd Gerald

Dr. St. Clair Barker

Ms. Helen Harris

Mr. Kishan Kumarsingh

Mr. Rodney Thomas

Staff of the Forestry Division of the Ministry

Special thanks to my family and friends (you know who you are) for all of their support and

encouragement, I have truly been blessed.

ii

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT...........................................................................................................................I

ACKNOLEDGEMENTS.........................................................................................................II

1

INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................................................1

2

LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................................................................................2

2.1

CLIMATE CHANGE ....................................................................................................................................................... 2

2.2

THE NATURAL GREENHOUSE EFFECT ........................................................................................................................ 2

2.3

GREENHOUSE EFFECT - A PRECURSOR TO SEA LEVEL RISE ................................................................................... 3

2.4

SEA-LEVEL RISE: PROJECTIONS AND IMPLICATIONS.............................................................................................. 4

2.4.1

The global perspective.........................................................................................................................................4

2.4.2

Possible impacts of sea level rise.......................................................................................................................4

2.5

THE REGIONAL PERSPECT IVE..................................................................................................................................... 6

2.6

THE LOCAL PERSPECTIVE ........................................................................................................................................... 7

2.6.1

Existing environment............................................................................................................................................8

2.6.2

Geology of Trinidad..............................................................................................................................................8

2.6.3

The climate of Trinidad........................................................................................................................................9

2.6.4

El Niņo Southern Oscillation ............................................................................................................................10

2.6.5

Flooding................................................................................................................................................................10

3

METHODOLOGY AND DATA SOURCES .............................................................................................................11

3.1

USE OF GIS ................................................................................................................................................................ 12

3.2

STEPS INVOLVED IN USING GIS............................................................................................................................... 12

4

THE S TUDY AREA .........................................................................................................................................................17

4.1

COCOS BAY MANZANILLA-MAYARO................................................................................................................. 19

4.1.1

Geographical circumstances.............................................................................................................................19

4.1.2

Coastal land use..................................................................................................................................................20

4.1.3

Seismic conditions off Trinidad's east coast..................................................................................................20

4.1.4

Coastal form and features .................................................................................................................................20

4.1.5

Bathymetry............................................................................................................................................................20

4.2

OCEANOGRAPHIC FEATURES................................................................................................................................... 21

4.2.1

Currents and circulation....................................................................................................................................21

4.2.2

Waves and tides...................................................................................................................................................21

4.3

VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT ................................................................................................................................ 21

4.4

RESOURCES THAT MAY BE AT RISK IN THE STUDY AREA..................................................................................... 22

4.4.1

The Nariva swamp ..............................................................................................................................................22

4.4.2

Mangrove communities......................................................................................................................................23

4.4.3

Manzanilla beach................................................................................................................................................24

4.4.4

The Manzanilla Mayaro Road ..........................................................................................................................29

4.4.5

The community.....................................................................................................................................................30

5

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION.....................................................................................................................................32

5.1

RESULTS..................................................................................................................................................................... 32

5.2

DISCUSSION................................................................................................................................................................ 33

6

MEASURES THAT CAN BE ADOPTED TO COUNTERACT COASTAL EROSION AND THE

PROJECTED IMPACTS OF RISING LEVEL..................................................................................................................35

6.1

PERFORMANCE OF PAST COASTAL STRUCTURES................................................................................................... 36

6.2

RECOMMENDATIONS................................................................................................................................................. 37

6.2.1

Protective mechanisms that may be utilized...................................................................................................37

6.2.2

Plans for the development of the study area...................................................................................................38

7

CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................................................................................40

8

REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................................................................42

iii

Citation: Mahabir, D. and L. Nurse. 2007. An assessment of the vulnerability of the Cocal area,

Manzanilla, Trinidad, to coastal erosion and projected sea level rise and some implications for

land use. CERMES Technical Report No.4. 44 pp.

iv

1 INTRODUCTION

"Is Trinidad Sinking" was the caption used for a programme aired on one of the local television

stations in Trinidad and Tobago approximately four years ago. An alarming caption I thought at

the time, but then I pondered a little and realized that indeed I must agree not based on the

information given in the programme however, but on my own knowledge.

According to the host of the programme - Dr. Bhawan Singh, a climatologist and the principal

investigator of an Earthwatch Institute field project in Trinidad, he states and I quote, "Based on

the limited data set that we have for Trinidad, it's showing that sea level is rising at about 8-

10mm per year, which is way above the global average, which is only 2mm per year." I

stopped and pondered a bit more, thinking that such a statement needed to be backed up by more

evidence, which clearly the man stated was lacking. It must be said though that to the 'naked

eye' I have always wondered, since I have travelled along the East coast often, 'how long will it

take for the sea to reach the road and when is someone going to do something about it?'

It has been widely documented that the developed countries are responsible for the increases in

the level of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other green house gases in the atmosphere that have led to

a change in the overall climatic conditions. While these larger countries are the main

contributors to this change, it is the smaller islands that will suffer the greatest consequences,

since they will be impacted upon the most. Small islands are widely considered to be vulnerable

to sea level rise. Among the factors which exacerbate their vulnerability are their low resource

bases, over reliance on a few sectors within the economy such as tourism or agriculture, a high

population density and a tendency for that population to be concentrated in low-lying coastal

locations, which will be impacted upon by the rise in sea level. Increasing human pressures, lack

of resources, and the limited size of the islands also limit adaptation options. The Caribbean, of

which Trinidad is a part, is one such region in terms of population that could be affected by

storm surges which will be amplified given a one-meter rise in sea level.

Up until quite recently this phenomenon of sea level rise has gone almost unnoticed by many

planners and institutions holding the portfolios that cover environmental awareness and

management. At this present time there is a lot of literature available on the forecasted rise in

sea level and also on the impacts and implications of such a rise. Information on the Caribbean

Islands is limited, but the impacts on these islands would not really vary from what those other

small islands in other parts of the world would have to face. The impacts that such islands would

face include coastal flooding, erosion, saltwater intrusion, damage to coastal infrastructure, all of

which would eventually lead to the displacement of many coastal communities.

In the Caribbean, the project - Caribbean Planning and Adaptation to Global Climate Change

(CPACC) has now been initiated, and all participating countries have set up units to facilitate

project implementation at the national level. In Trinidad and Tobago work is being done in

collaboration with the Environmental Management Authority.

In order to truly consider the impacts that sea level rise will have on Trinidad, it is important to

look at it from a holistic point of view. Aspects such as climate, geology, the location of the

island, all of these need to be considered just to name a few.

For the purposes of this research paper, an area of Trinidad was selected since it was noted that

this coastal segment is already under threat from erosion, in addition to which the area possesses

many features which are of great importance including a Ramsar site the Nariva Swamp, and a

main transportation link on the East coast.

1

This area is exposed to the high wave energy of the Atlantic Ocean and many coastal protection

mechanisms have been put into place, none of which has been successful thus far. One of the

objectives of this paper is to determine whether the erosion activity is due primarily to wave and

current action, sediment deficiencies, sea level rise, or a combination of these.

Chapter two of this paper deals with the issue of sea level rise and climate change at the local,

regional and global levels, as well as the possible impacts that such a change may have on the

island. It also gives a general overview of the island of Trinidad, its climate, its geographic

location and other features of the island. The following chapter takes a look at the study area in

more detail and focuses on an area on the Eastern part of Trinidad. The objective of this part of

the paper is to look at various features of the study area, as well as the potentially vulnerable

resources of the area. Chapter four is the one that allows for quantitative analysis to be carried

out, its objectives being to identify the coastal resources that would be affected by different

scenarios of sea level rise and to quantify the area and the value of the resource that will be

affected. All this will be done using the Geographic Information System programme - Arc

View.

Based on the findings of chapter four and the previous chapters, recommendations will be made

with regards to protective and mitigative mechanisms that could be used to conserve the area, as

we know it.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Climate change

Previous studies at the international and regional level have proven that natural and human-

induced climate variations ranging from short term i.e., seasonal to interannual variability due to

El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) to long-term changes (i.e., temperature shifts and sea-

level-rise associated with greenhouse warming) may have significant impacts. These include

impacts on water resources, on grasslands and livestock, on agriculture and forests, on the

physical, biological and chemical aspects of the coastal zone, and even on human health. The

associated occurrence of extreme events like floods, droughts, and severe weather conditions, as

well as steady change of average climatic conditions and morphological variations of the

coastline are present ly a matter of serious concern,

(http://www.gcrio.org/CSP/IR/Iruruguay/html).

Human activities e.g. (fossil fuel burning and land use changes) are increasing the atmospheric

concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHG's), which in turn are altering the radioactive balances

and warming the atmosphere. Aerosols on the other hand tend to scatter out incoming radiation

resulting in a cooling effect on the atmosphere. Unfortunately, the net effect remains as a

warming due to the much shorter life spans of aerosols as against the much more long-lived

GHG's, (http://www.ema.co.tt/Fnc/V_a.htm).

2.2 The natural greenhouse effect

Energy emitted from the sun (solar radiation) is concentrated in a region of short wavelengths

including visible light. Much of the short wave solar radiation travels down through the earth's

atmosphere to the surface virtually unimpeded. Some of the solar radiation is reflected straight

back into space by clouds and by the earth's surface. Much of the solar radiation is absorbed at

the earth's surface, causing the surface and the lower parts of the atmosphere to warm (Figure

2.1).

The warmed earth emits radiation upwards, just as a hot stove or bar heater radiates energy. In

the absence of any atmosphere, the upward radiation from the earth would balance the incoming

2

energy absorbed from the Sun at a mean surface temperature of around -18°C, 33° colder than

the observed mean surface temperature of the earth,

(www.katipo.niwa.cri.n2/ClimateFuture/Greenhouse.htm). The presence of greenhouse gases in

the atmosphere accounts for the temperature difference. Heat radiation (infra-red) emitted by the

earth is concentrated at long wavelengths and is strongly absorbed by greenhouse gases in the

atmosphere, such as water vapour, carbon dioxide and methane. Absorption of heat causes the

atmosphere to warm and emit its own infra-red radiation. The earth's surface and lower

atmosphere warm until they reach a temperature where the infra-red radiation emitted back into

space, plus that directly reflected solar radiation, balance the absorbed energy coming in from the

sun. As a result, the surface temperature of the globe is around 15°C on average, 33 °C warmer

than it would be if there were no atmosphere. This is called the natural greenhouse effect,

(www.katipo.niwa.cri.n2/ClimateFuture/Greenhouse.htm).

2.3 Greenhouse Effect - a

precursor to sea level rise

At the turn of the century, scientific

opinion regarding the practical

implications of the greenhouse

effect was sharply divided. Since

the 1860's, people have known that

by absorbing outgoing infrared

radiation, atmospheric CO2 keeps

the earth warmer than it would

otherwise be. Throughout the first

half of the 20th century, scientists

generally recognised the

significance of the greenhouse

effect, but most thought that

humanity was unlikely to

substantially alter its impact on

climate. The oceans contain 50

times as much CO2 as the

atmosphere, and the physical laws

governing the relationship between

Figure 2.1 A simplified diagram illustrating the greenhouse

the concentrations of CO2 in the

effect (based on a figure in the 1990 IPCC Science Assessment)

oceans and in the atmosphere

seemed to suggest that this ratio

would remain fixed, implying that only 2 percent of the CO2 released by human activities would

remain in the atmosphere, (http://users.erols.com/jtitus/Holding/NRJ.html).

In the last decade, climatologists have reached a consensus that a doubling of CO2 would warm

the earth by 1.5- 4.5oC, which would leave our planet warmer than it has ever been during the

last two million years. Moreover, humanity is increasing the concentrations of the other gases

whose combined green house effect could be as great as that due to CO2 alone, including

methane, chlorofluorocarbons, nitrous oxides and sulphur dioxide. Even with the recent

agreement to curtail the use of CFCs, global temperatures could rise as much as 5oC in the next

century. Global warming would alter precipitation patterns, change the frequency of droughts

and severe storms, and raise the level of the oceans,

http://users.erols.com/jtitus/Holding/NRJ.html).

3

2.4 Sea-level rise: Projections and implications

As a result of global warming, the penetration of heat into the ocean leads to the thermal

expansion of the water and this effect, coupled with the melting of glaciers and ice sheets, results

in a rise in sea level. Sea-level rise will not be uniform globally but will vary with factors such as

currents, winds, and tides--as well as with different rates of warming, the efficiency of ocean

circulation, and regional and local atmospheric effects. The current best estimates for sea-level

rise is approximately 5 mm/yr, with a range of uncertainty of 2-9 mm /yr. This rate is between

two to four times higher than the rate experienced in the past 100 years (i.e., 1.02.5 mm/yr).

Model runs also show that sea level would continue to rise beyond the year 2100 (because of

lags in the climate response), even with assumed stabilization of global GHG emissions (Wigley,

1995, quoted in IPCC 1996, WG II, Section 9.3.1.1).

2.4.1 The global perspective

The level of the oceans has always fluctuated with changes in global temperatures. During the

last major ice age when global temperatures were 5ēC lower than today, much of the ocean's

water was tied up in glaciers and sea level was often over one hundred meters lower than today.

Global sea level trends have generally been estimated by combining, averaging and evaluating

the trends at tidal stations around the world. These records suggest that during the last century,

worldwide sea level has risen 10 to 25cm, much of which has been attributed to the global

warming of the last century, (http://users.erols.com/jtitus/Holding/NRJ.html).

When considering shorter periods of time, worldwide sea level rise must be distinguished from

relative sea-level-rise. Although global warming would alter worldwide sea level, the rate of sea

level rise relative to a particular coast has more practical importance. Relative sea level rise

varies for more than one meter per century in some areas with high rates of groundwater or

mineral extraction, to a drop in extreme northern latitudes,

(http://www.epa.gov/globalwarming/publications/impacts/sealevel/landuse.html).

The projected global warming could raise worldwide sea level by expanding ocean water,

melting mountain glaciers, and causing the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica to melt or

slide into the oceans. Climate change could also influence local sea level causing a change in the

intensity and direction of winds, atmospheric pressure and ocean currents.

All assessments of future sea level rise have emphasised that much of the data required for

accurate estimates is unavailable. As a result, studies of the possible impacts generally have

used a range of scenarios, as is the case in this paper.

2.4.2 Possible impacts of sea level rise

Coastal flooding

This is the most obvious impact of sea level rise. It refers both to the conversion of dry land to

wetland and the conversion of wetlands to open water. Unlike most dry land, all coastal

wetlands can keep pace with a slow rate of sea level rise. Coastal wetlands are sensitive to sea

level rise as their location is intimately linked to sea level. However they are not passive

elements of the landscape and, as sea level rises, so the surface of any coastal wetland rises due

to sediment and organic matter output. If this keeps pace with sea level, the coastal wetland will

grow upwards, but if it does not, the wetland steadily sinks relative to sea level. Intertidal areas

will be steadily submerged. Vegetated wetland systems will be submerged during a tidal cycle

for progressively longer periods and may die due to waterlogging, causing a change to bare

intertidal areas, or even open water. Therefore coastal wetlands show a dynamic and non-linear

4

response to sea-level-rise. Coastal wetlands with a small tidal range are more vulnerable than

those with a large tidal range.

Direct losses of coastal wetland due to sea-level-rise can be offset by inland wetland migration

(upland conversion to wetland as sea level rises). In areas without low-lying coastal land, or in

areas that are protected by `hard' engineering structures to stop coastal flooding, wetland

migration cannot occur, (http://www.ima-cpacc.gov.tt/climate_change_facts.htm).

Erosion

In many areas the total shoreline retreat from a one-meter rise would be much greater than

suggested by the amount of the land below the one-meter contour on the map, because shores

will also erode. While acknowledging that erosion is caused by many other factors, Brunn

(1962) showed that as sea level rises, the upper part of the beach is eroded and deposited

offshore in a fashion that restores the shape of the beach profile with respect to the sea level.

The "Brunn Rule" implies that a one-meter rise would generally cause shores to erode 50 to 200

meters along sandy beaches, even if the visible portion of the beach is fairly steep.

Saltwater intrusion

Sea level rise would generally result in saltwater intrusion into aquifers and estuaries. In

estuaries, the gradual flow of freshwater towards the oceans is the only factor preventing the

estuary from having the same salinity as the ocean.

The impact of sea level rise on ground water salinity could make some areas uninhabitable even

before they are actually inundated, particularly those that rely on unconfined aquifers just above

sea level. Generally these aquifers have a freshwater "lens" floating on top of the heavier salt

water, a phenomenon known as the Ghyben-Herzberg relationship (Figure 2.2).

On low, small islands that are largely composed of coral or other porous materials, salt water

intrusion into the underlying interior is quite common. The drilling or digging of wells on these

islands and especially on along the shoreline must be done with care. Going too deeply will

penetrate the transition zone and result in salt-water infiltration and the contamination of the

fresh water in the well.

Figure 2.2 Saltwater interface in an aquifer according to Ghyben-Herzberg relationship

(Source: http://www.ecy.wa.gov/pubs/0111013)

5

2.5 The regional perspective

The 1995 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Second Assessment Report

estimated changes in the number of people who would be affected by flooding from storm surges

due to a one-meter sea level rise and the associated losses in coastal wetlands. The rise in sea

level assumed was just above the top end of the range for 2100 suggested by IPCC, and the

calculations did not consider the rapid socio-economic changes, which are occurring in the

coastal zone, (http://www.ima-cpacc.gov.tt/climate_change_facts.htm).

In the Caribbean region, more than 60% of the population live in coastal areas (Nurse, pers.com).

This is as a result of many factors, one main one being that most of these islands are heavily

dependent on tourism as the main contributor to their economy, and many developments have

taken place along the coastal areas so as to boost the tourism industry. Traditionally many of the

coastal communities were heavily dependent on the fishing industry as a main income earner

with fish being a major protein source in their diets. Concentration along the coast therefore

made access to the resource easier and transportation cost less, which is still the case today.

Establishment of communities close to the coast was easier in that land in these areas was

generally flat and as you go further inland the terrain becomes more hilly in most cases. In the

case of Trinidad, settlement along the East coast was driven as a result of the increasing

discoveries of oil fields off that coast, an industry on which many families financially depend.

Awareness of climate change and its potential implications for the region's socio-economic

development is fairly recent. Research on anthropogenically induced climate change and its

impacts are only at the fledging stage in the Caribbean. Consequently, the scenarios and

projections on which impacts for the Caribbean are made are based largely on global and

hemispheric findings because these are more readily available. In addition, the level of public

education and awareness about the potential impacts of climate change is low. As such there is

really no data available on the effect that climate change has had on the sea level, although some

changes have been observed in coastal areas.

The IPCC has indicated that the need to implement strategies to cope with sea-level-rise is more

urgent than previously thought. Present stress on coastal resources could be further impacted by

projected increases in sea level as a direct consequence of global warming. The Caribbean's

vulnerability to sea level rise is likely to be reflected in adverse effects on its freshwater supply,

coastal erosion rates, the frequency and intensity of tropical storms.

At the forefront of dealing with the issues of climate change and sea level rise in the region is the

Caribbean Planning for Adaptation to Global Climate Cha nge (CPACC) Project. CPACC has its

origin in the Global Conference On the Sustainable Development Of Small Island Developing

States, which took place in Barbados in May 1994. During this conference, the Small Island

Developing States (SIDS) of the Caribbean requested the Organisation of American States

(OAS) assistance in developing a project on adaptation to climate change for submission to the

Global Environmental Facility (GEF). The project was submitted for consideration of the GEF

and endorsed by the Caribbean Community Market (CARICOM) Ministers of Foreign Affairs.

The project was approved by the GEF Council and CPACC became effective in April 1997 with

twelve countries participating. These were Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize,

Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the

Grenadines and Trinidad and Tobago (CPACC, 1999).

The Regional Project Implementation Unit (RPIU) was established at the Cave Hill campus in

Barbados, while the administrative body, the Center for Environment and Development of the

University of the West Indies (UWICED) is based at the Mona campus in Jamaica, to ensure

6

effective coordination and management of project activities at the regional level. All

participating countries have established National Implementation Coordinating Units (NICU)

composed of a network of existing institutions, to facilitate and coordinate project

implementation at the national level (CPACC, 1999).

The overall objective of CPACC is to support Caribbean countries in preparing to cope with the

adverse effects of global climate change, particularly sea level rise, in coastal and marine areas

through vulnerability assessment, adaptation planning, and capacity building linked to adaptation

planning. Specifically, the project will:

ˇ Strengthen the regional capability for monitoring and analysing climate and sea level

dynamics and trends, seeking to determine the immediate and potential impacts of Global

Climate Change (GCC).

ˇ Identify areas particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change and sea

level rise.

ˇ Develop an integrated management and integrated framework for cost effective response

and adaptation to the impacts of GCC on coastal and marine areas.

ˇ Enhance regional and national capabilities for preparing for the advent of GCC through

institutional strengthening and human resource development.

ˇ Identify and assess policy options and instruments that may help initiate the

implementation of a long-term program of adaptation to GCC in vulnerable areas.

(Source: CPACC, 1999).

2.6 The local perspective

As mentioned earlier Trinidad and Tobago is one of the countries participating in the CPACC

project, the first phase of which has now come to an end. A Working Group has been set up to

determine the implications of global warming, climate change and sea level rise for National

development. This group has been Cabinet appointed in Trinidad and Tobago in 1990 and has

multi-sectoral representation (equivalent to National Climate Committees in most countries).

The working group is currently chaired by the Environmental Management Authority.This

Working Group has the mandate to advise Government on climate change related impacts.

The Working Group assumed the role of the National Implementation Coordinating Unit (NICU)

to oversee the implementation of CPACC in Trinidad and Tobago and also overseeing the

preparation of Trinidad and Tobago's Initial National Communication under the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

As part of the Working Group's work four ad hoc committees, inter alia, have been set up. The

first is a Sub-committee on Public Awareness whose function is to develop Public

Awareness/Education Strategies for the period 2000-2002. This sub-committee has put forward

recommendations that have already been implemented e.g. printing of posters and exercise books

containing information on climate change. The second is a Sub-committee on Climate Data

whose function is to collect, collate and analyse historical climate-related data e.g. rainfall,

temperature, coastal erosion, saline intrusion etc, with a view to detecting climate variability and

the possible impacts of climate change. The third is a Sub-committee on Health Vulnerability so

as to analyse the incidences of vector borne diseases, agricultural pests incidences and the

incidence of respiratory diseases such as asthma, the data being collected and analysed by the

Climate data sub-committee. The fourth Sub-committee is on the Clean Development

7

Mechanisms (CDM) under the Kyoto Protocol (which calls for countries to reduce the level of

greenhouse gases emitted in the atmosphere by a certain time) in order to determine Trinidad and

Tobago's opportunities under the CDM.

The Climate Data group has liased with the National Wetlands Committee in conducting an

economic valuation of the Nariva Swamp (a Ramsar site), using the experience gained from the

CPACC pilot project "Economic Valuation of Coastal and Marine Resources' which was done in

Trinidad and Tobago.

To date there is no hard data to analyse sea levels, the main reason for the unavailability of sea

level rise data thus far is because the Global Circulation Model that is being used to predict sea

level rise has not been resolved to the scale of small islands, in addition to which there is a lack

of a long time series of measured tide gauge data. However, data collected from three

monitoring stations established under the CPACC Component 1 can be used in the long term to

establish sea level fluctuations.

Only one estimate of sea level rise for Trinidad has been documented and that was done by Dr.

Bhawan Singh. According to Dr. Singh, Trinidad's sea is rising at about 8-10 mm/yr, which he

states is clearly above global average. There is some question as to the scientific basis of the

information presented by Dr. Singh, since it seems that no direct measurements were done on sea

level rise. What Dr. Singh presented was data on rainfall, temperature, coastal erosion and tidal

data, but no data on sea level rise. The programme aired on television therefore presented

information based on the results of field studies conducted over a ten year period on the variables

mentioned above.

2.6.1 Existing environment

The islands of Trinidad and Tobago lie roughly between 10 deg.N and 11.5 deg.N latitude and

between 60 deg.W and 62 deg.W longitude or 14 kilometers (at its closest point) off the eastern

coast of Venezuela. These are the two most southerly islands in the eastern Caribbean

archipelago. As a result of their southerly location, Trinidad and Tobago experiences two

relatively distinct seasonal climatic types which will be discussed in greater detail in section

2.4.3.

2.6.2 Geology of Trinidad

A geological outline of Trinidad indicates that the island is generally an uplifted mudflat that was

formed in the estuary of South American Rivers, millions of years ago. The soils of south

Trinidad are generally weak clays, with some weak Guaracara limestone. As the northern range

was uplifted from the greater depth by tectonic activity, the soils of the northern part are more

consolidated. The dominant soils of the northern range are schist clays that are quite hard but

can disintegrate when wet, (Ministry of Works, 2000).

The compressibility of the deeper soils that support the coastal terrain is of particular interest. If

the shoreline is underlain by compressible soils (such as peat), then the gradual compression and

consolidation of these deeper layers may be a factor that contributes to the geological settlement

of the coastal land, and alternatively the rise of the sea level relative to the shore. The level of

coastal land may also be affected by the production of oil and/or gas, particularly in the vicinity

of the large gas and oil exploration fields offshore.

8

2.6.3 The climate of Trinidad

The island experiences a typical tropical climate with the main seasonal variation of rainfall

occurring between the wet (June to December) and dry (January to May); with minimal

precipitation during the dry. The main climatic determinants affecting Trinidad and Tobago are:

ˇ The latitudinal position and strength of the subtropical ridge of High pressure (the Azores

Bermuda High) - a semi permanent hemispheric feature.

ˇ The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) the major rainfall/cloud producing system

that is heavily responsible for our rainy season.

ˇ The Mid- Atlantic Trough of low pressure an upper tropospheric feature that assumes

increased prominence mainly during the fall and early winter months.

ˇ Daytime convection, Orography and Land size.

Controls of a lesser degree are: -

ˇ The occasional intrusion of polar fronts into our latitudes, mainly during the dry season

as shear lines, bringing with them some rainfall.

ˇ Tropical waves and cloud clusters in the easterly wind current. This feature is noticeable

only during the hurricane season from June to November.

ˇ Tropical cyclones i.e. Depressions, Tropical storms and Hurricanes. (Even though these

systems cause severe damage and bring phenomenal rainfall, they cannot be given major

status owing to their low frequency of occurrence).

ˇ The Sea-Breeze effect. It is noteworthy that the sea breeze has a rather telling effect on

west coast rainfall during the summer (wet season) months in that it is responsible for

occasional heavy showers and sometimes thundershowers in and around the city of Port

of Spain. During these events, the prevailing easterlies are weak and onshore westerlies

on the west coast may dominate, especially after a hot day to drive a front of conversion

inland, (http://www.ima-cpacc.gov.tt/climate_change_facts.htm).

Rainfall

The movement of the Azores-Bermuda High pressure zone is responsible in large measure for

the two seasons. The northward movement of the High and its seasonal weakening during the

summer months significantly lessen its rainfall suppressive effects on Trinidad and Tobago. The

ITCZ migrates northward and affects the area. Trade winds weaken and give way to a moister

equatorial flow from the east or east- southeast and the climatic regime changes to a more

equatorial type.

The first and major peak in rainfall is around June or July and is associated with the northward

movement of the ITCZ. The other peak occurs in November and can be attributed to an unstable

transitional air mass before the true northeasterly trade winds reassert themselves as the ITCZ

migrates again southward. November is also a month marked with upper tropospheric trough

activity, (http://www.ema.co.tt/Fnc/Climate_of_Trinidad.htm).

Although small, total annual rainfall for Trinidad, varies from over 3048mm in the North East

(NE) to approximately 1524mm in the North West (NW) and South West (SW) peninsulas of the

island, with the difference between seasons very marked. In the wet season it is 2032mm and in

the dry it is 1016mm (Berridge, 1981).

9

Temperature

Overall for Trinidad and Tobago there are only small seasonal variations in temperature and no

significant spatial variation. The average annual temperature in Trinidad is 25.7oC.

Temperatures for the most part average between 24.5oC in January and 26.7oC in

May,(http://www.ema.co.tt/Fnc/Climate_of_Trinidad.htm).

Winds

The prevailing wind system is the Northeast Trades. Winds are easterly with either a weak

northerly component during the dry season or an even weaker southerly component during the

wet season. The directional persistence is high (>95%) with speeds averaging 11 to 30 km h-1

during the day. Gusts of over 65km h-1 are rare and usually associated with heavy showers and

thunderstorms. At nights wind speeds generally fall below 7km h-1 inland and, at areas close to

sea level, it is generally calm.

The sea breeze has a greater influence on the eastern side of Trinidad than on the western due to

the direction of the prevailing winds. Its influence is in the form of increased cloudiness and

showers and can be felt some 35km inland on most days. The western half of the island is not so

favored as the sea breeze is weaker, only serving to reduce the strength of the easterlies in that

area. Sea breeze induced showers are not noticeable on Trinidad's western half.

2.6.4 El Niņo Southern Oscillation

El Nino describes the warm phase of a naturally occurring sea surface temperature oscillation in

the tropical Pacific Ocean. Southern Oscillation refers to a shift in surface air pressure at

Darwin, Australia and the South Pacific island of Tahiti. When the pressure is high at Darwin, it

is low at Tahiti and vice versa. El Nino and its sister event La Nina- are the extreme phases of

the southern oscillation, (www.ogp.noaa.gov.enso/). La Nina is characterized by unusually cold

ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific, the opposite of El Nino. Typically, El Nino occurs

more frequently than La Nina, that is, La Nina events occur after some (but not all) El Ninos,

(www.pmel.noaa.gov/tao/elnino/la-nina-story.html).

The Caribbean including Trinidad and Tobago has experienced significant El Nino

teleconnections. It is now well established that during El Nino years, Tropical cyclone activity

in the Caribbean is markedly suppressed. In its place however, is an augmentation of rainfall

especially in wet season months. This effect is not always evident and is dependent on the

severity of the El Nino episode.

Interestingly, during intense El Ninos, a teleconnected area of drought that is manifested in

Northeastern Brazil, shows expansion and tends to migrate into the Guyanas and Eastern

Venezuela. It is in such situations that the area of deficit rainfall may affect the southern

Caribbean and thus Trinidad and Tobago. This was particularly evident during the El Nino of

1997/1998 during which Trinidad and Tobago experienced drought-like conditions from late

August 1997 to May 1998, interrupted only by a wet November 1997,

(http://www.ema.co.tt/Fnc/climate_of_Trinidad.htm).

2.6.5 Flooding

This is a perennial problem in Trinidad where heavy rains can cause flooding in major river

basins. The Caroni river basin is the most notable, with river basin flooding occurring at least

once per year, during the period October to December,

(http://www.ema.co.tt/Fnc/Climate_of_Trinidad.htm).

10

In some cases flooding has led to the death of some people and one event that stands out

occurred in May of 1993, when freak thundershowers triggered heavy flooding and mudslides,

which eventually led to the death of five persons and a total of ten persons being injured. In

1996 floods affected a total of two hundred persons in that year. Over the period 1990-2001, one

thousand, four hundred and ten persons were affected in the sense that houses were totally

flooded, furniture and appliances were damaged, as well as some houses were washed away.

Flooding has also led to a very heavy sediment load being carried to the coast, this ultimately

means that the visibility through the water would decrease and less sunlight would be able to

penetrate. Sunlight is an important element in marine food chains, since the primary food

source, that is, plankton rely on energy from the sun to carry out photosynthesis. This means that

there will be a shift in the food chain, as species further up the chain will respond to the decrease

in production of plankton. There are coral reefs located off the East coast in closer vicinity to

Tobago and these will also be affected by heavy sediment loads in the water and will be

smothered by it.

3 METHODOLOGY AND DATA SOURCES

The data used and reproduced in this paper was obtained from various sources. It must be noted

that only limited data was available on Trinidad with respect to sea level rise. The bulk of data

presented in the paper was obtained from the IMA, that is either directly or indirectly as is the

case with the information obtained from the Drainage Division, which was bought from the

IMA. Information from the IMA included data on beach profiles set up along the East coast,

which provided data on whether there was erosion or accretion at various sites along the coast.

An aerial photograph, again obtained from the IMA was used to verify the phenomenon of

erosion and accretion at said sites. Other information obtained from the IMA that was

particularly useful was a Land Use Map. The map was used to verify land use types in the study

area when field visits were conducted in the presence of forestry officers that are responsible for

patrolling and the everyday protection of the area. Changes that were observed during the field

visits were corrected in the legend of the map when the data on the map was being processed for

use in the GIS programme Arc View.

The EMA also provided information on the present strategies that are being put in place to deal

with sea level rise and climate change. Information was obtained from the Land and Survey

Board of Trinidad and Tobago, that is, what is presented in Appendix 1. Appendix 1 has

calculations that show the elevations of land in the study area. Nails have been imbedded at

different points along the Manzanilla- Mayaro Road, the locations are given in the appendix. A

level was used, the starting point for measurements being a set of benchmarks set up by the

government. For each station the closest benchmark was used. The elevation of the land at the

different stations was calculated in relation to mean sea level. The calculations were done by

simply subtracting the sum of the foresight measurements from the sum of the backsight

measurements (S Backsight S Foresight). A negative value meant that the elevation was

below mean sea level, while a positive value meant that the elevation was above mean sea level.

The Internet also proved to be a very important source particularly in conducting the literature

review and obtaining information about the Nariva Swamp. NEDECO Consultants provided

useful information on what was required to combat climate change and sea level rise, namely in

a report that they had prepared for the Drainage Division on Coastal Protection Works in

Trinidad and Tobago.

11

3.1 Use of GIS

GIS accommodates the compilation into a common database of a wide range of data needs that is

typical of multi-disciplinary initiatives e.g. coastal management. GIS facilitates data sharing,

standardization and co-ordination, thereby avoiding duplication in data collection efforts. With

GIS you can carry out evaluation of alternative planning scenarios and spatial identification of

conflicting or competing interests. Overall GIS allows for a `dynamic decision-making process'.

GIS has many weaknesses, but these lie mainly in the limitations of its use. It must be noted that

the resources required in terms of cost and time are great and is a limiting factor in the

implementation of GIS for decision-making. Lack of data in terms of accessibility and quality

also limits its use. In the case of this study the accuracy and resolution of the maps used will

also be an issue.

It must be noted that environmental data collected from historical sources and satellite imagery is

not as accurate as the data obtained from ground truthing. However, it can provide an excellent

first overview that would allow planners to make decisions that would maximize the protection

of the environment for marine, amphibious, air, and land operations. This method can easily be

transferred to any part of the world. Using this approach, one can quickly create an accurate GIS

system that can serve as a useful planning tool.

3.2 Steps involved in using GIS

Using a land use map, digitizing was done and the following layers were generated:

ˇ Contours

ˇ Land Use

Using the GIS software Arc View, the layer with contours was prepared so as to obtain the

Contour theme ensuring that heights were in metres, there was closure to the zero contour, and

also to include roads in the creation of the TIN model. The Land Use Theme was generated

containing only natural resources e.g. beaches, swamps. The Land Use Theme was generated

containing only coastal resources that result from human intervention or direct investment e.g.

agriculture.

A TIN model was created of Contour 25. The TIN model was used to generate new contours

with a contour interval of 0.5m. The following pairs of contour lines were selected:

-heights equal to 0.0m and 0.5m

-heights equal to 0.5m and1.0m

-heights equal to 1.0m and 1.5m

-heights equal to 1.5m and 2.0m

Polygons were created from the following pairs of polylines:

-polyline 0.0m and 0.5m

-polyline 0.5m and 1.0m

-polyline 1.0m and 1.5m

-polyline 1.5m and 2.0m

An INTERSECT overlay was done with the coastal resource theme:

Land use

12

On each of the following polygons

- polygon 0.0m and 0.5m

- polygon 0.5m and 1.0m

- polygon 1.0m and 1.5m

- polygon 1.5m and 2.0m

Figure 3 summarises the process.

13

Build

Create contours

Select and convert to shapefile

Input

Contours 0

TIN

0.5m

Contours >0

and 25ft

contour

and 2m

intervals

Study area

Contours in

(poly)

study area

Overlay

Build polygons

Clean: Intersect and Pseudonodes

Closed

Polygons 0 to

Snapped

contours in

Merge

2.0

polylines

study area

Intersect

Study area

(line)

Land use

Vulnerable land use

Figure 3.1 Cartographic model

14

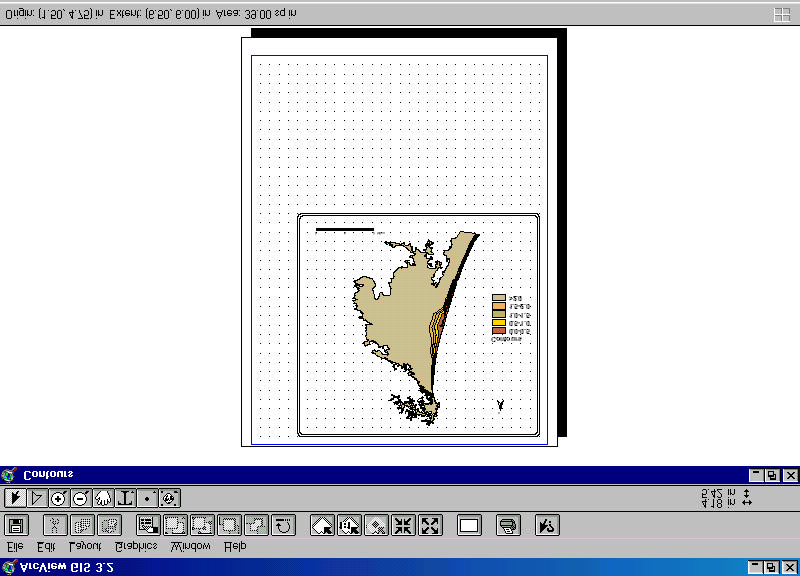

Figure 3.2 below is a representation of the land use theme. It shows the different types of land

uses in the study area. Eight different types of land uses were picked up in the study area.

These were as follows:

ˇ Swamp

ˇ Forest

ˇ Bush Bush Wildlife Sanctuary

ˇ Grassland

ˇ Biche Bois Neuf Area

ˇ Agriculture

ˇ Extended Squatting

ˇ Coconut Plantation

Land Use Types

Agriculture

Biche Bois Neuf Area

Bush Bush Wildlife

Sanctuary

Coconut Plantation

Extended Squatting

Forest

Grassland

Figure 3.2 Different types of land uses

The different colours indicate the different polygons. Each polygon represents an interval of sea

level rise, for example, a sea level rise between 0.0 - 0.5 m.

15

Contours

0.0-0.5

0.5-1.0

1.0-1.5

1.5-2.0

>2.0

Figure 3.3 The different contour lines created to represent the different scenarios of sea level rise

16

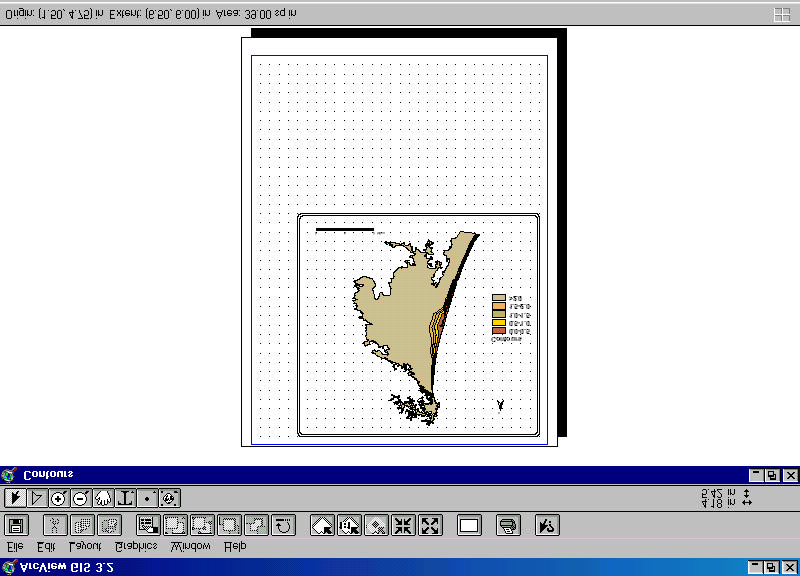

The contour theme and the land use theme were intersected, so that areas common to both

themes would have been selected (Figure 3.4).

Agriculture

Biche Bois Neuf Area

Bush BushWildlife

Sanctuary

Coconut Plantation

Extended Squatting

Forest

Grassland

Figure 3.4 The intersection of the two layers

4 THE STUDY AREA

The boundaries demarcating the study area are as follows:

- the coastline on the east,

- the boundary of the Nariva swamp to the west,

- Manzanilla Point to the north,

- Radix Point to the south.

17

Figure 4.1 Location of the study area

The East Coast of Trinidad, formerly known as Bande de L'est is noted for its special charm and

historical background (TIDCO, 1999). The area encompasses a host of coconut plantations, with

one Copra factory still in operation. The village of Kernaham is located in the study area, with

agriculture being the mainstay of the residents. Agricultural production includes aquaculture, the

growing of rice, watermelon and vegetables. In other areas there is also livestock production

taking place along the coast.

Running parallel to the coast is the Manzanilla Mayaro Road, which connects the town of

Mayaro to the town of Sangre Grande. On the opposite side of the road lies the biggest wetland

area in Trinidad-the Nariva Swamp. The swamp stretches over 6000 hectares and includes

mainly palm swamp forest, an endemic species of Moriche palm (Mauritia flexuosa var

trinitensis) and 1550 hectares of highland forests. Presently kayaking tours are being conducted

in the swamp by the Caribbean Discovery Tours Limited, (www.users.carib-

link.net/~wildfowl/article.htm).

18

4.1 Cocos Bay Manzanilla-Mayaro

4.1.1 Geographical circumstances

The country's location is in the close vicinity of a large continent, with two narrow straits of

approximately 10 15 km. At these points, tidal currents build up higher velocities, with local

effects on coastal erosion and coastal stability.

Open exposure to the Atlantic Ocean makes important stretches of the coast the target to strong

waves. Significant erosion often results, causing much damage to property, expensive and

strategic infrastructure (coastal roads, bridges, resorts), dislocation of economic activities, loss of

economic interest (tourism and business), valuable historical assets and ecological values. In

addition to which, this zone may be directly exposed to hurricane tails as well, (Ministry of

Works, 2000).

Coastal hydrology

Along the East Coast, coastal water movement occurs predominantly under the influence of the

energy impact of ocean waves that approach the coast from the northeast, east and southeast, in

accordance with the predominant wind directions.

The major rivers that have outlets under tidal influence in the area of Cocos Bay, that contribute

significant amounts of material to the coastal budget, and therefore influence the coastline

evolution and morphology are:

ˇ Nariva River

The Nariva River enters the sea at some 12km south of Manzanilla Point (Figure 4.2). It

represents the channel connection of the Nariva Swamp with the sea. According to field

evidence and resident information, the tidal prism through this tidal channel does not reach the

swamp area. In fact the tidal currents around the inlet are known to be quite weak (Ministry of

Works, 2000). Also, due to the

buffer-like role of the swamp, only

small sand volumes are spilled into

the sea, thus the morphological

effects are most likely limited to the

immediate surroundings of the

channel's inlet. The sand spit built

up on the left side of the inlet seems

to present perennial stable features.

The present river inlet- as

consolidated by man-made works,

made within the last 2-3yrs seems to

be a quite stable one (Ministry of

Works, 2000).

Figure 4.2 The mouth of Nariva river meets the sea

ˇ Ortoire River

It outflows into the ocean at the southern limit of the Cocos Bay, just north of Radix Point.

Based on work done by the Ministry of Works, Drainage Division, it is most likely that the

sediment volumes brought by the river into the sea are quite significant. The presence of the

Radix Point peninsula in close southern proximity to the inlet creates a solid boundary, which

funnels in/out the tidal volumes with increased velocities. It should also be considered that the

same Radix Point creates a natural protecting `breakwater' of the river mouth. The sediment

19

load of the river contributes to the build-up of the sand spit, which is a perennial feature of the

river inlet's left bank.

ˇ L'Ebranche River

This represents the northern limit of the Manzanilla beach and is located just south of Manzanilla

Point. Although tidal currents are weak here, flood tidal current would most likely register

increased velocities, due to the guiding effect of the Manzanilla promontory. Due to the river's

low gradient over its coastal stretch and its apparent quite vegetated watershed, sediment load to

be brought into the sea is likely to be very small, but just enough to maintain a modest sand spit

at its mouth. Occasionally with high water levels (during storms and heavy rainfall) in its basin,

it can break the sand bar that separates the riverbed from the seacoast.

4.1.2 Coastal land use

The Manzanilla Beach at Cocos Bay extends between Manzanilla Point in the north and Point

Radix in the south. The beach forms a natural barrier between the Nariva swamp and the

Atlantic Ocean. This barrier also forms the base of the Manzanilla Mayaro Road, a

transportation link of great national importance.

A number of resort buildings have been built on this barrier strip. The land is under the

cultivation of coconuts and is also used for the grazing of Buffalypso. Over the last 10 years

erosion of the coast has been a continuous source of concern to the owners of resort homes and

agricultural estates, community dwellers and persons who use the road on a regular basis (taxi-

drivers, market vendors, etc.).

4.1.3 Seismic conditions off Trinidad's east coast

Seismic conditions are monitored by the Seismic Research Unit of the University of the West

Indies. The nearest fault system to the study area is associated with the Manzanilla Bank, which

extends east of Radix Point. According to Speed, 1985, the present deformation front of the

active (South American) foreland thrust and fold belt in Trinidad appears to be just south of the

island and hence, the study area. According to Ambeh and Russo (1993), after a moderate

earthquake on the east coast in March 1988, which resulted in only minor damage, activity in this

area subsequently continued, but on a reduced scale.

Increased seismic activity suggests that waves and tides will be amplified. This coupled with the

rates of erosion in certain areas (Sectio n 4.4.3), means that saltwater will be propelled even

further inland. Ultimately the effects are twofold, increased volume of seawater inland and

increased erosion as more water moves inland.

4.1.4 Coastal form and features

East Trinidad shows significant coastal zone variation, characterised mainly by three stretches of

low coast, separated by prominent headlands at Manzanilla and Radix Points (Ministry of

Works, 2000). In the study area, there is a popular resort and in the central stretch, the Cocal

barrier beach. The latter is the pivotal physical feature responsible for the freshwater

impoundment, which maintains the Nariva Swamp.

The beach has remained stable in many areas, whereas there has been erosion and accretion in

other areas. This will be discus sed in greater detail in Section 4.4.3.

4.1.5 Bathymetry

The seabed of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) off Trinidad's east coast shows significant

variation in type and topography. On the east, it dips gently from the coast towards the edge of

20

the continental shelf approximately 100km away. The main prominent sea-floor feature in the

southern portion of the east coast is the Manzanilla Bank. This extensive shallow feature

comprises a hard- bottom bank, which runs in an east-northeast direction from Radix Point to

Darien Bank, which emerges as a small reef formation approximately 30km due east of

Manzanilla Point (Ministry of Works, 2000).

4.2 Oceanographic features

4.2.1 Currents and circulation

Off Trinidad's east coast, the dominant direction of current flow is towards the north. Sea water

supply to Trinidad's marine environment comes mainly from the Guiana Current (Kenny and

Bacon, 1981). On approaching Trinidad, the Guiana current divides into two streams. The outer

stream passes northward along the Atlantic east ocean and has been reported as having average

speeds of up to 2 knots (EMA, 1997).

The northward current circulation patterns are affected by seabed topography and coastal

geometry. These include the eddying effects close to the shoreline of semi-enclosed bays,

between prominent headlands. The circulation pattern is also influenced by seasonal variations

in atmospheric conditions and water quantity inputs. These may result in spatial and temporal

fluctuations in the dominant current flow patterns.

4.2.2 Waves and tides

Trinidad's marine environment is characterised by wind driven waves originating predominantly

from the east. Open water swell is generally approximately 2 metres, but higher waves are at

times generated by tropical or extreme winter storms (Ministry of Works, 2000).

Generally the tidal regime is semi-

diurnal, characterised by two periods

of high and low tides each day. Tidal

range varies with moon phase, sun

position and the time of the year. On

Trinidad's east coast it is on average

1.3m (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Rough waves - typical of the East coast

4.3 Vulnerability assessment

Vulnerability to Climate Change is defined as the extent to which a natural or social system is

susceptible to sustaining damage from climate changes. Vulnerability in this context therefore is

related to the sensitivity of the system to a change in climate, i.e. the degree to which a system

will respond to a given change in climate including both beneficial and ha rmful effects and its

ability to adapt to the changes in climate. Adaptation of necessity must focus on the degree to

which adjustments in practices, processes or structures can moderate or offset the potential for

damage, or take advantage of the opportunities created due to a given change in climate,

(http://www.ema.co.tt/Fnc/V_a.htm).

21

The ecology of small islands generally is characterized by a limited range of terrestrial and

coastal ecosystems, surrounded by a vast expanse of ocean. The vegetation usually consists of

groups of easily dispersed species, which have a tendency to be restricted in their distribution.

Forests (including stands of mangroves), coral reefs, and sea grass communities provide a range

of food, other resources and ecological services. Biodiversity is highly variable and depends on a

combination of physical and other factors (e.g., location, area, geology).

The ecological systems of small islands--and the functions they perform--are sensitive to the

rate and the magnitude of changes in climate. These systems provide food, medicine, and energy;

process and store carbon and other nutrients; assimilate wastes; purify water and regulate runoff;

and provide opportunities for recreation and tourism (IPCC 1996, WG II, Section 9.2).

The economies of small island states are sensitive to external market forces over which they have

little control. The economies generally are dominated by agriculture, fisheries, tourism and

international transport activities (air and sea). In the case of Trinidad and Tobago a significant

petrochemical and petroleum industry has developed and has become the country's leading

revenue earner.

Some low-lying small island states--such as the atoll nations of the Pacific and Indian Oceans--

are among the most vulnerable to climate change, seasonal-to-interannual climate variability, and

sea-level rise. Much of their critical infrastructure and many socioeconomic activities tend to be

located along the coastline, in many cases at or close to present sea level (Nurse, 1992; Pernetta,

1992; Hay and Kaluwin, 1993). Island systems would be extremely vulnerable to any changes in

the frequency or intensity of extreme events (e.g., droughts, floods, hurricanes, and storm

surges). Indeed, vulnerability to these and other natural hazards--including some that may not be

influenced by climate change (e.g., tsunamis, volcanoes)--contributes to the cumulative

vulnerability of many small island states (Maul, 1996).

The IPCC Second Assessment Report has quoted vulnerability indices for different categories of

countries as derived by Briguglio (1993). The index is calculated as the average of three

variables: export dependence, insularity and remoteness and proneness to natural disasters. The

highest vulnerability is indicated by the values closest to zero. The vulnerability index for Small

Island Developing States (SIDS) carries the highest value at 0.590. This suggests that small

island states are the most vulnerable to climate change impacts.

4.4 Resources that may be at risk in the study area

4.4.1 The Nariva swamp

In 1992, Trinidad and Tobago designated Nariva Swamp for the list of Wetlands of International

Importance maintained under the Ramsar Convention. Nariva has the most varied vegetation of

all wetlands in Trinidad and Tobago. The swamp stretches over 6,000 hectares and includes

mainly palm forest, an endemic species of Moriche palm and over 1,550 hectares of highland

forest. The ecology of this swamp is unique, serving as the spawning ground of many freshwater

fish including the Cascadura (Hoplosternum littorale), an important source of food for many

people, (www.users.carib-link.net/~wildfowl/article.htm). It is especially important for large

numbers of waterfowl and the main site still sustaining populations of anaconda (Eunectes

murinus) and manatee (Tricheus manatus) and it supports considerable populations of molluscs

and crustaceans. It comprises state lands, including the Bush Bush Wildlife Sanctuary, part of

the Ortoire Nariva Windbelt Reserve and the proposed Nariva National Park. The Nariva

Swamp qualifies under several of the Convention's criteria for identifying internationally

important sites.

22

Nariva swamp was considered a prime site for a national park and tourism centre in 1980, since

it easily meets all the requirements of a national park in Trinidad and Tobago. The conservation

policy at the time was to protect in perpetuity, areas in the country that are significant examples

of the natural heritage, unique ecosystems and habitat types and to promote understanding,

appreciation and enjoyment of this heritage in ways which will not degrade the resource,

(www.geocities.....ainforest/Canopy/8466/Nariva4.html).

The Nariva Swamp is presently being used for tourism activities, particularly Eco-tourism; the

area being one that is rich in a wide range of flora and fauna. Management of this area therefore

has important implications for the tourism industry in Trinidad since tourism has been identified

as a sector for economic growth in the Trinidad and Tobago Tourism Master Plan (1995).

Wetland reserves have considerable potential for generating income from tourism and recreation.

However, care must be taken to ensure that any infrastructural development does not reduce the

value of the area for tourism or compromise its ability to perform its ecological functions.

4.4.2 Mangrove communities

The capacity of mangrove forests to cope with sea-level rise is greater where the rate of

sedimentation approximates or exceeds the rate of local sea-level rise. Indeed, Hendry and

Digerfeldt (1989) have shown that mangrove communities in western Jamaica were able to keep

pace with mid-Holocene sea-level rise (ca. 3.8 mm/yr). However, the adaptive capacity of

mangroves and other coastal wetlands to sea-level-rise (usually by landward migration) is now

severely limited in many localities by increasing human activities such as land reclamation for

physical development and the construction of coastal protection works. It has been suggested, for

instance, that a 1-m rise in sea level in Cuba will drastically affect the viability of 333,000 ha of

these wetland communities (approximately 93% of Cuba's mangroves) (Perez et al., 1996).

Additionally, adaptive capacity will vary among species; some species of mangroves appear to

be more robust and resilient than others to the effects of climate change and sea-level rise

(Ellison and Stoddart, 1991; Aksornkaoe and Paphavasit, 1993 as cited in IPCC (1996)).

Some ecologists believe that mangrove communities are more likely to survive the effects of sea-

level rise in macrotidal, sediment-rich environments--such as northern Australia, where strong

tidal currents redistribute sediment (Semeniuk, 1994; Woodroffe, 1995 as cited in IPCC

(1996))--than in microtidal, sediment-starved environments like those in many small islands

(e.g., in the Caribbean) (Parkinson et al., 1994 as cited in IPCC (1996)). Most small islands fall

within the latter classification; therefore, they are expected to suffer reductions in the

geographical distribution of mangroves. Furthermore, where the rate of shoreline recession

increases, mangrove stands are expected to become compressed and suffer reductions in species

diversity in the face of rising sea levels.

On the other hand, Snedaker ((1993) as cited in IPCC (1996)) argues that mangroves in the

Caribbean are more likely to be affected by changes in precipitation than by higher temperatures

and rising sea levels because they require large amounts of fresh water to reach full growth

potential. He hypothesizes that a decrease in rainfall in the Caribbean would reduce mangroves'

productive potential and increase their exposure to full-strength seawater. Thus, peat substrates

would subside as a result of anaerobic decomposition by sulphate-reducing micro organisms,

leading to the elimination of mangroves in affected areas, Snedaker ((1993) as cited in IPCC

(1996)).

23

4.4.3 Manzanilla beach

In many areas there has been erosion of the beach, while in others the beach has remained stable.

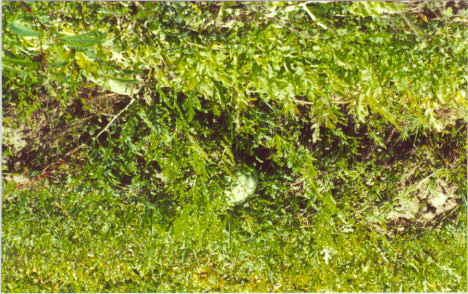

Erosion has led to the destruction of many coconut palm trees (Figure 4.4). The beach has

become a popular destination for the after Carnival Ash Wednesday "lime", when thousands of

tired revellers congregate to enjoy the last of the festivities. The Manzanilla beach therefore, is

of significant social and cultural importance. A 1 m rise in sea level would increase the threat of

erosion and possibly lead to further coastal land loss.

Figure 4.4 Erosion has caused the toppling of many coconut trees

Data regarding erosion in this area were obtained from a NEDECO report that was prepared for

the Ministry of Works, Drainage Division, the raw data being obtained from the IMA. The IMA

has five monitoring stations set up along the beach. The approximate locations of such stations

are as follows:

Figure 4.5 Location of IMA stations

IMA station

Location vs. Nariva inlet

Location vs. Ortoire inlet

Data were presented for

1

13.2 km N

-

the years 1990-1999.

2

1.5 km N

-

Figure 4.5 represents

3

2.3 km S

4.9 km N

sand volumes at the

4

3.9 km S

3.2 km S

northern part of the

5

6.7 km S

0.6 km S

beach, that is, the part

north of the Nariva inlet. The figure shows that this part of the beach has remained fairly stable

with some accreting tendencies. The NEDECO report indicates that by using aerial photo

comparisons this tendency was confirmed. It was found that the average accretion rate at 1.7km

north of the Nariva inlet was 0.17 m/yr (Figure 4.5). This area coincides with the approximate

location of IMA station 2. Various sand volume parameters such as total sand volume, upper

beach sand volume and total net differential volume followed over the profile confirmed this

average net dominant accreting feature.

The southern part of the beach is monitored by stations 3, 4 and 5. The visual evidence that the

area has experienced significant coastal erosion (e.g. undermined road and exposed tree roots) is

supported by actual measured field data which is presented graphically in Figures 4.6 and 4.7.

The graphs indicate that while there were a few periods of accretion, the principle trend has been

that of erosion. Overall, the average erosion rate for the period was approximately 0.55m/yr.

24

Evidence of upper beach erosion was also presented (Figures 4.9, 4.10 and 4.11). Figure 4.9

would suggest that erosion was virtually zero for the period 1992-1994, however, the rate

increased as time went by. Figure 4.11 is a representation of the same period 1992-1999 and

indicates the total sand volume for each of the two-year periods. In most cases the volumes

indicated that there was more erosion (indicated by the ne gative values) than accretion (indicated

by the positive values).

Aerial photographs provided by the IMA, suggests that the most intense erosion occurs 3 km

north of the Ortoire river mouth. Figure 4.14 indicates that in some areas of this stretch of the

beach, the road is behind the shore at distances as short as 5m. Station 5 is located along this

stretch of beach. Data collected by the IMA and processed by NEDECO indicates that there was

rapid erosion (approximately 1.7m/yr) during the period 1996-1999 (Figure 4.12).

50

40

30

20

10

0

-10

January

July

October

-20

-30

Sand Volume (m3/m) -40

-50

Control Months

Profile 1